6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

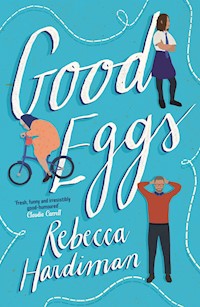

'A witty, exuberant debut' People magazine 'A mix of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Frye and a Maeve Binchy novel [...] perfect to savor as we emerge from this particular winter.' American Booksellers Association indie pick 'A delightfully friendly and welcoming read' LoveReading Meet the Gogartys: cantankerous gran Millie (whose eccentricities include a penchant for petty-theft and reckless driving); bitter downtrodden stepson Kevin (erstwhile journalist whose stay-at-home parenting is pushing him to the brink); and habitually moody, disaffected teenage daughter Aideen. When Gran's arrested yet again for shoplifting, Aideen's rebelliousness has reached new heights and Kevin's still not found work, he realises he needs to take action. With the appointment of a home carer for his mother, his daughter sent away to boarding school to focus on her studies and more time for him to reboot his job-hunt, surely everything will work out just fine. But as the story unfolds - and in the way of all the best families - nothing goes according to plan and as the calm starts to descend into chaos we're taken on a hilarious multiple-perspective roller-coaster ride that is as relatable as it is far-fetched. Good Eggs is a heady cocktail of that warmth and wit of Marian Keyes, Caitlin Moran and TV's Derry Girls.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

First published in the United States in 2021 by Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc., New York.

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2021 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Rebecca Hardiman, 2021

The moral right of Rebecca Hardiman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 274 7

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 275 4

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 276 1

Printed in Great Britain

Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House, 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.allenandunwin.com/uk

To my mother and grandmother

1.

Millie

Three-quarters of the way to the newsagent’s, a trek she will come to deeply regret, Millie Gogarty realizes she’s been barrelling along in second gear, oblivious to the guttural grinding from the bowels of her Renault. She shifts. Her mind, it’s true, is altogether on other things: the bits and bobs for tea with Kevin, a new paperback, perhaps, for the Big Trip, her defunct telly. During a rerun of The Golden Girls last night, the ladies had just been mistaken for mature prostitutes when the screen went blank (silly, the Americans – overdone, but never dull). After bashing the TV – a few sturdy blows optimistically delivered to both sides in the hope of a second coming – she’d retreated to her dead Peter’s old sick room where she’s taken to sleeping ever since a befuddling lamp explosion had permanently spooked her from the second floor. Here, Millie had fumbled among ancient woollen blankets for her battery-operated radio and eventually settled down, the trusty Philips wedged snugly between a naked pillow and her good ear, humanity streaming forth. Her unease slowly dispelled, not unlike the effect of a five-o’clock sherry when the wind of the sea howls round her house post-apocalyptically. Even the grimmer broadcasts – recession, corruption, lashing rain – can have an oddly cheering effect: somewhere, things are happening to some people.

Now a BMW jolts into her peripheral vision, swerves sharply away – has she meandered? – and the driver honks brutally at Millie, who gives a merry wave in return. When she stops at a traffic light, the two cars now parallel, Millie winds down her window and indicates for her fellow driver to do likewise. His sleek sheet of glass descends presidentially.

‘Sorry!’ she calls out. ‘I’ve had a frozen shoulder ever since the accident!’ Though her injury and her dodgy driving bear no connection, Millie feels some explanation is due. She flaps her right elbow, chicken-wing style, into the chilled air. ‘It still gets quite sore.’ Millie offers the man, his face a confused fog, a trio of friendly, muffled toots of the horn and motors on past.

Before heading to the shop, Millie had phoned her son – technically her stepson, though she shuns all things technical and, more to the point, he’s been her boy and she his mum since his age was still measured in mere months. Millie began by relaying the tale of the unholy television debacle.

‘Blanche had checked the girls into a hookers’ hotel without realizing,’ Millie explained, ‘and the police –’

‘I’m just bringing the kids to school, Mum.’

‘Would you ever come down and take a look? I can’t bear to have no telly.’

‘Did you check the batteries?’

‘It doesn’t run on batteries. It’s a television.’

‘The remote batteries.’

‘Aha,’ says Millie. ‘Well now, how would I –?’

‘Let me ring you in two ticks.’

‘Or you can take a look when you come for supper?’ ‘Sorry?’

‘Remember? It’ll be your last chance, you know. I leave Saturday.’

‘Fully aware.’

‘I may never come back.’

‘Now you’re just teasing me.’

‘And bring one of the children. Bring all of the children! I’ve got lamb chops and roasties.’

She had, in fact, neither. A quick inspection of the cabinet, during which she held the phone aloft, blanking briefly that her son was on the line, yielded neither olive oil nor spuds. A glimpse in the fridge – the usual sour blast and blinding pop of light – revealed exactly one half-pint of milk, gone off, three or four limp sprigs of broccoli, and a single cracked egg.

‘Or maybe I’m the cracked egg,’ she muttered as she brought the receiver to her ear.

‘That,’ her son said, ‘has never been in question.’

Once inside Donnelly’s, Millie tips her faux-fur leopard-print fedora to one and all. Millie Gogarty knows many souls in Dún Laoghaire and villages beyond – Dalkey, Killiney – and it’s her self-imposed mission to stop and have a chat with anyone whenever, wherever possible: along the windy East Pier, in the shopping centre car park, standing in the bank queue (she would have no qualms about taking her coffee, used to be complimentary after all, in the Bank of Ireland’s waiting area), or indeed right in this very shop.

She sidles up to Michael Donnelly, Jr, the owner’s teenage, pockmarked son who slouches behind the counter weekdays after school.

