13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

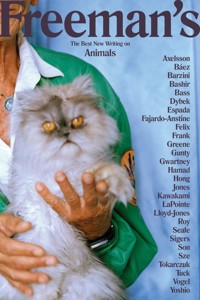

Over a century ago, Rilke went to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, where he watched a pair of flamingos. A flock of other birds screeched by, and, as he describes in a poem, the great red-pink birds sauntered on, unphased, then 'stretched amazed and singly march into the imaginary.' This encounter - so strange, so typical of flamingos with their fabulous posture - is also still typical of how we interact with animals. Even as our actions threaten their very survival, they are still symbolic, captivating and captive, caught in a drama of our framing. This issue of Freeman's tells the story of that interaction, its costs, its tendernesses, the mythological flex of it. From lovers in a Chiara Barzini story, falling apart as a group of wild boars roams in their Roman neighbourhood, to the soppen emergency birth of a cow on a Wales farm, stunningly described by Cynan Jones, no one has the moral high ground here. Nor is this a piece of mourning. There's wonder, humour, rage and relief, too. Featuring pigeons, calves, stray dogs, mascots, stolen cats, and bears, to the captive, tortured animals who make up our food supply, powerfully described in Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk's essay, this wide-ranging issue of Freeman's will stimulate discussion and dreams alike.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Freeman’s

Animals

Previous IssuesFreeman’s: ArrivalFreeman’s: FamilyFreeman’s: HomeFreeman’s: The Future of New WritingFreeman’s: PowerFreeman’s: CaliforniaFreeman’s: LoveFreeman’s: Change

First published in the United States of America in 2022 by Grove Atlantic

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of

Grove Atlantic

Copyright © 2022 by John Freeman

Managing Editor: Julia Berner-Tobin

Assistant Editor: Emily Burns

Copy Editor: Kirsten Giebutowski

All pieces are copyright © 2022 by the author of the piece. Permission to use any individual piece must be obtained from its author.

“The Cat Thief” by Son Bo-mi was originally published in Korean in Maenhaeteunui Banditburi (The Fireflies of Manhattan) by Maum Sanchaek in 2019.

“IV - VII” from Aednan by Linnea Axelsson and translated into English by Saskia Vogel. Available in August 2023 from Alfred A. Knopf.

“The Masks of Animals” by Olga Tokarczuk was published in Polish in Krytyka Polityczna, nr 15, 2008.

The moral right of the authors contained herein to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 424 4

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 871 6

Printed in Great Britain

Contents

Introduction

John Freeman

Six Shorts

Anuradha Roy

Debra Gwartney

Mieko Kawakami

Matthew Gavin Frank

A. Kendra Greene

Son Bo-mi

Cow

Cynan Jones

Ædnan

Linnea Axelsson

The Masks of Animals

Olga Tokarczuk

Baroque, Montana

Rick Bass

In Some Thousand Years

Camonghne Felix

Let the Memory Rise

Lily Tuck

Here’s the Thing:

Samiya Bashir

First Salmon Ceremony

Sasha taqwšəblu LaPointe

The Art of Breathing

Stuart Dybek

Star

Kali Fajardo-Anstine

Oxbow Lakes

Arthur Sze

Gigi and the White Rabbit

Ameer Hamad

The Boar

Chiara Barzini

Love Song of the Moa

Martín Espada

Lucky Land

Shanteka Sigers

Yaguareté White

Diego Báez

On Jawless Fish

Tess Gunty

Contributor Notes

About the Editor

Introduction

JOHN FREEMAN

Like almost everyone I’ve come to love, she turned up as if from nowhere. A door in the maze of fate flapped open and through it Martha materialized. 105 pounds of silver-haired, cheese-eating, grumpy perfection—a Weimaraner, mostly, but probably part pit bull too. She looked like a museum gargoyle or a ghost on the lam. Her past was a swirling pot of Dickensian vapors. Someone left her in the rain. A warring couple came to blows, and she escaped. She’d been starved. Cruel men trained their dogs on her to fight. None of this was apparent upon meeting her. Martha simply showed up on my mother-in-law’s couch, a new adoptee in a home fond of hard-luck cases, sporting that ducking self-consciousness all dogs wear when they’ve been hit before and are unsure whether this new life is real or a dream.

