7,50 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

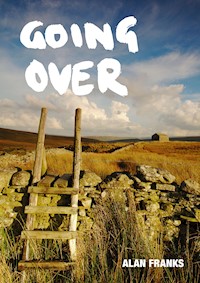

Three novellas of which the the first 'Going Over' won the National Novella Competition in 'New Writer Magazine'. A young man walks across the north of England and, remembering his relationship with his father, wonders if he could have prevented what happened to the family. 'The Tarnished Muse' is a satire on show business and 'The Night Everything Happened' a riotous London comedy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Dedication

For Ruth

Contents

Title page

Dedication

Going Over

The Tarnised Muse

The Night Every Thing Happened

By the Same Author

Copyright

Last year, having finally agreed to see my father, I decided to make a detour first. I suppose there were two ideas behind it. If the trip was a disaster, I could at least tell myself that I had done something else as well. Also, it would buy some time between the easy bit of setting off and the difficult bit of arriving. But how much time, and how much space? Too little and it would just be an extension of the journey. Too much and it would become the object itself. So eventually I settled on a distance of about 80 miles and a time of four or five days, bearing in mind that I was walking. I bet he never had such difficulties with his own calculations, the old sod.

I would pick up the path at the Lion Inn, high up and entirely alone on the North Yorkshire Moors at Blakey. I had already done the eastern section of the coast-to-coast route as a boy of 12, coming westwards from Robin Hood’s Bay via Grosmont and Glaisdale. In fact I had done it with my father in the hot summer that started up so soon after the unmentionable events of Easter, the two of us walking in silence along the flat, empty tops. I had no wish to revisit that occasion as well. This present trip was quite enough to be going on with.

If I walked west from Blakey, as far as Shap, I would have done two thirds of the coast-to-coast and could pick up the final section, across the Lake District to St. Bees Head, on a later occasion. This is how I have always done the long distance routes, collecting them in parts over a series of years: two summers for the Pembrokeshire Coast, three for Offa’s Dyke, and so on.

The routes made their way into my life like good novels, and then helped to define my memories of the periods that surrounded them. It is ironic that if it had not been for my father I would probably not have spent so many long days of my own adult life on the upland paths of England, stalking the deep satisfaction of tiredness and inns. For his part he used to thank J.B. Priestley who, in his book An English Journey, wrote about the meditative properties of walking, the “skull cinema” that comes into play when you put one foot in front of the other and let the miles pass beneath them.

It’s true. When I live for days on my striding feet a kind of hypnosis occurs. The result is an intense awareness of the place, but a removal from the moment. There is a shifting of time. Past events stand up like boulders in the foreground, and present concerns recede to a point on the rear horizon.

Then there was the other old man, Alfred Wainwright. He was the one who pioneered a walking route from one side of the country to the other, all along public rights of way, and was generally reckoned to be a Great Englishman. I took a conscious decision to do my walk without the benefit of his guide book. In keeping my independence from him I was also asserting my freedom from paternal influence. Childish, I’m sure.

Years ago I met Wainwright a few times, always through my father, and heard him complain about the number of people crowding the hills. I wanted to tell him that many of these people went on account of his recommendations but, as so often, I didn’t quite dare. Then he turned his complaints towards bus fare prices, the performance of Blackburn Rovers and the decline of ledger calligraphy in town hall finance departments. “You should be able to frame each page,” he said, “and hang it on your wall.” I seem to remember my father trying to humour him, but this was rather like one undertaker trying to jolly another along. I wondered if they were really only happy in the act of complaining. Some time later, on the radio, I heard Wainwright say he’d drawn the hills so that he would be able to recall them when he could no longer walk on them, but now that he could no longer walk he’d lost the sight to see what he had drawn.

Not long after that he died. Everyone said what a fine man he was and seemed frightened of saying a word against him, even when it couldn’t get back to him. I never let on about hearing him say, not long before the unmentionable events, how he preferred the company of the hills to the women he’d married; or about my father grunting in agreement; or about me hoping that I wasn’t going to turn out like that. I would rather have suffered the consequences of open blasphemy than tell those men that I was going to do a thing a different way from them.

But I’m digressing. I can feel the detours trying to push my story from its course at every turn. If they were the detours on a walking route I could handle them. I could give them their head and be sure, from my years of experience, that I could map-read my way back onto the correct path. But they are not. They are unexpected, unmarked. I do not know where they will go, nor whether they will start to assert themselves as the proper destination, nor even whether they will offer a way back onto the original route. They are as forbidding as they are tempting. I fear and regret them, even though I know my journey would be duller without them. The more I proceed with it, the more I feel that I must lose my way in order to find it. That at least is not a completely new sensation.

