7,50 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A comic novel written in the 1st person by a GP recovering from forms, not just drink and drugs but the lethal lures of gambling, power, lust and love.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

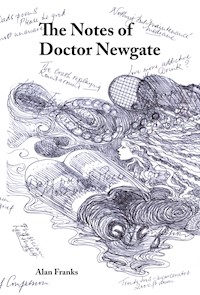

THE NOTES OF DR. NEWGATE

ALAN FRANKS

For Ruth

Contents

The Notes of Dr. Newgate

May 25th 2010. Serena Miller in again. What to do about that one. I have the sense that something dreadful is going to happen to her. We’re all out of our depths with her. She’s one of the bright, canny ones who would play all the members of the practice against each other if she got the chance. All that intelligence, all that charisma, but in such hands. Like a gun. It was all there when she was a girl. Ten years ago now? More? That mischievous face pressed against the window of the squash court while I was losing to her father. That ghastly man. He must have something to do with her present state.

I do wonder whether she’s decided to play the instability card because it makes life so much more interesting. And because she is clearly a gifted actress, whom I expect to see on the West End stage one day. A month ago I referred her to Martina Lubasz, whom I’ve got to know much better since coming through my own recent troubles. Well, not so recent now. How the time goes. She’s not just a very experienced psychiatrist but also – more importantly in my book – a kind and perceptive woman who is better than most at spotting an antic disposition. But now young Serena is back with us, telling me it didn’t work with Martina. I ask her why and she shrugs and says, ‘Because.’ I suggest she gives it one more try, and this time goes along with a more positive approach. She pouts in resentment. Sometimes I don’t know where to start. Nearly twenty years in general practice and still clueless on a regular basis. Quite good at hiding it though, I think.

May 28th. Imogen going through another biting phase. At least I hope it’s only a phase. I wonder whether these phases only become apparent when you, in this case I, go looking for them. I see her this morning from the bathroom, through the crack in the door. Technically, yes, I am spying, and am not proud of myself. Nor ashamed enough to stop. She is my wife - and I am a doctor. Also, I have good reason to believe she has spied on me in the past. For all I know she has taught Inez and all the previous au pairs to do likewise, going back however many years it is since Imogen was expecting Ricky. Twenty-two. So we’re in a climate of mutual surveillance here. Very polite on the outside. Habitually polite to the point of formality these days. But spying away like hell on the inside. As the whole world is now doing. While we were all waiting for Big Brother to install himself, Little Brother slipped in by the back door.

Today is the longest biting session I have witnessed. So, longest since records began, as the weather people say. I’m positioned in the bathroom so that I can see her through the slightly open door. She just sits there in the bed with her hand up at her mouth like something you eat - a sandwich, drumstick, corn cob. But something that never gets consumed. It just oscillates across her mouth and back as she works her teeth against the finger nails. Technically, you can’t really call it nail-biting since that has already been done. So, it’s a kind of ongoing after-sales service, ensuring that the nails will never grow back to the length they were when she started biting them.

May 29th. Same again. Me in the bathroom, looking back into the bedroom; her hand moving hard against her mouth like a harmonica. It would go on for as long as yesterday. As far as I can tell, it would only stop if someone else came into the room - i.e. me at the end of the day, after surgery.

So today I do that - I walk back in from the bathroom to see if the action stops. It does. As her hand goes down, so her face comes up and gives me a neutral acknowledgement. I suppose I’ve become more aware of it since other doctors at the practice – well, one other doctor really, Maurice – decided he was an authority on compulsive and repetitive behaviour of all kinds. Because of his intensely rivalrous nature, I am sure he has only become an expert in this field to let me know I do not have a monopoly on knowledge of the addictive personality. There are many things he will not forgive me for. One is my apparent recovery (caution here, Newgate) from alcoholism. Another, of course, is my wife.

I don’t know if Maurice is aware of her habit, although I couldn’t help hearing him drop the word Onychophagia (technical term for nail-biting) into a phone call the other day. Nor have I missed his recent references to the role of behavioural therapy in Impulse Control Disorders. I remember the time when HRT stood for Hormone Replacement Therapy. Now it stands for Habit Reversal Training. But then I’m hardening into a dinosaur, I know. When I hear LSE I think London School of Economics when I should be thinking Low Self Esteem.

May 30th. Maybe the Onychophagia should be telling me something. Probably something like: ‘Your wife is exhibiting symptoms of stress or anxiety or both, Dr, Newgate, and it is almost certainly your fault.’

Or not. This two-word riposte stands me in good stead when anyone, including me, comes up with a cocksure explanation, particularly one with a little twist of blame thrown in. Arrogant to see yourself as the origin of another’s symptoms. Easier to fall back onto the Anglicans’ secret friend, agnosticism, and accept that your only certainty is that you are uncertain.

