23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

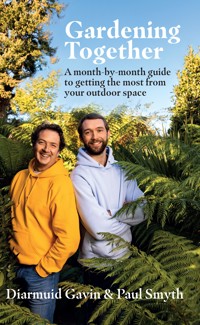

Create and maintain a stunning and fragrant garden with Ireland's favourite garden designer Diarmuid Gavin and plantsman extraordinaire Paul Smyth as your guides. Find out when to prune your hydrangea, which soil suits potatoes, how to keep your lawn green and moss-free, and learn how to plan ahead with this beautiful and practical gardening book. Packed with gorgeous photos, simple tips and tricks, and inspirational advice on plants, this book will show you month by month how to achieve striking colour schemes, enchanting scents and fabulous foliage, as well as how to plan and create a garden design to suit your lifestyle. Inspired by Diarmuid and Paul's TV show and online conversations, Gardening Together follows the pair in a garden year from January to December, with a monthly look at what you need to do to enjoy and appreciate your outside space like never before.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

To Justine

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

Frequently Asked Questions

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill Books

Introduction

Hello! Welcome to our book, Gardening Together.

First, a brief introduction. We are Diarmuid Gavin, garden designer, TV presenter and podcaster, and Paul Smyth, plantsman, propagator and … podcaster!

We’re both from Ireland and we’ve worked on this island and in many other places around the globe. We love plants, we’re interested in how they grow, and we love using collections of them to create gardens. A few years ago we started working together, planting gardens and broadcasting over Instagram. And those connections have led to our podcast, Dirt, and now this, a book based on many garden conversations we’ve enjoyed through the changing seasons.

Gardening is changing. More people than ever before are interested in gardening, so follow us on our garden-year journey from January to December. We take a month-by-month look at gardens and aim to provide some simple tips and tricks you can use to create your dream garden. Whether you’re brand new to gardening or a dab hand at the potting bench, we hope to inspire, delight and inform you so that you will get the most out of your space all year round.

Diarmuid’s story

We made the big move from London to Wicklow 13 years ago. Eppie, my daughter, was just two, and the house we chose was a new-build nestled in an idyllic location at the foot of the Sugarloaf but still just 35 minutes from the airport.

Our garden consisted of a third of an acre of builder-laid sloped lawn looking out to a field beyond. I’d find out soon enough that the ground was a challenge to dig, but for the first few years I did very little. Designing my own garden proved to be an unexpected challenge. I knew what I wanted – to tame the slope by introducing terraces, to grow a lush green Wicklow jungle using architectural plants such as the tree fern (Dicksonia antarctica), bananas, cannas and bamboo. I also planned to grow some fruit trees and have an area for vegetables, and I wanted to build a pond. I wanted to live up to the principles of design I’d always believed in – which is to blur the lines between home and garden.

The house was a big bland box, with small windows to the rear, from which there was a great view of trees, fields and mountains. I needed to find a way of bursting through the pebbledash and opening it to the garden. The dream was to be able to wander from each room upstairs onto a wide balcony or veranda under the cover of an overhanging roof and use the upstairs space as an outdoor room.

The dream had to wait while reality kicked in. There were other priorities – swings and a trampoline, and open space for exuberant puppies. And I’d emptied the bank buying the house, so the garden would have to evolve slowly.

The realities of the plot were also sinking in. Building the house had led to severe soil compaction. A meagre amount of topsoil had been spread over this compacted soil, and once I began to dig I unearthed a small quarry’s worth of shale and boulders. My dream garden would take some time to realise, and a lot of backbreaking work would be required. Time turned out to be a blessing, though, as living with the space for a couple of years led to my imagination kicking in. And time allowed me relax into the search for the structures I needed to start work.

Eventually I found what I was looking for: nine hundred-year-old cast-iron columns lying in a city architectural salvage yard. They were marked as having been made in Bristol in 1895 and were formerly used to support part of a city-centre hospital. They could now support the framework for a second-level terrace and roof, meaning that I could have a wide second-level veranda. This notion had been inspired by my travels, especially trips to New Zealand, South Africa, Florida’s Key West and Venice Beach in California. Outdoor living has been key to architectural development in these countries and I believe it should also be in ours.

