Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

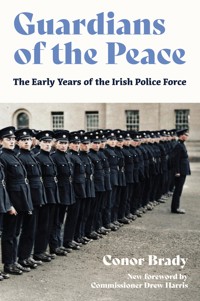

Guardians of the Peace is a political history of the Irish police force, An Garda Síochana, from its foundation at the birth of the Irish State, through the Irish Civil War, the threat of the fascist 'Blueshirts', the continuing campaign of the IRA, de Valera's entry into the Dáil in 1932 and the creation, effectively of his own police force – 'The Broy Harriers' – through World War 2. As the author outlines in his insightful introduction, the story told in this book is part of a longer and wider narrative. But it is a story which still has relevance as Ireland moves, hopefully, to a new era of peace and stability. It is above all a chronicle of the idealism and the imperfections of ordinary men presented by history with the discharging of a rather extraordinary task. As the force approaches one hundred years since its founding, it is hoped that this history will evoke the ideals and the founding principles adopted in 1922 and perhaps help to re-interpret and re-apply them in a 21st Century context.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 462

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Conor Brady is former editor of The Irish Times and former member of the Garda Ombudsman Commission. He is an Honorary Professor of Journalism at NUI Galway and is chair of the Top Level Appointments Committee. He is the author of numerous books, both non-fiction and fiction.

GUARDIANS OF THE PEACE

First published in 1974 by Gill and Macmillan, this edition published in 2022 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Conor Brady, 1974, 2022

Foreword © Drew Harris, 2022

The right of Conor Brady to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-841-8

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-842-5

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and obtain permission to reproduce the photographs in this book. Please do get in touch with any enquiries or any information relating to these images or the rights holder.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

For my wife, Ann

ALSO BY CONOR BRADY

The Guarding of Ireland

The Garda Síochána and the Irish State 1960–2014

CONTENTS

Foreword by Commissioner Drew Harris

Introduction

1The Irish Garrison 1812–1913

2The Chaos of Transition 1913–22

3Steps Towards Order 1922

4From Mutiny to Civil War 1922

5O’Duffy Leads the Guards

6The Security of the State 1922–23

7The People’s Peace 1923–25

8The Birth of the Special Branch

9Special Branch Versus IRA 1925–32

10A New President and a New Commissioner 1932–33

11The Broy Harriers 1933

12Guards Versus Blueshirts 1933–35

13The Guards at War 1935–45

Epilogue, 2022

Sources

Interviews and Acknowledgements

Bibliography

FOREWORD

Commissioner Drew Harris

As the Garda Síochána marks the centenary of its foundation in 1922, it is timely and appropriate that Conor Brady’s Guardians of the Peace, telling the story of the service’s formation and the struggles of its early years, should be re-published by New Island Books.

As Commissioner (the twenty-first person to hold this post since the foundation of the State) I welcome the opportunity provided by this publication to revisit the achievements of the early generations of gardaí and to reflect on the values and principles upon which the organisation has operated in its 100 years of service to people of Ireland.

Social, economic and political circumstances in twenty-first-century Ireland are profoundly different from those in 1922. The task of policing has become more complex and multi-faceted. Technology has changed almost every aspect of police work, as it has changed so much right across society. The community’s expectations, both of the police as a public service and of the individual police officer, are more demanding. Rightly, there is a greater emphasis on transparency and accountability in the way that police officers discharge their responsibilities.

But the personal qualities demanded of the police officer and the underlying values that inform his or her work are constant. Just as the founding members needed qualities of courage, judgement, fairness and integrity, so too do the Gardaí of the twenty-first century. The founding gardaí had to be independent of politics and loyal to their duty under the law, regardless of whatever pressures might be presented. They had to have a sense of patriotism and a deep awareness of their special place and their special responsibilities to the community. So too, do their successors in office in the twenty-first century.

The service’s very name – and the title of this book – evoke the essence of what the Garda Síochána has been about since its foundation. Its role is to preserve the people’s peace, to prevent the visitation of crime and violence upon the citizen and to protect and guard all citizens while vindicating their rights in their day-to-day lives. Its record in achieving these aims is impressive. Where, on occasion, as with every man-made institution, it may have fallen short, it has endeavoured with honesty and with energy to make good.

Above all – and this theme runs through the narrative of Guardians of the Peace – from its inception, the Garda Síochána has been a police service that is rooted in the community and that exercises its policing functions with the community’s consent. As my first predecessor in office, Commissioner Michael Staines, told the early members, the force was to succeed, ‘not by force of arms or numbers but by their moral authority as servants of the people’.

The author is well placed to tell the story of the Garda Síochána. He was editor of The Garda Review from 1973 to 1975 and later wrote extensively for The Irish Times on policing and security matters. In 2006 he was appointed by the President of Ireland, with the approval of the government and the Houses of the Oireachtas, to serve as a founding commissioner of the Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission. He served as a member of the Commission on the Future of Policing which reported to government in September 2018. His late father, Superintendent Cornelius Brady, was a founding member of the service.

As he writes in his introduction, the story of the early decades of the Garda Síochána is that of ordinary men doing an extraordinary job. They earned their place in the history of the Irish State with distinction and members of the Garda Síochána today continue to serve their station with great distinction.

INTRODUCTION

Perhaps one of the most instructive tests of a democracy is the way its police services operate. In their relationship with the community, in their accountability, in their operations and in their overall conduct, the police are almost invariably a mirror-image of the broad values of the society they serve. In few countries is this as true as in the Republic of Ireland.

