71,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

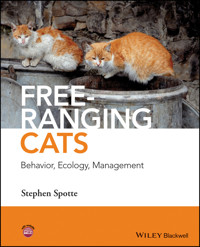

Feral and stray domestic cats occupy many different habitats. They can resist dehydration for months by relying exclusively on the tissue water of their prey allowing them to colonize remote deserts and other inhospitable places. They thrive and reproduce in humid equatorial rainforests and windswept subantarctic islands. In many areas of the world feral cats have driven some species of birds and mammals to extinction and others to the edge, becoming a huge conservation concern. With the control of feral and stray cats now a top conservation priority, biologists are intensifying efforts to understand cat behaviour, reproductive biology, use of space, intraspecies interaction, dietary requirements, prey preferences, and vulnerability to different management strategies.

This book provides the most comprehensive review yet published on the behavior, ecology and management of free-ranging domestic cats, whether they be owned, stray, or feral. It reviews management methods and their progress, and questions several widely accepted views of free-ranging cats, notably that they live within dominance hierarchies and are highly social.

Insightful and objective, this book includes:

- a functional approach, emphasizing sensory biology, reproductive physiology, nutrition, and space

partitioning; - clear treatment of how free-ranging cats should be managed;

- extensive critical interpretation of the world's existing literature;

- results of studies of cats in laboratories under controlled conditions, with data that can also be

applied to pet cats.

Free-ranging Cats: Behavior, Ecology, Management is valuable to ecologists, conservation scientists, animal behaviorists, wildlife nutritionists, wildlife biologists, research and wildlife veterinarians, clinical veterinarians, mammalogists, and park and game reserve planners and administrators.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 805

