Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Éditions Écrits Noirs

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

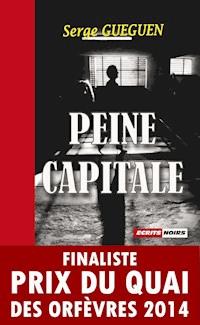

Forbidden flights during which mercenary paratroopers are airdropped over central France with their payloads of cocaine… But also the “forbidden flights” of several of the finely-drawn characters seeking vainly to flee their troubled pasts…. Against a backdrop of French popular culture, Serge Guéguen weaves a compelling tale of criminal intent, implacable vengeance and ultimate comeuppance, in an action-packed intrigue which throughout blends realistic narrative with telling psychological insights.A perfect combination of action and mind games for a gripping thriller.EXCERPTIt was the grey, dreary month of November. The prison of Villepinte, in the northern outskirts of Paris, seemed even more sombre and depressing than usual. Laid out in the middle of the fields like a set of Lego blocks, the place was soulless and life-less, despite the yellow bands which the administration had painted on the high barbed-wire-topped walls.In the waterlogged car-park, a bus was waiting for its "clients": depending on the time of day, these might be either inmates or visitors. The driver, a Black, probably of mixed race judging by the light-ness of his skin, was absorbed in reading his sports daily. Reflexively, he reached out to turn up the volume of the “Tropiques FM” radio station, as the fast and furious Caribbean Zouk music invaded the cabin without disturbing anyone, since the seats behind him were still empty. Just like every day at that time.ABOUT THE AUTHORAfter spending a fulfilling career within a French company and writing plays and scripts, Serge Guéguen decided to focus on what he is most passionate about: crime novels.Today, four of his books have been published and one of them has been awarded the Quai des Orfèvres prize in 2014.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 333

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Any resemblance to actual events or persons, either living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Écrits noirswww.ecritsnoirs.com

By the same author (original French editions):

- M.R. 13/18

- Peine capitale

- Violeurs d’anges

- Terminus mortel

Chapter 1

It was the grey, dreary month of November. The prison of Villepinte, in the northern outskirts of Paris, seemed even more sombre and depressing than usual. Laid out in the middle of the fields like a set of Lego blocks, the place was soulless and lifeless, despite the yellow bands which the administration had painted on the high barbed-wire-topped walls.

In the waterlogged car-park, a bus was waiting for its "clients": depending on the time of day, these might be either inmates or visitors. The driver, a Black, probably of mixed race judging by the lightness of his skin, was absorbed in reading his sports daily. Reflexively, he reached out to turn up the volume of the “Tropiques FM” radio station, as the fast and furious Caribbean Zouk music invaded the cabin without disturbing anyone, since the seats behind him were still empty. Just like every day at that time.

At regular intervals, he glanced mournfully at the exit door of the concrete cube which was used for receiving the families of the inmates. The minutes ticked slowly by, the red dial on the dashboard flashing on and off like the tick, tock, tick, tock of an old grandfather clock... In this Godforsaken place, it was waiting which defined everything. It was even the only thing that existed, whether you were on the inside or the outside. It is what prison time is made of, a space in which minutes last not sixty seconds but much longer. How much longer? Its duration is beyond the imagination of the average citizen and difficult for its inhabitants to define. The only constant was patience. To get to the shower, the visits, the activities... The Moroccan writer Ahmed Sefrioui wrote: " Waiting is what existence is all about." In prison, waiting only ensures survival, nothing more.

So the bus driver did like everyone else connected with the prison world, he waited: for the passengers, for the starting signal, for the light to turn green at the car-park exit....

The police siren preceded the arrival of the police van itself. The policeman drove up to the entrance. The heavy double doors opened and sucked in the vehicle with its barred windows. What had this guy done to be here, how old he is, is he a repeat offender? Such were the questions that any anonymous onlooker might have asked themselves watching the place, where the main occupation was just whiling away the time.

At the end of the morning, a dejected, distraught woman emerged from the concrete cube and got onto the bus without a single look for the man sitting behind the wheel, and went to settle down near a window. While she waited for the bus to set off for the Paris suburban railway station, she scanned the walls behind which a son, a husband or a brother was paying his debt to society before regaining his freedom.

