8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

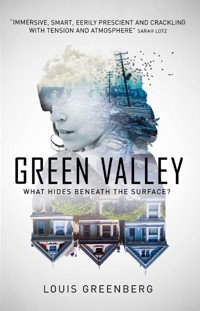

'Immersive, smart, eerily prescient and crackling with tension and atmosphere.' Sarah Lotz, author of Day Three and Day Four Chilling near-future SF for fans of Black Mirror and True Detective. When Lucie Sterling's niece is abducted, she knows it won't be easy to find answers. Stanton is no ordinary city: invasive digital technology has been banned, by public vote. No surveillance state, no shadowy companies holding databases of information on private citizens, no phones tracking their every move. Only one place stays firmly anchored in the bad old ways, in a huge bunker across town: Green Valley, where the inhabitants have retreated into the comfort of full-time virtual reality—personae non gratae to the outside world. And it's inside Green Valley, beyond the ideal virtual world it presents, that Lucie will have to go to find her missing niece.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

I

1

2

3

4

5

II

6

7

8

9

10

11

III

12

13

14

IV

15

16

17

18

V

19

20

VI

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

VII

28

29

30

31

VIII

32

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

GREEN VALLEY

GREEN VALLEY

LOUIS GREENBERG

TITAN BOOKS

Green ValleyPrint edition ISBN: 9781789090239E-book edition ISBN: 9781789090246

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UPwww.titanbooks.com

First edition: June 201910 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2019 Louis Greenberg

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

I

1 ‘Yes, of course she’s here.’ David’s voice was a muffled echo, his impatience degraded to a hazy simulation.

I twisted the tight spiral of the telephone cord around my finger, listening for forgotten inflections to prove to myself that it really was my brother-in-law and not a Zeroth fabrication. I hadn’t spoken to David in eight years, and for many of those years I’d hardly thought about him. ‘When did you last see her?’ I asked. ‘I mean, in reality?’

‘I don’t know. What difference does it make if I saw her physically or not, Lucie? What’s this all about?’

Fabian stepped into the study doorway and gave me a concerned look. I raised my hand and mouthed, It’s okay, then rolled my chair across the floor and toed the door shut on him, the receiver’s spiral cord stretching, the phone dragging with a jangling clatter across the desk behind me.

‘We have information that something’s happening on your side of the wall. In Green Valley,’ I said into the phone. ‘That children are in serious danger.’ If you could call two dead boys ‘information’. I scanned Jordan’s message again. The second, a child of about nine, had been found that very morning in the memorial yard at Hershey Field, bristling with nanotech and Zeroth implants – like the other child, he could only have come from Green Valley. I could have just come right out and told David that children were dying, but it had been a long time, and I wasn’t sure yet how much I could trust him.

‘We?’ he batted back at me. ‘So you’re still with the police. Is this an official call?’

‘It’s not an official call – yet,’ I said, mustering a threat I had no authority to make. ‘I just want to know that Kira’s fine. When did you last see her, in the flesh?’ I repeated.

David clicked his tongue, as if checking on his daughter’s safety was an annoying bind. ‘All right, all right. Maybe in the morning, yesterday. I’m sure I saw her eating something, and then she went on Mathcamp. I can check the logs.’

Whatever David said next faded through flurries of static. I pressed the receiver closer to my ear. You’d have thought Zeroth Corporation, whatever remained of it, could at least still come up with a decent phone connection. Then the static ebbed again and David’s voice sighed through the line: ‘Oh, that’s weird.’

‘What is?’

A pause and a scuffle. ‘Nothing. Don’t worry about it.’

‘David, what’s weird?’

‘It’s just that I can’t… currently –’ a wash of blurring static swirling his words – ‘just a glitch, I’m sure.’

I noticed Fabian’s shadow shifting protectively in the strip of light under the door. ‘I want to see her. I want to come in. Now,’ I murmured, my voice low into the mouthpiece.

