11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

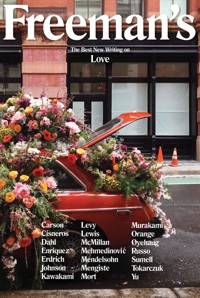

We live today in constant motion, travelling distances rapidly, small ones daily, arriving in new states. In this inaugural edition of Freeman's, a new biannual of unpublished writing, former Granta editor and NBCC president John Freeman brings together the best new fiction, nonfiction, and poetry about that electrifying moment when we arrive. Strange encounters abound. David Mitchell meets a ghost in Hiroshima Prefecture; Lydia Davis recounts her travels in the exotic territory of the Norwegian language; and in a Dave Eggers story, an elderly gentleman cannot remember why he brought a fork to a wedding. End points often turn out to be new beginnings. Louise Erdrich visits a Native American cemetery that celebrates the next journey, and in a Haruki Murakami story, an ageing actor arrives back in his true self after performing a role, discovering he has changed, becoming a new person. Featuring startling new fiction by Laura van den Berg, Helen Simpson, and Tahmima Anam, as well as stirring essays by Aleksandar Hemon, Barry Lopez, and Garnette Cadogan, Freeman's announces the arrival of an essential map to the best new writing in the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Freeman’s

Arrival

Freeman’s

Arrival

Est. 2015

Edited by

John Freeman

Grove Press UK

First published in the United States of America in 2015 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright © John Freeman, 2015

“Arizona” © Helen Simpson, 2015. “Arizona” is taken from Helen Simpson’s forthcoming collection, Cockfosters, which will be published by Jonathan Cape in the United Kingdom in November 2015.

The moral right of the authors contained herein to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

ISBN 978 1 61185 541 8

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 962 1

Printed in Great Britain

Published in collaboration with the MFA in Creative Writing at The New School

Cover and interior design by Michael Salu

Contents

Introduction

John Freeman

Six Shorts

Louise Erdrich

Kamila Shamsie

Sjón

Colum McCann

David Mitchell

Daniel Galera

Drive My Car

Haruki Murakami

In Search of Space Lost

Aleksandar Hemon

When This Happens

Ghassan Zaqtan

Mellow

Etgar Keret

SAPPHO DRIVES UPSTATE (FR. 2)

Anne Carson

Garments

Tahmima Anam

Arizona

Helen Simpson

Windfall

Ishion Hutchinson

Black and Blue

Garnette Cadogan

The Dog

Laura van den Berg

The Last Road North

Barry Lopez & Ben Huff

On a Morning

Fatin Abbas

The Nod

Michael Salu

The Mogul Gardens Near Mah, 1962

Honor Moore

The Fork

Dave Eggers

On Learning Norwegian

Lydia Davis

Contributor Notes

Introduction

John Freeman

Twenty-five years ago, I took a flight from Philadelphia to Syracuse with my mother on a regional airline that has since gone out of business. Not long into our journey, we encountered a thunderstorm. The plane was a tiny turboprop number, where you stoop to enter, luggage compartments no bigger than a bread box. Before the weather hit, it had felt cozy, like flying in a child’s toy. Then the aircraft began to dip and dive, at first gently, then, as the storm worsened, abruptly, even violently. I was a teenager, mortality but a rumor, so while my mother laughed nervously and gripped the armrest, I did what I would never do today: I leaned across her seat and looked out the window with excitement.

The sky was a deep, midnight blue, so vast it felt like the plane, our lives, were simply ideas inside the head of a much larger being. Veins of lightning lit up the night every few seconds, forking and connecting. I had seen pictures of brain scans, and I was struck by the visual similarity between an August lightning storm and how the mind works through series of electrical pulses: messages bouncing from one cell to the next, carrying dreams and shadows, bits of information to be reassembled into something that can be called thought.Oh, John, my mother said,I really don’t like this.

Eventually, my mother’s fear took over and I became very afraid. We held hands for the rest of the trip, which must have been short, but now feels endless. We had dressed for the flight, as you did then, and I sweated through my seersucker suit. It suddenly felt ominous, vain and foolish to have dandied up for something so obviously full of risk. I even pictured scraps of our clothes scattered over a mountainside in the Adirondacks.

Eventually, thankfully, we left the storm, our hands glued to one another, and landed in a light drizzle in Syracuse. I will never forget how exhilarating it was to be welcomed back into gravity’s gentler embrace. Standing on the slick corrugated metal gangway. The air creamy and ionized. The familiar mulchy scents of upstate New York. A huge smile of relief on my mother’s face when her feet touched the tarmac. I had never seen her frightened.