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

Abbreviations and symbols

About the companion website

Chapter 1: Dominance

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Dominance defined

1.3 Dominance status and dominance hierarchies

1.4 Dominance–submissive behavior

1.5 Dominance in free-ranging cats

Chapter 2: Space

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Space defined

2.3 Diel activity

2.4 Dispersal

2.5 Inbreeding avoidance

2.6 Home-range boundaries

2.7 Determinants of home-range size

2.8 Habitat selection

2.9 Scent-marking

Chapter 3: Interaction

3.1 Introduction

3.2 The asocial domestic cat

3.3 Solitary or social?

3.4 Cooperative or not?

3.5 The kinship dilemma

3.6 What it takes to be social

Chapter 4: Reproduction

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Female reproductive biology

4.3 Male reproductive biology

4.4 The cat mating system: promiscuity or polygyny?

4.5 Female mating behavior

4.6 Male mating behavior

4.7 Female choice

Chapter 5: Development

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Intrauterine development

5.3 Dens

5.4 Parturition

5.5 Early maturation

5.6 Nursing

5.7 Weaning

5.8 Survival

5.9 Effect of early weaning and separation

5.10 Early predatory behavior

Chapter 6: Emulative learning and play

6.1 Introduction

6.2 Emulative learning

6.3 Play

6.4 Ontogenesis of play

6.5 What is play?

Chapter 7: Nutrition

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Proximate composition

7.3 Proteins

7.6 Fiber

7.7 Vitamins

Chapter 8: Water balance and energy

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Water balance

8.3 Energy

8.4 Energy needs of free-ranging cats

8.5 Energy costs of pregnancy and lactation

8.6 Obesity

Chapter 9: Foraging

9.1 Introduction

9.2 Cats as predators

9.3 Scavenging

9.4 When cats hunt

9.5 Food intake of feral cats

9.6 How cats detect prey

9.7 How cats hunt

9.8 What cats hunt

9.9 Prey selection

9.10 The motivation to hunt

Chapter 10: Management

10.1 Introduction

10.2 Effect of free-ranging cats on wildlife

10.3 Trap–neuter–release (TNR)

10.4 Biological control

10.5 Poisoning and other eradication methods

10.6 Integrated control

10.7 Preparation for eradication programs

10.8 “Secondary” prey management

References

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

xi

xii

xiii

xvii

xix

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Preface

Begin Reading

List of Illustrations

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.3

Figure 1.4

Figure 1.5

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.2

Figure 2.3

Figure 2.4

Figure 2.5

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.2

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.2

Figure 4.3

Figure 4.4

Figure 4.5

Figure 4.6

Figure 4.7

Figure 4.8

Figure 4.9

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.11

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.9

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.2

Figure 6.3

Figure 6.4

Figure 6.5

Figure 6.6

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.2

Figure 7.3

Figure 7.4

Figure 8.1

Figure 8.2

Figure 8.3

Figure 8.4

Figure 8.5

Figure 8.6

Figure 8.7

Figure 8.8

Figure 8.9

Figure 9.1

Figure 9.2

Figure 9.3

Figure 9.4

Figure 9.5

Figure 9.6

Figure 9.7

Figure 9.8

Figure 9.9

Figure 10.1

Figure 10.2

Figure 10.3

Figure 10.4

Figure 10.5

Figure 10.6

Figure 10.7

Figure 10.8

Figure 10.9

Figure 10.10

List of Tables

Table 2.1

Table 4.1

Table 4.2

Table 5.1

Table 5.2

Table 6.1

Table 7.1

Table 7.2

Table 7.3

Table 7.4

Table 7.5

Table 7.6

Table 8.1

Table 8.2

Table 8.3

Table 9.1

Table 9.2

Free-ranging Cats

Behavior, Ecology, Management

Stephen Spotte

This edition first published 2014 © 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Registered office: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19

8SQ, UK

Editorial offices: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spotte, Stephen.

Free-ranging cats : behavior, ecology, management / Stephen Spotte.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-118-88401-0 (cloth)

1. Feral cats. I. Title.

SF450.S66 2014

636.8–dc23

2014013795

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Cover image: Two Stray Cats on Garbage Bins. © Vicspacewalker | Dreamstime.com

1 2014

To Puddy, Tigger, Miss Sniff, Wilkins, Beavis, and Jinx

You enriched my life

Preface

The dog is humankind's obsequious, slavering companion ever sensitive to its master's moods and desires. The cat is ambiguous, irresolute, indifferent to its owner, if indeed any human who co-habits with a cat can be called that. Many of my cats have been memorable, perhaps none moreso than Miss Sniff, who adopted me when I lived on a Connecticut farm. It happened like this. One night in late autumn I heard a noise outside and opened the door. In walked an ugly, leggy, calico cat. She had the triangular head and blank stare of a praying mantis, and her nose was in the air mimicking a sort of feline royalty. With startling arrogance she jumped onto the couch and made one end of it hers. And so I named her Miss Sniff.

For months my barn had been plagued by rats. Their excavations were everywhere, around the perimeter of the building and even deep into the clay floors of the horse stalls. Nothing I tried could eradicate them. They ignored traps, snickered at poisoned grain, shouldered aside the barn cats and ate the food from their bowl. Some, bored with the furtive life, lounged brazenly outside their burrows in full sunlight.

That first night I fed Miss Sniff and eased her out the door. She greeted me the next morning with a freshly killed rat, a large shaggy beast of frightening proportions. Female cats without kittens to raise often bring their prey home, laying it out in a convenient place and giving little churring calls to their humans. Paul Leyhausen (1979: 88–89) wrote: “The important thing for the cat is … not the praise but the fact that the human serving as ‘deputy kitten’ actually goes to the prey it has brought home, just as a kitten thus coaxed does.” I have no idea if Leyhausen's interpretation is true, but I nonetheless congratulated Miss Sniff, gave her a pat, and every morning thereafter she presented me with a dead rat. Within a few weeks she had caught them all. In retrospect I realize how mere praise was a paltry reward, and to express proper gratitude I should have sat down on the porch steps and eaten the rats in front of her. At least one or two simply to be polite.

The common cat is the most widespread terrestrial carnivoran on Earth, occupying locations from 55°N to 52°S and climatic zones ranging from subantarctic islands to deserts and equatorial rainforests (Konecny 1987a). This is possible because few carnivorans except possibly the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) can match its ecological flexibility and the capacity to find food and reproduce almost anywhere. As further evidence of protean adaptability, the cat has become the most common mammalian pet with an estimated 142 million having owners worldwide (Turner and Bateson 2000). Domestic cats are now the most popular house pet in the United States (Adkins 1997). According to the Pet Food Institute (2012) the estimated number of pet cats in the United States is >84 million, well in excess of the number of pet dogs (>75 million). Castillo and Clarke (2003) set the total number of US cats at 100 million, including those without owners.