She adapted quickly. Soon enough the couch was hers, and the spot next to it, where she’d curl up when she wanted to be close, but not bothered. Within months, she tithed all meals, especially toast, and a failure to acknowledge her rights was often remarked upon. I’ve known many dogs and all of them have communicated, but Martha came closest to speaking. I don’t mean her barking sounded like words, but she could pattern out a very clear message, as if her foot-tap (hello) and blink rate (excuse me, excuse me, ready for toast now) and eye contact and eyebrow movement (seriously? you’re not going to share that with me?) and bark (I’m standing right here!) was the clearest iteration of messaging I’ve ever received from an animal. Give that to me, now, please, put it where toast belongs in my face, thank you Jesus, faster next time is there more?

She was impatient, tetchy, like the house was a train station and she was both its clock and its conductor, trying to keep everything running on time. For almost five years, most of my mornings started around 7:30 or 8. We’d bang into my mother-in-law’s tall London house. At the sound of the door, a drumbeat of dog-feet would begin at the top of the house and cascade downward. Have I said she was a bit chunky? Down the thumping rolled, growing louder and more raucous, until it was like a rock and roll drummer on an overlong solo. Just when you began to expect not one dog but ten, she’d hustle round the corner at the foot of the stairs, just her, grey ears flapping, flashing her tiny, lethally sharp teeth, head turning left, right, left.

She actually smiled. She began each day with a big, frankly very odd cockeyed grin. I think she was mimicking what she saw us do when we were happy, flashing her teeth, saying hello, hello. If you didn’t know her you’d think she was snarling. Then she’d hustle us into the car, circling our legs to herd us, observing our route to the common as we drove off, barking if we stopped in traffic or took a wrong turn, positively squealing if the ride took more than five minutes. Upon arrival she’d explode out the back gate of our wagon, and I’d load up the thrower and she’d sprint after the flung ball like a racehorse, actually chewing up bits of turf with the force of her propulsion, a softer drum-beat now as her feet traveled across grass. Her face upon return an expression of unmitigated triumph.

* * *

Like so many of us, I spent the past three years in the pandemic with an animal. With several, in fact, but in Martha’s case, developing a relationship I think it’s absurd to call by any name but love. What do you call a being whose body gives you comfort? Who doesn’t need words to communicate? Who delivers and receives with acute awareness of these acts? Who has a personality? Who counts? Who makes judgments about people? Who wears coats? Who has moments of vanity? Who dreams? Who is frightened? Who comforts others when they’re frightened? Who mourns? Who feels jealousy? Who feels pain? Who worries about the future? Who enjoys pasta? Who likes the rain? Who tries to get you to look at beautiful things? Yes, Martha often did this: she’d come get me and take me outside to smell something. Or, given my imperfect understanding of her mind and heart, that’s what I think was happening.

As with any compact, be it with a friend or a lover or with God, not knowing made the relationship more powerful. You know nothing really important, if there’s no risk to the heart. If you glean without risk, what you’ve gained is merely information. Maybe this is why, as a species, humans have done so little to stop destroying the planet we share with millions of other living beings, only a small portion of whom are dogs or cats or other domesticated animals. Perhaps it’s simply information to us—the absolutely clear, undeniable lesson that we’ve pumped far too much carbon into the atmosphere and have jeopardized not just our own future on earth, but that of millions of others species too—because we have lost the ability to conceive of our not knowing as crucial a form of intra-species knowledge. It’s as if we need animals to go on strike, to send letters to the editor, to turn up on CNN. Meanwhile, watch the world leaders at global climate crisis conferences. They don’t know when, or exactly how, the models can’t be trusted, proof there’s more time. As if our bodies aren’t also all vibrating with an epidemic of anxiety.

