Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: 404 Ink

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

When an ex-catholic woman develops a sexual relationship with a vampire, she is forced to confront the memories that haunt her religious past. Struggling to deal with the familial trauma of her Catholic upbringing, hotel cleaner, Noelle, travels to the Isle of Bute. There, she meets a man who claims to be a vampire, and a relationship blooms between them based solely on confession. But as talk turns sacrilegious, and the weather outside grows colder, Noelle struggles to come to terms with her blasphemous sexuality. She becomes hounded by memories of her past: her mother's affair with the local priest, and the part she played in ending it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 422

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

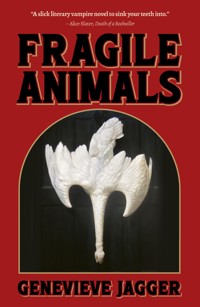

Praise for Fragile Animals

“Gorgeous and gothic.” – i-D

“A slick literary vampire novel to sink your teeth into. Hot!”

– Alice Slater, author of Death of a Bookseller

“To read Jagger’s prose is to be riven; like the call of the ocean, one gazes into the story and becomes engulfed – Fragile Animals invites the reader into an awakening of the self which feels at once violent and immobilising.”

– Elle Nash, author of Deliver Me

“Shirley Jackson meets The Wasp Factory. Fragile Animals is bold, beguiling and breathtaking.”

– Carrie Marshall, author of Carrie Kills A Man

“This book took me on a wild ride and I was absolutely obsessed with it.”

– Emily Dowd, NetGalley review

“Captivating and unique … I genuinely can’t believe its a debut.”

– Poppy Kimish, NetGalley review

“Every single page, every chapter made me absolutely feral with anticipation with what’s to come next.”

– Cecily Co, NetGalley review

“First word that comes to mind thinking about this book is just… wow.”

– Alexandra Gilliam, NetGalley review

Published by 404 Ink

www.404Ink.com

@404Ink

First published in Great Britain, 2024

All rights reserved Genevieve Jagger, 2024.

The right of Genevieve Jagger to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining the written permission of the copyright owner, except for the use of brief quotations in reviews.

Editing: Elle Nash

Proofreading: Heather McDaid

Typesetting: Laura Jones-Rivera

Cover design: Luke Bird

Co-founders and publishers of 404 Ink:

Heather McDaid & Laura Jones-Rivera

Print ISBN: 9781912489961

Ebook ISBN: 9781912489978

404 Ink acknowledges and is thankful for support from Creative Scotland in the publication of this title.

Fragile Animals

Genevieve Jagger

Contents

When In Doubt Run Away

Salt

The Confession

Lake Mirror

Careless Homosexual

Women Of The Jugular

Haunted

Alive Like a Candle

It’s True I’m Terrified

Gore Me Like A Peach

Ascent of the Blessed

Toulouse

Ghost Angel

Bitch

All the Time

Lovers

Fall of the Damned Into Hell

Cockheart

Goodnight Prayer

Take Me Apart

Red Inside Myself

Oranges Are The Only Fruit

Cygnet

Judgement Day

You’re Not Sorry If You Don’t Beg

The Truth Will Always Be Purgatory

Love List

About the Author

for that little girl crying in bed

When In Doubt Run Away

I have many wounds from the cold thing called claustrophobia.

Bruises on my thighs, lungs that cottonise in the winter, a myriad of snippeting scars, hidden in creative and domestic places across my body: the armpit, the back of the knee, the groin. None of them are sincere, none gouged too deep; most unclear how they even came to be. Standing at the edge of the harbour I am inclined to wonder if whatever mark coming will be more of the same. This trip, a little nick, a short bleed, before heading home again.

The ferry leaves me behind, travels homewards to the mainland, cracking the glass of the water as it goes. After some time, the fog intervenes and the entire hulking force of the boat is eaten by the sky’s grey mouth. I once read somewhere that winter does not officially begin until December 21st, but in Scotland we are barely past the first blows of November and the clouds in their closeness have descended. The wind on my bare skin feels like white alcohol and teeth. I slip my hands beneath my jumper, press my fingertips between my ribs. It’s shivering season. My mood shivers too.

I had a brief flash of decisiveness last night. Of course, I knew what I was doing, when in the drunk depths of the smallest hours, my fingers typed in ‘travel’, and all the websites with their slot machine buttons appeared. My mattress and breath were beginning to smell the same and the disgusting fact of that had galvanised me. It was 3am and God had left his post. I spun the wheel of possibilities. It landed on the Isle of Bute. Little island. Clean winds. A quieter place. I threw up my room trying to pack, took my notebook from my nightstand, spent an hour searching for a pen, then walked to the 24-hour shop to buy a new toothbrush, passed out with it still cupped in my palm.

Now, my hands, of their own accord, are excavating my pockets. No cigarettes. No phone, because I left it where I’d thrown it, lying reproachfully beneath the radiator in the corner of my room. No sense of direction because I’ve never had that. Creeping up my spine, the feeling of a blunt knife is edging from vertebrae to vertebrae, anxiety threatening to cleave my muscles apart.

