Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

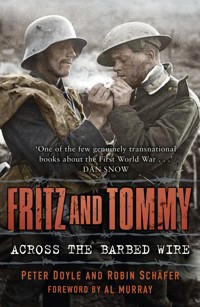

It was a war that shaped the modern world, fought on five continents, claiming the lives of ten million people. Two great nations met each other on the field of battle for the first time. But were they so very different? For the first time, and drawing widely on archive material in the form of original letters and diaries, Peter Doyle and Robin Schäfer bring together the two sides, 'Fritz' and 'Tommy', to examine cultural and military nuances that have until now been left untouched: their approaches to war, their lives at the front, their greatest fears and their hopes for the future. The soldiers on both sides went to war with high ideals; they experienced horror and misery, but also comradeship/Kameradschaft. And with increasing alienation from the people at home, they drew closer together, 'the Hun' transformed into 'good old Jerry' by the war's end. This unique collaboration is a refreshing yet touching examination of how little truly divided the men on either side of no-man'sland during the First World War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 484

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Für unsere Eltern

The Great War has always been a story about two opposing sides. Here in the pages of Fritz and Tommy we at last have that story, told in stark relief and in a meaningful and often very moving way. In nearly forty years of reading about the Great War this is arguably one of the most important books I have come across. It is simply essential reading for anyone with an interest in World War One.

PAUL REED, HISTORIAN

Fritz and Tommy ingeniously unpicks the traditional straitjacket of ‘national memory’ in World War One by using diaries and letters home to show both the similarities and the differences between British and German soldiers. Engaging, poignant and hugely informative, it is an inspired concept, brilliantly executed.

ROGER MOORHOUSE, HISTORIANANDAUTHOROFTHE DEVILS’ ALLIANCE: HITLER’S PACTWITH STALIN, 1939-1941

In this excellent book Peter Doyle and Robin Schäfer weave together personal testimony, memoirs and contemporary writing to illustrate the contrasts, similarities and shared experience of British and German soldiers on the Western Front. The result is a fascinating, thought-provoking and frequently touching story of men at war.

SPENCER JONES, MILITARYHISTORIANANDAUTHOROFCOURAGEWITHOUT GLORY: THE BRITISH ARMYONTHE WESTERN FRONT 1915

This is a wonderful account of the day-to-day lives of the British and German soldiers who fought the Great War. It cuts through the gloss of a hundred years of distortion and propaganda to reveal the faces of the real men who lived and died in the mud and blood of the trenches.

GILES MACDONOGH, HISTORIANANDAUTHOROFAFTERTHE REICH

Fritz and Tommy is a triumph. A time machine. Open it, step inside, and you are back in that hot distant summer of 1914. Travel with the combatants as they scribble their letters from those opening days of the war, to the shattered rubble of fallen empires and devastated landscapes of 1918. The young men are long gone. In this remarkable book they live again. Sit with them. Hear their tales.

MAJOR NIGEL PRICE, EX-7TH GURKHA RIFLES, AS ‘ANTHONY CONWAY’, AUTHOROFTHE CASPASIANNOVELSANDTHE MOON TREE

This remarkable book is a fitting memorial to the men and women of both nations who served in the Great War.

LORD FAULKNEROF WORCESTER, CHAIRMANOFTHE ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY WAR HERITAGE GROUP

When it is peace, then we may view again

With new-won eyes each other’s truer form

And wonder. Grown more loving-kind and warm

We’ll grasp firm hands and laugh at the old pain,

When it is peace. But until peace, the storm

The darkness and the thunder and the rain.

CAPT. CHARLES HAMILTON SORLEY

KILLEDIN ACTION, LOOS, 13 OCTOBER 1915

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all those who contributed to our work – directly or indirectly. Petra Schuir, Werner Kodorra and Wilhelm Himmes allowed us to make use of their extensive collections of German wartime letters and diaries. Individuals gave us access to precious family diaries in their care: Kate and Gill Hutchinson for the moving letters and diaries of William Taffs, killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme; Andy Nurse, custodian of the diaries of Pte J.H. Benn; Kenneth Bone for the 1914 diary of Pte H.W. Talbot; Paul Rodger for access to his grandfather Sgt J. Compton’s diary; Martin Howard for his grandfather Cpl Albert Howard’s diary; and Pete Whitehead for his grandfather Pte Philip Whitehead’s diary.

We thank Giles MacDonogh for allowing us to use his translations of German wartime poetry, and Vanessa Domizlaff, great-granddaughter of Feld-Oberpostmeister Georg Domizlaff, commander-in-chief of the German Field Post Service during the First World War, for help with the transcription of German handwriting of the period. Paul Reed is thanked for his help, advice and enthusiasm for the project; Nick Britten, Stuart Disbrey, Mike Edwards, Chris Foster, Taff Gillingham, Wytzia Raspe, Horst Schäfer, Maximilian Seidler and Julian Walker also assisted us with wise words, advice and support. Jo de Vries at The History Press gave unflinching support and unequalled enthusiasm for the book at all its stages.

Contents

Title

Dedications

Quote

Acknowledgements

Foreword/

Vorwort

by Al Murray

Introduction/

Einführung

1 The Armies/

Die Armeen

2 In the Field/

Im Feld

3 Morale/

Die Moral

4 Battle/

Die Schlacht

5 Wounds and Death/

Verwundung und Tod

6 Blighty/

Die Heimat

Postscript: The Men

Bibliography

Copyright

Foreword/Vorwort

The First World War, as anyone sensible will tell you, is the event that birthed the modern world, that set the twentieth century’s tumultuous events in motion, that unleashed the forces that devastated the world as empires collapsed and new ones rose. While this all might be true, you might also say it’s somewhat impersonal. The First World War wasn’t about tectonic plates grinding against one another so much as ordinary men facing each other across no-man’s-land in countless battlefields all over the world, in a war that both sides saw as a war for survival.

Peter and Rob – Tommy and Fritz, respectively – have done what many have been unable to do in the wake of the First World War’s centenary, and put aside the whoever and, dare I say, the whatever about how the war began, and looked at those ordinary men and their attitudes. Diaries, letters home, written without the benefit of hindsight, without the outcome or the terrible butcher’s bill at the end of the war in mind.

