7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

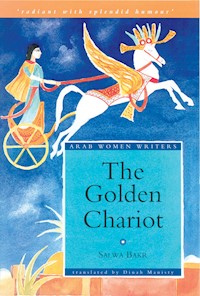

From her prison cell in Cairo, Aziza decides to create a golden chariot to take her and fellow prisoners to heaven, where their dreams can be fulfilled. Aziza's narrative holds together the stories of the other women and their crimes as they yearn for a better life, but cannot realize these dreams.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The Golden Chariot

by Salwa Bakr

translated by Dinah Manisty

The right of Salwa Bakr and Dinah Manisty to be identified respectively as the author and translator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Contents

Introduction

Translator’s Note

1 Where the River Flows into the Sea

2 The Heart of the Matter: the Meeting of Opposites

3 The Cow Goddess Hathur

4 An Escape to Better Things in the Golden Chariot

5 Mercy before Justice

6 There Once Lived a Queen Called Zenobia

7 Grief of the Sparrows

8 Melody of the Heavenly Ascent

Introduction

Set within the walls of a women’s prison just outside Cairo between the 1950s and 1970s, The Golden Chariot introduces us to Aziza, a member of the Alexandrian aristocracy now imprisoned for murder. She presents an intricate woven frame narrative, within which we become acquainted with the other fourteen inmates and the prison warden. The novel takes place in a women’s prison as an ‘allegory or metaphor’1 for the social reality outside the walls and as a reaction to dishonesty, oppression, violence, economic deprivation and social injustice. The women have committed crimes ranging from pickpocketing, begging and prostitution, drug dealing and murder, though some women like Umm al-Khayer and Aidah are in prison for the crimes of others.

The main reason for their crimes is the abuse of their bodies by men, where the body emerges as a contested space. Many commit crimes as a reaction to men abusing their bodies, men being unfaithful, dishonest, exploitative and violent. Most of the crimes are as a direct result of ‘the violation suffered by them at the hands of men’.2 Aziza’s body is violated by her lover, her step-father, which leads her to kill him. Hinnah kills her oversexed husband, Azimah castrates her lover who enjoyed her body for years but refused to marry her.

Yet the prison is also a haven. Salwa Bakr creates a space in a women’s prison outside the traditional private and public spaces. The imposed roles of daughters, wives and mothers subservient to fathers, husbands and sons have no relevance here. The women prisoners get rid of the masks that a patriarchal society imposes on them.

The novel was conceived in Egypt in the mid-1980s when the daily newspapers began to cover women’s crime extensively. The rise of female crime, or coverage of criminal women, caused a controversy over the causes and implications of the ‘gentler sex’ resorting to violence against men. In both criminological and lay explanations criminal women were seen as either inherently evil, becoming more masculine, committing crimes because of their increasing social freedom, or committing crimes as a result of simply going mad.

The author, with a mischievous grin on her face, sets out to destroy all these dominant myths and expose their crudeness. She uses parody, irony, satire and stories within stories, constantly negating her narrative in order to challenge the reader’s ready-made ideas about women and their position in society. For this reason the theme of madness runs throughout the novel – due to her slight madness Aziza is kept in solitary confinement, Aidah refuses to talk as a protest against the injustice of the world, Shafiqa becomes completely paralysed with grief, while Bahijah suffers from the schizophrenia of a society which at one level affords her the respect due to a woman doctor but then denies her a husband because of her poverty.

This deliberate selection of characters who suffer from neurosis, madness or odd behaviour questions the dominant system that labels them. Through these inmates, doubly confined by imprisonment and madness, the writer presents an alternative discourse aiming at carving a space for women in what Sabri Hafiz calls ‘the dominant discourse of power, exclusivity and superiority’.3 Bakr uses her imagination and powers of story-telling to examine the monological central discourse. She questions the borders between madness and sanity; normality and abnormality and undermines them as fossilized concepts within the bounds of a patriarchal society. No final answer to the complex question of women’s criminal behaviour is offered. I have chosen this novel precisely because it gives a unique insight into the world of Arab women prisoners but discourages the reader from either condemning or sympathising with them.

