Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Poetry

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

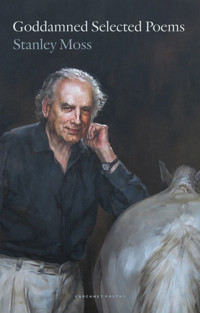

A couple of years ago Stanley Moss renewed his driver's license. Now in his late nineties, his license runs to his 104th year. He has produced such an immense volume of work in his long life that it seemed necessary for his readers, old and new, to essentialise this mass of work into a portable, liftable single collection of highlights, which these 200 pages represent. It has been hard to confine him to this limiting measure because he still, every week and sometimes every day, produces a wholly new poem, surprising his editor and also, always, himself. As he says in 'The Ocean Slaps my Face': Yes, Poseidon, you may call me the F-word, I'm a fluke and flounder. I am a rogue wave, I am a rogue wave! 'Undaunted, outrageously alive,' Rosanna Warren said, 'Moss flaunts more colours than the Grim Reaper ever dreamed of, laughs in his face, rhymes with abandon, makes a joyful noise unto the Lord, and struts with Baudelaire.' He asks what John Ashbery called 'unthinkable questions, but when he formulates them, they take on the quiet urgency of common daylight'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 204

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Goddamned Selected Poems

Stanley Moss

carcanet poetry

Contents

GODDAMNED SELECTED POEMS

Song of Alphabets

When I see Arabic headlines

like the wings of snakebirds,

Persian or Chinese notices

for the arrivals and departures of buses—

information beautiful as flights of starlings,

I cannot tell vowel from consonant,

the signs of the vulnerability of the flesh

from signs for laws and government.

The Hebrew writing on the wall

is all consonants, the vowel

the ache and joy of life

is known by heart. There are words

written in my blood I cannot read.

I can believe a cloud gave us the laws,

parted the Red Sea, gave us the flood,

the rainbow. A cloud teaches kindness,

be prepared for the worst wind, be light of spirit.

Perhaps I have seen His cloud,

an ordinary mongrel cloud

that assumes nothing, demonstrates nothing,

that comforts as a dog sleeping in the room,

a presence offering not salvation

but a little peace.

My hand has touched the ancient Mayan God

whose face is words: a limestone beasthead

of flora, serpent and numbers,

the sockets of a skull I thought were vowels.

Hurrah for English, hidden miracles,

the A and E of waking and sleeping,

the O of mouth. 4

Thank you, Sir, alone with your name,

for the erect L in love and open-legged V,

beautiful the Tree of Words in the forest

beside the Tree of Souls, lucky the bird

that held Alpha or Omega in his beak.

The Lost Brother

I knew that tree was my lost brother

when I heard he was cut down

at four thousand eight hundred sixty-two years;

I knew we had the same mother.

His death pained me. I made up a story.

I realized, when I saw his photograph,

he was an evergreen, a bristlecone like me

who had lived from an early age

with a certain amount of dieback,

at impossible locations, at elevations

over 10,000 feet in extreme weather.

His company: other conifers,

the rosy finch, the rock wren, the raven and,

blue and silver insects that fed mostly off each other.

Some years bighorn sheep visited in summer—

he was entertained by red bats, black-tailed jackrabbits,

horned lizards, the creatures old and young he sheltered.

Beside him in the shade, pink mountain pennyroyal—

to his south, white angelica.

I am prepared to live as long as he did

(it would please our mother),

live with clouds and those I love

suffering with God.

Sooner or later, some bag of wind will cut me down.

The Bathers

1

In the great bronze tub of summer,

with the lions’ heads cast on each side,

couples come and bathe together: each touches only

his or her lover, as he or she falls back

into the warm eucalyptus-scented waters.

It is a hot summer evening and the last

sunlight clings to the lighter and darker blues

of grapes and to the white and rose plate

on the bare marble table. Now the lovers

plunge, surface, drift—an intruding elder

would not know if there were six or two,

or be aware of the entering and withdrawing.

There is a sudden stillness of water,

the bathers whisper in the classical manner,

intimate distant things. They are forgetful

that the darkness called night is always present,

sunlight is the guest. It is the moment

of departure. They dress, by mistake exchange

some of their clothing, and linger

in the glaring night traffic of the old city.

2

I hosed down the tub after four hundred years

of lovemaking, and my few summers.

I did not know the touch of naked bodies

would give to bronze a fragile gold patina,

or that women in love jump in their lovers’ tubs.

God of tubs, take pity on solitary bathers

who scrub their flesh with rough stone

and have nothing to show for bathing

but cleanliness and disillusion. 6

Some believe the Gods come as swans,

showers of gold, themselves, or not at all.

I think they come as bathers: lovers,

whales fountaining, hippopotami

squatting in the mud.