Every time I read, I look to re-create the feeling of arriving that day. Very little in the world that is interesting happens without risk, movement, and wonder. Yet to live constantly in this state—or even for the duration of a flight—is untenable. We need habits for comfort, and safety for sanity. For the lucky among us, though, who can make this choice rather than have it made for us, a departing flight to the edges perpetually sits on the tarmac, propellers turning, luggage loaded. It lives in the pages of books. The Greek word for porter, John Berger reminds, is “metaphor.” Stories and essays, even the right kind of poem, will take us somewhere else, put us down somewhere new.

The journal you hold in your hands is an experimentin re-creating the elemental feel of that journey. It would be traditional at this point for me to explain whyFreeman’sneeds to exist: to gripe or complain, to slight fellow travelers, to declare an aesthetic manifesto, or to apologize for bringing more. I won’t do that. Any true reader always wants more—more life, more experiences, more risk than one’s own life can contain. The hard thing, perhaps, is where to find it in one place. My hope is that, two times a year,Freeman’scan bring that to you in this form: a collection of writing grouped loosely around a theme. A collection of writing that will carry you.

Several writers in this first issue are visitors, rather than travelers, in far-flung places, and discover the difference in this distinction. David Mitchell feels what he perceives to be a ghost, lingering over his bed in a small house in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. Colum McCann describes returning home to an Ireland where the streets are rearranged, his normal orienting points scrambled. Kamila Shamsie takes friends to an inn in rural Pakistan and runs into a reminder that even though she is a citizen, her passage is granted and adjudicated by others. This feeling finds echoes in Honor Moore’s poem about arriving in Pakistan fifty years ago, in a different time.

Arriving involves coping strategies, negotiating postures, and several pieces here conjure what that feels like. Born in Jamaica, Garnette Cadogan began life walking one way; upon moving to New Orleans, and then to New York City, he has to relearn that simple act, because his skin color means something else in America. In “The Nod,” Michael Salu gives this signifying dance a science-fictional twist. Meanwhile, in his essay “In Search of Lost Space,” Aleksandar Hemon chronicles the ways his parents, Bosnian emigrants to Canada, made their new country and the plot of land they occupy their own.

Comedy lurks in all arrivals; coping crutches can backfire, often hilariously. In her story, “Arizona,” Helen Simpson conjures two women discussing the reliefs and indignities of menopause during an acupuncture sessions. An aging man in Dave Eggers’ story “The Fork” brings a utensil to his daughter’s wedding and then forgets why. Etgar Keret partakes of a nervous driver’s marijuana and gives his first major public reading so deeply under the influence he’s not sure what he says. In a version of Sappho’s Fragment 2, Anne Carson imagines what the poet would have made of a trip to upstate New York. And in her essay “On Learning Norwegian,” Lydia Davis wants to read an untranslated new novel by the Norwegian writer Dag Solstad, so she ventures off on her own into the text, using nothing but her wits and scraps of childhood German to guide her up its foreign terrain.

There are many landscapes described here, stretching from Bangladesh to Japan, but several pieces return to the familiar territory of love and marriage. The factory worker heroine of Tahmima Anam’s story “Garments” seeks refuge in a husband, and then discovers the many perils that dependency entails. In “Drive My Car,” Haruki Murakami writes of a grieving actor and his newly hired driver, a woman with whom he takes an illuminating ride into his past. Finally, in Laura van den Berg’s “Dog,” a woman waiting for her husband to sail his midlife crisis boat around the world decides he will never arrive at a shore where their marriage is safe.

The endlessly postponed arrival creates a special mixture of dread and longing. In her first published piece of fiction, Fatin Abbas paints a thrilling portrait of a village pitched between north and south in a Sudan forever tilting toward war, then toward peace. Traveling to Paris by train, Daniel Galera describes an incident that shakes him to the very core and that makes all movement seem a precursor to something darker. And in a long poem, the Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan describes the improbability of returning to a homeland that, with time, comes to seem destined (and designed) not to exist.

In an older world, boundaries would have been less important. We could, as Ishion Hutchinson does in a poem about a Utah landscape, simply appreciate the mixture of what is before us. Perhaps, too, in some cases we see boundaries where there are none. In his introduction to Ben Huff’s stunning photographs of a road in Alaska that goes nowhere, Barry Lopez ruminates on how we create a concept of nature so that we can separate ourselves from what is out there. In a humorous piece about growing up in Iceland, the novelist Sjón describes his flirtation with a reincarnation set in 1970s Reyjavik.