‘Did you know in three days’ time Jessica Walsh and myself will be in New York for the Christmas? My great-great-great-grandnephew’ – she has slipped in an extra great or two, as is her wont – ‘used to live in Ohio, but we’re not going there. Sure, there’s nothing there! I visited him once … oh, I don’t know when, it’s not important.’ She crosses her arms, settles in. ‘Christmas morning and not a soul in the street. Kevin and I – he’d just gone eighteen – we took a walk, mountains of snow everywhere, and there we were standing in the middle of the street calling out, “Hello? America? Is anyone there?”’

‘That so, Mrs Gogarty?’ Michael says with a not entirely dismissive smile. He turns to the next customer, Brendan Doyle, whom Millie knows, of course, though Brendan appears to be deeply engrossed in his scuffed loafers.

She beams at them both, trailing away towards the tiny stationery section, a shelf or two of dusty greeting cards whose existence would only be registered by her generation. The young no longer put pen to paper. They text message. Her own grandchildren are forever clicking away at their mobiles with a frenzied quality Millie envies; she can’t remember the last time communication of any kind felt so urgent.

She selects a card embossed with a foil floral bouquet – ‘It’s Your Special Day, Daughter!’ – and reads the cloying message within. Once in hand, the itch to swipe the thing, the very last thing under the sun that Millie Gogarty, daughterless, needs, gains powerful momentum, until she knows that she must, and will, take it.

She checks the till. Michael is ringing up Brendan’s bars of chocolate. The last time he’d crossed her path was in the chemist’s – he’d been buying a tube of bum cream, the thought of which now makes her giddy. Her pits dampen as she prods open the cracked folds of her handbag, pushes its chaotic contents – obsolete punt coins, balls of hardened tissue, irrelevant scribbles – to the depths so that it gapes open, a mouth begging to be fed. Her stomach whoops and soars. Her heart, whose sole purpose for days upon days has been the usual, boring biological one, now thumps savagely. With a wild, jerky motion she will later attribute to her downfall, she plunges the card into her bag.

Millie breathes. Feigning utter casualness, she plucks another card, this one featuring a plump infant and an elephant. She smothers a laugh. Perhaps Kevin’s right: perhaps I’ve finally gone mad! She steals another glance at Michael, who meets her gaze, nodding imperceptibly, and so she chuckles, as if the words inside particularly strike her fancy. Millie has sensed a calling to the stage all her life and she holds out a secret hope that she might still be discovered. Indeed, for a moment, Millie Gogarty marvels at her own audacity, pulse pounding yet looking for all of Dún Laoghaire as calm as you like. Her mind turns to supper – one of the grandchildren could turn up – and so she boldly heads towards a display of crisps and nicks a packet of cheese and onion Tayto and a Hula Hoops.

Flooded with good cheer and relief, she fairly leaps back into her car, the spoils of the morning safely tucked beside her. She’s situating her left foot on the clutch, right foot poised to gun the engine and soar off back to her home, Margate, when she hears a timid knock on her window.

It’s Junior from the shop, not a smile on him. A panicky shot of darkness seizes her. Millie reluctantly draws down her window.

‘I hate to do this, Mrs Gogarty, but I have to ask you to come back in.’

‘Did I leave something behind?’

He glances at her bag. ‘You’ve a few things in there I think you haven’t paid for.’

There follows a pause, long and telling.

‘Sorry?’ she says, shifting into reverse.

‘I’m talking about that.’ He jabs a fat, filthy finger at her handbag. The boy – barely sixteen, she reckons, the twins’ age, probably in fifth year – yo-yos his eyes from the steering wheel to the bag, back to the wheel. ‘My dad said I was to phone the guards if it happened again.’

Phone the guards!

Millie assembles her most authentic aw-shucks grin, hoping to emit the picture of a hapless, harmless granny. But her body betrays her: her face boils; pricks of perspiration collect at her hairline. This is the sorry tale of all the oldies, the body incongruent with the still sharp mind – tumours sprouting, bones snapping with a mere slip on ice, a heart just giving up one day, like her Peter’s. Millie’s own heart now knocks so violently, for the second time today, that she has the image of it exploding from her chest and flapping, birdlike, away.

Junior’s still staring at her. She puts the back of her hand up to her brow, like a fainting lady from an earlier century; she can’t bear to be seen. Then a single, horrid thought filters through: if the police become involved, Kevin will find out.

Kevin cannot find out.

He’s already sniffing around, probably trying to build a case, with a stagey, lethal gentleness that terrifies her, to stick his poor mum into some godforsaken home for withered old vegetables. Millie Gogarty has no plans to move in with a bunch of wrinklies drooling in a corner. Her dear friend Gretel Sheehy was abandoned in Williams House, not five kilometres down the road. Gretel, needless to say, didn’t make it out.

Now a second, equally ghastly thought: what if her grandchildren, the Fitzgeralds a few doors down, or all of south Dublin gets wind of her thievery? The potential for shame is so sweeping that Millie rejects the idea outright, stuffs it back into her mental lockbox where, wisely or not, she’s crammed plenty of other unpleasantries over the years.

Wildly, she considers feigning an ailment – a stroke, perhaps? It, or something like it, has worked in the past, but she can’t, in her muddled thinking, remember when she last trotted out such a deception and vaguely suspects that it was here in Dún Laoghaire.

‘I’m really sorry,’ Michael says. He’s actually not, despite the acne, a bad-looking lad. ‘The thing is, I’ve already phoned the police.’

2.

Kevin

Kevin Gogarty gets the call over pints at The Brass Bell, one of the city centre’s oldest pubs, known for showcasing promising comedians on its tiny makeshift stage in the upstairs room. Kevin had had his shot at the mic years and years ago, when he’d had the notion of becoming a stand-up comedian. He’d bombed badly with a running gag about blow jobs and priests that he later felt had been ahead of its time. Still, he loves the mahogany carvings and brass beer pulls, the shabby Victoriana of the place, and it’s where he and Mick, his former colleague and best mate, meet on the rare occasion when he can get out on the lash.