‘Fritz and Tommy’ came from countries you might be tempted to describe as ‘the same but different’. Their armies had their own powerful traditions, and had spent the decades running up to the outbreak of war admiring each other and comparing themselves. When war came, both institutions were sorely tested by the deadlock that followed – the personal accounts in Fritz and Tommy take us into these challenges – and German and British soldiers continued to admire and compare as much as they were told to hate each other.

As the First World War becomes more distant in time, and the ancient animosities fade, a book like Fritz and Tommy helps to peel another layer from the historical onion. There’s lots to learn from this book, and maybe some of the glib answers about the First World War will be replaced by sterner questions. Why do men fight? And why, even when things are as bad as they were, do they continue to fight?

Al Murray

Introduction/Einführung

You have to know that in some places our trench is only 15 metres away from the enemy. You won’t believe it, but last night a Tommy called us in German! Haben Sie Zigarren? One of my men threw some over the parapet and they seemed to have reached their destination as a few minutes later something landed in our trench. First we thought it was a grenade, but it turned out to be a small metal tin full of chocolates! After that there was silence. The English are a lot different to the French. I will send you the tin as it is quite decorative! Has Werner been promoted yet? I hope to meet him in Cologne soon …

LEUTNANT WALTER BLUMSCHEIN, 3 FEBRUARY 1916

There has been no firing here today as far as I know as Fritz seems to be quite as sentimental as we are over Christmas. It is nice to feel that this awful war is so contrary to the spirit of Christ that they try and stop it on His Birthday. Why they don’t attempt to do so every day beats me.

RFN WILLIAM C. TAFFS, 1/16TH QUEEN’S WESTMINSTER RIFLES, 26 DECEMBER 1915

Fritz and Tommy. Two protagonists in a war that claimed over 10 million military lives and that was fought on five continents. Who were they? What drove them to fight? And what was it like for them both, separated by lines of trenches and fields of cruelly-barbed wire?

The First World War/der1. Weltkrieg, defined Europe. While it is true that the wars of European liberation and confederation that erupted each decade of the late nineteenth century created new nation states, the Great War was a conflict that shaped the continent we know today. Old empires fell, monarchies were toppled, new nations created. From the ruins of a Europe wracked by two world wars arose the vibrant confederation we know today. But with the causes, effects and grand strategies of the war discussed now – a hundred years on – with renewed vigour, there is also a human story.

The British saw almost 900,000 military deaths during the First World War, and the Germans more than twice this, at over 2 million (and with some 750,000 civilians dead through malnutrition): 2 per cent of the British population, 4 per cent of the German one. Add to this the millions who returned home with memories, wounded, maimed and mentally scarred – the war left an indelible mark on both countries. As we personally reflect upon these figures we can think of our forebears: Wehrmann Peter Gilgenbach, wounded on the Marne in September 1914; Pte William Black, killed at Bellewaarde in Flanders in 1915; Pte Thomas Roberts, killed in action at Passchendaele in August 1917, Pte Albert Howard, who died of wounds at Arras in October 1918, aged just 18; or brothers Joseph and August Reinhardt who were both killed near Luxemont-et-Villotte within just two days of each other. Framing experiences in this way we can consider the lives of these men as they faced their enemies across the barbed wire, and those of their extended families – the shared experience of humanity.

More than 100 years have passed since the war broke onto the world stage in June 1914. Over this century, and clouded by the impact of another, even more terrible conflict, the origins of the Great War and the nature of its battles and leaders have been much discussed. Almost before the war’s end, books and articles sought to address the balance of war guilt, and consider accusations of incompetence by leaders. Yet above this climate of accusation and counter-accusation, there remains a simple truth – that soldiers on both sides believed in the cause they were fighting for. They fought to protect their homes, their families, and their way of life. They fought for King and Country/für König und Vaterland, and they believed that God was on their side/Gott mit uns.

In 1916, the famous novelist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote of the soldiers of 1914. In Britain, he recalled, ‘A just war seemed to touch the land with some magic wand, which healed all dissensions and merged into one national whole …’, while the German soldiers ‘were filled with patriotic ardour and a real conviction that they were protecting their beloved Fatherland. One could not but admire their self-sacrificing devotion.’ Although as the war dragged on, the appetite for war lessened – particularly in Germany, with many soldiers calling for a compromise peace – those men who marched home in 1918, and who had seen such sacrifices, did so with pride. With no old soldiers of the conflict left to express this view, our task is to interpret what they left behind, their letters, writings and interviews. And drilling down deeply into these, we find the experience of the front-line soldiers, those men who endured life ‘in the trenches’.

For most people, trench warfare is the First World War. Though the war extended across four continents, from the wet Flanders Plain to the steppes of Russia, from the deserts of the Middle East to the Alps, life ‘in the trenches’, as depicted in France and Belgium, continues to fascinate. Assisted by numerous sharply focused photographic images, the perception of life in the Great War is one of men and animals struggling to survive, making the best of a life of utter squalor before being sent ‘over the top’ in large set-piece battles. These views endure, informed not only by the rich photography, but also by the legacy of war art, literature and poetry that came pouring out in the ten-year period after the war’s end. Tellingly, for the most part these stories have been from the Allied side, the victors, and the life of the average Imperial German soldier overshadowed by events forged when the Treaty of Versailles was signed in June 1919.