Perhaps the world is more benign than we give it credit for being. In a memoir of returning home to Turtle Island, Louise Erdrich visits a cemetery lit up festively for the dead’s departure and simultaneous arrival. “There are photographs attached to the stones in waterproof cases or even expensively carved by waterjet into polished granite,” she writes. “Those faces are always smiling, unaware of what is coming.” But we are; it is our burden and our gift, for it points us into the present and forward to the future, looking, as all these stories do, for that moment of contact.

Freeman’s

Arrival

Six Shorts

When I reached the Turtle Mountains and descended the long curve of hill into the center of town, I decided to continue a mile or so past an all-night gas station that functions as a desperation pharmacy for drug users and a meeting place for many of the reservation insomniacs. I went on because the August dark had fallen at last on the plains, filling the air with a dry softness. There was no cloud in the sky, the moon hadn’t risen yet, and just about now the glowing lanterns in the cemetery would be visible. These lights dot the graves old and recent, casting a wobbling greenish radiance. People of the reservation community place the lights, which are solar garden ornaments purchased in the yard sections of large discount stores, there in the ground just over their loved ones. I do not know when this started, but the impulse to light the way for our relatives and keep vigil for them on their journey goes back as far as anyone can remember. The numbers of lights grow every year as the dead increase. They seem to move or sway as modest spirits might, though that is probably an illusion cast by the shadows of the unmown grass. This late in summer, there are a few fireflies as well, stationed in the moist bushes, but they blink on and off and move erratically, and are more reminiscent perhaps of the spirits of unborn children, commemorated by the antiabortion Virgin at the front of the church—that is, the fireflies are very different from the spirits who’d had lives and bills to pay or school at least and are anchored in the dirt by solar lanterns.

The other spirits have the freedom to flit where they might, and, not having been socialized into human life, do not care anything for us. On the other hand, the dead of this graveyard and the others—the old Catholic one at the top of the hill that contains the first priests and most of my ancestors, and the traditional graveyard nobody will point out the way to—those dead are thought to look after the people of the town and bush and to exert a powerful influence.

I turned a corner and made a complete loop down onto the road that leads past several constructions by Patrick Bouvray and up toward the old Queen of Peace convent, where I like to stay.

As I passed the small wooden replicas of a church and a turtle, I remembered visiting Patrick in hope that I might persuade him to play the fiddle on my wedding day. Patrick, an old man with a long judicious face, wore the same sort of green Sears work shirts my grandfather wore, and had been sitting it seemed for many years among bicycle tires under the concrete awning in the courtyard of the retirement home. There were small cans of paint tucked against the cinder-block wall, rags, brushes, tools, pieces of an old refrigerator, and scrap wood of various shapes and thickness. Someone else had called on Patrick’s fiddle that night, but all the same I stayed on talking because I became very interested in his latest pieces, which were parked in a proud little row. Out of the reservation detritus, Patrick had made a series of wooden automobiles. They were painted in the leftover colors people gave him—an odd coral, a vibrant lavender blue, deep green. The delightful small-scale ambulance he’d made was painted an appropriate white. These conveyances were about the size for preschool children to drive, though I could more easily picture dogs behind the wheels. Patrick opened the back doors of the ambulance, doors scavenged from an old kitchen cupboard. Inside was a miniature blanketed and sheeted gurney with a convincing IV drip set up next to it. The dog would be a rez-dog beagle-Lab-shih tzu-Doberman-coyote with its limp paw bandaged. There would have to be a hole cut in the gurney for its sweeping tail. Dogs do not commit suicide, exactly, though they are known to starve themselves out of longing. This dog would have become too weak to function, I thought, and needed treatment for dehydration. I had closed the doors and thanked Patrick, who ignored me.

Now, pulling up before the convent, I parked and turned my car off. The mosquitoes would just have risen out of the tall wet reeds behind the building. Not wanting yet to brave them, I continued to sit in the car. After the strain of constant motion, I allowed my eyes to adjust to the still scene before me. Much as a person reeling from loss after loss stares at one solid thing that will not move, I watched the convent, a plainly built brick box. One of Patrick’s wooden cars, the green one, had featured a tiny grille which probably once belonged in a compact refrigerator. The grille was screwed to the front end of the car and a tiny souvenir license plate labeled “Patrick” was wired onto it. My grandfather’s first name was Patrick also. He is buried in the graveyard containing the solar lights, and he had once owned a real Model T of the type Patrick Bouvray had made. My grandfather had in fact owned a series of automobiles and was proud of each of them. His cars were often the centerpiece or focal points of family photographs and so they had been documented one after the next. He had, in addition, written about these cars to my mother and father. His letters were elaborate, exquisitely polite, and full of news of the family and of course the cars, but he never mentioned sightings of the Virgin Mary, perhaps because although he practiced Catholicism he had also been brought into the religion of our ancestors, the Midewiwin. So I would not find any hint about her there. I would have to see what I could find all on my own while referring to the newspaper clippings I had collected.