Heart Work

No moon is as precisely round as the surgeon’s light

I see in the center of my heart.

Dangling in a lake of blood, a stainless steel hook,

unbaited, is fishing in my heart for clots.

Across the moon I see a familiar dragonfly,

a certain peace comes of that. Then the dragonfly

gives death or gives birth to a spider it becomes—

they are fishing in my heart with a bare hook,

without a worm—they didn’t even fish like that

when the Iroquois owned Manhattan.

Shall I die looking into my heart, seeing so little,

will the table I lie on become a barge, floating

endlessly down river, or a garbage scow?

There is a storm over the lake.

There are night creatures about me:

a Chinese doctor’s face I like and a raccoon I like,

I hear a woman reciting numbers growing larger and larger

which I take as bad news—I think I see a turtle,

then on the surface an asp or coral snake.

One bite from a coral snake in Mexico,

you’ll take a machete and cut off your arm

if you want to live. I would do that if it would help. 7

I say, ‘It’s a miracle.’ The Chinese doctor and the moon

look down on me, and say silently, ‘Who is this idiot?’

I tell myself, if I lie still enough I’ll have a chance,

if I keep my eyes open they will not close forever.

I recall that Muhammad was born from a blood clot.

If I’m smiling, my smile must be like a scissors opening,

a knife is praying to a knife.

Little did I know, in a day, on a Walkman,

I would hear Mozart’s second piano concerto,

that I would see a flock of Canada geese flying south

down the East River past the smokestacks of Long Island City.

I had forgotten the beauty in the world,

I remember. I remember.

Chinese Prayer

God of Walls and Ditches, every man’s friend,

although you may be banqueting in heaven

on the peaches of immortality

that ripen once every three thousand years,

protect a child I love in China

and on her visits to the United States,

if your powers reach this far, this locality.

You will know her because she is nine years old,

already a beauty and an artist. She needs more

than the natural protection of a tree on a hot day.

You have so many papers,

more than the God of Examinations,

more than the God of Salaries,

who is not for me, because I am self-employed.

It may help you find her to know her mother

was once my bookkeeper,

her brother is a God in the family, 8

who at six still does not wipe his bottom.

Protect her from feeling worthless.

She is the most silent of children.

She has given me so many drawings and masks,

today I offered her fifty dollars for a painting.

Without a smile she answered,

‘How much do you get for a metaphor?’

Sir, here is a little something to keep the incense burning,

remember her to the Almighty God whose character is Jade.

Happiness

One foot on the ground, I steal

what I love from a wordy wilderness,

I don’t rob banks or make dirty deals,

no pick pocket I steal words, your happiness

without taking away your happiness.

I might name a dog Happy but not Happiness.

I peek in on two lovers tethered,

reading, writing, bathing together,

happy opposites and birds of a feather.

Happiness is tongues playing follow the leader

doing unto others as you

would have others do unto you.

I offer shelter to homeless readers.

I still have my voice but I cannot whistle.

Happiness perks my lips so I can whistle

a tune with Irish propinquity. The Irish

can’t speak a word that is not musical.

Unhappiness has a certain authenticity.

The moon and sun are family, 9

darkness belongs to you and me,

the day belongs to no one, the night is ours.

I am frightened sometimes, family history:

I’ll be hit by an armchair or bamboo.

I wake up in the morning with nothing to do

feed animals, write, water the flowers.

Now is the glorious spring of my content,

I will settle for sorrow and contentment.

Felicity, how now pretty lady. Happiness

is a Goddess in China, good news in Ghent,

I steal happiness, impossible flying elephant.

Letter to the Butterflies

1

Dear Monarchs, fellow Americans,

friends have seen you and that’s proof,

I’ve heard the news:

since summer you traveled 5,000 miles

from our potato fields to the Yucatán.

Some butterflies can bear what the lizard would never endure.

Few of us can flutter away from the design:

I’ve seen butterflies weather a storm

in the shell of a snail, come out of nowhere

twenty stories up in Manhattan.

I’ve seen them struggling on the ground.

I and others may die anonymously,

when all exceptionalism is over,

but not like snowflakes falling.

This week in Long Island

before the first snowfall, there is nothing left

but flies, bees, aphids, the usual. 10

2

In Mexico

I saw the Monarchs of North America gather,

a valley of butterflies surrounded

by living mountains of butterflies—

the last day for many.

I saw a river of butterflies flooding

through the valley, on a bright day black clouds

of butterflies thundering overhead,

yet every one remained a fragile thing.

A winged colossus wearing billowing silk

over a sensual woman’s body

waded across the valley,

wagons and armies rested at her feet.

A village lit fires,

and the valley was a single black butterfly.