At the same time, free-ranging cats—many of them house pets—exact a devastating toll on wildlife around the world. May (1988) estimated that there were ∼6 million free-ranging house cats in Britain. Although well fed, they killed an average of 14 prey items each per day, which extrapolates to ∼100 million birds and small mammals annually. In the final chapter I present evidence that killing unowned cats is the only sensible method of controlling their depredation on wildlife. Eradication programs are unpopular with those bent on saving cats at all costs. However, the pressure placed on wild creatures should be alleviated whenever possible, and subtracting alien predators from terrestrial ecosystems is one way of reducing the carnage.

The underlying thesis throughout is that effective management of free-ranging cats is best achieved if based on understanding their behavior, biology, and ecology. In this respect I take issue with experts who claim cats to be social, occupy rank-order positions in dominance hierarchies, disperse under pressure from inbreeding avoidance, are territorial, have a polygynous mating system, and live in functioning kinship groups in which cooperation is common. The data do not support any of these positions, and failure to discard them stands in the way of real progress toward our understanding of why cats behave as they do. More important, casual disregard of the cat's reproductive biology and unusual nutritional requirements has hampered the search for novel methods of population control, limiting current choices to biological agents (e.g. feline panleucopenia virus) and nonselective poisons, augmented by trapping and shooting.

We should take a closer look at the domestic cat for other reasons too. The family Felidae is thought to contain ∼40 species (Wildt et al. (1998: 505, Table 1), and all except the domestic cat are under threat of extinction (Bristol-Gould and Woodruff 2006, França and Godinho 2003, Goodrowe et al. 1989, Neubauer et al. 2004, Nowell and Jackson 1996, Pukazhenthi et al. 2001). The ordinary cat has therefore become a model for conserving other felids through study of its reproductive and sensory biology, genetics, behavior, use of habitat, and nutritional needs.

Cat biology is highly context-dependent. Laboratory studies have taught us much, and knowledge of free-ranging cats is paltry in comparison. My discussion focuses on the latter, but where lacunas exist I fill them with what we know from cats kept in confinement and presume that the differences are not too great. This is a reasonable approach, at least from a physiological standpoint. Cat genetics are well conserved (Plantinga et al. 2011), meaning the metabolic adaptations of cats are not likely to vary whether they occupy a laboratory cage, alley, or sofa cushion. Endocrine factors driving reproduction, for example, are difficult to monitor except in a lab, but differences compared with free-ranging cats are matters of degree, not kind.

I consider free-ranging cats classifiable into three categories: feral, stray, and house. Feral cats survive and reproduce without human assistance and often despite human interference (Berkeley 1982). Stray cats occupy urban, suburban, and rural areas where humans assist indirectly by making garbage available to scavenge and by offering shelter underneath houses and in abandoned buildings. Garbage represents a concentrated food source and also attracts rodents and birds, still other sources of food. Although strays are sometimes fed by sympathetic people, they are less likely to be offered shelter and veterinary care. Free-ranging house cats are those allowed outdoors unsupervised by their owners, who provide consistent shelter, food, and usually veterinary care.

Never take for granted a cat's understated ability to influence our own behavior. During an election year a while back in the village of Talkeetna, Alaska, the populace grew unhappy with its mayoral candidates. Someone started a write-in campaign for a yellow tabby named Stubbs, who hung out in the General Store. Stubbs won, and is now the mayor. Like politicians everywhere he spends much of his time asleep on the job, refusing to let the responsibilities of elected office become a distraction.

Stephen SpotteLongboat Key, Florida

For cats, indeed, are for cats. And should you wish to learn about cats, only a cat can tell you.