‘Into Green Valley? You can’t,’ he said slowly and carefully, as if explaining to a child, as if I was the one who’d lost my mind. ‘Green Valley is a quarantined enclave. You can’t just drop in for a visit. Those are the terms of the agreement you people forced on us.’

‘Bullshit,’ I hissed. ‘There are supplies, there’ve been contractors in and out since you closed. I know you can get me a visitor’s pass.’ Fabian had retreated to the kitchen; I heard him ratcheting the coffee maker – but still I kept my voice down.

‘Yeah, and why would I?’ David said.

‘Because I want to see Kira – today. That’s why. Or would you prefer to wait for a warrant?’

‘You and I both know that won’t happen.’

‘Are you sure?’ I said. ‘Any judge would rule that child endangerment counts as “exceptional circumstances”.’ The threat sounded unconvincing, even to me: the vague ‘exceptional circumstances’ clause stipulated in the Green Valley Partition Treaty of 2020 had never once been invoked in the eight years of its existence. Stanton and US law enforcement had turned a blind eye to Green Valley since the partition.

‘Child endangerment? Really, Lucie? An online math course?’ He sighed again. He clearly didn’t accept that Kira was in any danger. He was either unaware of the children missing from Green Valley, utterly deluded, or lying very well. Or maybe he just thought it had nothing to do with him or Kira. ‘All right. If only to get you off my back. I can do that. I’m important here,’ he added, to my surprise – David having to convince himself of his powers? That was something new. ‘Come to the liaison office. I’ll tell them to expect you.’

I hung up, then dialled the office to call in sick.

Barbra Reeve sniffed me out immediately. ‘You don’t sound sick to me.’

‘I’ve got a family situation,’ I said.

‘With whom?’

I bristled. It was the imperious way she asked, and the fact that as director of Sentinel she knew all my secrets anyway. It didn’t take a spy to figure out that I didn’t have much family to speak of – my only sister dead, my mother gone soon after, a father who never even made the picture. There was no point in lying. ‘My brother-in-law.’

‘The one who lives in Green Valley?’

My only brother-in-law, as you are well aware. ‘That’s right. He invited me in.’ I wasn’t going to let her put me off.

But that wasn’t her intent. ‘That’s bloody marvellous, Lucie. Come and see me first.’

* * *

‘Don’t go to Green Valley.’ Fabian advanced on me the instant I came out of the study, unashamed of listening in. ‘You know what it is.’

‘I don’t. Not really,’ I said.

‘You know what it isn’t,’ he insisted. ‘It’s not real.’

‘Those are lazy Omega catchphrases, Fabe. Of course it’s real. Flesh and blood people living inside a great big warehouse because of a vote.’ A stupid, misguided vote, I wanted to say, but that would have started an argument I couldn’t finish right now. Fabian, after all, was one of the people who had brought the vote about, campaigned against the abuses and invasions of the ‘digital tyranny’. Twelve years ago, his beloved Omega group had stuck a stake through the heart of the global surveillance economy right here in ‘Silicon Stanton’, one of the first in a series of mini-revolutions across the world.

‘They’re the ones who chose to wall themselves in and live in that fake place,’ Fabian said. ‘They could have set aside their tech like the rest of us and lived an ethical, socially responsible life.’

‘Not everybody had a choice, Fabe.’ Before he could stop to think about that, I added, ‘Anyway, I have to go. Somebody needs my help.’

‘It’s David Coady who needs your help, isn’t it?’ Fabian trailed me into our bedroom and looked out at the wind and the glowering sky outside.

When I didn’t respond, Fabian prodded for a reaction. ‘Yes, David. I heard you talking to him. I can’t believe you want anything to do with him. Chief evangelist for that… that mass-surveillance cult.’

His patrician profile silhouetted against the stylish elegance of his flat, framed by his neat white shelves of dust-coiffed revolutionary texts, the righteous certitude painting his face, made me feel as safe as it had when we’d first met. It was hard to believe he still knew so little about me.

‘Trust me, Fabe. You don’t have to worry about David. Zeroth doesn’t have the power they did, and they’re not getting it back.’