In a mode similar to Scheherazade in the Arabian Nights, Aziza’s narratives provide the novel with a structural unity. Her telling and retelling of the stories of the inmates weaves seemingly disconnected episodes together and gives voice to ‘a vocal, knowledgeable narrator intervening to pass judgements on the characters, unify episodes, narrate and tell stories, comment and clarify, and connect the world outside to that of inside the prison’.4 Using Aziza as a mask which she chooses to wear at times and discard at others, the omniscient narrator moves within the text creating the tension that is the core of the novel, that is the conflict between the stories of the women and Aziza’s narrative. It is here that the social commentary of the novel lies.

Aziza is a member of the upper class and most of her initial encounters with the women prisoners show that Aziza is repulsed by their physical appearance and condemns them as deviants from the social norms. This is in accordance with Lombroso’s theory of criminality, her observations show that she believes that the inmates’ socio-sexual destiny is dictated by their ‘biological attributes’.5 However, as she becomes more acquainted with their stories, Aziza begins to question her initial reactions to them, which leads her to question her background, education (or lack of it) and predetermined ideas. The women gradually become other than what their ‘evil nature’, ‘madness’ and ‘ugliness’ suggest. A re-examination of the moral values of a society which condemns her as a killer of her incestuous step-father and condemns other inmates as criminals and deviants takes place. Gradually the women prisoners are freed from the reductionist and essentializing biological and psychological explanations for their criminality. Perhaps the main precondition for their lawbreaking is, as Pat Carlen would have it, their ‘consciousness of economic marginalization’.6

Language and the part that it plays in the marginalization of women within a patriarchal structure is another theme picked up by this novel and others in the series. In the past Arab women writers used correct standard Arabic language, Fusha, which is similar to the language of the Qur’an to prove their linguistic credentials to puritan Arabists. The Arab Women Writers series shows a clear departure from the use of standard Arabic. Women writers in this series use a colloquialized Fusha to describe the daily experiences of women. The dominant written Arabic was found inadequate to present their sexual, religious and social experiences. To be true to the women’s voices the oral tradition had to be brought in. The Golden Chariot draws strongly on a rich oral tradition, the voices of the women, which most of the time cannot be distinguished from each other, are close to colloquial Egyptian.

Bakr’s awareness of the Arabian Nights, the Qur’an and a long tradition of folk-tales is evident throughout the novel. She uses digression to provide social and political commentary, long sentences to construct a tableau made up of numerous tiny details, and tales within tales. ‘Her style is similar to the style of folk-tales (al-haki al-sha’bi) which depends on digression, description, accumulation of seemingly separate details, and turning dramatic events into narrative.’7 The author intervenes to punctuate the text, open it up to bring in the wider social picture and stop the text sliding towards the melodramatic. Women create a different language where the patriarch is lampooned, ridiculed and where women’s oral culture and daily experiences are placed at the centre of the discourse. The standard perceptions of masculine and feminine language are rejected and from a third space within the language they question a culture which misrepresents their experiences.

The Golden Chariot is an exercise in the suspension and questioning of preconceived ideas. Whenever the reader moves closer to identifying with the inmates, another possible interpretation is presented in the text. Satire is used to distance the reader and prevent identification with or condemnation of the characters. The text is continually deromanticised, the normal becomes the abnormal and the periphery is pushed to the centre. In an attempt to subvert the symbols of romantic love Aziza wishes that she were able to find more romantic ways of killing her lover, like covering him with melting chocolate or suffocating him with the smell of flowers.