Leading up to Christmas week, the pub is mad packed with drinkers – everyone across the land is on the piss. It takes Kevin a full minute, plenty of sorrys and hands landing briefly on strangers’ backs, to nudge through the throngs and arrive at the bar, where he sighs happily: he’s out of the house with Mick, who’s sure to regale him with plenty of suss about the old magazine.

The barmen are on the hustle as ever, pulling pints of ale and stout and cider three, four across, taking orders from customers all down the long bar. It’s miraculous they never fuck it up, adding up your total, making fast change, no till required, mixing up Bacardi and Coke, Southern Comfort and Red, Irish coffee, whatever you like. If barmen ran the country, Kevin thinks, the economy would doubtless not be in the shitter.

Just outside, he can see, despite the cold, tiny huddles of smokers commiserating, blowing out their luxurious cancer plumes. No more smoking indoors any more – who would ever have thought? He feels like an ould fella, but can’t help marvelling at how much Ireland has changed. Used to be this place was smoke-fogged and jammed like this at lunchtime any day of the week. No one has the dosh any longer, given the brutal, embarrassing slaying of the so-called Celtic Tiger. In the few months he’s been carpooling children in his whopping seven-seater, negotiating homework, refereeing sibling rows, cooking up plates of fish and chips and peas, the world seems to have shifted, the air seems to have leaked from the recently buoyant Dublin economy. The days of dossing, of not taking any of it too seriously, are up.

When Kevin’s mobile first rings – unknown caller – he rejects it and then spots and salutes Mick from afar. He hears music competing with the din – ah, Zeppelin. ‘Over the Hills and Far Away.’ A Guinness in each hand, Kevin weaves his way expertly, cautiously, back to the bit of table Mick’s eked out for them, not coincidentally, Kevin is certain, beside two very beautiful, very young women, early twenties if that, a glass and mini-bottle of Chablis before each.

‘Mind if we squeeze in here?’ Kevin says.

The hotter one – wide, clever eyes; breasts that have clearly not been suckled upon, by babies anyway; blinding Yank teeth – regards and dismisses him in the same millisecond. Kevin absorbs her indifference with a wince.

‘Done with work,’ says Mick. ‘For the year anyway.’

‘Ya fucker.’ The two men exchange a lengthy handshake and Kevin’s feeling so generous of spirit – the tree is up, the kitchen stocked with food and drink, Grace’ll be about for a few days anyway, maybe he’ll even get laid, a Christmas miracle! – he throws his arms around Mick.

‘Listen, I might have a lead for you,’ says Mick.

‘Not sure I’m hireable.’

‘Fuck off. You know your man Royston Clive?’

‘You’re joking. Isn’t he meant to be a notorious prick?’

‘Yes, but that notorious prick’s launching something here. He’s looking for someone to run the place. And they’re funded out the arse.’

Kevin’s mobile rings a second time: it’s the same unfamiliar number. A worm of worry begins to grind its way through the anxiety-prone soil of his mind. It could be Grace phoning from the road; it could be Mum with some wretched request. Or it could be Sr Margaret reporting Aideen’s excessive tardiness or that she’s skived off another class. Or it could be Aideen’s run off again or hitchhiked or maybe some sick fucker has his beloved daughter tied up in an abandoned garden shed, a rag wet with chloroform shoved down her gob, ringing him for a ransom …

With his little rebel Aideen, it could be any bloody thing.

Kevin tries to refocus on Mick who’s onto a deliciously salacious tale of a late-night tryst on the publisher’s desk in the offices of his old haunt. This is of particular interest to Kevin as it concerns his old boss, John Byrne, pompous, know-it-all, shiny-faced gobshite that he is. Kevin desperately wants to enjoy this story, wants to deep dive into this dirty little affair with its sordid little details.

‘Now, you may or may not recall,’ Mick lowers his voice, ‘but our esteemed publisher is into role play and I don’t fucking mean Shakespeare.’ Mick leers. ‘You’ll not believe his favourite character of all. No joke now: a naughty schoolboy in dire need of a proper arse-spanking.’ Mick guffaws, flashing greying fangs.

Kevin makes the appropriate responses, the convincing shifting facial gestures, but his mind pulls back to the unfamiliar number just as it flashes up a third time.

‘Give us a sec, Mick,’ he says. Then, into the phone: ‘Kevin Gogarty.’

Despite being only recently unemployed – Kevin has taken to trotting out, in an exaggerated Texan accent, that he is a ‘temporary stay-at-home dad’ – he hasn’t stopped answering the phone as if it may be the printer or the creative director or a sales rep on the line.

‘Mr Gogarty? This is Sergeant Brian O’Connor in Dún Laoghaire Police Station.’

Kevin stiffens. ‘Yes? Is Aideen OK?’

‘Aideen? Sorry? No, I’m sorry having to bother you, but actually we’ve got your mum here. Could we ask you to come in and collect her? She’s in a bit of a state.’

‘What?’ Kevin plugs a thumb into his free ear. ‘Is she alright? What’s happened?’

The hot girls, upon hearing the urgent pitch in Kevin’s voice, immediately stop speaking and look over, but they’re only a background blur to him now.

‘Did she have a fall?’

‘Oh no, she’s fine,’ says O’Connor. ‘Didn’t mean to alarm you. No, she’s in grand shape, physically speaking. It’s just – we’ve had a bit of an incident. She was found with stolen goods in her handbag, I’m afraid.’

Kevin allows for a long moment of silence to ensue during which he experiences a familiar emotional arc that begins at anger, crescendoes into hot rage, and peters out, finally, into a sad little trickle of self-pity. He thanks the policeman, rings off and stares at Mick, who, blissfully single, needs only to worry about where to order his next pint and which footballer will make the gossip page. Mick has no family, no brood of children. Kevin has four children! He is still, eighteen years later, reeling from the shock of four. Two boys and two girls to lie awake and worry over at three in the morning, to look after and cook for, to mould and shape into good and honourable souls. To say nothing of his pilfering mother who is, again, in need of rescue. He drains his drink, gets up.

