0,91 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seltzer Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A collection of 15 pictures (in black and white) with a portrait of the painter with Introduction and interpretation by Estelle Hurll. According to Wikipedia: "Tiziano Vecelli or Tiziano Vecellio (c. 1488/1490 – 27 August 1576) known in English as Titian was an Italian painter, the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. ... Estelle May Hurll (1863–1924), a student of aesthetics, wrote a series of popular aesthetic analyses of art in the early twentieth century.Hurll was born 25 July 1863 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, daughter of Charles W. and Sarah Hurll. She attended Wellesley College, graduating in 1882. From 1884 to 1891 she taught ethics at Wellesley. Hurll received her A.M. from Wellesley in 1892. In earning her degree, Hurll wrote Wellesley's first master's thesis in philosophy under Mary Whiton Calkins; her thesis was titled "The Fundamental Reality of the Aesthetic." After earning her degree, Hurll engaged in a short career writing introductions and interpretations of art, but these activities ceased before she married John Chambers Hurll on 29 June 1908."

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 91

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Picture from Carbon Print by Braun, Clément & Co., John Andrew & Son. Sc., TITIAN, Prado Gallery, Madrid

TITIAN - A COLLECTION OF FIFTEEN PICTURES AND A PORTRAIT OF THE PAINTER WITH INTRODUCTION AND INTERPRETATION BY ESTELLE M. HURLL

published by Samizdat Express, Orange, CT, USA

established in 1974, offering over 14,000 books

Art books by Estelle Hurll:

Michelangelo

Child-Life in Art

Correggio

Greek Sculpture

Landseer

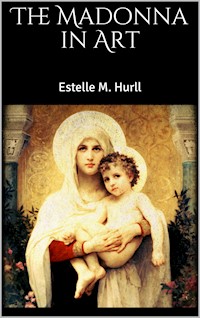

The Madonna

Millet

Raphael

Rembrandt

Reynolds

Titian

Tuscan Sculpture

Van Dyke

feedback welcome: [email protected]

visit us at samizdat.com

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1901, BY HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

I THE PHYSICIAN PARMA

II THE PRESENTATION OF THE VIRGIN (Detail)

III THE EMPRESS ISABELLA

IV MADONNA AND CHILD WITH SAINTS

V PHILIP II

VI SAINT CHRISTOPHER

VII LAVINIA

VIII CHRIST OF THE TRIBUTE MONEY

IX THE BELLA

X MEDEA AND VENUS (Formerly called Sacred and Profane Love)

XI THE MAN WITH THE GLOVE

XII THE ASSUMPTION OF THE VIRGIN (Detail)

XIII FLORA

XIV THE PESARO MADONNA

XV ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST

XVI PORTRAIT OF TITIAN

PRONOUNCING VOCABULARY OF PROPER NAMES AND FOREIGN WORDS

FOOTNOTES

PREFACE

To give proper variety to this little collection, the selections are equally divided between portraits and “subject” pictures of religious or legendary character.

The Flora, the Bella and the Philip II. show the painter’s most characteristic work in portraiture, while the Pesaro Madonna, the Assumption, and the Christ of the Tribute Money stand for his highest achievement in sacred art.

ESTELLE M. HURLL.

New Bedford, Mass. March, 1901.

INTRODUCTION

I. ON TITIAN’S CHARACTER AS AN ARTIST.

“There is no greater name in Italian art—therefore no greater in art—than that of Titian.” These words of the distinguished art critic, Claude Phillips, express the verdict of more than three centuries. It is agreed that no other painter ever united in himself so many qualities of artistic merit. Other painters may have equalled him in particular respects, but “rounded completeness,” quoting another critic’s phrase, is “what stamps Titian as a master.” [1]

To begin with the qualities which are apparent even in black and white reproduction, we are impressed at once with the vitality which informs all his figures. They are breathing human beings, of real flesh and blood, pulsing with life. They represent all classes and conditions, from such royal sitters as Charles V. and Philip II. to the peasants and boatmen who served as models for St. Christopher, St. John, and the Pharisee of the Tribute Money. They portray, too, every age: the tender infancy of the Christ child, the girlhood of the Virgin, the dawning manhood of the Man with the Glove, the maidenhood of Medea, the young motherhood of Mary, the virile middle life of Venetian Senators, the noble old age of St. Jerome and St. Peter, each is set vividly before us.

The list contains no mystics and ascetics: life, and life abundant, is the keynote of Titian’s art. The abnormal finds no place in it. Health and happiness are to him interchangeable terms.

Yet it must not be supposed that Titian’s delineation of life stopped short with the physical: he was besides a remarkable interpreter of the inner life. Though not as profound a psychologist as Leonardo or Lotto, he had at all times a just appreciation of character, and, on occasion, rose to a supreme touch in its interpretation. In such studies as the Flora, where he is interested chiefly in working out certain technical problems, he takes small pains to make anything more of his subject than a beautiful animal. The Man with the Glove stands at the other end of the scale. Here we have a personality so individual, and so possessing, as it were, that the portrait takes rank among the world’s masterpieces of psychic interpretation.