When this account of the foundation of the Garda Síochána was first published by Gill & Macmillan in 1974, the force was little more than fifty years old. When the second edition, undertaken by Prendiville Publishing, appeared in 2000, it was emerging from a period of more than thirty years in which it had been primarily operating to deal with the violence that flowed from ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland. With this publication by New Island Books, it is marking its centenary in supposedly peace-time conditions. Yet the challenges facing it and the expectations of the community it serves have never been greater.

It is hoped that this latest publication, coinciding with the centenary of the force’s establishment, can serve to evoke the ideals and the founding principles adopted in 1922 and perhaps help to re-interpret and re-apply them in a twenty-first century context. The force was proclaimed by its early Commissioners to be the servants of the Irish people. Its values were to be the values of the community. Its loyalty would be to the State and it would be accountable to the democratically elected government of the State. After a brief period during the Civil War when it was envisaged as an armed force, it was to be routinely unarmed. It would succeed, Commissioner Michael Staines declared, ‘not by force of arms or numbers but on its moral authority as the servants of the people’.

The Garda Síochána, originally and briefly known as the Civic Guard, was to have certain unique characteristics that marked it out from other police forces. Policing in Britain was organised on a county basis but the Garda Síochána was to be a national force, covering all twenty-six counties of the new State. Most European countries have a number of layers of policing at local, regional and national level. The Irish Free State was to have no such arrangements. Perhaps most significantly of all, the Garda Síochána was to discharge both the functions of a civil police force and those of a national security service. This remains the situation today, conferring a role on the force that is unique in western policing systems.

The establishment of a new police force along these novel lines, in the immediate aftermath of a bitter civil war, was to test the discipline, the endurance and sometimes the courage of the several thousands of young men who had the task of making it a reality on the ground.

This book was originally written at a time when some of the political figures who were involved in the foundation the force were still living, as were quite a few of its founding members. Its purpose was to record their account of one of the most enduring enterprises of independent Ireland and to place it in a political, historical and social context. In the half century since the original publication of Guardians of the Peace, all of the founding members of the Garda Síochána who assisted me in my undertaking have passed on. When I began my research in the early 1970s, I realised it was important to get their accounts at first hand before the march of time would make it impossible. Few archival sources were open to me and in the main I relied for documentary support on a small store of private papers and official documents – Routine Orders, for example, or published material such as The Garda Review; the Garda pensioners’ magazine, An Síothadóir or the Garda Síochána Code. The Mulcahy papers in the archives of University College Dublin and some papers provided by the late Mr Ernest Blythe gave me an insight into government thinking. Some former members of the force allowed me access to personal diaries or written accounts of particular events.

In the intervening period, new sources have opened up. State papers have been made available with the passage of time and many valuable documents have been turned over to the Garda Museum, which did not exist fifty years ago. Moreover, there has been extensive and valuable scholarship into the history of Irish policing. In short, a great deal more is now known about the establishment and development of Ireland’s national police force than when I finished my work in 1973.

The option has therefore existed of revising Guardians of the Peace in the light of all that has been learned since and to amend or expand the narrative. In preparing the 2000 edition I decided not to do so but to allow the original version, with its undoubted imperfections, to stand virtually as it was written. There is one signal exception. It concerns the narrative in Chapter 10 of the supposed preparations by General Eoin O’Duffy to stage a coup d’etat against the incoming Fianna Fáil government. Relying wholly as it did on the information of one witness, this account should have been qualified when first published. The matter was addressed in the 2000 edition.

Guardians of the Peace was scarcely published in 1974 when the power-sharing administration in Northern Ireland, set up under the Sunningdale Agreement, collapsed. Northern Ireland faced into more than twenty years of violence and the course of events for the whole island was changed. Policing, North and South, was to undergo extraordinary change as well. Although the Garda Síochána did not face unrestrained paramilitary violence as the Royal Ulster Constabulary did; gardaí were still obliged to engage with the rise of politically inspired violence. Some died, while many others were wounded. The development of the force for the next twenty-five years was shaped almost wholly by the security requirements which flowed from the Northern Ireland crisis.

Contemporaneously with the crisis of the North, the pace of social and economic change quickened within the Republic of Ireland. Rising living standards and a relaxation of social mores were accompanied by a growing crime rate. Armed crime overflowed from the North, and ordinary criminals quickly saw that guns could yield profitable results, making the armed criminal a reality in the cities and towns of the South. As Ireland became more urbanised, international linkages increased. Organised crime grew and developed in the urban areas. The drugs trade in particular came to dominate whole areas of Dublin, Limerick and other cities. The Garda Síochána was facing into a period in which crime would become highly profitable, ruthlessly violent where necessary and organised, in some instances, at business-school levels of efficiency.

In the closing years of the twentieth century, evidence began to emerge confirming what many had long suspected: that Irish society harboured many dark secrets, injustices and inequalities under its patina of religious devotionalism and social conformity. It became clear that crime grew, in considerable measure, from conditions of social deprivation, especially in the larger cities and towns. Extensive problems of sexual abuse of vulnerable children, sometimes at the hands of those into whose care they had been entrusted, came to light. More slowly, but no less surely, it began to become clear that white-collar crime and corruption were widespread within supposedly respectable strata of Irish society and that they reached into the heart of the administrative and political establishments. Successive tribunals of inquiry revealed corruption at the highest levels of the political establishment and at the most senior levels of local administration.

