4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Myriad Editions

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

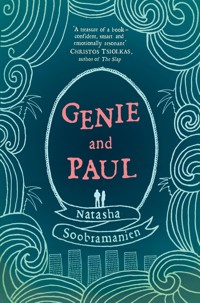

One morning in May 2003, on the cyclone-ravaged island of Rodrigues in the Indian Ocean, the body of a man washes up on the beach. Six weeks previously, the night Tropical Cyclone Kalunde first gathered force, destruction of another kind hit twenty-six-year-old Genie Lallan and her life in London: after a night out with her brother she wakes up in hospital to discover that he's disappeared. Where has Paul gone and why did he abandon her at the club where she collapsed? Genie's search for him leads her to Rodrigues, sister island to Mauritius - their island of origin, and for Paul, the only place he has ever felt at home. Will Genie track Paul down? And what will she find if she does? An imaginative reworking of the French 18th century classic, 'Paul et Virginie', set in London, Mauritius and Rodrigues, Genie and Paul is an utterly original love story: the story of a sister's love for a lost brother, and the story of his love for an island that has never really existed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

For my mother and father

‘Apparently, there has been only one prominent event in the history of Mauritius, and that one didn’t happen. I refer to the romantic sojourn of Paul and Virginia here.’

– Mark Twain, Following the Equator

‘All the previous editions have been disfigured by interpolations, and mutilated by numerous omissions and alterations, which have had the effect of reducing it from the rank of a Philosophical Tale, to the level of a mere story for children.’

– Publisher’s note for Paul and Virginia, by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, English translation, c.1851

‘I have seen Europe from Mauritius, now I will see Mauritius from Europe.’

– Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Journey to Mauritius

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

PROLOGUE

GENIE

PAUL

PAUL AND GENIE

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

About the Author

Copyright

PROLOGUE

On the afternoon of Saturday 3rd May 2003, twelve-year-old Jeannot Gaspard set out from home on his bike to visit a new friend. He did not tell his mother where he was going. Jeannot’s friend lived in a shack at the end of a spit of land on the west coast of Rodrigues – the wilder side of the island – a few kilometres away from the village of La Ferme, where Jeannot lived. The journey took longer than it might have done: the destruction caused by Cyclone Kalunde which had brushed past the island two months previously was still being cleared, parts of the road impassable due to reconstruction work, and, once Jeannot had turned off onto a track down to the beach, much of it was blocked by fallen trees. When he arrived at what he guessed was his friend’s shack, his friend was not there.

Jeannot’s visit was prompted by a conversation he’d overheard between his mother and uncle. Jeannot had come to warn his friend, and to ask him some questions. He waited, but his friend did not appear. The following day, Jeannot returned to the shack and again waited, without luck. Having noted on his first visit the exact state of disarray in which a heap of blankets had been left, Jeannot concluded that his friend had not slept there for two nights. When, on Monday (Jeannot having skipped school), there was still no sign of him, Jeannot finally allowed himself to investigate the contents of the small cardboard suitcase left in a corner of the shack, seeking some possible clue to his friend’s fate or whereabouts. The unlocked suitcase, on which was painted in pink pearly nail polish a girlishly curly ‘G.L.’, contained, along with a bundle of clothing, the following items of interest:

– a washbag containing various men’s toilet articles, including a razor, a jumbo tub of chewable vitamin C tablets which felt half-full when shaken, plus, rather excitingly, some condoms;

– a passport bearing a photo of his friend with a shaved head, looking some five years younger, giving his date of birth as 9th March 1971 and his place of birth as Mauritius;

– a wallet containing a 500-rupee note, a map hand-drawn on the back of a blank betting slip on which was marked a cross and the name ‘Maja’, and a strip of photos showing two teenage girls pulling stupid faces – the younger one dark-skinned with curly blue-black hair, the older pale, with heavy-looking dark red hair;

– an overwashed T-shirt bearing a faded, screen-printed tropical island in blue silhouette, superimposed over an orange sunset – much like the ‘Rodrigues’ T-shirts for sale in the tourist shops in Port Mathurin, except on this one was written ‘The something Band’;

– an old-looking edition of Paul et Virginie by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, in poor condition, with pages missing.