Henry Gordon-Venning (HGV to the other three of us as he is as slow and bulky as a Heavy Goods Vehicle) likes to put these fringey conditions down to accidie. Pompous old toad. When stumped, reach for classical archaisms. The ancient marble of authority. Although maybe I did sense something of that sort in Imogen, right from the start. Again, maybe not, since in those days my diagnostic skills were so lacking that I would have needed to see a right angled bend in a thigh before suspecting fracture of the femur. Anyway, pretty soon Imogen was so overjoyed at having Ricky, as was I, that everything else vanished.

So it’s possibly no coincidence that her mood has been slumped ever since he started at Oxford, which is now three terms ago. I go back and back in my mind to the time before she was pregnant. Those two years we had in Hastings, before coming here. I try to remember how she was then - pretty low is the answer. The damp little cottage, her psychotic department head, what was his name - Derek - not to mention my terrible houseman hours. All grim stuff, yes, although fairly run-of-the-mill for the doctor and the teacher who are so early in their careers that they’ve still got one foot in adolescence.

June 4th. Co-dependence. That’s the other new Maurice word I was trying to remember. Actually quite dated now in California, its birthplace, but pretty big in certain parts of the Richmond and Barnes areas. I’m fed up with it and its glib reduction of relationships to the status of harmful drugs. Giving myself away here but what the hell.

June 5th. If I’m going to do this, then I must try and keep the entries regular. Six in ten days and already I’m feeling virtuous, professional, candidate for Great Diarists of the Twenty First Century, nonsense like that. The fact is I’ve never been a diary sort of person, partly because I’ve never had the energy. Also, when you read the things, they are so clearly for publication -which this one is absolutely not - that you can’t quite believe what their authors are saying. An opinion is an opinion, but it becomes something else, like rhetoric, when it is being given with a sense of audience. So, I’m my own reader. I am one hundred per cent of my circulation. I shall write it for me. I shall peer over my own shoulder and try to exert some quality control.

June 6th. That resolution has hardened overnight. I knew this to be the case just a moment ago when I sat down and read the May 28th entry, my second. The one about Imogen and the biting. I appreciate the fact that the author, while hardly a Charles Dickens, is at least doing his best to be forthright and to hold the attention of his reader, i.e. himself. The handwriting could be better, but I’m trying to get it down fast, and if you’re a victim of the teaching fashion for italics, as I was, you have to abandon the aesthetic of the line in the interests of pace. This is my sixth entry in the space of a fortnight. I’ve surprised myself by getting even this far.

June 11th. Even with this small number of entries and tiny passage of time, I can feel something beginning to shift. One other person, says Clive, my lovely, lumbering, Bible-bearing sponsor in AA. That’s all you need; just take one other person into your confidence, and the poison of secrecy is bled from you. I think Clive would like that other person to be him, and if that is the case then he has every right to expect it. After all, it was me who approached him at the St. Stephens Saturday morning meeting.

A doctor, he thought, and his eyes lit up. A real live doctor in Alcoholics Anonymous. And not as an observer but a punter, a full participant. People’s eyes often do light up - the cliché is an accurate one - when they realise that even medics, who are meant to know about addictive disorders, can fall prey to such conditions themselves. God, if only they knew. And I suppose we’re good to have aboard. Like priests, or lawyers or teachers. They leaven the fellowship with that fetching English brand of professionalism. Devout, but not too much. Serious but sociable. It is a similar spirit to the one which has helped hold the afflicted body of the C of E more or less together through its own well-practised frailties.

June 13th. When to do this, that’s the next question. It doesn’t matter, seems to be the answer. I’ll do it when I can. When I think how busy we all were at St. Thomas’s, how we sometimes never slept properly for days and yet found the time to study. If you can live that life, you can live any life. That’s the theory, isn’t it? Weed out the ones who can’t hack it, early doors. So thank you, horrible, sleep-deprived, verge-of-madness, keeling-over-in-theatre St. Thomas’s for your invaluable practicals in pluralism. This scribbling, the black biro and the big notebook, the crossings-out and the notes in the margin - they all remind me of those days. Mixed feelings about them; on the one hand the sense of usefulness and the fruits of a profession; on the other hand, all that future stretching ahead with its infinite caseload of the not-yet-sick.

June 18th. Another biting morning and nothing to do with the weather. Me peering back into the bedroom through the crack, and wishing that I weren’t. I ask myself if I am experiencing revulsion and the answer is no. Curiosity perhaps, nothing worse than that. To my great relief. Imogen has never repelled me, quite the opposite, and I hope that remains the case, whatever the state of our relationship might be. I am probably in some form of denial about the way she looks. No, not her, that’s wrong; about the way I look. That’s where the problem lies, or stands, or walks, whenever I catch my reflection in a public surface. Or rather, whenever my reflection catches me, since it’s always that way round. I never go looking for it. Then, as I decide I’m looking old enough to be my own father, I draw a similar conclusion about her, and it sends me hurtling back into the time of our youth, our first knowledge of each other. I try to stay there, in the scent and danger of it, but I can’t hold on. It slips from me like soap in the bath.

I shall have to come back to this subject later.

