General Edward Porter Alexander at Second Manassas: Account of the Battle from His Memoirs E-Book

Edward Porter Alexander

1,82 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Krill Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 89

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

GENERAL EDWARD PORTER ALEXANDER AT SECOND MANASSAS: ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE FROM HIS MEMOIRS

Edward Porter Alexander

FIREWORK PRESS

Thank you for reading. In the event that you appreciate this book, please consider sharing the good word(s) by leaving a review, or connect with the author.

This book is a work of nonfiction and is intended to be factually accurate.

All rights reserved. Aside from brief quotations for media coverage and reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form without the author’s permission. Thank you for supporting authors and a diverse, creative culture by purchasing this book and complying with copyright laws.

Copyright © 2015 by Edward Porter Alexander

Interior design by Pronoun

Distribution by Pronoun

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 10: Cedar Mountain

Chapter 11: Second Manassas

General Edward Porter Alexander at Second Manassas: Account of the Battle from His Memoirs

By

Edward Porter Alexander

General Edward Porter Alexander at Second Manassas: Account of the Battle from His Memoirs

Published by Firework Press

New York City, NY

First published 1904

Copyright © Firework Press, 2015

All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

About Firework Press

Firework Pressprints and publishes the greatest books about American history ever written, including seminal works written by our nation’s most influential figures.

INTRODUCTION

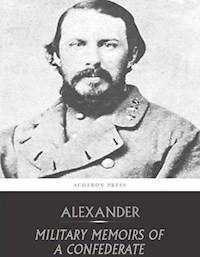

IN THE NARRATIVE OF THE Civil War, Edward Porter Alexander has loomed larger in death than in life. Just 25 years old when the war broke out, Porter Alexander had already served as an engineer and officer in the U.S. Army, but the native Georgian resigned his commission in May 1861 and joined the Confederacy after his home state seceded.

Porter Alexander spent 1861 as an intelligence officer, and he served as part of a signal guard, but he soon became chief of ordnance for Joseph Johnston’s army near Richmond. Half a year later, Johnston would be injured during the Peninsula Campaign at the Battle of Seven Pines, after which he was replaced by Robert E. Lee. Over the course of 1862, Porter Alexander took on more roles in the Army of Northern Virginia’s artillery branch, particularly under Longstreet’s 1st Corps.

Though he had served with distinction during the Civil War, it was Porter Alexander’s memoirs that have kept his name alive today. Though many prominent officers on both sides wrote memoirs, Porter Alexander’s were among the most insightful and often considered by historians as the most evenhanded. With a sense of humor and a good narrative, Porter Alexander skillfully narrates the war, his service, and he isn’t afraid to criticize officers, including Lee, when he thought they had made mistakes. As a result, historians continue to rely heavily on his memoirs as a source for Civil War history.

This account of the campaign that culminated with the battle of Second Manassas comes from Alexander’s memoirs, Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative.

CHAPTER 10: CEDAR MOUNTAIN

Recuperation.

— GENERAL POPE ARRIVES. — general Halleck Arrives. — McClellan recalled. — Lee moves. — Jackson moves. — Cedar Mountain. — the night action. — Jackson’s ruse. — casualties.

The close of the Seven Days found both armies greatly in need of rest. Lincoln called upon the governors of the Northern States for 300,000 more men, and bounties, State and Federal, were offered to secure them rapidly. They were easily obtained, but a mistake was made in putting the recruits in the field. They were organized into entirely new regiments, which were generally hurried to the field after but little drilling and training. President Davis also called for conscripts, — all that could be gotten. No great number were obtained, for those arriving at the age of conscription usually volunteered in some selected regiment. Those who were conscripted were also distributed among veteran regiments to repair the losses of the campaign, and this was done as rapidly as the men could be gotten to the front. Although this method allowed no time for drill or training, yet it was far more effective in maintaining the strength of the army than the method pursued by the Federals.

During the short intermission from active operations, something was accomplished, too, to improve our organizations, though leaving us still greatly behind the example long before set us by the enemy. Longstreet and Jackson were still but major-generals commanding divisions, but each now habitually commanded other divisions besides his own, called a Wing, and the old divisions became known by the names of new commanders. Thus, Jackson’s old division now became Taliaferro’s, and Longstreet’s division became Pickett’s, while Longstreet and Jackson each commanded a Wing, so called.