Although I have returned time and again for all of my life to my home reservation to visit relatives or teach at the community college, I have only recently begun to catalog my papers regarding this place. I’ve kept far too much paper in my life; however, I began to realize, as I made piles to burn, keep, shred, recycle, or read, that in the last pile a pattern emerged, a design which resulted in an inappropriate number of relatives flickering away on that grassy hill. As I sat before the evenly spaced bricks in the wall of the Queen of Peace I had the absurd thought that mathematics could be part of this. Events thought random have been recently theorized to be part of some infinite or infinitesimal design. I know that my dormouse storage of old paper was a nervous habit and nowhere near grand on any scale. Yet each of us may contribute an inkling of knowledge to a vastness of understanding which when we stretch our minds to consider it sickens or engulfs us. I have trouble with long division, so the idea that I might apply a mathematical construction to the sightings and the tragedies was on the face of it foolish. I knew of someone, however, who had never thought me foolish and who did math to occupy himself—a surprising hobby not just because he happens to live on a reservation. He spends his evenings drinking Blatz beer and making notations. Once he solves a problem on the walls of his little house he usually paints carefully over his neatly penciled calculations and when he is finished gives the leftover paint to Patrick. My mathematical friend’s name, too, is Patrick, but he shortens it to Pat. He is married to my aunt, LaRose. Their walls have gone from yellow to green to lavender in the past six months, and now are white. Between the colors, of course, there is the math. I visited last spring and as I sat looking at those walls, only beginning to be decorated with purposeful marks, I asked Pat what problem he’d solved between each application of the paint. He looked meaningfully at LaRose and told me that within one layer he had calculated the odds against me sitting in that very place and at that very time—they were so improbably vast when considering the age of the universe and that of all life on earth including our own descent from apes and our outward migrations or even our sudden appearance (traditionally speaking) untold millennia ago on this continent that it could be said my sitting there across from him drinking a weak cup of coffee from his plastic coffeemaker was impossible. We were not there. It was not happening. The slightly burnt taste of coffee, LaRose’s filtered cigarette, the ovenbird we both could hear in the thick patch of chokecherry, oak scrub, wild sage, and alfalfa, the sound of his reedy voice, my daughter coloring at the next table, none of this was taking place. The peace I felt at that moment surprised me. A satisfaction at not having existed in the first place. Simultaneously, I was overcome with horror at the implications for my daughter, and I rapped superstitiously on the wooden table.

Still, the memory of that sudden glimpse into fathomless nonexistence could not fail to raise the question now of whether I was truly once again sitting before the Queen of Peace convent on a dark August evening waiting for the mosquitoes to feel the chill creep into the air and kill their lust. I cracked the window. Heard the horde’s thin whine. I closed the window quickly, and waited. Behind me, my young daughter sleepily stirred in her car seat, and then fell silent. At last I left the car, looping several canvas bags over my shoulders. My daughter had awakened. I put my hand out and she caught my fingers. Her tender hand is still slightly indented at the knuckles instead of knobbed like a grown-up person’s. We walked through the utilitarian doors, past the television perpetually and soundlessly tuned to a religious station, and checked ourselves in. We were given the room at the end of the hallway where we could sleep, undisturbed, long into the morning.

Dozing off with my daughter’s small hand in mine was so relaxing in every way that I felt, myself, like a true queen of peace. Behind my eyelids pictures moved and I saw us walking down the hill, toward the graveyard lighted softly by solar lanterns. By day, our reservation graveyard is a gaudy place with lots of toys left for the deceased, plates of food, cigarettes placed on top of gravestones or sticking in the ground. Cigarettes because it takes a lot of tobacco to walk your road to the other side, where no lung disease is ever going to bother you again. There are photographs attached to the stones in waterproof cases or even expensively carved by waterjet into polished granite. Those faces are always smiling, unaware of what is coming. What they got. Yet the effect of it all is to make the dead seem happy and contented, while the living are left to deal with the hard sorrows. So I like the night graveyard better, the one we visit now in our margin of consciousness before we travel the dim tangle of neural pathways by which we will arrive at morning, where there will be pallid eggs and raisin toast to eat downstairs in the friendly kitchen, and the Sisters to talk to about all that has happened since we visited last.