June 20th. All right then, now. Of course you don’t see your own alterations as dramatically as the rest of the world. Yes, you do get the odd shock from the cruel refractions of a mirror-lined lift - how dare they make you look at the back of your own neck without prior warning - but if you want a consensual view of what is going on, watch the expressions on the faces of people who have known you well but not seen you for a while. This happened the other day in the High Street, when a little group of what used to be The Young Mums from the NCT classes walked straight past me without recognising me. The Young Mums, for Heaven’s sake, still looking remarkably pink-faced and springy-haired in their Pilates and au pair lives. Only yesterday that we were all going distant with unutterable love for our beautiful, perfect, world-saving, tottering little creatures, wishing the other parents and toddlers well but not so well that their own perfect ones had calculus nailed by the age of six and were premiering a Tippett concerto at the QEH by seven. Now I’ve reverted to being a stranger to them.

No, one of their gazes did meet mine questioningly. There was shock, as if to ask me was I playing a joke of some kind; she was thinking about saying something but we passed before she could put anything together. There was the unmistakable behind-the-eyes glint of schadenfreude, never as good at suppressing itself as it fancies. What was her name? Megan. Yes, I’m sure it was Megan. Imogen was forever Round at Megan’s in those days, with Ricky totally edible in his Osh Kosh dungarees or whatever the latest kids’ fashion statements were meant to be.

June 21st. Pre-sleep sounds from upstairs. The water leaving the basin and a few seconds later rattling down into the drain at the foot of the house. Imogen padding across from the bathroom, and the bed whining slightly as she transfers herself onto it and then into it. The muffled sharpness of the Radio 4 beeps as the ten o’clock news comes on and she listens distantly to the usual stuff about bankruptcy and earthquakes. Maybe down here is where I’ll do this. It’s worked so far. We always said this should be my study since it is directly below our bedroom and so wouldn’t be disturbed by a noisy boy or a late-returning au pair.

I find that I have sympathy for us; for Imogen and me, singly and together. Like I have sympathy for some of the people coming through my door at work, playing their losing hands and heading towards sure defeat with such gameness. What to do with that sympathy for the Newgates, William and Imogen, is another matter.

We are always being told to beware of pity. Someone even wrote a book of that name. Beware of Pity. Stefan Zweig. Mila is horribly good on all this. At least she is certainly better than the other three of us at the practice, all white middle-class males. Maybe the Czechs, and the East Europeans generally, have a much more direct approach to certain diagnostic areas - less cluttered with misguided correctness.

Of course a beautiful person experiences loss when they believe that beauty to be gone. This is Mila talking, and I’m only paraphrasing slightly. She wasn’t discussing Imogen, but a friend of hers in Prague. Still, she might just as well have been talking about Imogen. Or rather, Imogen’s opinion of herself. She - says Mila of her friend - was rich in beauty. In her case literally so; the men who wanted her were always rich in money and allowed her visual form of wealth to make her their social peer. But such an arrangement could not last. The men tended to hang onto their money, unless they were reckless or unfortunate; many of them made their money beget more. Her friend, however, was bound onto a course of diminishing returns. It meant that a kind of bereavement was inevitable - a beautiful woman trapped inside one who was no longer beautiful; the equivalent of an oligarch reduced to living in a hostel.

Leave it there. There’s some conclusion forming in my head but I’m too tired to nail it.

June 22nd. Still not there. What I’m trying to say is that Imogen’s certainty of her own decline is making her act as if it’s an acknowledged truth, even though it’s no such thing. This in turn makes me feel I must be at least partly responsible. And so I get on with the business of being repelled by my own behaviour; the peering back into the bedroom, the breaking-off to splash water about in the basin in a nonchalant, shaving sort of way, giving her no chance of thinking that she might be watched.

When we were young… no. No time for that today. Already running late.

June 22nd. When we were young, I was obsessed by her. Even before I had got to know her, she occupied me all through the days and nights. I mean literally; she took up residence in my head and heart. I would write her name down on a piece of paper, carry it around with me, open it up to surprise myself with the dazzle of it. In the street, at Thomas’s, any time of the day or night, or those long shifts when you lost track of the time and the date. Even the digits of her phone number - her family’s phone number - carried a force that was beyond me. Just a handful of ordinary digits, turned into a kind of drug by their association with access to her. Imogen, from the Celtic for maiden, used by Shakespeare in Cymbeline but probably misprinted in the Folio or whatever. Her father’s favourite name; not because of anything as arty as that but because he was a fan of the American comedienne Imogen Coca. Image, imagine, Imogen.

Her by Pen Ponds in Richmond Park very early one autumn morning, after a medics’ all-nighter on some boat at Teddington, in a silver gown, looking through the mist at the swans. When we’d not been able to get home, and just walked through the small hours, oblivious of where we were heading. The light on her shoulders, the curve of her back, her completely perfect figure. Her name definitely played some part in intoxicating me. I don’t think I would have lost my reason, which is definitely what happened, if she had been called, I don’t know, Cheryl. Names are unfair like that.