‘Sorry, Mick. I’ve got to go.’

‘Nothing serious?’

‘Oh no, strictly your run-of-the-mill shite,’ Kevin says bitterly. ‘My mother just got picked up for shoplifting. She’s in with the guards driving them all, no doubt, to the brink of mass suicide. Jim Jones, was it? He had nothing on Millie Gogarty.’

3.

Aideen

Three kilometres south of Dún Laoghaire, in the small, pretty seaside village of Dalkey, Aideen Gogarty sits at her father’s laptop tapping the word ‘pine’ into the search box on thesaurus.com. She is penning a poem to Clean-Cut, the Irish pop singing sensation who croons mostly remixed mid-’70s and early ’80s soft-rock hits. Clean-Cut, who is, in fact, dishevelled and bewhiskered, sports a wild, moppish bleached blond ’do and is as tall as an American basketballer, in stark and amusing contrast to his four tidy and diminutive backup singers. After considering each synonym on offer – ache, agonize, brood, carry a torch, covet, crave, desire, dream, fret, grieve, hanker, languish for, lust after, mope, mourn, sigh, spoil for, thirst for, want, wish, yearn, yen for – Aideen rejects the lot as embarrassing and a bit crap.

She scans the bookshelf and the piles of paper inundating Dad’s desk in search of his thesaurus from university, which was his father’s before him, preferential to Aideen on the grounds that it’s old school and therefore authentic. Aideen yearns – hankers? – to be authentic.

As she spots the ragged Roget’s cover, she happens upon a photograph of a beaming, freckled schoolgirl in a brown uniform, a scarlet notebook clutched in her arms. It looks to be the cover of some sort of academic brochure. A cringeworthy photo – what eejit would willingly pose for their school’s poxy PR? – but, curious, Aideen studies the other pictures splayed across the glossy foldout: there’s a gaggle of girls bearing cricket bats on a pristine pitch, arms thrust upward in victory; a ‘Residential Room’ featuring fuchsia try-hard cushions; and, the most commanding image of all, a wrought-iron sign on a grassy knoll that reads MILLBURN SCHOOL FOR GIRLS. The slogan beneath, HONOUR, LEADERSHIP & ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, is not the one Aideen’s heard regarding the place: ‘Noses up, knickers down.’

As she folds over the final page, Aideen is surprised to see, stapled in the top right-hand corner of an otherwise blank application form, a photograph of herself, one tiny yet hideous spot quite visible on the bridge of her nose.

Aideen tries to process what is so obvious and yet unbelievable. But all she comes up with is, Huh? She mentally combs through recent family aggro, trying to find a precedent for such a radical and covert move. Yes, she’s ‘acted out’ lately – deliberately cracking her sister’s mirror (no regrets there), dipping into Mum’s handbag once too often, getting in a touch of trouble at school. And, then, her marks are a bit shit.

Still. Is the fact that the application form has not been filled out a good sign?

But the photo.

She hears a yell and through the window spies her younger brother, Ciaran, monkeying across the bars on his play set in the back garden. Behind him, dull clouds hover sharply against a dingy Dublin sky. Ugh, and there’s her twin sister, Nuala (codename Nemesis). Nemesis meanders towards the front of the house. She is scanning the horizon, no doubt, for boys, flipping her deep black, overgrown mermaid’s mane first left, then right, then left again, as if her hair is crossing the road, as if she’s a California chick from a Katy Perry video when she’s actually a vacuous phony from boring, provincial Dalkey.

Aideen checks the laptop’s internet history over the last week and, with sinking heart and a sudden desire to take to her bed, she sees quite plainly that Dad’s been visiting the Millburn website as often as three and four times a day.

Fuck.

She begins to hunt round his shelves and drawers, for what, she’s not exactly certain, confirmation, evidence, one way or the other – please, let it be the other – that she isn’t totally and irreversibly doomed. Millburn is a boarding school, probably filled with haughty, confident girls who will hate her. She hears the back door slam. Quickly, Aideen slides the brochure beneath its original mess just as Nemesis and one of her newer, nicer tagalongs, Gavin Mooney, appear in the doorway.

Her sister’s beauty is a painful fact of Aideen’s life, or maybe the painful fact, especially poignant because of their twinhood. It feels to Aideen as if the girls are compared, directly or indirectly, nearly every day of their lives, and though no one has ever overtly stated it, Aideen knows she’s the brain, not the beauty. A modelling scout once stopped Nemesis in Stephen’s Green, forked over his business card and winked at her and said she ought to get her headshots done, that she was ‘a vision’ (of utter bitchery) and he had a studio in town where they could shoot. Nemesis had Sellotaped the card to her dressing mirror and gushed about it to the point of vomit-inducing boredom (hence, the mirror’s righteous destruction). Boys ring her every day. No male has ever phoned Aideen Gogarty, a fact about which she feels an undue degree of shame and sorrow. She is desperate that no one be privy to this, ever.

And then there’s Mum and Dad, nauseating on the topic of Nemesis. Our Nuala’s so sporty, she’s the top acrobat at school! Our Nuala’s so talented, she got the lead in the school play! Our Nuala’s so kind, she made this painting of our perfect family and it’s all so lovely!

There once was a girl who seemed sweet An actor, gymnast, athlete

With dark stunning hair That made all the boys stare

She’s fooled the world, thus I retreat.

‘I need the computer,’ Nuala announces in her entitled way, bouncing impatiently on tiptoes.

‘Hiya,’ Gavin mumbles. He wears a navy tracksuit and white-on-white Puma high-tops.

‘You could say hello to Gavin.’

