12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

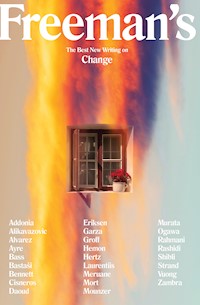

The Covid-19 pandemic forced many of us to reimagine our homes, work, relationships and adapt to a new way of life - one with far fewer possibilities for interaction. And yet, in this period of intense isolation, we've faced dilemmas which are nearly universal. How to love, to care for aging parents, to find a home, attend to a planet in flux, fight for justice. This vast range of experiences is captured by our greatest storytellers, essayists and poets in Freeman's: Change. Some pieces explore the small moments that serve as new routines in a life lived at home, as in Joshua Bennett's essay, where a Coltrane playlist sets the stage for early morning dances with his newborn son. Sometimes, it's the absence of change that drives us to the edge. In Lina Mounzer's 'The Gamble,' a father's incessant hope for a better life festers and sinks the whole family after they leave Lebanon during the Civil War. And in 'Final Days,' Sayaka Murata imagines a future without aging, where people must choose how and when they want to die, consulting guidebooks like Let's Die Naturally! Super Deaths for Adults & The Best Spots. With new writing from Julia Alvarez, Sandra Cisneros, Zahia Rahman, Yoko Ogawa, Yasmine El Rashidi, Lina Meruane and Aleksandar Hemon, and featuring work from never-before-published writers like Elizabeth Ayre, Freeman's: Change opens a window into the many-sided ways we adapt.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Previous Issues

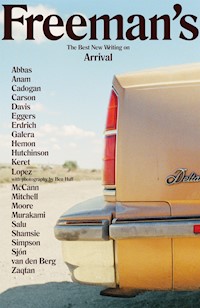

Freeman’s: Arrival

Freeman’s:Family

Freeman’s: Home

Freeman’s: The Future of New Writing

Freeman’s: Power

Freeman’s: California

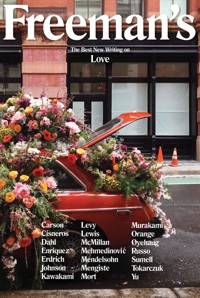

Freeman’s: Love

First published in the United States of America in 2021 by Grove Atlantic First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Grove Press UK,

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © 2021 by John Freeman

Managing Editor: Julia Berner-Tobin

Copy Editor: Kirsten Giebutowski

All pieces are copyright © 2021 by the author of the piece. Permission to use any individual piece must be obtained from its author.

“Chick Truck” by Yoko Ogawa was first published in 2006 in

Umi (Tokyo: Shinchosha, pp. 107-135).

“Up Our Sleeves” by Jakuta Alikavazovic was first published in the September 18, 2020 issue of Libération.

The moral right of the authors contained herein to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 434 3

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 879 2

Printed in Great Britain

Contents

Introduction

John Freeman

Seven Shorts

Joshua Bennett

Christy NaMee Eriksen

Lauren Groff

Sulaiman Addonia

Jakuta Alikavazovic

Kyle Dillon Hertz

Rick Bass

The Gamble

Lina Mounzer

Künstlerroman

Ocean Vuong

Final Days

Sayaka Murata

The River

Aleksandar Hemon

A Bright and Ambitious Good-Hearted Leftist

Adania Shibli

A Boy With a Machine Gun Waves to Me

Sandra Cisneros

Algeria: Held in Reserve

Zahia Rahmani

Chick Truck

Yoko Ogawa

Library or Life

Alejandro Zambra

Election Night

Elizabeth Ayre

The Night Train

Mark Strand

Becoming a White Sheet

Kamel Daoud

Where Are We Now?

Yasmine El Rashidi

Try to Summarize a Mutilated Year

Valzhyna Mort

Siarhiej Prylucki.

