Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

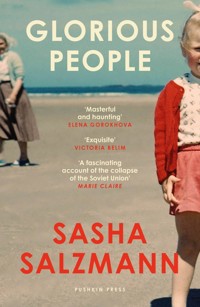

'A fascinating account of the collapse of the Soviet Union' MARIE CLAIRE 'Masterful and haunting' ELENA GOROKHOVA For Lena, childhood summers meant training to be a good socialist at Pioneer camp, singing songs in praise of Lenin. But when perestroika shatters her world, all must be unlearned. Lena's corner of the USSR is suddenly Ukraine: there is a McDonalds in Moscow's Red Square and certified foreign whisky, but no food in the shops. For her friend Tatyana, survival in her changing homeland requires new skills: bullet dodging, business sense and a knack for bribery and corruption. When both women head West in search of new beginnings, their homesickness for a vanished land is inherited by their rebellious daughters, caught between forging their own identities and untangling the rich histories of the mothers who raised them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 512

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

5

The author would like to thank the German Literary Fund for supporting their work on this book.

6

A Note on Place Names

Throughout my translation of the novel, I have used transliterations based on Ukrainian place names rather than on the old Soviet-era Russian names. For those parts of the novel set in the Soviet Union this is perhaps anachronistic, but it is now, rightly, common usage.

imogen taylor

9

Every made-up story is based on true events.

And if I want to be believed, I must get things wrong.

10

Contents

Skipping Stones

Of course i wanted to know what had happened, what exactly took place before Edi was beaten up in the yard. She was lying on the grass, her hair all pale and dirty. My mother was kneeling beside her, Auntie Lena was yelling at them both, and all three were waving their arms around like they were casting out evil spirits. When they saw me they started to cry, one after the other, like a Russian doll, the tears of one turning into the tears of the next, and so on. First my mum let rip, then the others joined in, as if they were singing a howling, wailing round. I couldn’t make head or tail of it.

OK, so it wasn’t hard to guess why my mum came over all misty-eyed when she saw me standing there after the long radio silence—but Lena and Edi? They seemed to have some score to settle. Mother and daughter, one of them lying on the ground like the other’s shadow, or the other way round: one of them growing up out of the other’s feet, like a shrub with broken branches. Auntie Lena was wearing a green trouser suit that hung loosely on her body; I almost didn’t recognize her. I’d worn her daughter’s babygros, sat at her kitchen table revising for tests and exams, rung her doorbell in the middle of the night when things got too much at home—but that was a long time ago and for a moment I wasn’t sure it was really Lena, standing there yelling at 12her cowering daughter: ‘Why were you hanging around out here? What were you doing?’

Edi looked the worse for wear but not drunk, though she claimed in all seriousness that she’d seen a giraffe in the yard, wandering around between the tower blocks, nibbling at the grass, peering in at windows. This may be the former East, but as far as I know we’ve no giraffes round here. You don’t get them in these parts.

She hadn’t been here long; you only had to look at her hair and clothes to know that—especially her clothes. I’d never seen much of Edi, even when she still lived with her parents and I did my homework at their kitchen table. I was too young for her, and anyway she never came in to make herself a sandwich or a cup of tea when I was around. The door to her room had a milky glass panel, and through this I could see her switch her light on and off for no apparent reason, day and night. On and off, on and off. Once, the glass was broken; only a few jagged shards stuck out from the frame. No one mentioned it and I asked no questions and soon there was a new pane of glass, as if nothing had happened. Edi was pretty unobtrusive back then—black hair, black jeans, black top. If I saw her on the street I’d walk right past her, she dresses so brightly now. I only recognized her because her mum was standing next to her, shouting at her. And because it was my mum trying to make the peace. Over and over they launched into the same string of reproaches, Auntie Lena saying furiously to my mother, ‘Why didn’t you tell me—?’ and my mother retorting, ‘It’s nobody’s business if I’m dying.’

Not a good moment for me to enter the fray; she was mid-sentence when she caught sight of me and she stiffened, as if time had sprung a crack. snap. She looks at me, I look at her.

Her hair’s gone grey and she had a crushed look to her, though she’d clearly made an effort with her appearance. She dyes her 13hair—has done for a while—and I dare say it had started out the evening neatly styled, but now it was straggly and dishevelled, and you could see the silver roots. The skin under her eyes sagged—but maybe that was because I was standing over her; everyone looks weird from that angle. She seemed small. Looking past the crown of her head, I could see her hands; there was dirt in the creases of her palms. She must have tried to pull Edi up on to her feet.

I wasn’t surprised she was in town. Uncle Lev had told me she’d be at the party at the Jewish Community Centre—in fact, he’d paid me an official visit to inform me and to demand a family reconciliation, a big reunion. He came in a clean shirt, his nostrils flaring; he had the best intentions, but I had to disappoint him. When he saw that he wasn’t getting anywhere, he tried to guilt-trip me—you can’t break with your own mother; you have to love her no matter what—but I don’t think I’m obliged either to love or not to love her; she’s my mother and that’s all there is to it. Things are what they are.

I’d gone out just because I felt like it that evening—wandered around, watched the evening strollers, nothing special. The streets smell different at dusk, sourer, and I like that, but this particular night I smelt burnt sugar and heard shouts, and I thought I’d go and investigate.

At first I was glad it wasn’t my mother lying beaten up on the ground—then I realized that was the extent of what I felt. Live. Leave me in peace.

It looked as if there had been a small fire here a short while ago; we were standing next to a heap of charred paper—crinkly, soot-coated bundles tied up with string—rather beautiful, actually. I seem to remember the smell of Coke and bitter caramel; it tickled our noses and made Auntie Lena sneeze. Whoever had tried to have a little picnic here between the tower blocks had either been 14driven away or had to leave in a hurry, but none of the women would tell me how Edi fitted in, or why half the Jewish community mishpocha were hanging out of the second-floor windows gawping at us. The women were crying, but they didn’t want to seem weak. That’s socialist manners for you—flaunt your wounded emotions, but try to keep a grip on yourself.

