7,50 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

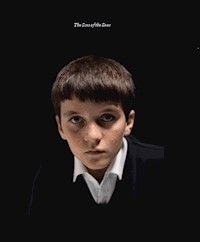

A novel that charts a passionate story about the losing of innocence and the bitter gaining of adulthood. It is also a painfully acute account of a young man's attempts to redeem himself from the ravages of guilt. The period is the early sixties. The Twist the latest dance craze has just arrivd from America and is taking Britain by storm.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

The Sins of the Sons

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part 2

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

By the Same Author

Copyright

| The Sins of the Sons |

When the trouble arrived at his father’s house, Oliver and I were in the Regency Suite of the Mountcrest Hotel, learning to dance with Miss Tench. To be more accurate, we were learning to dance with each other because the year of our birth had been a thin one for girls in the Parkborough district. As I was slightly taller than Oliver I used to take the male part, and he did the same on the grounds that he was already shaving quite regularly. We were probably doing the Foxtrot at the time. The Foxtrot or the Waltz. We never seemed to get beyond them. When Barry Higham, who already went out with girls, said.

“Please Miss Tench can we learn the Tango?” her mouth went into a big lipsticky O, as if she had heard an obscenity. It didn’t much matter which dance we were doing because after a few steps they all turned into locomotive routines with two drivers fighting for control. Wherever we started off, we always ended up shunting into a pillar.

I’d love to say the steps have stood me in good stead in all the years since then, but I think I have only ever used them the once. That was in an emergency at my cousin’s wedding in Harrogate when I was pulled from my table by a very powerful relative and sort of dragged along in her wake. On the basis of these calculations, the Miss Tench lessons were not a good investment. Parents kept saying their was no greater joy than moving in harmony with another person, and looked truly puzzled when this caused shifty laughter. Only Oliver’s father, Benny Jacobs, was blunt enough to say it was the best way to get your hands on a girl and no questions asked. The 1950s, not long finished, had passed itself off as such an innocent time, and nowhere more so than where the leafy suburbs of London turned into the Home Counties. I’ve often wondered whether the national recovery, for reasons I was not meant to understand, depended on the grown-ups’ ability to regain the naivity of childhood. Miss Tench herself sidestepped togetherness. No boy, girl, man or woman had ever been seen dancing with her.

Even with the volume wound up to distortion, it came nowhere close to filling the space. It was about as effective as the single-rung fire that hung on the fleur-de-lys wall.

The tunes struggled to keep their shape in the tinny blur. They made a creamy, yearning noise which filled her face with distance as she took the floor with her perfect partner, the air.

She mouthed the steps into his ear, just as he had done for her in the months before he fell on the beach at Arromanche, 17 years before. I still wonder whether, in that winter of 1962, Miss Tench knew that her Nemesis in the form of the Twist was crouching just round the corner and that the old order was about to pass for ever. I wonder if she had violent dreams and premonitions, like landed matriarchs in the summer of 1914. Even in the Regency Suite of the Mountcrest, it seemed that Miss Tench was already half in love with oblivion, and that nothing could really hurt her any more. Anyway, that is where I was with Oliver on the morning the trouble arrived in his house and in our lives.

There were usually about eight boys and three girls. Barry Higham always got a girl to dance with him, and even managed to get one of the others to dance with his his acolyte John Leers, who was easily the ugliest one there. I could never work out why Higham, who had such confidence and such background, needed Leers so much. Then there was Rickie Lyle, who became a merchant banker, and Florian Dykes, who went into textile design and had magazine profiles about him before he was 25. There were others, but I forget their names. Of the girls, I best remember Emma Gilberdyke, for the obvious reason that she was at the heart of the trouble, and Kate Spatt because of her size and the difficulties which that created for us all.

When the dancing class was over Oliver and I walked back to his house through the Shades.

This was an obscure part of the hill, set back from the houses and overhung by the low branches of four enormous cedars. There was a converted workhouse there, occupied by people of a great age. One of these was said to be a man there with no face, another woman with a large garlic growing from her cheek. We used to approach the Shades through a hidden gate at the back of the hotel car park. Our understanding was that if we saw the woman with the garlic wart, bad luck was on its way. She had once walked along Hill Parade and all the shopkeepers had locked up, some of them so quickly that the customers were trapped inside. They could see the flaky white skin of the garlic and the indentations between each clove as she passed by. If things did not happen as they did in the next few months, I might think we had imagined her. When I questioned Oliver on the story about her and the shops, he said he had heard it from me, while I was certain I had heard it from him. I suppose there were people in the Shades who lived in the penumbra between the main road and our imaginations. When Oliver and I went that way it was always to call up the uncertainty and slurred fact that hung there. The perceptions of the world beyond suspended themselves, and whenever we came out the other side into Oliver’s road our heads were so full of outrageous possibility that we hardly talked.

It was in this condition that we found ourselves standing facing Mr. Jacobs in the huge drawing room.

“So. Oliver. Will you now please tell me what this means? What it is, the significance of this.”

In one hand he was holding a note that had been painstakingly written out in anonymous capitals.

This was evidently the covering letter for the glossier items of similar size that he was holding in the other. They looked to me as though they were photographs of some typed document. It became impossible to glean anything more as he started batting these things back and forth like flippers. The envelope in which they had all arrived fluttered down to the floor. This was also addressed in capitals. Some of the characters had almost been embossed by repeated strokes. None of it looked professional. There was the ghost of a k still protruding from the c of Jacobs.