‘I’m not worried about him. I’m worried for you. You don’t know what it’s like in there.’

‘And you do?’

‘No, of course not, but—’

‘Well, then. Aren’t you interested? You’ve spent all these years fighting the idea of Green Valley, of Zeroth, but you don’t even want to know what they’ve become.’

‘I don’t believe they can become anything other than what they always were: a malicious virus in society.’ He scraped the hair away from his brow, agitated, his heavy wristwatch jangling. ‘During the Turn, we saw them for what they were, Zeroth and the rest of them. I don’t even know why we conceded so much in the treaty. They should have all been prosecuted.’

Fabian hated Green Valley, where it came from and what it stood for: digital surveillance and control, abuse of privacy rights, organised repression of dissent, complicity and conspiracy. Before we’d met, Fabian had been a key funder and abettor of Omega’s work, a central mind in its think-tank. The remnants of Green Valley’s dangerous vision were what he, the party backed by Omega’s might, and the whole post-Turn political establishment spent their days fighting. They were adamant that they would never allow that abusive cabal to rise again under their watch. But my methods, working for Sentinel… If he knew how I really spent my days, that I spied on Zeroth and Green Valley through illicit electronic screens, he’d see me as the enemy, no better than Zeroth, even though we shared the same target.

What I told Fabian about my work wasn’t all a lie, I comforted myself. Fabian knew half the truth. Make it two-thirds. He knew I worked for the police as a consultant analyst. But he thought what I consulted on was cold-case management and analogue data-handling structures, which is what I’d originally been employed to do. In the past two years, though, my work had diversified into the Sentinel project, and that was the part Fabian couldn’t know about. The secret was poisoning the air between us.

‘You conceded so much because you were desperate to make them disappear,’ I said at length. ‘So that’s how it stands: they own the land and they’re not doing anything wrong.’

‘That we know of.’

‘Well, this is my opportunity to have a look and report back. Don’t you want to check your assumptions?’

‘Of course, but I don’t see why you have to go there. It could be dangerous.’

‘Jesus, Fabe, we can talk around and around this, but I need to go.’

As I grabbed a jacket from the closet and zipped it up, he spoke to my back. ‘Who’s Kira?’

‘Kira’s my niece. Odille had a daughter.’

I closed the door on his questions.

2 I hurried to the station to see Barbra Reeve and came down the steps twenty minutes later, my mind whirling through everything I’d learned about Green Valley over the past couple of years. Intelligence blind spots, the enclave’s hardwiring, delivery and waste management systems, the logistics of their communications systems, what someone could bring in with them, and what, if anything, they could possibly smuggle out. After years of painstaking effort, Sentinel was one tranche of hardwired code away from activating a total tap on their information systems. Reeve had been planning a risky incursion into Green Valley to find the right component, but now I’d been issued with an invitation through the front door. Barbra Reeve could barely conceal her excitement as she delivered her instructions and the extraction kit.

But on the ride out to Green Valley, my mind went to Kira. Why had I never told Fabian about her? I guess she felt like an echo from another life, when Odille was still alive, living with her perfect husband and her perfect baby in her perfect house in Green Valley. But then she died – cancer crashing the perfection party and leaving David alone with a ten-month-old baby girl just as the Partition Treaty was signed and Green Valley was sealed off. At first, I was torn at being so suddenly separated from Kira, my last living connection to my sister – but I had no choice, just like the other families who’d been split by the terms of that urgently expedited treaty.

As time went by, I reconciled myself to the loss, convinced that Kira was fine in there. Despite the Turn, so many people secretly wished they could be inside – this was Green Valley, after all, so much safer and healthier than the real world: Reality 2.0, with its cutting-edge circadian lighting systems, far safer and more nourishing than our carcinogenic sunlight; taintless hydroponic food and natural vitamin blends for optimal nutrition, which was so much more efficient and environment-friendly than common farming; all underpinned by their humanely intelligent integral VR system, which many people still privately envied.