Dmitry Rubin

Julia Cimafiejeva

Uladzimir Liankievič

Her Skin So Lovely

Lina Meruane

Ariadne in Bloomingdale’s

Julia Alvarez

Bread

Lana Bastašić

The way the tides

Rickey Laurentiis

Dream Man

Cristina Rivera Garz

Contributor Notes

About the Editor

Introduction

JOHN FREEMAN

It’s hard to imagine, but the heavens, as we know them, are younger than Shakespeare. They’re practically newborn when compared to the practice of mastectomy, which was safely performed as far back as 3500 BC. And they’re but a novelty when compared to technology such as the hand-axe, which is half-amillion years old. As late as the early 1500s, the night sky was gazed upon like a ceiling. A gracefully illustrated, but essentially depthless decoration, tilting through our view—comets like brief scars of newness—earth at the center.

It took a mathematician from what is today Poland—Nicolaus Copernicus—a lifetime of study, and one gloriously titled posthumous book (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) to displace earth from the center of the universe. Before he died, Copernicus dedicated his essay to the pope in a move that seems part entreaty, part apology. He knew what he was proposing was nearly blasphemous. It proved to have enormous implications for faith.

It also kicked off a wave of scientific discovery, which Galileo Galilei turned into a full-fledged revolution.

Change can come this way—a door shoved open by a radical idea, truth finally let free. On the back of Copernicus’s proofs, Galileo began to replace an immutable world with one in constant flux. Among his greatest inventions were the instruments to see it change: the reflector telescope, with which he studied the moon; the scientific method, which applied to every known phenomenon; the thermometer; even a version of the compass. In thanks for his efforts, Galileo was tried in 1633 by the Church for heresy and convicted. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest, a period during which he wrote two of his greatest books.

Change is often resisted not simply for what it threatens, but for the new responsibilities it forces upon us. If the universe is a living, dying, and constantly evolving organism, as Galileo suspected, and other astronomers like William Herschel began to surmise in the late eighteenth century, what does this mean about our planet? Can we simply use it with impunity? Meanwhile, on we tilt, observers or passersby, engaged or aloof, meteors through a brief slash of time.

Centuries on from the pre-Copernican era, we can feel somehow made by that old universe; as in, we long for some degree of immutability. For a love which is forever; parents who do not age; the stability of work or occupation. The need to sustain a belief in permanence has created whole religions; art forms; enlightened or regressive political movements. Tents of comfort in the face of what the body knows: we are born into a world of constant change.

From the cells of our body, to the nations we call home, change defines the parameters of life. We are marked by it, and by how and what we resist. We are made by the ways we narrativize our reactions to rupture; how we adapt to what we must accept. Coming in the wake of the worst global pandemic since the ongoing AIDS crisis, this issue of Freeman’s aims to gather stories, poems, essays, and reports from this shifting front.

* * *

We begin with the life of Galileo—not the astronomer, but the newborn son of poet Joshua Bennett. In a brief essay Bennett describes the rituals he and his child—christened August Galileo, after the playwright and the scientist (and a speech of W.E.B. Du Bois’s titled after him) begin every morning. They sing to a songbook, they dance to a soundtrack. Why don’t we make up new habits? This tends to be the question behind every story or novel Sayaka Murata writes, including her latest story, “Final Days,” set in an imagined world of endless life, in which a craze for early death sweeps across Japan.

Sometimes change itself becomes the fantasized ritual. In her powerful memoir, Lina Mounzer recalls the forever delayed, yet constantly imagined improvements her father predicted would transform their lives after they left Lebanon during its civil war. Keeping this hope aloft against the realities of their lives in post-emigration Montreal drives him to the addictive cycles of the lottery. Sulaiman Addonia grew up in a refugee camp in East Africa and learned a similar lesson there about the world’s indifference to his attempts to wish it better.

Observing the world’s indifference can occasion a search for new metaphors. In Ocean Vuong’s exquisite short piece, a man’s life is narrated backwards, and with each step into the before time, the inexorability of what just happened lifts away, like smoke. Meantime, after her father dies of Covid, Christy NaMee Eriksen learns she has inadvertently—using the word “avalanche” for how it feels—captured how suddenness is often the accumulation of unbearable pressures.