Oliver was doing his best to identify the documents. His head was swinging to and fro as if he was trying to follow a ping-pong match.

“How can I tell you what it means,” he said,

“when I haven’t even read it?”

“And for insolence, Oliver, there is no need at all.”

“I am not being insolent, father, I promise.”

“What need is there to read it, when you haven written it?”

“Me written you a letter? But why would I do that?”

“No, no, no. This.”

He gave an extra shake with the hand that held the photographs. Then he let the note fall to the carpet, and concentrated on the little pile of photos. He leafed through them, pausing here and there to wince or to let out one of his high and distinctive moans. Sometimes the whole pain of history was in those little noises. The history of his family, the countless cousins who had remained in Eastern Europe at the wrong time of a merciless century; and the larger history of the continent’s jewry, forever at the edge of annihilation. Oliver had once tried to tell me the story of his father’s arrival here as a young man in the 1920s. There were hellish kitchens, sleeping among rats, language problems, the first little venture with his old friend Pawlikowski. But beyond this the details were blurred, and I could not tell if this was because of Mr. Jacobs’s sketchy account or Oliver’s loose grasp of the circumstances. I was intrigued, but never again asked him about it for fear of intruding on private ground. This worry about trespassing was all the stronger when I was in their house.

I focused on the images in his hand, and my suspicions were confirmed. They were photos of pages from a letter. I could see the typing stop above some familiar squiggles of handwriting. There was also a photo of some illustration, but I could not make out any details. Like mine, Oliver’s head was being worked round into the absurd position that people adopt when they are trying to read upside-down matter.

“Such language and such thoughts,” said Mr. Jacobs.

“And to such a family.”

“Which family are you talking about?” asked Oliver.

“And still you persist with this ignorance. Could you not see, before you indulged yourself in this profane way, could you not see that it would bring scandal to this household and destroy us all? Everything I have worked for? Hmm?”

The flipper movement had given way to one of daggers, and the items in his hand were being stabbed closer and closer to Oliver’s face. No longer offensive letters only, but offensive weapons.

Mr. Jacobs was standing where he usually stood, in the centre of the room. To his right was the Bluthner baby grand with its dense colony of family pictures: behind him the acreage of carpet; the power-shouldered suites that I had once seen in the Albany Lounge of the hotel; the Crown Derby china locked behind glass; the heavy pelmets frowning down from the end.

“A family like that,” he repeated.

“It is hardly without influence.”

“But a family like what, father?”

Mr. Jacobs swung round to his right as if he was addressing an invisible new person. On the far side of the broad lawn a grey squirrel scampered over the park wall.

“Ah the ignorance of him. A family like what, father!”

He turned to face us again, and went on: “A family like the one whose daughter you have… defiled.”

I think he meant to say defamed. I think he could also see that we knew, but it would have taken a braver or more foolish 14-year-old than either of us to pull him up on the technicality.

“You never stopped to consider the effects of such a letter?”

Oliver was about to say that of course he hadn’t considered the effects because he still did not know what it said. But the use of forthright denial was doing more harm than good, and so he stood there waiting for the most appropriate expression to find its way onto his face and start marshalling his features.

“If it was only a question of such a family never coming to the hotel again,” said his father, “well then I would have to shrug my shoulders and accept that these things happen. Fair enough, I would say. Many other fish in the sea.”

He was sounding more foreign than usual. He usually did when he was going for the solemn or formal mode. For some reason this increased his vocal range greatly, and he could go from the deep and gutteral to the piping within a couple of words. Oliver and I called it yodelling, and we were never able to keep our laughter contained when it happened. We always had to leave the room or, where that was not possible, pretend we were laughing at something amusing that he had said. There was no scope for that here. The other danger was that he would mix a metaphor, a trait that unfailingly let him down at important moments. Skating on a sticky wicket was a favourite.

“If it was a question not of one but of three or four families like this,” he went on, “then OK. Still OK. Even 20 times, and as many times I would shrug. Oh but what when such a family is a cause of so many banquets, dances and sundry other functions, hmm? And when their friends, and their friends’ friends quote us to each other for bar mitzvahs, weddings and so forth.

Ah well, then I would have to say that such families are sufficiently important to us that we go out of our way to be…to be…yes, gemutlich with them, to be congenital, and that we definitely do not, for example, send to them in the post material of a kind which is likely to portray, shall we say, their teenage daughter as, as…”

As the right word was evading him, he let out a general exhaust of dissapproving air from his mouth as a substitute.

Then he resumed: “I asked, Oliver, if you had stopped to consider the effect of such a letter, but I no longer want to hear the answer. Because the only conclusion I can draw is that you wish to see me ruined. Ruined and humiliated.”

That word again: ruined. He used it at every opportunity, dwelling on it, stretching the vowels away from each other until it sounded like the call of a creature expiring on a barren landscape; a warning to anyone who heard it that they should avoid this place at all costs. I don’t think he had the first idea how awful the noise could sound, and what a feeling of general guilt it could instill into the people who were close to him.

“Perhaps,” he continued, “you wish to ruin and humiliate yourself as well. Perhaps you blame me for your mother. But these things are for Dr. Hardmann, not for a simple man like me.”

Oliver shook his head violently. He was close to tears, although no closer than his father. Knowing Oliver as I did, I could see there was no truth at all in these allegations, whatever they were. I was as confident of this as Mr. Jacobs evidently was in the presumption of his guilt. The other dreadful certainty here was that Oliver had never been in graver trouble than this.

