18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

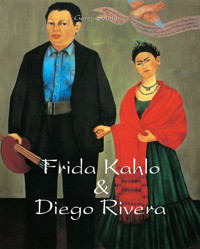

They met in 1928; Frida Kahlo was then 21 years old and Diego Rivera was twice her age. He was already an international reference, she only aspired to become one. An intense artistic creation, along with pain and suffering, was generated by this tormented union, in particular for Frida. On both continents, America and Europe, these committed artists proclaimed their freedom and left behind them the traces of their exceptional talent. In this book, Gerry Souter brings together both biographies and underlines with passion the link which existed between the two greatest Mexican artists of the 20th century.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Author: Gerry Souter

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© Victor Arnautoff

© Georges Braque, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© José Clemente Orozco, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SOMAAP, México

© Estate of Pablo Picasso/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA

© David Alfaro Siqueiros, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SOMAAP, México

© Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo n°2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Image Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-64461-777-9

Gerry Souter

Frida Kahlo

&

Contents

Frida Kahlo Beneath the Mirror

Introduction

The Wild Thing

Death of Innocence

Señora Diego Rivera

Affair of the Art

“I urgently need the dough!”

“Long live joy, life, Diego...”

Conclusion

Diego Rivera His Art and His Passions

Foreword

From Training to Mastership

His New Exile to Europe or His Artistic Quest

Between Painting and Politics

A Communist Cheered by Americans

The Last Years or the Return to the Country

List of Illustrations

Notes

Frida Kahlo Beneath the Mirror

Introduction

Her serene face encircled in a wreath of flaming hair, the broken, pinned, stitched, cleft and withered husk that once contained Frida Kahlo surrendered to the crematory’s flames. The blaze heating the iron slab that had become her final bed replaced dead flesh with the purity of powdered ash and put a period – full stop – to the Judas body that had contained her spirit. Her incandescent image in death was no less real than her portraits in life.

Frida Kahlo should have died 30 years earlier in a horrendous bus accident, but her pierced, wrecked body held together long enough to create a legend and a collection of work that resurfaced 30 years after her death. Her paintings struck sparks in a new world prepared to recognise and embrace her gifts.

Her paintings formed a visual diary, an outward manifestation of her inward dialog that was, all too often, a scream of pain. Her paintings gave shape to memories, to landscapes of the imagination, to scenes glimpsed and faces studied.

The painter and the person are one and inseparable and yet she wore many masks. With intimates, Frida dominated any room with her witty, brash commentary, her singular identification with the peasants of Mexico and yet her distance from them, her taunting of the Europeans and their posturing beneath banners: Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Expressionists, Surrealists, Social Realists, etc. in search of money and rich patrons, or a seat in the academies.

And yet, as her work matured, she desired recognition for herself and those paintings once given away as keepsakes. What had begun as a pastime quickly usurped her life.

The singular consistent joy in her life was Diego Rivera, her husband, her frog prince, a fat Communist with bulging eyes, wild hair and a reputation as a lady killer. She endured his infidelities and countered with affairs of her own on three continents consorting with both strong men and desirable women.

But in the end, Diego and Frida always came back to each other like two wounded animals, ripped apart with their art and politics and volcanic temperaments and held together with the tenuous red ribbon of their love.

Her paintings on metal, board and canvas with their flat muralist perspectives, hard edges and unrepentant sweeps of local colour reflected his influence. But where Diego painted what he saw on the surface, she eviscerated herself and became her subjects.

As Frida’s facility with the medium and mature grasp of her expression sharpened in the 1940s, that Judas body betrayed her and took away her ability to realise all the images pouring from her exhausted psyche. Soon there was nothing left but narcotics and a quart of brandy a day.

Frida Kahlo, The Dream or The Bed, 1940. Oil on canvas, 74 x 98.5 cm. Isidore Ducasse Collection, France.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait, 1930. Oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm. Private collection, Boston.

Frida Kahlo, Pancho Villa and Adelita, c. 1927. Oil on canvas, 65 x 45 cm. Gabierno del Estado de Tlaxcala, Instituto Tlaxcalteca de Cultura, Museo de Arte de Tlaxcala, Tlaxcala.

The Wild Thing

As a young girl, wherever she went she seemed to run as if there was so little time left to her and so much to be done. Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón was born on July 6, 1907 in Coyoacán, Mexico. By that time running, hiding, and learning to quickly identify which army was approaching the village were everyday survival skills for Mexican civilians. Frida eventually dropped the German spelling of her name, inherited from her father, Wilhelm (changed to Guillermo), a Hungarian raised in Nuremberg. However, she used the German “Frieda” spelling in some of her intimate letters. Her mother, the former Matilde Calderón, a devout Catholic and a mestiza of mixed Indian and European lineage, held deeply conservative and religious views of a woman’s place in the world. On the other hand, Frida’s father was an artist, a photographer of some note who pushed her to think for herself. Guillermo was surrounded by daughters in La Casa Azul (the Blue House) at the corner of Londres and Allende Streets in Coyoacán. Amidst all the traditional domesticity, he fastened onto Frida as a surrogate son who would follow his steps into the creative arts. He became her very first mentor that set her aside from traditional roles accepted by the majority of Mexican women. She became his photographic assistant and began to learn the trade, though with little enthusiasm for the photographic medium. She travelled with him to be there if he suffered one of his epileptic seizures.

Guillermo Kahlo was a proud, fastidious man of regular habits and many intellectual pursuits from the enjoyment of fine classical music – he played almost daily on a small German piano – to his own painting and appreciation of art. His work in oil and watercolour was undistinguished, but it fascinated Frida to watch him use the small brush strokes of a photo retoucher to create scenes on a bare canvas instead of just removing double chins from vain portrait customers.