I booked a room at The Lion. I did this by phone a week in advance. I have heard too many stories of people turning up there, finding it full, and having to try their luck with the landladies of Castleton. I believe Wainwright writes that “there is a ruin across the road where a miserable night could be spent.” But I am nearly fifty, and solvent, and my days of sleeping like an animal are behind me, I think.

Nowadays, when I am away, I find myself looking at the number of stars next to the hotels in the guidebooks. I give guest houses a miss. No more shiny sausages in the front rooms of widows’ houses. No more framed photos of graduating children. No more baths that run tepid after four inches. I go to places where the little basket of shampoo bottles gets replenished every day. I take them with me when I leave, but I have no interest in the shower caps. I hate the Corby trouser presses, and once immobilised one by yanking its metal arms out to the side. I can’t really say why I did this. It was a sort of indulgence, a very delayed treat for a child that had never managed to misbehave – not properly anyway. I did it because I could – the same reason that gross Americans overeat. I probably did about £30 pounds worth of damage, more than I have knowingly done in the rest of my life. It felt great. I have also had two breakfasts, pretending to be two different people – a swarthy one who gets stuck in at 7.00, and then a clean-shaven one who saunters in at 10.00, just before they whip the stuff away. Not that I’d be able to get away with this kind of thing at The Lion, which only takes a handful of guests.

I took the Newcastle train from Kings Cross, then changed at Darlington for Middlesborough and the little line east to Whitby via Commondale and Egton Bridge. I got out at Danby and took a local taxi up to Blakey and The Lion. I had a bright new Karrimor rucksack, and could see that the driver had me down as a Southern Wanker. I was impressed by the sheer volume of contempt he managed to pack into the words “Walking then, are you.”

The rucksack, I admit, was a mistake. Beth bought it for me in a sale at the YHA shop. As we had only been living together for six months, I couldn’t bring myself to tell her it was horrible – a purple and yellow clash of alarming violence. In those days we were circling our way round each other here in the West Hampstead flat, holding on to the early politeness, terrified of the angers that intimacy was bringing as its inevitable freight.

Now, nearly two years into our unspoken contract, I would tell her how hideous I thought it was. But then now she wouldn’t buy that sort of thing. Or if she did, I would make sure it got stolen, as I eventually did with this one. I know she was only wanting to express her support for this passion of mine. But that was where the problem lay. She thinks it’s profoundly odd of me to go walking when the country is criss-crossed by perfectly adequate roads and railways, and so any expression of support was bound to misfire. Still, I thanked her for it at the time, in the way I had been brought up to thank people.

I should also thank her for making me write this. She knows even less than I do what the contents will be. What she does know is that for the past year and a half, since I came back from the walk and the visit, there has been something pre-occupying me, syphoning my attention away from people and things without warning. It is strange that this should have coincided with the period when she and I have grown so close, so virtually married. Many times, in bed, in the bath, on the heath, I have nearly talked about it, nearly told her everything, and then pulled back at the last minute. And every time this has happened, the resulting silence has been very deep, as deep as a lake, like the silence in which I walked with my father from Robin Hood’s Bay to The Lion Inn when I was twelve and he was the age I am now.

Then, a few months ago, Beth suggested I should write it down. We had just made love. She was lying on her side, with her head on my chest, and I had gone distant again. “If you write it down,” she said, “then it’s out of you. You’ve taken its power away.” This is the kind of thing she often says when she has just come back from her group. It might sound as if I am threatened into cynicism by that sort of remark, but I am not. Anything that makes me savour the divergence between my father and me, rather than dread the convergence, is welcome. Besides, what she says is true.

I even like the other women in the group, although I can understand why Beth is wary of me establishing too much direct communication with them. She thinks I fancy Jo, the thin one who used to be a model, and she is absolutely right, although obviously I would never do anything about it. It would be very hard for men not to fancy Jo.