The narrator, through Aziza, then provides the women with a fantastic way out of their misery in the shape of a golden chariot which will fly the women prisoners to heaven where their crimes will no longer matter. Aziza organizes a farewell party for the inmates similar to public feasts or festivals. Bakr, by using this fantastic journey, shows that an escape route exists and instigates an alternative world.’ On the space of the white sheet, I construct my chosen religion, my personal moral values, the politics I aspire to, my favourite world; I become free, really free, away from the romanticised past and the nightmarish present.’8 But in order to stop the reader from taking this heavenly journey seriously, the author negates the whole project in her choice of title for the Arabic original, The Golden Chariot Does Not Ascend to Heaven. The narrative continually dismantles itself in order to keep the reader vigilant and alert. The writer, having the last laugh, walks away from the public festival she creates.

Dinah Manisty’s knowledge of colloquial Egyptian made it possible for her to preserve the local colours in the translation. Her years spent studying Egyptian women writers in Egypt meant that she is perfectly suited to this translation, which depends heavily on detailed and colloquial story-telling. In the absence of many good translators from Arabic into English, a problem partly responsible for the absence of Arab culture from the international arena, her efforts stand out.

It was partially to redress this lack of intervention of Arab culture that the Arab Women Writers series was started. Arab women are treated as a minority in most Arab countries. They feel invisible, misrepresented and reduced, often perceived as second-rate citizens. They are thus subjected to a peculiar kind of internal Orientalism and hidden behind a double-layered veil. This series aspires to open a window on the walled garden where Arab women’s alternative stories are being told, to challenge the foundations of a patriarchal tribal system. It also defies Western preconceptions about Arab women, lifting the veil to show the reader the variant, colourful and resilient writings of Arab women and so that the clear voices of Arab women singing their survival might be heard.

Fadia Faqir Durham, 19951 Itidal Uthman ‘Habs al-Rajul fi Ghurfat al-Zuhur’, al-Katiba magazine, no 7, June/July, 1994, p6.2 Dinah Manisty’s unpublished thesis ‘Changing Limitations: A Study of the Women’s Novel in Egypt (1960–1991)’, SOAS, 1993.3 Sabri Hafiz ‘Layali Shahrazad wa-Layali Shahrayar’, al-Katiba magazine, no 7, June/July, 1994, p6.4 Latifah al-Zayyat, ‘Qira’ah fi-Riwayat Salwa Bakr al-‘Arabah al-Dhahabiyyah al-Tas’ad ila Sama’, Fusul, vol 2, no. 1, Spring 1992, p275.5 Pat Carlen, Criminal Women: Autobiographical Accounts, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1985, p2.6 Ibid, pp 9–10.7 Latifah al-Zayyat, ‘Qira’ah fi-Riwayat Salwa Bakr al-‘Arabah al-Dhahabiyyah la Tas‘ad ila al-Sama’, Fusul, vol 2, no 1, Spring 1992, p276.8 From In the House of Silence: Conditions of Arab Women’s Narrative, Fadia Faqir, ed., a collection of testimonies by Arab women novelists to be published by Garnet Publishing to complement this series.

Translator’s Note

This novel uses colloquial Arabic to capture the reality of the spoken language for women in Egypt. When transliterating Arabic names and words into English, I have reflected the local pronunciation wherever possible. Thus the traditional Arabic name Rajab has been written as Ragab, following Egyptian phonetics. Umm Ragab means mother of Ragab. The only exception is the word Hajja, a title used for a woman who has undertaken the pilgrimage to Mecca, and now commonly used as a form of address for elderly women. This title is used throughout the Islamic world, and I have retained the standard transliteration.

I would like to express my warm thanks to Mukhtar Kraïem of the Arabic Department, Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, University of Tunis, for the valuable advice and support he gave me while translating this novel.

1 Where the River Flows into the Sea

Aziza the Alexandrian woke from her usual midday nap which she took to make up for the long hours she was up during the night, sometimes till dawn. The din of daily life in the women’s prison had subsided a little; the laughter mixed with the sound of crying, the habitual quarrels between the inmates over the bathroom, the fights over food and the perpetual shrieks of rebuke from the warders demanding submission to the rules and regulations which governed prison life.