I can’t write any more of this, not about Imogen. Not about her when she was young. And yet I know I will have to. I haven’t thought about these things, let alone tried to express them, until now. These entries are starting to organise themselves, as if they don’t really need me. Like I’m getting in the way. Not that I can remove myself.

June 29th. Imogen much better today. No more of the Onychophagia routine this morning, at least not while I’m watching her. Which isn’t very long at all, me having decided that it’s not really on to stare at someone when they don’t know they are being observed. My profession doesn’t give me the automatic right to do that. How would I like it if someone kept doing it to me? As my mother used to say. Poor Mum. Also, I realise there’s a danger that I’m willing her to do the biting so that I’ve got ongoing evidence of her strange compulsions. What am I thinking about? Physician heal thyself. As my mother never lived to say.

The Guardian is rumpled on the bed, much more so than when she’s only read it for the crossword and the sudoku. I might even hear her humming when I come home, although she stops soon after. Two reasons for her improved morale stare me in the face. One is Inez, who is now back from her week in Bilbao. There are Spanish delicacies in coloured wrapping paper on the kitchen table; something called kokotxas, which I am told comes from the jowls of the spider crab; Chorizos and Manchega cheese and bottles of Sangria on the sideboard; a stack of classic CDs by Narcisso Ypes, Andre Segovia, Montserrat Caballe as well as the singers and players from Bilbao. They have faces of magnificent passion and heroic abandon. I look forward to hear them in the house, to play host to the sound of them, even though I know they will make me feel thin and constrained. Some of them she knows personally.

The second reason of course is Ricky himself, who will be back from Magdalen any day now. He’s managed to stay in Oxford for a fortnight after the end of term, either in college or in the spare room at a friend’s lodgings. He’s using the libraries and generally enjoying the town until it gets overrun by tourists and he finds himself turned into an unwilling attraction. The weather always brightens on Imogen’s brow when he’s due, just as it did twenty-two years ago. Every return he makes is like a smaller version of that first, great expectation. How will he be this time?

You change like a foal when you are a student. Being a late developer, as I was - am, he looks like a variant of himself after every gap of eight weeks; you blink and he’s put on yet more inches. Surely he had enough already. His face is half-hidden behind a shoulder-length tumble of Merry Monarch curls. Blink again and it’s vanished; he’s as jar-headed as a G.I., with his shoulders made huge and muscular from rowing in the college eight. The culture and the politics keep pace with these wild style swings. Now he’s a classic economic liberal with whole chunks of The Wealth of Nations committed to memory; then, just as suddenly, I’ve nothing to lose but my chains (at least this carries the acknowledgement that I do actually work for a living), and Uncle Karl is his virtual godfather.

So I am waiting to be slain like Oedipus, in the full knowledge that this is the natural order of things and therefore not just good for Ricky but a growth opportunity for me as well. I don’t yet know what form this necessary killing will take, nor what percentages of the literal and the figurative will be there in the mix. I love the boy. Unconditionally, I’m sure, in that if he felt the need to trample all over me, or ignore me, or use his friends’ cyber skills to void my current account in his favour, I would be rooting for him. Smarting a little perhaps, but fundamentally on his side, infuriating him yet more with this show of self-denying liberalism. If it’s any help to him, I do manage to annoy myself just as much as I must annoy him.

July 4th. Ricky duly back from Oxford and Imogen visibly improved. Surely no reason to look any further than Empty Nest Syndrome for the source of her apparent anguish. The real question is what will happen when he’s gone for good, in the sense of married, own home, own children. I can hear Clive’s voice in my head, going ‘Day at a time, William. Day at a time,’ all flat and safe as a mattress. Right as ever. Dull but right.

Ricky’s hair is sticking out in batches. There is a hint of orange which fades as it gets to the root. I deliberately don’t comment on it. I can remember something similar happening to my hair at about that age, when the man in Ginger Group pulled it into swatches which he then wrapped in tin foil until I looked ready to pick up signals from Saturn. For some reason he took it into his head - or rather, onto mine - that this was My Look. I managed to keep my eyes off the mirror until he’d done. It cost me about a third of my grant for the term, and I went straight to the public baths at Kensal Green to wreck it in the showers. No such problems for Ricky, who obviously went clear-eyed into the operation.

I approach him in the kitchen with my arms out a little so that they could just be greeting him or else ready to turn into a full hug if required. Instead he shakes me by the hand in a quaintly formal way and says ‘Hello old man all right.’ Hugs must be for friends only. He smiles very openly, as he always did. There’s the slightly crooked mouth - amused, yes, but with the possibility of reproach as well. It’s a look that tells me I’ll get dealt with before too long. Not destructively perhaps, but with the attention of a younger, stronger, more battle-ready intellect than mine. Than mine ever was.

Inez comes in, surly as ever. Is it only me who sees her like this? Possibly. She hardly acknowledges me before greeting Ricky, who practices his limping Spanish in reply. They laugh, both enjoying his lack of competence. Her face is split across by that frighteningly big mouth with its tight rows of pearl tombstones.