Animals have never been so meaningful—so freighted with meaning—as they are now, as humans face but don’t face our extinction. And yet, because they are so often glimpsed through the keyhole of our greed, our guilt, our passive-aggressive morbid doom-scrolling curiosity, animals remain simultaneously unseen. Show me yourself suffering, now appease my guilt with your cuteness. What is adorableness in the animal kingdom when it is the thing standing between us and the apocalypse? We can marvel at the long songs of deep sea whales, at feather-light octopi and their seemingly intimate behavior, at birds and their patterns of migration, adapting to dried-up water sources and greater predator threats, but unless you have the luxury of being an extremely well-informed consumer, the very next day, due to the structures of the world’s food supply, it’s quite possible to eat the meat of an animal which has been tortured and either not care, or, just as likely, be too exhausted to do anything about it.

The stakes of this moment in time, our contradictory attitudes about its moral dilemmas, and our always-intense curiosity about the lives of animals have made it an important period to re-narrate our relationship to the animal world. To strip this interaction from the fantasy of purity—as if it’s ever possible to truly know a wild living thing, or to observe it without altering its life—and to accept the messy, imperfect not-knowledge of at least some form of creative regard. Of acknowledgment by virtue of symbolic or actual engagement of shared stakes.

This issue of Freeman’s is dedicated to opening the rich space that exists between us and the earth itself, the place that animals inhabit, where they are at once symbolic and actual, part of culture and part of the food supply, a world in which they inform our everyday lexicons, but remain as far away as a howl in the night. This is not a zoo, but a highly subjective and accidental bestiary filled with animals who come from the imagination and the world itself—passenger pigeons, jaguars, ultra-black Dobermans, just-born lambs, rabbits. Bears. Stray dogs. Giraffes. Reindeer. Sloth. Boars who rustle in the wilderness behind a Roman couple’s disquieted home.

We learn to read by imagining the lives of animals. At some point, around ages ten or eleven, they retreat from the center of our reading life, especially in fiction. What would life feel like if that weren’t the case? Would we have more stories like Cynan Jones’s riveting account of four Welsh farmers struggling to survive a brutal lambing season while one of their cows gives birth? Or maybe animals would feel more like trusted guides or protectors, as in Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s short story about a young woman on the precarious edge of ruin in the pandemic, who needs the strength to make a hard decision. She finds it in the form of a radically unashamed stripper and her Doberman. Or maybe there’d be more exquisitely ironic stories about mascots with racialized characters, like Shanteka Sigers’s “Lucky Land,” in which a man has a shocking face-to-face encounter with a human-sized lemur behind the scenes at a popular amusement park.

Where do the animals we meet go, the ones of our childhood, in the afterlife of memory or culture? In Lily Tuck’s story, a girl’s encounter with a bear spins inside her like a top, a dynamo of portent which is forever turning as her life itself evolves and she ages. Elsewhere, in a moving essay, “First Salmon Ceremony,” Sasha taqwšəblu LaPointe describes her decades-long arc away from the fish she ate heartily in her youth, into veganism, and then back toward salmon in adulthood: a journey which charts her own feelings of shame, curiosity, and finally pride about her native identity.

It takes a force as strong as hate to prize such bonds apart, those between us and animals. A violence of policy, of laws. Linnea Axelsson’s breathtaking novel-in-verse is set in Lapland in the early years of the twentieth century and revolves around a world on the cusp of that rupture, wherein a Sami family migrates its reindeer across tundra, up against barriers only nations could erect. In a world now run by these failing but enshrined idealized identities, what nation do animals belong to, what rights do they have, Olga Tokarczuk asks in her stunning essay. What role do our stories play in adjudicating this complex zone? What other function do these stories serve?

Maybe to help us remember, maybe to not forget? They’re different things. Several pieces in this issue function like eulogies to past times—except, as always, humans are there too, behaving in familiar ways. Matthew Gavin Frank recreates an era when passenger pigeons covered the skies thick as storm clouds, inspiring a frenzy of anxiety and then a mass killing. A. Kendra Greene’s tale sardonically invites us to imagine the life of a sloth frozen still as taxidermy. Wherever animals are held in captivity there’s disquiet, like in Mieko Kawakami’s tale of a girl and a boy meeting in a zoo, the speaker quietly, effectively negged by the boy before the gaze of a lugubrious giraffe.