But Aideen is distracted by the gothic Millburn School lettering displayed blatantly on her father’s computer screen. Determined that her twin, of all people, not know about this – boarding school! – she ignores Nuala and steps backward to block the screen.

‘Ooh, what’s the big secret?’ Nemesis sniffs evilly.

‘Hi, Gavin.’

‘Whatever,’ says Nemesis. ‘I need the computer.’

‘I’m using it,’ says Aideen.

‘I need it.’

‘Fuck off.’

Nemesis slits her eyes at Aideen, but since a male is present, she merely huffs off, Gavin trotting after her, like all of them. Aideen decides to snoop further, later, when everyone’s asleep. This, in the wee hours, is when she gleans any real information about the goings-on in the Gogarty household. Mum and Dad talk a big game about openness and honesty and all that bollocks, but then they go and hide anything of interest or value. She once found a pregnancy test in her mother’s loo – negative, she eventually understood after studying the box and then the stick. Which probably explained why Mum had seemed so blue in the days that followed. Unbelievable to Aideen that her mum would want more kids when she’s always at work!

Then there was the letter addressed to Dad, which Aideen spied in ripped shards at the top of the bin: ‘We’re sorry to inform you that the position for which you applied …’

Aideen heads to the kitchen, warms up the lasagne per her father’s tiresome instructions – he’s an over-explainer and a worrier. She piles more logs onto the dwindling fire, pokes at it, still shell-shocked. It’s true that the Gogarty household has been strained, especially since her mother’s tourism consultancy firm landed some big new client and Dad lost his job in magazines. Nowadays he’s often to be found moping about with huge, needy eyes, inserting himself into every bloody moment. It’s equally true that, though her parents bang on about how clever and observant she is, that she has ‘emotional intelligence’ (which means …?), Aideen knows she constantly disappoints them. She makes ‘bad choices’, which is parent-speak for not the choices they would make. Fine, OK, but to ship her off like an outcast to live with a bunch of strangers?

‘Aideen! Is this the site you were looking for?’ Nemesis calls out from the study, sing-song mockery in her voice, and, as Aideen enters, a sadistic, shitty little grin on her face. These are precisely the moments Aideen most misses Gerard, her older brother who left in September to take up a psychology course at University College Cork, and who, unlike her parents, actually listens.

Gavin, head down, eyes averted, begins to retreat backward from the room. Aideen approaches the computer screen and sees that it’s filled with photos of magnified medical blobs. It’s a webpage of spots: crusty lesions, bulbous, bursting whiteheads. Nemesis throws her head back in a witch’s cackle and zooms in on a black-and-white retro advertisement of a distressed, spotty 1950s teen above a dialogue bubble that says, ‘Doctor, will these pimples scar my face?’

Nuala is right: Aideen is not attractive enough, she never will be, which is truly tragic because, above all else, she secretly covets being coveted. Clean-Cut is lovely to her at HMV record shop signings and backstage VIP fan zones and even when he tweets her directly, which he’s done twice, but that’s more about her being a loyal fan, someone who’s worshipped the singer and his short crew since they were nobodies from Rathfarnham. What boy, what real boy, would ever choose Aideen Gogarty, especially in the shadow of her twin’s radiance? Even her horrible family doesn’t want her. Some ugly island of fury, or maybe injustice, or maybe just everyday sibling envy, loosens in Aideen, rekindling a dormant spark of self-loathing that’s been festering for months.

Which may or may not justify what happens next. She snatches the first weapon at hand – the fire poker she’d unintentionally left stuck between two now blazing logs in the hearth, as it happens. It is a glowing, sizzling neon hot rod; it is a tool to brand cattle with or some grotesque instrument of CIA torture.

It would do perfectly.

Aideen launches at her sister. Both scream. Nemesis runs and Aideen gives chase and they race round the first floor, as they used to, happily, in earlier years. Though Nuala is six minutes older, Aideen was the unquestionable leader of their childhood larks. She made most executive decisions: Scrabble over Monopoly, bunk-bed rotations (back when they shared a room), who would hide and who would seek. Nuala shadowed Aideen for years until, gradually, inexplicably, she didn’t. Now they slam with violence through the grand, high-ceilinged rooms, Aideen emitting bloodcurdling roars to petrify the horrible troll whose simultaneous yells are much girlier. At some point, Gavin pursues them and yells at them to stop and then gives up.

Of course, Aideen has no intention of actually burning flesh; she’s just trying to terrify the silly bitch. She’ll later try to explain this, though no one will listen. No one ever does. The sisters end up duking it out where it started, fireside, in a silence punctuated by the odd grunt. Hair is yanked, skin slapped, pinches exchanged. When Gavin finally reaches them and ends it, Aideen is straddling her sister, whose wispy, slender arms are pinned down by each of Aideen’s bony knees, the poker towering high, trembling and still trailing a thin whisper of smoke above them.

4.

Millie

From her perch on a metal chair in a shoddy, windowless chamber that reeks of cigarettes – oh, for a smoke! – Millie spies her handsome son breezing into the Garda station. He doffs his overcoat, revealing a smart grey jumper and a pair of cuffless woollen trousers. Lean and trim still, Kevin is a man to notice, increasingly distinguished with age. The thick wedge of hair helps, only patchily grey and barely receding. His face, shadowed lightly in stubble, is kind and expressive, a face that Millie would almost call bookish with its strong jaw and brow, and wiry Yeatsian eyeglasses. Given his range of comedic tendencies – a single arched eyebrow to self-efface, frequent squinting in faux scepticism, a throwing up of his massive hands to capitulate – he can easily enchant most rooms: a working man’s pub down the country, a posh soirée, a recent party at the house where Millie was later told (she’d been mysteriously omitted from the guest list) he was carrying on like a celebrity DJ, pushing chairs and tables asunder to fashion an impromptu dance floor.

But will his charm do the trick at Dún Laoghaire Garda Station?

