0,91 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seltzer Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A collection of 16 pictures (in black and white) reproducing works by Donatello, the Della Robbia, Mino da Fiesoe, and others. According to Wikipedia: "Estelle May Hurll (1863–1924), a student of aesthetics, wrote a series of popular aesthetic analyses of art in the early twentieth century.Hurll was born 25 July 1863 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, daughter of Charles W. and Sarah Hurll. She attended Wellesley College, graduating in 1882. From 1884 to 1891 she taught ethics at Wellesley. Hurll received her A.M. from Wellesley in 1892. In earning her degree, Hurll wrote Wellesley's first master's thesis in philosophy under Mary Whiton Calkins; her thesis was titled "The Fundamental Reality of the Aesthetic." After earning her degree, Hurll engaged in a short career writing introductions and interpretations of art, but these activities ceased before she married John Chambers Hurll on 29 June 1908."

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 92

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

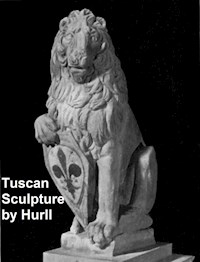

Alinari, photo.John Andrew & Son, Sc., IL MARZOCCO (DONATELLO), National Museum, Florence

TUSCAN SCULPTURE OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY - A COLLECTION OF SIXTEEN PICTURES, REPRODUCING WORKS BY DONATELLO, THEDELLA ROBBIA, MINO DA FIESOLE, AND OTHERS, WITH INTRODUCTION AND INTERPRETATION BY ESTELLE M. HURLL

published by Samizdat Express, Orange, CT, USA

established in 1974, offering over 14,000 books

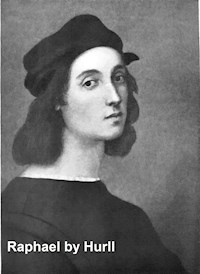

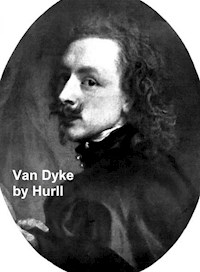

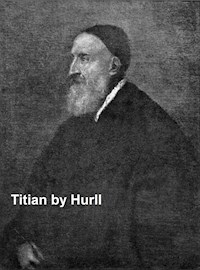

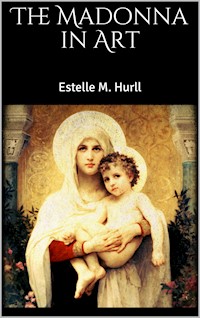

Art books by Estelle Hurll:

Michelangelo

Child-Life in Art

Correggio

Greek Sculpture

Landseer

The Madonna

Millet

Raphael

Rembrandt

Reynolds

Titian

Tuscan Sculpture

Van Dyke

feedback welcome: [email protected]

visit us at samizdat.com

BOSTON AND NEW YORKHOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY COPYRIGHT, 1902, BY HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published March, 1902.

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

I MUSICAL ANGELS BY DONATELLO

II ST. PHILIP BY NANNI DI BANCO

III ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST BY DONATELLO

IV THE INFANT JESUS AND ST. JOHN BY MINO DA FIESOLE

V BOYS WITH CYMBALS BY LUCA DELLA ROBBIA

VI TOMB OF ILARIA DEL CARRETTO (Detail) BY JACOPO DELLA QUERCIA

VII MADONNA AND CHILD (Detail of lunette) BY LUCA DELLA ROBBIA

VIII THE MEETING OF ST. FRANCIS AND ST. DOMINICK BY ANDREA DELLA ROBBIA

IX ST. GEORGE BY DONATELLO

X BAMBINO BY ANDREA DELLA ROBBIA

XI THE ANNUNCIATION BY ANDREA DELLA ROBBIA

XII THE ASCENSION BY LUCA DELLA ROBBIA

XIII TOMB OF THE CARDINAL OF PORTUGAL BY ANTONIO ROSSELLINO

XIV EQUESTRIAN STATUE OF GATTAMELATA BY DONATELLO

XV SHRINE BY MINO DA FIESOLE

XVI IL MARZOCCO (THE HERALDIC LION OF FLORENCE) BY DONATELLO

PRONOUNCING VOCABULARY OF PROPER NAMES AND FOREIGN WORDS

PREFACE

This little collection is intended as a companion volume to "Greek Sculpture," a previous issue of the Riverside Art Series. The two sets of pictures, studied side by side, illustrate clearly the difference in the spirit animating the two art periods represented.

The Tuscan sculpture of the Renaissance was developed under a variety of forms, of which as many as possible are included in the limits of our book: the equestrian statue, the sepulchral monument, the ideal statue of saint and hero, as well as various forms of decorative art applied to the beautifying of churches and public buildings both without and within.

ESTELLE M. HURLL. New Bedford, Mass. February, 1902.

INTRODUCTION

I. ON SOME CHARACTERISTICS OF TUSCAN SCULPTURE IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY.

"The Italian sculptors of the earlier half of the fifteenth century are more than mere forerunners of the great masters of its close, and often reach perfection within the narrow limits which they chose to impose on their work. Their sculpture shares with the paintings of Botticelli and the churches of Brunelleschi that profound expressiveness, that intimate impress of an indwelling soul, which is the peculiar fascination of the art of Italy in that century."

These words of Walter Pater define admirably the quality which, in varying degree, runs through the work of men of such differing methods as Donatello, the della Robbia, Mino da Fiesole, and Rossellino. It is the quality of expressiveness as distinguished from that abstract or generalized character which belongs to Greek sculpture. Greek sculpture, it is true, taught some of these artists how to study nature, but it did not satisfy Christian ideals. The subjects demanded of the Tuscans were entirely foreign to Greek experience. The saints and martyrs of the Christian era were at the opposite pole from the gods and heroes of antiquity. Hence the aim of the new sculpture was the manifestation of the soul, as that of the classic art had been the glorification of the body.