—Louise Erdrich

The inn could have been the set of an L.A. noir film which dealt in broken dreams, and violence. A two-storied quadrangular building of red brick with regularly spaced off-white balconies and off-white air conditioners looked onto a generously sized garden. In the center of the garden, a large empty swimming pool with an interior of fading blue paint and cracked cement. Rusted stepladders at either end extended halfway down into the pool. A magnificent peacock roamed the gardens, like a movie star who finds herself dropped into obscurity but is determined to maintain standards. A peahen, guinea fowls, and a black and white cat made up its entourage.

Eleven of us had stopped for the night at the inn in Larkana, a band of travelers from Karachi who had come to visit the nearby ancient site of Mohenjodaro. At sunset, the inn manager laid out a long table in the garden, so we could eat beside the swimming pool and listen to each other’s ghost stories. Eventually, in varying states of terror from the stories, nine of our party wandered back to their rooms until it was just my old friend Zain and me in a darkness broken only by the low-wattage bulbs of the inn. That’s when something more unwanted than ghosts appeared: two men whose questions about the foreigners traveling with us identified them as being from Military Intelligence (the other mark of who they were was their lack of need to explain who they were before they launched into questions).

By now the second adult male in our group—Bilal—had walked out into the garden as well, and stood nearby listening as one of the men, with a neat mustache and a red polo shirt, pulled out a pad of legal paper and started to question me (he had started with Zain, because of the gender pecking order, but Zain had only just met the foreigners for the first time that morning and couldn’t be of much help). The British citizen with Pakistani antecedents didn’t interest the man from MI particularly. But then he turned his attention to The Blonde (every L.A. noir movie needs one).

What is her husband’s name? he said. She has no husband, I answered. And her source of income? She’s a writer. So her father supports her, he asserted. Is he a businessman? No, I said, she supports herself. The man looked pained by my evasions. No one earns a living from being a writer, he said. What is her real source of income?

Somehow we got through the income question, but landed straight into the peculiarity of a single woman who doesn’t live with her parents. How is this possible? said the man from MI, at which point Zain launched into a long speech about the lack of family values in the West. This was, as he intended, convincing enough to move the conversation along. To which countries had my friend traveled? Did she have siblings and what did they do for a living? Had she been to Pakistan before, and why? Had she been to India? What were her books about? On our way to Larkana our van had stopped at the mausoleum of the Bhutto family—what had she said about it? She said it made her feel sad, I replied, though in fact we hadn’t talked about it at all. This could be interpreted in many ways, said the man. What kind of sad? I decide to look appalled. There were many bodies buried there, I said. The second man, who had been silent until now, turned to his partner. It’s a graveyard! he said. Exactly, I said. A graveyard! Where is the individual of any humanity who wouldn’t feel sad in a graveyard? (Urdu allows for an extravagance of expression that came in handy at this point.)

What does she think about the Bhutto family? the man persisted. On some instinct I said, Why don’t I call her out so you can ask her yourself? For the first time, the balance of power between us shifted. No, no, he said. She’s a guest here; I can’t disturb her.

I pressed home my advantage. I have answered your questions with an open heart, I said, and now it’s getting late and I have an early flight. How long do you intend to keep me here? The man looked distressed. I have also spoken to you with an open heart, he said. At this point the inn manager, who had been smoking a few feet away, tapped the man on the shoulder and said, Let her go now. Very soon after, he did.

They kept Zain a few minutes longer, but he too took the route of outrage rather than compliance and the interrogation concluded. Once we were all back indoors Bilal, who had been listening to the whole exchange, said, What they wanted from you was money.

Zain and I replayed every detail of the encounter to each other. The truth of what Bilal said became evident. The inn manager and these two men—who were not from Military Intelligence at all—were in on the scam together.

Just wait, Bilal said. Tomorrow morning the inn manager will give us an inflated bill that will include the sum of money he’d hoped to extract from us. And so it proved. Zain demanded a breakdown of costs, and the bill reduced by half. By the time we were on the flight to Karachi I had tamed the encounter into a story of much hilarity. (The Blonde—a biographer of Eleanor Marx who cut her teeth on antiapartheid activism—particularly enjoyed my description of her as someone who studied literature, goes to see ancient ruins, and writes biographies of people who died more than a hundred years ago, and therefore can’t possibly be expected to have any political opinions about the present.)

But beneath all the hilarity, there existed this truth: The inn manager and his accomplices could run such a scam because in all of us who have grown up in Pakistan there exists a terror of the men who proffer no ID, never explicitly state whom they work for, but maintain the right to ask any questions and carry out any actions in the name of security.