The harbour ground is sodden from the air itself, which is cold, penetrative to the bones of my fingers. I stare out at the water for so long – not an ocean, yet still undulating and dark. In this time the sky observes me then shakes its disinterested head. Finally, my stiff feet turn from the water to face the town, the craggy, old stone buildings. Rothesay, the bleak button nose of the Isle of Bute.

First foot, then the second. Inched with force. Aching. Moving. It takes more than a moment, but eventually I am walking normally – or how I think normal people walk. It has something to do with the swing of the arms maybe, a certain pace that is not skittering nor hunched.

The small shape of this world is a decision I have made for myself.

In the sunshine, the town could be sweet, with boutiques and chip shops lining a brief promenade and houses mounted like paper crowns on the unassuming peaks of hills, but the sky is stony and low, and almost everything fits within the width of my peripheral vision. The place is small. Small enough that everything closes on a Sunday, a fact enforced by the church bells that clang dimly through the muffle of the fog. That sound… Big He is at his watching post again today. Overseeing through the haze of His clouds. None of the people wandering down the wide flat streets seem to mind. They keep their heads bent as the tolling of bells fades out.

I realise with some horror that without a map and a phone (a phone), I am going to have to ask someone for directions.

Bakery, bus stop, baby boutique. Closed. Most people are friendly in a rude way, keen to ask questions, to stare with open suspicion at my unfamiliar face. They offer little and linger long, keeping me standing, nodding, then giving no information. Eventually I walk through an open door, the only one open along the street. A bell jingles. The rusty smell of blood engulfs me.

‘Yer staying at Baywood?’ the butcher asks. He’s bald and sweet-faced, with a little white cap upon his pockmarked head, peppered hair tufting out the sides. ‘That’s away into the hills. Are ye walking?’

He eyes my suitcase as I nod, then shakes his head in a way that irritates me. A silence draws out long and terminal until I ask, ‘Is there a bus?’

‘Nah, ye’ve missed it,’ he says, and walks round the counter, flips the open sign on the door to closed. Does not actually close the door.

‘I’ll give ye a lift.’

I don’t feel so strange coming here without a phone. Most people I know won’t notice if I’m gone for a week. Until recently I’ve had a flatmate and a half.

The half is long gone, all trace of her disappeared, apart from a few remnants in the medicine cabinet that seem too nice to throw away. Washes, gels and creams, scented with things like chamomile or clementine; a few half-finished blister packs of iron tablets that I can’t remember if I was prescribed and she was taking or if it was the other way around. She left a Mooncup too. Thin, stringy film still clinging to the rubber rim, blood gone brown as the iron pills. I have trained myself not to look at it because it’s too disconcerting. Too jarring to see blood so casually and blood that is not mine. Every time I open the door, it has progressed further in its rot. As such I have not managed to throw it away.

My other flatmate is the whole. That’s Eddie. Eddie is a gay, deep-voiced smoothie shop manager, also studying for his master’s degree in supply chain management. He was the first person to respond to my ad about looking for a flatmate and so we are flatmates now. We have a casual friendship in which I do not see him much, if at all. I sometimes hear him come in at 5am and change from his thigh-high latex boots into the smock he wears for his smoothie shifts. Once every couple of months Eddie and I will spend a night together in the flat, usually out of some mishap in Eddie’s social life, like a missed bus or a snowstorm, with a few of Eddie’s friends and a myriad of spirits. One time, sitting at a full kitchen table with Eddie’s friends – who cackled about things that, if I ever went out, I’d know about – I asked Eddie why he stays out so late all the time when he knows he has to work the next morning. Eddie said sleeping was ‘homophobic’ and that I should mind my own fucking business.

‘For someone who’s always drinking, why do I never see you drunk?’ Eddie demanded, smacking the table. Then he fed me knock-off Bailey’s shots until I puked sour milk through my nose.

My point is, Eddie won’t notice I’m gone. Our relationship is more or less a means to afford the city. A lot of times it feels like living alone and I so wait up to hear Eddie’s key in the door, a reminder that I’m not. The only person who might notice my absence is Lorne, my friend, my almost-uncle. Though recently I’ve felt Lorne could quite easily do without me.

Not that I plan to be here that long.

Not that I really plan anything at all.

The butcher’s van smells like a butcher’s van and we are bundled together, along with my suitcase, into the tight-seated cab.

‘Come a long way?’ he asks, over the croak of the engine. He catches my eye in the rear-view mirror as I worry my tongue against an ulcer on my gums. There’s another in the right side of my cheek.

‘From Edinburgh,’ I say.

His eyes dart from the road for a minute, as he gives me the once over. ‘That explains a lot,’ he chuckles. I frown at him, but he doesn’t notice. The engine grizzles as we drive along the coast.

The weather makes the water appear endless. Technically the water offshore of Bute is a firth, or an estuary, but with the fog in the way, it looks like it could go on forever. Logically, I know a crowd of mountains sits just behind the mist, the beginning slopes of the mainland, but the distance makes my stomach sour. I focus instead on the opposite window, looking past the greasy profile of the butcher to the view on the other side of the van: greener, safer, lots of trees. Houses of incongruous design with sleek extensions built onto their old stone bodies, all pebble drive and solar panels and bright gnomes in the driveway. We pass a kind of church thing with turrets and a crumbling slated roof. Surrounded by overgrowth the place looks as though it was once possessed, but the spirit has since gotten tired and left rooms cold and empty.