Stretched out on her bed on the floor, she opened her eyes. Through the open window high up in the cell, her gaze rested on the wispy outlines of the trees, now slightly blurred in the fading light. She listened for a few moments to the evening chorus of sparrows which settled on the branches, bidding farewell until the dawn of another day. It was a performance she had listened to at the same time every evening since the first day she came to the prison. The chirping and twittering usually blended with the voices of Sheikh Abdel Baset or Mohamed Rifaat chanting beautiful Qur’anic recitations. It was Hajja Umm Abdel-Aziz who tuned in the radio to the station which broadcast the Qur’an and placed it on the window ledge of the special block for elderly and disabled prisoners.

Aziza gave a deep sigh when the Sheikh came to the comforting words of the Wise and Almighty: “For you who are punished there is life, O most wise!” She had begun to feel anxious and breathless; the intense humidity of August, which ripened the cotton until it burst open and which made the dates plump and full also brought with it the oppressive weather which dampened her spirit. Sweat smelling of rancid dates trickled down from her neck and from under her arms. She got up and took off her regulation long, prison robe made from white calico and walked across the room. She cupped some water in her hands from the green, plastic bucket in the corner and splashed her face and neck with it. Then she washed under her arms, letting a few drops fall into an old al-Mizan ghee can, which was now used for scraps.

She wiped her wet hands over her hair to gather the soft strands which had strayed during sleep from her bun secured with nets and pins. When she had finished she began to walk a little in the big room. One of the windows looked onto the long corridor which led to her cell, and the others, in this block of the prison reserved for disabled, sick and ‘special’ cases. She tired of walking and went over to the other window, hoping to cool down and lift her spirits with a breath of fresh air; the cold water she had washed herself with had long since dried. All she could see was the high wall topped by barbed wire which separated the women’s prison from the men’s and a few treetops which were slowly sinking into the darkness. She sighed with irritation and left the window with its thin, iron bars and the bleak outlook which had become engraved on her mind since they had moved her to this cell. She went back to her bed and sat down to begin the solitary evening ritual – which she had followed for many years, where she withdrew into herself and ruminated over her grief and the memories of days past. This was the time she allowed herself to communicate with her lonely soul to relieve it of its pain and torment and shattered hopes.

Aziza lit up a Cleopatra cigarette and inhaled deeply with the pleasure of a heavy smoker, hooked since youth. She gazed at the scattered stars looking down on her from the small chink of clear sky which she could see through the window. She poured a little cold water into the plastic cup resting near the earthenware pitcher and took a sip. As part of her evening ritual she summoned up Umm Ragab, in her imagination, from her bed in the next door block. Then, sitting opposite her, she spoke her mind, in a low voice, about how her neighbour carried on: “Listen, Umm Ragab; your trouble is that you’re a donkey. The first day I set eyes on you I said to myself: ‘This old woman, with her coarse, red, dyed hair must be a silly ass.’ When I first saw you I reckoned you must be well over sixty and you’d have to be an ass to land up in prison at that age. When Mahrousa, the warder, told me what you’d gone down for, I said: ‘This old woman must be a fool’, because, Umm Ragab, you’re in for something so trivial. Three years for stealing a wallet nobody would look twice at with a measly ninety pounds in it – that’s thirty pounds for each year of your life in prison. The odd thing is how you owned up, at the investigation, to having been a pickpocket all your life – you said you ‘stole to put the flesh on your bones’ – and what’s more, you’re stupid enough to go and tell them how you did it.”

As usual, Aziza imagined Umm Ragab sitting in front of her, in the flesh, weeping and trembling as she heard these rebukes; she watched her thin lips, framed by fine folds of skin, which creased up as her small mouth twitched nervously. But Aziza knew that these rebukes were only the outward cause of Umm Ragab’s tears; the real cause was the sorrow she felt at not having been able to bid her daughter farewell at her graveside. Moved by such suffering Aziza tried to calm the grieving mother, keeping her image before her in the solitary cell despite the racket coming from next door. Umm Ragab’s snoring, which hissed like the escaping vapours of a steam engine, was at that very moment rising to a crescendo and reached Aziza’s ears clearly through the open windows. It was hard to believe that this exhausted old woman, sapped of strength by a heart attack that had nearly killed her only hours ago, was sleeping so soundly. It was thanks to Hajja Umm Abdel-Aziz, who gave her heart pills quickly and remained by her side caring for her until the crisis was safely past, that she had survived.

