Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

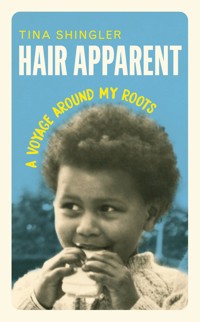

Growing up in the '60s as a Black face in a white space, Tina Shingler always knew that her well-being depended on her ability to assimilate. As a Black Barnardo's child, Tina was 'boarded out' to a white foster family in rural Yorkshire. Overwhelmed by the complex texture of Black hair, her foster mother resorted to chopping back Tina's curls as close to her scalp as possible. Being unceremoniously shorn like a sheep felt like a punishment for having such troublesome hair. Today, however, many Black girls are growing up confident in the knowledge that their naturally kinky hair in all its amazing transmutations is a powerful expression not only of their identity but also of their individual style. And despite getting off to a bad start with it, Tina has 'grown into' her hair and now appreciates and enjoys its incredible versatility. It has helped her understand herself better, forge her own identity and create a sense of her own worth better than any self-improvement manual. An inspirational 'hairmoir', Hair Apparent embraces the powerful legacy of Afro hair across several countries and seven decades of social, political and cultural change. Right now, Afro hair is living its best life, and Tina's manifesto of survival, resilience and identity helps us praise it like we should.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

iii

To Chloe and Felix Mills,

Mayyoualwaysblossomwhereyouareplantediv

v

‘You can never cross the ocean unless you have the courage to lose sight of the shore’

Christopher Columbusvi

Contents

Preface

I grew up a Black Barnardo’s child in the ’50s and ’60s and at three years old, official records show that I was ‘boarded out’ into the foster care of a white, working-class family in a rural community in Yorkshire. I was one of the lucky ones, bypassing the dead hand of institutional care for the comfort of a regular family. My foster family was not regular by any stretch, but they were kind and caring and that was more than enough; more than an unwanted Black kid had any right to expect, some uncharitable voices were quick to say. With Barnardo’s as my constant overseer, I was expected to reflect their Christian values and so I was hastily baptised by my new foster family and began to attend Sunday school regularly. From my earliest days as a hi-vis outlier, I knew that I had a job to do: I must do everything possible to fit in. While it was clear that I was never going to blend naturally into xmy surroundings, I must at least try to ‘normalise’ my Black self within the small-town parameters. My mission was simple: to be as good as gold and to be no trouble to anyone. The alternative was all too real. The fear of being sent back into the anonymity of institutional care hovered over my childhood like the sword of Damocles.

Whenever I came home from school and saw the familiar car of the Barnardo’s visitor parked outside the gate, I’d get an anxious twinge. The little Morris Minor belonged to Miss F, who I knew was here to file a full report on me back to the Barnardo’s Mothership. This middle-aged lady was kindly enough, but I knew she was here to probe my foster parents and then me about my merits, misdemeanours and character flaws. Miss F’s regular visits were a constant reminder of my privileged status in a proper family; a status that must be earned and that could be revoked at any time. She was the ultimate deterrent to behaving badly, and knowing my status was conditional felt like being on indefinite probation.

While emotionally, I could always go into hiding, physically, there was nowhere to run. I was out there in plain sight: the Black kid with the crazy mop of hair. More than my hi-vis skin tone, it was the strange texture of my hair that was a talking point, and more often than I liked, it was a touching point too. My hair was quite literally up for grabs, as adults and children alike felt free to tug and xipoke at it with curiosity. From their scornful looks and comments, I began to understand that my hair was an unruly beast and trying to tame it was as much a public service as a personal pressure.

So, growing up in the ’60s as a Black face in a white space, I always knew that my well-being was conditional, even precarious. Popular British TV comedies of the time reminded me of this with their unapologetic derision of ‘wogs’, ‘coons’ and ‘fuzzy-wuzzies’. Meanwhile, primetime Saturday night viewing was The Black and White Minstrel Show, where white men got up in blackface and woolly little wigs, sang and danced with leggy white girls in a wonderland of showbiz glamour and sparkle. What to make of it? These were confusing signals for a lone Black girl swimming in white waters. I learned that faking being Black was high entertainment and jolly good fun for all the family. But as the Conservative MP Enoch Powell reminded us in his famous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in 1968, nobody likes the real thing. The vocal anti-immigration lobby made no fine distinctions between a newly arrived Black population and those born in Britain who knew no other country, no other reality. We were all the same colour, weren’t we? We weren’t welcome and we should all go back to where we came from. And in my little corner of the world where White Was Always Right, the message I received loud and clear was that while I might be allowed xiionto the boat, I had better not start making any damn waves by rocking it.