The plane dipped its wings; I looked down on Larkana, home of the Bhutto family, who dominate the imagination of Pakistan as no other family does. It wasn’t just the inn, but the city—no, the nation itself—which was the set of broken dreams and violence.

—Kamila Shamsie

Hey, are any of you guys easy sleepers?”

It was a bright July night in 1978. The question was asked by one of the hippy types whom Social Services had given the task of looking after the welfare of the teenage horde that descended on the center of Reykjavík every weekend from late May to early September from the early ’50s to the end of the ’80s. I was doing the rounds with some school buddies, circling the block that took us from the parliament square, past Hótel Borg and the three discotheques we would start trying to get into as soon as we could pass for childish-looking twenty-years-olds, past the old pharmacy and the co-op shop, to the parking lot by the city’s main taxi station.

We were the third generation of kids practicing this circular wandering that was so much a thing in itself that when Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir visited Iceland in 1951 and Sartre was asked what had made the biggest impression on him during his stay, he answered that after the poem “Sonatorrek” by the Viking poet Egill Skallagrímsson—in it the poet revenges his son by writing against the ocean that took him—what most fascinated him was the sight from his hotel room of the town’s teenagers practicing pure existence by putting action before thought in the streets below.

On this sunny summer night in 1978 there was no world-famous philosopher watching us from above, but my positive answer to the question if some of us guys were easy sleepers was the first step I ever took into the mysteries of the man who in those days was considered the author of Iceland’s only original donation to the art of philosophy, Dr. Helgi Pjetursson.

In his early days Dr. Pjetursson was a world-known natural scientist specializing in geology, and many of his discoveries are still recognized as groundbreaking contributions to, amongst other things, the history of the Ice Age. But by his own account his geological studies paled in comparison with his most important work, namely, his research into the nature of sleep and dreams, formulated in series of books calledNýall, orAnnals of the New. In the epilogue of the first volume Dr. Pjetursson writes:

“Nýallis above all a scientific work. It is based upon all that has been best achieved in science and philosophy in the past, and it amends it and adds to it, in such a way that it heralds the dawn of an age of science here on earth.”

On a somewhat humbler note he explained his endeavor as “some Icelandic attempts at cosmology and biology” and “some Icelandic attempts to understand life in the universe.”

And what was it Dr. Pjetursson’s Icelandic attempts had revealed to him?

In short, that in our dreams we are connected with people on other planets. That we see with their eyes, feel what they feel, do whatever they are doing, but because their experience is processed in our brains we do not realize that it is not our own. That these beings, scattered all over the universe, are people or creatures who have died and whose astral bodies, or Kirilian aura, have been transported from their birth planet—we are only once begotten and born of a mother organism—by means of a beam called The Beam of Life and used as blueprints to reassemble them in corporeal form on their new home planets. That a force called the “Law Of Coordination” decides if our next planet will be friendly or hostile. And finally, that through mediums we can have conversations with our “dream-givers.” It is a communication that happens without any delay in the transmission because thought travels faster than light.

Welcome toCosmobiology!

The hippy who asked the question turned out to be a student of psychology at the University of Iceland and a follower of Dr. Helgi Pjetursson’s theories. As a part of his final thesis he needed guinea pigs for his dream trials. I raised my hand:

“I am an easy sleeper!”

The tests were conducted in a research laboratory normally reserved for the students of the biology department, a rudimentary setup on the top floor of a warehouse with a garage on the street level and the offices of some questionable importers on the two floors between. I guess psychology students with unorthodox ideas about the nature of dreams have to make do with whatever comes their way, but the place looked impressive enough to a fifteen-year-old kid from the suburbs who until then had seen only laboratories from sci-fi films on television.

Next to the hospital trolley that would be my bed that night there were long and wide plastic tubes hooked up to an impressive stack of machinery. Dark shadows floated back and forth under their translucent shell. They belonged to my fellow test creatures, three brown trout from Lake Thingvallavatn who were having their sense of smell measured.

I put on my pajamas, brushed my teeth, and lay down on the trolley. The hippy-turned-psychology student connected a great number of wires to my scalp. He plugged the bundle into the impressive machinery. I pulled up the blanket and fell asleep.

Each time the brain scan showed that my REM sleep was on the wane I was woken up to recount what I had just dreamt.

As science has it, I was not informed about the nature of the test beforehand, but as I was about to leave the laboratory on the morning it was finished, the psychology student told me that he was looking for evidence of two consciousnesses being at play in our minds when we dream. Unfortunately, I had failed in dreaming a dream that supported his thesis. Still, as a thank-you for my participation in the tests, he wanted to give me some books.

