Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Paraclete Press

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

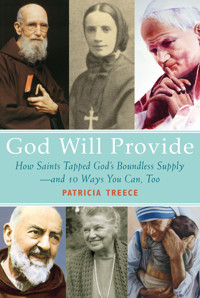

A specialist in human goodness and recent saints, Patricia Treece offers the fruits of years of research on how God meets the material needs, in varying ways, of his people. Mother Teresa of Calcutta, for instance, refused to let anyone raise money in her name, insisting if God wanted something done through her, he'd send the money. Other friends of God did seek donations and got them in amazing ways. Most intriguing of all, Treece found people living quietly anonymous lives secure in God's providence. From them she has learned to live that way, too. In this lively book she offers copious examples of ten universal principles to live by so you can join those who know, in good times or bad, God will provide.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 270

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

God Will Provide

How God’s Bounty Opened to Saints—and 9 Ways It Can Open for You, Too

PATRICIA TREECE

God Will Provide: How God’s Bounty Opened to Saints—and 9 Ways It Can Open for You, Too

2011 First printing

Copyright © 2011 by Patricia Treece

ISBN 978-1-61261-045-0

Scripture references are taken from the Lectionary for Mass for Use in the Dioceses of the United States of America, second typical edition copyright 2001, 1998, 1997, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC. Used with permission. All rights reserved. No portion of this text may be reproduced without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

Cover photo of Fr. Solanus Casey taken by Br. Leo Wollenweber, OFM Cap. Used with permission of the Fr. Solanus Guild, 1780 Mt. Elliott, Detroit MI 48207. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Treece, Patricia.

God will provide : how God’s bounty opened to saints and 9 ways it can open for you, too / Patricia Treece.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-61261-045-0 (pbk.)

1. Spiritual life—Catholic Church. 2. Providence and government of God—Christianity. 3. Christian saints. I. Title. BX2350.3.T74 2011

248.4′82—dc23

2011036835

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete PressBrewster, Massachusettswww.paracletepress.com

Printed in the United States of America

To all who need and wantDivine Providencein their livesandto God’s friend and mineAlice Williamswhose prayers have obtainedfrom Divine Providence every kind of graceand blessing for me, my family,and countless others.

CONTENTS

A NOTE TO MY READERS

PROLOGUE: God Will Provide

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTEROne

In Life’s Dance, Why Not Let God—Who Knows All the Steps—Lead?

CHAPTERTwo

Other Things It’s Smart to Give to God

CHAPTERThree

O Ye of Little Faith—in Other Words Most of Us

CHAPTERFour

Grow Your Faith

CHAPTERFive

Run! Avoid Faith-Killers

CHAPTERSix

Cultivate Gratitude

CHAPTERSeven

Retool Your Mind

CHAPTEREight

Practice Belief in God’s Providence—Even Fake It When Necessary

CHAPTERNine

Do Your Part: “Let’s Go Dutch” and Other Opportunities to Practice Financial Discipline

CHAPTERTen

Don’t Block the Flow

CHAPTEREleven

Pass It On!

A REVIEW LIST of Nine Ways to PositionYourself to Receive Divine Providence

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SOURCES ON THE SAINTS

INDEX OF NAMES

A NOTE TO MY READERS

Don’t be afraid to read this if you’re not Catholic. The principles are universal and will work for anyone willing to give them a try. If the word saint seems strange, call them “God’s friends.” And yes, some of God’s non-Catholic friends turn up here, too.

Because there are some stupendous true stories in these pages, let me assure you: anything involving a saint is taken from the authentic sources as verified by the individual’s order, shrine, or my years of research into the individual’s life, writings, letters, and the testimonies, often under oath, by those who knew them. The smaller number involving non-saints happened to people of the highest integrity I know personally (except for never having the honor of meeting the late founder of Habitat for Humanity, Millard Fuller) or are events I was involved in myself.

As an example of my sources, the prologue you are about to read was written from the testimony of an eyewitness, a saint’s coworker and fellow Capuchin Franciscan. The Capuchin order supplied a copy of the account for my work. However, since copious footnotes scare away some readers, it was decided to put only some sources in footnotes and give others in a section entitled “Sources on the Saints,” found at the back of the book. I hope this solution will promote readability for all, while without too much trouble, providing for you who need surety that I have not made up even one of this book’s amazing events!