All around us were balconies with identical flags fluttering at their railings, as if the people who lived there would forget where they were if they didn’t have that little bit of cloth flapping in the wind. The funny thing is that for many of the residents—the ones I know, anyway—that flag has nothing to do with the emblems on their passports.

None of the women wanted to return to the party, but they couldn’t be left out in the yard either, Edi dirty and bleached and battered, Lena with her eyes puffy from crying, and my dishevelled mother who’d just announced that it was nobody’s business if she was dying. I asked them if they’d like to go back with me to freshen up and have a cup of tea. It seemed the right thing to do, to offer them a sit-down at my kitchen table. We walked quickly, without speaking, as if afraid of being followed. I could hear the rubbery squeak of my soles on the asphalt.

When we arrived, Auntie Lena made straight for the sink, held a flannel under the cold water and pressed it to Edi’s forehead. I flicked the switch on the kettle, ignoring my mum’s greedy looks, the way she stared at the sofa, taking in every crevice, as if to commit it all to memory. It was her first time here; she even looked lovingly at the open bags of crisps on the floor. I ignored, too, the hissing voice in my head telling me that the flat was small and dingy and dirty. The only free wall was covered by a massive Path of Exile poster with a dark, forbidding sky and spurts of blood. There was a smell of barbecue sauce from the box of chicken wings next to 15my keyboard. The curtains were drawn, the computer was on, battling nations zapped each other on the screen. The roar of the fan filled my lungs.

We said nothing for a while. I could tell that Mum’s hands were trembling because the tea in her cup was rippled, as if tiny stones were skipping across the surface, but her face was calm and her eyes big and round, as if she couldn’t believe she was seeing me. I couldn’t believe it either.

You shouldn’t criticize people for not being heroes, she had said the last time we’d argued—or maybe it wasn’t the last time; our arguing had neither beginning nor end, it was an unbroken chain of resentful mutterings. They weren’t even reproaches; they were just noise. But when I asked her why, if that was the case, she expected me to be someone I couldn’t be, she had no answer. She wouldn’t—or couldn’t—answer any of my questions. And she had no questions for me—still doesn’t.

She sat there with her silvery copper-beech hair alongside bleached Edi and her emerald-green mother, all three of them rocking their heads, ever so gently, almost imperceptibly, as if waves were coursing through their shoulders, as if electricity were running up their necks. The little stones continued to skip over the surface of the cooling tea, faster or slower, depending on their size—hop, hop, hop, sink.

We made an effort, talked a bit, exchanged coordinates—tentative words, clumsy dance steps. But not bad, considering.16

I

Reflections of bright faces on my palms.

Women and men from the 70s like dead planets illuminate the summer air.

serhiy zhadan, ‘This is how you stand for a family photo’ translated from the Ukrainian by John Hennessy and Ostap Kin18

The Seventies

Lena

From up close, the wall looked green. Lena knew that if she took just one step back, she would see the stripes and patterns of the wallpaper—fine black lines like flower stalks running crosswise from floor to ceiling. But she didn’t look up. Her mother had pulled her by the ear and planted her right here. Lena stared at the green patch; there was nothing else and the nothing made her eyes ache. She was bored and needed a pee; more than anything she was bored, but she’d sooner have burst than said a single word. She wouldn’t wet herself—she was too old for that, almost a schoolgirl—and she wouldn’t do her mother the favour of crying. Besides, she knew that Father would be home any minute; he would rescue her. He would shout at Mother for shouting at her, Lena would confess all, and then her parents would quarrel and she’d have the evening to herself, maybe go round to Yury’s, or look at the book Father had brought home for her. She could read, she knew she could. She might not recognize all the letters, but when her father asked her, what does this say, she dug a tooth into her tongue, screwed up her eyes and almost always got it right. And Father was a teacher; he’d never lie to her. Soon she’d go to school like him, and then she’d be able to write her name and spell 20out the other children’s names and the different types of animals and all the birds, which you could tell apart by the zigzag edges of their wings and the curve of their beaks. Maybe a few other words, too. She was looking forward to school; at last there’d be an end to the boredom and she wouldn’t have to spend so much time alone, with her mother always away at the chemical plant, sending people running up and down the aisles, and her father stumbling from one classroom to the next. Maybe she’d see more of him when she started school—she might.

Lena bit her lower lip because she felt something warm and wet dribbling into her pants. Her fist tensed. She’d broken a cup, but not on purpose—Mother knew that. Lena had picked it up because it was beautiful—more beautiful than anything in their one-bed flat—and because there was a danger to touching it; nothing must happen to it, ever. It was made of thin, cold china with a curved handle in the shape of Father’s ear—bulgy at the bottom and pointy at the top—and it had a blue lattice pattern broken at intervals by gold double bows that gleamed like fish scales. The rim and base were finely painted, as if the cup had been sewn together with gold thread, and it was clear as day to Lena that no one would ever drink out of this cup. It was an ornament and it stood in the glass cabinet next to a faun figurine that Lena didn’t like to touch because it left dust on her fingers, and because she was afraid of its hairy goat’s legs and cloven hooves. Lena wasn’t sure if such animals really existed. Might she come across one in the woods? Did they all have curved pipes that they played to lure children like her and crooked horns next to their ears for skewering those children when they caught them? Lena tried not to look at the faun when she passed the cabinet. But the cup was different; sometimes she just had to hold it. It was filigree and shimmered like Mum’s jewellery, which was well and truly out of reach because it was 21kept in a box right at the top of the cupboard—and because she shouldn’t be interested in it anyway, Mum said. The cup shattered; she didn’t know how, her hands hadn’t been the least bit slippery. All Lena could remember were the screams—first hers and then her mother’s—and the pain in her ear, and now the wallpaper that she’d been staring at for hours, days, an eternity.