The war between Fritz and Tommy commenced once the British Expeditionary Force, landing in France in early August, took up its pre-determined position in the line in support of the French. Arriving on the continent, the British soldiers were taken in by the sights, sounds and smells, the waving crowds and the strange accents. Regulars – many of the British troops had experienced the rigours of international duties, and had acted as guardians of Empire in far-flung outposts, across India, in Africa, the Caribbean and even the Mediterranean – they were used to foreign postings; after all, over half the British army of 1914 was spread overseas. And they were well trained. In the aftermath of the disastrous opening campaigns of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902, when the Boer citizen-soldiers had painfully exposed the inadequacies of the British regular army, things had been tightened up considerably. New manuals were developed, insistence on adequate musketry training increased, and all arms were trained to a high degree to meet their responsibilities as international policemen of Empire. And yet, that next foe would be one of the most highly organised, efficient and powerful of European nations – one that had been described in the British press just seventeen years previously as ‘a perfect machine’, a machine only too capable of defeating Britain on the field of battle:

The German Army is the most perfectly adapted, perfectly running machine. Never can there have been a more signal triumph of organisation over complexity. The armies of other nations are not so completely organised. The German Army is the finest thing of its kind in the world; it is the finest thing in Germany of any kind. Briefly, the difference between the German and, for instance, the English armies is a simple one. The German Army is organised with a view to war, with the cold, hard, practical, business-like purpose of winning victories. And what should we ever do if 100,000 of this kind of army got loose in England?

G.W. STEEVENS, DAILY MAIL, 1897

The first British soldiers to be captured in 1914 saw for themselves the power of their enemies:

Once we passed a train with heavy artillery on specially constructed wagons, and we saw several trains of ordinary field artillery. These trains of troops, munitions, motor-cars, coal, and a hundred other weapons of war that were hidden from view, the whole methodical procession of supplies to the Front, were most suggestive of power, of concentration, and organisation of effort. Most impressive was this glimpse of Germany at war. It is difficult to convey the impression to those who have not seen Germany in a state of war. Men who have been at the Front see little of the power which is behind the machine against which they are fighting.

LT MALCOLM VIVIAN HAY, 1ST GORDON HIGHLANDERS, 1914

In summer 1914, the German army in the west stood at about 1.6 million strong. This machine, programmed to win, swept through the borders of Belgium as it took its part in unleashing the Schlieffen Plan, the German war plan that had been developed in 1904. With a wary eye on revenge-hungry French to the west – allied to the Russians in the east – the plan envisaged a great arcing movement that would involve seven armies wheeling around, constrained only by the Channel coast. The plan demanded that the German armies pass with speed through the low countries. No delays could be tolerated, and no resistance from civilians allowed. In August 1914, any who stood in their way were dealt with, summarily, and the Germans marched on, their sights set on the encirclement of Paris:

I had just declared in the Reichstag that only dire necessity, only the struggle for existence, compelled Germany to march through Belgium, but that Germany was ready to make compensation for the wrong committed. What was the British attitude on the same question? The day before my conversation with the British Ambassador, Sir Edward Grey had delivered his well-known speech in Parliament, wherein, while he did not state expressly that England would take part in the war, he left the matter in little doubt. One needs only to read this speech through carefully to learn the reason of England’s intervention in the war. Amid all his beautiful phrases about England’s honour and England’s obligations we find it over and over again expressed that England’s interests – its own interests – called for participation in war, for it was not in England’s interests that a victorious, and therefore stronger, Germany should emerge from the war.

REICHSKANZLER THEOBALDVON BETHMANN-HOLLWEG,4 AUGUST 1914

When the Germans crossed the Belgian border, the British guarantee to support the independence of the 100-year-old state was tested. And though the Entente Cordiale between France and Britain was no formal military alliance, there was equally no chance that Britain would stay out of the war. The growing challenge to Britain’s maritime hegemony – and the possibility of the fall of the Channel ports – were significant and tangible. Britain was to support the French, and come to the aid of ‘gallant little’ Belgium. From August 1914, the miniscule British army faced its toughest enemy in the Germans, who outnumbered them ten times, and who were an unfamiliar foe.

Almost as the first six British divisions crossed the English Channel, the propaganda battle began. Attributed to the German Kaiser was an infamous, contemptuous view of the British, a matter widely reported in the British press in August 1914:

THE KAISER’S SPITE

At a conference, held last Wednesday week, at the Imperial headquarters at Aix-la-Chapelle, of his general officers commanding divisions and brigades of the German Northern Army, it is said that the Kaiser issued this grim order:–

It is my Royal and Imperial command that you concentrate your energies, for the immediate present, upon one single purpose, and that is, that you address all your skill and all the valour of my soldiers to exterminate, first, the treacherous English; walk over General French’s contemptible little army.

That explains why the flower of the German Army was flung against the British troops.

YORKSHIRE EVENING POST, 29 AUGUST 1914

Contemptible? The term was quickly adopted as a badge of honour by the British soldiery, fuelled on by the press reports. The idea that the British would be swept aside was fiercely opposed by the men themselves:

He [the Kaiser] is trying … to break through Britain’s contemptible little army but he shall get a prod and a very good one at that.

CPL J. BREMNER, ROYAL GARRISON ARTILLERY, 27 JANUARY 1915

But an absence of documents and supporting statements undermine the existence of this order. The Army Historical Branch could track nothing down, and neither could Major General Sir Frederick Maurice; the MP Arthur Ponsonby dismissed it as a clever British propaganda ploy. In fact, the German High Command had greater respect for the British army than has so far been considered. The Germans never underestimated their enemies:

The BEF is a first-class opponent. The officer corps is recruited from the best classes. It is united and morale is excellent.

GERMAN ARMY MEMORANDUM, 1914

[English officers] studied on the battlefields of Manchuria and they can be found on the manoeuvre grounds of all major military powers, always ready to observe, compare and to learn. What they have learned they take home to England where it is evaluated by the General Staff which in its current form has only recently been set up by Haldane, before making the information accessible to the army. Large scale manoeuvres are today just as common in England as they are on the continent … countless battlefields all over the world and a glorious history stand proof to the fact that he [the English soldier] was always ready to fight and to die bravely for the honor of his arms. The English Army, set into a natural, warlike state by an outstanding reformer and trained by its appointed leaders commands the respect even of continental armies.

GERMAN GENERAL STAFF, 1909

Despite this, the propagandists – reacting to the actions of the German army in Belgium and France in 1914 – ensured that the enmity of the two nations would deepen from very early on. Pre-war, intellectuals had a respect for German learning, but even this would be tested and challenged in the wake of the enhanced tale-telling of atrocity stories, in newspapers, on posters, in everyday life:

‘We have not beaten the enemy, but we have set a new world record – in running.’ British soldier pictured in German propaganda – always thin, awkward and oddly dressed.