It could only be a matter of time before his father threw in the words “your poor mother.” I was surprised this had not happened already, as he had taken to saying it a great deal in the past few months.

I was about to intervene and say there had been some terrible mistake when he trained his gaze on me. It was more or less the same gaze he had been giving Oliver, but without the proprietorial element that had heightened his contempt. I had only seen him fix his son with that look once before. I have forgotten what the cause of it was, but I think it involved relatives and a bar mitzvah. I can remember thinking that through the awful rage there was something else present - an involuntary pride in the ownership of his son’s sinfulness. Where else did that strange facial current come from? I think it came from the ackowledgement of a bond between Oliver’s incipient manhood and his own. It was a greeting from one to another in this dangerous and fallible condition.

While I was trying to work out what it all meant, I was aware of a compassion arriving in me without warning. I imagined in Mr. Jacobs’ life a great list of petty transgressions, some real, some imagined, some wrongly attributed to him. I imagined him knowing in a private part of his heart that he had, for example, done wrong in building a four-storey extension at the back of the hotel when the council had only granted permission for three. Oliver had overheard people talking in the car park. I imagined him paying money to buy the silence or inertia of important people and then being kept awake by fears that the secrecy would haemorrhage. I guessed he would justify his actions on the grounds of financial security for Oliver’s future. That was generally what he did, and it contributed to his anger. Lastly, I imagined him being tormented by remorse for having broken with his eldest son Lionel over the young man’s decision to take up the offer of a place at the Royal College of Art. The two had not spoken a word since then - no contact at all since Mr. Jacobs’s last observation that painting pictures was for beatniks, queers and layabouts. He had no notion at all of how his disapproval might affect these sensitive sons of his.

Worse, he had no notion of their sensitivity. Since he had been able to do as he had done, survive as he had survived and prosper as he had prospered, it followed that his sons would not only respect his toughness but also display their own.

As he stood there before us, shaking his head from side to side and looking down at the carpet, I found myself thinking of him as a sad and not quite functional baby elephant. This version took the danger from him, and perhaps this was my subconscious aim. His body looked rumpled and baggy in the grey suit that he always wore, and his nose, though big, was no more than a vestigial trunk. It hardly swung at all. Condemned to live vertically on his hind legs, his belly was a sitting target and his arms, no longer load-bearing, could only manage gesture and hasty prayer. It seemed to me this was a terrible burden for a creature, not to be wholly one thing or another.

“Your poor mother,” he said at last. To my alarm the words were not addressed to Oliver, but to me. I must have looked as if this was another mistake because he added at once: “Yes, you young Danny, you.” While I absorbed this fresh news of my involvement somewhere in the scandal, he turned back to Oliver and said: “Yours too, Oliver. Your poor, poor mother.”

So, not one poor mother but two. One of the big differences between Oliver’s mother and mine was that mine was alive and his was dead. She had died of cancer the previous year after such a long battle that it had seemed needlessly brave.

She had proved everything there was to prove about the courage of courage and the inevitability of inevitability. It had gone on for almost as long as I had known Oliver - a cycle of excision and remission, each one as cruel as the other. When friends and clients asked, in the hushed-and-reverend voice reserved for this illness, what she had cancer of, his answer was that it was cancer of everywhere. The last time I had seen her she was so small and grey that I took her to be one of Oliver’s great-aunts who had perished in the camps. A ghost in fact. A tiny white ghost against the crimson of one of the vast settees. She seemed to sense this, and said “It’s all right, Danny, I’m only Oliver’s mother.” In losing her, Mr. Jacobs could hardly have expressed his solidarity more emphatically as he too had lost a vital part of himself.

My father had died in the same week as her, quickly and without warning. A heart attack. Some genetic weakness which means I have often found myself slightly surprised and relieved when I wake up. I had come home one day to find the front room full of people whom I associated with Christmas. They were all wearing dark glasses and talking of their bereavements. These were of no use to me as they all turned out to have occurred thirty or forty years previously. The people smelled wrong to me; over-soaped and scented for the occasion. They kept touching me in ways I found intrusive, and telling me that I would have to look after my mother now that she had no husband to take care of her.

My father had been a music teacher. He was a tremendous natural pianist who seemed to be able to reproduce any tune after a single hearing. But there was some problem with his formal qualifications, which were not good enough for the new headmaster. He was sacked, maybe even accused of deception, and went into a condition which I suppose would now be called a breakdown.

I never knew the meaning of such words back then. A breakdown was for cars that wouldn’t go any more.

A depression was for the weather. No such ignorance now. Barely a scrap of it left.

There were a few private pupils, but they too evaporated. He was the gentlest, most gifted of men, and I was utterly devoted to him. I think I was a surprise to the pair of them, from my birth onwards, and they never repeated it. I do remember a few startled noises from the bedroom, very occasionally, as if she had just discovered a member of the Royal family in the bedroom and he was trying to shush her as the noises would be thought rude. He was kind and warm, and before that inertia took hold of him, very funny in an unassuming way. He went easy on his show of affection for me when she was present, as if he was worried that she would see me as a rival for his attention. She meanwhile would look at me with a rather distant fascination. Either wondering how I’d happened or trying to work out how similar to him I was going to become – liking the notion of me having the good things that he had, but at the same time hoping I wasn’t going to compromise his uniqueness. Once he was gone, and our small house was even quieter and colder, I couldn’t help thinking she was disturbed by my being like him while not being him. I did once think about asking her whether this was the case, and if she wanted me to do something about it, but I couldn’t begin to find the right form of words for such a question.