I had allowed thoughts of Kira to fade away with my grief for Odille, confident that she was growing up pampered, happy and safe. Until a couple of hours ago, at least.

‘You sure you don’t want me to wait?’ the taxi driver asked as I stepped out. ‘For if you don’t make your meeting.’

‘Thanks, no,’ I said, handing him a large tip. His was the fourth cab I’d stopped outside the precinct, and the first prepared to come out here. The driver nodded and pulled off, and I watched his yellow car down the deserted road back to Stanton, dwarfed beside the concrete wall. It wasn’t the first time I’d been close to the wall, but I was shocked again by its massiveness, rising starkly to where the concrete roof met it in a seamless curve thirty-two metres up.

Breeze-blown litter scurried on the tarmac; the taxi had disappeared and I’d been staring at empty space. Debilitating panic would not help Kira, I knew: I had to snap out of it and do something.

To my left lay the boarded-up shops, the abandoned houses and the derelict park in what we’d come to think of as the exclusion zone. It had once been the peri-rural edge of a middle-class commuter suburb overlooking Zeroth Corporation’s lush campus, but the concrete wall – fast-tracked extraordinary planning permission paid for from Zeroth’s still-substantial war chest – meant that life in Stanton started a few streets further away now, cringing away from Green Valley.

The air in the wall’s shadow was frigid and stagnant. There was nothing alive here, no evidence even of birds or rats. I could see only two or three rushed graffiti tags on the concrete expanse that should have been an ideal palette for blazers across the city. Those skittish scrawls spoke less of the kids who’d sprayed them than of the unseen ghosts that had chased them away. From what we knew, not even homeless squatters had risked taking up residence in those free houses. The shadow of the wall was a curse.

Shivering myself deeper into my thin jacket, I hitched my backpack higher on my shoulder and crossed to the door set insignificantly into the concrete.

* * *

It was a small door, a reinforced glass door like any street-front office, labelled in Zeroth’s distinctive lettering that you used to see everywhere: Green Valley External Liaison Reception. As if it wasn’t a gigantic tomb I was checking myself into, as if it was a simple, everyday business transaction. I had to remind myself that Zeroth was still a legitimate business, as far as it went. No matter how they had metastasised in Stantonites’ imaginations, Zeroth remained a software and communications company, with people living in a swathe of land they legitimately occupied in a legally formed independent enclave, no matter how idiosyncratically built on. Stanton and the rest of the country had their fair share of huge, covered shopping malls, hotels and office parks, so why should Green Valley feel any different? Choosing to live inside a concrete dome didn’t automatically make you a criminal or a zombie or a vampire.

Stop thinking, I told myself, pressing the button for the bell.

After a few seconds, the magnetic lock buzzed and the door clicked open. I pushed through into the office’s reception area and a fug of incense-saturated air. There was the curved plywood desk I’d been expecting, a fading fitted carpet patterned in Zeroth’s eye icon in corporate lime green against a calming sky blue, but rather than an office, it felt like I’d just entered someone’s living room. A mismatched cluster of framed photographs lined the countertop, and the board-mounted Zeroth posters – Zeroth: better than first – on the walls had been draped with bright fabric hangings that looked like they were from Colombia or Bolivia. A loop of plastic Christmas lights in the shape of flamingos had been strung from one corner of a vacant television screen across the wall to the edge of a filing cabinet, which was topped with a fire-coloured batik cloth and a Japanese vase of plastic orchids.

I glanced behind me, towards the door, checking I was in the right place, but the sign was still clear enough. It was only now that I noticed a woman in blue jeans and bare feet and a tailored pink sweat top sitting on one of the couches, which was also upholstered in faded corporate blue and green, but layered over with throws and crocheted blankets. She was sipping from a pink plastic cup and looked at me with an open face.