She’d been holding herself so tense to keep from wetting herself that she hadn’t heard her father come in. Now snatches of words drifted down the passage from the kitchen.

‘…the Leningrad china…’

‘…no way to discipline a child…’

‘What do you know about discipline…’

‘I’m a teacher…’

‘And I’m her mother…’

Father was losing. Lena bit her lip even harder and raised her head; she hadn’t noticed it drop on to her chest. She stared straight ahead at the wallpaper, trying to think of her grandmother, Mum’s mum. She would have helped her out of this. She wasn’t as soft and warm as Father, knew how to speak her mind and had a loud, clear voice, just like her daughter. Sometimes, when the two of them were talking, their words sounded like whip cracks. And now Mother was cracking the whip at Father and he was growing quieter and quieter, so that Lena could no longer hear him, though he was just the other side of the wall.

Soon Grandmother would come and fetch her. Summer lay ahead and that meant Sochi and the seaside and the house on the edge of town with its smell of musty wood, and the hazelnut trees whose branches Lena would shake. And once—or maybe more than once—she would climb into one of the trees, and her grandmother would plant her fists on her hips and call up to Lena and shake her out of the branches like a nut. A whole summer 22away from Mum. But not yet—Grandmother wouldn’t come for a while yet. It might be days or even weeks. Lena felt a stinging in her pants.

Father was talking to her gently, his face up close to her ear. She could feel the warmth of him, but she held herself stiff; in spite of her wet pants and wet cheeks she said nothing and pushed his hand off her shoulder. Only when he crouched down beside her and asked if she’d like to go to the new technical museum with him at the weekend, just the two of them, to see the steam boilers and the gas turbines—only then did Lena relax with a sigh. She squinted across at him. His chin had gone stubbly again. When he’d left in the morning, his face had gleamed and smelt of cucumber water; now it was strewn with black dots and reeked of railway dust. His hair clung to his forehead; he smiled and ran his hands first over her eyes, then over his. Beneath the finely wrinkled skin, thick veins ran from his knuckles to his wrists. Lena loved the way they popped up and disappeared again, and most of all she loved the mass of little dark-brown spots that covered the backs of his hands—they were her favourite. On one of his hands they made a pattern like a flock of birds flying all the way down his fingers, and when he took her to the museum with the paintings and pointed at the pictures, she was more interested in his moles than in what was on the walls. She liked to watch them run together or flow apart as his hand moved; they were so alive, so much more absorbing than the serious-faced people and pastel-coloured landscapes. The landscapes looked very far away, but Father’s hands were close, and sometimes Lena reached out to touch them. At other times she was content to watch them swing next to her cheek like pendulums.

The museum with the pictures was, in any case, only ever an excuse to get out of the flat, have a walk, stare up at the sky, escape 23the smell of kvass fermenting in jars on the kitchen windowsill. A technical museum full of machines was a very different proposition. It wasn’t an excuse; it was a proper treat. There might even, her father said, be an old aeroplane, but Lena couldn’t listen a second longer; before he could finish his sentence she ran past him to the bathroom and yanked the door shut behind her.

When at last she was on the toilet, waggling her feet which tingled with relief, she began to imagine shiny screw threads and huge drills, milling machines and saws—things she’d never seen at home in Horlivka but which she knew from Sochi, where there were mountains of sawdust everywhere; all summer she ran in and out between them with Artyom and Lika. Both children had long black hair, but the sawdust made them look almost as fair as Lena. The three of them teetered on the sides of the mounds, shaking themselves like the stray dogs on the estate and squealing when the sawdust flew in their eyes. The woodchips heaped up at the roadside got into everything too: scalps, mouths, socks. In Sochi, Lena was allowed out with her friends on her own, at least on the estate where her grandmother lived—where the hazelnuts grew.

Before Lena went to bed, Grandmother would chase her round the house and try to shake the sawdust out of her. Lena would shriek with delight, pulling off her pants and whirling them round her head, and Grandma would catch her and lift her up in the air, grumbling about the pale-yellow dust on the floor and the wood shavings that Lena left all over the house, but hugging her close as she scolded.

Grandmother’s hands were rough on Lena’s bare skin, because everything in Sochi was rough from the heat—and from the hazelnuts. Lena’s hands started to itch when she stripped the leaves from the ripe brown nuts, ready to throw into one of the huge sacks that were almost as big as her. The jaggedy-edged leaves that covered 24the nuts like funnels weren’t easy to peel off, but she didn’t mind the prickly feeling in her fingertips because she knew that when she was done Grandmother would take her down to the promenade, where gleaming white paths led to cafés with blue-checked parasols and people in fancy clothes. Lena could never work out what they were dressed up for; they drank lemonade and read the papers, occasionally adjusting their belts or straightening their sunhats, taking no notice of the other customers. Some smoked, some stared past the hotel roofs at the sky. Their sunglasses didn’t come off until the evening, and sometimes you would see the frames glinting even in the light of the street lamps. These people seemed never to work, never to have to pick hazelnuts, never to be in a rush to get anywhere; they sat there straight and stiff, or made a show of strolling around dreamily.

Lena laughed at their strange slowness when she passed them on her way to the candyfloss stall or the merry-go-round—more often the candyfloss stall; she wasn’t keen on those painted plastic animals on a turntable. She stretched out her arms for the thin sticks and held them while Grandmother rolled her own trousers halfway up her calves and Lena’s all the way to her knees. Then they stuffed their sandals into Grandmother’s bag, tramped barefoot down the steps to the sand and stood with their feet in the water. Lena lifted every toe in turn and felt the tingly sensation between them, and when the candyfloss was all gone they plunged their sticky fingers into the Black Sea.

