INTRODUCTION

I. ON SOME CHARACTERISTICS

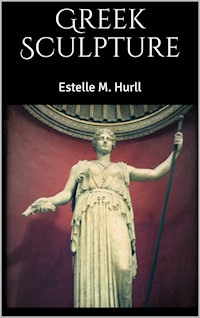

OF GREEK SCULPTURE.The history of Greek sculpture covers a period of some eight

or nine hundred years, and falls into five divisions.[1]The first is the

period of development, extending from 600 to 480 B. C. The second

is the period of greatest achievement, under Phidias and his

followers, in the Age of Pericles, 480-430 B. C. The third is the

period of Praxiteles and Scopas, in the fourth century. The fourth

is the period of decline, characterized as the Hellenistic Age, and

included between the years 320 and 100 B. C. The fifth is the

Græco-Roman period, which includes the work produced to meet the

demand of the Roman market for Greek sculpture, and which extends

to 300 A. D.[1]See Gardner'sHandbook of Greek

Sculpture, page 42.Modern criticism differentiates sharply the characteristics

of the several periods and even of the individual artists, but such

subtleties are beyond the grasp of the unlearned. The majority of

people continue to regard Greek sculpture in its entirety, as if it

were the homogeneous product of a single age. To the popular

imagination it is as if some gigantic machine turned out the Apollo

Belvedere, the Venus of Milo, the Elgin Marbles, and all the rest,

in a single day. Nor is it long ago since even eminent writers had

but vague ideas as to the distinctive periods of these very works.

Certain it is that all works of Greek sculpture have a particular

character which marks them as such. Authorities have taught us to

distinguish some few of their leading characteristics.The most striking characteristic of Greek art is perhaps its

closeness to nature. The sculptor showed an intimate knowledge of

the human form, acquired by constant observation of the splendid

specimens of manhood produced in the palæstra. It is because the

artist "clung to nature as a kind mother," says Waldstein, that the

influence of his work persists through the ages.Again, Greek art is distinctly an art of generalization,

dealing with types rather than with individuals. This

characteristic is of varying degrees in different periods and with

different sculptors. It is seen in its perfection in the Elgin

Marbles, in exaggeration in the Apollo Belvedere, and at the

minimum in the work of Praxiteles. Yet it is everywhere

sufficiently marked to be indissolubly connected with Greek

sculpture.The quality of repose, so constantly associated with Greek

sculpture, is another characteristic which varies with the period

and the individual sculptor. Between the calm dignity of the

portrait statue of Sophocles and the intense muscular concentration

of Myron's Discobolus, a long range of degrees may be included. Yet

on the whole, repose is an essential characteristic of the best

Greek sculpture, provided we do not let our notion of repose

exclude the spirited element. Fine as is the effect of repose in

the Parthenon frieze, the composition is likewise full of spirit

and life.A distinguishing characteristic of the best Greek sculpture

is its simplicity. Compared with the Gothic sculptors, the Greeks

appear to us, in Ruskin's phrase, as the "masters of all that was

grand, simple, wise and tenderly human, opposed to the pettiness of

the toys of the rest of mankind." Their work is free from that

"vain and mean decoration"—the "weak and monstrous error"—which

disfigures the art of other peoples.As we turn from one Greek marble to another in the great

sculpture galleries of the world, the best features of the art

impress themselves deeply even upon the untutored eye. The Greek

instinct for pose is unfailing and unsurpassable. Standing or

seated, the attitude is always graceful, the lines are always fine.

The best statues are equally well composed, viewed from any

standpoint. The camera may describe a circumference about a marble

as a centre, and a photograph made at any point in the circle will

show lines of rhythm and beauty.The faultless regularity of the Greek profile has passed into

history as the accepted standard of human beauty. The straight

continuous line of brow and nose, the well moulded chin, the full

lip, the small ear, satisfy perfectly our æsthetic

ideals.The art of sculpture was an essential outgrowth of the Greek

spirit, and perfectly suited the requirements of Greek thought. In

the words of a recent writer, "it was the consummate expression in

art of the genius of a nation which worshiped physical perfection

as the gift of the immortals, which honored the gods by athletic

games and choral dances, and whose deities wore the flesh and

shared the nature of men."[2]It was moreover a

national art, entering into every phase of public life, and

embodying the Greek sense of national greatness.[2]FromItalian Cities, by

E. H. and E. W. Blashfield.Greek sculpture can be sympathetically understood only by

catching something of the spirit which produced it. One must shake

off the centuries and regard life with the childlike simplicity of

the young world: one must give imagination free rein. The same

attitude of mind which can enjoy Greek mythology and Greek

literature is the proper attitude for the enjoyment of Greek

sculpture. The best interpreter of a nation's art is the nation's

poetry.II. ON BOOKS OF REFERENCE.