Conversely, the Germans were usually portrayed as overweight buffoons in British propaganda.

‘ONCE A GERMAN, ALWAYS A GERMAN’

REMEMBER!

This Man, who has shelled Churches, Hospitals, and Open Boats; this Robber, Ravisher and Murderer, And This Man, who after the War, will want to sell you his German Goods, ARE ONE AND THE SAME PERSON! Men and Women of Britain! Have nothing to do with Germans Until the Crimes Committed by Them against Humanity have been expiated!

POSTERBY DAVID WILSON, 1918

For the Germans, the perception of British perfidy in siding with the French, meant that the ‘Hymn of Hate’ targeted its greatest enemy:

Hymn of Hate

French and Russian, they matter not,

A blow for a blow and a shot for a shot!

We love them not, we hate them not,

We hold the Weichsel and Vosges gate.

We have but one and only hate,

We love as one, we hate as one,

We have one foe and one alone.

He is known to you all, he is known to you all,

He crouches behind the dark grey flood,

Full of envy, of rage, of craft, of gall,

Cut off by waves that are thicker than blood.

Come, let us stand at the Judgment Place,

An oath to swear to, face to face,

An oath of bronze no wind can shake,

An oath for our sons and their sons to take.

Come, hear the word, repeat the word,

Throughout the Fatherland make it heard.

We will never forego our hate,

We have all but a single hate,

We love as one, we hate as one,

We have one foe and one alone –

ENGLAND!

ERNST LISSAUER, 1914

But what was the actual relationship between the Germans and the British troops? Though shaped by the virulent propaganda at home, this relationship was also born from the actions of the soldiers at the front.

‘The helpful English (when spotting the Pickelhauben) – running away in fright.’

Surrender was a constant theme in British propaganda representations of the Germans.

It is the Christmas Truce of 1914 that has captured the imagination of many, for it was across the frozen fields of France and Flanders that the soldiers of both nations met each other on equal terms without enmity – albeit briefly. The motives for the truce have been much discussed, and whether it was through curiosity, cynical opportunity to examine the trenches of the enemy, or simply the chance to give the war a rest, Briton and German met in no-man’s-land without weapons. There are many accounts. At Frelinghien and Houplines, British soldiers of the 6th Division met their German counterparts face-to-face:

On Christmas morning some of us went out in front of the German trenches and shook hands with them, and they gave us cigars, cigarettes, and money as souvenirs. We helped them bury their dead, who had been lying in the fields for two months. It was a comical sight to see English and German soldiers, as well as officers, shaking hands and chatting together. When we had buried their dead one of the Germans danced and another played a mouth organ. We asked them to play us at football in the afternoon, but they had no time. They seemed a decent crowd to speak to, and I got into conversation with one who had worked at Selfridge’s in London, and he said he was sorry to have to fight against us. Well I don’t expect we shall shake hands with the enemy again for a long time to come.

RFN ERNEST W. MUNDAY, 3RD RIFLE BRIGADE,26 DECEMBER 1914

At Aubers, a German infantryman recorded his experiences of this spontaneous event:

25 December 1914. Today the troops on both sides seem to be in tacit consent not to shoot at each other, not a single shot is fired. In front of another company Germans and Englishmen met between the trenches and agreed upon a ceasefire. If we were to open fire again we were asked to fire five shots into the air; a warning signal which the English would then answer in the same manner. At another place Schnaps and cigarettes were exchanged. Later our Oberleutnant ordered the company to assemble and gave us a severe reprimand. Each and every one of us would get court martialled and every Englishman that came over to our trenches was to be taken prisoner. Later we received an incredible amount of presents and merrily celebrated Christmas. Bolsinger is dead and tomorrow we may well be too so let us be merry as long as it is possible. Merry Christmas and a happy new year!

Retouched image from the Illustrated War News (1915) depicting the incredible events of Christmas 1914.

26/27 December 1914. We and the English soldiers have agreed upon a ceasefire. We met between the trenches and exchanged cigarettes for tea. Spoke to three English soldiers, one of them a corporal. I gave him an open letter for Elisabeth in England and dictated him her address, he promised to deliver it. Actually they were not Englishmen but Scots. Scottish Guards; strong men all of them, even though they appeared to be even more dirty than we were. Their uniform is cut similar to my hiking suit and has about the same colour. They also wear puttees and laced boots.

LTN. HEINRICH EBERHARD, INFANTERIE-REGIMENT NR. 158

The Truce would soon be left behind as the war deepened, and there would be many fierce encounters to come. The relationships between the armies cannot simply be defined by its incredible events – but it does underline the interest with which both sides viewed each other.

This book represents the first time that two authors – one British, one German – have attempted to examine the lives of their forebears in a single volume, comparing them. There are distinct differences. The standard of German education meant that many low-rank letter writers were articulate, while the cards and notes written by British other ranks were often stilted and formulaic. And with German letters and cards written in their billions, the system of local and base censorship soon went into abeyance, with German soldiers describing in some detail the nature of their surroundings, the state of the trenches, the progress of battle. British letters, strongly controlled and actively censored, were that much more cautious. Despite these constraints, what emerges is the depth of meaning that is carried by the details of their writing and the words used by the combatants. Was the relationship between enemies just what was represented by the propagandists of both sides? Through their writing we hope to find out. In this book, we examine the time of mobilisation, life at the front, the sustaining of morale, the act of battle and of death, and the end of the war.

To us, the very act of writing this book is a simple act of remembrance of those men, of Fritz and Tommy, who fought and returned, to the Heimat and Blighty,and to the millions who were left behind in the fields of Westfront/the Western Front. We dedicate it to their memory.

1

The Armies/Die Armeen

Why did I volunteer? Certainly not because of any kind of enthusiasm for war or because I think it is a major thing to shoot people or to get a war decoration of some kind. The opposite is the case, war is a wicked thing and I also think that by using more skilful diplomacy it should have been possible to avoid it.