My breakthrough moment came in Charleston, South Carolina. I was filming at a colonial ranch where the movie The Notebook had been made, and in the city I hired a bicycle and came across the area’s iconic ‘single’ houses – long, narrow homes with piazzas that stretch down the entire side. This distinctive house style was shaped by the city’s hot and humid summers and the homes are oriented specifically to take advantage of cooling breezes.

Wicklow offered a more pleasant climate, and there was less of a requirement for cooling air, but the protection of a protruding roof would make a useful umbrella from our regular rain, which arrives as gentle droplets or torrential downpours. A covered veranda would also allow an unusual view over the garden and let me indulge in my love for tree ferns – as viewed from above!

There were missteps. My first deadline was to have the veranda up and the garden tamed in time for Eppie’s holy communion party. I was garden gallivanting abroad and the contractor chosen to install lawns, terraces and ponds proved to be a disaster. While the garden looked good, underneath the newly laid turf the soil had once again been heavily compacted with machinery; sand rather than topsoil had been used as a bed for the lawns; and the ponds leaked! I would spend years undoing the damage.

More time passed and eventually, just five years ago, I began to get serious about the plot and started planting in earnest. Saturdays were spent in garden centres and nurseries. My penchant was always for trees first – we’ve squeezed in about 60 – and then broad-leaved architectural species: the lusted-after giant ferns, cannas, Musa, cordylines and ornamental gingers.

Suddenly, after eight ‘nothing’ years, it seemed we had the beginnings of a jungle. Renowned gardener Helen Dillon came for Sunday lunch and brought a beautiful magnolia, ‘Leonard Messel’, which has pride of place in the collection; and I found a gorgeous tetrapanax at Architectural Plants. Other leftover plants from projects were fitted in, like the conical bay trees that had once revolved at the Chelsea Flower Show and that now form evergreen pillars in this Wicklow plot. There’s even a sequoia and a monkey puzzle, so in a few years decisions will have to be made about what stays. That’s the fun of planting a garden.

The real revelation was Geranium palmatum happily self-seeding under the tree ferns and producing a haze of pink froth from late April through to mid-July. We had to pinch ourselves. We were at last developing a garden we loved. There were garden arguments along the way – I wanted less lawn and more plants, so the grass was gradually consumed. And I’d no sooner start on a project than I’d dream up another. These projects were becoming like painting the Forth Bridge; it’s such an involved and time-consuming process of improvement that it never truly ends. And this was at odds with my lifestyle. I worked abroad so I’d arrive home around 11.30 on a Friday night and, first thing on Saturday morning, wander into the garden, bleary-eyed and barefoot, dogs yapping at my ankles. I’d look for what had happened while I was away – what was growing, budding, flowering? What wasn’t? What needed doing? My plot eyed me back suspiciously; it was fine, thank you … no need of your help … we’re all doing okay without you. Then, after a mug of strong coffee, and armed with spade, secateurs or shears, I’d fight my way in. And at 11 p.m. I’d emerge, exhausted and delighted, and with even more ideas. And I’d do it all over again on Sunday.

And in January 2020 I resolved to take things further. Paul Smyth came round and built some compost heaps, I hired a digger, the last of the lawns went and half the garden was once again a mess waiting for another year of weekends. Paul had begun to work with me a few years ago after four years at the world-famous Crûg Farm nursery in North Wales. He had great plant knowledge and was good with a spade.

And then came Covid-19. Like everyone else, I was isolated at home from mid-March, with nothing to do but garden. On 18 March I met Paul at a motorway service station. We were planning more work in my plot and for a garden at the 2021 Chelsea show. But things were different. There was no shaking of hands and no seats or tables in use, so we chatted over the bonnet of my car. A few hours later, back at home, I called Paul. The weather was great and there was something we could do during this lockdown period. Over the past few years the picture-sharing app Instagram had become an inspiration. Gardeners from everywhere shared photos, videos and information about plants and their plots and chatted to each other.

And so ‘Garden Conversations’ started that evening; a daily 7 p.m. broadcast from my home design studio and Paul’s Carlow potting shed. We’d play records on vinyl, drink coffee and have the craic. It was like pirate radio for green-fingered geeks. Each evening I popped an iPad on the desk and called Paul or other gardening friends – Rory in Galway, Darragh in Rathfarnham, Mark in London. Their faces would pop up on the screen and an audience began to build. In the tens at first, then hundreds, and then by the thousand. We undertook masterclasses on design, planting and the crafts of gardening. Our audience became a tribe, gathering each evening, chatting, laughing, joking, learning and slagging.