We have names for such pressures, for stories where such force is euphemized. History is one of them. In her essay on Algeria, Zahia Rahmani reveals how the name of a nation can become a repository for the million unremarked-upon simultaneous changes—and hands—that make a place what it is. Her daring piece, which weaves personal essay, colonial historiography, and twenty-first-century travelogue, suggests one nimble way to tell that story more honestly.

So many people, through no fault of their own, are trapped in tropes they did not elect. This can be infuriating . . . and lethal. Lana Bastašić’s vivid short story shows the thin line between these poles as a teenage girl walks home across a city where men pursue her threateningly. In Yoko Ogawa’s story, a gentler interpretation of youth and age spins about a man and a child who must step briefly out of their roles to save each other from crushing lonelinesses.

Another arena in which change is formalized are elections. It’s a small word for the tumult of chaos, hope, bamboozlement, brave activism, and brutal suppression which fall upon its remit. Elizabeth Ayre’s stylish remembrance of the night of November 3rd, 2020, recalls some part of that day’s singularity, also the desultoriness which can arise out of the suspicions nothing will change.

Watching the unchangeable in its inexorable march in circles can move one to states of psychosis and rage, grief and communion. Lassitude. The narrator of Kamel Daoud’s short story visits all these way stations as his mother begins to die, and regresses to the girl she once was, editing her son from memory in favor of one who left home long ago. In Kyle Dillon Hertz’s short memoir, the author winds up in hospital, overtaken by the damage he’s done to his own heart with drugs; he finds his communion in the offering of help from a close friend.

* * *

We pass the lamp of hope to hands we trust may keep it safe. Another word for history might be: the story of what happens to that lamp. Several pieces in this issue imagine their way into such handoffs. Aleksandar Hemon’s poem about Walter Benjamin appreciates how fantastical was the philosopher’s journey in 1940 across the Pyrenees away from Nazis, what force of mind it must have taken to avoid the clutch of despair. Great change, sometimes, can only be faced in the moment. Yasmine El Rashidi’s memoir of her family’s move from their treasured home upon the Nile reveals how melancholic this passage is when it has been a long time coming.

Adaptation to great change does not always mean acceptance. It can coexist with modes of resistance, with equivocal feeling, with regret. These are all part of Adania Shibli’s luminescent tale of a man building a small business of bus lines in contemporary Palestine. The acrobatics of his adjustment to the daily disruptions of life under occupation are seen in sharp contrast to the steady grind of building a business.

Change can lag behind its necessity by decades, centuries even, out of which develop strategies of deflection. Rickey Laurentiis’s intricately beautiful poem enacts the way their gender flummoxes its so called viewers, turning the poem’s speaker into a one-person help desk of explanation. Style, in this ecstatic mode, is beyond fashion, a crucial buffer. In her bracing memoir, Lauren Groff explores how going back to her hometown is impossible, for it would render her that too exposed, too seen, too vulnerable child she once was—so each night she sacrifices this child to the lake in her mind.

Great change often makes martyrs of people who simply can deflect no longer. For the past year, poet and translator Valzhyna Mort has read the news from her home country of Belarus in search of names of the dead. Here she translates poets who have found themselves unable to turn away from their government’s tyranny any longer, on the front lines of political change. Their words are burning embers of a not-yet-made historical moment.

Some of the most imagistic writing here reveals the human figure amidst great flux. We need this in art and poetry to understand where we are and what is happening. In her poem, stark as a black-and-white photograph, Sandra Cisneros captures the face of a boy sitting in the back of a truck, a machine gun in his lap. A soldier in Mexico’s sprawling narco-violence. Julia Alvarez’s brilliant poem neatly inverts the framework of background and foreground, the poet remembering herself in the 1970s: a recent graduate living in Queens who would, along the course of a subway journey that took her into Manhattan to work at a department store, transform herself into a very different woman.