PROLOGUE

God Will Provide

The Depths of the GreatWorldwide Depression of the 1930sSt. Bonaventure FriaryDetroit, Michigan

“Father Solanus, Father Solanus!” Father Herman Buss rushes into the porter’s office, where his fellow Capuchin1 has been giving himself totally, as usual, to someone in need. “Sorry,” Father Herman says as he brushes past a radiant-faced woman heading out of the office door. “There’s nothing to offer the men. Not even a scrap of bread, and we’ve got two or three hundred waiting for the door to open.”

The porter of St. Bonaventure’s Friary on Mount Elliott Avenue, Father Solanus, turns serene blue eyes to Father Herman. He nods in understanding. He doesn’t say, “Why tell me?” After God himself, the poor and the sick are Solanus’ greatest love.

As for the sick, whether in Solanus’ three posts in New York, Indiana, or here in Detroit, Michigan, there have been so many “impossible cures” through the smiling, stick-thin Capuchin’s prayers that he has been charged with keeping a log of visitors’ prayer requests and the results. He does so gladly, knowing it is God, not he, who heals.

The poor and hungry always turn up at monasteries. Solanus has fed many a man in the friary kitchen—sometimes cheerfully setting his own simple dinner before his unknowing guest. But feeding individually will no longer do. The Depression has brought the desperately hungry out in unprecedented numbers. The Capuchins have opened a soup kitchen—although the standard meal is not soup but a meaty stick-to-your-ribs stew meant to sustain someone eating only once a day. The kitchen is down the block from the friary in a building devoted to Third Order (that is, lay, or non-ordained) Franciscans. Although no one voices this, Father Herman has no doubt that Solanus is the spiritual force behind the kitchen, that in an ongoing miracle is feeding as many as three thousand a day.

Whenever Solanus’ job of porter lets him get away, he helps materially as well. This may take the form of a trip out to a farm to pick fruit a farmer offers or to help load free vegetables for those hearty stews. Wisconsin farm-bred, his brown habit’s hood slung back, Solanus finds the same stores of energy for throwing sacks of potatoes onto a volunteer driver’s truck that he once displayed as part of the Casey brothers’ baseball team. In town he pitches the needs of the hungry to butchers, bakers, and anyone with significant food to spare.

But the day has come at last.

In spite of all Father Solanus has done, in spite of all Father Herman, assigned there full time, has done, in spite of all the volunteer lay Franciscans who cook, serve, and themselves donate, have done, the kitchen is out of food.

Father Solanus walks back with anxious Father Herman, who will never forget and later report in writing2 what happens next. Solanus goes out to the men. He doesn’t tell them he is sorry there is nothing to feed them today. He tells them truthfully, “There is no food.” Then, even as some—among them men who have not eaten for several days—prepare with despairing faces to turn back toward the street, he says authoritatively in his low voice permanently scarred by childhood diphtheria, “Wait. Just wait. God will provide.”

Lined up are men of every stripe—the gamut of Protestants, a sprinkling of Jews, devout Catholics and Catholics in name only, and people who have nothing to do with any kind of religion. Without insistence, Solanus—whose God-given miracles go out as readily to any who ask as to his fellow Catholics—invites them to join him in prayer. Many follow along as he says the Our Father with its petition “Give us this day our daily bread.”

Barely has the last word left his lips when a man dressed in a bakery uniform seemingly appears out of nowhere, making his way across the line of men with a huge basket of bread. One basket isn’t enough for two hundred to three hundred men but no matter: as he passes into the kitchen, his voice floats back saying he’s brought a truckload of foodstuffs.

Relieved and overjoyed, some men start to cry, tears glistening on whisker-stubbled cheeks.

Solanus, who sees God do astounding things day after day, says, “See, God provides. Nobody will starve so long as you put your confidence in God, in divine providence.”

1 One of three major and many smaller religious Orders that follow Christ via St. Francis of Assisi’s spirituality.

2 Testimony of Father Herman Buss in Written Reports Concerning Fr. Solanus Casey, OFM., Cap. June 4, 1984.

INTRODUCTION

Most of Solanus’ listeners on that day of the Great Depression were too sunk in their own sadness or too hungry to draw out from his words any practical personal application. Most who wept did so not because they had been suddenly enlightened by a great truth that would remake their lives but because—amazingly, unexpectedly rescued—they were going to eat after all. Those without faith in supernatural realities may have chortled, “My lucky day,” or the well-educated murmured, “A wonderful coincidence.” Those with faith, most likely, would have been inclined to ascribe the “miracle” to the prayers of Solanus, obviously, from what had happened, a “holy person” with whom they had nothing in common.