The Garda Síochána of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s found itself obliged to adapt to this increasingly complex society in which traditional assumptions about right and wrong were often inverted. The simplicities and certainties of earlier times were no more. Most of the institutions of authority in Ireland – the political establishment, the churches, big business, the banks, the professions, even the courts – found themselves facing challenges to their credibility and confidence. The Garda Síochána was only one of many institutions obliged to face up to new realities, new demands and new challenges.

Reform and modernisation of the Garda Síochána, however, has been slower and more tortuous than in many other institutions of the State. The lessons that should have been learned from the so-called ‘Kerry Babies’ debacle and other failures of the 1980s were not fully adopted. It was therefore not surprising when, in the 1990s, widespread scandals in policing came to light in the Donegal division. A tribunal of inquiry chaired by former High Court President, Frederick Morris, ominously warned that misconduct of the kind disclosed in Donegal was unlikely to be confined to that division alone.

The recommendations and safeguards called for in the five reports of the Morris Tribunal were honoured more in the breach than the observance and thus, as the twenty-first century opened, the Garda Síochána lagged very far behind other State institutions that were now adapting to very much higher standards of openness, transparency and accountability.

Repeated systems failures, non-disclosures, poor management, indiscipline and, finally, the revelations of whistle-blowers, notably those of Sergeant Maurice McCabe, brought matters to a head, resulting in two major legislative initiatives, the Garda Síochána Act 2005 and the Garda Síochána Act 2015. The 2005 Act created the Garda Síochána Ombudsman, with powers to investigate certain complaints against gardaí; it also provided for the establishment of the Garda Síochána Inspectorate. It transferred responsibility for the Garda budget from the Department of Justice to the Commissioner. The 2015 Act created the Policing Authority to which the force effectively became accountable. It gave the Authority responsibility for promotions from the rank of Superintendent to Deputy Commissioner. In 2017, following the revelation of further systems failures, a Commission on the Future of Policing in Ireland was established by government with US police leader Kathleen O’Toole as chair. Implementing the recommendations of the O’Toole Commission is still a work in progress. When the Commission’s report was published in 2018, the government accepted its findings in full and established an implementation process. This commenced in parallel with the first major restructuring of the Department of Justice since the foundation of the State. The O’Toole recommendations included a realignment of functions between the Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission and the Inspectorate and transferred responsibility for promotions from the Authority to the Commissioner.

One of the most important questions facing the O’Toole Commission was whether the Garda Síochána should continue to have responsibility for both civil policing and national security. In the end it decided that this unique combination of functions, originally decided upon in 1922, should continue. However it also recommended the establishment of a new post within the Department of An Taoiseach to coordinate the security and intelligence functions of the gardaí, the defence forces and other state agencies.

Today’s Garda Síochána is much more highly trained and educated, far better equipped and better managed than when the first edition of this book was published. It is backed with a range of specialised services which were unimaginable a quarter of a century ago. Many key functions within the force are now discharged by suitably qualified, non-sworn personnel. In 2018, Drew Harris, previously Deputy Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, became the first Commissioner to be appointed from outside the force since Daniel Costigan in 1952.

Pay and conditions of service have continued to improve in line with Ireland’s increasing prosperity. And while the ranks of the Garda Síochána are still predominantly male, the numbers of female members have steadily increased. The first female Commissioner, Nóirín O’Sullivan, was appointed in 2014 and served until 2017. Regrettably, the new ethnic minorities among the Irish population remain under-represented in the force although imaginative and successful linkages between gardaí and ethnic minorities have been promoted by garda management.

The Garda Síochána has at times leaped forward to embrace change, as with the establishment and development of the training college at Templemore. At other times it has had to be dragged kicking towards reform. Today, it is undoubtedly more honest about its own shortcomings. As with many other organisations, it has abandoned or broken out of time-honoured conventions. Gardaí have engaged in what is effectively strike action, to the dismay of many of those who would still wish the force to discharge a vocational or exemplar role in Irish society. Yet, when opinion is polled, its standing is still high among the population. Even in a society with a skills shortage and in which young people can pick and choose between attractive careers, entry to the Garda Síochána is highly prized. It is remarkable that Ireland pays its police officers better than its teachers, its nurses and the great majority of its civil servants.

It is now possible to refer the reader to a much more comprehensive bibliography of Irish policing history than in 1974. The narrative set out in Guardians of the Peace has been greatly amplified by a number of works which have been published in recent years and which must be especially recommended. Primary among these are Gregory Allen’s The Garda Síochána (1999); Liam McNiffe’s A History of the Garda Síochána (1997); Eunan O’Halpin’s Defending Ireland (1999); and Dermot P. J. Walsh’s The Irish Police (1998). The Civic Guard Mutiny (2012) by Brian McCarthy is an excellent account of the events in the summer of 1922 that led to the effective disbandment of the first cohort of recruits and the re-launch of the Garda Síochána as an unarmed force.