He rigidly maintained his own duality: outwardly active, but trapped with his epilepsy as he regained consciousness lying in the street, felled by a grand mal seizure with Frida kneeling at his side holding the ether bottle near his nose, making sure his camera was not stolen. He played his music and read from his large library, but inside was constantly in turmoil about money to support his family. He wore what Frida described as a “tranquil” mask. She adopted that self-control, or at least the appearance of it, in the darkest moments of her life, never willing to display any public face that revealed what lay behind the stoic image.

Frida Kahlo was spoiled, indulged and impressionable. Her father’s success landed him a job with the government of Porfirio Díaz, photographing Mexican architecture as a sort of advertisement to lure foreign investment. Since 1876 Díaz had enjoyed some 30 years as president of Mexico and adopted a Darwinian philosophy toward governing the Mexican people. This “survival of the fittest” concept meant virtually all government money and programs went to building up the rich and successful while ignoring less productive peasants. Mexico became the economic darling of international trade as countries took advantage of its mineral wealth and cheap labour. European customs and culture ruled while native Mexican and Indian traditions languished. Díaz personally selected Guillermo Kahlo to show the best side of Mexico to foreign investors, vaulting the photographer from an itinerant portraitist into the coveted middle class.

Diego Rivera, Nude of Frida Kahlo, 1930. Lithography, 44 x 30 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

Diego Rivera, Nude of Frida Kahlo, 1930. Lithography, 44 x 30 cm. Signed and dated on bottom, right hand corner: D.R. 30. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

Poem published byEl Universal Ilustrado

November 30, 1922

MEMORY

I had smiled. Nothing else. But suddenly I knew

In the depth of my silence

He was following me. Like my shadow, blameless and light.

In the night, a song sobbed...

The Indians lengthened, winding, through the alleys of the town.

A harp and a jarana were the music, and the smiling dark skinned girls were the happiness

In the background, behind the “Zócalo”, the river shined and darkened, like the moments of my life.

He followed me.

I ended up crying, isolated in the porch of the parish church, protected by my bolita shawl, drenched with my tears.

Letter to Alejandro Gómez Arias

April 25, 1927

Yesterday I was very sick and very sad; you can’t imagine the level of desperation one can reach being this sick. I feel a dreadful discomfort that I can’t describe and sometimes I have a pain that nothing can take away. They were going to put the plaster cast on me today, but it’ll probably be Tuesday or Wednesday because my dad hasn’t had the money – and it costs sixty pesos. And it’s not the money so much, because they could easily get it. [The problem is that] nobody at home believes that I’m really sick, because I can’t even say it, since my mother, who is the only one who worries a little bit [about me], is ill. And they say it’s my fault, that I’m very imprudent. So nobody suffers, despairs, and all that, but me. I can’t write much because I can barely bend down; I can’t walk because my leg hurts terribly. I’m already tired of reading – I don’t have anything nice to read – I can’t do anything but cry, and sometimes I can’t even do that. Nothing amuses me; I don’t have a single distraction – only sorrows – and all the people that pay me a visit annoy me very much. [...] You can’t imagine how these four walls exasperate me. Everything! There’s no way I can describe to you my desperation.

Frida Kahlo, Accident, 1926. Pencil on paper, 20 x 27 cm. Coronel Collection, Cuernavaca.

Kahlo wasted no time in buying a lot in the nearby suburb of Coyoacán on the outskirts of Mexico City and building La Casa Azul, a traditional Mexican wrap-around home – painted a deep blue with red trim – with its rooms opening onto a central courtyard. In 1922, to assure her a better than average education, he also entered Frida into the free National Preparatory School in San Ildefonso. She became one of 35 girls admitted to the school’s enrollment of 2,000 students and rose to become a class character alongside other male pupils who became some of Mexico’s leading intellectuals and government leaders. She devoured her new freedom from mind-numbing domestic chores and hung out with a number of cliques within the school’s social structure. She found a real sense of belonging with the Cachuchas gang of intellectual bohemians – named after the type of hat they wore. Leading this motley elitist mob was Alejandro Gómez Arias, who reiterated in countless speeches that a new enlightenment for Mexico required “optimism, sacrifice, love, joy” and bold leadership. His good looks, confident manner and impressive intellect drew Frida to him.

All her life, Frida attracted men of this stripe and, once conquered, each became enmeshed in her passionate, possessive web. But each conquest also puzzled the country girl as she pondered what these strong decisive men saw in her.

She was short, dark, slender and a cripple. At age 13, Frida had been felled by a bout of polio that withered her right leg leaving it shorter than her left. Neighbourhood children taunted her with shouts of, “pata de palo” or “peg leg”. To conceal her affliction, she wore layers of stockings on her thin leg and had a half-inch added to the heel of her shoe. Considering the state of medicine in Mexico of the 1920s – hot walnut oil baths and calcium doses – she was lucky to be alive. To further compensate for her limp, she plunged into sports: running, boxing, swimming and wrestling, every strenuous activity available to girls. But her greatest sport was intellectual debate, and with Arias she found a true soul-mate.

By 1923 they were lovers and sharing hours at the Ibero American Library, absorbing Gogol, Tolstoy, Spengler, Hegel, Kant and other great European minds. From these sessions and her own reading, she gradually developed a deep-seated affinity for socialism and the uplifting of the masses. To her in that circle of social climbing students, these two concepts were abstractions for lip service, but she remained a committed and vocal Communist for the rest of her life. She even substituted the 1910 date of the start of the Mexican Revolution for her actual birth year, 1907, as an affirmation of her commitment to revolutionary ideals.

The atmosphere in Mexico City was alive with political debate and danger as volatile speakers stepped forward to challenge whatever regime claimed power only to be gunned down in the street, or absorbed into the corruption. Díaz fell to Francisco Madero who lasted 13 months until he stopped a lethal load of bullets from his general Victoriano Huerta. Populist heroes Francisco “Pancho” Villa and Emiliano Zapata split the country’s peasant population between them, hunting down anyone who disagreed with their land reform manifestos, but neither managed to build a majority and neither was equipped by temperament or education to govern.