Lena always spotted the first of those strangely slow holidaymakers on the train to Sochi, after Grandmother came to fetch her for the summer. The roar of the wheels on the tracks gave Lena pins and needles, so while Grandmother queued for bedlinen from the guard, Lena scrambled up and down between the berths, scuttling over the bare mattresses like an ant and peering out of the 25window to see if she could see any trees yet—or still only factory hulks, their smokestacks stuffed with crooked plumes that looked as if they’d frozen solid. Grandmother had promised Lena a bottle of sugared milk if she didn’t make too much noise, but the vendor hadn’t come down the aisle with his tray yet and Grandmother wasn’t back yet either. Lena heard the chink of tea glasses in the next compartment and the sound of people laughing. She played with the tickets that her grandmother had tucked into the rack, ran her fingers over the luggage net like someone strumming a musical instrument, and stared out at the long strips of colour as they left Horlivka behind them.

Some of the passengers wore carefully pressed three-piece suits and flowing dresses, even on the train. Outside the compartment door, which Grandmother had left open, a woman in an eggshell-coloured suit was leaning out of the lowered window. Lena couldn’t see her face but she could smell the clove scent of her cigarette and imagined wide frog lips to go with it and eyelashes like thorns. When Grandmother came back with a bundle of sheets and pillowcases, the woman turned to make room for her and her lips were like a prune in her face, dry and puckered and dark purple. She’d painted herself, which was something Lena’s mother would never do, but then this woman was going on holiday and Lena’s mother never did that either—certainly, Lena had never known her to. All she knew was that her mother sometimes put in weekends at the chemical plant. Maybe before she was plant manager she’d worn make-up like this woman. Actually, Lena wasn’t really going on holiday either; she was going to Sochi to work, to help Grandmother shake the hazelnut trees. It made her proud.

Twice a week, grandmother and granddaughter waited at a bus stop on the other side of the hazelnut estate, a bus stop that was 26marked not only by a signpost but by a crowd of people—women with children and sacks full of things to sell. Hazelnuts mostly, Lena guessed, or some other produce from their small gardens; all the sacks looked heavy. Lena was five and stood not much higher than the leather wallets the women wore strapped to their belts, so it was her job to wriggle past their hips and grab a seat on the bus before anyone else got on—preferably a window seat, so that Grandmother could hand her their sack of hazelnuts through the open window. It wasn’t easy, pulling it through the frame, but it hadn’t ripped yet. The thought terrified Lena; if the sack did rip, all their work would be for nothing—the picking and gathering, the itchy fingers. The nuts would rain down on to the ground and the bus would drive off without them. There was never room for everyone anyway; judging by the number of passengers on the bus, half those waiting were left behind at the bus stop, and only fifteen people at most got to sit down. The others had to stand between the seats or wait for the next bus, and that meant getting to the market too late for a shady place to pitch their stalls. Their vegetables would wilt and their skin would be roasted.

The faces of the women at the bus stop looked battered by the sun even first thing in the morning. Strands of hair had come loose from their plaits; their thighs smelt of sour cream. Seen from below, the women seemed to grimace as they peered down the road into the dust. Lena always thought she saw the bus coming before any of the others did—how else explain that she was always first on the step when it finally pulled up in front of them? As soon as the sack of nuts had been safely stowed and her grandmother had sat down beside her, she would slide back and forth on her seat, looking forward to the evening when everyone would have screamed themselves hoarse, filled their leather 27wallets and emptied their sacks—when they would roll up their oilcloths, smooth their hair with their damp hands and tame it with a rubber band or a headscarf. By then the whole market was in shade and beginning to cool down; squashed fruit lay between the stalls and a few shrivelled potatoes rolled around in the dust. Grandmother would press a rouble into Lena’s hand and pack up her things. Lena’s very own earnings. A whole coin for every trip to market, a coin stamped with signs and a bearded male profile, a coin that Lena spent on treating Grandmother to dinner. Their tummies rumbling and the empty jute sack dangling, they would head straight from market to the town centre, always to the same canteen on the ground floor of one of those tall buildings that seemed to shoot up into the sky. Lena would put her coin on the counter and ask for a plate of pelmeni, which she would set down on the table in front of Grandmother. It came with cream, but instead of pouring the cream over the mountain of dumplings they drank it straight from the pot, cooling the hot meat in their mouths.

Sometimes the neighbours had a barbecue on the estate to celebrate a birthday or wedding, and the table of grilled and roast meat was so long that all the children from the estate could sit underneath. Grandmother explained to Lena that people here sang before they ate the animals because it made the food holy—the effect was especially powerful if you did it with your eyes closed and your head bowed. Lena didn’t join in the singing, but she looked at the murmuring mouths on the momentarily serious, withdrawn faces and, feeling the desire to do something herself, she kissed the corner of the tablecloth. Her grandmother never took her to church, but she often made the sign of the cross—something that Lena had never seen her mother or anyone else in Horlivka do. Sometimes 28she tried to copy the motions, but she didn’t know which direction to start off in and ended up doing an uncoordinated finger dance, which made Lika and Artyom laugh.

Once, when she went to the mountains with Lika’s parents and Artyom’s mother, she tried to pray properly before eating, putting her hands together and bowing her head. The grown-ups had spread out rugs by the river, uncorked bottles and anchored the legs of the barbecue in the sand. Lena peeped at her friends and moved her lips with them as they said thank you for the food. When the shashlik was all gone, they said thank you again.

Lika and Artyom were a little taller and faster than Lena; they ran up the hill into the woods and thrust sticks into her hands so that she could protect herself against the otters. You had to bash the grass in front of you, Lika said. And if they didn’t come, Artyom said, you could lean on your stick and hike like a real Pioneer.