Aziza filled her cup with water; she raised it as if to offer Umm Ragab a drink to stop her crying and calm her down a little. “Enough. Stop weeping, because all these tears, day after day, are taking their toll. Think of yourself for the sake of your poor grandchildren. They’re waiting for the day you get out so that you can smother them with your love. You have many hurdles to clear before they’re grown up and can fend for themselves and face the world.”

Aziza knew very well that nothing would lift the burden of Umm Ragab’s sorrow despite her attempts to console her. But she tried to stop her weeping and wailing because she felt her misfortune had no limits. Her only daughter had been widowed a few months before her mother went to prison and then she died, leaving three orphaned children behind, the eldest of whom was only ten. All attempts to save her had failed when the flame of a kerosene stove had caught her long, nylon nightdress which flared up, sticking to her body and turning her into a black, charred lump.

Despite her skinny body and weak heart – which according to the prison doctors threatened to stop at any minute – Umm Ragab never stopped arguing and picking fights with everyone around her. However, since Aziza had learned about her tragedy, she had softened her manner towards her and no longer thought that she was just a wicked old woman. She needed an operation to change two valves in her heart which would, of course, never happen because there was no way Umm Ragab could afford the huge amount needed for a specialist operation of this kind; as for the government hospitals, the queues of those waiting for such operations overflowed into the street.

Aziza put the cup on the floor, tired of holding it up without any response from Umm Ragab. She stubbed out her cigarette butt, and screwed up her eyes a little to examine the woman she still imagined seated in front of her. “I have a surprise for you, Umm Ragab,” she said. “A surprise which will make you very happy. But as long as you go on wailing, I’ll keep the secret to myself. It’s up to you. Wail as much as you like; God willing you’ll burst and then you’ll only have yourself to blame.”

Aziza’s face broke into a broad smile revealing her teeth which used to be pearly-white but were now filthy, blackened through neglect and continual smoking. She was revelling in her ability to use her secret as a threat to try and stop Umm Ragab crying and soothe her own tormented soul. So she raised the cup of water and gulped it down as if it were a delicious, mature wine instead of water from the pitcher. She always took care to fill the pitcher before the cell door was locked behind her in order to make sure she had enough water for the whole night as well as the next morning. She surrendered herself to the delicious stupor which filled her head – a head which still retained traces of a lost beauty – to summon the illusion of drunkenness from that beautiful life she had led in the past, which obsessed her still. She lit herself another cigarette and gazed at the rings of blue smoke rising before her, with the same sad, deep thoughts which often filled her consciousness as she remained alone in her cell, taking her far, far away to her old world, now hidden by bars and walls and long years – long years of solitude in this terrible cell where she sat, longing for the smell of the sea and the distant sound of roaring waves, which she had often heard in her old house. Her spirit yearned to be back in Alexandria, her city, whose architecture had carved vivid reliefs on the walls of her memory.

Aziza the Alexandrian first entered the world of the women’s prison before she reached the age of forty, sentenced to life for killing her stepfather, without any reason that the court could ascertain. She insisted on repeating the same statement to explain how she murdered him: as he was sleeping in his bed one night, she slid a sharp kitchen knife into his chest. She claimed that it wasn’t he she killed but someone else she found sleeping in his bed. Despite all attempts by the authorities to make her talk and to extract some other statement from her which could mitigate her sentence, she insisted on giving them all the details of how she inserted the knife into the merciless heart of he who had torn her own heart and broken it. She burnt her beautiful memories with him and disposed of all her precious belongings, giving them to a charity for the lepers who begged in the streets of the city and were so obviously in need of care. Then after she killed him and was certain that he had breathed his last breath, she set fire to his photographs and those they shared, to his papers and clothes and to the precious wooden cane with the ivory handle which he used to carry so stylishly. She also set fire to everything else in the beautiful old house with the large, lush garden, which had played host to the lovers, to each moment of their passion and was full of wonderful memories.