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Alicia Galant (detail), 1927. Oil on canvas, 107 x 93.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of My Sister Cristina, 1928. Oil on wood, 99 x 81.5 cm. Collection Otto Atencio Troconis, Caracas.

Venustiano Carranza assumed power as Huerta fled Mexico, and was no better than the lot who had preceded him. All of these politicians were products of Díaz’ Eurocentric economic policies that nurtured the rich and ignored the poor. Into this vacuum were thrust the proletariat ideals of the Communist revolution that had swept Russia following the assassination of the Tzar and his family in 1917. The socialist theories of Marx and Engels looked promising after the slaughter of the seemingly endless Mexican revolution.

And yet, for all this progressive political dialectic and debate, Frida retained some of her mother’s Catholic teachings and – after a satiric flirtation with European dress and attitudes including cross-dressing as a man in a tailored suit – developed a passionate love of all things traditionally Mexican. During this time, her father gave her a set of watercolours and brushes. He often took his paints along with his camera on expeditions and assignments. She began this habit as she accompanied him.

Ten years of revolution had wiped out Mexico’s economy and cost Guillermo Kahlo his job with the government. Matilde sent her servants packing and the quality of life in the Blue House dropped a peg or two as the daughters took over all household chores and Guillermo shouldered his Graflex camera in search of portrait commissions.

With the general population breathing easier under the government of a pair of generals, Alvaro Obregon and Plutarco Calles, some local intellectuals and artists drifted into favour among the government ministries. “Revolutionary” land reforms were pledged. But the same old story prevailed, keeping a fire lit beneath the political debates and burgeoning movements that left the Mexican capitol in constant ferment.

Frida became a casual student at the Preparatory School, enjoying the stimulation of her intellectual friends rather than the formal studies. At age 15, her intellect was sharp and she tested political and philosophical doctrines with her pals in innocent debate where telling points were not measured in death and destruction. During this period, she learned the minister of education had commissioned a large mural to be painted in the Preparatory School courtyard. It was titled Creation and covered 150 square metres of wall. The muralist was the Mexican artist, Diego Rivera, who had been working in Europe for the past 14 years. Assisted by his wife, Guadalupe (Lupe) Marín, and a team of artisans, he assembled scaffolding and the coloured wax that required blow torch heat to fuse to a resin base spread on the charcoal sketched wall grid. This slow encaustic process was eventually abandoned for plaster fresco, but to Frida the creation of the growing scene spreading its way across the blank wall was fascinating. She and some friends often sneaked into the auditorium to watch Rivera work.

His image was far from that of a starving artist. The scaffolding creaked under his weight as he paced back and forth across the wall. Everything about him was oversized from his unruly mop of black hair to the wide belt that held up his pants which sagged in the seat and bagged at the knees. The students nicknamed him Panzón (fat belly).

Eventually these intrusions ended when another group of students, representing the views of their elite ultra-conservative parents, began damaging other murals in progress by the artists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco, claiming the murals promoted atheism and socialist ideology. Rivera’s assistants armed themselves and acted as guards when they were not mixing colours or transferring sketches to the wall. Rivera himself cultivated the image of a revolver-packing defender of creative freedom and often turned up at parties with a big Colt pistol stuffed in his belt or in his jacket pocket.

From a very early age, Frida had been taught by her father to appreciate the art of painting. As part of her education he encouraged her to copy popular prints and drawings of other artists. To ease the financial situation at home, she apprenticed with the engraver, Fernando Fernandez, a friend of her father’s. Fernandez praised her work and gave her time to copy prints and drawings with pen and ink. But she painted with the same enthusiasm as she collected hand-made toys, dolls, and colourfully embroidered costumes – as a hobby, a means of personal expression, not as “art” because she had no thought of becoming a professional artist. She considered the skills of artists such as Diego Rivera far beyond her capabilities. Her earliest works were studies in colours and shapes of buildings such as Have Another One, painted in 1925. It is an aerial view of a town square and has a child’s naïve approach to its flat perspective and the donkey cart making its way across a foreground avenue. Another work, Paisaje Urbano (Urban Landscape), is a composition of architectural planes and linear smokestacks that indicates a more sophisticated structure and an appreciation of the work accomplished by subtle use of shadow and control of values. This application hints at the knowledge gained from her line art copies under Fernandez’ tutelage. It also reflects an eye for composition not unlike the photographs of Edward Weston, who had spent a year in Mexico and was in the process of creating a new way of seeing shapes, textures and their interrelationships. Though she did not consider her painting to be anything but a pleasant pastime, that didn’t stop her from conniving her way into a seat in the auditorium where she watched Rivera work – even under the jealous eye and insults of Lupe Marín. His wife regularly brought Diego his lunch in a basket. It was one way she managed to keep an eye on him, especially when he was painting from a particularly beautiful model. Lupe was his second wife and knew him very well.

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of a Lady in White, c. 1929. Oil on canvas, 119 x 81 cm. Private collection, Germany.

Diego Rivera, Portrait of Señora Doña Evangelina Rivas de Lachica, 1949. Oil on canvas, 198.1 x 139.7 cm. Private collection.

