13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

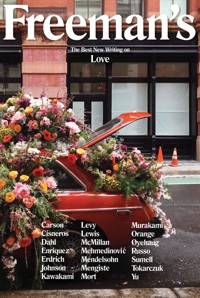

Day by day, tweet by tweet, it often feels like our world is run on hate. Invective. Cruelty and sadism. But is it possible the greatest and most powerful force is love? In the newest issue of this acclaimed series, Freeman'sLove asks this question, bringing together literary heavyweights like Richard Russo, Anne Carson, Sandra Cisneros, Louise Erdrich, Haruki Murakami, Tommy Orange and Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk alongside emerging writers such as Andres Felipe Solano and Semezdin Mehmedinovic. Together, the pieces comprise a stunning exploration of the complexities of love, tracing it from its earliest stirrings, to the forbidden places where it emerges against reason, to loss so deep it changes the color of perception. In a time of contentiousness and flagrant abuse, this issue promises what only love can bring: a balm of complexity and warmth.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Previous Issues

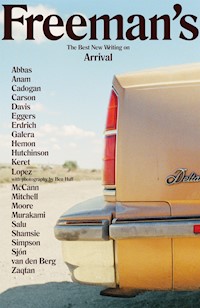

Freeman’s: Arrival

Freeman’s: Family

Freeman’s: Home

Freeman’s: The Future of New Writing

Freeman’s: Power

Freeman’s: California

First published in the United States of America in 2020 by Grove Atlantic

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © 2020 by John Freeman

Managing Editor: Julia Berner-Tobin

Copy Editor: Kirsten Giebutowski

All pieces not included in the list below are copyright © 2020 by the author of the piece. Permission to use any individual piece must be obtained from its author.

The moral right of the authors contained herein to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 452 7

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 891 4

Printed in Great Britain

Contents

Introduction

John Freeman

Seven Shorts

Maaza Mengiste

Daniel Mendelsohn

Anne Carson

Mariana Enriquez

An Yu

Tommy Orange

Matt Sumell

“Heaven with a Capital H”

Mieko Kawakami

Postcard from New Mexico

Deborah Levy

Snowflake

Semezdin Mehmedinović

Stone Love

Louise Erdrich

The Snowman

Daisy Johnson

Poet’s Biography

Valzhyna Mort

Apples

Gunnhild Øyehaug

Exploding Cigar of Love

Sandra Cisneros

On a Stone Pillow

Haruki Murakami

How to Manage

Niels Fredrik Dahl

Good People

Richard Russo

High Fidelity

Robin Coste Lewis

Seams

Olga Tokarczuk

swan

Andrew McMillan

Contributor Notes

About the Editor

Introduction

JOHN FREEMAN

The first time I sent a love letter, I misspelled “love.”

Or nearly did.

This would have been around 1979. I was lacing up my shoes to sprint over to my classmate Betsy’s house when my mother found me. Where are you going? I hadn’t yet learned to feel ashamed of myself, so I told her.

I’m going to put a love letter in her mailbox.

Can I see?

My mother spoke that way. Not, let me see; or hand it here. But, can I see? I showed her the love letter.

Oh honey, you might want to change this. You spell “love” like this.

She wrote the word down carefully in her perfect looping penmanship. Seeing the way she put down words, like each one was loved, would make me cry years later, after she’d died, at the sight of things she’d written.

I looked at the word. It didn’t look more like love now that she’d written it. Rather, it was like she had told me a leaf was bark, and bark a leaf. Did it matter? Who made such arbitrary decisions? Sometimes you just loev someone.

I corrected the word, laced my shoes, and ran off—a reverse bank robbery. Leaving something behind, not taking it.

I never heard back—or at least not directly. Perhaps this is why so many five-year-olds’ love letters are structured like multiple-choice questions. Maybe I hadn’t yet learned that love was something you waited for to return. Like a boomerang. After all, I lived then in love’s constant, endless return. I loved my father and sometimes he would walk by and pat my head, like I was a dog. I liked that. My older brother often crawled into my bed at night when he was scared and the warmth of my body made it easier for him to sleep. I liked that too.