Four days later, the owner of these items was found washed up on the shore by Pointe du Diable, several kilometres down the coast from where he had spent the last two weeks of his life. When his suitcase was discovered in the abandoned shack soon afterwards, it contained all the above-mentioned items – except for the book, which Jeannot Gaspard still has in his possession.

GENIE

(i) The Cyclone

On Saturday 8th March 2003, Intense Tropical Cyclone Kalunde peaked to a Category Five in the middle of the Indian Ocean, southeast of the island of Diego Garcia, reaching sustained winds of a hundred and forty miles per hour. At that same time, almost six thousand miles away in the middle of London, twenty-six-year-old part-time postgraduate student in housing studies Genie Lallan was being rushed into hospital.

While Genie lay unconscious in intensive care, Kalunde travelled eastwards, sideswiping Rodrigues – little sister island of Mauritius, which narrowly escaped – wreaking destruction but claiming no lives, before veering southwards four days later towards the colder latitudes of the southern Indian Ocean, and oblivion.

At which point Genie Lallan, still in London and still in hospital, opened her eyes.

This was not the first time Genie had woken up without knowing where she was. Or even the first time she’d woken up in hospital, if being born was a waking-up of sorts. But it was the first time she’d died and come back to life again.

She’d only died technically. You could say the same about her resurrection: Mam took photos of her hooked up to the wires and drips, and some of the fat pipe forcing breath down her throat, a mechanical umbilical cord. Mam took the photos to show Paul, Genie’s big brother, who had been with her the night she’d almost died.

Where is he? Genie mumbled, not yet properly awake.

Mam said nothing, only smoothed the hair away from Genie’s forehead.

She was discharged and taken back to Mam’s. Her room had not changed since she’d left at eighteen. Walls the same colour. A flaky pink like dried calamine lotion – no, like the pink of something else which she could not quite recall, she thought, resurfacing between naps – with picked-off scabs where there had once been posters. Hazy from medication, Genie turned her attention to a picture on the wall by her bed. A plate taken from an old book. Paul et Virginie. A book with engravings she’d liked so much as a kid, she’d surreptitiously bent back the spine to precipitate its gradual falling apart so she could release that picture. ‘Le Passagedu torrent’. Against a background of black mountains, a muscular youth stripped to the waist, trousers rolled up to his knees, was standing on a rock in the middle of a swollen river, poised to continue his treacherous crossing. A girl, about the same age, on his back, clinging to him, arms around his neck, had her face half buried in his hair. On the riverbank were banana trees whose broad serrated leaves flapped in the wind – the same wind which was whipping the river into a frenzy of white froth; the same wind which had unfurled the girl’s hair from the scarf she had used to tie it back. The girl looked afraid but the boy, smiling up at her, looked happy to be carrying this load, which seemed to give him the strength to carry on.

Genie studied its cross-hatchings minutely for the rest of the afternoon, in between sleep, until Mam entered with a tray. When she drew the curtains, the sunlight was sharp and watery.

There’s been a cyclone, Mam said. She had rung the home where Grandmère lived for her regular update and they’d told her. Mauritius was fine, they said, but Rodrigues was devastated. Absolutely devastated.

Genie squeezed lemon into her bowl of chicken noodle soup. Its velvety steam swabbed her nostrils. Devastated, she thought. Shellshocked. Crying. In bits. She asked again about Paul. Where was he?

Mam shrugged. Are you going to eat that soup or just blow on it?