A number of personal accounts of life in the Garda Síochána have been published, including Tim Doyle’s Peaks and Valleys (1997) and Tim Leahy’s Memoirs of a Garda Superintendent (1996). John D Brewer produced a remarkable oral history of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) while Stephen Ball edited A Policeman’s Ireland (1999) – Recollections of Samuel Waters RIC as part of the Cork University Press’s splendid series Irish Narratives. Jim Herlihy has produced valuable work on the Royal Irish Constabulary and on the Dublin Metropolitan Police, including a complete copy of the RIC list. Donal O’Sullivan, a former Chief Superintendent of the Garda Síochána, produced a fine overview of policing in Ireland between 1822 and 1922 – The Irish Constabularies (1999). There has been extensive work on the history and contemporary conditions of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). Chris Ryder’s The RUC, a Force Under Fire (2000) is essential reading. So too is Sir John Hermon’s Holding the Line (1997). Completeness requires a reading also of John Stalker’s account of his time in Northern Ireland, entitled simply Stalker (1987). A number of former gardaí, both uniformed and detectives, have published memoirs of their work. Quite a few specialised crime reporters working in the media have produced insightful and detailed analyses of Ireland’s criminal underworld. The story told in Guardians of the Peace is part of a longer and wider narrative, but it is a story which still has relevance as Ireland moves, hopefully, to a new era of peace and stability. It is above all a chronicle of the idealism and imperfections of a generation of ordinary men presented by history with the discharging of a rather extraordinary task.

There are many imponderables ahead for policing as Ireland goes through the third decade of the twenty-first century. There may be far-reaching political change as the parties of the centre move away from their Civil War roots. New relationships will emerge between the Republic and Northern Ireland, although the likely shape of those relationships cannot be discerned as of now. It is likely that there will be increasing operational integration between the Garda Síochána and the Police Service of Northern Ireland which replaced the RUC in 2001.

Having been largely defined by the illegal drugs trade, sex-trafficking and smuggling for many years, crime will take new and additional forms which will be largely cyber-based. Social patterns will change, driven primarily by the imperative of tackling the planet’s climate crisis.

The challenges facing the Garda Síochána may bear little apparent relationship to those faced by the men of 1922 and later. But responding to them will require the same qualities of public service, patriotism, patience and sense of duty that had to be mobilised a century ago.

Conor Brady

Galway, 2022.

1THE IRISH GARRISON1812–1913

In a period of just under seven months – from February to August 1922 – the 10,000 men of the Royal Irish Constabulary, the organisation which had formed the backbone of British administration in rural Ireland for over a hundred years, disappeared from the towns and villages where they and their predecessors had enforced the writ of the Crown on four generations of their fellow Irishmen. They made their way in small detachments of ten or twelve, sometimes under the grudging protection of an Irish Republican Army escort party, to the nearest military camp or railway station thence to depart to England or America, the police forces of the colonies or in some cases to Belfast, where the government of Northern Ireland was recruiting a new police force. By the autumn of 1922 the once familiar bottle-green uniform of the ‘Peelers’ America or the police forces had vanished forever from the countryside of twenty-six Irish counties.

In the momentous events of those troubled months the passing of the RIC was scarcely noticed, and generally not regretted, by the people among whom they had lived and worked.

Their inglorious end was understandable, for the force had all but ceased to function in a police role for over two years. Its ranks had been depleted by resignations, its morale had been broken by the success of the Sinn Féin boycott and the IRA guerilla campaign. Above all, its acceptability among the people had been irrevocably lost through the excesses of the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries. And yet nothing symbolised more clearly the changes which were taking place in Ireland than the disbandment of the RIC. It was the end of the force which had embodied British power; the RIC had not only symbolised, but made meaningful with their very presence, the control which Britain had exercised over Ireland and the Irish people. The constabulary had represented the Dublin Castle administration in a host of matters, mainly quite unconnected with police work. They looked after the school attendance regulations, the Weights and Measures Acts, and agricultural statistics; they had a hand in the regulation of virtually every aspect of life in rural Ireland. No farmer, shopkeeper or tradesman could hide anything from the Peelers for it was their duty to know everything about everyone. They were the eyes and ears of the Castle, and where necessary they were its strong right hand. They were, in short, the single, strong and utterly reliable service which had enabled Britain to hold Ireland in a condition of relative tranquillity over the previous hundred years.

The RIC had been a unique institution. It combined the functions of a rural gendarmerie, a civil police and – outside of the larger towns – a rudimentary civil service. Nurtured on classical colonial lines, it had served as a model for policing troublesome subject races of the Empire who could not be left to look after themselves and who could not be left under the permanent care of the army. The basic concept was that of a native force, raised from the sturdier elements of the peasantry and rigorously drilled, trained and officered by Englishmen. Well armed and equipped, they were spread throughout the country in compact, small detachments within easy reach of one another in event of serious disturbance. In slightly varying forms, this model was used for the policing of India, Canada and Africa with considerable success. In Ireland too it was highly effective and proved its worth in suppressing the Fenian risings of 1848 and 1867, while in the earlier decades of the century it had been the Tory government’s sole effective weapon in dealing with the combined evils of agrarian outrage and sectarian strife.

The Royal Irish Constabulary owed its origins to Robert Peel, more celebrated in police history as the founder of the London Metropolitan Police – the legendary Bobbies. The two systems, of necessity, were worlds apart, for Londoners would not have policemen patrolling their streets with carbines slung across their backs and bayonets and revolvers in their belts. But it throws an informative sidelight on the nature of British administration in Ireland in the years immediately after the Union that two entirely different police systems should be developed for a supposedly ‘united’ kingdom. Britain got an unarmed policeman, answerable not to central government but to a watch committee and depending in the last analysis on the moral support of the community to enable him to enforce the law. Ireland, by contrast, got an armed garrison, rigidly disciplined and directly controlled by Dublin Castle, operating with the backing of the Martini-Henry carbine, the bayonet and the sword rather than the support of the community.