Aziza continued to mull over her memories even as she sat in prison – memories which never made her regret what she did because she only killed for the sake of preserving these beautiful, unblemished memories, sweet and pure. The person she killed was not the man she knew so well, who had protected her and raised her from innocent girlhood to the perfectly formed beauty of womanhood. The man she killed was another, with the same features and form as him but without the heart and soul which she had loved with such passion for so long. She was convinced that the man she killed, that other man in his image, who violated her beautiful body before she was even thirteen, was a dangerous criminal who had stolen her loving heart and wasted the passion she poured out for the sake of her love. The man she loved turned out to be a demon in disguise who suddenly revealed himself to her, destroying her happiness and shattering the edifice of tenderness in that old house.

Before the murder she dreamt up many original ways to kill him in a manner befitting the original man she had loved for so long. It was inconceivable that she could kill such a beautiful and noble man in a base, brutish and unseemly way. One time she thought of drugging him heavily so that he couldn’t move, then coating him with vast quantities of boiling dark-coloured chocolate until it hardened into an enormous mould of sweetness which no one would be able to resist. She decided to decorate it with dried cherries, sesame and mouthwatering whipped cream. It would then be cut into small pieces with a pick and knife and arranged delicately and tastefully in an amazing spectacle on blue and gold-rimmed sweet trays made from Chinese porcelain. While most of it would be distributed to neighbours and friends, the piece containing that wicked heart, which had once tortured her and left her helpless and despairing of life, would be reserved for herself.

Another time she thought up an alternative way of killing him which might be more suitable. It crystallized in her mind after all those nights spent thinking on her own in the big house, which had become desolate and melancholy – haunted – since her mother died. As she sat on the sofa below her bedroom window gazing at the moon, she could hear only the rustling of the trees and a plaintive sound within her. It was then that she decided to kill him because he was determined to marry that other woman, whom he had begun to love instead of her, and on whom he decided to bestow his new heart. She never believed it was the same heart which had loved her for so many years, from the time she was a little girl, still ignorant of sensations of adult desire. The only method she could think up which fitted her plan to destroy him nobly, was to drug him heavily before he went to sleep and then to bring a huge quantity of rare and beautiful flowers, carefully picked on the morning of the appointed day for the murder. These would be purchased from the best flower shop in the city called “Beautiful Memory” – the very shop from which her lover had bought her violets, narcissi or jasmine during that time of fiery passion which she thought would never end. She would form an arrangement to match his taste in flowers, using white jasmine, birds of paradise with their fan-like veins and magnificent colours in the centre, lavender of mourning and roses from the countryside which she loved, blood red or canary yellow or the colour of his beautiful cheeks which she often used to kiss. She would use her skill in arranging flowers to place them all over him, his head, chest and legs until his body – lying motionless and prostrate after the drug she had administered to him – was completely covered and smothered by their fragrance. Then after she had made completely sure of locking the window and door of the room, letting only the minimum amount of air in, she would leave him to die a slow and beautiful death while he inhaled the lethal fragrance, that familiar scent which she remembered from the beautiful flowers he had given her in the past.