As always, Kawakami finds a way to turn this passive interaction inside out, the speaker’s stoppered tongue turning giraffe-like in the story’s second half. Ultimately, it sets her free. Perhaps Darwin had it wrong, Rick Bass reminds in his essay, it’s not survival of the fittest, it’s the lucky who adapt and survive. What does luck mean though if it’s not chance, but sometimes a bit stranger? Maybe luck is a question of conception, not simply a happening: as in, if you can imagine the impossible, you can speak your way out of silence. If you can add functions to your very body, you can swim out of danger.

If this is the case, and we as a species are even going to try to fathom a way out of the current catastrophe, we’ll have to embrace better models of survival, Samiya Bashir suggests in her exquisitely burning poem “Here’s the Thing:”, which draws the speaker close to the rat. We’re also going to have to envision deeper ways to conceive what is happening, Debra Gwartney writes in “Blue Dot,” because the fires that have come to our very doorstep once were impossible and now they’re here. She knows this because she’s standing in the cindery rubble of a plot of Oregon woods she shared with her late husband Barry Lopez, contemplating how little the forestry service knows of the world around their destroyed cabin. The birds and beasts which called that parcel of forest their home are equally bereft.

Perhaps in a thousand years, as Camonghne Felix writes in her peacefully bleak poem, the world will recover, and we will be the slip of memory. The scar in the earth of a time weathered, and born. In this sense, to deal with life in a time of terror one needs to practice picturing a world without us, something extremely possible during the pandemic, as Anuradha Roy points out in the opening essay. It’s an essay that tests the morality of this exercise, however, for a world without us is not a fate that affects only humans. One of the first casualties of the pandemic in her part of the Himalayas were stray dogs, no longer fed by humans in parks because the residents of her town couldn’t go out.

Animals, in spite of the stories we are told as children, are not here to rescue us or be rescued by us. That is simply one narrative about them. Perhaps one reason we don’t see animals so much in adult life is because the reality of our dominion is simply too bleak. Animals are stolen like objects, as in Son Bo-mi’s story about a cat, or they’re treated casually like trophies, as in Tess Gunty’s dazzling story set in a twenty-first-century house party that overflows with luxury, and rabbits. Or they’re brutally killed in surrogate ways, as in Chiara Barzini’s terrifying tale about two Roman couples and the sexual games they play to rejuvenate their marriages during midlife doldrums.

What’s scary about these stories is not so much what animals may do to us, but what we do to them. Maybe we’d be kinder were we more in touch with the bird inside us, as Martín Espada is in his poem, or if we listened more acutely, as Arthur Sze does in his, stepping outside into a multitude of song, of living-ness, or if we could imagine what abilities can still be activated within us, as Stuart Dybek does in his searching, watery poem-fable that begins: “A theory on the descent of Man has it / that humankind evolved not from bands of monkeys / in the trees, but from a lost race of aquatic apes.”

Humans have got so much wrong over the years about our fellow travelers on this planet, even on the level of language. Diego Báez writes in a poem that while his family comes from Paraguay, there are no longer jaguars there, as popular myth has it, so life, for him, involves daily sapping of such undetonated falsehoods. In the occupied territories of Palestine, Ameer Hamad sets a tale about what happens when such fantasies of otherness come home to roost. A young boy makes his visiting cousin from America an unwitting accomplice in his mission to bring home a rabbit from the pet store.

An animal is not a toy any more than you and I are, something Martha so often made clear to me when I spoke to her like one. She simply refused to listen. She walked away. And I’d be ashamed that some atavistic part of me had reared up and addressed her in the manner I may have once spoken to a Lego, a stuffed animal, a part of the world that seemed animate to me as a child, but wasn’t. Martha may not have spoken English, but she had the dignity of all living beings, from trees to bees to bears and yes, twelve-year-old Weimaraners. She had her own sense of the world, a powerful juxtaposition, a series of instincts as deep in her as mine were in me.

I wish I had known what she wanted us to do when she got sick. Did she want our medicine? Did she want to die? On this question she was mute, or we couldn’t read the signals. We did in the end what we would have wanted, which was to secure more time, and thanks to a very good vet, she got it. Two months. In a dog’s life, it was a year. A whole cycle of the inner planet, falling in the dark through dreams, night storms, toast crusts. I had never seen her run so fast the day she returned home from the vet and we removed the cone around her neck. She bounded back onto the common and beat lurchers, vizslas, even a fleet-footed dalmatian to her ball. She sniffed the flowers, she visited her two favorite trees, which she seemed to greet by running up to them and stopping abruptly, then standing at attention as all hunting dogs do when they’ve found something important. She stood there those last few days, beneath the trees, like there was a field of impossible beauty all around her. And she was right, there was. There still is.