What Solanus longed for others to grasp is the subject of this book: that if you’re willing to open yourself to it, this kind of answer to prayer—demonstrated by saints of our time like Venerable3 Solanus Casey—is available to everyone, including you.

This book, that is written for you with love from God, God’s saints, and the author, braids encouraging, authenticated incidents of how God met the financial/material needs of holy people from the so-called modern era (some canonized, some beatified, some on their way, and some just saintly folks whose holiness will never be recognized beyond a limited circle) with ways for you to position yourself to receive this kind of help. Called divine providence, it is the caring, providing, needs-fulfilling aspect of God. Each chapter covers a particular aspect of living in divine providence and suggestions, with examples from the saints, for reshaping your attitudes and actions to that end.

Need you become a saint? Let’s put it this way: the surest way to receive a truckload of foodstuffs when you need it is to be holy. But I know a fairly large number of people who live by the guidelines in this book as best they can—Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and unchurched—who are not saints but whose lives demonstrate that these principles work. The book will report some of their prayer answers, too.

Living by these principles will lead you unavoidably toward becoming a better and better person. And since that’s how one moves toward maximum human fulfillment and a joyous life after death, you could say that what you have here are guidelines for dealing not only with your material/financial needs but with your emotional and spiritual ones, too. In financial terms, you get “two for the price of one”!

3 Venerable, often shortened before a name to Ven. (similiar to shortening Saint to St. and Blessed to Bl.), is the title for those whose heroic virtue has been formally recognized and is an early state of the process toward official sainthood in the Catholic Church. Before heroic virtue is official, candidates are titled Servant of God.

CHAPTEROne

In Life’s Dance, Why Not LetGod—Who Knows All theSteps—Lead?

NOBODY WOULD STARVE, SOLANUS ASSURED THE HUNGRY, SO long as they had confidence in God.

God wants to provide for everyone. Divine mercies fall like life-giving rain on both the just and the unjust. But if you put up an umbrella of self-sufficiency, anger, or disbelief, God respects your freedom to remain parched and dry.

Still, if you’re tired of going it alone and want to live in God’s providence, you can turn over your life to God’s leadership. If you take a bunch of kids on a picnic, they expect you to provide everything. A life that is turned over to God—even though you’ll need to do all the things common sense dictates to help yourself the way the kid has to get ready to go and feed himself—invites the same expectancy.

It’s simple: just tell God you will to let him lead in life’s dance (or captain your ship or guide you on your life journey—whatever metaphor you resonate to). If you turn around and find you’re trying to run the show on your own again, don’t be surprised. Laugh at yourself, if you can, and start over.

If the idea of God’s leadership makes you have to pray, “I trust you. Help me trust you more,” that’s great, because it’s truthful. Being truthful is absolutely essential in forming a real relationship with God, and it’s true that trust has to grow in most people.

What if it’s worse than that? What if your need for control is so great that giving your life to God is terrifying? If that’s true for you, and you are in serious financial or other difficulties, try thinking of it as allowing a firefighter to lead you out of a building collapsing in flames. Or if things aren’t that bad, picture yourself in any kind of a house being invited into a much finer, more spacious one. And keep pondering this: God does not want your surrender to enslave you. He wants your surrender to his loving leadership so he can free you from all those ideas, habits, and situations that imprison you—including your terror of losing control. He has no mold either: He loves variety and rejoices in your uniqueness, loving you with a completely unselfish desire for you to become all you can be. Your fulfilled life gives God glory and joy.

WHO NEEDS TO SURRENDER?

On the other hand, you may think, as a believer, you have no need to surrender. The life of Bl. John XXIII (d. 1963) can shed light on that. The impoverished, peasant sharecropper’s son could never remember when he didn’t want to be a priest. That his dream meshed with God’s desire for his life was obvious when God provided the means through scholarships and gifts.