But now that there is a war, it is quite natural that I unite my own personal destiny with that of the German people. And even though I am sure that I would have been able to achieve better things for Volk and Vaterland in peacetime than in war it feels wrong to undertake such calculating observations. It is like comparing one’s own value with that of a drowning man to find out if he is worth saving ….

KRIEGSFREILWILLIGER FRANZ BLUMENFELD, RESERVE-FELDARTILLERIE-REGIMENT NR. 29, 24 SEPTEMBER 1914

Then the first war broke out and the early news of the invaders terrorising the women made me feel that must not happen here so I decided to enlist.

PTE HUMPHREY MASON, 6TH OXFORDSHIREAND BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY

The armies of Britain and Germany were distinctly different. In organisation, national characteristics, recruitment and logistics, the two armies moulded and shaped their soldiers. It is necessary to examine their differences in some depth.

The Germany of 1914–18 was forged from the wars of unification, the Reichseinigungskriege, fought between 1864 and 1871, which led to the creation of the Deutsches Reich. In particular, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 saw the total defeat of the French army, and the reputation of the armies of the newly unified German state, the Deutsches Heer, was second to none. The German military system was superbly efficient and was locked into everyday life. It committed almost all males to a period of service that would carry them through from young man to older reservist. And every man was efficiently trained according to a system that prepared the German army for its ultimate challenge when world war erupted in August 1914.

For Britain, a maritime nation with a significant array of overseas possessions, the events on the continent were seemingly remote, and there was a reliance on the navy to represent its greatest force of arms. While the German forces were engaged in Europe, the purpose of the British army was very different; it was there simply to provide an Imperial police force, used to maintain borders and put down insurrections or unrest. It was used in fighting ‘brush-fire’ wars against native rebellions.

Following the entente cordiale of 1904, the possibility that Britain might have to field an army in Europe meant the creation of an expeditionary force of six divisions of all arms and a single cavalry division. Each division, based across Britain until needed, had a war establishment of some 18,000 men, 12,000 of which were infantry, and the remainder artillery – together with, in 1914, twenty-four machine guns and seventy-six artillery pieces. Each infantry division was composed of three brigades (c. 4,000 men), each brigade of four battalions (c.1,000 men each). Battalions were derived from each regiment, and it was highly unusual for battalions from the same regiment to be brigaded together. The regular infantry divisions that were embodied in 1914 and destined to serve overseas were supplemented by others that were assembled to carry forward the British responsibilities that deepened from 1914. First, there was the assembly of regular battalions recalled or returned from overseas service as new regular divisions. Second, the ‘first line’ Territorial battalions were formed into divisions of men who had volunteered to serve overseas; second line battalions, formed to serve at home, would wait their turn. Finally, there were ‘New Army’ divisions, composed of the volunteers for Kitchener’s Army from 1914. They would amass some seventy-four infantry divisions by the war’s end. Added to this were three regular cavalry divisions and four mounted yeomanry. Each was supported by regular, Territorial and ‘New Army’ artillery, engineer and support troops.

On mobilisation in 1914, and conforming to French practice, it was decided to group British divisions into corps each comprising two divisions, such that the British Expeditionary Force, when it landed in France, consisted of three army corps. In all these units, additional manpower was available in attached army, corps, division and brigade troops, and headquarters staff. As the war progressed, so the drain of manpower increased; by late 1917 the number of brigades per division was reduced by one. In 1914, the cavalry division was organised differently, with four brigades of three regiments each (together with attached troops), having a strength of 9,000 men, 10,000 horses, twenty-four machine guns and twenty field guns. It was with this structure that the British army went to war, and it was this structure that provided the expeditionary force that landed in France in August 1914.

In comparison with the British unified system, the Deutsches Heer was a federal force that comprised armies of the four kingdoms of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony and Württemberg, together with representatives across the twenty-one minor states of the Deutsches Reich. Of these nations, only Bavaria employed a separate numbering system, the other states following that of the Prussians. Taken together, however, in July 1914 these contingents meant that Heer could muster a strength of 840,000 men: the second largest army on the continent, second only to the Russians. And within a week of war being declared, with the reserves called up, that figure was pushed up to nearly 4 million men, and reached a peak of around 7 million in 1917.

It was the Kaiser who held overall command of the Heer – including the Bavarian contingent – and exercised control through the Ministry of War and the Großer Generalstab (Great General Staff). The basic peacetime organisational structure of the Heer was a hierarchal system, with Armee-Inspektionen (army inspectorate), Armee-Korps, Divisionen, and Regimenter. The Bavarian Army served on the Western Front as an integral component of the German army, while the armies of Saxony and Württemberg formed self-contained army corps. The minor German states, kingdoms and duchies also provided separate units of mostly regimental size that served as part of the Prussian contingent.

Armee-Korps were virtually independent formations receiving orders directly from the Kaiser. Composed of two infantry divisions, each division was formed from two brigades with two infantry regiments each and two cavalry brigades with two cavalry regiments each together with a Fußartillerie (‘foot artillery’ – mobile field artillery) regiment. In addition, each Korps had single Jäger (elite light infantry), pioneer, and train battalions, and other support troops. The Infanterie-Division was the basic tactical unit.In summer 1914, in addition to the units of the Garde-Korps, there were forty-two regular divisions in the Prussian Army (including four Saxon and two Württemberg divisions), and six divisions in the Bavarian contingent. As the war progressed, reserve divisions were formed as the need for more men increased.

The basic combat unit was the regiment. Early war German infantry regiments typically had a strength of 3,300 officers, NCOs and men, and one machine-gun company with six heavy MG08 machine guns. By summer 1918, the serious shortage of personnel forced a reduction to about 700 men while many battalions with fewer than 650 men were reduced to three rifle-companies. By 1916 so-called Sturmbataillone (assault battalions) were formed on army level. These units were not only elite shock troops at the front, but also acted as schools for regular infantry units.