Many learned works on the subject of Greek Sculpture have been

written in various languages. Three standard authorities are the

English work by A. S. Murray, "History of Greek Sculpture," second

edition, London, 1890; the French work by Collignon, "Histoire de

la Sculpture Grecque," Paris, 1892; and the German work by

Furtwängler, translated into English by E. Sellers, "The

Masterpieces of Greek Sculpture," London, 1895. Naturally these

three writers are not always of one opinion, and the student must

turn from one to another to learn all the arguments concerning a

disputed point.For the practical every-day use of the reader who has no time

to sift the evidences on difficult questions of archæology,

Gardner's "Handbook of Greek Sculpture" is an excellent outline

summary of the history of the subject.Charles Waldstein's "Essays on the Art of Pheidias," New

York, 1885, is an exceedingly valuable and suggestive

volume.Two small books, written in a somewhat popular vein, make

very pleasant reading for those pursuing these studies: "Studies in

Greek Art," by J. E. Harrison, London, 1885, and "Greek Art on

Greek Soil," by J. M. Hoppin, Boston, 1897.Besides the works devoted exclusively to the subject of Greek

sculpture, the subject receives due attention in various general

histories of art, of which may be mentioned, Lucy Mitchell's

"History of Ancient Sculpture," Lübke's "History of Sculpture," and

Von Reber's "History of Ancient Art."A valuable bibliography is given in Gardner's

"Handbook."III. HISTORICAL DIRECTORY OF THE MARBLES REPRODUCED

IN THIS COLLECTION.Frontispiece.Terminal bust of

Pericles, after an original by Cresilas. Approximate date, 440-430

B. C. In the British Museum, London.1.Bust of Zeus Otricoli.Considered by Brunn and others a copy from a head of the

statue by Phidias. Later critics do not agree with this opinion,

and Furtwängler calls the head a Praxitelean development of the

type of Zeus created in the time of Myron. Now in the Vatican

Gallery, Rome.2.Athena Giustiniana(Minerva Medica).

Considered by Furtwängler a copy, after Euphranor, of a statue

dedicated below the Capitol, called Minerva Catuliana, set up by A.

Lutatius Catulus. The ægis and sphinx are copyist's additions.

Found in the gardens of the convent of S. Maria sopra Minerva,

Rome. Both arms are restored. Now in the Vatican Gallery,

Rome.3.Horsemen from the Parthenon

Frieze.The frieze of the Parthenon is part of

the decorative scheme of the marble temple of Athena, built during

the age of Pericles (480-430 B. C.) on the Acropolis, Athens, and

decorated under the direction of Phidias. The frieze consisted of a

series of panels or slabs, about 3 ft. 4 in. in height, and was set

on the outer wall of the cella. Being lighted from below, the lower

portion is cut in low relief (1¼ in.) and the upper parts in high

relief (2¼ in.). The panel of the Horsemen is one of the Elgin

Marbles, removed by Lord Elgin from the Parthenon in 1801-1802, and

now in the British Museum, London.4.Bust of Hera.Considered by Murray a copy after Polyclitus. Regarded by

Furtwängler as a "Roman creation based on a Praxitelean model."

Catalogued in Hare's "Walks in Rome" as a probable copy after

Alcamenes. In the Ludovisi Villa, Rome.5.The Apoxyomenos.. A

marble copy of the original bronze statue by Lysippus, who

flourished in the 4th century B. C. According to Pliny the original

was brought from Greece to Rome by Agrippa to adorn the public

baths. This copy was found in 1849 in the Trastevere, Rome, and is

now in the Vatican Gallery.6.Head of the Apollo Belvedere.According to Gardner, a marble copy (Roman) of a bronze

original of the Hellenistic Age (320-100 B. C.). Some (Winter and

Furtwängler) have assigned the original to Leochares, a sculptor of

the 4th century, and others to Calamis, in the 5th century. This

copy was found in the 16th century at Antium, and was purchased by

Pope Julius II. for the Belvedere Palace. Now in the Vatican

Gallery, Rome.7.[...]