And then everything changed forever. In Kahlo’s words to author, Raquel Tibol:

“The buses in those days were absolutely flimsy; they had started to run and were very successful, but the streetcars were empty. I boarded the bus with Alejandro Gómez Arias and was sitting next to him on the end next to the handrail. Moments later the bus crashed into a streetcar of the Xochimilco Line and the streetcar crushed the bus against the street corner. It was a strange crash, not violent, but dull and slow, and it injured everyone, me much more seriously… I was eighteen then but looked much younger, even younger than (my sister) Cristi who was 11 months younger than I… I was an intelligent young girl but not very practical, in spite of the freedom I’d won. Maybe for that reason I didn’t size up the situation, nor did I have any inkling of the injuries I had… The collision had thrown us forward and the handrail went through me like a sword through a bull. A man saw I was having a tremendous hemorrhage and carried me to a nearby pool hall table until the Red Cross picked me up…”

“As soon as I saw my mother I said to her: ‘I’m still alive and besides I have something to live for and that something is painting’. Because I had to be lying down with a plaster corset that went from the clavicle to the pelvis, my mother made a very funny contrivance that supported the easel I used to hold the sheets of paper. She was the one who thought of making a top to my bed in the Renaissance style, a canopy with a mirror I could look in to use my image as a model.”[1]

The scene of the accident was gruesome. Somehow, the collision tore off Frida’s clothes, dumping her nude onto the shattered floor of the bus. Seated near Frida had been a painter or artisan carrying a paper packet of gold gilt powder. It burst, showering her naked body. The iron handrail had stabbed through her hip and emerged through her vagina. A gout of blood haemorrhaged from her wound, mixing with the gold gilt. In the chaos, bystanders, seeing her bizarre pierced, gilded and blood splashed body began screaming, “La Balarina! La Balarina!” One bystander insisted the hand rail be removed from her. He reached down and tore it from the wound. She screamed so loud the approaching ambulance siren could not be heard.

In 1946, a German physician, Henriette Begun, composed a clinical history of Frida Kahlo. Its entry for September 17, 1925 reads:

“Accident causes fractures of third and fourth lumbar vertebrae, three fractures of pelvis, eleven fractures of the right foot, dislocation of the left elbow, penetrating abdominal wound caused by an iron hand rail entering the left hip, exiting through the vagina and tearing left lip. Acute peritonitis. Cystitis with catheterisation for many days. Three months bed rest in hospital. Spinal fracture not recognised by doctors until Dr. Ortiz Tirado ordered immobilisation with plaster corset for nine months… From then on has had sensation of constant fatigue and at times pain in her backbone and right leg, which now never leaves her.”[2]

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Miguel N. Lira, 1927. Oil on canvas, 99.2 x 67.5 cm. Gabierno del Estado de Tlaxcala, Instituto Tlaxcalteca de Cultura, Museo de Arte de Tlaxcala, Tlaxcala.

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Diego Rivera, 1937. Oil on canvas, 46 x 32 cm. Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, Mexico City.

Letter to Alejandro Gómez Arias

October 20, 1925

According to Dr. Díaz Infante, who treated me at the Red Cross, I’m out of danger now and I’m going to get more or less well. [...] The right side of my pelvis is fractured and deviated, I had a foot dislocation, and a dislocation and small fracture of my left elbow and the wounds that I talked to you about in the other letter: the longest one went through my body from the hip to the crotch, so there were two of them. One has already healed and the other is about two centimetres long by one-and-a-half centimetres deep, but I think it’ll heal soon. My right foot is covered with very deep scratches and another thing is that [...] Dr. Díaz Infante (who is very nice) didn’t want to keep treating me because he says that Coyoacán is very faraway and that he couldn’t leave a wounded person and come when they called him, so he was replaced by Pedro Calderón of Coyoacán. Do you remember him?

Well, since every physician says something different about the same illness, Pedro, of course, said that he thought everything was extremely well except for the arm, and that he doubted very much that I could extend it, because the joint is fine, but the tendon is contracted and keeps me from extending my arm, and if I was able to do it, it would be very slowly and after lots of massages and hot water baths. You can’t imagine how it hurts; every time they pull me I cry a litre of tears, even though they say that you shouldn’t believe in a dog’s lameness or a woman’s tears. My leg hurts so very much, one must think that it is crushed. Besides, the whole leg throbs horribly and I feel very uncomfortable, as you might imagine, but with rest they say that the bone will soon heal and that I’ll be able to walk little by little.

Letter to Alejandro Gómez Arias

January 10, 1927

I am, as always, sick. You see how boring this is. I don’t know what else to do, as I’ve been like this for more than a year and I’m fed up. I have so many complaints, like an old woman! I don’t know what it’s going to be like when I’m thirty years old. You’ll have to wrap me up in a cotton cloth and carry me around all day; I don’t think, as I told you one day, that you could carry me in a bag, because I just won’t fit in it. [...] I need you to tell me something new because truly I was born to be a flower pot and I never leave the dining room. I’m buten buten bored!!!!!! You’ll say that I should do something useful, etc., but I don’t feel like it. I don’t feel like doing anything – you know that already, and that’s why I don’t explain it to you. I dream of this room every night, and no matter how I try, I don’t even know how to erase that image from my head (which, besides looks more like a bazaar everyday). Well! What can we do about it? Wait and wait... [...] I, who dreamed so many times of being a navigator or a traveller! Patiño would answer that it is one of the ironies of life. Ha ha ha ha! (Don’t laugh). But it’s only been seventeen years that I’ve been parked in this town. Later, I will surely be able to say, “I’m just passing through; I don’t have time to talk to you”. [Here she drew musical notes.] Well, after all, visiting China, India, and other countries comes second... Firstly, when are you coming? I don’t think I will need to send you a telegram telling you that I’m in agony, will I; [...] Hey, ask among your acquaintances whether someone knows a good way to lighten hair; don’t forget to do it.

Frida Kahlo, Thinking about Death, 1943. Oil on canvas, mounted on masonite, 44.5 x 36.3 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

Diego Rivera, Self-Portrait, 1906. Oil on canvas, 55 x 54 cm. Collection of the Government of the State of Sinaloa, Mexico City.

Death of Innocence

The devastation to Frida Kahlo’s body can only be imagined, but its implications were far worse once she realised she would survive. This vital vivacious young girl on the brink of any number of career possibilities had been reduced to a bed-bound invalid.