As a child I recall feeling so full of love it was natural to constantly give it away. To old people. Strangers. The marching band. They walked right by my house, throwing batons and people in the air. We got pets to have something around us to love, even if they ran away, like all our gerbils. We developed crushes the way rivers grow tributaries. Everywhere I went, love was operating in some constant, unquestionable fashion—like gravity.

Childhood, when it’s safe, teaches us to love. I was lucky, so lucky, to have had the kind of childhood I was given. It would be years before I learned that love might endanger me; that love could break me; that I could love someone and they wouldn’t love me back. Or maybe they’d use that love against me. When I was lacing up my shoes, I was sending out love into a world that had always, only, returned my love in some fashion or other—an attitude I see in children now and hold my breath.

One fundamental difference between us and children is how we wear these lessons, which accumulate with age. Whether it makes us wary, or skeptical, or hopeful, or estranged, or physically tense. How we move our bodies is shaped by how love has entered our lives. Where the stress fell, where its tenderness turned a receipt of love into a habit of being. Where its departure left scars. Our body becomes the way we hold these contradictions: love’s pleasures and its pain.

Still, no matter how small the weight, or how odd the contradiction, love is too much for any one body to hold, and so we tell stories about love, write poems to it, tell memoirs of its survival. Love is the biggest and most complex emotion, the most powerful, it cannot be held in the palm of our hand—even when it’s a child’s hand resting there. So we put it into the only container made stronger by such contradictions—a story.

This collection celebrates writing on love, and it also makes a case for the love story to be about more than romantic love. What if love could be felt in more directions than between one human (or two) and another? Louise Erdrich writes a poem from the perspective of a stone to the earth. What knows more about longevity than a stone?

Time alters so much here in its wind tunnel. In Semezdin Mehmedinović’s profoundly moving essay, he describes how, caring for his wife in the wake of a stroke, he has to repair time for both of them. Soldering here (Washington, D.C.) with there (Sarajevo); her body (now broken) with her bodies (all the selves he knew through the years), he sings a psalm to the power of love to hold so much together. He plays games to trick her memory back to life, and thus restores to them their great treasure—how love held them, these two people, together, for so many years.

Of course time presents challenges to lovers united in relative health, too. How to love someone when they cannot go where you go, each night, away from the land of Nod? This is Daniel Mendelsohn’s great dilemma, as an insomniac. How do you make a spouse know what you feel, Niels Fredrik Dahl’s poem wonders, when your words, repeated over the years, have worn a path to the ear? How do you wear someone else’s past, if their troubles—Maaza Mengiste thinks, entering a world with her elder’s name—are not your own? How do you show it love? What do you owe it? In her brief piece, An Yu recalls encountering an old woman who made shoes one night in Shanghai—with her flat hard accent so reminiscent of Yu’s own family, she draws love forth from Yu, unthinkingly, in the night.

Familiarity cuts so many ways in love. It can give you the safety to play a game, as Robin Coste Lewis describes her parents playing, in the sexy poem, “High Fidelity.” Or that familiarity can lead to a wizened, shared sense of entanglement. In her hilarious poem, Sandra Cisneros reminds of how love can feel like a dance we know the steps to, and cannot resist—even when we know someone might end up on the floor. In Richard Russo’s short story, a couple conducting an illicit affair confronts the end of their time together—something which they knew loomed on the horizon from the very beginning.

How to tell a story when you know the end? How to reengineer that story so it reflects the ways a tale sometimes unfolds with one party more entrapped than entangled? Gunnhild Øyehaug’s story performs this feat by slipping her yarn—of an older man and a younger woman—through several trapdoors until it’s back in the hands of the woman who lived the tale, not the man who prompted it. Valzhyna Mort’s poem elegantly skewers the question of whose biography matters, the speaker’s, which is lived, or the poet’s, whose work he was desperate to hand her. Anne Carson, who has spent a lifetime in academia, describes the kinds of interactions that often undergird the power dynamics therein, driven not only by age and intellect, but also by an accompanying male entitlement.