Freeman’s

Animals

Six Shorts

ABOUT THE DOGS

Some years ago, when I walked through a stretch of unkempt parkland that connected one down-at-heel part of Delhi to another, I would often encounter a woman feeding a pack of dogs. As soon as she appeared, these residents of the park would race in from nowhere and prance around her, a blur of wagging tails and pink tongues, before settling in an orderly circle, patiently awaiting their turn. The food she brought for them was all that this ragged crew survived on, apart from garbage scraps. We chatted often because, apart from the dogs, the hills united us. She was a native of the town where I had moved to and she asked for things from there that nobody else would bring her: local sweets, seasonal fruit. The woman lived in a two-room tenement nearby, and she confessed her family thought her certifiable for sharing what little they had with strays in a park. And yet she never missed a day.

During the two long covid lockdowns across India, parks were shut. The dogs waited but nobody came, and not merely to the parks. No humans were to be seen anywhere, and this meant no kitchen scraps, no fallen food. Within days it became clear that starving strays were one of the least anticipated crises of the lockdown.

I live in a forested hamlet in the Indian Himalaya called Ranikhet. Here, as elsewhere, the market emptied out, street-food shacks closed, and people imprisoned themselves en masse. Around the shuttered tea shops the benign old mastiff everyone called Tommy, the two black pups, both called Kali, and the mangy lame fellow with no name, all began to starve. Those who normally fed them pleaded for curfew passes and funds even as unfed dogs wandered haplessly through the urban desolation vacuuming the roads for anything with a promising smell. It took days for authoritarian bureaucrats preoccupied with the finer points of lockdown discipline to register anything as inconsequential as starving dogs.

As the streets emptied, forested towns like mine began to go through a slow process of wilding. Jackals and leopards began roaming roads, verges, parking lots. They had sensed the retreat of the humans. In the way hill roads disintegrate into earth and weeds after monsoon torrents, our town reverted to forest once people left the streets and locked themselves indoors. It was like the slow blooming of a long-awaited transformation, a thing we didn’t quite understand, not as yet, because it was so new for humans to feel helpless before nature, to which it now appeared we no longer belonged. During the bird flus and the swine flus we had slaughtered millions of birds and pigs to keep ourselves safe. But this new superbug was killing only humans. Thus far, animals and plants seemed immune to it, and they were reclaiming the world.

Lonely afternoon walks began to spring scary surprises: villagers out foraging for wood in the forest came back shaken; cows grazing far from home did not return; pet dogs disappeared. The proximity of our cottage to the forest means we have always had to be careful. More so now because leopards, usually nocturnal patrollers within dog-sniffing distance from our home, were being sighted in the day. We have four dogs. They often raced off deep into ravines and valleys after deer and pheasants. It meant nothing. We were vicariously happy watching their wild abandon, their domesticity so suddenly shaken off and thrown to the winds, because they had always come back. But now, in these strange times, if they did not come back within minutes, a blazing afternoon grew as menacing as night. An innocuous straw-colored stand of grass could be camouflage for a waiting leopard, a wild creature who, like us, had lost his sense of day and night and time and place.

We had never planned to be the keepers of four dogs. They found us. Our town has one main street, and the few stray British who once passed through named it Mall Road. It has five shops, a low parapet for tea drinkers to perch on, and eight or ten resident dogs. The number of dogs is forever indeterminate because, even as puppies are born, death and disease take away the adults.

Some years ago one such dog, maybe two years old, appeared on our doorstep and sat there with an air of finality. His legs said he had come home, his eyes asked if he had. By dusk his legs had won the day. We sheltered him indoors to keep him from becoming leopard-food. That was nine years ago and he now owns the house. He has allowed in three other strays, who have joined him in allowing us a small corner of their home. For our rural, working-class neighbors, our dogs are often the topic for rueful reflections on destiny.