Nodding at her, I went to the desk, looking for a bell on the countertop. Behind me, the woman on the couch siphoned the dregs of her drink noisily and after a moment said, ‘With you now.’ I turned to see her stretching as if she’d just been sleeping, and then she padded around to the end of the counter. She walked with confidence, elegantly languid. She had very pretty feet, brightly painted toenails. Her hair was smartly tinted and her skin smooth and healthy; she may have been around forty-five, I guessed, from the lines at her eyes, but looked younger. ‘Let’s see,’ she said, turning on the bulky computer at the desk, something that reminded me of my childhood.

As the computer started up, she looked me in the eyes and I immediately recognised a professional assessment in her glance; her eyes skittered over the ID points on my face, noting the angles and the ratios, ready to compare me to my photograph that she’d have on file.

‘We were expecting someone today. Wasn’t sure what time. You must be the someone.’

‘Yes, I’m Lucie Sterling,’ I said, and held out my hand.

She shook my hand firmly, holding my gaze with green eyes. ‘Gina Orban, external liaison.’ She glanced down at the screen and tapped a few buttons. She raised her eyebrows as she read the information in front of her. ‘Family, huh? Are you David Coady’s sister? None of my business, I suppose.’

‘Sister-in-law,’ I said.

Gina Orban frowned. ‘Oh, so you’re Eloise Parsons’ sister. She’s an interesting person.’

Eloise? Did that mean David was remarried? I did my best to swallow the surprise – did people even do things like marriage in here? ‘Oh, no. My sister was…’ I hesitated.

‘None of my business. It’s not often we get visitors, so I’m asking too many questions.’

‘How often do you process people out?’ I asked as casually as possible, just an interested tourist.

‘You mean Valley people going outside?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Never. None of them leave.’

‘Oh.’ Even though I knew it in theory, the extent of their confinement was a disconcerting thought, especially here, up close. Sentinel had watched the liaison office ever since the partition and the footage backed Gina up: there were very few visitors from outside, and it was only ever them who came out. The children hadn’t come through this office, we were certain, and the only other exit that we knew of was the supply bay.

She took a long-sighted squint back at the screen and raised her brow. ‘Personal authorisation from a subwizard, no less. Makes sense, I suppose.’

‘What’s a subwizard?’

‘Oh, you know. It’s tech speak. They were all little boys when they invented this. I guess they thought calling themselves wizards was more rad than calling themselves kings or gods or whatever. Mr Coady’s what normal people might call a community leader. Or was. I’m not sure. I don’t keep up.’

Her tone – irreverent, disobedient, disloyal? An attitude I wasn’t expecting in the front office of what we on the outside essentially viewed as a doctrinaire cult – put me off guard. I held my tongue.

‘Anyway,’ Gina Orban said, padding out from behind the desk again, ‘are you aware of the procedure? Have you been in before?’

‘No.’ She knew I hadn’t. Not even before the partition. Odille and David would always come and visit Mom and me in the city. Mom was already housebound by then.

‘We need to fit you with The I. I’m not sure how much you know about it, but it’s a complicated system and quite a rigmarole to install, so it’s particularly unusual to grant a short-term entry clearance like this. People don’t just drop in to Green Valley for tea. I’m guessing the visit is important.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘It is.’

‘It’s none of my business. I’m just curious. Not much comes through this office.’ I couldn’t tell whether she meant information, goods or people, or what.

I was eager to get into Green Valley, but didn’t want to be curt. Any information this casual and evidently lonely officer might let slip could be useful. ‘I don’t mind,’ I said. ‘What do I need to do?’

She led me to one of three doors at the far end of the reception room. ‘I’ll need you to take off everything you’re wearing and put it in one of the lockers, along with any devices, currency, contact lenses, jewellery, baggage, electronics, everything but your natural self you were born with. Cover yourself with the towel in the locker and let me know when you’re ready and we’ll begin.’

She said it so neutrally, it was almost like I was being asked to check into a spa, or an abattoir. I objected, ‘From what I knew of it before you… before Zeroth sealed, The I was a device you wore in one eye and it acted like a sort of personal computer screen. I’m not sure why you’re asking me to…’

She smiled at this, a waxen smile that only affected her lips and left the rest of her face frigid. ‘“Personal computer screen,”’ she mocked. ‘Wizard Whitebeard wouldn’t be pleased to hear his visionary work reduced to a “sort of personal computer screen”. Anyhow, it’s evolved. It’s how Green Valley functions, in its entirety. It is Green Valley, really. To be in Green Valley, you need The I. And The I’s evolved since the Turn.’