German regiments were raised and maintained at a local level. Large cities and towns could muster an entire regiment, while smaller rural areas would be responsible for raising a company or battalion for the local regiment, which meant that the whole system became ingrained deeply into the social structure of the country. During peacetime, military service was very much like a social club. One could serve the entire twenty-two years required by the army alongside one’s family, friends and neighbours; this forged very strong bonds of loyalty and friendship to a regiment, a factor that was useful for morale in battle:

My address is 11/55 – 11th company, Regiment Nr. 55 in Detmold. Tomorrow we will hopefully receive our uniforms and in the meantime we are sitting around in the barracks. Here and among the reservists I have met many old friends and acquaintances, so all is well. A 1000 kisses, your son Paul

MUSK. PAUL VIETMEYER, INFANTERIE-REGIMENT NR. 55

The downside, always the case with local regiments and equivalent to the experience of the British, was that during the war small towns might find many of their young men killed, wounded or missing in a single day.

The 22 October 1914, a day that no member of the regiment will ever forget. A foggy, chilly and damp morning; a rosy-fingered dawn on the horizon. A day that had brought nameless grief and sorrow to the relatives and families at home. Countless people were talking to each other on the streets of Hannover and Hildesheim, asking for news of their 215th regiment. For hours mothers and fathers were waiting on the station platforms where the trains carrying the wounded were coming in, until the news arrived: ‘Fallen on the field of honour’ or ‘missing’. ‘Missing’ – what a terrible word, which turned the feeling of trembling suspense into a horrible suffering. Countless requests at the central registration office remained without answer. The regiment had hundreds of soldiers missing. Some clarity was gained, but the ultimate fate of 50 comrades will forever stay a mystery. They rest as unknown soldiers in the cool, foreign soil.

HISTORYOF RESERVE-INFANTERIE-REGIMENT NR. 215

German recruits muster in 1915.

If, in 1914, the British army could trace its origins back 300 years, this could be matched equally by the Germans. The oldest regular German regiments had histories that stretched back to the early seventeenth century. In at least three major conflicts – the Seven Years War, the American War of Independence and, most notably, the Napoleonic Wars – German states and their armies stood as allies alongside the British, earning battle honours that would be recognisable by regiments on both sides of the North Sea. But not all regiments in the Deutsches Heer could claim this longevity; there were the thirty-three so-called ‘Young Regiments’ – raised in 1896 – that had no antecedents, and consequently possessed no battle honours. They would have their chance to earn them in the coming conflict – as could the Reserve Regiments formed on and shortly after mobilisation in 1914.

Following the reforms of the British army in 1908, in 1914 there were sixty-one British regular infantry regiments, ranked in an order of precedence set by tradition which placed the five regiments of Foot Guards above the county regiments of Infantry of the Line, the rifles sitting towards the end of this list. Each infantry regiment was named, usually after the county of association, having left their numbers behind following reform. Each one had two regular battalions allied with a county or region, and each was given a home depot. The third or Special Reserve Battalion was designed to gather recruits for the regular battalions, while the fourth, fifth and often sixth battalions belonged to the Territorial Force – though Irish regiments were never to have Territorial battalions. There were also five all-Territorial regiments.

The naming and numbering of German regiments was complex. In 1860, Prussia started numbering its regiments in a system that did not follow any particular chronology, and after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 the Prussian-annexed states integrated their armies into this system. Württemberg and Saxon units were numbered according to the Prussian system, while Bavaria maintained its own (thus, the 2. WürttembergischesInfanterie-Regiment was Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 120 under the Prussian system). But initial numbers were just part of the story. In addition to them, all regular regiments possessed a name, a state or provincial number, and usually an honour title too.

In common with the British army, many regiments carried the title ‘Grenadier’ or ‘Fusilier’ – throwbacks to an earlier age – and many proudly displayed regimental traditions on their helmet plates, or on their uniform. One such title is the award of the battle honour ‘Gibraltar’ to both British and German regiments, a function of the siege that took place in 1779–83, during the American War of Independence. With German-born King George III of Great Britain and Ireland also the Duke of Hanover, three Hanoverian infantry regiments were sent with five British units to defend Gibraltar in 1775. For their endurance and loyalty, during three years of siege they were granted the battle honour ‘Gibraltar’. The descendents of all these regiments – the British Suffolk, Dorsetshire, Essex and Northamptonshire regiments, and the Highland Light Infantry, and the German Füsilier Regiment General Feldmarschall Prinz Albrecht von Preußen (Hannoversches) Nr. 73, Infanterie-Regiment von Voigts-Rhetz (3. Hannoversches) Nr.79, and Hannoversches Jäger-Bataillon Nr. 10 – shared the Gibraltar title. It must have been an unusual sight for British soldiers mindful of regimental history to meet Germans proudly wearing their cuff title. It was certainly an honour that celebrated stormtrooper Ernst Jünger was proud to wear:

Whenever we appeared on some sector of the front, we heard the shouts of ‘Les Gibraltars, les lions de Perthes’.

LTN. ERNST JÜNGER, FÜSILIER-REGIMENT NR. 73

Mobilisation

At 7:30am all reservists in our street and from the neighbourhood assembled and together we marched out to report at the barracks. On the way more men and young volunteers attached themselves to our column. Countless people lined the roads, they cheered and sang ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’ and ‘Deutschland über alles’. Young boys carried their fathers’ luggage. What a great and moving experience it was ….

SCHÜTZE W. HIMMES, RESERVE-INFANTERIE-REGIMENT NR. 91, 2 AUGUST 1914

For the Germans, the First World War was fought mainly by armies of conscripted citizen-soldiers, as had been done since the early nineteenth century. Under the Imperial Constitution of 16 April 1871, every able-bodied German male between the ages of 17 and 45 was liable for compulsory military service. Exemptions from service were allowed on the grounds of family distress, as well as the continuation of education.

German military service was divided into four phases. After active service, the conscript passed in turn to the reserve, the Landwehr, and the Ersatz-Reserve (supplementary reserve), amounting to twenty-two years of service. Active service in the Heer meant two years in the infantry or a non-mounted artillery unit. Three years were demanded by cavalry and mounted artillery.