In September 1812 Peel arrived in Ireland as Chief Secretary to find the country in the preliminary stages of chaos. There was a mounting toll of violence and destruction all over the country which neither the civil nor military authorities appeared capable of controlling. The militia’s manpower had been drained off in order to cope with the continental wars and the medieval policing system had been entirely overrun by the scale of violence and outrage. Probably most serious of all, the local magistracy system was riddled with abuse and corruption and in the few districts where sufficient organised strength was available to put down crime, there was not always the inclination among the supposed leaders of society.

Ireland was beset by a major threat to public order in the form of secret societies, which had become a dominant feature in the pattern of Irish rural life since the 1760s. These illegal, oath-bound combinations of men were motivated primarily by agrarian grievances, though in the North the basic issues were confused by sectarian differences, frequently fostered by a reactionary ruling class. The political ideologies of French and American republicanism also had a small, but by no means insignificant, influence among urban intellectuals (many of them Ulster Presbyterians) and were largely responsible for the formation of the United Irishmen and the abortive rebellions of 1798 and 1803.

The principal secret societies – the Whiteboys, Rightboys and Ribbonmen – had a membership of many thousand among the lowest stratum of society – the landless labourers and cottiers. The main waves of their activity occurred in periods of greatest economic distress, when high rents, tithes and dues coincided with low wages and potato shortage to cause considerable hardship. In such periods agrarian outrages were common and great areas of the country, particularly the South and South-west, were plunged into disorder. It was frequently necessary to call in special army detachments or ad hoc bodies of militia to control the eruption of violence, and although they were generally successful in armed confrontations or punitive expeditions, they were of little use in a purely preventive capacity.

The outbreak of the Napoleonic War and the subsequent withdrawal of much of the garrison for service in Europe gave an additional sense of urgency to the government’s approach to the problem of secret societies. Although the vast majority of the peasants who participated in rural agitation had little interest in the political ideas of Bonapartism, the timid and isolated Protestant Ascendancy now saw them as a grave menace both to the security of the State and to their own safety. The authorities, whether influenced by these exaggerated fears or by more sinister motives, kept alive the illusion of a nationwide conspiracy to bring about a French invasion in which the Grande Armée would be joined by the insurgent hordes of Catholic Irish, all intent on a final massacre of their hated masters. But even if the secret societies were misrepresented, their activities continued to have a severely disruptive effect throughout the country.

To cope with this dangerous situation on behalf of the Crown, Peel found at his disposal an antiquated police system which had carried over without improvement since the Middle Ages, a magistracy which was largely corrupt and inactive and a military garrison which had been reduced to a fraction of its original strength and effectiveness.

The basis of policing in rural Ireland up to this time had been a combined use of the military and the rather generously entitled ‘Baronial Police’. The ‘Barnies’ as they were more commonly known, were, in the main, deserving pensioners who were appointed by the local magistrates through the County Grand Juries. Pay was very poor and there was no training or proper organisation for the force. The uses to which it could be put were of necessity therefore very limited. They served warrants, guarded courthouses during sittings and occasionally accompanied bailiffs’ parties on seizures or evictions where no trouble was anticipated. Where anything more strenuous or dangerous was involved, the military would be called in and the Barnies sent home. The system worked quite well on the whole as long as the military was available to back up the Baronial Police where necessary. In the years preceding the Act of Union the peasantry had very limited access to firearms or other weapons of war and major disturbances were rare. The peasants only became a police problem wherever large-scale evictions took place, and then they tended to stay around their native districts, sleeping in ditches and living off whatever they could beg or steal. At that stage they became a nuisance and had to be moved on. And if the Barnies were not up to the task, a detachment of Hussars could be readily made available.

But when Robert Peel arrived to take office at Dublin Castle in the autumn of 1812, that simple but adequate system had broken down. From all over the country, magistrates reported grave disorders. Much of that disorder, Peel was ultimately to conclude, was their own fault, but for the present all he could have seen from the urgent notifications of the magistracy was that crime and outrage were on the increase and that the military, whom the magistrates had traditionally called upon to restore order, were simply not there anymore. Huge areas of the South, South-west and Midlands were under the control of outlaw gangs who would descend at night to murder and maim their opponents, burn their homes and drive off their livestock. Moreover, the secret societies had extended their ramifications everywhere, even into the remaining military detachments in the countryside, paralysing the system of informers which in the past had served as an early warning system to the landlords and the magistrates.

But, as Peel was swiftly to realise, the problem was not simply one of a dwindling military garrison and a rise in the crime rate. The Irish magistracy itself was a corrupt institution, operating on an elaborate system of patronage and with little enthusiasm among the magistrates themselves for the preservation of the king’s peace. Reports on the magistracy showed many of its number to be deceitful, violent and seditious and it was not uncommon for magistrates themselves to be convicted for customs and excise offences. In fairness, their inactivity may not have been due entirely to incompetence and indifference. In a community where secret societies, oath-bound bands and violent outrage were increasing daily, the magistrate who would dare to move against lawbreakers would have to be very sure of his own safety and there was not much to be hoped for in the way of protection from either the Barnies or the few remaining military detachments.