Only her youth and vitality saved her life, but what kind of life did she face? Her father’s ability to earn enough money to feed his family and pay Frida’s medical bills had diminished with the Mexican economy. This necessitated lengthening her stay in the overburdened, undermanned Red Cross hospital for a month.

“The Red Cross Hospital was very poor. We were kept in a kind of tremendous slave quarters, and the meals were so vile they could hardly be eaten. One lone nurse took care of 25 patients.”[3]

After being pinned to her bed, swathed in plaster and bandages, she was eventually allowed to go home to La Casa Azul. Being away from her friends in Mexico City, she penned a voluminous correspondence to them and especially to Alejandro Gómez Arias.

Their sexual relationship ended prior to the accident and they had agreed each could see other people.

When they met as “friends” however, Frida shrugged off Alejandro’s boasts of female conquests. But he became sullen when she ticked off the young men she had bedded. They were too much alike.

While she was recuperating from the accident, Alejandro’s parents sent him to Europe and to study in Berlin. The long separation and worldly adventure considerably cooled what ardour remained in him for the small town Mexican girl he left behind.

Frida, conversely, kept up a flurry of letters filled with pitiful longing to see him as she lay in her plaster prison.

“When you come I won’t be able to offer you anything you’d want. Instead of having short hair and being a flirt, I’ll only have short hair and be useless, which is worse.”

“All these things are a constant torment. All of life is in you, but I can’t have it… I’m very foolish and suffering much more than I should.”

“I’m quite young and it is possible for me to be healed, only I can’t believe it; I shouldn’t believe it, should I? You’ll surely come in November.”[4]

Gradually, her indomitable will asserted itself and she began to make decisions within the narrow view she commanded.

By December, 1925, she regained the use of her legs. One of her first painful journeys was to Mexico City and the home of Alejandro Gómez Arias just before Christmas. She waited outside his door, but he never came out to meet her.

Shortly thereafter, she was felled by shooting pains in her back and more doctors trooped into her life.

Her three undiagnosed spinal fractures were discovered and she was immediately encased in plaster once again.

Trapped and immobilised after those brief days of freedom, she began realistically narrowing her options. At the Preparatory School she had begun studies that would lead to a career in medicine. That dream faded when she accepted her physical limitations.

As days of soul searching continued, she passed the time painting scenes from Coyoacán, and portraits of relatives and her friends who came to visit.

As an artist, she only visited the scene of her accident once in a pencil drawing that showed her bandaged body with the small bus and the trolley car crushed together against the corner of the market building.

It was a cathartic drawing, pulled from her imagination and the testimony of others. How many times in her dreams and day dreams had she stood apart from that terrible scene before she drew it – and then left it unfinished?

The praise her paintings elicited surprised her and she began deciding who would receive the painting before she started it – often writing the name of the recipient on the canvas.

She gave them away as keepsakes, assigning them no value except as tokens of her feelings. Of these early efforts, her best portraits succeeded in reaching beneath the skin of the sitter and stood alone and original without technical tricks, or imposed sentiment.

Her most successful work was a self-portrait, painted specifically for Alejandro Gómez Arias in yet another vain attempt to win him back.

With this painting, she began a remarkable lifetime series of fully realised Frida Kahlo reflections, both introspective and revealing, that examined her world from behind her own eyes and from within that crumbling patchwork of a body. Officially titled Self-Portrait with Velvet Dress, her 1926 gift to Alejandro was named, “Your Botticeli” (sic).

While on his tour of Europe, Arias had mentioned that Italian girls were “so exquisite, they look like they were painted by Botticelli”.

Frida added some of the elegant mannerisms of the sixteenth-century painter, Bronzino (1503-1572), a favourite of hers. In the portrait she holds her hand open to Arias, a possible desire for reconciliation.

Her skin glows with an ivory cast and the blush of health in her cheeks, not the pasty face of a surrendering invalid. Her gaze is direct and challenging beneath her exaggerated single eyebrow.

Frida Kahlo, Girl in Diaper (Portrait of Isolda Pinedo Kahlo), 1929. Oil on canvas, 65.5 x 44 cm. Private collection.

Diego Rivera, Delfina and Dimas, date unknown. Oil on canvas, 31 x 24 cm. Private collection.

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Eva Frederick, 1931. Oil on canvas, 63 x 46 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

What she gives away with her open Bronzino hand, she takes back with the defiance of a survivor. This stoic, examining and unsmiling gaze is the pose that she adopted in real life.

As if to add a period to her message, across the bottom of the canvas she wrote:

“For Alex, Frida Kahlo, at the age of 17, September 1926 – Coyoacán – Heute Ist immer noch (Today is like always).”

In other words, she is saying “If you ever did love me, then today is like always and that love is still there”. Frida Kahlo consistently maintained her own demanding reality that no one, not even Diego Rivera, ever succeeded in penetrating to its steel core.

Through 1927 and 1928, Frida painted portraits of those close to her. She captured the glacial beauty of her friend, Alicia Galant.

Frida’s younger sister, Cristina, is rendered in shimmering pastel tints that surround a sharply executed and resolute face. Frida painted her toddler niece, Isolda Pinedo Kahlo as cotton soft with the child’s favourite doll lying ignored at her feet, but with roaming eyes looking for escape from the boredom of sitting.

With each painting, Frida’s confidence grew along with her technical facility.

The diminished state of her relationship with Alejandro Gómez Arias is obvious in her 1928 portrait of him. He looks like a school boy in his first grown-up suit. His expression is haunted and unsure.

The boy in the painting has either missed a great opportunity and is completely unaware – or, more likely, he has dodged a passionate, all-consuming bullet and is relieved. As with almost all the men in her life, he remained a close friend, held in her orbit by the mutual fascination that first drew them together.