In this little oasis of happiness, lock number 25421, known as Dio, whose real name was Sergio Nardi, switched off his TV.

‘What a great bloody idea! Why on earth didn’t I think of it earlier?’

He pulled a half-empty packet of menthol cigarettes from his pocket. He took one and tapped it on his finger to pack the tobacco more tightly. Then the Zippo lighter in his left hand performed magic as the lid snapped open against his jeans, the thumbwheel rubbed against the fabric and the flame instantly sprang to life. He had done the trick thousands, maybe millions, of times, ever since he had seen an American soldier on leave in Marseilles light his cigarette that way.

Dio stretched out on the bed and started thinking. His left hand gently massaged his neck as he sent curls of smoke up towards the ceiling. The position was symptomatic of his state of concentration. Already as a teenager lying on a park-bench in the Place Caffo, in the Belle-de-Mai area of Marseilles, he had acquired this habit, which invariably prompted the jeers of his friends. And as usual, he remained silent: he was elsewhere, in another galaxy. No-one had ever managed to break in on his thoughts in these times of intense brain activity. The intensity of his concentration disconnected him from reality to a point where it could put him in danger by making him vulnerable.

And in fact, when his pals discovered this behavioral flaw of his, they would often use it as an excuse for having a good laugh. Like pushing him off the bench he was lounging on in the fine spring sunshine, before quickly scattering into the nearby streets. Some towards the Rue de la Belle-de-Mai and its leg-breaking slope, the others towards the Boulevard de la Révolution or the Rue Ricard. Dio’s fits of anger were fearful to behold and greatly feared. They were all aware that it was best not to fall into the hands of this strapping lad of one-metre-eighty and ninety kilos, otherwise...

The Nardis had lived in Marseilles for several generations, after the family arrived in the working-class district of Belle-de-Mai in the early twentieth century. The grandfather, originally from Tuscany, began working at the Saint-Charles sugar refinery before it burnt down a few years after he was hired. Having thus lost his job, he got taken on at the SEITA tobacco factory where he worked until he retired. His father followed in his footsteps and it was obvious that Dio would also work in the cigarette factory. But a different destiny awaited him. After normal schooling at the Bernard Cadenat school, a vestige of the Popular Front of 1936, he signed up for a car mechanic apprenticeship. His curiosity and seriousness quickly ensured him a sound reputation as an expert mechanic.

Things could well have stopped there if a chance encounter had not led him off along different, rather murkier paths: those of crime. It was another son of an immigrant family, a Belgian, who had also grown up in the Belle-de-Mai district, who heard of his mechanical talents and suggested he should take part in armed robberies with him, as the driver. Francis the Belgian was a few years Dio’s senior and in this way set him on a path which many families feared: too many former neighbourhood youngsters were rotting away in the local Baumettes prison because the money to be got from drugs, whores or robberies was easier to come by than the pittance they could earn at the factory.

In 1974, when Dio came back from his military service, battle was raging in the Belle-de-Mai districy; a few months earlier, a number of Francis’s men had been murdered by rival bullets. There followed the Tanagra massacre, which ended in four more deaths, including that of a man who had conned the Belgian. From this gang war, Dio emerged unscathed. That did not last very long though, and at twenty-four, the prison sentences started to rain down: for forgery and the use of forged documents in '78, for violation of the arms laws in '81, for counterfeit money, and so on.

After learning the trade with the veterans of the "French Connection", Dio decided to give up drugs and set up on his own. He started researching famous break-ins, to work out how different gangs operated and thus acquire additional expertise in what was to become his specialty: logistics.

But to fully understand the mechanics of a case, he asked one of his contacts to put him in touch with a particular member of the “Lyons gang”, a '70s crime legend who had succeeded in robbing the General Post-Office in Strasbourg. The team was looked up to as being true masters in the organisation of robberies, having walked off with the equivalent of € 7,120,000 in just a few minutes without a drop of blood being shed.

Following his "appeal for witnesses", he was "summoned" to Lyons to meet a member of the team who was still alive: Chaïn. After a few random movements around the town just to lose any possible policemen, Dio was to go to an old bistro in the suburbs of Lyons where Chaïn was expecting him.