Since there was little prospect of bringing the military back to normal strength in the foreseeable future, Peel drew up his own plan for a police force specifically designed to meet the unique requirements of the Irish situation. The new police were to be known as the Peace Preservation Force and they were to be recruited from the ranks of the militia or disbanded regular soldiers. They were to be heavily armed, trained and under the direction of a chief officer who would also exercise some of the powers of a stipendiary magistrate. But the force was not to be allocated throughout the countryside on a permanent or general basis and thus, for the time being at any rate, one of the most distinctive characteristics of the Irish constabulary system – its placing of the police among the people on a local level – was put aside. Full control of the police was thus taken out of the hands of the magistrates, with the result that many of them adopted an uncooperative attitude towards the operations of the new force. Furthermore, the Lord Lieutenant, Whitworth, had turned down an original proposal by Peel that the new police should be recruited from the ‘small farmer’ class and this was to put severe limitations on the usefulness of the force as an intelligence agency since the ex-soldiers and militia men were outsiders, unknown and unaccepted in the rural communities. The Peace Preservation Force was to operate as a flexible and mobile instrument which would be drafted into troubled areas once they were proclaimed under the terms of a new and stringent Peace Preservation Act. While operating in such districts they would be directed by their chief officer who would work in cooperation with the local magistrates and the proclaimed area would bear the expense of the force itself.

In September 1814 the Barony of Middlethird in Tipperary received the first detachment of the Peace Preservation Force. The initial results were encouraging. From a condition of utter lawlessness the barony was swiftly brought to a state in which crime and outrage were for some time completely eliminated.

Applications for the use of the ‘Peelers’ (as the new force became known) poured into the Castle and over the next two years virtually the entire country was introduced to the force with varying degrees of success. It was particularly effective in Cork, Tipperary and Limerick, where its arrival was shortly followed by a marked decrease in crime and outrage. Despite this, it had very definite limitations due to its composition and the fact that it was not locally based. As a ‘flying squad’ it was highly successful, but as a police force proper, capable of anticipating and preventing crime, it had only sporadic success.

The creation of a permanent police establishment throughout the country did not come until 1822 when, in spite of the bitter opposition of the Irish members, Westminster passed an Irish Constables Act which provided for a force to be known as the County Constabulary which, though uniform in its nature throughout the whole country, was, for practical purposes, administered at county level by the magistrates and chief constables. The government had not intended to leave the force under local control but the principle of a permanent and general police system had evoked such a storm of protest in parliament that the concession had to be made. The magistrates retained the power of appointment of constables and sub-constables and this left the way open for the continuance of patronage in the force. Nevertheless, the creation of the County Constabulary firmly established the concept of a regular and general police force as a permanent feature of the Irish countryside, and because the day-to-day running of the force was under the control of the local magistrates, there was little if any of the former influential opposition which had hampered the activities of the Peace Preservation Force. With the blessings of the Ascendancy class, the County Constabulary dealt firmly if selectively with the law and order problems of rural Ireland for fifteen years.

In 1835 the Irish police system was reshaped into the form in which it was to endure until the end of the British rule. The reform was enacted by the Whig government and was placed specifically under the direction of the new Under-Secretary, Thomas Drummond. Drummond, who had caused outrage and anger among the Irish landowning classes by his declaration that ‘property has its duties as well as its rights’ had a deep understanding of Irish problems and a genuine sympathy with the lot of the Irish peasant. He immediately saw that the County Constabulary, in spite of its undoubted efficiency, was regarded by the Catholic peasantry as a partisan force – and not without good reason. The officers were exclusively Protestant and the ranks contained a disproportionately large number of Protestants as well. There were many Orange lodges in the force, often flourishing with the connivance of the magistrates, and the growth of the campaign for Catholic Emancipation in the 1820s was accompanied in many parts of the country by an undercurrent of agrarian tension. In 1826 the campaign reached a peak of excitement and turbulence when the ‘forty-shilling freeholders’ defied tradition and their landlords and voted for pro-Emancipation candidates. Intimidation and counter-intimidation were widespread, Catholic groups were organising protest demonstrations and marching openly, and by 1828 the government realised that it had to cope with an alarming situation of potential revolution. The police played an indistinct role throughout this difficult period, but too often their anti-Catholic sympathies became clear. The attainment of a substantial measure of Catholic Emancipation in 1829 eased political tensions but did not diminish the level of violence in rural Ireland, nor did it serve to improve relationships between the peasantry and the police. The Emancipation controversy had scarcely begun to abate when a campaign began abolish the payment of tithes to the established Church.

So bitter did the ‘tithe war’ become that it was necessary in the period 1830–32 to reintroduce the Peace Preservation Force to augment the County Constabulary in a number of areas. Yet clashes became more frequent and more serious. In December 1831 a mob of several thousand peasants attacked a detachment of police who had come to enforce the collection of tithes at Carrickshock in Co. Kilkenny. Seventeen policemen, including the Chief Constable of the county, were killed and dozens more injured.

Drummond soon realised that the basic fault in the constabulary system was the degree of control which the local magistracy still maintained over it in accordance with the act of 1822. Accordingly, during the parliamentary sessions of 1835–36, he pushed a second Constabulary Bill through parliament, vesting control of a unified Irish police force for the area outside of Dublin in an Inspector-General who would be directly responsible to the Lord Lieutenant and the Chief Secretary. The power of appointment of constables and sub constables was taken away from local magistrates, and inspectors were appointed to direct the force at county and district level. Finally, the four provincial police depots of Ballinrobe, Armagh, Ballincollig and Philipstown, which had served the needs of the County Constabulary, were closed down and replaced in 1839 by a central depot at the Phoenix Park, outside Dublin. A depot reserve of about four hundred men was created to augment the normal complement wherever serious disturbances took place. The legislation providing for the continuing existence of the Peace Preservation Force was repealed and the force passed out of existence.