It was not until another brief rest in October, after the battle [176] of Sharpsburg, that Longstreet and Jackson were made lieutenant-generals, and the whole army was definitely organized into corps. Some improvement was also made in our armament by the guns and rifled muskets captured during the Seven Days, and my reserve ordnance train was enlarged. Lines of light earthworks were constructed, protecting Chaffin’s Bluff batteries on the James River, and stretching across the peninsula to connect with the lines already built from the Chickahominy to the head of White Oak Swamp.

Gen. D. H. Hill also constructed lines on the south side of the James, protecting Drury’s Bluff and Richmond from an advance in that quarter; and Gen. French at Petersburg, as already mentioned, threw lines around that city, from the river below to the river above.

Just at the beginning of the Seven Days Battles, President Lincoln had called from the West Maj.-Gen. John Pope, and placed him in command of the three separate armies of Fremont and Banks, in the Valley of Virginia, and McDowell near Fredericksburg. The union of the three into one was a wise measure, but the selection of a commander was as eminently unwise. One from the army in Virginia, other things being equal, would have possessed many advantages, and there was no lack of men of far sounder reputation than Pope had borne among his comrades in the old U. S. Army. He had spent some years in Texas boring for artesian water on the Staked Plains, and making oversanguine reports of his prospects of success. An army song had summed up his reputation in a brief parody of some well-known lines, ‘Hope told a flattering tale,’ as follows:—

Pope told a flattering tale,

Which proved to be bravado,

About the streams which spout like ale

On the Llano Estacado.

Pope arrived early in July and began to concentrate and organize his army. A characteristic ‘flattering tale’ is told in an address to his troops, July 14, dated ‘Headquarters in the Saddle’:—

‘Let us understand each other. I come to you from the West where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose [177] business it has been to seek the adversary, and beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defence. . . . I presume I have been called here to pursue the same system, and to lead you against the enemy. . . . Meantime, I desire you to dismiss from your minds certain phrases, which I am sorry to find so much in vogue amongst you. I hear constantly of “taking strong positions and holding them” ; of “lines of retreat,” and of “bases of supplies.” Let us discard such ideas. . . . Let us study the probable lines of retreat of our opponents and leave our own to take care of themselves. . . . Success and glory are in the advance. Disaster and shame lurk in the rear. . . .’

The arrogance of this address was not calculated to impress favorably officers of greater experience in actual warfare, who were now overslaughed by his promotion. McDowell would have been the fittest selection, but he and Banks, both seniors to Pope, submitted without a word; as did also Sumner, Franklin, Porter, Heintzelman, and all the major-generals of McClellan’s army. But Fremont protested, asked to be relieved, and practically retired from active service.

Meanwhile, after the discomfiture of McClellan, Mr. Lincoln felt the want of a military advisor, and, on July 11, appointed Gen. Halleck commander-in-chief of all the armies of the United States, and summoned him to Washington City. Ropes’s Story of the civil War thus comments upon this appointment: —

‘It is easy to see how this unfortunate selection came to be made: Halleck was at that time the most successful general in the Federal service; it was perfectly natural that he should be the choice of the President and Secretary of War, to whom his serious defects as a military man could not have become known. His appointment was also satisfactory to the public, for, as so much had been effected under his command in the West, he was generally credited with great strategic ability. . . . But both the people and the President were before long to find out how slender was Halleck’s intellectual capacity, how entirely unmilitary was the cast of his mind, and how repugnant to his whole character was the assumption of any personal and direct control of an army in the field.’

Halleck arrived in Washington and took charge on July 22. He found, awaiting for his decision, a grave problem. It was whether McClellan’s army, now intrenched at Westover on the James, should be heavily reenforced and allowed to enter upon another active campaign from that point as a base, or whether it should abandon the James River entirely, and be brought [178] back, by water, to unite with the army now under Pope, in front of Washington.

McClellan earnestly begged for reenforcements, and confidently predicted success if they were given him. He had begun to appreciate the strategic advantages of his position, and he was even proposing as his first movement the capture of Petersburg by a coup-de-main