We answered thousands of questions, played our music, called up gardeners from around the globe. We had competitions: gardening quizzes that were impossible to win, and a contest for best floral hat, judged by Paul Costelloe, which brought tons of entries.

Soon gifts started to arrive at my house – chocolates, cakes and even record collections. A community was building of people who liked plants and gardens and who appreciated having an hour of each day to escape.

The broadcast has now moved on to an irreverent weekly gardening podcast called Dirt and we hope Gardening Together becomes a companion to that.

Paul’s story

Gardening and propagation wasn’t exactly a calling from birth, but something that has evolved over time into a major interest. I grew up on the family farm in Carlow in rural south-east Ireland, and veg-growing was my first passion – it’s a great introduction to gardening, a fantastic way both to learn and build confidence in propagation.

I studied at Waterford Institute of Technology. On the first day I only wanted to know how to grow veg; but by the end of the three years, and having been immersed in plant identification, husbandry and propagation, I had a very different outlook.

I spent a year working for Irish landscape architect and gardener Angela Jupe in her garden, Bellefield. There, my interest in plants escalated, as did my fascination with propagation. On one of my last days there Angela mentioned twin-scaling – it’s a propagation method for bulbs. (It basically takes advantage of a bulb’s defence mechanism, which kicks in when they are damaged. In fact, a lot of propagation uses this basic principle.) I was intrigued, and the conversation led to me doing two research projects as part of my degree.

I left Ireland for Evolution Plants in Wiltshire to work on a giant snowdrop collection, of all things! It was my responsibility to record, organise and then propagate, ready to launch a snowdrop mail order nursery. I spent months indoors chopping up bulbs in a semi-sterile environment, creating 50,000 snowdrops.

On a rare day off I went to the Grow London show in Battersea Park and came face to face with Sue from the renowned Crûg Farm nursery. I soon found myself on a dark bank-holiday Monday evening wending my way along the A5 and into the heart of Snowdonia to join their team. As the landscape got wilder and the houses fewer I asked myself what on earth I was doing.

My time at Crûg was definitely when my plant knowledge was tested, honed and vastly improved. I started as the gardener and progressed eventually to propagator, and within a year I was giving tours, listing off unpronounceable plant names to equally perplexed visitors. The collection of plants at Crûg is incredible and the variety impressive. When I took over the propagating job, the responsibility of the potted stock came with it, as did the realisation of the complexities of managing such a unique collection. The most exciting (and equally terrifying) part was the challenge of propagating this collection, many of which weren’t in cultivation – quite often when I consulted propagation manuals the plant name wasn’t listed and, in some rare instances, neither was the family!

Back to basics is the answer in this case. Observing growth habits, type of growth and timing are all important. As is experimentation and just taking a chance. In some cases this is easily done, but you are often faced with a plant that yields one cutting a year, so an educated guess needs to be well calculated. But that, for me, is the joy of propagation. The experimentation aspect and the thrill of cracking a particularly hard plant is what keeps me going. I was known to occasionally (when something went particularly right) run excitedly into Crûg’s office with the rooted or germinated plant in hand.

When you hold in your hand the largest known population of a particular plant outside its native habitat, it humbles you, but it also reminds you of the importance of plant propagation and the skill that you are mastering, as well as the importance of getting that information into the public domain so that everyone can benefit from it, particularly the people in the country where the material originated from. My favourite part of the job was talking to other propagators, sharing tips and solving problems.

Since leaving Crûg to work with Diarmuid I’ve missed the experimentation and the challenges, but my new role has allowed me to use plants in gardens, following them to maturity, not just focusing on producing them. My own gardening style is what I like to describe as benign neglect, though others might call it negligence. Either way, it means that what I grow is reliable and tough. I’m a believer in leaving plants to their own devices and not getting too worried about weeds.

I’ve been fortunate enough to garden in a few different places, primarily in my parents’ garden in County Carlow, where the snowdrops steal the winter show and the cottage-garden plants spill onto the paths in the summer.