It was at that time that Oliver and I had become inseparable. Most of the others assumed it was because we were both Jewish, even though that assumption was not true in my case. If Rose is seen as a Jewish name, that is largely because it is the chosen abbreviation of countless Rosenbaums, Rosenthals and Rosenkrantzes. And if we did have a sense of us-and-them, it was because of the deaths.

We became objects of fear, perhaps even of grudging admiration, because we had been touched by unimaginable loss and come through.

I later read that something similar had happened to John Lennon and Paul McCartney. This pitch of experience was not available to death-virgins. If it had only happened to one of us, they might not have felt so excluded, so stuck with their own curiosity. None of this fully explained the victimisation of Oliver, nor the business of the letter. There was only one word that properly accounted for all that, and the word was anti-semitism. There it was, not in all the boys but in a good many of them. It was there in the same way that a particular vowel sound or hair style is there. Just part of the individual. In the majority of them, I’m sure it came down from their parents, one of those automatic legacies that hardly gets discussed. People just assumed it had gone. No-one actually talked about it so it just sort of lapsed. Except that it didn’t. It was there and it was strong. Nice people were in a state that would one day be called denial. The hatred – it was nothing less than that - was powerful; enough in some cases to make the boys brandish it for fear of somehow letting their parents down. I never minded being taken for Jewish; certainly never went out of my way to distance myself from the assumptions, and this must have endeared me to Oliver.

It was after the deaths that he and I had taken to going through the Shades at every opportunity. A lot of this time was spent in silence. But it was a very communicative kind of speechlessness. In fact it was the way in which we could reach one another most directly. Death is such a loud thing in the lives of the young. It deafens you so that the world goes silent and all you can hear is the ringing inside yourself. You can try and talk out from here, but you are not sure you will be heard. So being quiet got more meaning across than words could have carried. Being quiet was language. It’s strange, now that I put it like this, but it was natural at the time. I was quiet at home as well, but it was a different kind of quiet, watchful and unhelpful and all wrapped up in the odd new smells which my mother’s grief hormones were secreting.

Benny Jacobs meanwhile was made loud by his loss; a gong banging itself to draw attention to the injustice of it. This surely was the source fuelling his rage. If only he’d done like others manage to do at such times and railled against God. But Benny Jacobs never managed to put in much time with that one. His Jewishness was more of a civic and catering kind, and in this context it had its own propriety. Its own piety indeed. God was another matter; undoubtedly vital for branding purposes, but so distant, so difficult to talk to. Oliver and I by comparison were very close at hand. Anger was coming down when it should have been going up.

Sometimes, going through the Shades, I think we both expected we might see Mr. Jacobs and my mother in some form, although we never admitted as much. We did speculate on whether Mr. Jacobs and she would start going out with each other. Once, at the hotel’s New Year party, he had asked her to dance, but it was not a success. She was a tall, willowy figure, and with his little elephant head butting up against her bony shoulder, she looked as absent as Miss Tench.

“Your poor mother,” he said again. This time it could have been addressed to either Oliver or me. It passed between us like a tennis ball in a doubles match. The delivery must have been intended for Oliver, because Mr. Jacobs then stood to one side and, with a sweep of his arm like an introduction, indicated the silver-framed photos that stood as thick as a forest on the top of the Bluthner.

Since the deaths, Oliver’s mother and my father had gone in different directions. I mean that all the images of him - the photos and the Seth Rawlings oil portrait - had been removed from the living room of our house and stored in the great Revelation trunk at the foot of the wardrobe upstairs. It was not that my mother was trying to pretend he didn’t exist, just that whenever she saw him she sobbed uncontrollably. She visited him in the trunk from time to time to see the familiar brightness of Seth’s colours, the reassuring black and white of the Welsh holiday photos, and to try and feel the emptiness of his absence. Without being able to say why, I knew this to be of desperate importance.

Oliver’s mother meanwhile had gathered from the farthest corners of their enormous house and now stood in profusion on the piano. Most of the photos showed her in the beautiful maturity of her early middle age, which is when I must first have seen her and been struck by the fineness of her face. But there were others which showed her in her teens, the proud older sister of two brothers. One of these boys had come to England with the kindertransport but disgraced himself in some way and not been spoken of. The other had remained in Berlin and gone the way of so many. With her, jostling for lebensraum, were her numberless great-aunts, cousins and uncategorised relatives whom Mr. Jacobs had lately plucked from their rest between the pages of old albums. There was a cantor called Yasha, a bearded man with shining eyes, and Hannah, and Esther, and others with similar faces and similar names. And downstairs onto the piano they had all come, like children long, long after dark. They surrounded Oliver’s mother and smiled at her. Once, when he was very drunk after a Maccabi Games reception, Mr. Jacobs had gone through their ranks in a macabre roll-call, saying their names and adding the word Treblinka, or Sobibor, or Auschwitz. I don’t think Oliver wanted their presence any more than I wanted my father’s absence. They bore witness to a suffering which would always dwarf anything that anybody else could come up with. And now they were being pressed into service like a Greek chorus, as echoes for Mr. Jacobs’s admonitions.

I looked hard at his face to see if I could detect any signs of too much pill-taking. He had been put on strong sedatives, or anti-depressants, which he referred to as his Chewies. He seemed to have bottles placed strategically all over the house, and the great fear was that sooner or later there was going to be an accident.