* * *

It’s a hard time to believe in love. So many spectacles of its opposite are on display. It is tempting to abandon real love and simply believe in its fantasy, or only in love for the absolutely pure and cute. Dogs, cats, pets of the earth. Matt Sumell has arrived at a version of this, all while holding his integrity in hand like an odd hat. In his heartbreaking piece he describes how he has made a moral choice to love what no one wants to love: the dogs people throw away.

To write love today demands we engage such depths, where anger and shame meet longing and comfort, lest we make a fantasy of love. Hindsight helps, too. In her wondrously honest piece about an ill-advised affair she had in her youth in Paris, Mariana Enriquez marvels at the risks her younger self took for the dream of a French romance. Maybe it’s not just in youth that we do this; perhaps we’re all just making it up as we go along, pulling from a set of impulses that we discover, as Tommy Orange does, writing about learning to love his family, are so full of danger that to contemplate them for too long could mean giving up on love entirely.

What a joy it is, then, when one finds a love about which one can say—this I know. It’s as magical as, say, swimming in the snow, as Deborah Levy puts it; or as strange as a one-night stand, as Haruki Murakami’s characters experience it. Luminescent, strange, almost holy, but also: how to decide if it is enough? How much light do we need an encounter to contain to be called love? Can a night ventured be called love? Is there a duration required? Must it last a day, a week, a year?

How desperately we need each other, to ask these questions. As siblings, fellow travelers, friends. In an excerpt of Mieko Kawakami’s novel in progress, “Heaven with a Capital H,” two pals go to a museum, and love becomes the way they reinforce each other’s moods as they try to define what it is that brings them joy. Love is how they allow the other to even ask for it. Similarly, more darkly, in Daisy Johnson’s story one sister—who is well—makes a creature of mud and stone for the other, who is dying. The narrator realizes the competition for attention with her sister is running out, that for the rest of time she will be left with a lack. That it is time for her to simply provide the unasked for gift of happiness.

Stories, poems, literature allow us to see love’s evolution. Even if we are born to vast, encompassing love, we can learn to appreciate it by seeing how it changes. Whether our parents exist for us or not; whether they stay together or not; whether our own lovers return our care, or not. Whether they survive an illness —or, in the case of Olga Tokarczuk’s devastating story—not. These questions almost always are beyond our control. What a vast network of exposure this reveals; we are all, constantly, facing the ravishment love entails. In his series of poems, “swan,” Andrew McMillan shows how one way to live in a world of such precariousness is to take over one’s own evolution. To say here, take me like this; or this; or this. Tell me how to be. Watch me evolve for you.

And anyone who has ever waited for the answer to a message sent across town will hold their breath.

Seven Shorts

A FUTURE HOPE

When I was born, the story goes, my young and inexperienced mother was frightened of the sudden and new responsibilities I represented. It was my grandmother who nurtured me and raised us both until we were able to move into our own as mother and daughter. I was named after my grandmother, a fact of my life that filled me with a strange and glorious feeling. Sharing her name brought me close to something transcendent. It made me feel both young and old: a girl living next to a future version of herself, evident in my grandmother’s aged, loving figure. I remember moments of pure delight when a neighbor or a relative would call out my name, and she would answer. That response felt like an answer from my future self to the one in the present. I had no words to articulate this back then, of course. I thought of it as a game, a joyful one.

My grandmother and I were especially close. The first real devastation of my young life was leaving her and my grandfather when my parents, my little brother, and I left Ethiopia for good. She was my first definition of love and compassion, so when she gave me a bracelet when I was twelve years old during one of my visits back, I knew she was giving me tangible, solid proof of our bond. She asked me to wear it all the time to remember her while I was in America.

The bracelet, a thin and delicate band of gold, had faint scratches that spoke of its age. It pressed gently against my palm as I held it, both fragile and durable at the same time. As I balanced it in my hand, I was so moved that I could not speak except to say, “I’ll never take it off, I promise.”

My mother was sitting with us. “Let me have it first,” she said. “I’ll give you the bracelet that your grandmother gave me when I was your age. I’ll melt them together and you’ll have one piece that’s joined and from both of us.”