After that I see some sheep. Sheep are the same everywhere you go.

As the butcher drives the van up into the hills, I count their woollen bodies. They are surprisingly sparse. High tide and paved coastline turn into fields and moors, land warping quickly though we’re driving slowly past. I have only seen nine sheep. Ten. Eleven. Thirteen. The butcher sticks a finger up his nose and I turn back to my own window.

‘Surprised yer staying at Baywood,’ he says. ‘Most people go to one of the hotels in Rothesay. Fancy down there, and cheap too. Featured in the papers recently.’ He hacks, clears his throat and my fingers reach down to touch my suitcase handle. I insisted on not putting it in the back after the butcher mentioned a recent shipment of veal. ‘I suppose there is still some love for these crooked old places out here, though. My wife put up our spare room for tourists to stay in. Hundred and twenty quid per night and booked up the whole of next spring. This one couple sent a message saying they were coming here to swim. Swim!’ He laughs until it turns into a cough again. ‘This isnae Arran.’

The road rambles on, no traffic except a few lone farm vehicles riding from the fields back to town. There are more tractors here than power lines and we’ve not passed any cars either. This is the kind of place you go through, I think, passing by to someplace else – but then that doesn’t quite make sense because there’s nowhere to go from here. It took me three lines of transport just to arrive at this dead end. This is a separate place, I’m thinking, stagnant, by itself, when we turn abruptly into a long grey driveway and are confronted with the hard fact of a house.

‘Here we are,’ the butcher says.

‘Thanks.’

The house is made from stone but painted an ill pale pink at all the doors and fixtures. The pop of colour makes the stone look surly. The front of the house is dotted earnestly with potted plants, some painted on the sides with pink things like flowers, little birds, but anything growing has been tamped down by the November chills. Dead for a month, at least. The sky won’t hold its weight and the fields are minding their own business. There is only one car parked in the driveway – an ancient Mini Cooper in matching baby pink.

After I have pulled my case from the van, slamming the door behind me, the butcher leans over the seats and winds down the window to shake my hand. He holds it longer than necessary and says, ‘That’ll be a tenner, darling.’ Then he guffaws and ruffles my hair. He yells ‘ciao!’ out the window and drives away. I pat down the static in my hair and stare up at the contradictory building. I peer through all the windows, trying to decide whether or not to go in, waiting for something to stir me. Behind each pane of glass the house is dark. A magpie settles on the guttering and assesses me with its swivelling eye. It hops behind the chimney as though looking for a friend, then reappears alone.

The front door swings open and an old woman in a magenta dress beckons to me.

‘Are you coming in?’ she shouts. ‘I’ve been watching you for the last five minutes.’

I struggle to answer.

‘Come on! Come on! You’ll catch your death of cold!’ She flaps her hand at me, smiling despite the annoyance of her tone, and I surge forward as if caught on a line. When I am close enough, the woman grips me by the shoulders and pulls me into the house.

The smell is instant – worn, dusty fabrics and eggs fried hours ago. It climbs in through my mouth as I climb into it, making me feel as though I have been swallowed, licked up by the wet tongue of the woman’s grasping fingers. My case makes a thud on the floor at the same time the door clicks shut. Closed jaw. No decision necessary now. I am consumed by the mouth of a house called Baywood.

I find myself in a busy, low-ceilinged kitchen. Most of the floor space inside is taken up by a messy kitchen table that makes the floorboards creak as if it’s shifting from foot to foot. The woman takes my coat from my shoulders then grabs me again with both hands. She pulls some winged spectacles from her head as she tries to get a better look at me. Over her magenta dress she is wearing a magenta cardigan and a magenta apron and under it she has some woolly magenta tights. At her ears are pink, pearl clip-on earrings and on her chest is a necklace that seems to have been knitted.

‘Miss Fraser?’ I ask, a name inexplicably remembered from the booking website. Miss, not missus, never wed.

‘Oh, please, call me Cairstine!’ she says, rolling her crinkled eyes. ‘Miss Fraser is my mother.’ She sticks her tongue out mischievously and giggles before patting me like a child. ‘Please, pet, please take a seat. I love it when we have guests on the island. What’s your name again? Noleen?’

‘Noelle.’

I stand a moment longer and she busies herself with a kettle and teapot. She’s wearing purple slippers and they slap against the floor as she moves around. I don’t want any tea, but I pull out a chair anyway. It has a little cushioned cover on the seat, embroidered with weepy-eyed Scottie dogs. I feel a smidge of guilt as I sit upon their heads.

‘You’re late, lovey. Do you know you’re late?’

My hands are limp in my lap. The clock on the wall has a different kind of fruit representing each number. It’s Apple o’clock. Outside the light is sinking fast.

‘I’m sorry. I didn’t know there was a check-in time. I got a little lost on my way in,’

She turns to me. ‘No, no! Don’t be sorry. I’d rather you came when you felt ready to come. I’m just surprised it’s so late. Not everyone is as urgent as I am. Some people like to dawdle. That’s the wonder of people isn’t it – their differences. Me, I’ve always been too punctual for my own good. Don’t worry about it, darling, don’t worry.’