The taxi-driver had hesitated to take him into the heart of this ill-reputed industrial estate. The seedy bar was located on the corner of two streets, one of them providing a view of oil refinery vats and the other overlooking a scrap yard. The low sky shed a gloomy light over the scene.

When Dio pushed the bistro door open, it creaked from lack of oil; the inside was lit by greenish neon strip-lighting. Some curtains which looked more grey than white hung over the glass frontage which itself was opaque rather than transparent. The cleaning scraper had long lain unused in the broom cupboard. Two men at the counter were intent on their dice-game, busy playing for money. In the corner opposite the door, a man of around forty was calmly studying form in his copy of Paris Turf.

Dio walked over to the bar on his right, behind which a barman who distinctly lacked style, a Gauloise drooping from the corner of his mouth, was nonchalantly drying a slightly chipped glass of dubious cleanliness. His blotchy red complexion gave away his penchant for lifting the elbow, as confirmed by his half-full glass, hidden discreetly beside the till. On the walls, faded advertisements projected the same dismal image as the paint peeling from the ceiling.

Dio walked up to the counter.

‘A coffee, please.’

The barman set his smoldering cigarette down in the ashtray and turned to start up the espresso machine. While the coffee dribbled slowly out, he placed a saucer with a spoon on the counter and pushed towards it the shiny metal sugar-bowl. Mechanically, he took the cup and placed it in the centre of the saucer.

‘There you are.’

‘Thanks.’

The bartender picked up his cigarette and resumed drying. Dio lifted the scalding beverage to his mouth. A grimace twisted his lips, and he put the cup down and added two extra lumps of sugar to neutralise the bitterness of the black liquid. The minutes ticked slowly by on the dial of the clock, a free gift from a famous brand of Pastis. Dio showed no sign of impatience, he knew he was being watched, but by who? The bartender, the players, the man with the newspaper? What was for sure, though, was that at the slightest suspicion, he really wouldn’t be feeling that comfortable on this foreign turf, and there was nothing his size would be able to do for him.

At one minute to three, the bartender turned on the radio, just as the end of a song gave way to the news. Heads lifted when it came to the items of general news: the journalist was describing an attack on a bank in Paris. Dio felt mounting tension as the journalist made his comments. Dio had often experienced this in Marseilles, in the bar where he was a regular; whenever an attack took place, ears pricked up imperceptibly to listen out for the names of any friends who might have had the bad luck of falling on the "battlefield". But this time the robbers had escaped and nobody yet knew who they were, except that there were four of them. Then came the racing results and the barman turned off the radio. End of the "musical" interlude. Ten past three: he’d been waiting for nearly three quarters of an hour. At a quarter past three, he heard a voice from behind him:

‘With that accent of yours, you’ve got to be from Marseilles, right?’

Dio turned around abruptly, not having heard the man coming: it was the one with the newspaper. He looked into the cold eyes of a man who was being hunted by all the police forces in France. The very one who was to tell him the story of the break-in at the General Post-Office in Strasbourg.

‘Sure, I’m Dio, I’m a friend of the Belgian’s.’

‘I know. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t be here and neither would you. Come on, let's sit down.’

After shaking hands energetically, the two men settled at the table the racing paper was lying on, set slightly apart from the others.

‘What’ll you have?’

‘A coffee, please.’

‘Georges, bring us a coffee and a beer please!’

‘So, it seems you want to know certain details the fuzz would love to know about too, to be able to send us down. So what’s the deal?

They looked each other in the eyes.

‘It’s because I want to retrain.’

‘Retrain? Come on, out with it!’

‘Well, as you know, I started out in armed robbery, I got caught and like everyone else I don’t want to go back in clink!’

‘Yeah, just like the rest of us. Carry on!’

‘So, my idea is to become a logistics expert as it were, like there are experts for explosives.’

Dio fell silent while the barman set down the drinks.

‘Go on, you’ve aroused my curiosity!’

‘So the idea would be for me to hire out my skills to prepare a job, you know, casing the joint, then organising everything, the cars, the guns, and so on’.