“You’ll find your feelings change when you write it down,” Beth said. Of course I immediately thought this was her means of getting me to tell her what was on my mind (out of the question), but I was wrong. The following day I began scribbling down some rough notes. I started with The Lion Inn because that was the linking point between the walk as a boy with my father and the one without him as a man. It was the end of the first and the beginning of the second. It seemed to offer me the promise of a structure as I wrote. This structure feels at times circular, at times linear. I say I have to thank Beth for the suggestion, but I find myself doubting whether it will be a matter for gratitude. It keeps taking me into exposed places for which I have no maps. I don’t think I will be showing any of this to her. I believe that I love her. I am less sure that she could she love me back if she found out what I am about to write; if she were to discover the truth of my genetic inheritance.

I nearly find myself writing that I made the journey because my father was in his late eighties and would not go on for ever. But only the first half of that statement seemed true. The reason I went is that Maud wrote to me. She had been his housekeeper for a while, before becoming something more. She certainly moved in with him and possibly married him to make it all look proper. If not, then they were just another man and woman living together, as Beth and I are. I was glad of Maud’s presence as it stood conveniently between him and me. She was nearly twenty years younger than him, and clearly digging in for a substantial Third Age of her own.

Her letter was brief and functional, saying what a good idea all round it would be if the “old boy” and I could see each other. She said she wrote with his blessing, and although I did not disbelieve her I had a notion that she had her own reasons for wanting the meeting. I had very indistinct memories of her, despite being aware of her presence in the village from my earliest days. She came from a family full of women who lived above the shops. They took turns to work in the general store and no-one could remember which was which. They supplemented their income with service of various sorts in the large outlying houses. They had all been evacuated from the little village of Mardale when the water board flooded their valley in 1939. Yet Maud’s name conjured nothing in my mind beyond an apron and a slightly austere head of hair. When I then spoke to her on the phone to fix the date of my visit, she sounded friendly enough, if a little cautious. It was strange to think of her as a resident of that old stone house at the end of the straggling little town, just as I had once been.

The drive from Danby to the Lion Inn took nearly half an hour. There was something perverse and glorious about taking a taxi up into the middle of nowhere on a summer evening. Up and up we went, with Danby clinging to us like a brand name. Danby Low Moor behind us, Danby High Moor ahead, Danby Rigg to the left, Danby Beck to the right, Danby Dale beneath the wheels, Danby Cars on top of the roof. When the inn came into view I heard myself say “That’s it” helpfully, just as I might if I have spotted the right turning in north London.

“That’s lucky,” he replied without a smile as I got out and paid him. I gave him an insincerely large tip and, through my VAT habit, asked for a receipt. He tore one from his pad and gave it to me blank. His face was saying “I know what you lot get up to” as he swung round in the car park and drove off.

As soon as I was shown to my room above the bar I realised it was the same one that my father and I had stayed in thirty seven years before. In those days the place did not regularly take overnighters, and my father must have cajoled one of the staff into letting us stay. As I unpacked my sponge bag, I could vaguely remember him remonstrating with someone about charging for “the boy.” His anger was so obviously bigger than everyone else’s, and so obviously more imminent that no-one ever bothered to question him. It would be like questioning a front of heavy weather. The front may not be right, but it was coming. The absence of challenges reinforced his sense of infallibility. If he was wrong, he argued, then people would tell him so, just as he would tell them. And if they weren’t man enough to speak their mind, then their opinions weren’t worth having anyway. And on it went: north better than south; League better than Union; old better than new; and women running the town halls over his dead body. Of course, this did not explain what had happened between him and my mother, but it helped a little.

I had dinner in the bar of the Lion, with the Ordnance Survey map, Number 93, flapping and falling off the edge of the table. The next day’s places along the route set up a striding rhythm in my head. I cast my eyes across from east to west, as far as the edge of the Cleveland Hills and the beginning of the Vale of Mowbray. After that there would be a whole sheet of OS map, Number 92 before I cleared the Pennines, crossed the Westmorland Plateau and had to contemplate the approach of the old stone house and its disdainful coldness in the height of this tremendous summer.

I could have come at it the other way, from St. Bees Head on the west coast. That would have entailed a straightforward crossing of the Lake District, reliably glorious but full of people. Alfred Wainwright of course was a west-to-east man. I remember my father and him falling into a heated disagreement about the best direction. That must have been 20 years ago, the last time I had seen my father, just before I was 30 and when they were already white-haired old boys with opinions cast in long-vanished foundries. East to west is the way, said my father, because you keep the best until last. No, said Wainwright; always best to keep the weather at your back. My father feigned deafness and they went, literally, their own ways. Now I was going in my father’s direction, and this filled me with ambivalent feelings.