Miss Fraser’s slippers slap, slap, slap as she arranges our teacups, plopping two sugar cubes into each one without asking. She sets mine before me with a flourish, knocking a little tea out into the saucer. The cups are not pink, but they feature pink piglets, running daintily along a porcelain field of grass. There is nowhere to put it down on the table, so covered in magazines and tissue boxes and initial preparations for dinner, that I am forced to hold the saucer in my hand. Miss Fraser watches me until I take a drink, malty and fat with whole milk, and then, at a loss for what else to do, I give her the thumbs up.

Behind her head on top of the cabinets is a row of discoloured appliances. Two kettles. A toaster. What could be a bread maker but may also be a rice cooker (my bet is on bread). The appliances lean against each other, plugs hanging heavily over the side, clearly having sat long in disuse. On the side of the counter, Miss Fraser has a bag of processed white bread, half-eaten with the cellophane tied at the top. I think a little prayer in memory of her bread machine who is forced to watch this barbaric betrayal.

Miss Fraser settles in beside me and takes a drink from her teacup. She puts her pinkie finger up, all genteel. I watch her watch me notice.

‘So!’ She breathes, clasping her hands together. ‘What brings you to Bute?’

‘Well…’ I stare into my teacup. The milk is swirling in flecks on the top. ‘The city was getting a bit much, I suppose. Lots of people.’

She nods knowingly but appears not to have heard me.

‘Where do you come from, dear?’

‘Edinburgh.’

She nods deeper, with noise – little mm-mms. ‘I can see why you’ve come. You’re very pale. I see so many young people coming in from the city, you know, for the colour. We have good wind out here – those cheeks will come alive in no time.’

I’m about to open my mouth but she continues, ‘You’ll be feeling much better once you’ve had a good, hot dinner. I’ve cooked too much but what can I say – I’m a feeder. I shouldn’t call Baywood a bed and breakfast. It’s a bed, breakfast, lunch and dinner. A hotel really, only I don’t clean all your bits and pieces. I hope you like shepherd’s pie. You’re not a vegetarian, are you? I can’t stand vegetarians!’

I smile and take a large mouthful of tea to remove the possibility of responding. Not necessarily because I don’t like her, just my brain generally struggles with responses. If I finish my cup, I suppose she’ll show me to my room and I would be spared the banality of my conversational discomfort. However, Miss Fraser requires no response and ploughs on without me, gesticulating with that pinkie kept up.

‘You’re in the quiet point of the year by the way, though Baywood runs a very tight seasonal schedule. You should see the folk that come at Christmas. It’s the same people every year and they just love it here. All couples and their young children. The children beg to come back every winter because they say it’s like family – and they love my cooking. I’m an excellent cook. Don’t even get me started on the soap makers who come in the spring,’ she laughs, ‘they’re big fans of what I do out here.’

‘I thought there was only one room here?’ I ask.

‘No, dear. There’s two. Plus, I have some futons as well. A man I used to know in Japan gave them–’

‘I thought there was only one.’

‘Hm?’

‘On the website – it said there was only one bedroom.’

Miss Fraser looks at me absently. ‘Well,’ she says, ‘that’s not correct. There are two rooms here and they’re both occupied so that makes us fully booked. There’s another man and you should see the state of him! Just like you, a sickly thing! Dear god, his pale face!’

It’s a Sunday and she’s taking His name in vain. I don’t mind, it’s kind of funny, but I do fear that He’s listening. Tracking me like Santa Claus but more sinister. Bigger implications than just a piece of coal. I stand. ‘I should put away my things.’

‘Of course!’ Miss Fraser blusters, standing to fuss with my case. ‘You’ll just love your room. I can’t wait to show you it. It’s got the best radiators in the house, and when it comes to bedding, I don’t skimp on thread count. It’ll be the most fabulous room you’ve ever stayed in. I’m sure.’

‘It’s okay,’ I say, and take the bags quickly before she can grab them. She notices, looks up and blinks, before giving me a wry smile.

‘After you, Noelle,’ she says, gesturing to the hall and the stairs.

I blush, feeling caught out.

‘Thanks.’

Miss Fraser talks for a long time about extra blankets and towels and pillows. I feign menstrual cramps to get her to leave. In truth I haven’t bled in months.

The room is functional, agreeable, but quite plain. The wallpaper is light blue and adorned with tiny thistles. The windows are larger than I’d like them to be and allow the moonlit darkness to intrude. A large cast-iron bed frame takes up much of the space. The cold of it shocks me when I lean against it. Even the wood of the dresser is oddly cold, as though it has been allowed to ossify untouched, for a lifetime. Despite Miss Fraser’s claims of seasonal business, I can’t imagine another guest having ever slept in here. It seems too vacant somehow for the soap makers. I can’t picture them having faces. The long mirror seems startled to have me looking in it, my weary presence interrupting its previous still. I too am startled by how I’ve come to look: the grease of my unbrushed hair, the purpled skin mourning sleep beneath my eyes.

With the door closed the room detaches itself from the house. The parts of me I tried to leave behind on the mainland suddenly sail across the water. They make smearing wet patches of condensation on the window, pawing at the pane to get in. I look out of the clear blotch of glass they leave behind and see nothing but the blackness of night. No moon. Nil. The lack of street lights makes the whole world look like a void, and I stand, dumb, at its centre.