‘That sounds pretty smart. And how do you take your share?’

‘Firstly, I’m not on the job myself. Once I’ve finished preparing the game plan, I submit it to a team that then pays me an amount to be agreed on and if the job works out OK, I take a 10% cut of the proceeds!’

Chaïn scratched his chin, looking out of the window. A man entered the bistro.

‘Hi there everyone! A beer please, Georges!’

Sitting at the table, Dio suddenly felt ill-at-ease; a deafening silence fell. Chaïn remained a while without speaking. Dio knew he mustn’t rush things: without him, there would be no project left. The man’s experience was pure gold and would be a stepping-stone for his future. Because it was always better to start out from a successful robbery than from a lousy plan. This obvious truth, when forgotten, had led certain crooks at best to gaol, and at worst to the cemetery.

The gangster looked at him coldly, before a grudging smile played at the corner of his lips; Dio felt all his muscles suddenly relax.

‘Okay, I'll give you the general outline. But no real details, to avoid any trouble and loose talk, in case you ever get caught, right?’

‘Right!’

‘You know that if you ever betrayed us by blabbing, you won’t stay around for very long!’

Dio felt the threat was very real – the guy sitting opposite him was certainly no joker, but for now what he was interested in was the straight narrative.

‘The first thing you should know is that we did a life-size rehearsal of the real job with the post office in Chambery, in December 1970. We were a commando of five, dressed in blue overalls. We held up the security guards and grabbed the cash. For the getaway, we used a van, then a waiting backup car, and to finish with, we just got on a train.

‘How much did you get?’

‘2.2 million francs; not bad, eh?’

‘Not bad at all!’

‘That was the first step.’

‘Was it so important?’

‘It certainly was, because that way we sussed out the flaws in the system!’

‘Meaning?’

‘I’ll leave that one for you to work out, kid!’

‘Okay.’

‘Before attacking the General Post-Office in Strasbourg, we worked for a year and a half on reconnaissance: the movements of the security guards, the number of bags, the fallback routes, the routines of the postal workers, and so forth.

‘It takes quite a bit of dough to do all that, though?’

‘It sure does, mate! It’s like being on the run, if you haven’t got something stashed away, you're dead.’

‘How much did it cost you?’

Chaïn smiled. Dio understood that he would only be told what was deemed necessary.

‘Then came the inside of the post office; we dressed up as postmen to be able to draw up an accurate plan of the premises. We’d spotted a locked door at the back of the building. So, a few days before the job, we showed up in overalls and to justify our presence with the director, we said we’d come to check the locks.

‘And he believed you?’ asked Dio.

Chaïn burst out laughing. ‘Why shouldn’t he have believed us? Don’t we look like workmen?’

‘That’s not what I meant, but wasn’t that a tad naïve of him?

‘A tad stupid of him, you mean! Anyway, we made the most of it and changed the lock on that door. Then on June 30th, 1971, at 9 am, we went into action. We went in through the door we’d got the keys to, wearing grey overalls, and then we waited.

‘And nobody asked you anything?’

‘No. We were hiding behind the door! Then the piggy-bank of the Banque de France arrived. The cops escorting it couldn’t go inside, so they stayed put.

‘Why was that?

‘Because at that time, they weren’t allowed to go inside. Then the security guards headed for the vault. And we came up on them, and Bob’s your uncle!’

‘Were you armed?’

‘Yeah, we had machine guns. But the main thing was that we started talking with a Marseilles accent!’

‘What?’

‘What do you think? The idea was to put the cops on the wrong track. Then the security guards, completely surprised, handed over the bags. We backtracked and took off in the van.’

‘And that was all?’

‘No, before we left, we slid a piece of paper into the lock, just to try to hold up any pursuers. And that was it – we’d pulled off the biggest robbery in history: nearly 11 million francs.’

‘And you went back to Lyons?’

‘Yes, but not as the crow flies. We used several backup cars, driving into Germany then down through the Vosges region, on a real sight-seeing tour! And here I am.’

‘Well fuck me, it sounds so simple on paper!’

‘Sure, the principle’s dead simple, but you have to work everything out in advance!’