At the moment, he huddles, former footballer that he is, listening intently to Sergeant O’Connor, the man who’d brought her in. She’s often wondered whether Kevin’s athletic prowess – running, tennis, squash – isn’t a direct result of seeing Peter in recovery all those years, as if Kevin grew up bent on avoiding his father’s fate. Now he nods frequently and then seems to interrupt with a lengthy speech, and nods again, arms crossed. All her life, it occurs to Millie, men have convened with other men, making decisions on her behalf. What, she wonders, given this particular situation, might the Golden Girls do?

Finally they’re moving, a single menacing unit, a dark little cloud of doom, towards Millie Gogarty, who has the dizzying sensation that everything is topsy-turvy, that he’s the adult and she the naughty child. Has he come to scold or threaten or yell? Or to take pity on his mother and her eccentric ways, to forgive and forget?

‘Are you right there, Mrs Gogarty?’ says O’Connor, once he and a younger officer and her son have scraped their chairs towards her. It’s been ages since a group of men acknowledged, let alone flanked, her, and a lifelong inclination towards the opposite sex nudges her spirits slightly upward. She smiles shyly at them, begins to see that she can rise to this occasion. After all, she conquered Peter’s strokes, three of them; she taught him how to speak again. She suffered through his death and, long before that, the death of Baby Maureen. Surely this is but a blip.

Kevin’s sitting not a foot from her, aloof and stern, unwilling to meet her eyes.

‘Can I get you anything?’ says O’Connor. ‘Coffee, tea?’

Millie declines, then nods her head to show she’s steadfast, prepared.

‘The problem we have here is that this isn’t the first time you’ve taken a few bits from Mr Donnelly’s shop, isn’t that right? You see, he was willing to let it go the once or twice, but now you’re laughing at him – you see my meaning?’

‘Gentlemen,’ says Millie bravely, though there is a detectable quiver in her voice. ‘I believe this is all a bit of a misunderstanding. You see, I was in the shop and my good friend Kara O’Shea, do you know her? She’s the mother of Henry and Dara O’Shea, wonderful sailors, the pair of them, crossed the channel in a boat no bigger than a bathtub, now when was that? No, I don’t suppose –’

‘Sorry,’ Kevin brays, suddenly on his feet. ‘May I have a word with my mother privately, please? Just briefly?’

The room is barely cleared before he whirls around, glaring, and quite definitively, she sees, prone to neither mercy nor amnesia.

‘They want to charge you with shoplifting, Mum,’ he hisses, ‘so the old-lady ding-dong act is not going to fly here.’ An explosive speck of spit soars towards Millie, who instinctively dodges it, watches as it lands on a metal stool that has probably hosted the rumps of hundreds of the town’s most hardened criminals.

Millie wonders if the coppers have gone off to one of those two-way mirror rooms she’s seen on Law & Order to watch the drama unfold. There is, she notes, a boxy window on the wall facing her. She assumes a calm manner, smiles up at her boy who, after all and despite everything, she loves mightily.

‘I would give my eyeteeth,’ says Kevin, ‘to understand exactly why you’re smiling right now.’

‘This can all be sorted. I’ve been going to Donnelly’s for years. I’m a loyal customer.’

‘Loyal customer!’ Kevin’s jaw gapes, his eyes two fierce slits, like eyes a pre-schooler would gouge with a plastic knife into a play-dough face. ‘I’m seriously beginning to wonder if you are compos mentis.’

Millie’s skin prickles. This is just the sort of technical jargon that would be rattling around the brain of someone who’s researching how to make it look as if his mother isn’t the full shilling and ought to be put into a home.

‘Here, just take it all back! I don’t even eat Hula Hoops!’ she cries, upending her bag onto the floor and setting free an astonishing shower of contents. Later, she marvels at her own stupidity since, if the men are indeed bearing witness, she’s just handed them a smoking gun. Out stream the stolen crisps and the birthday card and, with a decided thunk, a single browning banana. Millie snatches this up; in all the excitement of the day, she’s forgotten lunch.

‘Tell me, please, that you’re not going to eat that.’

‘I’m famished.’

‘Look, do you have a notion of a bloody clue how much trouble you’re in? You do realize, don’t you, that if you’re charged, this could make the papers?’

‘Ha!’ she bellows. ‘For feckin’ a packet of Tayto?’

‘For feckin’ every week in the same feckin’ shop! I warned you the last time.’ He gets up, paces the room in tiny tight circles, panther-like. He is working himself up to, or down from, rage – she can’t tell which. ‘They’ve got a list of every item you’ve ever pinched.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Donnelly had CCTV installed a month ago,’ Kevin says.

Millie scrambles to her feet. ‘Please, Kevin! Please! I can’t go to jail! Oh no. Oh no. Oh no.’ Dizzy, she buttresses her palms against the rickety table, which squeaks goofily with every application of pressure. She might indeed collapse, no put-on this time. As a girl she’d pocketed a peppermint or a pencil now and again, but stopped when her father, always solemn, had threatened to report her to the manager who’d surely drag her off to Mountjoy Prison. But these days, she seems to have so little control over her slippery fingers, this terrific itch to take.

Now Millie hears footfalls – a cadre of them – and has a sudden hope that the officers behind the glass have been moved by her, this well-intentioned woman who’s quick with a smile, after all, leaning against a table in an interrogation room begging for mercy. But the steps pass and fade.

‘Hang on now. Calm yourself.’ Kevin steps back, guides her into her chair and sits himself down. ‘No one’s going to jail yet. Let’s not overdo it.’ He begins to reach a hand out to her but stops mid-air. Kevin’s affection feels so often aborted. ‘Look, they want to make a point, they want to show you the seriousness of this. You’ll have to face the charges.’

‘Publicly?’

‘We can have it handled quietly but I can’t promise it won’t get around.’