Salt

I swear to God, I can hear the rush. I hear it everywhere I go.

In my little room on the cliff in Crail, in a house that was not big but had air and faced the beach, it sometimes felt as though I was growing up on the very edge of the world. It’s not a feeling I could have articulated at the time but it was there, growing at the speed of my core. Past midnight, all the neighbouring lights would blink out around our house and the moon would come and go as it pleased. To me, aged nine, there was nothing more terrifying than a total lunar eclipse. When the ocean would command the totality of His power and there was no escape from its obsidian rush. Without the moon all light was stolen, recycled and reborn as sound.

The ocean.

The ocean on the east coast of Scotland had a horizon so clean and blue that on a bright day it looked as though you could sail right off it. My father had pinned a map onto my bedroom wall and I used to stare at it in disbelief. He’d marked Crail out for me with a little gold pin, the only one on the map. I didn’t understand how the sea outside my window, a sea so self-possessed and incomprehensible, could be considered small in the scale of the world. She was the North Sea. She had the power to swallow me a thousand times over and that would only be a portion of her power. The sound that kept me awake all night was produced by just a slice of her. According to the map, Denmark sat just beyond the horizon, at conversation’s distance to me. I believed my world was huge and it wasn’t. That led me to the conclusion that I am small.

The ocean and I were raised as twins, and it seemed clear to me which twin was preferred. As soon as I could walk, I was made to swim. As soon as I could swim, I could hold my breath in brutal autumn water, perform somersaults and handstands in the spring. All of my clean socks were filled with sand. You could taste the water on me, on my skin and in dank locks of my hair. When I was small and bored in church, I would sometimes lick myself for the taste of brine and in that way I came to associate the taste of salt with the taste of God. Combined with the rushing sound that poured in through the windows during quiet sermons, the ocean seemed just as all-knowing.

I was supposed to love the ocean. And yet. When the sun died each day and the roaring black rolled in, when the world regressed back to creation and any wills within me gave themselves over to the endless hymn of the tide… I found myself cowering. It’s the same shiver that comes over me now as I look out the window of Miss Fraser’s guest bedroom. The shiver of a child who has swum out too deep, whose foot can no longer touch the bottom. A child who is dripping cold now crouched inside my body, leaning on all my sentimental parts (which, of course, is all my parts).

I would drive fingers into my ears but it’s pointless. There’s no escaping that frozen girl. She’s lying. Listening. Desperately awake. She’s licking herself to taste God.

The Confession

I meet Moses just outside my door when Miss Fraser rings the bell for dinner (there is a bell, apparently). That’s what he introduces himself as to me, Moses, a note of embarrassment in his voice as he offers one large hand out for me to shake. His fingers are long with high-strung and particular joints, I am immediately aware of their tendons. His fingernails are dirty, each one lined with a crescent moon of black grime, and when I look to the lines of his palms I find long crevices, sinews of dirt.

I am so jarred by Moses’ hands I forget to react to their gesture. My arms hang lamely at my sides until, eventually, he lets the offer fall. My head is bent and Moses stands before me, barefoot.

‘Noelle,’ I say, a beat too late. A beat in which both of us suffer.

The man is older than me by decades, though it is hard to pinpoint in his waxen face how many. Fifties seems safe, but if you pushed me, I might go a decade older. Maybe a decade younger. Maybe I just don’t know. Miss Fraser was right – he does look unwell. He’s sallow, sick skin amplified by a head of unruly hair, a dense bracken of slate grey. Like the kind you’d find on the haunches of dogs, thick hair for an older man. His eyes are dark as he smiles at me, and I see the contradiction of his feline mouth. It splits his face like a chasm as it curls up into a smirk.

The overall effect is a face that is dominating, thoughtful, ridden with something like fleas.

‘It’s nice here,’ Moses says, more as reassurance than statement. My eyes move down to his neck where the name Emilia is tattooed in looping black cursive, beginning at the skin on his Adam’s apple, and ending in the pale space below his left ear.

I nod at him vaguely before turning to the stairs. Moses is courteous enough to wait a few paces before following me down to the kitchen.

Dinner passes in a fit of silence for everyone who is not Miss Fraser. She explains her shepherd’s pie to us bite for spooned up bite, pointing out the breadcrumbs, which she has crumbed herself; the potatoes, which started sprouting in the cupboard, but had maintained their taste as if fresh; and the minced lamb, described with elation, bought on offer from the butcher’s shop. Moses attempts to interrupt or respond more than once, and in fairness, Miss Fraser entertains him – but it is clear she doesn’t care whether he speaks or not. She considers herself one conversationalist with the power of three, and the relieved weight is all I could ask for. I chew and mmm and listen to her, disinterested in Moses’ contributions as well.

Once the meal is done and all of the plates are washed and cleared away (Moses cleaning quickly and keenly), Miss Fraser announces she’s heading to bed. She advises we do the same.

‘I am very particular about bedtimes,’ she informs us.

The thought of lying in my bedroom alone with the ocean haunting every small sound makes the sour of my stomach rise. It’s enough that I am forced up to the bathroom, to the toilet, where I can release my pained bowels. It all slips out too easily, as if my body contains no digestive tract, just a deep and churning void. Fearing that everyone can hear the sound of my liquid shit emerging from my body, I pull my two bum cheeks apart. The act is oddly comforting.