‘So I see!’

Chaïn looked him full in the face.

‘That’s why your idea’s so brilliant, because there are loads of guys who are ready to do the job itself, but the number of guys in the business who can actually use their brains is very small.

‘Thanks!’

‘That's all I can tell you, kid, now I’ve got to go.’

They stood up and shook hands.

‘We’ve never met, okay?’

‘I lost my way coming to this place.’

‘No problem, just walk three hundred metres down the street and you’ll see a bus stop that’ll take you to the station. See yer!’

Chaïn turned on his heel and walked out. Dio was never to see him again: he learned some time after their meeting that he had been found dead, slumped over the wheel of his car with two large-calibre projectiles in his head.

From the day of this meeting, Dio set out to work for some of the most seasoned crooks in the business and he was not to set foot in any of the state's prisons before quite some time...

Chapter 2

Dio got up to put the kettle on. He spooned a dose of "Nescaf" into his glass and added a lump of sugar. For several days now he had been alone in the cell, his last companion having just been released after eighteen months inside for possessing coke. The kettle whistled shrilly and he filled his glass with scalding water. The soluble coffee granules danced a jig before dissolving, rather like a newly-arrived first-timer. At first he "hits out" at every wall of the administration: the warders, the searches, the doors, the corridors…, every part of the daily routine. Then gradually, as time goes by, he dissolves into the formless mass of the other prisoners slouching around slowly and bleakly and, just like the coffee granules, joins the apparently homogeneous, multicolored mass. This bunch of individuals only manages to survive by dint of swapping, dealing, and thieving in a world where the rule is the absence of trust. Prison is a world filled with tension, forever fretted by pettiness, thrilling to some and nerve-wracking to others. The warder who "forgets" to inform an inmate of an activity he could go to, or cigarettes that are ordered late, meaning a fortnight with no tobacco. These petty daily acts of retaliation keep the atmosphere poisonous, sometimes taking an inmate straight to the cooler, on top of adding to his stretch. Throughout the history of prison-life, it has always been the screws who win out in the end, as the word to the wise would have it...

After drinking his coffee in small sips, Dio had a wash at the sink. A shower every day is for the clinks of the future, perhaps in 2100. For now it was just three times a week and after doing sport. Dio took especial care over shaving today, because he was being “extracted" to go and give an account of himself before the judges at the criminal court of Bobigny. For it had been almost a year now since he had been initially remanded in custody: since then, the system – the magistrates, the police and the prison authorities – had taken malicious pleasure in letting the proceedings drag out. All because he’d been nicked for a stupid bloody mistake of his which had been the only thing the cops had been able to nail him for! After they’d been chasing him for over twenty years!

This time they had been relentless in trying to pin as much as they possibly could on him. They had combed through his bank accounts and obtained warrants to search every possible place, including his family’s homes. But in vain: they did not find a thing, because there was not a thing to find. So, by default, he was going up before an ordinary criminal court, whereas the judiciary would have liked to see him appear before the Assises court, as an accessory to murders committed during robberies which had gone wrong. But his expertise in logistics – not in acting – had saved him from that sort of mess. No evidence, no conviction!

The cell door opened.

‘Come on Dio, let’s go!’

‘OK guv, I’m coming!’

Dio put on a no-nonsense navy blue jacket, over a white shirt with a dark tie. With his imperturbable face and cropped grey hair, he was a picture of austerity. His firm, slightly hollow cheeks were the result of intense daily sporting activity. This sports culture had not been part of his background, but when he took up diving, it had turned into something essential for him: particularly when the diver was caught up in strong currents and had to really struggle to get back to the boat.

He missed those maritime escapades like hell. Just like everyone else from Marseilles, he saw the sea as an integral part of his environment. As a little kid with his grandfather, he used to take their "pointu" – the traditional Mediterranean fishing boat – to go out for a trip to their hut in the Morgiou calanque, one of those deep rocky creeks on the coast just to the east of Marseilles. Sometimes they would catch a few sea bream or sars that his grandmother would grill for breakfast, and which they would eat outdoors, with a view over the Mediterranean. Within the space of a few years, the traditional residents of those enchanting places had been requested to pack their bags, to be replaced by hordes of tourists with scant respect for anything.