I tried to look politely surprised. I knew the technology was still being developed behind these walls; at Sentinel, I’d been analysing intelligence that suggested it, but I didn’t see all the information, and there was no one analyst who understood it fully. Anyway, I didn’t have to understand how it worked to use it, I told myself, repeating that complacent phrase that was almost blasphemous after the Turn. It had been such a comforting line to take back then, absolving ourselves of all responsibility, dropping our fates into the hands of seductive strangers, corporate entities in whose benignity we could feasibly believe.

Gina noticed my hesitation. ‘Nobody’s forcing you. You don’t have to come in. You could get a message to your brother – your brother-in-law – some other way.’

I took a deep breath. I had work to do. ‘No, of course I want to. David and I have something to discuss, and besides, I’m really interested to see what it’s like.’ Trying to convince myself, too, because my heart had started clawing at my ribcage.

She directed me to the changing room and handed me a small brass bell by its tongue – Tibetan or Persian, I guessed, when I saw the intricate etchings on it. ‘Ring this when you’re ready.’

* * *

Like the reception, the changing room’s institutional edges had been softened by domestic touches. The stand of four metal lockers had been painted in pastel tones – mint, lilac, peach and sky blue – and detailed with hippie flowers. The slatted wooden bench was covered with Arabian cushions, while the row of basins was ornamented by candles, one of them alight, bottles of scented hand creams and liquid soaps. A hand-scripted card was pasted to the broad mirror above the basins with a platitude that sounded somehow menacing: What You See Behind You Is Not What Lies Ahead.

I chose the peach-coloured locker. The rusty hinges scraped as I pulled it open and I wondered just how few people came through here, and just how bored Gina Orban was, and what sort of thing extended boredom might do to a person’s mind. Hand-painted daisies beamed at me as I pulled myself free of my turtleneck, but when I started on the button of my trousers darkness flashed in my peripheral vision. I whirled around and saw myself in the mirror, only me, but still that shadow was settling somewhere in this room. The candle’s flame danced and tugged as if something had hurried past it.

It’s just me, I said to myself. There’s nobody else here. But still, I went to the mirror, looking into it, my face pressed close, cupping my hand between my brow and the glass to check that someone wasn’t watching me from the other side. When I was pretty sure there were only the white tiles and the wall behind the mirror, I quickly stripped down to my underwear and reached for the large towel, which let off a small plume of stagnant white cotton dust as I unfolded it. The towel had probably never been used, but it had sat here for a long time. After shaking the towel out and wrapping it around me, I put my things into the locker, then rang the bell.

‘You’ll have to take that off, too,’ Gina said when she came in, barely glancing at me, but noticing my bra straps. ‘I’ve really seen it all,’ she said.

Reluctantly, I unhooked my bra and dropped my underwear. This was the price I had to pay to get into Green Valley, I reminded myself, but it was already rising higher than I was comfortable with.

Gina hooked a hanger with a green-trimmed blue tracksuit on the locker and placed an unused pair of trainers below them. ‘As soon as you’re fitted, you can wear this when you go in. Hardly the height of fashion, but it doesn’t matter in there. They won’t be seeing you; they’ll be seeing your avatar. Same goes for everything you see in there. You’ll be walking around a real place, of course, and talking to real people, mostly, but you’ll be seeing, feeling, tasting it in its enhanced state, as The I sees it. Sunshine, singing birds, unicorns, the works. In Green Valley, the virtual is reality. Or so I’m told.’ She took a tablet screen out of a small cabinet beside the lockers and slid her finger over it, then turned the screen to me where a photograph of a woman appeared. She was of medium build and medium height, wore blue slacks and a white blouse, low-heeled shoes and had unadorned shoulder-length blonde hair. She had a symmetrical face with full lips and a small nose, and slightly larger than normal eyes.