Once everyone is securely in their rooms I creep downstairs again and resume my place at the kitchen table, this time with a pen to click against my teeth, the blank pages of my notebook open as an uneasy companion.

Last night when I wanted a reason, what I told myself was: I am coming to Bute in order to write. Or rather, re-write my second book of poems as Lorne has demanded I do. Lorne is my friend, my almost-uncle, but he is also my editor and publisher. I write poems and Lorne commits autopsy and prints them. We are a small scale but effective duo. Growing a large enough audience with the first book (like 50 people), we have the attention to justify a second (this feels like a lie but Lorne says it isn’t).

We still work part-time jobs at full-time hours in order to get by. Rent persistently exists and someone’s got to put milk in the fridge to go sour. Lorne is a bartender, and he looks sleek in a black T-shirt. I clean hotel rooms in Leith. Or I have done for a long while now. I don’t feel very good about the word ‘poet’. It’s a version of myself I find difficult, I’d much rather think of myself as a cleaner. Something about the declaration of poet-hood makes me feel, in my guts, humiliated. I don’t even read poetry, I really don’t. Yet I have one book out and seem to have committed to writing another. None of myself makes sense to myself.

Still, Lorne demands the second book is re-written. He found my first draft ‘vapid’. I thought if I came here to do it, it might just happen, purely in relocation alone. The logic being I do not have any routines here in Bute, so I suppose the routine could be writing. This trip would be a gift to myself, the splendour of the lands might inspire me into making something (anything), and then maybe I’d come away with a fresh book for Lorne.

My blank page shrugs and continues to be blank.

There’s a soft click at the kitchen door before Moses enters. He has changed from his dark shirt, dark trousers combo into a dark green T-shirt and similarly dark tartan pyjama bottoms. He is still barefoot, though it is cold in the house, and there are wiry black hairs on his toes, almost pube-like. He cocks his head at my open book.

‘What are you writing?’

‘Nothing,’ I say, removing the end of the pen from my mouth. It is wet and I wipe it on my jeans.

He ducks his head. ‘You’re playing coy?’

‘No.’

‘There’s no one out here to watch you anyway.’

‘I’m not being coy.’ I flash him my blank page. ‘I’m not writing anything, see?’

Moses pretends to hesitate then settles down in the chair beside me. I watch him and, without meaning to, return the pen to my mouth. When I remove it again it is gelled and sticky, the shining cap pointed directly at him.

‘Stuck?’ he asks.

‘Something like that.’`

He puts his hands on the table and there are his specific fingers. The part of the body where you can see the most age. When he fidgets, he looks clay-animated.

‘You’re a novelist?’

‘A poet,’ I say, and my voice drops an involuntary octave. The word will not leave me unless through immense discomfort. I cough. ‘A cleaner, really.’

‘Ah,’ Moses replies, then silence resumes around us.

I find myself saying, ‘I’ve published a book. Working on another just now,’ but I do not know why I tell him this – or why I tell many men this, as though wrapping my arms tight around myself. Moses raises his eyebrows at me. Abandoned to the table, my pen-cap glistens.

‘What do you write about?’ he asks.

I close over my notebook. ‘Nothing.’

‘Sounds interesting,’ Moses says, before rising to flick the kettle on. Life in Baywood exists in an unholy amount of tea. He gestures to see if I want a cup and I don’t but still nod. When in Bute. Moses moves slowly as he collects all the necessary paraphernalia, his body hunched low over the countertop, a steep fold to make up for his height. He has an ugly, crooked spine. It takes a meandering trip up the centreline of his body, the long road to the hairs on his neck.

‘I don’t travel much,’ Moses tells me. Men love to tell.

‘No?’

‘No. I run a business in Aberfeldy. It keeps me pretty occupied.’

‘Oh.’ I am punctuation. ‘What do you do?’

‘I’m a taxidermist.’

The rush of the kettle builds, blurs the declaration enough to make it seem casual. The cups clink as Moses prepares them, giving each one a silver spoon. No noise for the fall of the teabags. Then just that boiling water roar.

‘You sell dead animals?’

Moses corrects me. ‘I stuff dead animals. Then, I sell them.’

I breathe, ‘God.’

‘You’re an animal activist?’

‘No – just where do you get the bodies? I’ve never really considered how that might work. Surely you don’t hunt them yourself?’

He shakes his head. ‘I only use what’s already dead.’

The kettle rediscovers its silence. Moses lifts it to pour, and the hot water fills each cup. Hot water makes a different sound than cold, especially in the act of falling. It is intimate and high pitched, soothing and seductive. Cold water will kill you if you stand in it for too long. Only takes a minute.

Moses sets the mugs down on the table. I have nothing to say to him about using what’s dead, there just isn’t a feasible response. Isn’t it funny the way people approach you? I don’t think I’ve ever approached anyone like this, at least not on purpose.

‘So, how did this happen?’ he asks me.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Your blockage,’ he taps the notebook. ‘What made you stop?’

‘I don’t want to talk about this with you.’

Some of his eyelashes are grey, mostly they’re a shade away from black.

‘Why not?’

I sip my acid tea and it clings to my gums. Without my noticing, Moses has added two white sugar cubes to my cup.