There are no do-overs, no backstops to certain types of change. We may create games, as Jakuta Alikavazovic writes in her short essay, to allow ourselves the fantasy that we can go back to the way things were before. But these games cannot be played forever. Alejandro Zambra spent years fantasizing about downsizing his library, he writes in his playful, heartfelt memoir, but when he finally does so it is because he has left the family whom he began it with—a fact which gives his new bookshelves a melancholic spareness. In a stilling posthumous poem, Mark Strand shows how the game many of us played growing up—peering out a moving car, bus, or train, listing what one sees—when played as an adult produces very different results. Among them, respect for the blur of time, an awareness of ghosts.

In ancient mythology, change often comes in the form of a monster. A daemon, a spectral presence. Before Galileo, a comet was often viewed as portending sudden catastrophe. Even though we know such things to be superstitious, we need to dream our fears to survive change. To push them outside ourselves in forms of art, narration, design. In Lina Meruane’s incredible gothic story, a woman trapped inside a house with her two sons during a pandemic faces the barbarity of the ultimate sacrifice demanded of her as a mother. Meanwhile, in Cristina Rivera Garza’s astonishing rewriting of the myth of a mermaid, we watch a man blown sideways by a woman not his wife. Only this time they’re on a mountain, and here the sea is a canopy of green.

We have other recording devices for what has happened beyond our lifetimes, for noting what we’ve survived, aside from what Galileo, Newton, and others gave us. Not to mention the narrative strategies writer like Jane Austen, Toni Morrison, and Barry Lopez among others pioneered as ways to remember history. A forest, after all, is a living record of change. In the carbon content of plant life and the patterning of tree rings lurks a nearly complete story of the past, if we can only listen. In a dispatch from the forests of Montana, where human intervention has begun to deform the landscape’s own ability to heal and recover, Rick Bass delivers a stirring call to pay attention to the reverberations which travel through wood. Some of you, perhaps, reading this right now, sit upon a piece of it. Maybe, if this is a paper copy of Freeman’s, you are reading from it. Later tonight, maybe an even smaller number of you will gaze out the window through it. Galileo’s original telescope was made of two pieces of wood, joined together, to form a tube. And so he saw the heavens from earth. What stories it tells, what dramas it contains—like the stars assembled here.

Seven Shorts

GIANT STEPS

There is a playlist on my phone that’s built entirely from the genius of John Coltrane, and I’ve been playing it for my son since the day he was born. It begins with Trane’s cover of “My Favorite Things.” In truth, I have no idea how it ends, because we never get there. By the time we arrive at “Lush Life” or “Equinox” during the azure hours of the early morning, he’s usually asleep again, or else we have decided that we’re done dancing across the kitchen and are onto another activity. We have a few hours before Mom wakes up. The options unfold like a field before us. Most days, we move right from the dances to time with poems, as that feels like the most logical sequence. Early mornings, after all, are made for music.

Some recent favorites—and you should know that my sense of the work’s reception is based on feedback in the form of ear-to-ear smiles, and yelling in the midst of one or more stanzas in direct succession—include Joy Priest’s “Little Lamp,” Al Young’s “The Mountains of California: Part I,” and “Something New Under the Sun” by Steve Scafidi. The Scafidi poem opens with the sentence It would have to shine, and every one of the days that begins this way seems to. Even deep gray weather takes on new resonance: hours to spend watching sheets of rain re-arrange the backyard, making it much too muddy for our family dog, Apollo V, to play in. He doesn’t always take this sort of shift in his routine well, Apollo, as he has recently had to adjust to having a new family member, and is still getting used to the feeling that not all of our attention is focused on him.

This conundrum is mostly my fault. And in more ways than one, perhaps, naming him as I did for a god of poetry and light, a space shuttle, the theater where my mother first saw Smokey Robinson sing, and a cinematic revision of the greatest boxer of all time, his modern legacy renewed in the body of Michael B. Jordan. I’m named after a book in the Bible and an older brother who died before I was born. My mother takes her first name from her grandmother, and her second from the tall, Puerto Rican nurse in the delivery room where my grandmother first guided her into the world.