‘Who’s she?’ I asked.

‘That’s you.’

‘Me?’ I said, knowing what she meant, but demanding that she explain it as if I didn’t. It was the principle: you shouldn’t nonchalantly get away with giving someone a new body without comment.

‘That’s your avatar. It’s how people will see you in Green Valley. You’d be very welcome to customise her, but we’re running low on time.’

‘It’s really fine,’ I said. ‘It doesn’t matter to me at all.’ It did, though. Still, I was titillated by the idea of being this fantasy blonde for a day. I wondered if people would treat me differently.

‘I call her Plain Jane,’ Gina said. ‘But to be honest, I wouldn’t mind having her bone structure and her model face and her defiant boobs. The wizards designed her, of course.’

Again, it was hard to ignore the sarcasm dripping from her words, the undisguised resentment; referring to Jamie Egus as ‘Wizard Whitebeard’. She was inviting me to probe. ‘Tell me, Gina,’ I said. ‘Why are you here? You don’t seem to… fully buy into the Zeroth ethos.’

She laughed: a hoarse, empty rattle like an echo in an abandoned house. ‘Lie flat on your stomach and let me start.’

I did as she said. She knelt down next to me and zipped open a soft briefcase. ‘You could call me uniquely cynical, I suppose,’ she started. ‘About Green Valley, and about Stanton. I don’t belong to either of them.’ As she spoke, she folded the towel up and rubbed a cold liquid over the small of my back. ‘I used to be an occupational therapist on Zeroth’s staff in the heyday, before the Turn. When they were developing The I, I was offered an alpha trial. I suffered some of the worst recorded cases of motion sickness and aversion, so impressive that they made me the development team’s guinea pig. Voluntary, of course. They would never have forced me, but they paid me extremely well. At that time, they were launching simple virtual reality interfaces to the public – enhanced social networking, collaborative gaming, mindfucking porno experiences, you know. But half the potential clients got nauseous, puking on their POV sexbots and their dragon joust opponents rather than having fun.’ She rubbed the ointment up my spine, making it tingle, scratching or drawing something on my neck and then pinning patches of hair back on my head. ‘They suffered from what they call the uncanny valley effect,’ she continued, ‘suffering fight-or-flight panic attacks in the middle of virtual tropical holidays. Everything looked too real, but their cerebral cortices knew that it was all an illusion. On a primitive, instinctive, cellular level, the parts of their brains that hadn’t been fooled were screaming out that they were being tricked, that they were in mortal danger. This was obviously not good for business, not good for uptake of the new devices. Development figured if they could beat the symptoms in me, they’d beat it in ninety-nine per cent of cases and that would be good enough. It worked out well. I’m one of the guinea pigs who led to Zeroth’s VR dominance. It left me with certain… side effects… but they’ve been good to me, and I have a peaceful existence here.’

Then Gina rammed a spike into my lower back. I wanted to scream with pain, but then I realised there was no pain. A cold ripple rushed out from the spot and zapped through my spine in an electric rush. I bucked and arched with the pulse, and then it was gone. I groaned. ‘What the fuck was that?’

‘Sorry. A little discomfort, but that’s the lumbar transponder.’

Before I could ask any more, she’d stuck something into the base of my neck that paralysed me. That same seismic cold ripple, but this time either I couldn’t move my body to accommodate it or I couldn’t feel my body arching. I was vaguely aware of cushions scattering off the bench, Gina’s hands replacing them, a sense of better comfort, the mortification of seeing my bundled underpants crumpled under the bench. If I die here… I thought distantly. Claws pushed between my follicles, hooking my head, without physical pain but with the instinctive substrate of pain. My body screamed for me to move, to run, but I was paralysed and, to be honest, feeling all right, not bad at all, and I didn’t know what I was panicking about. I should just relax. And all the while, I was looking at the bundled pants and thinking of how I’d lie on my bed as a girl, rubbish strewn all around me, protected by the tinny clatter of my headphones, safe and soft and warm.