When the work was done a few days later, my mother slipped the bracelet on my wrist and adjusted it. I stared at it, moving my arm up and down, growing accustomed to the new weight. The bracelet was still delicate, but it was fashioned in a braided design as if two ropes were woven together, then melded into one piece. My mother reminded me of my promise, and I vowed to her and to my grandmother both that I would never take it off. It would be a small reminder of the two of them, of Ethiopia and family and the distance that had forced itself between me and so many whom I loved. It was a path back home, becoming a part of me until, as the years progressed, I could not imagine myself without it. It would be, I once said to my husband, like cutting off my arm.

The bracelet stayed on my wrist. It accompanied me through middle school and high school and college. It graduated with me into the work world. And as the years passed and I returned to Ethiopia for visits, I noticed the way my grandmother would look down at my wrist and nod her head. When she held my hand, I often felt her tap the bracelet and smile. My promise was a silent affirmation of our bond; it was the expression of my gratitude for all she had done for me. I knew that my journey to America did not begin with me. I was well aware that those who leave can do so because of those who stay behind. Every step forward I made came at a cost that was beyond the parameters of money, and often invisible; it was visible in what my American life lacked: those dearest to me. On each trip I made to see my grandmother and grandfather, I felt my conviction strengthen: I would never take the bracelet off, no matter what.

To promise: from the Latin pro (forward) and mittere (to send). To send forward, send forth, to prepare a path before one’s arrival, to push ahead, to charge through, to enter new space, to migrate. A promise is a shift into uncharted territory that we have no way of predicting. It is a claim made on our future selves by the person we are in the present moment. A promise beckons an unshaped world and attempts to control it. It is a willful suspension of disbelief, a naïve assertion that the future will bend in our favor and that what we call our existence is intractable and immutable: predictable. It is hope. It is also foolish.

“What do you mean it doesn’t come off?” a TSA agent asked me in an airport in Italy. “Of course it comes off.” And she grabbed my arm roughly and held it tight as she tugged at the bracelet to pull it off my wrist.

I felt cold air wash across the back of my head. Every word dropped out of existence except one: “No.” I shook my head and tried to pull back my arm but she held on tightly. “No,” I said again, becoming immobile. “No.”

For years, it had been relatively easy to keep my promise. There had never been a need to take off my bracelet. It became a permanent part of me, like a birthmark. But I was in an airport and this was 2016 and the world had new fears and precautions that I could not have predicted when I had made my vow as a child. That day, in that airport in Italy, it wasn’t enough to say, “It doesn’t come off.” It wasn’t good enough to say simply, “No.”

“No? What do you mean, no?” And she called someone else to help her even though I was too stunned and shocked to struggle. Even though the bracelet was delicate and held no weight at all. Even though my wrist was caught in her grip and there was nowhere I could go.

How do you say to two agents holding your forearm and your wrist that there are oaths you will not break, even if your arm does? How do you explain that a promise made in childhood can solidify to become as sturdy as the strongest bone? That it will snap before it bends? That certain vows require more from us than others? That they form us and to undo their bind means to unravel completely?

I cannot remember why the agents stopped their attempt to take off my bracelet. Maybe it was because they recognized my deep, muted terror. Maybe they understood something about precious objects that would mean nothing to someone else. Maybe they realized that there was nothing about me to fear. Maybe they saw what they had become in my eyes. As I kept saying no, they stopped. They dropped my arm and as I held my wrist, they told me to get my luggage and go on. I turned around and looked at the first security agent. I could not speak, but I would like to think that I didn’t need to.

Since then, I have been asked to step aside for other inspections. I have volunteered to do so before I’ve been asked. I’ve said that the bracelet will not come off. I’ve said that it simply does not come off. I’ve said that I cannot take it off, and I have seen how those declarations have sometimes prompted recognition in TSA agents who then wave me on. I have tried to prepare myself, though, for the inevitable because one day it will happen.

I made a promise as a child believing that the world would bend to my oath. I did not foresee the many ways that this world would try to inflict so much damage on those words—my words. Back then, I did not know enough to accommodate for the wreckage that time can exact on everything around me. I imagined that I would stay the same as the moment in which I made that vow: I promise you, I swear to you. And yet: what “I” remains untouched by life?