My son, August Galileo, has a name that emerges from both African diaspora literature and a family commitment to studying the heavens. He is named for the legendary poet and playwright, August Wilson, as well as for Black August: the yearly commemorative event in which people all across the world celebrate not only the revolutionary legacy of George Jackson, who was slain on August 21, 1971, but also the practice of freedom across a much larger stretch of human history; the founding of the Underground Railroad, the Nat Turner Rebellion, and the Haitian Revolution. Galileo is meant to gesture both toward the father of modern astronomy, and the 1908 Fisk University speech delivered by W.E.B. Du Bois that bears his name: “Galileo Galilei.” It is one of the most powerful pieces of oratory I have ever encountered. In it, Du Bois writes: “And you, graduates of Fisk University, are the watchmen on the outer wall. And you, Fisk University, Intangible but real Personality, builded of Song and Sorrow, and the Spirits of Just Men made perfect, are as one standing Galileo—wise before the Vision of Death and the Bribe of the Lie.”

Names are an incantation of a certain kind. August Galileo reminds us, and will hopefully remind our son, to have courage in the face of unthinkable odds. Persistence in the midst of the seemingly impossible. An unflinching dedication to wonder, respect for the essential drama of human life, and the ceremonies that make it worthwhile.

The other big difference since August’s arrival—aside from the new routine at sunrise—is that there are toys everywhere. Many of which have names that are not to be found on the boxes we purchased them in: the Wolf Throne (his swing), the Device (a gray baby sling), and the Rattle Snail (a rattle shaped just like a snail). This ever-expanding collective of objects makes it hard to walk through the living room, but a joy to be there. Once Mom comes downstairs, it’s party time once again. We throw on a KAYTRANADA deejay set and dance until we are tired, falling to the couch in unison, where we rest for a while.

One of the great gifts of the Black expressive tradition is that it refuses the notion of human immortality—especially as it is often imagined in our secular modernity, through private property or conquest—and yet gives you moments where you feel invincible, endless. We do not live forever. But we do live on. We live for the children. We engage in protracted struggle so that they might inherit a planet worthy of their loveliness. While I once understood this largely in the abstract, this sense of things now animates my days. I can’t hear Coltrane without thinking of my boy arriving here just a few months ago on a Sunday night, hours before dawn. Two weeks ago, while looking through old records, I found a copy of Trane’s debut with Atlantic, Giant Steps. It felt like a sign. New beginnings, infinite promise. The intractable power of a single human breath, enough to shift the known world on its axis.

—Joshua Bennett

DEEP PERSISTENT SLAB

Previously I only used the word avalanche as a verb. It basically meant, “I am crying and I cannot stop.”

Still, owning a home in an avalanche zone, I have recently been compelled to try to make sense of my city’s urban avalanche advisories. They use the word avalanche in a way that means “a massive amount of snow, ice, and rocks falling down a mountainside.”

Please forgive my errors or oversimplification, but here’s my attempt at translating. It appears that it matters what kind of day a mountain is having. Depending on the weather, snow settles into different kinds of layers, and these layers stack up over time. What I understand to be our biggest current problem is what’s called a “deep persistent slab.”

A deep persistent slab is a big piece of snow with a very weak layer inside it. The weak layer is so deep you almost don’t know it’s there unless you’re looking for it. Another layer inside it might be a crust, which in a way amplifies the weak layer because you could poke the crust a long ways away and the poke would reverberate across the crust, and this is how one light touch could trigger an avalanche of giant proportions. No matter how soft or how strong the snow is, if you touch it when or where it is tender, it will drop to the depth and the width of its weakest part. And so an avalanche is not just snow, and it is not just the trigger, it is the result of holding too much when you were not properly grounded.