While the police system of rural Ireland underwent this gradual, if stormy evolution, the City of Dublin had developed its own police force in quite a different idiom, identical almost to that of London and the bigger English cities. Prior to 1842, the responsibility for maintaining the king’s peace in the city and its adjoining townships had rested with the Dublin Watch or ‘Tholsel Guard’ as it was colloquially known. The Watch comprised a couple of dozen elderly men who patrolled the streets at night as best they could in pretentious uniforms of blue and gold. Each constable, while tottering on his rounds, was obliged to carry a lamp and a poleaxe which, together with the heavy greatcoats supplied at the expense of the city, ensured that he was sufficiently hampered not to be able to intervene in any disturbance of which he did not have very adequate advance warning. A popular verse which Trinity College undergraduates were in the habit of reciting in the city’s alehouses gives some idea of the opinion which the citizenry held of these worthies:

Through Skinners Row the toast must Go,

And our Cheers reach Christ Church Yard,

Till its vaults profound send back the sound,

To Wake the Tholsel Guard.

The Tholsel Guard was phased out during the years 1808–42 by a rather haphazard series of statutes which brought into being an unarmed civil force, very similar to the London one, called the Dublin Metropolitan Police. By the end of the nineteenth century, the DMP had reached a strength of 1,200 men and had earned for itself a reputation as one of the best police forces in Britain or Ireland, excelling in some respects even more than the celebrated London Metropolitan Police.

Until 1913, when they became the most bitter enemies of the Dublin working class through the violence of the General Strike, the DMP were a force which was generally well adjusted to the needs and problems of the urban population among whom they lived. Their task was in every respect akin to that envisaged by Peel for the London police: ‘the preservation of life and property, the prevention and detection of crime and the prevention of nuisance and abuse in public places’. Quite different was the role of Drummond’s new constabulary, which operated in a society where virtually all serious crime was politically inspired, where their primary purpose among the people was espionage and where the people themselves had, at best, mixed views of the police.

But the Irish Constabulary, as the new unified police was called, occupied over the next three generations a role in the life of rural Ireland which was considerably more significant than that of the DMP in Dublin. With the gradual restoration of a measure of order into the day-to-day life of the countryside in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, the Irish Constabulary and the people coexisted with less violence, and an element of mutual respect and friendship grew up in the relationship. In consequence, however, the police became the object of more virulent criticism and hatred whenever that delicate equilibrium broke down. The friendliest Peeler was found to be an untrustworthy confidant or neighbour when something went wrong.

In 1848 and again in 1867 the Peelers functioned efficiently and loyally against the Fenian risings – earning on the one hand from Queen Victoria the right to be known as the Royal Irish Constabulary, and on the other an undying hatred and rancour among the rural population.

Yet it would be wrong to describe the relationship which existed in these years between the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Irish people as one of constant enmity and mutual antagonism. The relationship functioned on two levels. Individual policemen in the community were usually respected and even popular. They were the pick of the countryside’s youth; athletic, intelligent and – relative to their neighbours – well educated. They were good customers in small village stores, they could help out with official forms and documents which meant nothing to people who could neither read nor write and they made reliable and desirable sons-in-law. But on the other, more basic, level, they knew and the people knew that when a crisis would come the Peelers’ first loyalty would be to the Crown. They were acceptable when things ran smoothly in the district, but when there was a whiff of disaffection in the air they were the Castle’s men and that basic factor underlaid their affability.

Inevitably there was enmity and antagonism but as time went on its appearance became less and less frequent. The Peelers were generally welcome at weddings, parties or dances. If a Peeler was a good fiddler or dancer he was doubly welcome, and while his mingling too freely with the local population might prejudice his chances of future promotion, that was usually decided anyway by his religion and origins and did not therefore affect his everyday life.

There were a number of good reasons for the growing acceptance of the RIC among the people from about 1880 onwards. The fearful poverty of the Famine era became a thing of the past and the Irish peasantry had begun to savour their first experience of a little security with a modicum of comfort. The sectarian bitterness of the earlier decades of the century had largely disappeared and certainly no longer manifested itself in large-scale violence. Some progress had been made towards achieving tenant ownership of the land and there was to be a continuous advancement in this direction. In short, there had been improvements, however slight, in the lot of the Irish peasant and the main causes of outrage and violence had been somewhat alleviated.

Contemporary accounts confirm the improvement in relations at this time and the police themselves tended to attribute the phenomenon to the growing desirability and acceptability of the police as a career for young men of modest origins and some education. Up to the disbandment of the RIC in 1922, some 30,000 Irishmen had made a career out of the police and some had attained promotion to very senior ranks, although these were almost exclusively the preserve of Protestant members. From 1895 onwards about half the commissioned ranks in the force were filled by men who had risen from the ranks, but the RIC cadet scheme, whereby suitable young men – usually the landless or less fortunate sons of the gentry – were given commissions at the rank of District Inspector, persisted to the end. By contrast with the DMP and British police forces, the RIC observed a rigid distinction between officers and men and the police cadet school in the Phoenix Park depot was regarded as a very suitable finishing school for the less promising sons of Eton or Harrow who did not make it to Sandhurst and who were therefore destined for a career in the constabulary. The cadet school itself was conducted much in the tradition of a lesser public school with constant wagers, dares and practical jokes passing between young cadets and officers. It was traditional that a new arrival would be persuaded, bullied and if necessary beaten into buying supplies of wine for his fellows in the mess and a favourite form of entertainment among the would-be guardians of the law was engaging two mess waiters to put on a human cockfight, battling one another with their feet while their hands would be firmly trussed behind their backs.