However, Aziza did not use any of the inventive plans she had hatched for a beautiful and truly original murder. She dreaded the scandal that would follow if her secret were found out and her newly created death plan failed, either through lack of precision in its execution or the untimely discovery of her intentions. So she decided to use the knife since it was the quickest and surest way of achieving what she wanted, and gave her the element of surprise which she herself had experienced that day in the distant past when she was still a little girl with pigtails, a little girl whose childhood fate had snatched from her. Like most women she was destined to be a housewife managing the affairs of her narrow world, within the boundaries of four walls, cooking, cleaning and supervising everything to do with the home-bound life which characterizes a woman’s existence. On that distant day when her childhood was stolen from her – a day which would never fade from her memory – she was standing in the kitchen preparing dinner for the little family of three made up of herself, her stepfather and her mother, who had just left the house to mourn with some neighbours. While her mother lamented and grieved with the family who had tragically lost their little son, inadvertently swallowed up by the sea, her daughter was pumping the kerosene stove with all her might to try and ignite the flame under the copper pan full of pieces of reddish unripe taroplant, when her stepfather called her. Having returned from work in the afternoon he was sitting on the Istanbuli chair, resting his hand on the arm upholstered with fine English fabric, when he called her to come and take off his shoes, as she usually did. She hurried in from the kitchen and, as she was busy undoing the laces of his soft leather shoes, he suddenly lifted her onto his lap and kissed her over and over again. After a while she realized that his kisses were different from those he used to give her on her cheek – new sensations overwhelmed her little body which should never have experienced such feelings so young – the little body which had not yet ventured beyond the world of innocence.

Since those distant moments, deep in her early childhood, that old man always remained strong, beautiful and fascinating in her mind – even after she slid the kitchen knife into his chest. He was capable of influencing men and women alike and arousing strong emotions, as well as something mysterious akin to fear and awe. Aziza often noticed this effect he had over others from observing all those who had dealings with him, men and especially women, whether at home or when they were out.

On the day of the taroplant incident he told her, while she was still on his lap, that he loved her deeply because she was young and beautiful like one of those mermaids who only appear at night, secretly. Then he asked her to love him just as he loved her and to obey him. He got what he wanted: Aziza continued to obey him as if she were bewitched, her obedience sustained by her infatuation and the compulsive fascination she felt for him. Since those moments in the past, which took place all those years ago but which still remained fresh in her memory even up to the moment she murdered him, she had loved this man passionately, faithfully and wholeheartedly in a way which would be difficult to match. Indeed it was a love so bountiful that it could be divided amongst a thousand women who were devoted in their love. She gave herself, body and soul, because she considered this lover, who had taken her by surprise, no less than an idol, a worshipped god, whose every command must be obeyed, the only person she could ever love. In this way, during those long years, she called him her “worshipped man” which was a secret name only the two of them shared. He was a man who possessed two women, connected to each other through the mother’s womb. The three of them lived in that large old house which her mother inherited from Aziza’s real father, now dead, and their secret love remained wellguarded and sacrosanct. The mother never knew about it, nor felt the fiery passion between her husband and daughter. She never noticed those impassioned looks and the burning sighs emanating from the depths of the heart and all the drunken kisses in which the lips melted, nor the heated bodily caresses which were deafening in their silence. This ignorance and unawareness was not through lack of sensitivity but because that happy gentle mother, who never for a moment imagined what was going on between her young daughter and her husband in the prime of his manhood, had been blind since birth. Despite this blindness, which fate had ordained for her, her charm and beauty made her attractive to men. She had become extraordinarily lovely, her body beautifully sculptured as if from marble, her eyes flowing with the blueness of the sea, blind to their own beauty. This blindness of hers gave her a certain poetic aura and a touch of humanity and nobility. This aura was brightened when she pinned up her two long, soft plaits forming a beautiful golden crown on her head. Like the queen of an ancient mythic world she reigned with mystery and charm over this old seaside town.

Aziza’s mother came from a prosperous family whose men had traditionally worked at the docks. She married a rich man who gave her a child, Aziza, and after his death from typhoid their wealth was combined. She was then free to choose another husband and, because she was still young and had a great deal of money and beauty, her blindness didn’t affect her marriage prospects. Many from the city approached her seeking her love and from amongst them she chose the one who became a man to her and to her daughter, Aziza. Aziza was the image of her mother except for a caprice of nature – her skin was slightly brown and her honey-coloured eyes were those of her father – a living reminder which the mother never saw. Nor did she notice the dreamy, profound look in those eyes with their mysterious seductive quality, bewitching all who looked on her.