On the same day, one year apart, I packed a bag. That’s a lie; one year ago my friend Melissa packed my bag, because I was avalanching on the living room floor. My sister had called. My father was fighting for his life in the ICU. At that time they said they didn’t think he would make it through the night, and I could not fly out until morning.

Sometimes you don’t get a warning

I can’t separate the experience of saying goodbye to the home my dad built me from the experience of saying goodbye to my dad at this precise time last year. There are all kinds of natural disasters. They say our bodies remember grief anniversaries, which baffles me since my own grief is very bad at time management. Perhaps grief is just a weak layer and it doesn’t matter how deep it’s buried. A smell or a bird or the sunrise on a particular day can always touch it.

Grief, I mean the director of emergency management, knocked on my door Saturday morning to explain the danger of wishing for the best.

But it’s a blessing, isn’t it, to have a chance. To have a minute. To take the irreplaceable with you.

If the avalanche were to hit our homes, they predicted it could be fourteen feet deep going fifty-seven mph across a quarter mile. I really can’t see how a human house could survive that, and yet I am familiar with praying against the odds. My father survived his first night, and on the second night, he briefly woke up. It was today, one year ago: my mother’s birthday. A miracle, they said, and the nurses had chills. It filled me with catastrophic hope.

When we dug our way out, we told my dad that we loved him, and that he didn’t have to worry about us. This was the third day. We said goodbye, because we were warned; and it’s better to say goodbye and walk away than to be destroyed inside it. That was 364 days ago. Some mornings I can walk on that layer and some mornings I’m still buried under the snow.

What type of weather do we want? my friends asked, and I don’t know enough avalanche science beyond “we want spring” to answer this. In grief counseling, no weather is bad; I think the goal is that you heal your deep persistent layers so no slab could kill you. The director of emergency management lowered the danger level from “extreme” to “high,” so I know that with the right conditions even an avalanche can change. The weak layer can strengthen, the facets can face the wind. The load can lighten and aspects can melt. It can be touched without breaking.

Often it just takes time

—Christy NaMee Eriksen

LAKE

Some nights, that deep cold lake brings my child self back to me again. This is often without my consent. I want no part of the person I was then, or to be back in the town of those years that made and held me. Cooperstown, where I was born, is a speck in-the-middle-of-nowhere New York, so small it is officially a hamlet, so pretty with its flower boxes and groomed hedges and American flags that it has been transformed into an object, its citizens offering the place up every summer for the pleasure of thousands of boys and men who come for baseball and nostalgia and a glimpse of their own child-ghosts. Can a town be objectified like a woman? If she is Cooperstown, she can.

In my dreams, the lake first sets me down at the Presbyterian church atop Pioneer Street, thin, tall, ancient, a building made of whittled bones, where I was long ago given the gift of awe but also of torment, the three-hour services with an indifferently talented choir and the crotch of my itchy woolen tights slowly sliding down my thighs. Through the rest of the week, I would bear the oppressive weight of a male god who was always furious at the tiny rebellions of my mind. I was defective because I feared far more than I loved. A mouse, this child me, blonde, pale, blinking, bewildered, scared. In the dreams, even as I repudiate her, this child self goes away from the church as fast as she can, flying down the hill toward Main Street. It is empty of cars and people, the single stoplight westward along the street shining against the wet asphalt, glazing the windows of the bakery in alternate red and gold and green, the cord of the great flagpole in the center of the street where I stand chiming in the small wind. From there, the street scoops downhill to Lakefront Park, where the statue of Natty Bumppo hunts with his dog, until at last it empties out into the dark glower of the lake.

It is this strange long lake, a block away, that peered from over the lawn into the windows of my childhood bedroom. Before I rose from bed every morning I would look out to gauge the lake’s mood that day, which could change with terrifying swiftness. There would be temper tantrums when the dust-devils grabbed loose snow up from the ice and spun it to frantic dancing; placid happy days of sunlight on the warm, navy blue August water; pensive sheets of fog lifting gently off its surface in an orange autumn dawn; thunderstorms descending from Cherry Valley nine miles north in luxurious woolen sheets of gray. We had a party every Fourth of July, where from our lawn we’d watch the fireworks double themselves on the water below, the hills grabbing the thunder of the explosions and tossing it back and forth between them until a new blast came and the old thunder was lost. The lake has always been pure intensity, beauty, terror to me.