I hear myself say ‘How’s tricks then?’ and sound distressingly old. He and Inez giggle. I guess they’ve found a shared joke in my mannerisms. I don’t really mind. At least I don’t think I do. Imogen gets busy with the tea things, shooting little glances at our big, almost finished son. Our undoubtedly handsome son. They contain love, of course, and a softness which I find myself envying. But there also, unless I’m over-reading her face, is the certainty of imminent loss; the half-formed question of how and who to be in the still-long future; how to relate with this man across the kitchen once their beloved charge is no longer that thing and the shared project of his development is terminated.

Inez helps her with the tea stuff and the three of them sit at the table. There is no fourth chair. It’s not actually a pointed exclusion of me; I don’t think. The other chair’s gone somewhere else, and besides, it’s coming up to two thirty and afternoon surgery.

Later on, when I get back, they’re still at it. A bottle of Inez’s Sangria must have come out because that unmistakable slurpy swinging quality has got into the conversation. Even Imogen who had come in is animated, as she hardly ever is with me. One voice interrupts while the other, the interrupted one, pays no attention and carries right on so that the exchanges are not so much antiphonal as simultaneous.

Everything is the fault of the Baby Boomers, seems to be the gist. Yawn, frankly. Not that it’s not true of course; just that it seems to be the only song on the juke box. They, the Boomers, rolled through the post-war years like a mighty wave and now the children are having to pay for their parents’ indulgences. They got free higher ed, for heaven’s sake. Not loans but grants. Grants. Where do you hear that word these days? They danced till dawn to the best bands the world had ever heard; they smoked grass which bore no more resemblance to the murderous skunk of today than does Babycham to raw poteen; they saw history’s window of opportunity opening between the pill and AIDS and clambered on in. Some never came out again. Others had the high and left their kids the hangover.

It’s a fashionable enough argument, verging on received wisdom. Which is not to say it’s a wrong one. Or a right one. Loads of socio-economic underpinning of the kind which is probably second nature to Ricky and his fellow PPE students: illusory wealth of house price inflation; long-term student debt; decline of the employment market; growing divide between rich and poor. There’ve been whole books about it. Whenever I read the reviews, I feel personally targeted by the argument. I expect the net to close around me, and to learn that I alone have been responsible for the decline of the manufacturing base in the East Midlands. ‘Most culpable of all in the great plundering of the nation’s youth to fund the continuing ease of the greediest generation in our history is Dr. William Newgate of 127 Elm View Crescent, Richmond, Surrey. At a time when longevity is taken for granted and the Boomers’ lives turn into a monster-fade of hypochondria and ruinous state provision, Dr. Newgate truly is the Hey Jude of licensed scrounging.’ Imogen seems to have been given a free pass, but that must be because Inez and Ricky see her as an ally by virtue of her opposition to me. My enemy’s enemy and all that.

If I loiter long enough in the hall, I feel sure a line of ad hominem attack will become audible from the kitchen. I imagine Ricky twining his hands magisterially beneath his chin and rounding up the excursions of the seminar with an admirably plain form of words, as in: ‘Basically I blame Dad.’

Instead I can hear Inez taking it international with an indictment of the English colonial legacy and then Imogen, to her credit, saying that Britain wasn’t going to take any lessons from Spain on the exploitation of overseas possessions. I always loved that forthrightness of hers. It was dangerous and principled, such a welcome change from well-schooled diplomacy. She never knew how to stand down. Ricky says ‘Actually, Mum’s got a point,’ and Inez makes an odd, disconnected noise like a cat getting caught in a closing door.

I don’t think I know anyone else who has children in their twenties and is still keeping an au pair. Certainly not round here, and yet round here is precisely the sort of place where you’d expect such behaviour. For some reason we never stopped. Before Inez, it was Agnieszka from Poland, and before her Marie-Claude from Lyons, and back and back in almost apostolic succession to the original Inez, also from Spain. Not Bilbao though. Valladolid, I think. I called her Saint Inez because of the miracles she worked with our unusually demanding baby and his seriously depressed mother. Like she’d experienced something similar at home.

We just went on replacing them as they left. As Ricky grew towards his teens they stopped being au pairs in the usual sense and turned into hybrids of cleaners, shoppers and general companions for Imogen. Someone once suggested to me that she clearly wanted a daughter without the trauma of bearing one and bringing her up. A therapist who’d turned up at a Pfizer drug lunch in Putney. He even asked me how their presence impacted on my relationship with Imogen, and looked pleased when I said I hadn’t thought about it.

It never seemed to matter that the au pair’s conversations were hampered by language barriers. The conscientious ones took it as an opportunity to improve their English. The rest just spoke in their own language so that by the end of their time with us our Spanish had improved remarkably while their English had got even worse. Ricky always helped out if they wanted slang. He sent the very straitlaced Limoges girl, Francoise, round to Cyril Pegg’s, the family sweetshop, to ask for a Bum Bandit, which he said was the name of a chocolate bar.