He handed me a plastic bag with the six volumes ofNýallby Dr. Helgi Pjetursson, nicely bound and printed in blue on the orders of the scientist, who believed that a blue text makes for deeper understanding between author and reader.

The following winter I dove into the blue sentences of Dr. Pjetursson.

Through a bus driver I discovered that a splinter group from theNýall Societymet every Thursday night in the old town of Reykjavík. With the help of Gudrún the Medium, a middle-aged woman who worked in a fish factory during the day but served as a gateway between worlds in her spare time, theNýallistspracticed their science by talking to people who by dying had gained direct experience of the cosmobiological universe and could bear witness to the fact that all of Dr. Pjetursson’s ideas were right. During coffee breaks members of the group shared their ideas about various subjects that occupied them. One was trying to prove that the Keops pyramid was built as a monument to the greatness of the Icelandic language; another had found evidence in the Bible that on the day of the crucifixion Jesus Christ had been four years old; a third was occupied with questions about what the static noise of radios really was.

My teenage mind swimming in Dr. Pjetursson’s theories on death and dreams, at these meetings all my cravings for the weird were catered to—until the summer of 1979, when I found my next source of inspiration, Surrealism. There I was provided with a key element in the life of any young man, and one that was wholly missing from the Nýall: The Erotic.

I will always be thankful for my year with theNýallists. And till the end of my days I will cherish my copy of the superbly namedÍslendingar áöðrum hnöttum(Icelanders on Other Planets). A booklet written under the influence of Cosmobiology, it is an attempt by an Icelandic farmer to connect with his dead wife through automatic writing which results in a literary genre that can only be called “Peasant Science Fiction.” If Dr. Helgi Pjetursson was as right about this subject as he was about the Ice Age, it is the best handbook for the afterlife I’ve ever read.

So, I am prepared.

The day I suddenly wake up in the glowing moss of a yellow mountainside, naked but warm from the reddish light of two suns, where five-legged birds flit through the air meowing like cats, and I see a small group of people walking toward me dressed as Icelandic peasants at the turn of the twentieth century, I will know I have died.

I will remember that at the moment of death I was beamed across the depths of space, to a distant galaxy, a foreign solar system, to a new planet where my body was reassembled according to my aural blueprint.

It will be the first day of the second stage of my everlasting life.

“Oh, there he is!”

One of the men from my welcoming group will raise me to my feet—he looks like my father in his confirmation photograph, and I will soon discover that he actually is my deceased father—and two women (the younger one has pale blue skin and furry hands, as she has come here from a different world from ours) will wrap me in a blanket woven from the three-layered, green wool of the bus-sized sheep grazing in the valley below.

I have arrived. Now it is my turn to provide strange dream experiences to the easy sleepers back home on Earth.

—Sjón

For a short while after the death of Seamus Heaney in 2013, the rumor floated around Dublin that the airport might be named after him. With flights from JFK. Or Reagan International. Or Charles de Gaulle. Or Benazir Bhutto. Maybe a fatal touchdown from George Bush International. Or even some flights that might have connected originally in Jorge Chávez or Il Carravagio or Frederico García Lorca International.

When it comes to departures and arrivals, the dead, and even the living, meet in many forms.

At Dublin Airport I can never remember whether the Departures gates are upstairs or downstairs. Somehow it matters very much. I get confused at times, especially in the brand-new Terminal Two. I stray to the Arrivals area when really I want to leave. Or upon arriving, I’ll wander past the Departures gates and ponder if I made a mistake in touching down in the first place. There goes that old dead self leaving twenty-nine years ago, wearing skinny jeans, dragging a torn backpack. The new self walks the other direction, wider, slower, formal, with a new rhythm to his accent. All those ideas that once made him soar along a foot from the ground are somehow forgotten. At the rankdownstairs he can’t remember if it’s a “taxi”or a “cab” that he should hail. No matter. The low-tide smell of the city returns.

A few years ago I used to make a habit, upon arriving in Dublin, of going to see my favorite Irish writer, Ben Kiely. I’d go by bus, or foot, or bicycle, or taxi, to his house on the Morehampton Road. He and his partner Frances would open the door and take me in, even unannounced. Ben had been important to me since at a young age I first read his short stories, which I still believe are amongst the finest of the twentieth century.