On her bed were the same sheets she’d had as a child. Deep-sea divers in old-style diving bells waded heavily through a faded violet sea, parting weeds to find chests spilling treasure. When Genie had first started her periods, she’d bled on them and the stains had looked like rusted coins. She hadn’t seen these sheets in a while, she realised, as she manoeuvred herself out of bed. It was the same bed she’d always had. She had little strength to negotiate its sagging and felt tempted to let herself be swallowed up in its peaks and troughs. Being back at home was a bit like that. But she was here only temporarily. She couldn’t imagine how it must feel for Paul, who had no foreseeable way of finding anywhere else to live. After his last eviction he had told her that he was done with squatting, that he no longer had the energy to make himself anew. A quote from something, Genie supposed, palm against the wall as she struggled to her feet. Weak as she was, she had to go to his room; she had to see for herself.

Genie knew as soon as she pushed open his door, as soon as she saw how he’d left his room. How he had left: drawers pulled from their sockets, gutted; shelves cleared in one swipe – all of it gone, even the stupid photos of her and Eloise he’d stuck into a corner of the wardrobe mirror. Just the basics. ‘Prison possessions’, he called them. He was not lying low at all. He’d gone.

Genie opened the wardrobe; sunlight slithered the length of the mirror and fingered the wire hangers inside. They’d been picked clean.

Mam appeared in the doorway.

I couldn’t tell you while you were in hospital.

No, said Genie, I guess you couldn’t. Where is he?

But Mam said nothing, only walked to the wardrobe door and clicked it shut. Her reflection looked into Genie’s and Genie understood.

He never came to the hospital, did he?

No. His things were gone when I came home from my shift in the morning.

He’d taken Mam’s suitcase. The one they’d come to London with. But Mam told Genie not to worry, he would surely be back soon. If only because he’d run out of money.

(ii) 1981–82

Genie was five and Paul ten when Mam took them to live in London. They had never travelled on a plane before. They flew for hours over an empty grey desert. When Genie asked if this was London, Paul laughed.

You idiot. That’s the wing of the plane.

Some hours later, the captain announced their imminent landing.

That’s London, said Paul, sounding almost awestruck, forgetting for a moment how angry he was to be leaving Mauritius. His cheek was pressed to Genie’s at the window as the plane banked steeply. He pointed out the sticky webs of light below. Looks like God’s been gobbing.

Mam would normally have snapped at him for that malpropte, but she seemed not to be aware of anything around her. When the plane began to buck and shudder in anticipation of its landing, Mam seemed equally apprehensive, leaning further back into her seat, hands gripping the armrests, as though trying to resist the inevitable descent.

They were going to live with Mam’s family – Grandpère and Grandmère and Tonton Daniel. Genie and Paul had never met them before. They were leaving behind Genie’s dad, and Genie’s half-brother Jean-Marie, neither of whom had ever been to London. They were leaving behind Mauritius, the only place Genie and Paul had ever known.

Everything they brought with them had fitted in Mam’s suitcase. She kept it on top of the wardrobe in her new room. Mam’s was a gloomy room with only a narrow window, the curtains always half-drawn. It had been Grandpère’s until they arrived and it was still cluttered with his things: the back issues of Titbits magazine; the Teasmaid on the bedside table which Grandmère and Tonton Daniel had bought him for his birthday but which, to their knowledge, he had never used (No wonder, Paul had said, earning himself a slap around the ear, he only drinks rum and he never has to get up for work); the boxes and bottles of old medicines which crowded the ugly putty-coloured mantelpiece; and a stack of old books. Paul would spend hours absorbed in Titbits, but if he was feeling restless he would flick through Grandpère’s TeachYourself English, reading aloud.

Hello, Mrs Baker. Is Susan there? (Paul’s voice posh and mincing, with a heavy Mauritian accent.) Yes, Roger. Please come in. Susan! Roger is here to see you! Would you like a cup of tea, Roger? Yes, please, Mrs Baker, you old bag. You have a very nice home. But you stink of shit.