Whenever Lena spent the summer in Sochi she expected to have to fight off vicious, poisonous animals, to be pulled into dank underground caves by gnomes, like in the books that were read to her at home, or encounter real fauns—big ones with hairy, musty-smelling goats’ legs; maybe with pan pipes, maybe without, but definitely ready to use those curly horns of theirs to skewer small children who had lost their way. She examined the grass carefully for hoofprints the size of grown-up feet and often had a stone handy, so that she could throw it between the faun’s wide-set eyes if she had to. She’d never come across an animal in the wild, not even a fox, but she dared the woodland sprites to come out by standing at dark hedges for longer than necessary, holding her face close to the twigs to see if she could smell something more than leaves and grass. Maybe musty hair. Sometimes, very rarely, she saw fireflies flash over the scrub. She decided they must be the gleaming eyes of much taller beings, 29but, not daring to reach out and touch them, she only stared back warily.

Until she stepped into the museum lobby and saw the turbine of an aeroplane right there in front of her, all she could think of was Artyom and Lika, their black manes and whether they’d grown longer again and whether this might be the summer when she would learn to swim at last—maybe in the mountain river, which she liked even better than the city beach. She’d recently seen a film about a shiny green creature, half-man half-beast, with fins on its legs and a crest on its head—a creature with both lungs and gills. It lived in the bay of a warm country and sometimes came frighteningly close to the shore, destroying fishing nets and sinking boats. Lena preferred clear, shallow water. But when she saw her father’s distorted reflection in the steel engine case it made her sneeze with excitement. She forgot all about Amphibian Man, all about Artyom and Lika. The engines filled the enormous halls of the museum. Lena’s father strode ahead as if he were in a hurry, but she’d never seen such huge propellers before and was determined not to rush; she barely listened when he spoke to her. In each of the vast rooms she circled the displays several times, hiding when her father called her and refusing to hold his hand. She was so mesmerized by the generator in a scale model of part of a power station that even the prospect of ice cream couldn’t lure her away. It was only when Father threatened to leave without her that Lena ran after him, and as soon as they were outside and the magic of the machines began to wear off, she felt suspicious of his offer of ice cream—it was a bad sign when Father promised sweet things before lunch. In fact, he’d been strange all morning, talking all the time, his hands damp with sweat. He only talked like that when something wasn’t right; the words seemed to pour out of him. 30On an ordinary day he could sit at the window for hours on end without speaking, staring out at the mottled white trees across the road, as if something were happening that he couldn’t afford to miss. Now he talked and talked, wiping the spit from the corners of his mouth with the back of his hand, telling Lena something about shoes—that you didn’t wear your outdoor shoes inside the school building, but brought another pair to change into, in a drawstring bag that dangled from your satchel. And that there’d be a uniform for her and she’d have a white pinafore to wear on special days, and a black one for the other days. That she’d be a Pioneer when she was bigger and then a Komsomolet, but not just yet—first she’d be a Little Octobrist. She’d have a red badge in the shape of a star and would be able to help out in the community, watering plants in the classrooms, for example, because that was what Little Octobrists were good at—working for the collective. He warned her that there were rules for the Little Octobrists, the most important being to work hard, love your school and respect your elders. There was a lot more too, she’d soon find out, it would all be great fun. She’d paint and sing and read and do sums with lots of other children—and so this summer would be a bit different, she wouldn’t be going to Sochi. By now they were standing outside the kiosk holding their cones, and Lena had just sucked half a scoop of ice cream into her mouth. She went hot and cold; she forgot to swallow.

‘You’ll have to prepare for school over the summer. I’ll help you,’ said Father, coming to the end of his monologue.

‘And Grandmother?’ Lena whispered. ‘Won’t I ever see her again?’ Her thoughts were all over the place. Hazelnut-trees-Artyom-and-Lika’s-hair-and-gappy-teeth-the-market-the-beach-the-candyfloss-the-silly-slow-people-on-the-promenade-in-Sochi.

‘Grandma will come to Horlivka,’ Father promised. ‘She’ll come and stay with us. She’s found someone to look after her garden 31so she can be with you. She’s looking forward to it. We’ll put up a camp bed for her in the sitting room, she’ll cook lunch for you every day, you’ll see much more of her now.’

‘But the hazelnuts won’t grow without Grandmother!’ Lena waved her arms about; the ice cream fell on her sandals and seeped between her toes. There was so much else she wanted to shout: But Artyom and Lika will learn to swim without me! They’ll see the green creature with gills and lungs rise up from the waves! All we have in Horlivka are fat black cats that cross your path from right to left and bring bad luck!

But all she managed to get out was, ‘Where will I get the money to treat Grandmother to pelmeni?’

‘Pelmeni?’ Her father’s eyebrows shot up as if he were hearing the word for the first time. ‘Money? What money?’

It was no good talking to him. Could you even get pelmeni in Horlivka, or would she now be trapped forever in the stinky kitchen with the kvass on the windowsill, condemned to eating noodles with grated cheese? And what did he mean, Grandma would sleep on a camp bed? There wasn’t an inch of space in the sitting room. When you pulled out the sofa bed that Lena slept on it reached all the way to the legs of the dining table, leaving only a narrow passage on the other side along the front of the glass-doored cabinet with the faun figurine and the Leningrad porcelain. Maybe Grandmother would sleep on the cupboard next to the cabinet? But that was where the fancy vases were kept, and some boxes or other that Lena sensed rather than saw. In Sochi Lena had a room of her own, and you could play hide-and-seek in the musty cupboards. Here in Horlivka the drawers burst like overripe fruit when you so much as stretched out your fingers towards the handles, and there were suitcases in the bottom of her parents’ wardrobe that she wasn’t allowed to touch. Grandmother would have to sleep on 32top of Lena, squashing her with her wiry body; she would sit and doze in the kitchen with her head resting on the table; she would cower in the hall on the old chest hung with dusty rugs. Sensing that the whole business of school was more serious than she had realized, Lena decided not to cry. If her father had made up his mind to ruin her summer and the rest of her life, it was best to be on her guard. She was surrounded by traitors.