And then a gasp and a crash and a spike through all my veins and I realised I was lying naked on the bench and Gina’s warm hand was flat and calming on my back. ‘Okay,’ she was saying. ‘Ten seconds to calibrate. Hang in there.’ Rubbing my back with her warm, soft hand like a mother should when her child cries. ‘Got you. How’s that?’

At length, I was able to turn my head and see Gina looking at the tablet screen. I turned my head the other way, tested my limbs. Apart from a small added weight on my lower back and in my neck, a tug of trapped hair when I moved, it was okay. I reached down for the towel, which was half covering me again, and pulled it up my back. ‘Is that it? Can I get dressed?’

‘Sure. Give it a minute, then try to stand. If your balance is out, we’ll fine-tune.’

I pushed up to sitting, tightening the towel around me. I should have felt violated and angry, although this woman had only done what I’d asked her, and she had such soft, sympathetic hands and I couldn’t be angry even when I tried. And then I did try. I thought of those things that always made me angry – catcallers, bullies, cold-callers, power cuts – but the emotion shot by me like an express train through a station, and then it was gone. I tried to feel angry about the fact that some device was controlling my mind, but I couldn’t, so I tried fear. I thought of a group of drunken men on a quiet road, the sound of a wolf-whistle in the middle of the night. Briefly my adrenaline surged, but before I could catch the feeling it dissolved. Outrage, shame – gone. I tried to find it funny. I tried to laugh, but the sound died on my lips.

‘We put guests into full SSRI mode. Especially short-term. There’s no time for you to adapt to the environment, so we essentially balance your emotions by controlling your serotonin and dopamine levels with nanorobots. It may seem a little strange, I guess. But I’ve heard it’s pretty calming, too. It’s an electronic opiate. Do you like it?’

‘I don’t want to,’ I said, managing to stand. I hadn’t intended to be so honest with her, but I’d been somehow compelled.

‘Good. Your balance is great.’ Gina looked away, discreetly arranging her kit in her case as I changed into the tracksuit. I remembered to fold my underwear and placed it on the shelf in the locker, checking at the same time that the tight package I’d brought remained tightly tucked where I’d left it, in the inner pocket of my coat. ‘Now comes a part some have found pretty nasty, I’m afraid. I’m sorry for it, but it’s essential: we need to check your aversion levels. Come, sit comfortably.’

‘Aversion levels?’

Gina came to sit beside me, the tablet screen in her hand displaying a series of dials. ‘At first, when people came to visit Green Valley, they’d want to quit out manually. Maybe they had motion sickness, maybe the experience was overwhelming – who knows, maybe it was boring them. But some of them, despite all the advice to port out correctly, here and only here, saw fit to try to unplug The I and rip the interface off themselves. Let’s just say the results were not good. “Suboptimal” in Development’s terms. They needed to find a way to prevent this. Using the physiology behind the cortical aversion that users like me experienced when faced with the virtual world, they developed an aversion signal that would fire any time the system was tampered with. It would render a visitor physiologically unable to remove the rig, anywhere except here.’

‘Like an electronic dog collar?’ I said, acutely aware that my body had been attached to a dangerous electronic circuit. ‘The one that zaps the dog when it strays over the boundary?’

‘Yes.’ Gina raised her lips in that cold version of a smile. ‘Something like that.’ And without warning, she tried to kill me.

It started as a quiver somewhere deep in the lower part of my head, deeper than my head should go. Something – lots of somethings – were running through tunnels dug into my brain. They were running in mortal dread. And the closer they got to me, to the sensing part of me, over their vague blurring terror-coloured shoulders I could feel what they were running from and it was all I had ever feared and all that these thousands of fleeing shadows had ever feared bundled up into a mass like a fist that was coming so fast it was going to shatter me as it hit and before I could scream it was in me and I was flying in a thousand shards and each of them burning with an acid of fear and I needed to scour—

But then it sucked back into itself like the vacuum of space eating an explosion.