He squints. ‘Is it embarrassing? Heartbreaking? Then tell me – I love a tragedy.’

‘It’s not heartbreak.’

‘It isn’t?’

I regard him. ‘Very familiar, aren’t you?’

The aged grooves at the sides of his eyes crinkle. They’re the clearest mark of age and a sign that he is like this all the time, the scars of a life well-humoured. He clicks his teeth against his cup when he drinks and seems to be doing so on purpose.

‘Yes,’ Moses says. ‘I am familiar – and you’re stuck.’

I bristle, suddenly severely annoyed by him. My pen on the table has gone dry and greasy where I sucked it. I finally set my teacup down.

‘I’m not.’

‘You are.’

‘I’m not.’

‘You agreed with me just a moment ago that you’re–’

‘Just leave it.’ The outside world is made up of black November squares, as depicted by the frosted windows on the front door. Thunderous rushing in my ears.

‘Sorry?’ Moses says.

I hold my face. ‘I’m tired.’

‘Have I offended you?’

‘I’m tired.’

I stand and pour my teacup down the sink and almost chip the handle setting it down too heavily on the draining board.

He doesn’t stop. ‘I just think it’s interesting. Poems. Autobiography. You must know yourself very well.’

‘I don’t,’ I snap, and pace toward the hallway door. At the last moment, before my hand reaches the handle, I realise my notebook is still sitting on the table, along with my chew-marked pen. Moses, a stack of limbs folded into a chair, watches me return. His gaze is like a creaky hinge, swinging open in the wind.

‘Sit,’ he pleads.

‘No.’

His chasm mouth smiles. It’s so dislikeable, so annoying, so self-possessed, yet captivating in a way that must be stared at. The creases at each side move deeply, interrupting the hollows of his cheeks. But to stare is to have your will taken over. Hating myself, I smile at him.

I return to my seat. ‘So, taxidermy. That’s unconventional.’

Moses searches for something in my face. ‘It’s only half true. The shop went out of business years ago. It was a family business you see, but I’ve no family left to help out.’

‘Where’s your family?’

‘Dead.’

‘What, all of them?’

‘Yes,’ Moses says, baring his palms with a shrug. ‘I still do it, as a hobby though. Let people come to the shop for free, like a museum. Leave the door open and have a cup of tea. Or sometimes I make new pieces but I never show those. Those I just leave places.’

‘Places?’

‘Anywhere. On a bus, in a field, a changing room. I once left a very handsome crow in the bathroom of an ex-lover.’

‘Did she like it?’

‘Parting gift. Never saw her again.’

‘Good for her.’

He snorts, tilting back his head. I stare at the cursive on his jugular, watching Emilia pulse as he swallows.

‘It’s kind of disgusting, don’t you think? Taking bodies from their graves and cutting them open. Preserving things that were meant to rot and then putting them places they’re not supposed to be. Like playing God. Tasteless.’

‘Absolutely,’ he says. ‘Absolutely, I agree. And seeing as I’m confessing, do you want to know something else?’ Moses’ lips curl and shallow dimples appear on his cheeks. In the intensity of his words my body has leaned in. He moves his freaky fingers to toy with my pen, taking hold of the chewed up part that was in my mouth. He taps it, then drops it down. Taps it, drops it down.

‘No,’ I say. ‘I don’t want to know anything else.’

‘You’ll like it more than you expect.’

The pen taps. ‘Still no.’

‘Are you sure?’

I squint. ‘Are you a pervert?’

His laugh erupts, enormous, quaking, cavernous. Footsteps can be heard for a moment upstairs. I find myself praying for the bread-maker.

‘No, no,’ he says. ‘Just lonely. I just like to talk. For me conversations are few and far between. I have many encounters, sure, but never real conversation. So this place is an opportunity to me. Here we are – nothing to do and nothing to see. And of course, it could also be an opportunity to you. I’d like to distract you. Let you think about something other than these men. I hate men.’

‘No thank you, I don’t fraternise with perverts.’

‘You’re not even a little bit curious?’

My notebook remains untouched on the table.

‘No.’

Moses’ writhing lip peels to reveal the scum edge of his teeth.

‘Well, what is it?’

He nods graciously. ‘I will tell you, but you have to be open minded.’ He’s like a child the way he sucks on this situation, the way he anticipates.

‘Moses, it’s getting late. Either tell me this thing or don’t.’

He bites his lip, smiles, opens his mouth, closes it. The kitchen clock ticks slowly. Thirteen minutes past a plum. He leans back, eyes fixed to me.

‘I’m a vampire,’ he says.

That earns a blink.

I wait and wait but he says nothing more. I snort. ‘That’s a weak metaphor.’

‘No, really – I am. I’m a vampire.’

This is a different kind of humour than before. Darker, uglier, uneasy. He puts my pen into his mouth.

‘Dirty Old Man,’ I say. ‘Pervert.’

‘I’m not a pervert,’ he insists, slamming my pen down. He almost knocks over his teacup and it clatters on its saucer. He tries to still it with his hands, gets tea-drops on his fingers. He quietens. ‘I can prove it to you,’ he murmurs. ‘Look.’

