5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

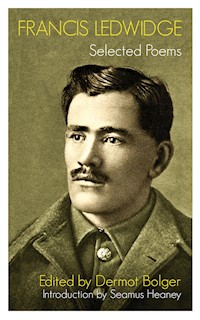

Born in poverty in Slane, County Meath, Ledwidge worked as a farm hand, copper miner and road labourer. In his twenties he would become a rising star in the Irish literary scene, although he lived only to see one collection of his verse in print, receiving his author's copy while freezing and on starvation rations in Serbia. Although a staunch Irish Nationalist, he chose to fight in the First World War, where he died just short of his thirtieth birthday – in the inhuman nightmare that was the Third Battle of Ypres. This selection of Francis Ledwidge's poems, edited by Dermot Bolger, celebrates a remarkably gifted poet who, one hundred years after his tragic death in Ypres, is perhaps best known for the poetic brilliance of much of his work as well as the circumstances of his death. Introduced by Seamus Heaney and with an extended afterword by Dermot Bolger, this volume captures the depth and lyric grace of Ledwidge's finest poems and conjures a moving portrait of an eventful life cut tragically short.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Francis Ledwidge

Francis Ledwidge

Selected Poems

Edited and with an Afterword by Dermot Bolger

Introduction by Seamus Heaney

FRANCIS LEDWIDGE: SELECTED POEMS Published in 2017 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Office Park

Stillorgan

County Dublin

Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Selection and Afterword Copyright © Dermot Bolger, 2007, 2017

Introduction Copyright © The Literary Estate of Seamus Heaney, 2007, 2017

The Authors assert their moral rights in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-593-6 Epub ISBN: 978-1-84840-594-3 Mobi ISBN: 978-1-84840-595-0

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon), 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2, Ireland.

CONTENTS

Editor’s Note by Dermot Bolger

Introduction by Seamus Heaney

In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge by Seamus Heaney

A Little Boy in the Morning

Songs of the Fields

Behind the Closed Eye

A Twilight in Middle March

Desire in Spring

May Morning

June

August

The Hills

The Wife of Llew

To a Linnet in a Cage

Thoughts at the Trysting Stile

Before the Tears

All-Hallows Eve

A Fear

Before the War of Cooley

God’s Remembrance

The Vision on the Brink

Waiting

Songs of Peace

The Place

May

To Eilish of the Fair Hair

The Gardener

Lullaby

The Home-Coming of the Sheep

My Mother

To One Dead

Skreen Cross Roads

Lament for Thomas MacDonagh

The Blackbirds

Fate

At Currabwee

Last Songs

At Evening

To a Sparrow

Had I a Golden Pound

After Court Martial

The Cobbler of Sari Gueul

Home

The Dead Kings

To One Who Comes Now and Then

Soliloquy

With Flowers

A Soldier’s Grave

Afterword

Milestone to Monument:

A Personal Journey in Search of Francis Ledwidge by Dermot Bolger

EDITOR’S NOTE

Dermot Bolger

This volume has its origins in a lifelong ambition of mine to see into print a Selected Poems by Francis Ledwidge. This selection first appeared in 1992. It was republished with additional material under the title The Ledwidge Treasury in 2007 to mark the 90th anniversary of the poet’s death. This new edition, which reinstates the original 1992 title of Selected Poems, is now being released as part of a series of commemorative events to mark the centenary of Francis Ledwidge’s death. In his own lifetime, Ledwidge only saw one small volume of his poetry in print and was awaiting the appearance of his second, Songs of Peace, when he was killed by a stray shell at Ypres on 31 July 1917, while – in a cruel irony – working at the same job he had spent so much of his early manhood in Meath doing – building a road through mud. Songs of Peace, which appeared three months later, was followed by Last Songs, edited, like the first two, by Lord Dunsany, and all three collections were quickly put together to form a Complete Poems, which went through a number of editions between then and 1955.

However, this Complete Poems left out a great deal of material. Alice Curtayne compiled a much extended Complete Poems in 1974, which served to reveal the full achievement of Francis Ledwidge as a poet. However, it forsook any chronological approach to the poems and instead grouped them under thematic headings like Birds and Blossoms, Flights of Fancy and Months and Seasons.

In making this selection of the best of his work, I have regrouped the poems back into their original three volumes and added in a number of poems uncovered by Alice Curtayne (marked by the initials C.P. for Complete Poems) where I feel they roughly belong in time. In Songs of Peace, either Ledwidge or Dunsany had grouped the poems according to where they were written and, where available, I have added these locations and dates in brackets.

One poem which is out of sequence is ‘A Little Boy in the Morning’, a delicate elegy for a local boy, Jack Tiernan, whom he used to meet herding cattle for local farmers at dawn – a job which he himself had once done. Death was something Ledwidge understood. On one of Ledwidge’s last trips home from the war he heard about the boy’s death from TB. It is typical that from such a tragedy Ledwidge minted a poem of freshness and light. As I say in my afterword, if the poem ‘Lament for Thomas MacDonagh’ can also be read as a lament for the adult Ledwidge himself, then his poem for Jack Tiernan might be an epitaph for the younger Ledwidge, rushing with his brother after school to join their mother stooping at work in the frosty dusk of other men’s fields, walking home together through the dark, already with the gift of poetry forming in his head.