Still John, like everyone, eventually faced an important choice between “my way and thy way.” In 1925, long before e-mail, cheap long distance, and other means existed to keep in close touch from afar, jealous people got the popular churchman exiled to remote non-Catholic Bulgaria. The transfer meant burying his gifts, loneliness, and isolation, hostility by the host people who feared and hated Catholics, and leaving behind his beloved family, hardest of all the two unmarried sisters who had lived with him. Named archbishop, which would mean nothing in Bulgaria, John took the motto “Obedience and Peace.” He chose surrender to a plan he couldn’t understand and that made him suffer, ignoring friends who urged repeatedly that he complain. Bishop John spent the next roughly twenty years in Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece among wily monarchists and their determined Communist assassins, anti-religion republicans, and Fascist or Nazi invaders, and the guerilla movements opposing them. Religiously he worked with unfriendly Orthodox and wary Muslims, plus the imperiled Jews he helped rescue in World War II (he had already worked with Protestants and other non-Catholics as a military chaplain during World War I). Then he served nine years in secularized post–WWII Paris, among atheists, Socialists, and hardheads on both left and right. In a world suddenly shrinking due to new technologies, these experiences formed a man uniquely qualified for the papacy because of his wide understanding of other peoples, cultures, philosophies, and faiths. As for John’s personal life, his experiences of God’s care led him to dub himself “the son of providence.” His wholehearted surrender also made him a saint, as well as one of the happiest, interiorly freest men in history.

Did you grow up with a dream? Often your dream is your dream for a good reason: it’s God’s desire for you too. Sometimes, on the other hand, God has a bigger, better dream that will bring you a richer life. Another saint exemplifies that. This is her story:

Imagine that you are little Francesca Cabrini, the youngest of a very big Italian family. You have your own unique dream. When you grow up, you are going to be a missionary to China. One day you are enjoying some sweets at a family gathering. To tease you, someone says, “Oh, Francesca, missionary sisters don’t eat sweets.” You swallow the mouthful with two feelings—a bit of sadness and a lot of determination. If sweets are going to stand between you and your dream, you don’t want them. The teaser was only kidding. But you don’t know that. You never take another sweet—not just that day, but ever.

Finally you grow up and after many setbacks—foremost that no missionary order will accept you because you are too delicate, too frail—you have become a sister. A priest, seeing that you would not give up your dream and no one would take you, directed you to found your own order. You have named it the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart, because you are crazy about Jesus. You are going to take him to China so the Chinese can bask in his tender love too. Other young women have joined you, and you are ready to go.

And today, unbelievably, you have an audience with the pope himself! But what is this? Can your ears be working? No. No. No. The pope is saying, “Don’t go to China. You are needed in New York and Chicago, Seattle and Los Angeles, in the Colorado mining camps and other places where your fellow Italians are dying without a word of comfort in their own tongue, where they are leaving orphans with no one to care for these children but well-meaning people who can’t speak to them in their language and have no special love for—maybe even look down on—our Italian culture and religion. Take Jesus to America. Forget China.”

If you cut your beautiful dream into little pieces and throw it away, because you see that what is wanted by the Lord is something other than what you have worked and dreamed toward your entire life, that is surrender at the heroic level.

Such a spiritual heroism led American naturalized citizen and patroness of immigrants Mother Francesca Cabrini to sanctity as a canonized saint and took thousands of people with her to holy lives and Heaven: North Americans, South and Central Americans, Europeans, and perhaps—in the divine economy, where things renounced for God can be offered up as prayer for others—a lot of Chinese too.

ACCEPTING A TWIST ON YOUR DREAM

Another form someone’s call to surrender can take is accepting a twist on your dream. In the case of Father Solanus Casey, joy followed accepting a new, humiliating spin on being a priest:

Young Casey’s love—after a teenage relationship didn’t work out—slowly turned to God, not in bitter disappointment but in awe, wonder, and joy. Having learned to be comfortable with many kinds of people from such jobs as streetcar conductor and prison guard, he heard God’s call to use his great ability to love others in the priesthood. Irish-American, he was permitted by God to have classes in Latin or German. Although he was smart enough, he had no flair for languages, and tackling complex subjects, such as canon law, dogma, and Scripture, in a foreign language proved extremely tough. In the end his unimpressive scholarly attainments led the Capuchins—who recognized his spiritual and interpersonal gifts—to offer ordination but only as a “simplex priest.” This rare type of priesthood denoted that a man didn’t “know enough” to preach on dogma or to hear confessions that sometimes involve complicated moral situations.

Hurt, maybe even indignant, Solanus swallowed his pride and surrendered to God’s twist on the dream plan. Because of these limitations, he couldn’t function fully as a priest, so he was given the lowly job of porter, the man who answers the monastery door. With this second surrender, Solanus was positioned to be God’s instrument for thousands of physical, psycho-spiritual, and moral cures over his lifetime, as seekers of prayer, consolation, healing, financial assistance, food, or other help rang the bell. His life became fuller and fuller in joy as he gave himself away in service to humanity, living out God’s plan for his priesthood. Many times he exulted, “All God’s designs are wonderful for those who have faith.”