Ever since, Dio had loved to go to Les Goudes, a former traditional fishing village on the calanques, to dive with his friend Georges who owned the Scaphandre, a small diving club which had not always been there. The start of that had been when Georges bought up a restaurant on the verge of bankruptcy which was ideally located on the seafront, with direct access to the port. At the time, there had been rumours of certain sorts of pressure being exerted on the restaurant-owner: it was rumoured that he had been “persuaded” to make over the property to Georges and his Belle-de-Mai friends for a "fair price".

With the help of a few modifications, it had been transformed into a spartan auberge, with dormitory-style bunk-beds. Meals were taken canteen-style, with everyone sitting around the same table to consume the single menu prepared by George's wife, Monique. For sea trips, the club had an old fishing boat converted for use by the divers. But it was also pressed into service to convey certain "friends" who were in trouble with the Customs, the police and all those bent on spoiling their trafficking fun.

This was where Dio learned to dive and where he passed all the grades that enabled him to flirt with the sixty-metre-depth mark without too much danger. There was no question of risking a control, or even worse, an accident, and getting his friend into trouble. Because at the slightest glitch, you have the whole administration down on you like a ton of bricks, with firemen to the rescue, the judiciary looking for culprits, and so on and so on. Even a possible false alarm is bad for business. Dio defined himself as an "architectural" diver, meaning that he admired the great submarine arches and the tunnels sculpted in the rock, everything that has been built by nature. He was no fan of "commando-style" diving, with frantic flopping of flippers to see as many things as possible. No, what he preferred was to let himself be carried along with the current, following schools of fish in a state of weightlessness, like a baby in its mother’s womb.

The Scaphandre also belonged to him a little, because George was a childhood friend who had grown up like him in the Belle-de-Mai district. And, like all the neighbourhood kids, he had had a number of setbacks in business. A bistro opened then closed. Ditto a restaurant. A shop sold at a loss ... The list of Georges’ failures was long. But he had managed the feat of never once being convicted: a real feat for a kid from that district!

In the eighties, after all these failures, he had decided to leave Marseilles for sunnier skies, where he could look after his "bizness" without being bothered. He sailed off for Egypt, more specifically to the south of Hurghada, to Safaga, where a Belgian friend had opened up a diving club for tourists in search of adventure in the Red Sea.

There Georges launched his first campaign to acquire the diving instructor qualifications which were necessary to ply the profession. He proudly framed them and hung them up on the wall of his office. For this son of an illiterate Polish labourer, those qualifications were his way of getting his own back.

When he moved back to France, Georges had acquired a skill but had no money. Unlike Dio. Their fellowship could only be mutually beneficial and it had stood firm for over twenty years. Despite the unrelenting efforts made by the police to try to nab George, with raids, searches and inspections by both the fiscal and the national insurance cover authorities, nothing worked. The business set-up devised by Dio prevented any possible discovery of the secret funding of the Scaphandre. The honest, honorable business catered for over five hundred divers a year.

The friendship between the two men made them unassailable; they knew what they were for each other. And if Dio was able to buy extras at the prison shop, it was thanks to George, who sent him the necessary money to ease his life in prison. Where did the money come from? Perhaps Georges also served as a "laundry" for his Belle-de-Mai friends...

Dio left his cell and walked along the first corridor; then came the first door, the slamming of the large electromechanical lock. Followed the whole time by the warder, Dio went along other corridors and then through the double exit door, out to the transfer van. At each control-point, he repeated his lock number, like a magic password, which only served to go round in circles or to go to court.

‘Get in!’ ordered the police officer.

Dio sat down and was handcuffed to the vehicle. It drove slowly out of the prison. Dio looked out of the window; it had been some months since he had last seen the outside. Today, the sun was out for him. The bus was waiting, as usual. The van left the car-park, turned left, then right and joined the motorway. It was something like countryside, near Roissy Airport and its aircrafts, where houses were rare. What with the cars and the planes, the decibels were guaranteed.