Father took a handkerchief from his jacket pocket, wiped the sticky mess from between her toes and asked if she’d like another ice cream, but Lena felt numb and also insulted that he was pretending everything was the same as ever. Why was the world still turning? Why were all these people walking past with their usual cheerful faces? Didn’t they realize that nothing would ever be the same again? Didn’t they realize how bad things were going to be?

In all the photos taken at the first-day-of-school ceremony Lena looked grim. Hundreds of girls and boys stood hand in hand in rows on the school steps, smiling at their parents, careful not to let go of each other’s hands and wave. Their palms were cold and slippery, and Lena tried not to look left or right. Her white pinafore had been tied too tightly round her bum and hips, but she hadn’t complained. She screwed up her eyes and concentrated on the slight itch where the ties chafed her flesh. Her hair was so short that she could no longer braid it into proper plaits—Grandma and Mother had argued over whether or not to cut it and, as so often, Grandma had won. Since coming to live with them, Grandmother had spent a lot of time sitting on the camp bed they’d bought for her, scratching the backs of her hands with her bitten fingernails till the skin was raw and then running the sore spots over her face like a cat washing itself. It was a habit Lena had never observed in her in Sochi.

33Lena hadn’t known her grandfather, and the few times she’d asked about him she’d got nothing out of the grown-ups; they’d only changed the subject or said things that made no sense. There had always been Grandmother without Grandfather—that was normal—but now, moving around the cramped flat in Horlivka, Grandmother seemed somehow incomplete. As if she were missing something, or someone. As if she were looking for something she’d had in her hands just a moment before. Another change was that there was no pleasing her any more. She was forever complaining that it was too stuffy in the flat, but if you opened the window it was too loud. She told Lena not to galumph around and disturb the neighbours, but if Lena crept past her on tiptoes she was told to ‘walk like a normal person’. Every evening Grandmother stood at the stove, holding angry conversations with herself under her breath and running the wooden spoon round and round the edge of the saucepan. The pervasive smell of food and the angry whispers made the flat seem even smaller; the ceiling felt suddenly lower, and Lena would wake in the night and—secretly, so that no one would notice—she would peer at it to see if it had come closer in the dark. It was because of the smells and the anger, Lena decided, that her mother didn’t come home from work until everyone was in bed. But even then there were fights.

Often all it took was a dry You’re back early, or an Oh, so you live here too? Lena couldn’t make out what the arguments were about—all she knew was that the voices started off soft and husky, then grew suddenly louder, as if a door had been flung open on a singing choir. It seemed to her further proof that school brought no good. She hadn’t taken part in the fierce debate about her haircut; no one had consulted her. Mother and Grandmother had bickered over her head about what was best for the child while thick clumps of hair fell on to her slippers. The newspaper spread out under 34her chair was crumpled and yellow; it covered the whole of the kitchen floor, making it look like a lightly toasted crust of bread that would tickle your feet if you walked over it barefoot.

Before setting off for school they had pressed a bunch of flowers into Lena’s hand, pulled her white socks up to her knees and told her to smile at the camera. She remained impassive, obediently took Grandmother’s hand when Father had put the camera away again, and climbed without a word on to the bus that she would now be catching every day.

Tap-tap-tap-tap, her wide-mouthed shoes said as she approached the school building. Lena counted her steps, trying to slow down. She glanced up only once, as they passed the man with a goatee. The man’s name, she knew, was Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, a name you spoke with pride, breathed in awe. Lena tried to do just that in her very first lesson, when she was asked who the school was named after. She rose, positioned herself at the side of her desk and tried to breathe the name Vladimir Ilyich Lenin with the requisite pride and awe. The other children giggled. Then there was silence. The teacher asked again—this time a blond girl in the front row, who jumped up like a mattress spring, positioned herself, like Lena, at the side of her desk and solemnly declared, ‘Yuri Gagarin!’. Then she turned her crescent-moon profile to the class, so that everyone could see at least half of her smug smile. The teacher nodded and asked both girls to sit down. Lena felt numb with shame and decided that in the next ten years she was to spend at this school she would never ever open her mouth again.

There was no avoiding the Little Octobrists’ song; it was a fixture of the primary-school repertoire:35

Little Octobrists near and far,

Active boys and girls we are!

Little Octobrist, listen here,

Soon you’ll be a Pioneer!

But however often Lena sang it, Pioneer remained for her the name of the camera that her parents kept on top of the cupboard and had so far taken down only once, on her first day of school. It wasn’t until the beginning of Year Three that Lena fully grasped the significance of becoming a Pioneer, when her mother announced that she would now be spending every summer at a camp, running around outside and learning to be part of a community, a collective. While she was away, Grandmother would return to Sochi to pick the hazelnuts and make sure everything was in order—she’d be back in time for the autumn term. The neighbour who was looking after her garden and living off the hazelnut crop was moving to the next village to live with her children. She had back trouble and all manner of aches and pains, and Grandmother needed to find someone to replace her. Besides, she missed her house and the garden.

Lena’s mother sighed. ‘If it was up to Mum, she’d stay there. She hates it here, hates living with me, hates our flat. We must be grateful that it doesn’t stop her scrubbing the floors and keeping us in chicken soup. I hope you’ll thank her when you’re a big girl—she’ll listen to you. My words go in one ear and out the other. She grumbles that she wants to go to church in Sochi again. I tell her she can go to church here. Then she sits down in the corner and sulks, as if she’s been hard done by.’

Two black manes danced in front of Lena’s eyes, shaking themselves like dogs. Mouths with gappy milk teeth appeared before her; thin arms, bronzed by the sun and the dust, flew through the 36air. Artyom and Lika rolled around in the sawdust while she stood next to them looking on—much older, ridiculously tall, wretchedly clean. She dug her fingernails into the palms of her hands and asked as calmly as she could why she couldn’t go to Sochi with Grandmother, but her mother flew off the handle before she’d even finished speaking. ‘You’ve no idea what it cost me to get you into that camp! It’s usually only Party cadres’ children who get a place at the Eaglet!’