The door opened and Oliver’s sister Eleanor came in. She was 19 and on the point of leaving home to work as an interpreter with an Anglo-Austrian travel company called Ausflug. She was a reassuring young woman with a great gift for turning up at the right moment, like now. But reassuring is a bloodless word for her. She was utterly beautiful, although I obviously had to conceal this opinion from Oliver. She had a mane of thick dark hair which she kept threatening to cut, and a jawline that made me certain she would never know the experience of being on a losing side. She always smiled broadly and hugged me whenever she saw me, and I was always surprised by how firm her front felt against mine. Her hair released fragrances which I had never come across before. They were fresh and outdoors but they also had a darker self inside. I lacked any information which might help me decide if it was a bought aroma, a very expensive one probably, or a personal one that came entirely from her.

I placed myself as near to her as I could in the hope that she would throw back her head and release a waft. I had started to blush when I saw her and there was absolutely nothing I could do to prevent it. It was like being punished by a public show of guilt for something I had never done, never even planned. She had been figuring prominently in my most recent wet dreams, and I thought how harsh it was that I had to take responsibility for her appearances there. . The blushes came so fast that they gave me no time to leave the room or cool my face with licked fingers.

Her great project of the moment was to bring about a rapprochement between her father and her brother Lionel. So far it was not going well. Whenever she raised the subject, he swept his arm towards the Bluthner and said “Your poor mother.” This was always an unanswerable move, an ending as sure as dropping the black ball in bar snooker. Game over.

Seeing the clear signs of anger and sadness on her father’s face, she walked over to him, put an arm around his low grey waist and nuzzled against his cheek. It had a calming effect.

“These boys,” he said.

“Good boys, father.”

“No, No.”

“Yes, yes.”

He was about to explain the enormity of our crime when the door opened again and Uncle Maurice came in. He was in a state of agitation. This was often the way at Oliver’s house, each drama being interrupted by the next. On some days there was so much happening, so many comings-and-goings that people could and did mistake it for the hotel.

Uncle Maurice drew Mr. Jacobs aside and whispered something important into his ear. At once he seemed to forget about the documents in his hand and half placed them, half dropped them onto the coffee table. For the moment his interest had been diverted. I felt the sort of relief which I suppose politicians must feel when their scandal is knocked off the front pages by an air disaster.

Uncle Maurice was not an uncle at all, but one of Mr. Jacobs’s oldest and closest friends. He had gained the prefix by a very thorough observance of Lionel’s, Eleanor’s and Oliver’s birthdays. It was a sure subscription to their parents’ esteem. He had stood staunchly by Mr. Jacobs in his bereavement and, as far as I could gather, on a number of occasions going back a good way. He ran a middle-sized construction firm, and was known to be, by a clear head and shoulders, the worst builder in the district. The hotel was easily his biggest customer. Almost single-handedly he had defaced its assorted-period frontage with blind slabs of unweathered brick. Now, at the back, he had put down his most ambitious architectural turd yet in the form of the four-storey extension. Or three-storey.

Uncle Maurice drove an automatic Jaguar, smelled of men’s preparations and had little back-curls like David Niven. He wore the clothes of high-class cads - double-breasted navy jackets with gold buttons, usually over a turtle-necked jumper of manmade fibres. He also did conjuring tricks that involved a cravat and money. I wished he would do one of them now, but there was no chance. I caught a few words of his hurried exchange with Oliver’s father, and these were “miscalculation,” “urgent,” and “liquid cement.” A few seconds later they were off. In the doorway Mr. Jacobs paused to look back at Eleanor. He wanted her to go with them - everyone always wanted Eleanor to go with them - but she indicated with her hands that she was staying with us. Mr. Jacobs did not have time to argue and set off at a surprisingly fast pace, with Uncle Maurice flapping in the slipstream. There was a muted yelp of dachshunds, the heavy thud of the front door followed by the clack of its flapping knocker, and then silence. The carpets felt thicker than usual, and the air hung sombrely above them.

“And this then is the cause of our father’s troubles today?” said Eleanor, picking up the handwritten note and the photographs. “But what on earth is it? Oliver? Danny? What have the pair of you been up to?”

We gave our most honest shrugs and allowed her to peruse the stuff. We probably gave her three seconds reading time before we were on her like foxhounds and tore it from her grasp.

“What are you doing?” she cried.

“We’re in it,” said Oliver.

“I don’t understand.”

I wish I could remember the full text of the letter that we two had allegedly written to Emma Gilberdyke. As I read it at speed, there in the Jacobs’ drawing room, I never imagined I would need to memorise it as it was burning into me so sharply. With some of the feelings that the writer/s expressed, I could sympathise. I agreed one hundred percent that Emma Gilberdyke was “the sexiest girl on the hill, with much better tits than Sandra Wortley.” And I would not have disputed the claim that her backside was “made to be fondled without knickers on.” All this was, as they say, uncontentious, even though I would sooner have died, or been made to French-kiss Miss Tench (a regular dare) than transfer such thoughts to paper with my private stock of images.

The real trouble started a couple of paragraphs later, where Oliver and I were apparently describing in some detail what we would do if we got her in the hotel lift “again” and jammed it on the top floor. To help her imagination we had considerately enclosed a small cutting from a glossy magazine. It showed a woman on all fours astride one man while another was attending to her from behind. I had never seen anything like this and had not, until now, spent any thought wondering if such an arrangement was possible. It did seem to be, but what struck me most about the picture was the matter-of-fact look on all three faces. They might have been buying groceries, or making a call to the operator. For some reason I assumed the magazine was foreign and this was how they did things abroad. It was about the only thing I had got right today. In the corner of the picture was a caption that read: “Monique et ses deux copains.” As Oliver didn’t know what the last word meant, I pretended that I did. “It comes from the same root as copulate,” I said with great assurance, forgetting that Eleanor had fluent French. She laughed, allowing me to think that I had made a joke.