In the distance, Dio could see the huge parking area of the Aulnay PSA car factory: it was half empty, as the cars were not selling too well just then. There were few cars on the motorway. A sign indicated the Bobigny exit. Already there. Sounds of doors opening and closing.

The van stopped, the officer beside him leaned over and detached him. During the trip they had not exchanged a word.

‘We’ve here, get out!’

He was flanked by two policemen. Together, they entered the court through a back door. Dio thought fleetingly of Chaïn and his hidden door in the Strasbourg Post Office. They went up the stairs. A policeman walked ahead of him, and then he entered the glass cage.

‘Sit down!’

Dio sat down and looked around the courtroom; it looked nothing like the one he had known in his youth. This one was modern and well-lit. Facing him were the plaintiffs and the Procureur – the public prosecutor; and to his left the public benches, which were sparsely occupied. It must be said that trials for drug trafficking offenses were commonplace in the Seine-Saint-Denis département. Especially with Roissy and its international airport nearby. As a stopping-off point for mules – drug couriers – from South America or Africa, it is the start of a well-marked trail: the disembarkation, the Customs, the X-ray for those who had ingested the drugs, the sentence handed down by the Bobigny court and the imprisonment in the gaol of Villepinte.

Maître Brasil, his lawyer, turned and came over to shake his hand.

‘How are you?’ he asked.

‘Well, we'll see later!’

‘Don’t worry, it should be okay, they haven’t got much to go on!’

‘I know, but their default setting is as much as they can give me!’ Dio answered, a little tensely.

The lawyer tapped him gently on the hand and gave him a knowing smile, then went to sit back down again.

A few people entered the courtroom to listen to the judgments being handed down; often out of simple curiosity, but were they one-timers or regulars? Dio knew none of them. Anyway, his family was in Marseilles and, depending on the verdict, he would ask either to be transferred there or to finish doing his time here.

‘Ladies and Gentlemen, please stand for the Court!’ enjoined the clerk of the court on duty.

Everyone stood up. "A chick as Head Judge…, Madame la Présidente! Things are really moving in the justice system," thought Dio to himself as he stood up.

‘Please sit. Clerk, go ahead.’

‘Sergio Nardi, born October 30th, 1954 in the third district of Marseilles. Unemployed…’

Dio was no longer listening. Now he was here, he hoped things would go fast. He was tired of waiting. He was eager to be able to start working on the idea that had germinated in his brain while watching a TV show about Navy commandos.

While the facts of the case were being read out, Dio was at Les Goudes. Thinking about diving helped him to relax; since what was going to be said was right anyway, what could he do about it? That’s what his lawyer was there for.

‘Monsieur le Procureur, you have the floor!’

‘Madame la Présidente, the individual appearing before us today is one of the obscure but far from low-ranking members of organised crime. He is extremely intelligent and has decided to use his capabilities in the service of evil. It is true that today, we are trying him for acts which are certainly serious but still relatively benign: 500 grammes of cocaine found in a car boot, that’s nothing in comparison with his past deeds and his associations...’

"He's dead right there”, Dio thought. “If I hadn’t borrowed that car because I was in a hurry, they would never have nabbed me. But it has to be said that, that night, I had to get back to the hotel real fast and there was no taxi in sight. So when Jacky the Science offered me that car, I agreed without a moment’s hesitation. I’d been driving for five minutes when two unmarked cars blocked me. Armed cops were pointing their guns at me. They hauled me out of the car, hands on the bonnet, body-search. A cop opened the boot.

‘A nice package for Dio, eh?’ sneered the cop from the open boot.

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about!’ The cop came to me and stuck a white package wrapped in plastic under my nose.

‘And that's flour, I suppose?’

‘If you say so!’

I quickly realized that that was the end of my freedom for a few months. I’ll never know if that coke was in the boot by accident, an "oversight" as it were, which is something really rare in the profession. Or if it had been put there on purpose, to frame me. Had some bastard grassed on me? Probably, because I don’t believe in chance. But why? I was always legit with the Parisians, especially with the Montreuil gypsies. Unless the fuzz had managed to bribe one of the hordes of small-fry dealer-addicts. But I didn’t believe that: half a kilo of coke, they never had that much to sell. On the other hand, that the drug squad might have slipped it into the boot, that was certainly possible. Anyway, when I get out, the truth will also come out."