Jacopo della Quercia was one of the oldest of the sculptors whose work extended into the fifteenth century, being already twenty-five years of age when that century began. Standing thus in the period of transition between the old and the new, his work unites the influence of mediæval tradition with a distinctly new element. His bas-reliefs on the portal of S. Petronio at Bologna are probably his most characteristic work. The tomb of Ilaria del Carretto is in a class by itself: "In composition, the gravest and most tranquil of his works, and in conception, full of beauty and feeling."[1]

Donatello is undoubtedly the greatest name in Italian sculpture previous to Michelangelo. The kinship between these two men was felicitously expressed in Vasari's quotation from "the most learned and very reverend" Don Vicenzo Borghini: "Either the spirit of Donato worked in Buonarroti, or that of Buonarroti first acted in Donato." Vitality, force, action, suggestiveness, character, such are the words which spring to the lips in the presence of both masters.

The range of Donatello's art was phenomenal, from works of such magnitude as the equestrian statue of Gattamelata, to the decorative panels for the altar of S. Antonio at Padua. At times he was an uncompromising realist, as in his statue of the bald old man, the Zuccone, who figured as King David. Again he showed himself capable of lofty idealism, as in the beautiful and heroic St. George. Which way his own tastes leaned we may judge from his favorite asseveration, "By my Zuccone." The point is that it mattered nothing to him whether his model was beautiful or ugly, whether he wrought out an ideal of his imagination or studied the character of an actual individual; his first care was to make the figure live. In consequence his art has what a critic has called "a robustness and a sanity" which have made it "a wellspring of inspiration to lesser men."

The only subject practically left out of Donatello's work was woman. Children afforded him all the material he needed for the more decorative forms of his art. For the rest the problems which interested him most were perhaps best worked out in the study of the male figure.

A recent biographer of Donatello, Hope Rea, points out some interesting characteristics of his technical workmanship. In every work subsequent to his St. Mark, "the hair," she says, "is conspicuous by its appearance of living growth." And again, explaining the excellence of his drapery, she shows how he went beyond the ordinary consideration of the general flow and line of the stuffs, to a study of the sections of the folds. Hence drapery with him "is not only an arrangement of lines for decorative effect, or a covering for the figure, but it is a beauty in itself, filled with the living air."

Nanni di Banco is a name naturally associated with that of Donatello, not only on account of the friendship between the two, but from the fact that both worked on the church of Or San Michele. Nanni was one of the smaller men whose work is overshadowed by the fame of a great contemporary. His art has not sufficient distinction to give it a prominent place; yet it is not without good qualities. Marcel Reymond insists that the public has not yet appreciated the just merits of this neglected sculptor. In his opinion the St. Philip was the inspiration of Donatello's St. Mark, while Nanni's St. Eloi had an influence upon St. George.

With Luca della Robbia began the "reign of the bas-relief," as Marcel Reymond characterizes the period of fifty years between Donatello and Michelangelo. Women and children were the special subjects of this sculptor's art, and it is perhaps in the Madonna and Child that we see his most characteristic touch. How well he could represent spirited action, we see in some of the panels of the organ gallery. How dignified was his sense of repose, is seen in the lunette of the Ascension.

Much as he cared for expression,--"expression carried to its highest intensity of degree," as Walter Pater put it,--he never found it necessary to secure this expression at the cost of beauty. That he studied nature at first hand his works are clear evidence, but that did not preclude the choice of attractive subjects. His style is "so sober and contained," writes a recent critic, "so delicate and yet so healthy, so lovely and yet so free from prettiness, so full of sentiment, and devoid of sentimentality, that it is hard to find words for any critical characterization."[2] "Simplicity and nobility," the words of Cavalucci and Molinier, is perhaps the best phrase in which to sum up the art of Luca della Robbia.

In his nephew, Andrea della Robbia, the founder of the school had a successor whose best work is worthy of the master's teaching. If he lacked the simplicity and severity of the older man, he surpassed him in depth of Christian sentiment. Sometimes, it is true, his tenderness verges on weakness, his devoutness on pietism. If we are tempted to charge him with monotony we must remember what pressure was brought upon a man whose works attained such immense popularity. The bambini of the Foundling Hospital and the Meeting of St. Francis and St. Dominick show the high level to which his art could rise.

Antonio Rossellino and Mino da Fiesole may be classed together as sculptors to whom decorative effect was of first importance; they loved line and form for their intrinsic beauty. They delighted in elaborate and well ordered compositions. Elegance of design, delicacy and refinement in handling, are invariable qualities of their work. Such qualities were especially to be desired in the making of those sepulchral monuments which were so numerous in their period. Of the many fine works of this class in Tuscany each of these two sculptors contributed at least one of the best examples.

It is superfluous to point out that the sweetness of these sculptors is perilously near the insipid, their grace too often formal. We are brought to realize the true greatness of the men when we behold the grave and tranquil beauty of the effigy of the Cardinal of Portugal, or the vigorous characterization of the bust of Bishop Salutati.

It is John Addington Symonds who says the final word when he declares that the charm of the works of such men as Mino and Rossellino "can scarcely be defined except by similes." And these are the images which this master of similes calls up to our mind as we contemplate their works: "The innocence of childhood, the melody of a lute or a song bird as distinguished from the music of an orchestra, the rathe tints of early dawn, cheerful light on shallow streams, the serenity of a simple and untainted nature that has never known the world."

[1] Sidney Colvin.

[2] Notes on Vasari's Lives, edited by E. H. and E. W. Blashfield and A. A. Hopkins.

II. ON BOOKS OF REFERENCE.