“Our” letter went on in more or less the same way for another couple of pages. At one point the scene shifted from the jammed lift to the poaching wood on the edge of the park. Here, still outnumbering her two to one, we were to put our manhoods (where on earth had we got that word?) into her mouth.

From the accompanying note, the one handwritten in capitals, we learnt that the rude letter had been intercepted or otherwise obtained before it could find its way to the Gilberdykes’ house on the brow of the hill. These photos of the text were merely meant as proof that such a letter existed. It almost sounded as though the writer of the note was doing Mr. Jacobs a favour by drawing his attention to an imminent disaster. But while we could conclude that the letter had not yet reached Emma, there was a snag. It was the sort of snag usually known as blackmail. The note-writer was undertaking to Mr. Jacobs that the letter would not find its way to the Gilberdykes’ house provided that £1,000 in used notes was forwarded at once to a given P. O. Box number. In his shock and outrage Mr. Jacobs must have got stuck on the two linked matters of the obscenity and our certain guilt. He had not been able to move beyond that point and register the more troublesome message of the handwritten note.

As blackmail went, it was of a low type. From Oliver’s and my point of view the author of the scheme had already done terrible damage without giving us the option of buying our way out. Now there was the prospect of more trouble if the money was not paid and the letter found its way to the Gilberdykes’ house. I wondered what Mr. Jacobs would do when he re-focussed his attention on the matter. Would he tell my mother, or would he decide not to for fear of being an unwelcome messenger? What did he think would endear him more to her - benign intervention or laissez-faire? Would he pay the money to staunch the thing, or would he take a moral stand against blackmail?

I looked at the forged signatures at the foot of the rude letter and they looked horribly plausible. As for the typing, that too was familiar, and must have been done on a typewriter like the Remington portable on which Mrs. Jacobs used to rattle out her correspondence. So the forgers must have been familiar with the inside of the Jacobs household. But there were so many people in that category - so many friends, clients, schoolchildren, parents, councillors, hangers-on and virtual strangers that it was impossible to know where to start. And there was no shortage of people who would gladly see the over-prosperous Benny Jacobs stung by public ignominy.

A new fear was falling onto me like a following wave. It sounds implausible now, but it was true then, and I later found out that Oliver had felt it as well. The letter may have been a crude and scarlet forgery, but it had enough substance to engage my guilt. During the next few appalling days there were moments when I found myself caught up in all the emotions that would probably have come my way if I really had sent obscene mail to Emma Gilberdyke. There was the plain shame of the wrongdoing, but there was also the tingle of notoriety at being in the middle of a story with used pound notes and drop-off points, like an episode of Dragnet. While my mind was let loose with the presumption of guilt, it came up with a nasty range of consequences. Pessimism was arriving. If Oliver’s own father was against us, where were we to go for allies? On a purely technical matter, the hotel lift was far too small for Monique et ses deux copains, but I don’t suppose that would have carried much weight in a court of law.

I could see why Mr. Jacobs had made his assumption. Or rather I could understand why his responses had been governed by the fear of offending the Gilberdykes. They lived in Crown Lodge, a few doors down from the hotel, commanding the best view of the river’s famous meander and the shallow barrier of downs twenty miles beyond. Harold Gilberdyke was a prize porker of a man, who always looked on the point of bursting something. If it wasn’t a vein or a valve, then it would be a seam or a collar. Something somewhere had to give. His clothes may have looked big enough in the shop, but once they were on him they found themselves pushed out to breaking point by the sheer outrage that pulsed up from his core. Being one of Mr. Gilberdyke’s shirts would be a terrible life.

He was in taps. That is where he had made his fortune, and many of his taps were in the Mountcrest. Huge numbers could also be found in the three-star bedrooms of the world. He did a De Luxe range called the Poseidon for executive decor specialists, and these tended to be chunky gold castings of reclining sea gods with gushers for mouths. His friends would send cards or even phone to report sightings as far afield as the Alhambra Bermuda or the Halcyon Oslo, much as an actor’s friends might let him know they’d just seen him dubbed into Swedish on an in-flight movie. That at least was a sure way to gladden Mr. Gilberdyke; such a sure way that whenever these friends sensed an explosion they only had to say they had recently showered in Lyons with one of his Nautilla mixers, and he was stilled.

He had started out as a plumber in Leeds and remained proud of his origins. Although he could terrify children with the blood-orange of his face, there was a forthrightness that they responded to. He was not about to apologise for his trade, and he had, in his own words, no side. He had become a pillar of the church and an alderman of the council, and held forth on everything from air noise to dog mess with all the huff and rectitude of a burgher from J. B. Priestley. No-one knew where his outrage came from, although it was plain to see where it went to - just about everything. Declining Standards were the named enemy, but this covered the entire spectrum of natural and human activity; it could include the approach of winter, the arrival of black people in south London, and the balding of his own head. (“Who’s been at me bloody hair I’d like to know.”) It was bracing to see his brand of civic pride trumpeting away in a London suburb. I always liked it when he was round at the Jacobs’ because of his knack of making comfortable people uncomfortable. He had a large sister who repeated everything he said, and a small wife who was never heard to speak.