Millie buries her face into her hands, once one of her better features, now twin claws road-mapped in thick, wormy veins. Dainty, her Peter called them, ladylike.

Her son sighs, knocks on the table gently with his right fist, then rubs his pate to and fro, his most obvious gesture of high stress. ‘They’re willing to come to an agreement … but there are some conditions.’

‘Anything.’

‘You’ll have to admit to the wrongdoing, apologize to Donnelly. And show in good faith that you’re trying to overcome your problem.’

‘Yes, yes, I can do that.’

‘You’ve got to stop this. You understand, Mum? This. Must. Stop.’

Millie lets her head fall, with enormous relief, into her hands. ‘What would I do without you?’

‘There’s one more thing.’ He coughs. ‘We’re going to have to set up a home aide to come into Margate.’

‘A what?’

‘Someone who pops in, a companion –’

‘Into the house?’

‘No, into the horse stable. Yes, into the house. Jesus. The alternative is to face the charges in court. And since they have actual footage of you tucking Donnelly’s knick-knacks into your bag, I don’t much like your chances.’

‘I don’t like the sound of that, Kevin. A stranger in my own home?’

‘Just a few times a week. Twenty hours.’

‘Twenty hours!’

‘It’s a three-month probation period, starting right away, as soon as we can find someone – Mick’s sister does some sort of recruiting, she might be able to help on that front. If you fulfil your end, the charges will quietly go away.’

‘I don’t suppose that’s negotiable?’

‘That is the negotiation, Mum. You’ve committed a crime. You have no leverage here.’

‘I don’t mind the apology bit, that’s fair enough. But the companion …’

‘Better than the alternative.’

Millie bends to collect her spoils and slowly lines them up on the table, one after the other, a menagerie of ridiculous items she neither wants nor needs. If anything, she considers herself anti-materialistic. There’s only a handful of possessions on this earth she gives a toss about – the long-ago photo of Kevin that Peter had first shown her, the missalette from Baby Maureen’s funeral, Peter’s engagement ring – an heirloom emerald-cut emerald flanked by diamonds and worth a pretty penny, as a matter of fact.

‘Shall I have a word with Sergeant O’Connor then?’ says Kevin.

‘Alright,’ she says, ‘yes, OK. We can get that all sorted when I’m back from America.’

‘No, Mum,’ Kevin says, looking away. ‘I’m afraid America will have to be postponed.’

5.

Kevin

The only creatures to greet Kevin as he pushes open his massive front door and sweeps into the cluttered front hall – mucky shoes, an abandoned bowl of Corn Flakes, fuck’s sake! – are Grace’s two tabbies, Beckett and Cat, neither of whom much like him. They meow and brush competitively, incessantly, against Kevin’s trousers. He sighs: more living things need him, and so soon. Aideen has failed to feed the cats. Aideen has also failed to answer her mobile, which he’s tried three times prior to ensconcing his miraculously mute mother back in Margate, only to get Aideen’s rude voicemail: ‘It’s me. You know what to do.’ Beep. On the third call, Kevin had said, ‘And you know what to do.’ He got zero satisfaction from tapping the ‘end’ button on his mobile violently. You can’t even slam down a phone any more. He envisions his daughter upstairs sulking right now, obliviously plugged into her laptop, that talentless silly-boy drivel blasting her fragile eardrums.

Kevin bends to pet Beckett and the cat nips his hand. He swats at the little brute as it scampers away, then calls out, ‘Aideen, Nuala, Ciaran!’ His ceilings are at least fourteen feet tall and every room is cavernous. In order to be heard at the Gogartys’, you must scream. He has, it occurs to him, the very thing he always vowed not to have: a household of screamers.

Kevin contemplates, with mounting tension, all that he must do in the coming hours – update Grace on Mum’s latest dip into petty larceny, though she’s in Dubai, which means it’s probably next Wednesday there; ring up Mick for a line on finding a caretaker; wrap the growing mountain of over-the-top Christmas presents amid the current family goat-fuck; and get some greens down his children’s gullets. One of the only exceptions to Grace’s generally relaxed parenting philosophy is an insistence on the children’s high and varied vegetable consumption. Which is fair enough. Born and raised in England, Grace was the loving, scholarly eldest of five children living with their indefatigable single mother (dad fucked off to a married-but-separated bankruptcy lawyer in the next estate). Theirs was a junk-food household in which crisps stood in for carrots and the thought of eating meat prepared in any way other than fried was scandalous (even the bread was fried). Watching years of her mum in the kitchen and then out of it, juggling a patchwork of low-wage jobs, fuelled Grace’s drive; a career, she saw, was paramount.

The first time Kevin met his future mother-in-law, in fact, she was trying to press a plate of chips and sausage on him. It was late for Grace’s mum, but not for Kevin and Grace, just in after a few pints at her local in Surrey. They were on break from college in England where they’d met and had hours of night to go. Grace had come up behind her mum in the kitchen and wrapped her arms around her and remained like that. As if familial affection wasn’t a quick peck or a clap on the back or an almost embarrassing thing to be got through. It was as natural as breathing and something to linger on. They were all like that, the whole lot of them. Grace told her mum not to mind Kevin one bit because her boyfriend – that was the first time she’d said it – was more than capable of making his own bloody food. ‘Am I?’ he’d said, pulling a panicked face. His mother-in-law had laughed – she was an easy laugher, like her daughter. What an excellent quality, he’d thought, a direct and effortless access to joy. Later, Grace had whisked her brothers and sisters off to bed and brought him into the lounge and shut the door and put on a film – Weekend at Bernie’s – though they never got past the first scene. It became code. You want to watch Weekend at Bernie’s?