For the most part, the officers who left the Phoenix Park depot to take up their appointments in country districts had only a rudimentary training in professional police work. The emphasis during training was on the necessity and means of maintaining discipline among their men and the handling of disaffection and violence among the people. District Inspector George Garrow Green, who left behind an illuminating account of life in the RIC described his state of preparedness on leaving the Park for Listowel, Co. Kerry, in terms which would hardly have elicited the approval of his comrades but which paint a fairly typical picture if one is to judge by contemporary evidence: ‘I could draw a map of Chinese Tartary but had a profound contempt for Taylor on Evidence, I could form a hollow square but of the necessary steps to be taken in a murder case my head was about equally empty. With these advantages I started to assume command of a lawless station in the wilds of Kerry and to instruct the fifty Peelers therein in all that pertained to crime and outrage.’

Inspector Garrow Green was not long in discovering, however, that officers of the RIC had to learn their duties very quickly. The complexities of maintaining order in large, widely scattered rural communities had to be mastered swiftly if an officer was to have the full loyalty of his men. The RIC system depended on the imposition of a rigid organisation and discipline from above, and where any link in the chain of command was broken there was always a danger that the rank-and-file constabulary might move even slightly towards a closer identification with the people.

When the underlying tension between police and people came to the surface, however, it did so with an astonishing severity and viciousness as, for instance, in July 1900 when a dispute developed in the Kilkenny-Waterford district over the employment of police pensioners on local authority work. The argument went on for months until finally the Waterford Star, voicing the opinion of probably a substantial body of the people, came out strongly against the idea of jobs for police pensioners and issued the declaration: ‘The policeman who has done his share of the noble work of spying, evicting and batoning in Ireland should be made to seek other fields when he retires.’ And yet this was in an area which had enjoyed relatively cordial relations between police and population and at a time when there was greater peace in Ireland than at any time in the preceding hundred years. Inspector Garrow Green too was under no illusions and knew that behind the good humour and the harmless roguery the ordinary people ‘still looked forward to the near future and when they would have a police force of their own making’. The people, he recorded, had little of the ‘old respect for the green cloth of the Irish garrison’.

Ironically, it was the unarmed and, in the main, non-political Dublin Metropolitan Police which was first to fall under the wrath of the people in the troubled years leading towards the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and the setting up of the Irish Free State. The Report of the Committee of Inquiry (Royal Irish Constabulary and Dublin Metropolitan Police) of 1914 recorded that the RIC were, on the whole, well integrated among the people insofar as could be expected; it observed that ‘the military character of the Force is passing away’ and that the men do not, as a rule, carry arms, except for drill and for ceremonial occasions. By that time the RIC’s unarmed metropolitan sister-force had been reviled and cast aside by the working-class population of Dublin as a result of their brutality in breaking the General Strike of 1913.

In 1913 the DMP was just under 1,200 strong and was still regarded as a model urban police force in international police circles. Relations between police and all classes of society were good and the police bands and mounted sections were in great demand for public functions, processions and celebrations. A celebrated tradition of physical fitness had been built up in the force and its tug-of-war team had several times carried off British and European trophies. In 1844, when the force was just over 1,000 strong, 942 members were recorded as being 5 ft 9 in or over, 153 were 6 ft. or over and 36 were 6 ft 2 in. or over. By tradition the tallest men policed the B District, which comprised stations at College Street, Lad Lane and Clarendon Street and which covered the south side of the city centre between the Liffey and Grand Canal Street, bounded on the west by South Great George’s Street, Aungier Street and Camden Street. In 1876 the average weight of members of the force was 12 stone 11 lb and one celebrated Constable Woulfe was recorded at 20 stone with a height of 6 ft 6½ in.

The DMP was part of Dublin’s very life, an institution in the capital, as much an integral part of the city as Guinness’s Brewery or Nelson’s Pillar.

All that changed in August 1913. Dublin was paralysed by a general lock-out as Jim Larkin, the trade union leader, organised the workers to stand up against the employers and profiteers who kept them and their families in what had become notorious as the worst slums in Europe. For reasons which have never been fully explained, the police charged a huge crowd which Larkin was addressing. In the charge and in subsequent skirmishes through the centre of Dublin which lasted for several days, at least three people, including a young woman, died. The DMP were immediately identified by the Dublin working class as the agents of the employers and a rift developed which has yet to be completely re-bridged.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly the reasons for the ferocity of the Dublin police force’s attacks on the strikers of 1913 – the people who had adored and cheered them in the past. But it cannot have been unconnected with a growing mood of resentment and viciousness within the force at inadequate pay and worsening conditions of service.

Between 1903 and 1913 there had been a marked fall-off in the desirability of the police forces as fields of employment. Pay had not been increased to match the cost of living and the police had lost considerable ground compared with other urban occupational groups.

Resignations from both the DMP and the RIC were increasing. In 1903 there were 85 resignations from the RIC; in 1911 there were 163, and in 1913, 299. In 1901, while pay in the better British police forces varied between £1 9s. 9d. a week and £1 10s. 0d., the pay of the DMP constable was £1 10s. 0d. RIC constables received only £1 7s. od. In 1914, when British police rates jumped to £1 18s. 0d., for example, in the case of the Sheffield police, the DMP man was still receiving only £1 10s. 0d., while the RIC man had gained a shilling increase, giving him £1 8s. 0d. a week. By contrast, Dublin bricklayers in 1914 earned an average wage of £19s. 7d. a week, stonecutters earned £1 15s. 5d. a week, and plumbers earned £2 1s. 7½d. Labourers’ earnings varied between £1 0s. 10d. and £1 1s. 10½d. a week.