There was one point on which everyone agreed with him. His best attainment, including the taps, was his daughter. She was everything his own sister - and wife, come to that - could never be. He had had her schooled and tutored and socially prinked in every way known to private means. She could play Scarlatti on the harpsichord, recite de Musset to dinner guests (who were confused by it), make cross-stitch covers for the church kneelers and even fulfil the industrialist parent’s dream by calling him Papa. So one way and another Crown Lodge was not the cleverest destination to choose when sending obscene letters to young girls.

While I was standing there in Oliver’s house, thinking bleak thoughts about the weeks ahead, I forgot that Eleanor was standing just behind us. I caught sight of her profuse hair out of the corner of my eye and found myself wishing once more that I was several years older and engaged to her. Several years older but still the Danny whom she knew through her little brother. There would be no need for prolonged courtship because we could both just build on the existing friendship. Oliver might be jealous to begin with, but he would be delighted to have me as his brother-in-law. There would be a great wedding - at the hotel of course. Lionel would come, a healing between him and his father would begin, and I would gain Eleanor’s everlasting gratitude. We would buy a mews house in the Hill Village and keep a kindly eye on him as he moved into old age.

Not even Eleanor, intuitive as she was, could guess what was going through my head. Maybe she could feel the presence of the guilt because she took the mischievous documents and threw them dismissively onto the coffee table. They slid along the glass top and tumbled off the far edge. As a little scatter of paper on the carpet, they looked innocent and inconsequential. Then she put one arm round her brother, the other round her fiance manque, and said: “Don’t worry, boys. Everything will be all right.” For the first time since I had met her, I knew that she was getting it badly wrong.

Chapter 2

Deerleap House stood at the top of our cul-de-sac, overlooking the park. This was Seth and Ruby’s thin, weird home. Because of all the old stories about people coming out different than they went in, it had some peculiar hold over the local imagination. If there was such a thing. To me it was the most natural, comforting place in the world, and I came here whenever things were bad, as they were now. It was away from the smart houses and the big view. Close to the little footgate leading into the expanses of the park, where you could really breathe. Since the deaths I must have spent almost as much time at Deerleap as at the Jacobs’s. During the empty days of the school holidays I would shuttle between these homes, half a mile apart. I would also make sure I spent a proper amount of time at our own house, waiting for my mother to return to life. It was like watching a freeze that is hanging on and postponing the spring. Once, when I saw her asleep, her face had the blank serenity of a perished mountaineer looking out through a layer of ice.

Today all my energies were channelled into putting the Emma Gilberdyke business from my mind. It wouldn’t go. What if the threat was carried out and the letter with our forged signatures was sent to the Gilberdykes’ house? What if Emma’s father took it on himself to tell my mother? The questions came on and on and my mind was running itself ragged in pursuit of answers. I would hang for the obscenity. I would make a false confession and so exonerate Oliver and win his sister’s heart. But it would be too late. She would arrive at the execution site, which for some reason was in the front drive of the hotel, only to see my body swinging limply before the lenses of the national press.

At Seth and Ruby’s I would be all right again. Everything was always all right, even if only for the moment, in the embrace of Deerleap House. And they were always in, which was part of the security of the place. The building had tiny rooms which had been pushed back into themselves by the unreasonable demands of the staircase. It had more front windows than any other building in the street. It was an advent calendar of a house. The flaps and shutters opened to reveal a cat, a very old woman, Ruby’s Rapunzel hair or Seth working at his easel. It was an array of little tableaux that somehow joined up inside and drew animation from a common source within. It was like a model and yet it was as tall as the park trees whose boughs would dip over the wall under the weight of the squirrels.

The very old woman was Ruby’s mother, Ma’am. Her great age regularly pulled her face into a scream-like expression of astonishment. Because of certain episodes - two in particular - she was thought to be immortal. The first involved being taken away in the council dustcart and tipped out in the depot at Rivermead. A worker got suspicious when a flattened pile of refuse began stirring with human limbs. The second involved falling from the house in a full bath when the floor gave way. Neither episode caused her a scratch.

She was truly small now, as small as a child, and she was often being stumbled on in corners and baskets meant for animals. I suppose she was suffering from senility, but this was not apparent all the time. It was a condition she had visited for years, returning from it just when she seemed to have taken up permanent residence there. On bad days her little legs were as much use as a wishbone. On good ones she could still get about by supporting herself with her fists on the lower reaches of furniture. She was like a creature walking on its knuckles.

When she was on one of the upper floors she would often call out to passers-by to see if they could spot her. Seth would carry her up and down whenever she asked, and no household pet on its last legs was better loved and cared for than Ma’am.

There was one aspect of her that worried me. She had once told me I should have nothing to do with Oliver or his family, and that no good would come of it. Those were her very words: no good will come of it. Delivered like something out of a pre-war rep drama, but no less chilling because of that. If she had been one of those self-styled Cassandras, the sort who tell you they are a witch in order to brighten a dull character, it wouldn’t have mattered. But she was not one of those. I couldn’t even ask her for her reasons because she just moved away on her knuckles and that was the end of it. I kept meaning to ask Seth and Ruby about it, but then flunked it in case I got the wrong answer. Knowing what I later learnt, my caution was in order. I did wonder if there had been some old slight, going back years, but I couldn’t imagine what it might be. Even though the houses were only ten minutes apart, the people in them inhabited two utterly different worlds. So different that the only common point was surely me. At least, that’s how it looked at the time.