Personnel discharged from active service passed into the Reserve,and all soldiers were expected to have served a combined total of seven years. Reservists had to take part in regular training courses and army manoeuvres spanning up to eight weeks a year. A transfer to the Landwehr followed. Service in the Landwehr typically lasted for another five years (for infantry, for example), but was reduced to three years where the original active service had also demanded three years. Landwehrmänner were required to participate in two manoeuvres each year amounting to four weeks in a year. Personnel surplus to requirements (Restanten) were transferred into the Ersatz-Reserve, which acted as a ready manpower pool for active units. Finally there was the Landsturm, comprising men aged between 17 and 45 who did not qualify for one of these service groups.

Inspection at 3:45pm. It has been too long since I have been a soldier. I do not think that I will be able to survive the first enemy attack and I can only hope to get used to all this again.

DIARYOFANUNKNOWN LANDSTURMSOLDIER

All young men in a calendar year were grouped together and referred to as a Jahrgang (year group), a group that would serve together in the future. Though the conscript system was highly organised, there was still a chance for a young Landsturm soldier to choose to volunteer before his year group was due to be called for active service. If he was physically and mentally able, the volunteer might qualify for a fashionable regiment or could follow a family tradition of serving in a noted unit.

The final decision on which arm of service a conscript would be serving in was made by the Ober-Ersatzkommissionen,based on his physical and mental abilities. While this system worked well in peacetime, the sheer volume of volunteers in the early weeks of August 1914 rendered it virtually inoperative. To cope with the massive numbers of Kriegsfreiwillige, individual units often distributed them randomly, but during the course of the war and after the first rush of euphoria had died down, the system was largely back in place again. Another class of volunteer was the Einjährig Freiwilliger – young men of ‘suitable social class’ and education who could enlist as a ‘one-year volunteer’ in order to shorten their active service period:

Highly honoured Professors!

As our beloved Fatherland is in grave danger I have decided to give my strength and blood to Kaiser and Reich and to take part in the fighting that needs to be done. Now, since 16 August, I am a soldier and I take the liberty to send my Professors the most heartfelt wishes! I have joined Infanterie-Regiment 23 as a One Year Volunteer and I am now part of 3. Ersatz-Kompanie.

Your always grateful student

KRIEGSFREIWILLIGER OTTO SCHLECHTER, RESERVE-INFANTERIE-REGIMENT NR. 23, 31 AUGUST 1914

To be allowed to join in this way, a recruit had to pass a special one-year certificate in his Gymnasium (grammar school). This would earn him the right to choose the unit he wished to serve with – though he was still expected to equip, feed and house himself from his own pocket. In an infantry unit this amounted to between 1,750 and 2,200 marks – a substantial sum of money. Joining as a volunteer was a considerable decision for a young man to take:

My parents!

I decided to write to you, not because I am afraid of a debate but because I want to give you time to muse about your decision. This letter is not the result of a spontaneous idea, I have given everything a long thought, weighed the pros and cons and came to the same result, over and over again. One thing I have to emphasise: whatever your decision is, I will accept it without complaint as my experiences taught me that parents are always right.

But now let me tell you the reason I am writing this letter. I want to move into the field! All of my colleagues, from school and from work dropped everything to follow the call of the Kaiser. Do you want your son to be the exception? Their parents and siblings cry, but they are proud of their sons and brothers. Men between the age of 25 and 40 years have already taken up arms, even though they had to leave their women and children and even though there is the uncertainty that their loved ones might now succumb to hunger and need. And I, having no such obligations, am supposed to continue standing behind a shop counter to sell rolls of yarn to our customers and to answer countless questions about why I have not joined up yet?

I have the strength to defend my family and fatherland, but I prefer to work in this shop as this is a lot safer! Dear parents, would you want me to say that? Certainly not, because you would be ashamed of me.

A Leutnant who regularly visits our shop, but so far has not been granted the honour of serving at the front told me that at the moment there are so many volunteers that uniform stocks have been temporarily exhausted. Now they are offering that every volunteer will be trained to become an Unteroffizier. This training will last for three months. Conditions: 1) A One-Year Certificate; 2) 300 Marks to pay for expenses; 3) I have to buy my own uniform, underwear, socks etc. The training will begin on 11 August and minors need the written and signed consent of their parents to join!

If I supply all this I will be an NCO in three months. If not, I might get called up in a few weeks anyway and then I will only be an enlisted man – what do you prefer? Please remind yourselves that uncle Karl sent both his sons to serve under the colours! I will visit you at 10 o’clock to receive your answer.

KRIEGSFREIWILLIGER HANS BUCKY, INFANTERIE-REGIMENTNR. 153

At seven in the morning the artillery barracks here in Oldenburg started recruiting volunteers. There must have been around 1,500 young men on the square, but they only accepted 440 who were then divided into four depots with 110 men each. I am now in the 3rd depot and already met some old friends here.

GEFREITER OTTO BORGRÄFE, FELDART.-REGIMENT NR. 62, 15 AUGUST 1914

In August 1914, the Reserves were called up and the Deutsches Heer required only twelve days to expand from about 840,000 to a total of 3.5 million soldiers. Upon mobilisation, the Reserve and Landwehr regiments were activated:

This morning we were sworn in. At 8:10 am we assembled and marched to the church. Pastor Wilksen delivered a sermon in which he highlighted the righteousness of the German cause. At 10:20 we assembled on the barrack’s square at the Zeughausstrasse to take our oaths. On the square there were six artillery pieces on which we had to place our left hands, the right hand raised to deliver the oath. The recruits were grouped by nationality and confession and everyone delivered the oath as it fitted his religion and on his local ruler. I was sworn in on His Royal Highness the Grand Duke Friedrich August of Oldenburg. The whole ceremony lasted for about an hour.