Several years after my grandmother’s death, I found myself standing on my grandfather’s veranda. He was dying and had begged to see me once more. I could not travel back to Ethiopia in time to see my grandmother before she died, and he wanted to make sure this would not happen with us. When he opened the door and saw me, he began to weep and call out my name. And as he repeated it, bowed by the weight of the word, I knew that he cried for my grandmother. I knew that when he looked at me, he wept for the other Maaza who was dead. The one who was alive and standing at the doorstep was less real than the one who had left him behind. I cannot imagine what it was like for him to stand in front of me, on his way to dying, on his way to our last shattering farewell, and understand that his utterance of my name would also call forth a ghost. As I watched him struggle to regain his composure, all I could do was grip my bracelet and cry. To promise, to send forth, to migrate. To hope.

—Maaza Mengiste

SLEEPLESS LOVE

Jonas is sleeping: deeply, obliviously. Not I. With him as with all the others, I am the watcher, the wakeful one. This is our fourth date, and as I watch him sleeping, his back to me, the arc of his right shoulder with its oddly hollow, birdlike blade inches away, the deep furrow that runs down the center of his back, sloping away and disappearing behind the cotton blanket, that landscape that I love so much, I know there will not be a fifth date.

Once again, I have made the same mistake.

For with him as with the others there is not only this landscape, the salty terrain of flesh, the furrows and hills that invite exploration and discovery, there is that other landscape, the one where he cannot join me. As the hours slide through late night to early morning, I feel myself entering this private terrain. First there is the upward slog from the plush dark valley of eleven o’clock, with its dense comfortable underbrush: the magazines piled on the duvet, the whiskey glass gleaming amber on the bedside table, the detritus of the day before, among which I can happily prowl, convincing myself that I am still of the day. But as the little wooden mid-century modern electric alarm clock on the nightstand whirs and clicks and eleven spirals away into twelve I feel myself as if hiking, struggling toward the darkly silhouetted peak of midnight; then, on the other side of that crest, the cautious, icy descent down into the valley of one o’clock—still close enough to midnight to feel connected to the day before and, therefore, to some kind of safety. But as one o’clock creeps toward two and then three and finally three-thirty, it is as if I am skittering across a vast floe of ice: the continent of true insomnia, the white place where the sky is indistinguishable from the horizon and the horizon from the ground, where there are no landmarks, no railings or stanchions, no tracks, not even the scratchy tracks of birds. I know that I am completely alone in this place, and when I finally summon the courage to look down at Jonas (or Bill, or Glen, or Greg, or Jake, or Travis, or Rafaël, whoever it may have been over the decades), it is, I imagine, how someone who finds himself aboard a sinking ship might look down from the juddering deck, as the stern rises toward the moon, at some other passenger who, out of cunning or (more likely) sheer dumb luck, has found safety in a lifeboat and is already curled there at the bottom of the shallow boat in a blanket.

It is like being a ghost and looking at the living.

This is my landscape, the place where I live for seven hours every night of my life. Even when I was a child, I wasn’t able to sleep well. In the crib I would turn over constantly, anxiously; in the narrow wooden bed that my father built for me when I was old enough to have a bed of my own, I would read long after we were supposed to turn off the lights, dreading the moment when I would have to put away my book for good and face the blank night. In the college dormitory room I shared with two other students the deep rising and falling of my roommates’ breathing was like the sound of surf, but even that wouldn’t lull me to sleep; I would count their breaths into the hundreds until, around five-thirty, I would collapse into an hour’s shiftless sleep.

It was at university that I slept with (well) another man for the first time, and I realize now that what I was hoping for more than anything—more than the fulfillment of some adolescent fantasy of perfect like-mindedness, more than the sheer pleasure of sex—that what I was hoping to get more than anything from these lovers was someone to share my sleeplessness with: someone who would, at last, accompany me through the white trackless exile of my insomnia.