INTRODUCTION

Seamus Heaney

It was appropriate that the excellent biography of Francis Ledwidge which appeared in 1972 should have been written by Alice Curtayne, a scholar noted more for her works on religious subjects than for her literary studies. Even though Ms Curtayne did once publish a study of Dante, her name, like Ledwidge’s, evokes a certain nostalgia for those decades when this poet was appropriated and gratefully cherished as the guarantor of an Ireland domesticated, pious and demure; his poems used to be a safe bet for the convent library and the school prize, a charm against all that modernity which threatened the traditional values of a country battening down for independence. But Ledwidge’s fate had been more complex and more modern than that. He very deliberately chose not to bury his head in local sand and, as a consequence, faced the choices and moral challenges of his times with solitude, honesty and rare courage. This integrity, and its ultimately gratifying effects upon his poetry, should command the renewed interest and respect of Irish people at the present time: Ledwidge lived through a similar period of historical transition when political, cultural and constitutional crises put into question values which had previously appeared as ratified and immutable as the contours of the land itself.

A lot of Irish people can still quote at least one line of his poetry. ‘He shall not hear the bittern cry,’ they say, and then memory falters until the final image of ‘Lament for Thomas MacDonagh’ comes back, and they make a stab at something about the Dark Cow ‘lifting her horn in pleasant meads’. For many of these people, Ledwidge vaguely belongs to the moment of 1916 and his note plays in with poems like Joseph Mary Plunkett’s ‘I see his blood upon the rose’ and Padraig Pearse’s ‘Mise Eire’, so that he is conceived of as somebody who ‘sang to sweeten Ireland’s wrong’. But for others, the abiding impression left by this poet is one of political ambivalence. For these people, the salient factor is his enlistment in the British Army in 1914 and his being in its ranks during the Easter Rising, in the uniform of those who executed, among others, Thomas MacDonagh. The blame for this inconvenient shoneenism, however, is then laid at the aristocratic feet of Lord Dunsany, Ledwidge’s most helpful mentor, literary agent and patron, so that in this scenario the poet shows up as a naïve patriot betrayed by the scheming Unionist peer into an act that went against his truest dispositions and convictions.

As Alice Curtayne’s biography (to which I am here greatly indebted) makes clear, neither of these versions will do. To see him as the uncomplicated voice of romantic nationalism misrepresents the agonized consciousness which held in balance and ultimately decided between the command to act upon the dictates of a morality he took to be both objective and universally applicable, and the desire to keep faith with a politically resistant and particularly contentious Irish line. To see him as the dupe of a socially superior and politically insidious West British toff is to underrate his intelligence, his independence and the consciously fatal nature of his decision to enlist. For Ledwidge was no wilting flower; as James Stephens wrote of him:

I met him twice and then only for a few minutes. He is what we call here ‘a lump of a lad’ and he was panoplied in all the protective devices, or disguises, which a countryman puts on when he meets a man of the town!

This is the Ledwidge who is now commemorated by a plaque placed first on the bridge over the River Boyne at Slane, and then on the restored labourer’s cottage outside the village where he was born on 19 August 1887, the second youngest in a surviving family of four brothers and three sisters. That the plaque appeared on the bridge first rather than the house has a certain appropriateness also, since the bridge, like the poet, was actually and symbolically placed between two Irelands.

Upstream, then and now, were situated several pleasant and potent reminders of an Anglicized, assimilated country: the Marquis of Conyngham’s parkland sweeping down to the artfully wooded banks of the river, the waters of the river itself pouring their delicious sheen over the weir; Slane Castle and the big house at Beauparc; the canal and the towpath – here was an Irish landscape in which a young man like Ledwidge would be as likely to play cricket (he did) as Gaelic football (which he did also). The whole scene was as composed and historical as a topographical print, and possessed the tranquil allure of the established order of nineteenth-century, post-union Ireland. Downstream, however, there were historical and prehistorical reminders of a different sort which operated as a strong counter-establishment influence in the young Ledwidge’s mind. The Boyne battlefield, the megalithic tombs at Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth, the Celtic burying ground at Rosnaree – these things were beginning to be construed as part of the mystical body of an Irish culture which had suffered mutilation and was in need of restoration. Ledwidge would also have known about local associations with St Patrick, Cormac Mac Airt, Aengus the love god and many other legendary figures; and not far away was the Hill of Tara, where his mother filled his mind with the usual lore:

That old mill, built on the site of the first cornmill ever erected in Ireland, used to belong to my father’s people when everybody had their own and these broad acres and leopard-coloured woods, almost as far as Kilcairne, all these were ours one time.