Or, if he was in a good mood and wanted to please Genie, he would adopt the voices of characters from the TV programme Bagpuss, which she loved. But again, some trace of Creole inflected his imitations of Professor Yaffle or the mouse organ mice, rendering his impressions satirical despite his sincere intentions. In return, to console Paul who seemed to miss Mauritius so much, Genie would ‘read’ aloud to him from Mam’s old copy of Paul et Virginie, making up stories around the beautiful engravings. And, since it was the book for which the two of them had been named, Genie would cast them both in the title roles. I can’t swim, said Genie, so you are carrying me across the river. We are running away from home. And my hair is very lovely.

There was Mam’s dressing table, too, crowded with things that Genie liked to look at, particularly the framed photo of Mam with Genie’s dad Serge outside their old house in Mauritius. Genie would marvel at the difference in their looks: Mam’s more various, the Indian skin, the Chinese bones, the Creole eyes and mouth, while Papa – Serge – was so dark-skinned that you could barely make out his features. Papa was hard to see in the photo in the way that he was getting harder and harder for Genie to see in her head. There were so many new things – new people – around her. Genie looked like Papa and Paul like Mam but also different – his hair and his skin and his eyes that same colour, but with maybe more of a glow. Like honey, Mam would say, almost proudly.

Once Genie asked where the photo of Paul’s dad was.

You can’t take photos of a ghost, Paul said.

Is he dead, then? Genie was impressed.

He is to me.

They lived in three rooms on the ground floor and basement of 40 St George’s Avenue, a narrow Victorian terraced house in Tufnell Park. The flat was not self-contained: to walk from one room to another involved stepping out into the corridor used by the other residents. Genie was shy of these strangers in their home, but Paul would try to engage them all in conversation – the young angle in the squirrel-coloured duffel coat who lived right at the top, or the old Chinese man (bonom sinwa, Grandmère called him). But these men seemed as timid as Genie was.

Genie and Paul’s play was shaped by the movements of the other members of their household: while Daniel was at poly or Grandmère was in the kitchen they would play in the front room, where the four of them slept; if Mam was at work they played in hers. And sometimes, if Grandpère was out, they would go down to the kitchen to watch television, or out into the garden. But Grandpère rarely went out. He sat at home all day in his chair in the kitchen, where he also slept, watching the horse-racing or the news and drinking rum. Grandpère, they thought, was gradually flaking away. His skin was grey-brown, dusty with a light white scurf like the bloom on old chocolate. Seeing him sober made him as foreign to Genie and Paul as hearing him speak in English. When he stood up he had the grand proportions of a monument, but when he walked he staggered like a man caught in a gale. The unpredictability of his movements frightened them.

So they spent a lot of time in that draughty hallway where once they had played in a garden in Mauritius. They would crunch into dust the dead leaves that had drifted in through the door, or play post office with the pile of mail for ex-tenants who had left no forwarding address. The hallway smelt of damp newspapers, the muddied doormat and the cold air from outside, spiked with the smell of Grandmère’s cooking drifting up from the kitchen.

Every morning, when the sun rose to a point where it set the orange walls on fire, Genie would leave the sofabed she shared with Grandmère and Paul and cross the prickly carpet to climb in with Daniel. They would lie there staring up at the ceiling as though contemplating the night sky and her heart would rise like a balloon. They had long, aimless conversations: she would ask him how thunderstorms happened, or why a chair was called a chair or what colour Paul’s dad was. Daniel would try to answer but Paul would shout, from the other side of the room, Because it looks like a chair.

Or, Don’t you talk about my dad.

Genie was sure for a long time that Daniel was Jesus with his long hair, his odd beauty (a different configuration from Mam’s: Chinese bones, Creole skin, Indian eyes – green eyes) and the righteous anger never directed at her but often used to protect her. In that way, Paul was like Daniel. As she and Daniel lay there, she stroked his smooth brown skin and tugged lightly at the hairs in his armpits, which were tough and silky like the fibres from the corn cobs Grandmère would strip and boil for them. She asked him if he would ever get married.