By 1928, Frida had recovered enough to set aside her orthopaedic corsets and escape the narrow world of her bed to walk out of La Casa Azul once again into the social and political stew that was Mexico City.

She began re-exploring the heady world of Mexican art and politics. She wasted no time in hooking up with her old comrades from the various cliques at the Preparatory School. Soon, as she drifted from one circle to another, she fell in with a collection of aspiring politicians, anarchists and Communists who gravitated around the American expatriate, Tina Modotti.

Tina was a beautiful woman who came to Mexico in 1923 to study photography with her lover, the artistically ascetic American photographer Edward Weston. When he returned to California in 1924, she remained behind to begin a short storied life as an excellent photographer in her own right and companion to an assortment of revolutionaries.

During the First World War and the early 1920s, many American intellectuals, artists, poets and writers fled the United States to Mexico and later to France in search of cheap living and political idealism. They banded together to praise or condemn each other’s works and drafted windy manifestos while participating in one long inebriated party that lasted several years, lurching from apartment to salon to saloon and back.

Frida Kahlo, The Bus, 1929. Oil on canvas, 25.8 x 55.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

While most were a motley collection of exiles who skipped across the border just ahead of bankruptcy and bad debts, some genuine talents added their luster to Mexican society. John Dos Passos lived for some periods in Mexico City as did Katherine Anne Porter and poet Hart Crane.[5]

These expatriates fashioned a sentimental vision of the noble peasant toiling in the fields and promoted the Mexican view of life as fiestas y siestas interrupted by the occasional bloody peasant revolt and a scattering of political assassinations.

Into this tequila-fueled debating society stepped the formidable presence of Diego Rivera, the prodigal returned home from 14 years abroad and having been kicked out of Moscow. Despite his rude treatment at the hands of Stalinist art critics and the Russian government’s unveiled threats of harm if he did not leave, Diego embraced Communism as the world’s salvation.

Soon after his return to Mexico in 1921, he sought out pro-Mexican art movements, Mexican muralists and easel painters, photographers, and writers.

Within this deeply Mexicanistic society, Tina Modotti’s circle of expatriates and fellow travellers fit right in to the party circuit. Diego also went to work on another series of murals for the government ministry of education.

Frida drifted into this stimulating circle. She and Tina Modotti became friends. Possessing similar incendiary personalities and sensual vitality, they drank and danced deep into the hot Mexican nights at the moveable salons. In the sweltering rooms, crowded with drunken eccentrics and oblivious hangers-on, political rhetoric or denunciations of artistic merit often took on an edge.

Challenges sometimes required redress by gunplay. Gulping down a quart of tequila did not enhance marksmanship and usually, when the smoke cleared, the only casualties were the furniture, walls, streetlamps and at one particular salon, a record player. As Frida recalled her first meeting with her future husband:

“We got to know each other at a time when everybody was packing pistols; when they felt like it, they simply shot up the street lamps in Avenida Madero. Diego once shot a gramophone at one of Tina’s parties. That was when I began to be interested in him although I was also afraid of him.”[6]

So, the small and still physically frail Frida Kahlo had a chance to see old soft Panzón in a different light, gripping a smoking Colt revolver in a crowded room suddenly fallen silent.

The chubby muralist had hidden layers to him as well as a manly set of cojones. And Diego saw the same flash in the school girl who had stood eye to eye with his now ex-wife, Lupe Marín, and held her ground.

This was more than a spoiled child of the bourgeoisie who smiled back at him through the cigar smoke, punctuating her intelligent vocabulary with vulgar street slang for effect. She challenged him and Diego Rivera, ever the swordsman, never refused a challenge.

Diego Rivera, Artist’s Studio, 1954. Oil on canvas, 179 x 150 cm. Collection Acervo Patrimonial de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, Mexico.

Frida Kahlo, Ex voto, c. 1943. Oil on metal, 19.1 x 24.1 cm. Private collection.

The actual point of their first meeting is difficult to discover since they were both elaborate story tellers who often bent the truth to fit the moment.

There’s a charming tale that has Frida rising from her bed, tucking some of her work under her arm and hobbling with a cane to where Diego worked on the ministry of education murals. She calls to him high on the scaffolding:

“Diego, come down!”

He peers into the courtyard at this young girl wearing a blue and white European school costume, long braids and leaning on a cane. It was his curse to be easily distracted from his work so he lumbers down the rickety stairs.

“But I haven’t come here to flirt”, she says, “even though you’re a notorious ladies’ man. I just want to show you my pictures. If you find them interesting, tell me; if not, tell me anyway because then I’ll find something else to do to support my family”.

The big man with the shaggy head of hair and paint-smeared apron wrapped around his girth looks at each painting. He separates one from the other three and looks at it for a longer time.

“First of all, I like the self-portrait. That is original. The other three pictures seem to have been influenced by things you must have seen somewhere. Now, go home and paint another picture. Next Sunday I’ll come and tell you what I think of it”.

Frida finishes her tale, “He did just that and concluded that I was talented”.[7]

If this romantic story is to be believed, Diego Rivera concluded more than the depth of her talent. His original interest in the cheeky young girl, whose feisty attitude had charmed him, turned to a deeper respect, an appreciation of her as a fellow artist to whom he could relate on many different levels.

It wasn’t long before he dusted off his brown Stetson hat, shook out his sagging jacket, polished the toes of his boots on the backs of his pant legs and began showing up at La Casa Azul every Sunday.

Diego had become a courting suitor. Frida’s mother was against the match. She likened Diego to a big toad standing in the doorway. Guillermo Kahlo took Diego aside, steering him into the central courtyard.

Diego may have looked like a fat toad. He may have been twenty years her senior. He was divorced – twice – and an atheist, and a Communist to boot, but he was also a famous painter who had commissions and money and the respect of both the government and the artistic community to which Guillermo Kahlo aspired.

Guillermo leaned close. “Do you realise she’s a little devil?”