Surrender—while it boils down to willingness to trust God’s leadership—has many facets. Hopefully, you’ll soon see more and more the wisdom of surrendering everything as much as you can. For example, here and in the next chapter are six additional, specific aspects of surrender with holy examples for each. The examples are plucked—take me literally here—from thousands of possibilities, since every saint has surrendered to God, either early or late. From them you can preview that by letting him lead, he will be able to do incredible things in your life, awesomely enlarging its possibilities and meeting your needs.

1. Surrendering to God means giving your goodness to God.

When you give your goodness to God, you give him your dreams, your talents, your special gifts, including those virtues that come easily to you or that you have acquired with hard work. There are countless gifts—yours might be engineering things or nurturing others, building houses or one of the arts, cooking, working with money or organizing things, or more subtle gifts such as the ability to see another’s point of view that makes a mediator or the gift of prayer. Your virtues might include a cheery disposition, moral or physical courage, generosity, warm hospitality, or financial integrity.

One way of trying to let God lead when making decisions about developing and using your goodness is Ignatian discernment originating in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola. Ignatian discernment is an effort to recognize what’s going on in one’s soul based on feelings of consolation (peace, joy, contentment) and desolation (restlessness, anxiety, troubled unease). If considering a possible decision brings not momentary exuberance but ongoing feelings of peace and joy, while there is no absolute guarantee, it probably indicates God’s design. Consulting trusted mature Christians who know you, such as your confessor or friends who truly want what is best for you, can be another way to find the path God has laid out for your maximum fulfillment. One way or another God will lead if that is your desire. Take two examples:

A man today titled Bl. Louis Martin dreamed of using his physical prowess, courage, and love of God as a monk in an Order that saved travelers in the high Alps. Sincere efforts in that direction just petered out. His continuing surrender to God led him step-by-step to become a successful businessman instead—not only a maker of fine watches with his own shop but also a successful investor. His desire to save others was fulfilled not only by those he physically saved from drowning, fire, or in wartime, but by his philanthropies, that included saving people who were down and out financially.

Around the same time, Zélie Guerin tried to take her gift of love for God into a convent but was told, “This isn’t the life for you.” Discerning this was true, she studied and learned a skill—in her case making the luxury good called Alençon lace—becoming a successful businesswoman with a number of employees. Her desires to serve God would be fulfilled not only in the way she treated her employees and those she did business with but in a holy marriage and family. Today, known as Bl. Zélie, the once would-be-nun discovered, “I was born to be a mother.”

Although each had initially planned to live celibate lives in religious orders, Louis and Zélie met and married. Their marriage, rooted in God, was hugely successful, in their deep love for each other, that helped each other achieve spiritual greatness, and also as partners in business (eventually Louis closed his to take over the traveling portion of Zélie’s), in charitable undertakings, and in parenthood. Had Louis and Zélie insisted on entering monasteries, they would have never developed their great talents, not just for business, but for marital love and parenting. Themselves beatified saints, this couple became the parents of St. Thérèse of Lisieux and of Servant of God Léonie Martin.

2. Surrendering to God means giving God all your interior ugliness whether small or large—even those failings and sins still hidden from you—by continually being open to acknowledge imperfections and humbly doing your best to improve.

What this has to do with divine providence can be summed up as clearing space. Assume that your mental attic is crammed with unforgiveness, envy, resentment, and anger. All that baggage, perhaps accompanied by going over your “he/she done me wrong list” obsessively, can leave little or no room in your mind for reveling in God’s goodness, his love for all (even those you hate), his mercy, and the wonderful way he meets your needs. Maybe under your rug is a trapdoor into sexual obsessions you turn to rather than deal with real relationships. That space could hold a lot of God’s supply if you’d let him help you clean it out. Maybe your vault is so crammed with greed, there’s no room for real riches. You get the picture.

This is not a book on inner healing. So let it suffice to say saints are people who, having surrendered to God, have with divine help cleared out all deliberate sin and the majority of their failings. Above all, they have wrestled into submission the pride- and anger-based trip-ups of good people: righteous indignation, helpful criticism, justifiable anger, deserved punishment, and other rationalized nastiness.

The space created is where the saint’s heart, mind, and soul bask in God’s presence and providence. So the more space you create—and this is a lifelong task—the more room you have for God’s providential bounty of every kind.