After dinner I settled the bill for the night, knowing I would be up at 5.00 the next morning and gone before the place was stirring. I was in bed by ten. I phoned home and left a message on the machine for Beth, who was at her group. Then I returned to the map and went on all manner of flights across the 1:50,000 landscape, flitting from rigg to rigg, and clearing whole river systems at a hop. High above Spaunton Moor, with the abbey crouching no bigger than a beetle at the foot of it, I could feel myself dropping towards sleep. I was dimly aware of someone singing, but could not be sure whether the sound was coming up from the bar or across all the years since I was last here. It was “She Moves Through The Fair” and it was being sung by a high-voiced man or a low-voiced woman. I could hear some of the lines, about the swan in the evening moving over the lake, and about it not being long, love, till our wedding day. I strained for more, but without success. Whatever stood between it and me became more unbridgeable by sound. If the obstacle was the floor of the room, it grew thicker carpet; if it was the years, they stretched out like a chain of passed valleys.

“The boy should learn to look after himself,” says my father.

“For pity’s sake,” says my mother. “He’s just twelve years old.”

“That’s what I mean, woman. That’s what I’m saying. It’s time he got wise. Time he got tough.”

“And do you think he’ll be interested in dragging himself along those moors in your wake, with you not slowing for him and quite happy to sleep like an animal?”

“Interested doesn’t come into it,” says my father. “It’s what he’ll be doing.”

They think I can’t hear them from where I am. But I’m little and quiet, and I know where to go. I know the places that let the sound of their voices in. There are more of the hearing places when their voices are raised. I can slide up and down the three storeys of our narrow house and not be noticed by them. They are too busy arguing to think about me. Sometimes I dislike her almost as much as I dislike him. I don’t want to, but I do. It’s good when it’s just her and me. She’s soft then. They must dislike me too. I must have put them off the idea of having any more children. I’m quite looking forward to being sent away to St. Bees. There will probably be other boys there like me. Other ones who have done something wrong but haven’t been told what it is.

“You should ask me about it,” says my mother.

“Ask be damned,” he replies. He sounds very angry. “If I say he goes there, he goes.” I don’t know if he is talking about the walk over the moors, or going to school at St. Bees. It could be either. “Who is it earns the money in this house?”

“It’s only you because you won’t have me working.”

“That’s too right I won’t. I won’t have any wife of mine working.”

“It’s no favour you’re doing me, Albert.”

“Who’s talking of favours?”

“Well for love then.”

The word makes him even angrier and through the door I can hear him pacing the flags. The metal bits on the back of his heels come down hard and loud.

“Love,” he says. “What kind of soppy talk is that?”

“It isn’t soppy, Albert.”

“Besides, who d’you think would have you in your condition?”

“What condition is that?”

“And you can’t even see it.”

When I woke up it was a quarter to five. I barely had to stir and the Lion started to creak. At once a dog chain clinked in the yard. Through the south-facing window I was aware of a fantastic dawn coming uninterrupted from the east. I got out of bed to dress and the creaking of the floor sounded like machinery in all that quiet. I padded downstairs in my socks, carrying my boots and rucksack. The place smelled of stale smoke caught in carpets, and a big hollow clock was ticking. I let myself out and saw the sun approaching in triumph like the sail of a land-boat. It was standing low in the sky and the shadows of the outhouses were as big as football pitches.

I set off to the right and was very soon on the down gradient of a fine broad track. Instead of progressing like a normal path, with bumps and improvisations, it went along in smooth and gentle curves, negotiating with the land for the benefit of the traveller. This was the trackbed of the old mineral line, an amazing piece of Victorian engineering that once carried the Rosedale ironstone over the moors to join the Middlesborough-Whitby line at Battersby Junction. I looked at the map and saw that the track contoured its way around these high shoulders at about 1300 feet.

Up here, for a short stretch of the way, you are doing four walks for the price of one: the mineral track, the Lyke Wake, the Cleveland Way and the Coast-to-Coast. That is the habit of open country these days. Old drove tracks and corpse roads become the components of a managed way which is then christened and marketed as a National Trail.