He uses his fingers to pull back the lips of his long mouth, so he may properly bare his teeth. I am pressed hard into the back of my chair, but I cannot stop myself from peering into his mouth. His teeth are smoke-stained a pale dirty blue, but sure enough, two perfectly pointed incisors sit like milk-jewels at the front of his mouth.

‘That’s just teeth,’ I say, but I don’t sound certain. My gut feels tight like I might need to shit again, but my neck hairs are doing something weird – tingling in alarm I think, yet I don’t do anything about it. My eyes remain upon his mouth.

He huffs and drops his lips, looking about the kitchen with exasperation. ‘Here,’ he says. ‘Pass me that clove of garlic.’ He points to a little bowl by the stove. A few cloves sit desecrated by the shell of their mother bulb. If I touch them my fingers will smell, I think, before landing on the bafflement of his command.

‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’

‘Pass it to me.’

‘Why?’

‘I will prove myself to you.’

Confused and flustered, I stand from my chair. Its legs collide harshly with the floor. I walk to the little bowl, pick up the garlic and move to give it to Moses, but he shakes his head and opens one broad flat palm.

‘Pull off the skin and drop it into my hand.’

I stare at him. ‘No.’

He ducks his head as though he is being calm and reasonable. ‘I want to show you what it does when it touches me.’

‘Moses, this is exhausting.’

‘Just do it.’

I stand considering for a long moment before finally digging my thumbnail into the clove and pulling off its paper skin. I approach him hesitantly even though the possibility of assault does not feel distant. Closer still, the possibility of humiliation. Recently, it feels I am always barrelling towards these things.

Reaching out, I hold the peeled clove of garlic just above his open hand. Moses’s elasticated body turns suddenly mountain still.

For a moment there is no sound in the kitchen.

He looks up, confused. ‘No?’

‘I believe you.’ I close my fist over the garlic clove so that it is nestled safely in the clammy part of my palm.

Moses stares at me. His nostrils flare and I can see dark hair inside. ‘You believe me?’ he says, as if I’m ruining the perfect joke. At once his body both elates and deflates. It seems I’ve given him an interesting answer, yet the careful arranging of his secret has collapsed like a house of cards.

‘Well?’ he says.

I breathe, thin and slow and careful, focussed on not allowing any reaction to spasm in the muscles of my face. ‘Are you going to kill me? Stuff me? Eat me?’

Humour ripples across his face but his mouth falls serious. He shakes his head once. ‘No.’

‘Then do you mind if I go to bed?’

His cheeks perk and drop with uncertainty. He waves one hand. ‘No, no. Go.’

I nod and grab my notebook, the pen that has been in both our mouths. I slip past him but pause at the door.

‘Goodnight then, Moses.’

‘Goodnight, Noelle.’

You know, I almost did drop the clove for him. It isn’t until I’m in the bathroom, nervously shitting, that the memory comes loose and I can see why I did not.

One time, Lomie and I were smoking at the kitchen window, leaning out over drunken Edinburgh and talking for days. She was my half-flatmate, someone who was around for a while, someone who was also separate. Lomie said something to me. She was angry, though not at me. We were always angry about something but we were angry about it together. She was the one who led our plight because she was comfortable speaking passionately and without filter. Speaking at all. As always, it was my turn to be the audience to her anger, a position I had come to cherish. I was nodding and listening to her vent, taking in almost nothing, too hypnotised by the Lomiean flicks of her seethes and sentences. I’d listened to her talk so much and so often at that time that, as a result, many of her words have fused together in my memory until I can remember no meaning at all. But I suppose one strange part, one small observation, must have hidden itself somewhere. Gotten lodged between the squishy folds like a splinter and remained unrevealed until now.

I understand you, she said to me, as I held the garlic clove above his palm. Sometimes the only thing you’ve got is silence. Sometimes the only option you have is choosing not to know.

It’s the last I’ll think of her for a while.

Lake Mirror

Miss Fraser wakes me from a fitful sleep with the frantic dinging of her breakfast bell. It is so early that the sky is shrouded deep blue as though we have bypassed the day completely and are bowing again toward night. I come out into the hallway bleary, too sleep-logged to question her imposition on my unconsciousness.

She tuts at me in her fuchsia dressing gown. ‘That was my third round of ringing, dear. I was beginning to think you were dead.’

In the kitchen Moses sits upright with another cup of tea, biting his nails. He smiles at me as I enter, eyes immediately trying to root through mine. I take a seat at the opposite side of the table and Miss Fraser bustles in behind me. She begins chopping onions with a large meat cleaver.

‘What are you making?’ I ask her.

‘Omelettes!’ she exclaims, no less exuberant in the morning than at night. ‘Very French. Plenty of protein! Toughen you two up a bit.’

‘Lovely,’ I say. ‘Can I have some garlic in mine please?’

Moses snorts.

Miss Fraser prepares the omelettes and Moses thumbs through another beaten paperback, a Charles Bukowski novel. I’ve read it before. It’s got a rape scene in it that maybe is supposed to be funny. I figured if I couldn’t tell then it probably wasn’t, but by the time I’d made that decision I had more or less finished it anyway. Moses is a good way through the book. I wonder if he slept at all. He doesn’t turn the page for a long time, instead his eyes flick up to peck at me. Quick furtive glances I can feel like heat on my face.