In a country of overwhelming inequality, human-animal conflict brings out almost as much animus as race and religion elsewhere. Hostility to dogs can run deep. The boundaries of compassion are seen as transgressions when they seem to encompass creatures who ought really to find their own sustenance in the wilderness. Sparing morsels for dogs can be seen as the profligacy of the affluent. Through the months of lockdown, and its deep, disastrous consequences for the poor, what used to be a stray accusation, often unspoken, was articulated loud and clear: people have nothing to eat and they’re feeding dogs.

Culling strays, as in the West, is illegal in India. There is, instead, a well-meaning government policy to sterilize them. Like virtually everything done by the state here, this has become one more route to corruption. Bills are fudged, accounts cooked up, and the numbers of dogs sterilized vastly inflated because they are impossible to track. On the ground, the effort to contain dog populations is largely left to charities or individuals—who are demoralized and exhausted by the Sisyphean futility of it. As a result the stray population keeps rising, as do cases of rabies. Every incident of a stray attacking a human becomes reason for another uproar against what is seen as lordly affectation, a species betrayal. People who feed strays, sterilize them, and treat their wounds have been physically attacked. Feeding cows and feral bulls, on the other hand, is celebrated, since they are thought sacred. If animals were slotted into castes, as humans are in India, dogs would be the untouchables, the outcaste, the forever suffering.

Yet stray dogs, as much as wandering cows and fakirs, have long been an archetype of Indian street life. In the nineteenth century, Shirdi Sai Baba, an Indian holy man revered equally by Hindus, Muslims, and Zoroastrians, was said to appear to his followers as a dog. His teachings included exhortations—perhaps apocryphal—to feed strays because you might be feeding god himself. Iconography shows him hand-feeding dogs or surrounded by animals. The dogs with him are never purebreds. They are “Road-Asians,” as lovable and lovely to look at as the dogs by Gauguin, roaming their localities and befriending the odd human who appears a soft touch. They move effortlessly between classes, know nothing of religion or its close companion, human warfare. The dogs with the saint of Shirdi are the humble Indian strays of indeterminate parentage, curly tails, and lopsided ears without whom our streets would be empty and unrecognizable.

Last year cities were filled with the dead and dying, all over India, rivers were choked with corpses. Every single one of us lost friends and relatives. In Delhi, cremation grounds ran out of space. What happened to the woman in the park? Her phone number doesn’t connect anymore. What happened to the dogs?

I like to think of them resurrected, bounding out again from nowhere to her, and sitting in a ring around her as she feeds them. In my head Iwill her on. I will her on eternally, because one corner of this park, to which I haven’t been able to return for two years, always has the same woman in it, with the same dogs, and I blind myself to what I have seen and read and been through by saying she will go on forever, talking to her strays in the same affectionately admonishing way as she feeds them one by one.

—Anuradha Roy

BLUE DOT

And then there was the March day I pulled into our driveway to find our remaining trees, many of them, painted with a single blue dot. Like the blue dots marked on Douglas fir, cedar, hemlock, maple, alder, up and down the McKenzie River. Meaning these trees had been given a death sentence.

I got out of the car to walk the edge of our fire-scarred woods, making my way through the cluster of blue-dotted trees to our gray house on a hill. If I was in a charitable frame of mind that morning, I might have remembered how my husband and I often spotted the curved backs of Roosevelt elk through misty rain in this same spot, their white breath steaming in the winter air; or I might have recalled the many bears Barry had chased from the recycling bin over five decades of living on this land. I could have worried about the young fox that had lately, before the outbreak of fire, sauntered to the house on given mornings, weaving through our cars and pooping on the stone path while pretending he didn’t see us watching from a window. But I crunched over the fire’s detritus consumed only by my own loss, rage already balled up in me over this new layer of damage upon damage.

Who had painted on the dots? Oregon’s department of transportation, or the subcontractor hired by the department of transportation, or the subcontractor hired by the subcontractor: I’d soon be on a convoluted path seeking someone with enough authority to explain what was happening here. I’d also soon start counting the logging trucks leaving the McKenzie River Valley with full loads, one every forty-five seconds, every thirty seconds, some trucks packed with a single tree sawed into multiple pieces, a two- or three-hundred-year-old fir, unburned, not a lick of flame on it, cut from the forest for reasons I couldn’t decipher. Now I’ve been counting trucks for fourteen months, which means I alone have witnessed tens of thousands of trees heading out of our valley to local sawmills. What do I know about forest management? Not much, but I can say with some certainty that the trees would have preferred to stay home.