The sun reared up at my back, my stride lengthened, and I was clattering down the track at four, maybe five miles an hour. When I’m going this well, I can’t imagine ever tiring or wanting to stop. By the time I crossed the road near Urra, two hours on from the Lion, I had still not seen another walker. Then the hills got up and started marching off to the west in a straight line: Hasty Bank, Busby Moor, Carlton Bank. They fell sharply away on the north side like a row of cliffs looking out to sea. Except that the sea here was a flat land of big fields and small settlements, with the tangled stacks of Middlesborough standing right at the other side of the view in a haze of their own making. Over Live Moor, down into Scugdale, across Coalmire and Scarth Nick. Then the hills called a halt, and beyond the main road at Ingleby there was nothing but the uneventful plain and the invisible Pennines beyond. The tarmac arrived and the names became tame: Oaktree Hill, Crowfoot Lane, West Farm. I should have stopped for lunch in the inn at Ingleby, but had lost track of the time. The heat baked the plain and buckled the air above it. The miles went mesmerically on. As they did so I waited for the far air to harden into the great barrier of hills which I knew to be there. I waited for it like a sailor waits for the next promise of landfall. I waited and waited, but still the wall did not appear.

“You heard,” says my father. “I’ll not spell it out again.”

“You’re too hard on him, Albert,” says my mother.

“You don’t know the meaning of hard. You don’t know the meaning of nothing. Look at you.”

She inspects herself and looks back at him. Her whole expression is wounded, like a bruise. They are standing on the middle landing, and I can see them from above. He goes on: “Who’d have you? You smell like a distillery every night of the week. And every morning you stink like there’s a dead animal rotting in your gut. I can’t take you to a function for fear of what they’ll think. You’ve taken to shaking in the mornings.”

“If I have, Albert, it’s nothing but my nerves. I’ll be better, I swear I will.”

“You’re only ever better when you take more of your poison. And then you’re gone again, and around it all goes. You’re known for it now. You’re a known alcoholic.”

“What a ridiculous word, Albert.”

“I’ve tried to protect you all this time, but you’ve been on the stagger once too much. Where’s the boy?”

“I don’t know.”

“And there’s another thing.”

“You know how he goes about.”

“You’re not fit. Once too much you’ve been. And all this while I’m trying to keep the lid on finance. Heather at the stores knows.”

“Knows what?”

“Oh, the innocence of you. I’ve told her from now. No more bottles for you. It’s finished.”

“I can’t think what you’re on about, Albert.”

“It’s lies and all now, is it. I’ll have no choice but to cut off the house-keeping and arrange for the boy myself. He’s not here much longer. And no tick for you. No nothing. The disgrace of it.”

When I looked ahead, I saw that the level of the horizon had gone up slightly. The wall of hills was showing itself at last. I was sharply reminded of my present situation by an angry voice telling me to stop where I was. My hand was just about to lift a loop of wire joining two fence poles in a rough gate arrangement.

“There’s stock in there,” said the voice, closer to me now. “You can’t go through I’m afraid.”

The farmer was about seventy, with an old quilted waistcoat even in this heat, and white woolly hair growing out from under his cap. He looked at me and my kit in much the same way as the taxi driver had done.

“It’s a field,” he said, with the plain tone of a primary school teacher.

These days I can go either way on such occasions. It all depends. When I was young I used to be absurdly deferential to people like this, and would gladly have made a detour into the next county so as not to upset him. But now I am more likely to stand toe to toe with them, rattling off the clauses of a by-law which may or may not exist. Twenty years of being an architect are probably responsible. I discovered that when builders told me a particular thing could not be done they sometimes based their arguments on non-existent regulations. It is all a matter of getting off to an assertive start. These battles are won and lost in the opening seconds. I once told Beth about my wimpishness and she said it was all about my father – about how I vested authority figures with his image and then complied with them. Only later – said Beth – had I come to challenge his dominance and then overcome him in conflict. I did wonder whether this was rather hard on the older men whom I had yet to encounter, who were condemned to be treated by me as though they were my tyrannical father. She laughed and said something like “Well, that’s just how it works,” as if I was naif to be questioning such a known truth. So then I wheeled in the figure of Oedipus, guaranteed to raise the temperature at times like this, and said that since I had effectively slain Laius it must mean that the woman I was now with was Jocasta, my mother. Beth wasn’t happy about this, particularly when I said “Do you think we ought to look at this?”

Then we had one of our rows – very infrequent, I’m glad to say – with each of us blaming the other’s family for everything. I wondered whether we were all condemned to land in our parents’ selves, and whether the interim years were just a futile dance of evasion. She said something about my paths only being as they were because of what had been there before, and about how they were not just a connection between places but between times as well.

“If you want to get through,” said the farmer, “the best way is out round the back there, then down that track, where my finger is, and out into Crowfoot Lane where us farmers don’t go straying with our stock where it doesn’t belong.”