This present Inez is no saint. I can’t work her out. But then I could never work any of them out. They always belonged in Imogen’s province. And Ricky’s to a lesser extent. Particularly Agnieszka, who was after him, and endeared herself to us all by getting her plumber cousin to come down from Luton and fix the rebel toilet at the top of the house. A huge saving, unless you take into account the flooding and the cost of the new carpets. If I were twenty-five years younger, I would probably be very drawn to Inez, as Ricky clearly is. I wish him better luck than I would have had. The ratio at Oxford is still so much in favour of the girls, never mind all the secretarial colleges and language schools that flocked there in the hope of some reflected standing.

God I’m exhausted.

July 5th. Still exhausted. I’ve had the Underground dream again. Or part of it at least. The bit where the train’s actually coming into the station and I know what’s going to happen.

Then I must have woken up, or else the rest of the dream must have gone underground, so to speak - carried on in the dream section of my head without alerting the other section which records and memorises the action. When I wake, I’m aware of straining after the sequence of now-familiar nightmare events, almost as if I am following the train into the tunnel against my better judgement. Back to this when more time. Too big for now.

July 13th. Serena Miller in again. Last patient of the afternoon. She must have phoned and got the temporary receptionist, Gill, who then must have slotted her in at the end of normal surgery without letting me know. It’s happened before, although this is the first time with Serena. My fault really. I’ve always said I’d rather see them than not. She’s a welcome sight, why pretend otherwise. With her tossing hair, all full of springtime and youth, and, in utter defiance of her life-style, the figure of an athlete. A swimmer perhaps, sinuous but fluid. Well, she was once, wasn’t she, when she was about seventeen. Long-legged and broad-shouldered, without being remotely manly. You can’t help noticing these things, particularly not after an afternoon’s procession of the folded-double and the frame-assisted insects. The depression which brought her back here seven weeks ago has led to her taking a term off her drama course, with the college’s agreement. They clearly think she is exceptionally talented, and will achieve great things when she sorts her present troubles out.

Serena - I should say Ms Miller but find myself preferring to say Serena - single-handedly brings down the average age of the afternoon’s clientele with a bump. She is only the second under thirty. Almost all the remaining fourteen patients were maintenance jobs; old cars still kept just about roadworthy through replacement parts and medication. And that undoubted sense of entitlement that the ancient and ageing seem to have acquired in the last few years. The entitlement to life on a permanently renewable basis. Like a club subscription that no-one is authorised to cancel. On the few occasions when I try to tell them in the kindest and most diplomatic language I can find that the Reaper is getting restless, they look at me as if there has been a mistake and all that needs to be done to rectify it is a second opinion or a new part and a different tablet. Some of them have seen off so many terminal onslaughts of this or that that I can quite understand why they’ve decided the Maker has lost interest in meeting them, and resent the suggestion that he’s sniffing around again.

The Underground is passing through my head as Serena comes in and takes a seat. This must be making me furrowed or distrait because she asks me if I am all right. Enough emphasis on the ‘right’ to make me think she suspects I am not. Which is presumably the idea. I hate it when patients do this. Just because I ask how they are does not give them the right to ask how I am. Information about them is my stock-in-trade, not a component of social exchange. I am aware of being and looking immensely tired. All day I have tried to avoid a mirror or any remotely reflective surface in the certainty that there’s nothing in it for me; just the dark crescents under the eyes and the stubborn outcrop of slept-on hair.

I must look startled by her. I am. She notes this, sniffs disapproval and then pushes her hands out like buffers, reversing out of the question she has just asked. I say ‘Fine. Thank you. More to the point…’

She laughs and nods and says: ‘Not fine, actually. Not fine at all.’

‘It’s a lazy word, I know,’ I go on. ‘I do rather wish I could come up with a better one.’ I don’t add that one of the many mantras of the fellowship is that fine really stands for fucked-up, insecure, neurotic and egocentric. A bit glib, a bit tiresome but, as ever, not that far from the mark. In her case, bang-on, I’d say.

‘So…’

‘If I were fine,’ she says, ‘I wouldn’t have come again so soon, would I.’

‘No. I suppose not. So. The same, is it? Broadly, the same as…’

I call up her entries and start scrolling down for my notes on her last appointment.

‘The same, yes,’ she goes on, ‘but at the same time different.’

I am aware of her studying the side of my face and being amused by what she sees there. It must be something I give off, the same something that made Ricky and Inez exchange their giggling faces when I was talking to them.

‘You saw Martina,’ I say. ‘I mean Miss Lubasz.’

‘Yeah,’ she replies, bored and impress-me. ‘I told you.’

‘And?’

‘And what.’

‘Can you just refresh my memory. Some of the issues that seemed to be preoccupying you when we spoke before. I presume you raised them with her.’

‘Not particularly, no.’

‘I see. Not particularly. Why was this, if I may ask.’

‘Didn’t come up.’

‘Didn’t come up?’

‘With talking, right? It takes two, yeah. Martina didn’t really want to engage.’