Okay, so you’re willing to accept that, if not a mean bone, there might be a mean sliver in your body. Surely God will not deny your needs by holding you responsible if you don’t know you have various little meannesses inside? He won’t, but it never hurts to open yourself to the need for repentance and change. To the degree you do that, you will receive from God, just for being open, as if you had already changed a great deal. (Scriptures actually speak about this in a parable of those who have done very little work getting paid like those who accomplished a lot because of the Master’s generosity—look at Matthew 20:1–16, The New American Bible, Saint Joseph Edition.)

BEING READY TO CHANGE

How do you open yourself to being sorry for wrongs and to being ready to change? Cultivating honesty with God—who knows it all anyway and loves you way more than you do—is a key. In my case, I received the grace to pray, “God show me my faults.” Well, the parade has never stopped. But God is as gentle as the best of mothers. He leaves a lot of distance, even years at times, between the revelations. Sometimes a realization arrives like Father Solanus’ bakery man—just suddenly there. Other times insight comes through reading about the saints.

For instance, God once got through to me about gossip through reading about the parents of St. John Neumann (d. 1860), who are among the “hidden” saints of the world. Anyone who tried to gossip in the Neumann home quickly had the subject changed by Mrs. Neumann, and any guest who plowed on anyway was not invited back. I finally got it that all gossip was wrong, including the kind I excelled in, where you and a close friend talk about someone’s faults under the guise of helping them through prayer.

Besides the flash insight or realization through reading, sometimes an area calling for change wells up in prayer. As the big areas get cleaned out, smaller ones come up and old resistances to change fade, seeing how each little bit of progress expands life.

As you ask God for help to live a life with more room for divine providence, remember: perfection is reserved for God alone. Even saints, to protect them from egotism, have imperfections to regret. Canadian Holy Cross Brother St. André Bessette (d. 1937), one of the Church’s great instruments of God’s healings, suffered fatigue-triggered crankiness, and oversensitivity that imagined censure where none was intended. He made frequent use of Confession, God’s gift to those who sincerely want to change. Bl. Louis Martin’s successful investments made him aware that, without watchfulness, he could become too caught up in the pleasure of making money. In Servant of God Dorothy Day’s interviews with Harvard professor Robert Coles (published as Dorothy Day: A Radical Devotion), the founder of the Catholic Worker houses of hospitality is open about many spiritual struggles typical of holy people, among them struggling to serve, as well as to work with, others in a warm comradely, not condescending or indifferent, way, to do good year after year without self-righteousness or pride. In her personal diaries, edited by Robert Ellsberg as The Duty of Delight, Day records such self-criticisms as “I criticize [others while] I justify myself.” The solution in her case, she feels—to avoid the implicit sense of superiority—is to consider everyone better than herself. (Obviously this would not be helpful to those with unhealthily low ego strength.)

Acknowledge but do not be lured into over-concentration on your negative traits. Insight into a fault that leads to self-condemnation is not of God. Recognition of faults that is rooted in God leads to real sorrow for them but concentration, with joy, on changing, not self-rejection. (It is God, after all, who asks us to set the bar at how we love our neighbor by how we love ourselves.) To make the process easier, keep your eyes more on the God of love (and if that isn’t your concept of God, working on that is a good starting place) and less on yourself while you make more room for providence, through patiently and gently rooting out what slows down or halts the growth of your love of God and neighbor.

A LIFE-LONG PROCESS

Surrendering your ugly areas is always a lifelong process. When the middle of Zélie and Louis Martin’s five daughters brought her outgrown dolls to the younger two, the youngest, Thérèse, put out her arms, crying, “I want them all.” The future St. Thérèse of Lisieux gradually outgrew this childish greediness all the way to sanctity. She learned well that it’s hard to receive God’s bounty if one’s hands are full of things snatched in greed, and that there is no need to be greedy if you live in divine providence. In fact, greed says, “I can’t trust God to provide, so I’d better wade into life with both hands and grab my share—and yours too.” Yet many of us who sincerely see ourselves as generous—and who are generous in many areas—have pockets of unacknowledged greed. These may be as simple as always snatching the biggest cookie, or the largest steak from the grill, stealing time at work for long personal calls, or taking office supplies for family use, or as insidious as wresting the last quarter percent of interest from someone who desperately needs a loan in hard times, or trying, perhaps at a garage sale or visiting an impoverished country to get some obviously poor person to sell you for less something you don’t need and can easily afford. People who are basically good may do all these things without thought. But as you more and more desire to surrender, God will gently reveal yourself to you so you can blush and change.

Don’t be surprised if God shows you the egotism mixed up with your virtues. For instance, you may never