Diego nodded, “I know”.

Guillermo made a final appeal, “She is a sick person and all her life she will be sick. She is intelligent, but not pretty. Think it over if you want, and if you wish to get married, I give you my permission”.

Diego nodded again, “Gracias”.

Guillermo nodded. “All right, you’ve been warned”.[8]

Frida Kahlo, Tree of Hope, Keep Strong, 1946. Oil on masonite, 55.9 x 40.6 cm. Isidore Ducasse Collection, France.

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Lucha Maria, a girl from Tehuacán, (Sun and moon), 1942. Oil on masonite, 54.6 x 43.1 cm. Private collection.

Letter to Alejandro Gómez Arias

May 31, 1927

I’m almost finished with Chong Lee [Miguel Lira]’s portrait; I’m going to send you a photograph of it. [...] This gets worse and worse every day. I’ll have to convince myself that it is necessary, almost for sure, to be operated on. Otherwise, time goes by and suddenly you’ve wasted a hundred pesos, given away to a pair of thieves – that’s what most doctors are. The pain continues exactly the same in my bad leg and sometimes the good one hurts too; so I’m getting worse and worse, and without the least hope of getting better, because for that I need the most important thing: money. The sciatic nerve is damaged, as well as another nerve – whose name I don’t know – that branches into the genitals. I don’t know what’s wrong with two vertebrae and there’s buten other things that I can’t explain to you because I don’t understand them myself, so I don’t know what the operation will consist of, since nobody can explain it. You can imagine, from what I am telling you, the hope I have of being, if not well, at least better, by the time you arrive. I understand that it is necessary in this case to have a lot of faith, but you can’t imagine, not even for a moment, how much I suffer with this, precisely because I don’t think I’m going to recover. A doctor with some interest in me could possibly make me feel better, at least, but all these doctors who have been treating me are meanies who don’t care about me at all and who spend their time stealing. So I don’t know what to do and to despair is useless. [...] Lupe Vélez is shooting her first movie with Douglas Fairbanks, did you know that? How are the movie theatres in Germany? What other things about painting have you learned and seen? Are you going to go to Paris? How is the Rhine; German architecture? Everything.

Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column, 1944. Oil on masonite, 39 x 30.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkey, 1938. Oil on masonite, 49.5 x 39.4 cm. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo (New York).

Letter to Alejandro Gómez Arias

July 23, 1927

My Alex:

I just received your letter…You tell me that you will be taking a boat to Naples and that it is almost certain that you will go to Switzerland too. Let me ask you a favour: tell your aunt that you want to come back, that you don’t want to stay there after August under any circumstances... you can’t imagine what every day, every minute without you means to me...

Cristina [her younger sister] is still very pretty, but she is very mean to me and to my mother.

I did a portrait of Lira because he asked me to, but it is so bad that I don’t understand how he can tell me that he likes it. Buten horrible. I am not sending you the photograph since my dad doesn’t have all the plates in order yet because of the move; but it’s not worth it, since it has a very corny background and he looks like a cardboard figure. I only like one detail (one angel in the background), you’ll see it. My dad also took pictures of the others, of Adnana, of Alicia [Galant] with the veil (very bad), and of the one who aimed to be Ruth Quintanilla and that Salas likes. As soon as my dad makes me more copies I will send them to you. He only made one of each, but Lira took them away, because he says he is going to publish them in a magazine that is going into circulation in August (he must have already talked to you about it, hasn’t he?). It will be named Panorama, and the contributors for the first issue will be, among others, Diego, Montenegro (as a poet), and who knows how many others. I don’t think it will be anything very good. I already tore up Rios’s portrait, because you can’t imagine how it still annoyed me. Flaquer wanted to keep the backdrop (the woman and the trees) and the portrait ended its life as Joan of Arc did. Tomorrow is Cristina’s saint’s day. The boys are going to come over and so are the two children of Mr Cabrera, the lawyer. They don’t look like him (they are very stupid) and they barely speak Spanish, because they have lived in the United States for twelve years and they only come to Mexico for vacations. The Galants will come too, la Pinocha [Esperanza Ordonez], etc... Only Chelo Navarro is not coming as she’s still in bed because of her baby girl; they say she’s very cute. This is all that is going on in my house, but none of this interests me.

Tomorrow it will be a month and a half since I got the cast, and four months since I last saw you. I wish that next month life would start and I could kiss you. Will this come true?

Your sister,

Frieda

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with “Bonito”, 1942. Oil on canvas, 55 x 43.5 cm. Private collection.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkey and Parrot, 1942. Oil on masonite, 54.6 x 43.2 cm. Private collection.

Letter to Alejandro Gómez Arias

April 31 [1927], Sunday Labour Day

My Alex,

I just got your letter of the 13th, and this has been the only happy moment in all this time. Even though thinking of you always helps me to feel less sad, your letters help even more. How I wish I could explain to you, minute by minute, my suffering. Since you left, I’ve gotten worse and I cannot for a moment either console myself or forget you. Friday, they put the plaster cast on me, and since then it’s been a real martyrdom that is not comparable to anything else. I feel suffocated, my lungs and my whole back hurt terribly; I can’t even touch my leg. I can hardly walk, let alone sleep. Imagine, they hung me by just my head for two and a half hours, and then I stood on my tiptoes for more than one hour while [the cast] was dried with hot air; but when I got home, it was still completely wet.