‘No. I see. Well, you know, the thing is. People doing what she does can only be effective if the patient, that is if the other person, will, as it were, well, speak to them. Were you able to say anything to her?’

‘No. Not really.’

‘Nothing at all?’

‘Nothing of any interest. Well. She seemed quite interested in music, and so that was OK, but then it dried up. I’m not very well up on Mahler.’

‘Ah yes.’

‘And she wasn’t into Indie bands.’

There is a silence. She looks at me with her chin slightly up and a what-next challenge in her eyes. She looks a lot better, a lot happier than she did when she walked in a couple of minutes ago, just as I must look a lot older, a lot more tired.

‘Of course,’ I say, ‘there is no compulsion for you to see Miss Lubasz. All I am suggesting, as I think I did when you were last here, is that it is strongly advisable for someone in your situation to open and sustain a dialogue with a qualified professional. That is what they are there for.’

‘I did try,’ she says with sudden emphasis. ‘I did.’ She is almost shouting. ‘I mean, I don’t like it when people are awkward. You know, just two people, so they have to talk. Not like now, which is fine. But with her, right, the truth is I just didn’t know what to say to her. I didn’t want to offend her.’

I laugh slightly, which in turn offends her. I shouldn’t find it funny, but I can’t help it - the plain comedy of someone not knowing what to say to the shrink. Having to make stuff up, even. Hardly the first time. Perhaps Martina was not the right choice. Perhaps I made it hurriedly because I like and trust her. I apologise for laughing and am about to try and explain why I was doing so when she gives out a big, rather bawdy laugh of her own and agrees that it’s got its funny side. This strikes me as progress, although what direction we’re moving in I’m not sure.

I resume the scrolling through her notes and find that on her first appointment with me, five months ago, she was talking of something in her life that was too big (her words) to tell anyone. I also see that I asked her whether that secret was responsible for her having used cannabis and amphetamines at various times in her past - she insisted it was all in her past, although I wasn’t convinced. I’m still not. She answered that that could well be the case, although, she claimed, it was surely for people like me to find out. Already evidence of what I hear again today - some desire to get our profession to show its metal, sing for its supper, something like that.

The screen picks this moment to freeze. Maybe it’s the whole practice going down, as has happened before. More likely just mine. Our technology’s like that. It only has to see me seating myself before it and it comes up with a package of humiliations. Like anyone whose soul is stranded in the mechanical age, I respond to the freeze with more and more clicks and key strokes. To which the screen responds by having nothing at all to do with me. It will not trade with someone quite so disrespectful. I am an embarrassment to the lovely virtual salons of e-speech.

My hands close on either end of the keyboard as if I plan to use it violently against its own computer. The lines and page borders are beyond instruction. They are decomposing and jumbling so that they look like the remains of a crow on a windscreen.

Then my glasses help the anarchy along with a stand-by routine from the low tech days, and fall off my face onto the desk. I comment urbanely on the strange march of progress from the radiogram days when you had to wait for the valves to warm up, to this present time of intelligent people unable to switch a TV on, but she is leaning forward with a hand across her eyes and her face almost covered by the curtains of converging hair.

She is shaking, and I realise that while I have been busily losing my latest computer war, she has been overcome by these unmentionable troubles of hers. This is good, in a way. Painful of course, but better than letting them burn her inwardly and in silence. Perhaps we should persevere with Martina after all. Another mighty mantra from the fellowship falls into my head - Remember, William, you’re as sick as your secrets.

You’re also the world’s worst diagnostician, Dr. Newgate. Those aren’t tears, but the heavings of hilarity. Her turn to apologise, and she would if she could get the words out. No chance. Whenever she draws breath to speak, the air is hijacked for the laughter, whose need is great. ‘I’m sorry,’ she manages eventually. ‘It’s just that… it’s just that….’ But she only has to try and explain why she is laughing (very simple: me) and it makes matters even worse. Toxic Mirth Syndrome. Recovery is slow. She and the computer are level-pegging on the road back to normal function. I can hear Gill in the corridor. Gone closing time by several minutes and she is checking the place for left items and lights still on. She passes slowly by my door and I can almost hear the curiosity in her tread.

‘Well, ‘I say to Serena, who now looks every bit as tousled and blotchy-eyed as if she had just weathered a major emotional hurricane. ‘I’m glad I’ve been able to, erm, entertain you.’ Only the truth. I’m delighted. And goodness how her face catches fire when she smiles.

I decide to carry on. ‘Listen, if you were going to apologise for laughing, there’s really no necessity.’

She looks at me anxiously, expecting some but-clause to come in, some reminder that we have to trade in the adult world and cannot hide behind the diversion of laughter. It doesn’t come, and this surprises her. ‘Actually,’ I say, ‘I’m very glad if I make people laugh, even if I’m not at all sure how I do it.’

The anxiety gives way to the warmth of relief. ‘Thank you so much,’ she says.

‘Not at all.’

‘No, I mean, thank you for seeing me today. I didn’t think you would.’

‘What made you think that?’