Oh, I don’t think so, he said. Maybe when I’m ninety.

She would have preferred him to say Never, but ninety seemed quite far away.

How old are you now? she asked.

Twenty-two. It takes a long time to count from twenty-two to ninety.

And then Genie offered to marry Daniel and he cordially accepted. Paul laughed nastily. He chucked aside his pillow and ran across the room, now barred with sunlight. He kicked Daniel’s bed and called Daniel a pervert. That was how it usually ended: with Paul getting angry and calling Daniel names. And then Daniel would say something like, Shut up, you little shit. And then Paul would go running to Mam’s room next door saying, Mam! Daniel said shut up you little shit. Then they would hear Mam sigh and rise heavily out of bed and come into the room and tell Genie to go down and ask Grandmère to make the porridge.

But Daniel had lied to Genie. Three months after they came to stay, he told them he was getting married.

It was his day off from the poly. He was taking them to the park.

Let’s go popom, Daniel said, rubbing his hands, Paul screwing up his face at this babyish expression. But still he raced to pull on his shoes. They walked past the knuckly, pollarded elms along St George’s Avenue, the pavement wet from recent rain but still crusted here and there with stubborn lumps of dog-shit. Swinging from Daniel’s hand, Genie pointed these out to him.

How helpful, he said. Thank you, Genie. You have a special doo-dar.

What are you on about? asked Paul.

A dog-do radar: a ‘doo-dar’. And then Daniel made a sound like a police siren – doo-dar! doo-dar! – which Genie repeated on pointing out further trouble-spots. Paul pulled up the hood of his anorak and, head down, hands deep in pockets, dropped back a few paces, even though he had no friends here to witness his shame.

It was on their way back from the park, after they had stopped off at the sweet shop, that Daniel broke the news. He was to marry a fellow student, Fanchette, in the spring. Strangely, it was Paul who was most upset. It was Paul – barely able to spit out the words around his jawbreaker – who accused Daniel of having lied to them.

A week before the wedding, Genie spotted a clutch of daffodils in a corner of the gloomy front garden, near the bins. It was the first time she had ever seen daffodils. She was shocked by their waxy brightness and pointed them out to Paul. Later that afternoon, while she was being fitted for the bridesmaid’s dress Grandmère was making, Genie heard the front door click. She looked out to see Paul in the garden, scavenging for the daffodils. She tried to run after him but Grandmère had her pinned in place.

Res trankil, ta.

She watched as Paul tugged them up, returning with an armful. He went into Mam’s room. She heard Mam tell him off.

You should leave beautiful things where you find them, Mam screamed at him. They’re all going to die now.

On the day of the wedding, Genie was given a book to carry along with her posy of pink and white silk flowers. It was a small prayer-book bound in white leather with silver-edged pages. Genie thought it as precious and mysterious as a spell-book. She asked Paul to read to her from it.

I am the Resurrection and the Life saith the Lord: he that praiseth my farts, though he were stinky, yet shall I kick him in the arse.

Grandpère did not make it to the ceremony, but was waiting for them at the hall when they arrived for the reception. He swung Genie around and she smelt the chemical smell of the special cream he applied to his flaking skin, which made her think of the kitchen. This was the first time that Genie and Paul had seen him outside it. He had appointed himself barman and was serving drinks at the trestle table in the hall. They took their seats at the top table without him. The tablecloths were decorated with marguerites and asparagus ferns. Mam fussed over them to make sure they were not wilting and, when Genie asked how the flowers had appeared there, Mam told her she had taken them from the garden and sewn them on herself.

Paul tugged at Mam’s sleeve.

But Mam, you said you should leave beautiful things where they were, or they would die.

What are you talking about? Mam snapped.