They put it on me at the Hospital de las Damas Francesas, because at the Hospital Frances it would have been necessary to stay at least a week, as they wouldn’t do it otherwise. At the other hospital they started to put it on me at 9:15 A.M. and I was able to leave at approximately 1 P.M. They didn’t let Adriana [her sister] or anybody else in, and I was suffering horribly, all by myself. I’m going to have this martyrdom for three or four months, and if I don’t get well with that, I sincerely want to die, because I can’t stand it anymore. It’s not only the physical suffering, but also that I don’t have the least entertainment. I never leave this room, I can’t do anything, I can’t walk. I’m completely desperate and, above all, you’re not here. On top of that, I only hear bad news. My mother is still very sick, she’s had seven strokes this month, and my father is the same, and broke. There’s something to be completely desperate about, don’t you think? I lose weight every day, and nothing amuses me anymore. The only thing that makes me happy is that the boys visit me; last Thursday Chong, el Güero Garay, Salas, and Goch came, and they’re going to come back on Wednesday. Nevertheless, this makes me suffer too because you’re not with us.

Your little sister and your mum are doing well, but I’m sure they would give anything to have you here; do everything you can to come back soon. Don’t doubt, even for a moment, that I’ll be exactly the same person when you come back. And you – don’t forget me and write to me a lot. I look forward to getting your letters almost with anguish; they make me feel infinitely well.

Never stop writing to me, at least once a week; you promised. Tell me if I can write to you at the Mexican Legation in Berlin or at the same place as always. I need you so much, Alex! [water sign as signature]

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait wearing a Velvet Dress (detail), 1926. Oil on canvas, 12.5 x 17 cm. Museo Frida Kahlo, Mexico City.

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Engineer Eduardo Morillo, date unknown. Oil on masonite, 39.5 x 29.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

Letter to Guillermo Kablo

San Francisco, Cal. November 21, 1930

Lovely Daddy,

If you knew the pleasure getting your little letter gave me, you’d write to me every day, because you can’t imagine how happy it made me. The only thing I didn’t like is that you told me that you are still quick-tempered, but since I am just like you, I understand you very well, and I know that it is very hard to control oneself. Anyway, try as hard as you can; at least do it for mum who is so nice to you. Diego laughed really hard at what you told me about the Chinese, but he says he will take care of me so they won’t kidnap me. I am well, under [a treatment of] injections by a certain Dr. Eloesser, who is of German origin but speaks Spanish better than someone from Madrid, so I can clearly explain to him everything I feel. I’m learning a little bit of English every day, and I can at least understand the essentials, shop at stores, etc., etc…

Tell me in your reply how you are and how mum and everybody are doing. I miss you very much – you know how much I love you – but certainly in March we will be together again and we will talk a whole lot. Don’t fail to write me and feel free to let me know if you need some money. Diego sends his warmest wishes and says that he doesn’t write to you because he has so much to do.

I send you all my affection and a thousand kisses. Your daughter who adores you, Frieducha

Here is a kiss

Write to me everything you do and everything that happens to you

Señora Diego Rivera

On August 21, 1929, Frida Kahlo, age 22, married Diego Rivera, age 42, in a civil ceremony, joined by a few close friends at the Coyoacán City Hall. Looking on as official witnesses were a homeopathic doctor and a wig maker. The judge was a pal of Rivera’s from his student days at the School of Fine Arts.

Diego, his hair slicked back, stood up in a plain grey suit, his Stetson hat, wide belt and the Colt revolver in his waistband. Frida had borrowed a long skirt and blouse from her maid and wore a red reboso stole over her shoulders.

She barely came up to his shoulder, giving the couple the appearance of a small dark china doll next to an immense porcelain pug dog. After the ceremony they posed for a photographer from La Prensa. The accompanying story read:

“Last Wednesday in the nearby village of Coyaocan, the controversial painter Diego Rivera was married to Miss Frida (sic) Kahlo, one of his students. The bride was dressed, as can be seen, in simple street garb, and the painter Rivera as an American without a vest.”

“The marriage was not at all pompous, but carried out in an extremely cordial atmosphere with all modesty, without ostentation and minus ceremonious pretentiousness. The newlyweds were extensively congratulated after the marriage by some intimate friends.”

And then the party shifted to La Casa Azul. Matilde Kahlo still fumed, muttering that Rivera now looked like a “fat farmer” – an improvement over the “fat toad”. Lupe Marín had also been invited and after a liberal sampling of tequila thrust her hands under Frida’s dress and hauled it up.

“Do you see those two canes?” Marín screeched. “That’s what Diego’s going to have to put up with and he used to have my legs!” She hoisted her own skirt, showing off her shapely gams for comparison. Frida made a grab for her. Friends restrained the two women and Frida bolted from the room in a fury. Diego, of course, was delighted to see two women he had bedded and wedded fighting over him and to celebrate the occasion headed for the bar.

His gay mood continued into the wee hours whereupon he drew his trusty Colt revolver and, aiming through a boozy fog, began blazing away. Guests sought cover until the pistol’s hammer clicked empty on spent cartridges.

Frida was fuming and did not spend the night with him. In fact she didn’t move into his house at 104 Paseo de la Reforma for several days.[9]

Though not known at the time, this wedding and its aftermath would be a microcosm of the rest of their lives together.

Señora Rivera began setting up housekeeping in his house as Diego was appointed director of the San Carlos Academy, his youthful alma mater.

Within a couple of weeks Diego’s reforms of the school’s curriculum met with a sour reception and he was summarily requested to leave the campus.

At that time, he accepted a commission to create a series of murals in the National Palace which were to form a visual history of Mexico.

The job was huge and he returned to it many times over the following years. It required five years just to complete the stairwell. The palace courtyard mural wasn’t begun until 1942.

Continuing in her role as the good wife, Frida reconciled with Lupe Marín who showed her how to prepare Diego’s favourite mole, rich puddings and other dishes that kept up his energy during ten to twelve hour work days. As Lupe had done, Frida brought Rivera his lunch at the scaffolding each day.

With her duties as Rivera’s doting wife claiming more of her time, she virtually stopped painting. In 1929, however, she did manage to creatively put her psychological house in order.

One canvas seems to mark a step in distancing herself from the cause of her physical turmoil. She painted The Bus.