No wonder, then, that she hated the ceremony where she was presented with her Pioneer’s neckerchief. When the class was asked who had excelled in their duties and lessons and should be the first to receive the neckerchief, she pretended not to hear her name and didn’t go to the front until the boy next to her, Vassili, gave her a push. Vassili was one of the last to be honoured; he stared vacuously and tried to smile, and Lena smiled back because he looked so funny with the red at his neck and the red of his hair—almost pretty.

When the school committee divided the Pioneers into work groups, she was pleased that she and Vassili were put in joint charge of waste-paper collection. She didn’t like the smell that came from his shirt collar or the dandruff on his shoulders, but they’d been together since starting school and she was used to him. She’d often helped him with his homework, and once, when he’d come out of the school committee’s office with a hanging head and yellow goo in his eyes, she had put her hand on his. He’d been reprimanded for poor marks. ‘Lenin,’ they had said, ‘urged us to different conduct!’

Collecting waste paper was a serious business; their teacher kept an eagle eye on the amounts they turned in. Lena’s father had smiled when she mimicked his fierce-faced colleague: the way she straightened her glasses, pursed her lips, stuck out her chin and 37instructed the Pioneers to be conscientious—the state, she had said, needed recyclable material. Lena hadn’t quite understood his response: ‘Every schoolchild in the Soviet Union owes the state fifteen kilos of waste paper a year and at least two schoolmates who haven’t made the grade!’ He laughed at his own words, as if something had stuck in his throat, and Lena’s mother joined in. Only Grandmother shook her head and turned back to the steaming pan on the stove.

Joke or no, Lena and Vassili did the rounds of the entranceways, snapping up every scrap of paper they could find, ringing at people’s doors for old newspapers and magazines, assuring them that their donations would help save the forests of the beloved homeland. The two children spurred each other on, tried to outdo each other.

It gave Lena a great deal more pleasure than the monthly shop with her father, for which he would wake her early in the morning, even earlier than on a school day. If it was cold they wore several jumpers on top of each other and a headscarf was tied around Lena’s woolly hat, so that Grandmother’s voice faded to a distant hum. Her father moved awkwardly in the dark streets. It seemed to Lena she could feel the crunch of snow all the way to her jaws, and the cold got into her felt boots in spite of her rubber galoshes. She walked close behind her father so as not to lose sight of him in the dark. The orange cones of the street lamps cast only small circles on the asphalt; they gave off little light and no warmth. Lena and her father tramped through them, their eyes on the ground to keep from slipping. Father rammed his feet into the snow as if he had thorns on his soles; this slowed him down and Lena kept walking into him.

Eventually, the sour smell of sweat and fresh meat made her look up. Her father got into one of the queues outside the grocer’s shop and she joined the other. He gave her a wink; after that they 38pretended not to know each other. Sometimes they both got the ration of pork belly or knuckle they were entitled to; sometimes only Lena did. If neither of them had any luck and the shop woman folded her arms in front of the thronging crowd and let the empty fridges speak for themselves, they would take a packed bus to another shop where her father would enter into a whispered exchange with the shopkeeper—a woman who kneaded her big hands under her yellow floral apron, making a sound like sifting sand. Afterwards, Lena and her father would carry home the meat, salami and butter, and as soon as Lena had taken off her galoshes and felt boots she would fling herself on to the bed, exhausted by the cold and the strain. She dreamt of the warmer months to come—it didn’t have to be Sochi, just as long as things got better again; even if her toes thawed it would be something. Maybe it wouldn’t be the end of the world if she went to the Pioneer camp in June—at least she wouldn’t have to queue for food any more. There would be meals served three times a day and it would be summer at last—warm enough to go in the water.

Lena decided to look forward to it, but when June came she got cramps in her belly.

‘There are six beds in the compartment—you’re in number thirty-seven. The seats are numbered clockwise. Can you show me which way the hands of the clock go?’

Lena drew a semicircle in the air with her fingers, then moved her hands back to her tense, swollen belly. It had been making gurgling noises ever since Grandmother had started folding and packing Lena’s shirts and shorts the day before, reminding her over and over that she mustn’t forget to change her socks every day. Lena had smelt her buttery breath and pondered the fact that no one she knew would be there. Not on the way there and 39not at the holiday camp either. The camp was hours from home; the Pioneers had to take an overnight train and then catch a bus into the forest—the Pioneer leaders would make sure they got on and off at the right stations. For six whole weeks Lena wouldn’t be able to call out to anyone she knew. Her father, as usual, had nothing to say to this. Sometimes he sat on the stool and sometimes on the chair next to the stool, and the rest of the time he wandered aimlessly around the flat. Lena raised her head every time he brushed past her, but he paid no attention either to her or to the half-packed suitcase on the floor, an open mouth silently screaming, AAAAAGHHHH!

He and her mother did, however, see her on to the train the next day—though they spent most of the time in tense silence. The Pioneer leaders interspersed their guttural orders with whistle blasts as they directed the hordes of children to their carriages and compartments. ‘Luggage under the seats! If you’re on a top bunk use the overhead shelves, please! No pushing! No jostling! I said be careful! Hands off the windows!’ The sleeping cars stretched endlessly along the tracks like a string of sausages. Lena stared at the ground until she was hoisted over the steps into the carriage, and once on the train she didn’t go to the window to wave goodbye to her parents on the platform. The carriage reeked of old galoshes and the compartment was nothing like the berths where she and her grandmother had slept on the way to Sochi. No chance of sugared milk here, and no one to lay a hand on her ear to comfort her, no one to hug her tight. Her belly yowled and cramped.