And in my dreams the child me stands hapless at the flagpole, trying to resist its pull, but inevitably the lake draws my ghost down, toward this wild and uncontrollable and inescapable depth of feeling.

This is what I dislike, the way that as a child I felt absolutely everything, and it was all unbearable. I had a good childhood, I was fed and loved, but I was born unskinned, a girl bleeding out her hot red emotion everywhere. There were days I felt I would die of the sound of the crows eating the corn in my father’s garden or the taste of the honey I stole from the back of the pantry—sugar forbidden in my house, pleasure suspect—and spread surreptitiously on the hot biscuits I baked before swim practice. The membrane between my interior self and the world was easily rent. I could contain nothing within me. I am not quite sure how I survived. And everywhere I went in town, even in places where you couldn’t see the lake, you knew it was there, gleaming; it was my overlarge mirror, unskinned like me, shining the sky back to itself, too emotional, too much, too dangerous, you could drown in it.

A dreamer at last awakens into life. The lake’s nighttime draw fades until I wake in the mornings as an adult who has grown the calluses necessary to keep herself alive. Still, even as an adult, I am reluctant to come home. It has been almost a decade since I’ve been back to Cooperstown; my parents have moved away, there is no obvious reason to return. And so I have kept the place safe, stuck in aspic, somewhere deep inside. There is a beauty in this resistance, because the layers of time and space in me can be preserved unmixed. In this way, the bend where Lake Street descends to Council Rock exists as many things all at once: the spot where one Halloween in middle school, I lay down in the dark road to scare myself and was nearly run over by some quiet car, where I stepped on a flotsam board and drove a nail through my foot, where my first friend and I crouched, seven years old, scraping wet stones on stones to paint our faces and make ourselves warriors. To see the ways the town has changed, the trees loved decades ago dead and vanished, the buildings altered, the old friends startlingly old and stout and gray, looking like their parents as they bend their heads into the wind, crossing the street, no, no thank you, I cannot, it would be too much. The fragile defenses I have constructed against the overwhelm of the world would break. Anyone could see straight into my depths. And so I sacrifice, night after night, my child self to the lake, both self and lake through dream rendered subject, not object. Perhaps a ghost is a person and a place dreaming at the same time. I let my subconscious draw this trembling, world-sick child down to Lakefront Park, which in my sleep is simultaneously draped in night and too brightly daylit, the sun blazing the water hurts my eyes. In this place I once saw a flock of mallards peck a sickly drake to death, and my golden retriever would hie herself there to lap up the grease the motel’s restaurant set outside to cool, and my lovelorn best friend and I would eat whole pints of ice cream to find a foothold for self-hatred, and I once waded in after a frisbee and sank up to my hips in duck shit and had to be pulled out with a rope. All of it, all, remains as it has ever been, living, tender, wild.

—Lauren Groff

THE POWER OF ABSENCE:CHILDHOOD BUSINESS VENTURES IN A REFUGEE CAMP

The mother of my childhood friend was a sex worker. I remember how, when I encountered them outside our school in the mornings, he’d hug her tightly as if he wanted to collect the fragments she had broken into under the weight of clients during the night, piecing her together again between his arms.

Many parents in our camp were only complete and present in the mirrors of our imaginations. My own mother was away, working in Saudi Arabia as a domestic servant for a princess, and had left me and my siblings under the care of my maternal grandmother when I was about three. But like my friend, I too embraced my mother every morning, even with the Red Sea between us. I embraced her in the old memories she left behind, and the new ones that wafted into my world from the cassette tapes she sent us from Jeddah along with the framed color photo which my grandmother had hung on the mud wall of our hut.