3

Butterflies,

what are you to me

that I should worry about your silks and powders,

your damnation or apotheosis,

insecticides and long-tongued lizards.

Some women I loved are no longer human.

I have a quarrel with myself for leaving my purpose,

for the likes of you, beauties I could name.

Sooner or later

I hope you alight on my headstone

above my name and dates, questioning

my bewilderment.

Where is your Chinese God of walls and ditches?

Wrapped in black silk I did not spin,

do I hold a butterfly within?

What is this nothingness they have done to me?

Antony With Cleopatra

Certainly our fields were planted

With lilac and poppies

When there was need of cotton and wheat.

So toward the end of summer

We began our walks on the outskirts of the city

To watch for the coming of strangers.

We were not young—but excellent.

What a long way from Italy,

The Nile never seemed so deep;

It was the very brim of summer,

Still the best time of the year for love,

Roman soldiers dived arch-backed into the sea.

Across the Mediterranean came Caesar and ships,

His spikes and axes multiplying the sun,

His sails full silver;

Our sheets still warm and wrinkled,

Cleopatra pretending sleep,

Antony still naked beneath his armor.

Two Fishermen

My father made a synagogue of a boat.

I fish in ghettos, cast toward the lily pads,

strike rock and roil the unworried waters;

I in my father’s image: rusty and off hinge,

the fishing box between us like a covenant.

I reel in, the old lure bangs against the boat.

As the sun shines I take his word for everything. 12

My father snarls his line, spends half an hour

unsnarling mine. Eel, sunfish and bullhead

are not for me. At seven I cut my name for bait.

The worm gnawed toward the mouth of my name.

‘Why are the words for temple and school

the same?’ I asked, ‘And why a school of fish?’

My father does not answer. On a bad cast

my fish strikes, breaks water, takes the line.

Into a world of good and evil, I reel

a creature languished in the flood. I tear out

the lure, hooks cold. I catch myself,

two hooks through the hand,

blood on the floor of the synagogue. The wound

is purple, shows a mouth of white birds;

hook and gut dangle like a rosary,

another religion in my hand.

I’m ashamed of this image of crucifixion.

A Jew’s image is a reading man.

My father tears out the hooks, returns to his book,

a nineteenth-century history of France.

Our war is over:

death hooks the corner of his lips.

The wrong angel takes over the lesson.

The Blanket

The man who never prays

accepts that the wheat field in summer

kneels in prayer when the wind blows across it,

that the wordless rain and snow

protect the world from blasphemy. 13

His wife covers him with a blanket

on a cold night—it is, perhaps, a prayer?

The man who never prays says kindness and prayer

are close, but not as close as sleep and death.

He does not observe the Days of Awe,

all days are equally holy to him.

In late September, he goes swimming

in the ocean, surrounded by divine intervention.

Krill

The red fisherman

stands in the waters of the Sound,

then whirls toward an outer reef.

The krill and kelp spread out,

it is the sea anemone that displays the of,

the into, the within.

He throws the net about himself

as the sea breaks over him.

The krill in the net and out of it

follow him. He is almost awash

in silver and gold.

How much time has passed.

He believes the undulation of krill

leads to a world of less grief,

that the dorsal of your smelt,

your sardine, your whitebait, humped

against the ocean’s spine, cheers it

in its purpose.

The krill break loose, plunge down

like a great city of lights. He is left

with the sea that he hears

with its if and then, if and then, if and then.

A Visit to the Devil’s Museum in Kaunas

I put on my Mosaic horns, a pointed beard,

my goat-hoof feet—my nose, eyes, hair and ears

are just right—and walk the streets of the old ghetto.

In May under the giant lilac and blooming chestnut trees

I am the only dirty word in the Lithuanian language.

I taxi to the death camp and to the forest

where only the birds are gay, freight trains still screech,

scream and stop. I have origins here, not roots,

origins among the ashes of shoemakers

and scholars, below the roots of these Christmas trees,

and below the pits filled with charred splinters of bone

covered with fathoms of concrete. But I am the devil,

I know in the city someone wears the good gold watch

given to him by a mother to save her infant

thrown in a sewer. Someone still tells time by that watch,

I think it is the town clock.

Perhaps Lithuanian that has three words for soul

needs more words for murder—murder as bread:

‘Please pass the murder and butter’ gets you to:

‘The wine you are drinking is my blood,

the murder you are eating is my body.’

Who planted the lilac and chestnut trees?

Whose woods are these? I think I know.

I do my little devil dance,

my goat hooves click on the stone streets.

Das Lied von der Erde

ist Murder, Murder, Murder.

The Miscarriage

1

You had almost no time, you were something

not quite penciled in, you were more than darkness

that is shaped by its being and its distance from light.

(To give birth in Spanish is to give to light.)