The dots painted on the trees on our property were sky blue, dainty blue, a mark the size of a dessert plate, the shade of a first blanket they might wrap your infant in at the hospital. It was Temple Grandin, wasn’t it, who wrote about the necessity of calm around a cow before the whack, and maybe this is what the state arborists had in mind, too—cradling the trees into a fugue of distraction before the saw bit the bark. Almost a cheery decoration until you noticed the bar code stapled into the bottom of each trunk like a death tag tied on a toe.

Between the day of the September fire that consumed a twenty-mile stretch of our Oregon temperate rainforest valley—173,000 acres burned and about 700 structures destroyed—and his death a few swift months later, my husband arranged for a logger to take the dead and dying trees from our property. Danger trees that might hit the house (one of the few houses saved by firefighters); trees that had been burned through the bark and into the cambium layer, beyond rescue; and others whose crowns had been engulfed, halting photosynthesis. Trees left in place were preserved for a reason—the longtime logger and my husband both were certain they’d live on. Some of the oldest, strongest firs and cedars would survive. They would support the trees we’d plant over the next few years, as well as seedlings that would root in this soil on their own until, after a few human lifetimes, the forest might flourish again.

Barry was the one who’d always tended to the timber around our house, and though he’d report in about this plan and that, I didn’t involve myself more than standing on the porch to watch a tree come down, waiting for the whoosh through brush and the thud as it landed and bounced once off the ground. The boom vibrated the bottoms of my feet and up my neck into my tingling hair. I wish I’d asked more questions. I wish I’d learned the language of tree care, the tools and the logic of the forest, whatever my husband might have imparted to me before he was gone. I let myself believe he’d always be there to take care of it. During our twenty-plus years together, he cut only the standing dead trees, ones that posed a threat, and then he split the wood into logs for our fires or left rounds on the forest floor to degrade into soft duff that became the ideal bed for Doug fir and cedar seedlings. Before we built our guest cottage a few hundred feet from the house, Barry commissioned a map of every tree on the site, snugging the small building in so that only two trees had to be felled. He asked us all, me, our friends, our four daughters and their spouses and children, to stay away from the steep and shaded forest patches. For the half century he lived on this property, he made sure this land was set aside for animals to remain undisturbed by humans.

The logger brought in his skidder and his backhoe and took out eight truckloads, hundreds of trees that assured Barry and me that we had done what was right for the forest, for ourselves, for our neighbors, though my husband drooped each time a tree was loaded on the truck. Goodbye, old friend. He and I talked often about how we’d care for the rest. We would turn down offers to salvage log our land in return for obscene amounts of money. We would reason with neighbors who might accuse us of promoting tree-munching beetles and deadly fungus. How could we live with ourselves if we allowed the trees to go?

After phone calls, emails, texts about the blue-dotted trees, I was granted a meeting with a logging supervisor. He didn’t wear a mask when he emerged from his truck. He touched my shoulder and said he was sorry my husband had died, even while pronouncing me one of the nuisance homeowners. One of those pains-in-the-ass, ha ha, he’d have to soothe through what he called the process. We walked through our small forest so he could explain eminent domain, how matters of public safety allowed him to cut any conifer or deciduous tree his company’s arborist deemed dangerous, as in any tree, burned or not, that might fall and tumble to the highway and possibly, at some point, cause harm to a human being. That was the one and only criteria for painting the blue dot on a tree: a person might, in some future moment, suffer. The arborist was sanctioned to mark trees as far as two hundred feet from the road, up the hillside of our property where the largest and tallest trees lived, and there was nothing I could do about it. Or so I told myself. Maybe I simply had no more strength or will to fight the inevitable. In the weeks to come I’d stand alone to watch cranes move into the swale in front of our home so men could climb and limb branches, their saws roaring while the whomp of ancient trees resounded in my bones. One after another the trees were felled, until swaths of our land were laid bare.