The daffodils! he cried, turning on his heels and running into the crowd of guests.

Shortly afterwards, when Mam was spooning biryani onto Genie’s plate at the buffet table, they heard a commotion at the other end of the hall. They saw Paul running away. He had bitten off the head of the bride figurine on the wedding cake. Genie was sent after him. She found him out in the corridor, by the kitchen, where she could hear shouting. Paul was peering through the glass of the kitchen door, and when Genie joined him she saw Grandpère slumped in a chair, long legs splayed out, with Daniel astride him, shouting into his face and gripping Grandpère’s wrists to restrain his wildly flailing arms: Grandpère was trying to hit Daniel. Paul turned on his heel and ran to the fire exit, where he pushed down the bar of the door, and left, slamming it shut behind him.

Back at the table, Genie noticed that champagne had been spilt on her little prayer book. The leather cover was buckled and stained and some of the silver had run from the edges of the pages. It was ruined. She put her head into Mam’s lap and sobbed. Mam gently pushed her aside, anxious for the silk of her new dress.

From that night on, everything was different. Daniel and Fanchette went to stay in a bedsit they had rented in Islington. Grandpère slept in Daniel’s bed. Paul and Genie were supposed to be asleep when Daniel and Fanchette’s brother brought him in. They staggered under the dead weight of him, a limp crucifix, and laid him on the bed. There was a businesslike tone to Daniel’s voice that Genie had not heard before.

Met li lor so kote, tansyon li vomi liswar. Put him on his side, in case he’s sick in the night.

After they left the room, Genie began to cry quietly.

You’d better get used to it, Paul said. She’d had no idea he was still awake. Something in his voice crackled like static. Daniel’s going to Canada with her.

Later that night, through Grandpère’s snores, Genie heard Paul cry. She slipped her hand into his. He did not push it away.

Some months after the wedding, they went to see Daniel and Fanchette off at the airport. At the Departures gate, Paul barely acknowledged Daniel, turning his back shortly after their goodbye hug. Back home, when Genie asked if he was upset that Daniel had gone, Paul was scornful.

He’s the one who should be sad. He’s leaving us. And then he said, I hate airports.

The next day, Grandpère came into the front room. He almost never came into the front room. Ale vini! Nu pe al promne! Come on, you lot! We’re going out!

Grandpère had never taken them out before. They trailed behind him, apprehensive about where he could be taking them. They crossed Junction Road to Tufnell Park tube station, descending in the lift and emerging onto the platform of the tube, which terrified Genie and seemed to her like being in the belly of a giant hoover.

They got out at Embankment and walked alongside the Thames, Paul leaning over every now and then to look down at the water while Grandpère swaggered some way in front, his long legs incapable of taking smaller steps to accommodate them. Eventually they saw him stop, and they caught up with him. Genie thought of Grandpère’s skin when she saw how the bark of the plane trees, which lined the river, flaked away.

Look, he said. Look at that. Grandpère was pointing to a great concrete column. Cleopatra’s Needle.

He read the plaque aloud in his stiff, heavily accented English but Genie understood little of what he was saying. She did not know who Cleopatra was. She did not know why she had left her needle here. She did not think it looked much like a needle. Genie looked at Paul but his face was turned in the opposite direction and she followed his gaze to a hot-dog stand across the road. Paul stared at it meaningfully, willing Grandpère to notice, his nose lifted to the breeze, sniffing it.

They might have been passing en route to somewhere else but the memory ended there, on the banks of the grey-brown Thames, the water churned up by the autumn wind, with Grandpère lurching around, his arms thrown wide, laughing. Ala en kuyonad kado, la! What kind of a bloody stupid gift is that?

Soon afterwards, he went into hospital.

The night Grandpère died, Genie and Paul lay awake in the dark for a long time. Then Genie felt a fierce little kiss planted on her cheek. It was more like a bite.

They were not afraid to go into the kitchen and watch television, after that.