As I drew level with Deerleap House, I could see the side of Ma’am’s face in one of the top windows. Seth’s old shooting brake was parked beside the kerb. This was also so old now that it was starting to get strange looks from other motorists. I don’t know if it was a Countryman or a Vanguard, or something that Seth had put together himself. The woodwork beneath the windows had decomposed so much that it was as porous as soil and was hosting a variety of lichens and mosses. There had been some compact blooms that rioted in the spring and turned the narrow strip into a bright little window box. By autumn the vehicle was giving off its smell of mulch and old leather. It was in hibernation now and the woodwork was as lifeless as the ground.

Ma’am’s face vanished from the top window, and a few seconds later Seth appeared at the front door. He had a soft round face with a goatee that was not so much a beard as a failure to shave. In the days when his hair had been thick and fair, like a Viking’s, the beard had looked very sparse. But since the hair had become full of gaps, the beard had drawn encouragement and thickened up, and now the two could have changed places without anyone knowing. He was wearing the only clothes I ever saw him wear - old chef’s trousers with black and white squares, and a blue sailing smock that would have been the death of Cowes Week. The smell of his pipe came forward like a person. It was a sweet mix of Balkan Sobranie and something else, and it carried the memory of my father so powerfully that I could almost see him forming in the shapes of the smoke. I wondered why my mother would not go up to Seth and Ruby’s, and she later told me that the pipe smoke reminded her too strongly of my father. I believed her, I suppose. The two men used to use the same mix, and ran supplies to each other if one of them had run out.

Seth welcomed me in, and indicated with his pipe that Ruby was downstairs. He looked as if he had been expecting someone other than me, but was relieved that I had turned out not to be this other person. He was distracted, and his eyes flicked over my shoulder to check that I was alone. It took him a few seconds to settle into his usual composure. Something had been troubling him; something beyond the routine strain of keeping the three of them on an income as small as they all said it was.

It was impossible to get to Ruby without first seeing countless images of her. They were on every part of every wall. There would have been no point in re-papering, as 95 per cent of the labour would have gone unappreciated. Here was Ruby young, Ruby less young, Ruby now, Ruby clothed, Ruby not so clothed, Ruby not clothed at all. Through all the varieties of age and presentation there was a constant in the still, steady focus of the eyes. They were all the cliched things that terrific eyes are said to be, like limpid, dark, liquid and so on. But those are other people’s adjectives, for other eyes. It was that focus which made them unique, and although I could not say why this was so, the reason was staring me in the face. Or rather, it was staring her in the face and she was staring it back at him. That is why the look was incomparable. It was for him, Seth, and in the intensity with which she gave it, it could never be for anyone else. Yet even if you only picked up a faint visual echo of that intensity, it was still enough to make you feel you were being looked at with the utmost commitment. It was reflected heat, but it still burned hard. Sometimes the strength of it disturbed me and made me fear I was intruding on a private transaction.

This feeling was as strong in its own way as the sense of trespassing which I sometimes felt towards Benny Jacobs when I was over in the other world of that plushed-in household. Yet the function of a picture was to be looked at. Withhold scrutiny from it and you diminish its purpose. Years later I was trying to describe this sense of intruding into the painting of Ruby to a composer friend, and he said but of course, that’s exactly what I had been doing, and that was the point and power of art; it robbed the onlooker of his passive function and made him take part in a transaction.

I followed Seth down the stairs, past the Rubys. There were some with bursts of colour that shone out as brightly as my father in the Revelation suitcase. There were some as rounded as Rubens and others as spindly as Giacometti. Of course Ruby did not change shape as dramatically as this in her own life; it was just Seth processing the image in different styles. One picture consisted of a few lines in charcoal. Next to it was an oil, painted with such a loaded brush that the strokes stood up in relief, each one edged by drops or ridges. To walk down this flight was to see a single face passed through an unguessable prism.

Ruby was in the kitchen, tending to the great jars. There was a fug as thick as wool. The winter sun slanted in through the little window and created a leaning column of light. It looked solid enough to be a flying buttress. On the floor this same light fell like a square of gouache. Ruby’s cigarette smoke made fresh traces in the Sobranie fog. The room smelled of staleness, but it was fresh staleness, shot through with spices, acrylics and Swarfega. She was ageing away from the early and middle paintings. When she noticed me in the doorway she came straight over and aimed a loud kiss at my cheek, only just remembering to take the cigarette from her mouth in time.

“Danny Rose, where have you been?” She sounded more Indian than usual today.

“I’ve come down from…” I began, and then quickly checked myself before saying “Oliver’s.” Ma’am had almost certainly passed her disapproval of the Jacobs family to her daughter. “I’ve just come up from home.”

“Your mother now Danny,” she said. “You must look after your mother.”

I resented it when people told me this, as they kept doing. I didn’t know how to look after myself, let alone someone else. I had got the same instruction from my cousin Richard after the funeral. He shook my hand, left a pound note in it, and said “Good luck old man and look after your mother.” Then he went back to Canada, where he had joined an engineering firm. I never knew if the pound was meant to take care of her, or for how long, or if I could use it for the cinema.

“Tell her to come here, Danny,” said Ruby. “We’ll look after her.” Once again I couldn’t work out if this was meant to be a permanent arrangement. I was still finding it very difficult to tell what adults really meant.

“Won’t we, Seth darling?”

“Hmmm?” said Seth, who was standing behind me in the kitchen doorway. “Hmmm? Oh yes. Of course.”

“She’s so near,” Ruby continued. “She should come up.”