And yet, as if by some perfect, cruel asymmetry of the psyche, every youth, every man I was to fall in love with thereafter would be a profound sleeper. One would collapse so totally into an almost coma-like sleep after sex that, the first time we went to bed together, I was afraid he might have had some kind of cerebral embolism, might even have died; another was so hard to wake up that on our first morning together, so as not to miss an important editorial meeting, I had to leave him sleeping there, and wondered as I took the subway downtown just who he was, actually, and whether my apartment would be intact when I returned home. One would softly cry, like a toddler, when I jostled him awake from a nap, so thoroughly did he inhabit his sleep. “It’s like I’m in a beautiful garden and you’re pulling me away from it back onto asphalt,” he once said to me, unforgiving. But whatever their individual habits, they all shared the ability to fall swiftly into sleep, leaving me beside them to watch the wooden clock and begin my awful journey while they remained unconscious through the night. Which is to say, all of them managed to make me feel alone even when I was with them. Unconsciously, instinctively, like water buffalo in a drought that can smell a standing pool twenty miles away and move sluggishly toward the place where they think it is, only to find dried mud where the water was only minutes before, I have managed over the years to find these perfect sleepers, these companions who are not companions, these partners who cannot accompany me where I go each night.

The fact that I continue to make my nightly journey alone suggests to me, at least, that there are never really “lessons” in love; the place in the psyche that is the source of how we love is so deep that our attempts to reach it, to tunnel down to it and bring light and air there, must always fail. I go to a party, a meeting, a bar; I go online. I see a man whom the conscious part of me beholds and begins to desire; whom my conscious self approaches at the party or meeting or bar or the site or the app and talks to and decides is suitable because this man shares my love of swimming or Mahler or gardening; the conscious part of me will do what we all do, will type his number on my iPhone and wait sickeningly for a text or a call and then, when it comes, will grow giddy and anxious until the moment when we go for a drink or dinner and then, when the drink or the dinner leads back to my place or his place, things will unfold as they do. And it is only then, when we go to the bed and get in and he falls soundly asleep, curled in his lifeboat while I scan the familiar horizon, the shrubbery of 23:00 and the silhouetted peak of midnight, the valley of 01:00 and the dread frostbitten plains of 03:30, do I realize that the conscious mind is the fool, the rebellious and ultimately powerless servant of the unconscious mind which wants, in the end, and for whatever mysterious reasons, to be alone.

—Daniel Mendelsohn

LIVES OF THE VISITING LECTURER

Pool

The hotel has a pool. The hotel has no pool. The hotel has a pool but it is three strokes long. The hotel has no pool but there is a university pool. The university pool is closed for a swim meet. The university pool is not closed but requires a keycard. There is no university or university pool but there is an ocean, loch, lake, fjord, river, local spa. These are wildly pounding, freezing cold, rocky, muddy, reedy or crazy-expensive nonetheless all will be well, the visiting lecturer knows as she slides into the water. You too are made of stars, someone is saying later as she passes the breakfast room.

Plato’s Roaring Darkness

Noticing a poster for a talk (by last year’s visiting lecturer) about Plato, she is cast back to the winter as a graduate student she’d fancied herself a demimondaine because her mentor liked to give her suppers at posh restaurants in return for light fondling in his office. He was a large, monumentally ugly man who had written important books on Plato. She was unused to attention. He smelled like dust. She was twenty-two and thought him too old to worry about, anyway that’s how things worked in those days. Together they attended Emeritus Professor George Grube’s “On First Looking into Plato’s Republic.” She remembers now nothing of the lecture except that Professor Grube talked into the microphone and consulted his notes alternately, as he was so nearly blind he had to bring his face right down to the podium to read, thus becoming inaudible. It was later that night or the next day in his office that she and her mentor had a discussion about flesh and to his asking whether or not she “could see her way to being kind to him” she had answered no. Some years later, making notes for a memoir, she will shave the anecdote down. “After dinner I went to hear an old man, nearly blind, who spoke of the frustration and despair he found in the central books of Plato’s Republic.” And she will add, taking things in a different direction, “Men are allowed to decay in public as a woman is not.”