Sōseki Natsume, I Am a Cat

Abbreviations and symbols

mean

µmol

micromole

a

scaling constant (power law)

ATP

adenosine triphosphate

BCFA

branch-chained fatty acid

BMR

basal metabolic rate

BSA

body surface area

cd

candela

CL

corpus (corpora) lutea

CM

center of mass

CSF

contrast sensitivity function

d

day(s)

dB

decibel(s)

DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

DM

dry matter

DMI

density-mediated interaction

E

energy

EAA

essential amino acid

EFA

essential fatty acid

EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

EUNL

endogenous urinary nitrogen loss

FC

food consumption

FPL

feline panleucopenia

FUNL

fasting urinary nitrogen loss

g

gram(s)

GnRH

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

ha

hectare(s)

k

scaling exponent (power law)

kcal

kilocalorie(s)

kg

kilogram(s)

kHz

kilohertz

kJ

kilojoule(s)

L

liter(s)

LH

luteinizing hormone

M

body mass

MAF

minimum auditory field

mg

milligram(s)

min

minute(s)

mmol

millimole(s)

ms

millisecond(s)

MUP

major urinary protein

NFE

nitrogen-free extract

ONL

obligatory nitrogen loss

PAPP

p

-aminopropiophenone

PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

RDH

resource dispersion hypothesis

s

second(s)

SCFA

short-chained fatty acid

SD (or σ)

standard deviation of the mean

SEM

standard error of the mean

TMI

trait-mediated interaction

TRSN

tecto-reticulo-spinal tract

TS

total solids

UV

ultraviolet

VNO

vomeronasal organ

VR

vomeronasal receptor

W

watt(s)

y

year(s)

About the companion website

This book is accompanied by a companion website:

www.wiley.com/go/spotte/cats

The website includes:

Powerpoints of all figures from the book for downloading

PDFs of tables from the book and online appendices

Chapter 1Dominance

1.1 Introduction

The concept of dominance appears often in the animal behavior literature. When defined at all its meaning and usage are often inconsistent, making any comparison of results among experiments ambiguous. How we think of dominance necessarily influences findings obtained by observation (Syme 1974). Perhaps because domestic cats are asocial (Chapter 3), their expressions of dominance seem strongly situation-specific (Bernstein 1981, Richards 1974, Tufto et al. 1998) rather than manifestations of a societal mandate, making dominance–subordinate relationships less predictive of reproductive success and other fitness measures.

My objectives here are to define and describe dominance behavior and try to evaluate its relevance in the lives of free-ranging cats. Much experimental work on dominance and subordination in laboratory settings has only peripheral application to cats living outdoors. Consequently, I seriously doubt that watching cats crowded together in cages yields anything except measures of aberrant behavior, not at all unusual when circumstances keep animals from dispersing (Spotte 2012: 221–227).

The dominance concept has done little to enlighten our understanding of how free-ranging cats interact, its utility seemingly more applicable to animals demonstrating true sociality. As I hope to make clear, agonistic interactions between free-ranging cats are mostly fleeting, situational, and the consequences seldom permanent because neither participant has much to gain or lose. Baron et al. (1957) and Leyhausen (1965) used relative dominance when referring to how vigorously an individual dominates subordinates, meaning that some cats are more dominant than others in relative terms, perhaps by not allowing subordinates to usurp them even momentarily at the food bowl if a subordinate growls or by refusing to share food. That measurements of relative dominance, situational dominance, or dominance by any category have utility in assessing the interactions of free-ranging cats is doubtful. Food is not highly motivating. Small groups of cats, whether captive (Mugford 1977), feral (Apps 1986b), or stray (Izawa et al. 1982), seldom fight over food or anything else, raising the question of whether the “dominance” observed during arena tests and based on food motivation is not mostly an artifact of experimental conditions. As Mugford (1977: 33) wrote of laboratory cats fed ad libitum, “Less than 1% of total available time was accounted for by feeding, so it would be difficult for any single dominant animal to retain exclusive possession of the food pan. …”

1.2 Dominance defined

The most useful definition of any scientific term consists of a simple falsifiable statement devised to reveal some causal effect in nature beyond mere description and data analysis. Flannelly and Blanchard (1981: 440) made clear that “dominance is not an entity, but an attempt to describe in a single word the complex interactions of neurology and behavior.” This is important to remember and useful conceptually, although difficult to wrestle into falsifiable hypotheses if the only available method of testing involves observation without manipulation of the subjects or conditions.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!