Now Kevin lumbers into the kitchen and pours a generous glass of Malbec into the last clean receptacle available: a plastic dinosaur sippy cup still somehow in rotation. Gradually he becomes aware of a dim, faraway noise, a thudding, like a plank of wood being knocked repeatedly. Kevin heads towards the back of the house where the pounding grows louder. It’s Nuala standing outside thrashing her fists against the back door. As he unlocks it, he starts in with ‘I told you lot to stop –’

‘Daddy!’ she screams, lunging into his arms. She’s frigid; her nose is alcoholic-red and streaming. She simultaneously cries and talks; she is a mess of blubbering wet.

‘Slow down, pet, hang on,’ he says, patting her back and ushering her into the house. ‘Take it easy.’ How many women, he wonders, must he comfort in one day?

But then, here’s his Nuala, the most cheerful and confident of his crew, clinging to him just as she used to, like they all used to. So he holds her. She feels insubstantial, so light, in his arms. He forgets how young and innocent, how tiny and unworldly, how vulnerable his children are, and then he thinks: what kind of a total gobshite forgets this? Her shampoo smells disturbingly of manufactured coconut and he wonders about its toxicity. He kisses Nuala’s head once and then again.

‘Oh my God, I was outside forever,’ she squeaks between gulps of air. Kevin brings her through to the kitchen, gets out the cocoa and the sugar and puts milk on the boil.

‘Poor darling,’ he says. ‘How did you ever manage to lock yourself out?’

‘Aideen did it!’

Kevin slaps the countertop with his palm. Which hurts.

‘And she came at me with the fire poker,’ says Nuala. ‘She actually tried to burn me.’

‘Bloody hell! You shouldn’t have to …’ He squeezes her shoulder. ‘Where’s Ciaran?’

‘Neighbours’.’

He exhales. ‘And where is Aideen now?’

‘I don’t know,’ she says, ‘and I don’t care.’

The need to avenge his victimized daughter – nearly burnt and then put out of the house in arctic weather! – coupled with the need to hunt down her assailant, to project blame for this chaos onto his clever, complicated, perpetually miserable teen, is so powerful it practically fells him on his ass. He vaults up the staircase taking two, three, steps at a time with his lean runner’s legs and bounds towards her door, strictly verboten to all Gogartys without a ridiculous series of knocks and gentle requests for permission to enter.

Tonight, he charges in. The room is an accurate representation of his daughter’s age or state of mind or both. Other than a shrine to Clean-Cut in pristine condition, disorder reigns. Cluttering the floor: a stick of deodorant fuzzy with carpet fibres, various inside-out denims and socks, a Dunnes Stores shopping bag from which spills a handful of bras acquired during a recent mother–daughter shopping venture, which, as so many recent outings tend to do, had run afoul. Beside Aideen’s bed sits a mug of cold tea, a milky skin stretched taut across it, and a plate of this morning’s toast crusts – Aideen, in her growing hermitry, has taken to eating meals in her room.

Kevin checks every other room in the house, each inspection more frantic than the last so that, in his hurry, he stubs his thick bullet of a toe hard on the iron frame of Gerard’s bed and gives himself over to a loud, satisfying ‘Goddammit!’ He bounds down to the basement – sometimes Aideen hides out down there on a mouldy beanbag chair reading in the crawl space where they keep the luggage and where he’s asked her a hundred times not to be. But there’s no sign of her.

He returns to the kitchen, breathing heavily now, and snaps up his mobile. He tries Grace’s phone and then Gerard’s – Aideen sometimes confides in her older brother – but no answer. Kevin worries about Gerard – his general lack of ambition given the cutthroat state of the world, especially when there are so many pubs to frequent – but he’s eighteen and Kevin mercifully no longer needs to keep track of him.

He can reach no one.

Kevin delivers Nuala, fully recovered, a mug of cocoa. Pacing, he gulps his wine, lays out the facts of his shite day: he’s had to collect his mother from the police station; the whereabouts of his wayward daughter are unknown (at least he hasn’t totally banjaxed things up, he thinks grimly, at least the other three are safe, alive); his wife, as usual, can provide neither advice nor support – she is pontificating from a podium or courting international clients at a hush-hush private club or eating fried samosas in a desert tent.

As he peels open the last tin of cat food, his mobile rings.

‘Did something happen up there?’ It’s Mum.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Aideen’s here but she won’t say a word.’

‘Aideen’s at your house?’

‘I’m only delighted to have her. Any chance you could come down and have a look at the TV? We could use a bit of distraction. What’s the film about the American prostitute with the teeth who goes shopping? What’s it called, Aideen?’

‘Can she stay with you tonight?’

‘She won’t want to, Kevin.’

‘Tell her she has no choice. She caused a whole kerfuffle down here and I need to clear the air.’

‘Pretty Woman, yes, that’s it. Brilliant girl.’

Kevin puts down the phone and heads directly to his desk, where he finds the application for Millburn School.

6.

Millie

After Kevin dropped her home, Millie had retrieved the bottle of sherry normally reserved for special occasions (though special is clearly not the apt adjective here – ‘ghastly’, say, or ‘horrific’ may be better descriptors). Into the kitchen went Millie to fetch a glass when she spotted the red answering-machine light aglow and listened, with a shudder, to its single, dreadful message.

‘You wouldn’t per chance have that spare travel pillow you mentioned that I could bring aboard? Don’t bother yourself at all, but if you put your finger on it, that’d be grand.’

Jolly Jessica. Millie had forgotten about JJ, the driving force behind their New York City trip, who, half a year ago, had triumphantly written ‘Big Apple’ in red biro on the 20 December box of her Famous Irish Writers kitchen calendar below a moody portrait of Brian Friel. What a mockery of their months spent poring over hop-on-hop-off bus tour pamphlets and Broadway listings with the travel agent in town, two silly old biddies telling each other over coffee and cribbage how ludicrous it was, then having the courage to make it possible – only to have it, in fact, become impossible once more! It was enough to reduce Millie’s already depleted spirits to despair, full stop.