In his best works Titian’s sense of the dramatic holds the golden mean between conventionality and sensationalism. In the group of sacred personages surrounding the Madonna and Child there is sufficient action to constitute a reason for their presence,—to relieve the figures of that artificial and purely spectacular character which they have in the earlier art,—yet the action is restrained and dignified as befits the occasion. The pose of both figures in the Christ of the Tribute Money is in the highest degree dramatic without being in any way theatrical. The tempered dignity of Titian’s dramatic power is also admirably seen in the Assumption of the Virgin. The apostles' action is full of passion, yet without violence; the buoyant motion of the Virgin is unmarred by any exaggeration.

The same painting illustrates Titian’s magnificent mastery of composition. Perhaps the Pesaro Madonna alone of all his other works is worthy to be classed with it in this respect. It is impossible to conceive of anything better in composition than these two works. Not a line in either could be altered without detriment to the organic unity of the plan.

The crowning excellence of Titian is his color. The chief of the school in which color was the characteristic quality, he represents all the best elements in its color work. If others excelled him in single efforts or in some one respect, none equalled him for sustained grandeur. A recent criticism sums up his color qualities succinctly in these words: “He had at once enough of golden strength, enough of depth, enough of éclat; his color, profound and powerful per se, impresses us more than that of the others, because he brought more of other qualities to enforce it.” [2]

Titian’s works easily fall into a few groups, according to the subject treated. In mythological themes he was in his natural element. Here he could express the sheer joy of living which was common to the Venetian and the Greek. Here physical beauty was its own excuse for being, without recourse to any ulterior significance. Here he could exercise unhindered his marvellous skill in modelling the human form along those perfect lines of grace which give Greek sculpture its distinctive character. It is in his earlier period that his affinity with the Greek spirit is closest, and we see it in perfect fruition in the Medea and Venus.

Titian’s treatment of sacred subjects is in the diverse moods of his many-sided artistic nature. The great ceremonial altar pieces, such as the Assumption of the Virgin, and the Pesaro Madonna, are a perfect reflection of the religious spirit of his environment. Religion was with the Venetians a delightful pastime, an occasion for festivals and pageants, a means of increasing the civic glory. These great decorative pictures are full of the pomp and magnificence dear to Venice, full of the joy and pride of life.

Yet in another mood Titian paints the life of the Holy Family as a pastoral idyl. A sunny landscape, a happy young mother, a laughing baby boy, bring the sacred subject very near to common human sympathies.

Some of Titian’s professedly sacred pictures are in the vein of pure genre, painted in a period when this department of art had not yet attained independent existence. We see such works in the St. Christopher and the St. John. These direct studies of the people throw an interesting light upon the painter of ideal beauty: they show an otherwise unsuspected vigor.

The Christ of the Tribute Money stands alone in Titian’s sacred art. The technical qualities are thoroughly characteristic of his hand, but a new note is struck in spiritual feeling. Virile, without coarseness; gentle, without weakness, the chief figure is perhaps the most intellectual ideal of Christ which has been conceived in art.

Titian’s landscapes, though holding an accessory place only in his art, are counted by the critical art historian with those of Giorgione, as the practical beginning of this branch of art. He knew how to express “the quintessence of nature’s most significant beauties without a too slavish adherence to any special set of natural facts.” [3] His imagination interpreted many of nature’s moods, from the pastoral calm environing Medea and Venus to the stormy grandeur of the forest in which St. Peter Martyr met his fate.

It is undoubtedly as a portrait-painter that Titian’s many great qualities meet in their utmost perfection. His feeling for textures, the delicacy with which he painted the hair and the hands; his skill in modelling; his instinct for pose; the infinite variety of his resources, made an incomparable equipment in the secondary matters of portrait painting. To these he added, as we have seen, the two highest essentials of the art, the power of giving life to his sitter, and the gift of insight into character.

Nature made him a court painter; he loved to impart to his sitter that air of noble distinction whose secret he so well understood. Yet he was too large a man to let this or any other natural preference hamper him. Something of himself, it is true, he frequently put into his figures, yet he was at times capable of thoroughly objective work. He stands perhaps somewhere between the extreme subjectivity of Van Dyck and the splendid realism of Velasquez. The noble company of his sitters, emperors, kings, doges, popes, cardinals and bishops, noblemen, poets and beautiful women, still make their presence felt in the world. Theirs was a deathless fame on whom the painter conferred the gift of his art.

Titian’s temperament was keenly sensitive to the influences of his environment, and in his extraordinary length of days, Venice passed through various changes, political, social, artistic and religious, which left their mark upon his work. One cannot make a random selection from his pictures and pronounce upon the qualities of his art. The work of his youth, his maturity, his old age, has each a character of its own. It is this rounding out of his art life through successive stages of growth and even of decay that gives the entire body of his works the character of a living organism.

II. ON BOOKS OF REFERENCE.