The other five beds were not yet occupied and Lena hoped desperately that it would stay that way. Maybe she could go to sleep and not wake until the six weeks were past. She’d get off the train, walk home, hide under her grandmother’s housedress and it would all be over. But the compartment was filling quickly; five 40pert little bums pushed past her face, and five children chattered away as if they’d known each other forever. Lena’s head began to buzz, and by the time they changed on to the waiting buses the next day the buzz had become a rattle. She didn’t want to make friends, didn’t speak to anyone for the entire journey and was glad when the buses spat out their chewed-up freight at the foot of a hill.

The group leader chivvied the Pioneers up the hill, luggage and all, lined them up in rows and began her speech. Only those with top marks and distinction, she said, had the honour of spending precious summer weeks here at the Eaglet. This rather contradicted Lena’s mother’s claim that it was her good connections and not Lena’s success at school that had got her into this elite camp, but it did explain why Vassili wasn’t here. Lena stared through the rings of the blue metal gateway that led to the buildings and campground; it looked like a forgotten construction that should have been taken down years ago—a climbing frame, perhaps, left over from an obsolete playground. The woods came right to the edge of the camp. You couldn’t see whether the fence ran all the way round the site; its warped mesh vanished into the dappled green of trees and juniper bushes. Lena fancied that somewhere in the distance she could hear the splash of a lake—maybe this summer she would learn to swim at last. Maybe shiny-scaled amphibian men with raised crests would come out of the lake and pull the children into the water.

Heroes Avenue, a narrow cement path leading from the archway to the holiday camp, was lined with the busts of young men. Most had short-cropped hair and some had peaked caps; only a few wore Pioneers’ neckerchiefs of stone. They were set on concrete pedestals as tall as the children, who had to crane their necks to see 41them. The group leader patted her bun, straightened her mustard-coloured dress, which looked like trampled leaves after the long journey, and pointed out one or other of the statues—did anyone know what this young person was called—or this one? Dozens of pairs of eyes turned and stared. The main attraction was a boy with a high forehead and a square hairline far back on his head. He wore a boat-like forage cap perched at an angle and looked very, very serious—almost angry. His neckerchief was knotted tightly over the top button of his shirt, and if the statue had been more than a bust Lena was sure he’d be wearing a leather jacket. She’d seen this wide-eyed, straight-browed face somewhere before, but she couldn’t think where and made no effort to remember his name. The group leader had, in any case, no patience with children who shouted out answers, and took it upon herself to explain that Pavel Morozov was a Pioneer hero who had defied the kulaks and paid for it with his life.

‘Who knows what kulaks are?’

‘Enemies!’

‘That’s right. But why?’

‘Because they betrayed us.’

‘Yes, and how did they betray us?’

Lena knew that the kulaks had been landowning peasants and she knew that ownership was forbidden, but this was the first she’d heard of children reporting their own parents to the kolkhozes for hoarding corn or livestock. Pavlik Morozov, it seemed, had done just that: he’d reported his father to the village chief for hoarding stocks of grain, and for this his grandfather had stabbed him to death along with his little brother when they were in the woods, picking berries. While the other Pioneers raced on down the avenue, Lena lingered a moment longer at Pavlik’s cut-off bust. She stared into his lidless eyes and sneezed.

42That night, Pavlik’s high forehead hovered over the end of Lena’s mattress and sneezed whenever she glanced up at him, a strange, open-eyed sneeze—hachoo. Lena got the hiccups she was so scared; her belly started to gurgle and cramp again. She could hear the girls in the next beds talking in low voices and tried to make out what they were saying, hoping that their murmuring would soothe her and make her forget that knife flashing in the cranberry bushes. But they didn’t seem able to get Pavlik out of their heads either. They whispered that as well as being stabbed to death, he and his brother had been chopped up with big knives and eaten, because that was what the kulaks did—they killed their children and gobbled them up. They had an insatiable hunger and refused to share with the community, and so trucks had come and taken them away, and when their children were put into homes they turned out to be every bit as greedy as their parents, tearing the flesh from each other’s bones and eating it, leaving their little brothers and sisters out in the snow to freeze to death, and then boiling up the corpses. Pavlik Morozov had been a rare exception.

Lena stayed awake all night, watching the bodies of the other Pioneers rise and fall under their blankets; in the dark dormitory it looked as if someone had dumped grey earth over their curled-up forms. The big white bedsteads had legs on castors and saggy-bellied mattresses as soft as bread. They stood far apart from one another, each shadow distinct. Some girls snuffled in their sleep; the girl next to Lena chirped like a cricket all night long.

Lena ran her hands over her upper arms to calm herself, up and down, up and down, as if trying to smooth her gooseflesh. When the reveille sounded she leapt out of bed. She was the first in the washroom and the first out on the parade ground, where she stood at a neatly swept fire pit and waited until the others joined her and the bugle at her ear blasted every last thought from her mind. The 43Pioneer who had blown such a fierce reveille wore a loose-fitting shirt tucked clumsily into his shorts; Lena thought he looked like a half-inflated balloon letting out little puffs of air. Behind him, a huge board headed daily routine read:

1. Get up 8 a.m.

2. Gymnastics 8–8.15 a.m.

3. Tidy dorms and lavatories 8.15–8.45 a.m.

4. Roll call and hoisting of flag 8.45–9 a.m.

5. Breakfast 9–9.30 a.m.

6. Free time 9.30–9.45 a.m.

7. Clean campsite 9.45–10 a.m.

The next items were obscured by the bright red flag with gold fringe that hung from the bugle, but at number 10 the list resumed and Lena could read: Free time, and then, 11. Lunch, 12. Afternoon nap, 13. Tea, 14. Group classes, 15. Free time, 16. Supper, 17. Communal activities, 18. Evening roll call and lowering of flag, 19. Evening toilet, 20. Bed.