In North Wales, on the periphery of Snowdonia National Park, where I lived and gardened for a few years, I have a steep garden at the back of a miner’s cottage. It too is stuffed with plants mostly left to their own devices.

Plants are my thing. I’m fascinated by how and why they grow, what they do, how they look and how we can grow them in our gardens. Picking a favourite is impossible, so through the course of this book I’ve picked a favourite plant for each month, some more ordinary, others some of the most extraordinary plants I’ve come across. All can be grown on these islands, and all will inject a little magic into your garden in that particular month.

When faced with that initial trip to a garden centre the best advice I can offer is to always be prepared and take a list. Even if you don’t stick entirely to your list, it will remind you what you can buy and what you need. And you’ll always come back with more than you bargained for. That’s one of the many joys of gardening … depending on whom you ask!

I’ve been lucky enough to do a job I love, and in this book I hope to share some of what I’ve learned. Gardening is a profession that’s as much about the process as the end result. I love the seasons and the fresh start every new year brings. This book sets out what to do on a month-by-month basis, picking relevant topics each month to hopefully inspire you to get out into the garden.

Helleborus argutifolius with a winter sprinkling of frost.

January

January is a shitshow. Christmas is over and there’s a dearth of joy. Daylight hours are in short supply and there is really very little appealing in the garden. If you go out and take a look you might find a few beauties making themselves seen or creating a scent in your plot; but if you actually attempt to do anything in the garden this month you can do more harm than good. The garden is best viewed from a window. So, book an Airbnb in Florida, eat fries and watch movies.

January is, however, a great month to consider planting – and maybe to plant. Provided the weather plays ball, almost any type of plant and style of planting scheme can be planted.

Weather is important because of the effect it has on our soil. If it’s a wet winter the ground can be waterlogged. If it’s extremely cold the soil may be frozen or covered in snow. Cold weather, including frost and lingering snow, can cause the water in plant cells to freeze, which damages the cell walls. Frost-damaged plants may become limp, blackened and distorted. Some leaves that are suffering from frost damage take on a translucent appearance. Frost in the soil has a more serious effect on plant roots. Prolonged periods of extreme cold can restrict the ability of roots to take up moisture and the plant may die. So be careful. But if the soil turns easily, and the temperature is above freezing, it’s a great time to plant.

Winter shot of Diarmuid’s garden.

Rhododendron covered in snow.

Frost on Lonicera nitida leaves.

Planting a garden

We’re going to look at different types of plants for each month of the year, kicking off with the most important group – trees.

All plants breathe life into a garden and every level of planting has a role to play: perennials for colour, contrast and filling the spaces in the soil; shrubs to create boundaries and structure, to mask unsightly things and to frame others; and trees to add the final dimension – to draw the outline, to create cover and add focal points like nothing else can do.

Trees provide a huge number of benefits to your individual ecosystem and to our wider one. They are aesthetically beautiful, they remove and store carbon from the atmosphere, they reduce the risk of flooding through slowing the effects of heavy rain, and their roots bind soil together, reducing the occurrence of soil erosion. The physical weight of a tree consists of approximately 50 per cent carbon and they enhance our air quality enormously by absorbing pollutants through their leaves and trapping and filtering contaminants in the air. They also produce oxygen through photosynthesis.

When planning a plot it’s important to make the best possible choice of trees. Choose a type or a group that will grow happily in your garden’s natural conditions and within the available space. Take a look at your garden and imagine the journey through the space. Begin to consider where trees should go, what type they should be, what roles they will play. Think about which trees you love. As part of an overall plan trees may be punctuation points, beautiful forms that lead your journey, indicating where to stop and rest and signposting where to look next. They may be the guardians that enclose the space or the shining stars that create the main interest.

Before acquiring a tree, research the options you’re considering. Explore your site and your soil and select something that you know will mature into a great specimen. You need to know the eventual height and spread of a tree before you plant it, even more so if you intend to position it in your front garden or near the house. You have a responsibility to ensure that the tree will not become a danger to the general public (branches could fall on passers-by or even onto the road), that it will not start to undermine the foundations of the house and that it won’t take over your garden.