This time around, though, I was working far too hard at being busy. I had only about an hour and a half before I went to the airport again. Small matter. I drove my rental car into Donnybrook and pulled up outside 119 Morehampton Road and looked for a parking space, but there was none. A Garda car came up behind me. Its lights flashed. I gave them a wave and moved on.

I did an illegal turn down near the shops in Donnybrook. A woman in a brand-new Merc gave me the middle finger. I blew her a kiss. She didn’t laugh. I reversed again and corrected, slowly crawled up the street.

Still no parking. A bus behind me blared. I was in, it seems, the wrong lane. I would have blared my horn if I was behind me too—in life we seem to want to split our feathers and leave both halves in flight. To hell with it, I pulled the car up onto the pavement and hit the hazard lights. If nothing else, I’d just drop the book through the letter box. But again the cops pulled up behind me. This time a Ban Garda got out and told me with a distinct lack of ceremony that I’d better move or else I’d be fined. That meant I would miss my departure, which meant, in essence, that I would miss my arrival home. But wasn’t I home anyway?

I began to feel what I can only call an emigrant’s panic. To be a man of two countries, his hands in the dark pockets of each. These were streets I used to know. Nothing was the same. I grew more and more desperate, charging down streets, looking for a parking space, looking for the correct turn back to Kiely’s house. The miles clicked up on the car until eventually I was up beyond Milltown and caught in a traffic jam for the M50 motorway.

My confession: I sat in the traffic jam and had a fair idea that Ben would die sometime soon. He had survived a long time and he had given his readers and friends an inordinate amount of pleasure, but here I was, stuck in a Dublin traffic jam, and only this story to tell, a book of mine in the front seat, a novel, signed to him, ungiven. Someone behind me beeped again. I was home and I didn’t recognize where I sat. I saw the sign for the airport. I took it. Ben died a few months later.

Cooking our lives down under boiling heat, the one thing we can’t evaporate away is our original country. It would do no moral good to depart from Heaney International. It’s a brain-peeling process to walk through an airport with the knowledge that you might not be coming back for a long time. Sure, there is an arrival on the far side. But all arrivals are departures too. Like two mirrors put face-to-face, the leaving and the coming swallow each other at a thousand points, lost eventually in the black border of each other.

It’s just as well that the supporters of Heaney decided to not to go ahead with the plan. All ports—but especially Irish ports—reek of sadness, even in the Arrivals area where the cheap balloons temporarily bob.

What is the scene of arrival and where is the point of departure? Good question for a poet. Heaney knew the answers.

A few years ago the busiest place in Dublin Airport was the short-term parking lot. There were several reasons for this. Ireland was diseased with money. The economy was on fire. Porsches pulled in. Range Rovers. Lamborghinis. The drivers parked their cars as close as possible to the terminal. Often their machines were too wide for one spot and they purposefully straddled two. They ran inside. A weekend trip in Lanzaroti. A Spurs game in London. A horse race in Paris. They didn’t care how much the parking would eventually cost.

But every now and then an older, dented car stayed beyond a weekend. Then a few more days. The Dublin Airport employees glanced inside. Nothing too unusual. Some papers on the front seat. A set of keys in the well of the dashboard. Maybe a child’s stuffed animal in the backseat, forgotten. A few more days passed until eventually the airport employees began to recognize these cars as part of a pattern. The papers in the front seat were mortgage demands. The keys in the dashboard were the keys of a house abandoned. The stuffed animal in the backseat was part of a life that a child would never know. These young Irish families were going away forever. There could be no return. Short-term parking. Long-term loss. Sydney, Chicago, Buenos Aires, Paris would be their next arrival.

To abandon everything is a familiar story, perhaps especially to a poet. What we look for, then, is some internal rhyme, most likely just out of reach.

—Colum McCann

In 1996, I was living alone on the ground floor of a musty old house at the edge of a Japanese town called Kabe in Hiroshima Prefecture. Kabe is built where theŌtagawa River emerges from the mountains and enters the delta plain over which Hiroshima and its suburbs nowadays sprawl. In 1945 an American Boeing B-29 dropped an atomic bomb (famously named “Little Boy”) onto the city. Uncounted hundreds or thousands of people not incinerated in the blast made their way north along theŌtagawa in the vain hope of finding help. Many died of their burns before they reached Kabe, and many died of radiation poisoning in the days and weeks that followed. The precise number of total casualties as a result of the bomb is impossible to reckon, but estimates range from 90,000 to 166,000, with about half the deaths—45,000 to 83,000—occurring on the first day. By any measure, this is a hellish quantity of sudden death. In the Japanese context, this also means a vast number of restless ghosts denied the Buddhist funerary rites required for a smooth passage to the next world.