*

A few weeks after the fire, when we were allowed in only if accompanied by a pilot car, Barry and I drove to the house from the apartment we’d rented in Eugene. Our second trip up since the night we were evacuated, and this time we were by ourselves. We stomped through the ash and the crumpled brush. In later weeks, we’d rake through burned debris from the lumber shed, the tool shed, paying careful attention to any remnants of the archive building where Barry had meticulously stored materials from his writing life. But now, too soon after, we could do little more than stand and stare. We poked at his burned-to-cinders truck. We sat on our charred deck, seeking a patch of shade in the 90-degree heat, and ate tomato sandwiches while we watched the goopy brown river through a scrim of ash, the river vacant of waterfowl, vacant of osprey, absent of eagle. After a few hours, we realized we had nothing to do here. No power, no water, a refrigerator and freezer full of stinking, rotten food, and gritty air almost impossible to breathe. I asked my husband if we could drive a couple miles upriver to see if spring chinook salmon had made it back to a spawning channel we often went to, though this late-September day was a beat past prime spawning time. The visit to the creek would either add to our despair or lighten it. I was willing to take the risk. When we arrived, we were both wordlessly joyous to find it was the latter. Shiny chinook as long as my thigh, torn and bruised from the long return from the ocean, dozens of them, had somehow barreled through smoldering trees in the river and swum far enough into the shallows to sweep out their redds. They’d returned despite the now-burned cottonwoods that had forever kept this cool water in shade, despite the fried grass and blackberry bushes turned brown and crisp, their berries cast on the meadow like beads from a broken necklace. Barry and I sat on our haunches to watch the splashing in the creek, reaching out to touch each other, to lay a palm on each other’s taut thighs, a quick rub of the back or shoulder. We held each other’s hands on our way back to the car.

Within minutes, an overly officious sheriff’s deputy stopped us and refused to allow us to pass without a pilot car in the lead. We couldn’t convince him to let us return to our own house a mile downriver. It was nearly two p.m., and the next pilot car was scheduled for five. The deputy insisted we must wait at the side of the road behind a line of idling refrigerated trucks for our eventual release.

Oh that long afternoon. The broiling, sticky, smoke-choked afternoon. A hideous stench in the air. The miserable hours that ticked by like a slow metronome, the sweat pouring off our faces and down our armpits, the swarms of flies that crawled across our eyes and noses. I would give about anything to return to it. Barry and I were fresh from the swelling hope of the salmon—there’s no way to be in the presence of those last-gasp fish without a renewed sense of possibility. I remember how those salmon lifted us from our gloom. On that day, we believed our community would forge on (and they have). We still believed public officials would stand with us to restore the corridor, to plant new trees and to allow the forest to recover as it knows best. The trees that could live on would be allowed to live on. We’d care for the survivors on our property. Barry had hatched a plan with his friend Dave, a California nurseryman, to replant burned parts of our woods with incense cedar and fir. We’d already seen shoots popping from scorched sword fern stumps—surely other ground cover would eke its way back, too, after a few weeks of rain.

This was the shape of our hope.

Inside our car that grueling afternoon, it was sweltering and, good god, those flies. I swatted one off Barry’s sweaty forehead and he grumbled at me for waking him—sleep was his respite. We didn’t dare roll down our windows. Outside was worse than in. The fry-an-egg heat of the road. The denuded hillside with its last scarred trees. The thick air that nearly crunched with particulates and banked like sand in our lungs. Mostly we avoided the wafting odor of seared flesh spoiling in the sun, the smell of dead bear and mountain lion, fox and vole and bushy-tailed woodrat and river otter. Deer and elk and short-tailed weasel, dog and domestic cat. The animals that died when a wild wind toppled a tree that hit a transformer that in turn sparked one of the worst wildfires in Oregon’s history. The two of us stayed put in the car, parceling our water, avoiding talk and seeking sleep. There was nothing to do but wait for our pilot, the one who would lead us out. The one, I could pretend then, who’d take us to safety, to a place of grace and healing, where we could breathe the fresh, clean air of our home and the sparkling river with its scent of trout and sun-baked boulder. Where my husband and I could sit under our towering trees and learn to begin again, holding tight to each other.

—Debra Gwartney