‘In consequence of which, Madame la Présidente, I demand the maximum penalty provided for by the law, that is to say, five years' imprisonment, of which two years suspended.’

‘Thank you, Prosecutor, the floor is yours, Maître Brasil.’

‘Madame la Présidente…’

"Fucking hell! Five years! He’s really laying it on! Well, let’s do the maths: if I get three years firm, I’ve already done one; with the standard remissions, that’ll make it at the very least seven months less, and with the extra remissions four more, so that makes it eleven in all, almost one year. So at most, I’ll be out in a year."

‘And that, Madame la Présidente, is why I ask for my client’s time in custody to be commuted to a one-year sentence,’ concluded the lawyer.

‘Thank you, Maître. Mr. Nardi, do you have anything to say to us?’

‘No, Madame la Présidente.’

‘Very well, we shall withdraw to deliberate.’

‘Please stand!’ ordered the clerk of the court.

Dio rose and followed the policeman. Behind the door was a bench with rings set in the wall.

‘Sit down!’ The man in blue’s order called for no comment.

The policeman took his wrist and handcuffed it to the ring.

‘Can I smoke?

‘No, it's prohibited!’ The curt tone was final.

"Not too chummy, is he, this cop; yeah, guess it’s normal, escorting a guy isn’t that much fun: it appears that soon it won’t be up to the pigs any more, it’ll be the screws that’ll be doing the babysitting. They must be thrilled!"

The policeman, who had gone outside for a smoke, came back in.

‘You can go if you want.’

‘It’s okay, I'll stay here, they shouldn’t be long, the case is pretty simple, said the policeman, looking at Dio.

‘I agree’ replied the latter, with a slight smile on his lips.

‘Come on, lets' go.’ The cop stood up and detached Dio. They entered the glass cage together.

‘Ladies and Gentlemen, please stand for the Court!’

"Well now we’ll know!" thought Dio, making to sit down.

‘Kindly remain standing, Mr. Nardi!’

‘I’m sorry’, he managed to stammer.

‘In view of the charge …’

"Pretty cute, that judge”, thought Dio to himself. “Probably in her early fifties… And what if I slip her my phone number when I leave, who knows?” – he laughed to himself – “But right now I don’t have that much spare time, business you know …"

‘… In consequence of which, the Court sentences you to three years in prison, of which two years firm and to a fine of € 50,000.’

‘That means I’ll be out really soon!’

‘It’s great, isn’t it!’ exclaimed the lawyer heartily.

Dio was dazed, he couldn’t believe that the court had not sentenced him to more.

‘Yeah, sure, but why?’

‘Because they couldn’t give you any more, you haven’t got a record!’

‘But what about the little problems I had as a kid?’

‘They couldn’t take those into account; even if they had wanted to stick even more time on you, it just wasn’t possible!’

The lawyer picked up his things while Dio followed the police.

‘I’ll come and see you next…’

Dio did not hear the end of the sentence, he was elsewhere.

‘Some people have the devil’s luck!’ muttered the police officer taking him back to the van.

‘You can say that again!’ echoed his colleague.

"Not happy are they, the pigs, but in their shoes I’d be pissed off too, because with all the remissions, in a month I'll be out."

‘Come on, let’s go home!’ said his one-day attendant.

The return trip was more cheerful for Dio, he had a smile on his face. He almost felt like having a good laugh with his guardian angel. But he sensed that he would not necessarily appreciate the joke.

After the usual administrative formalities and rigorous body search, Dio regained his cell. The warder locked the door. After waiting for a few moment in case he came back, Dio opened a large book from which he extracted a slim mobile.

He switched it on and typed a brief text message: "I'll be out in a month so no more messages because I’m selling the phone. We’ll be in official contact. Dio", and sent it. The message was for George, who would see to informing "the family". He always avoided speaking because sometimes walls have ears. A text message is just as effective, it forces you to collect your thoughts and go straight to the point. And it makes no noise.

He switched off the phone and put it back in its hideout: this was no time to get caught, just before he was about to leave. He was at last able to concentrate on his project.