‘Oh, you know.’

‘It’s what we’re here for.’

‘Yes. But people don’t.’

‘Don’t what? See you?’

‘Yes. It’s not easy, is it.’

‘What is not easy?’

‘Any of it.’

‘No. I suppose not. You mean, being well.’

‘Yes.’

‘No. Not easy at all. But worth it surely. Worth it in proportion to its difficulty.’

She nods ruminatively. Her face is much as it used to be all those years ago when she and her sister pressed their noses against the squash court window while I played their father, by far the most aggressively competitive member of the club. They would breathe on the glass, then write things on the mist with their fingers and dissolve into helpless laughter. The spasm which she has just had takes me back to those occasions. Brian Miller steeling every sinew for the next point, me affecting languor and complimenting him on his strokes, the girls up in the window falling about at their unaware father. Or was it me? Beyond these scenes, I knew nothing of them or their father. Brian himself was so focussed on victory that he never had the inclination for a drink in the bar; just a shower in silence followed by some elaborate routine with embrocation and bandaging. The nearest we got to conversation was him doing a rigorous critique of his own backhand boast shots.

There was a mother. A mournful, slight woman who only very rarely came to join her family at the club. I saw her on a handful of occasions, each time looking more spectral than the last, nursing a drink as if it was an injured bird, right over in the far corner of the bar while the girls watched their father on court.

I remember that she was admitted to The Priory for depression. I think it turned out to be one of those conditions which mask an addictive disorder. In her case it was plain old alcoholism, which of course was exacerbating the depression while posing as the cure. She was referred by old Dr. Montague, whom I knew a little.

Since then I’ve realised how impossible it was for me to discuss such addictions dispassionately as I was suffering from one myself. I would go through the motions, nod liberally at the praise - the sometimes grudging or patronising praise - bestowed on AA, and wait for the topic to pass. Physician heal thyself indeed. Eventually she just vanished, as I remember. I suppose everyone just vanishes in the end, but Mrs. Miller seemed to diminish, physically, to the point of transparency, as if she had no wish to be seen. She relapsed and died. Alc and barb, but an open verdict at the coroner’s.

There is little of that poor dead woman in Serena, who has the broad frame and athletic face of her father. I wonder how she coped with her mother’s death - whether her present troubles are a result of her not dealing with that loss and its implications. Open verdict maybe, but, as I never stop hearing in the rooms, alcoholism is nothing if not a long suicide note.

I’ve never worn the idea that people can read each other’s minds. Synchronic initiatives perhaps, based on the laws of probability, but actual reading, as if the face is a page of print, no. Which is why Serena’s next remark alarms me so much. ‘You could have gone the same way as her.’ She says it matter-of-factly, as if she has been running a cursor along my lines of thought and has now reached exactly the same place as me. I am aware of looking startled, and try to counteract this with an innocent ‘Who? The same way as who?’ Serena laughs to indicate that she knows who, but then comes to my aid with the information. ‘My mother, of course.’

So Serena knows about my alcoholism - and my recovery from it. Does it matter? Do I mind? I haven’t time to interrogate myself fully on this. No reason to worry though, surely. Sick as your secrets and all that. The healing powers of glasnost. I do know doctors who go to elaborate lengths to keep their addictions - their past addictions - secret. Like travelling thirty miles to go to meetings in neighbourhoods where they won’t be recognised. The wrong policy surely. If this programme of recovery is good enough for a middle-aged, fairly conventional family doctor, shouldn’t it be good enough for anyone? And shouldn’t this fact be known?

My thoughts run back to her father and a particularly unpleasant, ill-tempered three-setter we once had. Again she appears to have stalked me in this shift of concentration from one parent to the other.

‘You know he fucked us,’ says Serena.

I hear myself replying quite coolly - something about Philip Larkin putting his finger on the inevitable harm caused by the parenting process. As I do so, I’m aware that it might be the wrong answer. Or an inadequate one. But then, when people, young ones mostly, say someone screwed them, they usually mean screwed up. So the f-word might also have shaken off the ‘up.’

‘No, no,’ she says. ‘Me and my sister. He fucked us. You remember Charlotte.’

‘Yes. No. Not really.’ True. I don’t. They had the better of me, looking down through the wire-meshed window. To me they were two young, rather spirited girls. There was barely more than a year between them, and I doubt I could even tell them apart. They hunted as a pair and were a single entity. They may have watched me banging about the court after their father for forty-five minutes on end, but I hardly saw them, except briefly, in the family room. I simply didn’t know them.

‘That was a terrible shame,’ I hear myself say. ‘Really awful.’

‘Oh yes, that,’ she replies, realising that I’m referring to the tragic death of Charlotte in a skiing accident in the Bernese Oberland, eighteen months after their mother had died.

‘More than a shame. Much more than a shame.’

There is another a silence, a really long one this time, for the good reason that I can’t think of anything to say, and she is apparently happy not to. I try and weigh the moment just gone. The patient appears to be telling me that her father committed incest. Not just with her but with her sister also.