Small to medium-sized gardens

Always find out from the nursery, garden centre or label what the eventual height and spread of the tree will be. If there’s no space in your plot for spreading branches, there are plenty of fastigiate or columnar trees – these are tall, slim beanpoles that will reach for the sky and not your boundaries.

Similarly, if you don’t want a tree that’s going to dominate through its height, there are many beautiful low-growing trees to choose from. So whether you are vertically or horizontally challenged, need a specimen in a lawn or something nice for a pot on a balcony, there are lots of interesting choices available. Here are our favourite trees for small to medium-sized gardens.

Cercis canadensis‘Forest Pansy’

The eastern redbud is native to North America and the state tree of Oklahoma. Gorgeous magenta pink flowers open in great profusion on bare stems in spring, followed by wonderful heart-shaped leaves in reddish, purplish-wine colours, and then by a colourful autumnal display. Its eventual height will be about 7.5 metres. Plant as a stand-alone specimen to be admired.

Blooms of Cercis.

Cherry tree in full blossom.

Styrax japonicus(Japanese snowbell)

Laden with very pretty, fragrant white bell-shaped flowers in spring, this is a tree whose show is best admired from underneath, so, for example, a bench placed underneath the tree would make an ideal viewing spot in the early summer. Prefers a sheltered spot. Eventual height and spread around 7.5 metres.

Liquidambar

Liquidambar, or sweetgum, is a majestic tree, reaching in maturity over 20 metres in height. It produces one of the best autumnal displays, with its five lobed leaves, a bit like a maple, that turn purple, crimson and burgundy. If you love this tree but, like most of us, don’t have the space to grow it, an alternative is ‘Gumball’. This is a dwarf, shrubby version of the tree – it is also sometimes grafted onto a standard stem to create a lollipop shape. It will grow to around 3 metres in height over time, with a compact rounded head.

Arbutus unedo(strawberry tree)

Arbutus unedo is a beautiful small evergreen tree with much to recommend it all year round – glossy green leaves, a light, luxuriously mahogany-coloured bark, small white urn-shaped flowers and a strawberry-like fruit. As the fruit are formed from last year’s flowers, you will often find them and the flowers at the same time, which is highly unusual. Combined with an interesting growth habit, this tree makes a great specimen and grows well in both dry and heavy clay soils, and it tolerates pollution, so it thrives in the city. For extra bijou gardens, there is a dwarf version – ‘Compacta’.

Cornus controversa‘Variegata’ (wedding-cake tree)

This is a lovely ‘centre of the lawn’ tree. Branches grow in a layered fashion, similar to the tiers of a wedding cake, giving rise to its common name. Leaves are green with creamy-white margins, turning yellow in the autumn.

Ornamental cherry

The tall, slim Prunus ‘Amanagowa’ grows no wider than 2.5m and usually no taller than 6m. Cheal’s weeping cherry (Prunus ‘Kiku-shidarezakura’) grows to around 3 metres and is covered in double pink flowers come April and May. These Fuji cherries are suitable for container growing and small spaces and are the epitome of Japanese delicacy with soft early spring blooms and a blaze of autumnal foliage colour. For a dazzling flourish of brilliant colour to cheer you up in February, choose the flowering apricot Prunus mume ‘Beni-chidori’. This has deliciously almond-scented deep pink blossoms on bare stems. Paul’s choice is Prunus incisa ‘Kojo-no-mai’. While more a shrub than a tree, it has all the beauty of ornamental cherries but reaches no more than 2.5 metres in height. Slow growing, but worth the wait.

Cornus kousa‘Miss Satomi’

Cornus kousa ‘Miss Satomi’ is a good choice if you have room for a tree to spread laterally but you just don’t want it to grow tall. Most of us are familiar with the colourful stems of dogwood (Cornus) in winter, but ‘Miss Satomi’ is better known for her deep pink flowers. The branches are outstretched and the leaves turn purple and deep red in autumn. It could also be fan trained against a wall, which is a good way of incorporating trees and shrubs into small spaces.

Acacia dealbata(mimosa)

Acacia dealbata, also known as mimosa, has beautiful silvery fern-like foliage that flower arrangers love and is covered in January with yellow pom-pom flowers that have the most delicious fragrance. It can be slightly tender, especially when young, although it seems to get hardier with age.