There was the poetry of it:

a word, a letter changed perhaps

or missing and you were gone.

Every word is changed when spoken.

The beauty is you were mine and hers,

not like a house, a bed, a book, or a dog,

unsellable, unreadable, not love, but of love,

an of—with a certain roundness and a speck

that might have become an eye, might have

seen something, anything: light,

Tuscany, Montana, read Homer in Greek—

unnamed of, saved from light and darkness.

2

I was not told of you until long after,

I would not have handed down that suitcase

to her through the train window in Florence

had I known. I might have suggested tea

instead of Strega, might have fanned the air.

Fathers can do something. I didn’t ask the right questions.

I did not offer any sacrifice.

I just walked around in my usual fog looking

at pictures of the Virgin impregnated by words.

What if the Virgin Mother had miscarried? What if

the Magi arrived with all that myrrh and frankincense

like dinner guests on the wrong evening?

Our Lady embarrassed, straightening up, 16

Joseph offering them chairs he made and a little wine,

sinners stoned in the street

while John who would have been called the Baptist

wept in his mother’s belly.

Peace

The trade of war is over, no one sings Over There,

but simple murder is still in fashion.

The No God, Time, creeps his way,

universe after universe, like a great snapping turtle

opening its mouth, wagging its tongue

to look like a worm or leech

so deceived hungry fish, every living thing

swims in to feed. Quarks long for dark holes,

atoms butter up molecules, protons do unto neutrons

what they would have neutrons do unto them.

The trade of war has been over so long,

the meaning of war in the O.E.D. is now ‘nonsense’.

In the Russian Efron Encyclopedia,

war, voina, means ‘dog shit’;

in the Littré, guerre is ‘a verse form, obsolete’;

in Germany, Krieg has become ‘a whipped-cream pastry’;

Sea of Words, the Chinese dictionary,

has war, zhan zheng, as ‘making love in public’,

while war in Arabic and Hebrew, with the same

Semitic throat, harb and milchamah, is defined

as ‘anything our distant grandfathers ate

we no longer find tempting—like the eyes of sheep’.

And lions eat grass.

Review

A clothesline

tied from a dead ash to a weeping willow,

my old and new clothes washed clean,

on close look not washed, something to fool the eye,

my stained underwear and holy socks,

blooms of good and evil, and something to fool the ear,

dirty laundry flapping in the wind in meter.

I know bird chatterings are love calls,

‘Rr’ is the dog’s letter.

Why don’t they teach the ‘are’s anymore,

you are, we are, what are we to do?

Clothespinned to the line, my dirty laundry

often tells the truth, not the whole truth,

not nothing but the truth, so help me God.

Laundry makes nothing happen: it survives

in the valley of never-fooled sun and winds

where nothing is said by happenstance.

I babble, trying to honor the language:

‘I am the world, a globe walking with long legs,

cities, oceans, smoking dumps around my waist.’

When the music changes, the fiber optic lines tremble.

I hum the rest, I remember poets who made it new,

swam in the Yangtze, Passaic, Thames and Charles.

Like Hart Crane I wore a bathing suit with a top.

I thought describing the fat lady in the circus,

legs spread apart from the ankles up,

was the naked truth. Why are there no laughing willows?

There are giggling brooks. I heard laughter in the forest,

seven-foot golden bantam corn growing in August.

It sounds like happiness, till 8 p.m. above the Hudson,

when laundry, clean and dirty, is taken in,

when the night creatures I love come out.

The Falcon

My son carries my ghost on his shoulder, a falcon,

I am careful not to dig in my claws. I play

I am his father owl, sometimes sparrow, a hummingbird

in his ear. I told him from first chirp:

‘Be an American democratic Jew mensch-bird.’

When he was a child in Italy I was a migrant bird

with a nest in America. When I flew home

he cried, ‘Perche, perche?’ I wept

not wanting him to have a distant bird

or a sea captain for a father.

How many times did I cross the Atlantic

in the worst weather to perch outside his window?

What kind of nest could I make in Italy

on a hotel balcony? When he needed to be held

his mother and nannies took turns. When he reached out

to me he often fell. He said I know I know to everything

I might have taught him. I fought for his life

with one wing tied behind my back—

for his name, school, and to have his hair cut

in a man’s barber shop, not a salon for signoras.

‘Lose to him! Lose to him!’ his mother screamed.

I was the only one in his life

who would not throw a footrace

he could win in a year, fair and square.

How could a small boy spend so much time

laughing and talking to a father in restaurants?

He complained in Bologna I took him to six museums,

in Florence four, in España mille e tre.

We laughed at those rare Italian birds

who don’t find themselves sleeping forever

on a bed of polenta—preening, displaying,

making a bella figura