GEFR. OTTO BORGRÄFE, ERSATZABTEILUNG FELDARTILLERIE-REGIMENT NR. 62, 23 AUGUST 1914

Personnel from Reserve regiments were used to bring the regular active regiments to Kriegsstärke (war strength), while Landwehr soldiers were moved up to bring Reserve units up to strength. The Landwehr regiments were the last to depart the garrisons, and were often not fully manned:

After I left, Gustav accompanied me to the station and at 10:27am, I and the other Reservists, among them Stuck, Schwarze and Weingarten, took the train to Detmold. All stations are bustling with activity and trains packed with soldiers roll by, most of them go towards Cologne. Everyone is singing and there is a cheerful atmosphere. We arrived at Detmold at 12:00 and reported at the barracks. After the paperwork had been done we marched into the ‘Preussischer Hof’ where we were accoutered in the dining hall. I had difficulty to find a fitting tunic and trousers and as I did not find a pair of riding breeches I had to content myself with a pair of cloth trousers. I did not even find a cap and the helmet I got is too large. I and about 20 other NCOs are now attached to the reserve baggage train.

UNTEROFFIZIERDER RESERVE HERIBERT BORNEMANN, TRAIN-BATAILLON 7, 4 AUGUST 1914

As units departed, they were replaced by corresponding cadre units, the so-called Ersatzbataillone (replacement battalions), three of which were put in place for each of the unit’s active, Reserve and Landwehr components. Through these units, the Feldtruppenteil (field unit) would receive its flow of trained replacements:

I was recovering from my wound and by the beginning of January I had recovered so far that I was to do garrison duty again. There is lots of work in the Ersatzbataillon. On 20 January a company of 100 recruits arrived. They are supposed to receive a further 6–8 weeks of training, so they are not going to be sent into the field soon. They are a keen lot and full of ardour, but a good number of them will fall down on the job as the physical strain seems to be too much for them. I suppose 10–15 per cent are unfit for service.

UFF3. WALTHER PAUER, KÖNIGLICH BAYERISCHES 11.

INFANTERIE-REGIMENT, 25 FEBRUARY 1915

While the German system worked well in times of peace, the horrendous casualties suffered in combat during the war greatly reduced its effectiveness. The first result of that was a continual lowering of the induction age as the fighting at the front wore down the available manpower reserve. By 1918, the members of Jahrgang 1920 were being called to service, fully two years ahead of time. These were the young soldiers so often pictured as prisoners of war by the Allies, eager to portray the defeat of Germany.

While Germany espoused its system of military compulsion, Britain stuck rigidly to the principle of a volunteer army. Haldane’s reforms ensured that, for infantry regiments, there would be at least two regular battalions for the county regiments, recruited locally. There was also a special reserve battalion which remained at the county depot and supplied drafts of reservists, and at least a further two Territorial battalions. It was this system that ensured there was an efficient means of expanding the army, using the local Territorial Associations that existed to serve to support their Territorial battalions, now affiliated to the regulars. The idea was to provide an expanding reserve:

It was Mr Haldane’s intention to make the County associations the medium for indefinite expansion of the forces in case of need … the County Associations justified Mr Haldane’s faith in them, and their zeal and ability were of the utmost value to the War Office and the country.

BRIG.-GEN. J. EDMONDS

In the early stages of the declaration of war, the British system snapped into place. Regular troops on leave were recalled, while those men who had recently left the army, and who were liable for a normal five-year service (Category B men) in the reserves were called back to the colours, and formed a significant component of the regular army battalions. Reservists in Category A could be called back for any perceived need; Category B men required a general mobilisation. The words of reservists have largely been overlooked in the mass of volunteers and conscripts:

Recruits of Feld-Artillerie Nr. 56 in 1914.

Being a Reservist, I was naturally called to the colours on the outbreak of war between England and Germany on August 4th, 1914, so I downed tools; and, although a married man with two children, I was only too pleased to be able to leave a more or less monotonous existence for something more exciting and adventurous.

PTE FREDERICK BOLWELL, LOYAL NORTH LANCASHIRE REGIMENT, 1914

Reservists reporting to the regimental depot had to start again from scratch, including seeking out their uniforms from the store:

On August 5th 1914, I reported to my regimental depot being an Army reservist. What a meeting of old friends! All were eager to take part in the great scrap which every pre-war soldier had expected. In the mobilisation stores, every reservist’s arms and clothing were ticketed, and these were soon issued with webbing equipment.

PTE R.G. HILL, 1ST BATTALION ROYAL WARWICKSHIRE REGIMENT, 6 AUGUST 1914

The Territorials, known sneeringly as ‘Saturday night soldiers’, had signed on for a typical commitment of four years, and were required to attend regular parades at the local drill hall and an annual summer field camp. ‘Time expired’ men could sign on again for another four years. It was expected that the Territorial Force would form the ‘Second Line’ – Britain’s home defence with no overseas obligation, but they could be expanded in times of need. But it was obvious that even with the actions of the County Associations, it would be difficult to get sufficient men to supply a major commitment overseas:

The Battalion has volunteered for foreign service, and will go as a battalion. Eighty per cent volunteered, and of the remaining 20 per cent some have applied for commissions. We have started recruiting again to fill up from 800 to 1,000, so as to go at full strength.

PTE D.H. BELL, LONDON RIFLE BRIGADE, 28 AUGUST 1914

Things changed dramatically when Field Marshal Lord Kitchener was brought in to lead the War Office. Despite his lack of political acumen, with his breadth of experience in the Victorian ‘small wars’, he was an obvious choice as a war leader for the government. And he soon shocked the cabinet with his assessment of the probable length of the war. Kitchener was summoned to the War Office to take on the direction of the war and to take a seat in the cabinet. Impatient with the current recruiting system, and in the knowledge that maintaining an adequate flow of soldiers to the front would be of great importance, the Secretary of State for War made a direct appeal to the public for more men. The first appeal was for 100,000 men, an appeal that would be driven by his own image pasted up on bill-boards and recruiting offices:

British soldiers in camp; Grenadier guardsmen relax in their hut.

The task the Government set itself was a formidable, nay, a staggering one. It was in the first place to take 500,000 raw men from the streets, from the clubs, from the fields, from the villages, towns and cities of Great Britain, and not only to train them in the art of war in the shortest space of time that it is possible to train soldiers, but also to prepare the equipment, the arms, and the munitions and stores of war.

EDGAR WALLACE, 1916