Azara microphylla

The flowers of this tree have a gorgeous vanilla scent from tiny greenish-yellow flowers produced in late winter and early spring. It’s a small evergreen shrub or tree with small dark-green leaves and will tolerate some shade.

Pyrus salicifolia‘Pendula’ (weeping pear)

The weeping pear is a pendulous small tee with soft mint-green leaves. It’s a really pretty tree that makes an elegant focal point in the centre of a lawn or gravel area where it can be admired.

Crataegus laevigata‘Paul’s Scarlet’

A compact hawthorn that is covered in crimson flowers in the late spring and early summer. A great tree if your garden is less sheltered. And it’s called Paul!

Crataegus laevigata ‘Paul’s Scarlet’.

Crab apple in midwinter.

Acer griseum(paper bark maple)

You’ll never tire of the wonderful coppery peeling bark of this maple. In addition, it puts on a good autumn display of red and orange. It’s a medium-sized tree, but slow growing, so it won’t take over anytime soon. Like lots of acers, it does best in a garden with shelter from the coldest winds.

Malus‘Evereste’

Crab apples make fantastic trees for a small garden. They can easily tamed be and aren’t huge even when they reach full maturity. They are covered in a profusion of blossom in spring and followed in the autumn and early winter by the most amazing fruits that look like Christmas baubles. ‘Evereste’ has red, flushed-orange to yellow fruits in winter and keeps a conical shape. Very adaptable to windy sites too.

Topiary

Shrubs and trees which can be tightly clipped into topiary shapes are always good candidates for the small garden. Laurel, bay, yew, holly, Lonicera nitida and privet can all be transformed into neat lollipops, pyramids or other shapes and kept to size with a regular pruning regime. They are best suited to a formal-style garden and work well in front gardens.

Examples of different types of topiary in London nurseries and gardens.

Beautiful tree bark

DIARMUID

The bark of a tree often looks its best when its dressing of leaves has fallen away. Many deciduous specimens show off their bark armour in January. Outside the garden, in bogs or on hills, I love to observe the beauty of a self-seeded tree, with bark bared and stems shaped and pruned by the wind.

While we’re in January, let’s take a moment to consider bark. Winter reveals all – it takes away the drapes and the clothing and it shows that if considered choices have been made at the time of planting, a tree’s bark can be as enticing and entertaining as its foliage or flowers.

Betula utilis var. Jacquemontii or the Himalayan white birch has the most brilliant white bark that shines in the winter; there are other specimens whose barks are outstanding too.

Prunus serrula, the Tibetan cherry tree, has a glossy coppery brown bark that is revealed when the old bark has peeled off – so shiny you want to reach out and touch it.

Another wonderful species is Acer griseum, known as the paperbark because its chestnut-coloured bark flakes away gradually like sheets of paper to reveal a stunning deep orange to red bark underneath.

The Cyprus strawberry tree, Arbutus × andranchnoides, also has peeling bark in cinnamon red colours.

Sometimes it is the twisted silhouette of a bare stem that draws the eye – corkscrew willow (Salix matsudana ‘Tortuosa’) and twisted hazel (Corylus avellana ‘Contorta’) are both beloved of florists for their spiralling, curling stems.

The red dogwood (Cornus stolonifera) and yellow-stemmed cornus don’t draw much attention to themselves during the year, but following their annual striptease they will add vibrant colour to the winter garden.

Acer palmatum ‘Bloodgood’.

Natural bonsai in Snowdonia.

Paul’s garden in the winter light.

Top tips for planting bare-root trees in January

Buy your trees as young as possible; they will adapt quickly to your situation.

—

Don’t let roots dry out. Have some damp hessian nearby to keep them covered.

—

Have some compost and slow-release fertilizer at hand to give the trees a strong start.

—

Plant to where there is a soil mark on the stem – not higher, not lower.

—

This can be a windy time of the year, so use a stake and tree ties. Put the stake in the planting hole before you plant the tree so that you do not pierce the roots.

—

Choose tree ties that are expandable, so they don’t strangle the tree. Loosen these ties as the tree grows. Check them every six months. You should be able to remove them in two years.

—

Plant singly or in groups, depending on what you are trying to achieve.

—

Don’t plant in extreme frost because the soil can crack and lift, exposing the roots. You want your trees comfortably bedded in for spring growth.