Many young Black people are now growing up confident in the power of their naturally kinky hair and all its amazing transmutations. As well as inspiring endless artistic and creative interpretations, its shapeshifting properties allow them to continually reinvent themselves. By resisting the use of harsh chemicals to alter its texture, their hair projects a sense of pride and a belief in their natural beauty. They get it. They always did. They understand its language and they have learned to express their personalities through the myriad of inventive styles its peculiar strength and density inspires. For them, I hope that these pages will be a recognition and a celebration of what they already know: that they have springing out of their scalps something so electrifying, so complex and so terrifically versatile and beautiful that it’s like having an extra gear not just to their look but to their whole personality.

But alas, it wasn’t always so. History has not always allowed earlier generations of Black women to take a rightful pride and joy in their natural Afro hair, and their ‘hairstories’ have been ambivalent ones. The intricate texture of their hair has been weighed down with social and political history in every kinky curl. For years, the pressure to conform to a ‘white norm’ has skewed their vision of xiiitheir natural beauty and led them to undervalue one of our most outstanding physical assets.

It’s a pressure that has been ingrained since childhood and it’s followed us into the classroom, the workplace and our most intimate relationships in adulthood. In our relentless efforts to ‘unkink’ our hair, we have overheated it with powerful dryers, hot combs and straightening tongs, literally scorching and sizzling the life out of it. We have chemically ‘relaxed’ it again and again, exposing ourselves to toxins that we now know to have damaging effects not only to our hair but potentially to our long-term health as a whole. The war to convert our hair to what we’ve been led to believe is the True Way, the White Way, has been a holy crusade fought with righteous determination and aided with evermore ingenious weaponry created by the big pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies. In the process, we’ve caused untold physical damage to ourselves while chipping away at our self-esteem.

This relentless sense of feeling ‘less than’ has been exacerbated for those of us who, for whatever reason, were forced to live our Black experience in isolation from Black communities. Our hairstories have often taken us on a long and lonely road trip towards self-acceptance and we have struggled to fully appreciate the amazing properties of the natural texture of our hair. Overwhelmed by the xivcomplexity of its texture, we were at a loss as to how to care for it practically and emotionally.

We displaced Black girls inherited none of the nifty braiding skills and intensive haircare rituals that Black women pass on as a matter of course to the younger generation – rituals embedded in earliest memories and which connect us to tradition, family and a sense of belonging. When we looked to see who was behind us, who we could learn from, there was no one there. We had no role models, no one to emulate or to guide us. We lacked the cultural confidence to view our hair with anything but the alarm and dismay we saw in the white eyes of our carers and those around us. Our only inheritance was frustration and an unspoken sense of shame. It’s as if we were missing a vital key to our identity right from the start.

In absorbing this white angst around our hair, we’ve felt little love for it and, by default, little love for ourselves. We’ve grown up hearing the words ‘frizzy’, ‘bushy’, ‘wiry’, ‘unmanageable’ and ‘impenetrable’ and we’ve accepted them because there’s been no one around to tell us otherwise. With no one to teach us the basics of Black haircare or the loving patience needed to manage it properly, our relationship with our springy, often intractable curls has been a combative one. In the process, there’s been a sense of something lost, personally and culturally.

I like to think that, despite getting off to a bad start xvwith it, I’ve ‘grown into’ my hair now and I’m able to appreciate and enjoy its incredible versatility. Just knowing that this complex network of twisted coils springing from my scalp links my DNA to generations of Black women near and far, and to their extraordinary tales of survival, strength and creative genius, is a terrific inspiration. It has helped me understand myself better, forge my own identity and create a sense of my own worth better than any self-improvement manual.

Over the years, in my writing, I’ve made random references to the challenging texture of my hair and people’s responses to it; the good, the bad and the downright ugly. It was only when I began patching some of these extracts together that I realised I’d got not only some compelling hair adventures but a personal ‘hairmoir’ spanning several countries and more than seven decades of social, political and cultural change. This seemed like something worth developing and maybe even sharing. Before I knew it, I was writing a personal manifesto of survival, resilience and identity, as I unravelled my own lifetime’s relationship with my hair. Testing the waters, I created a presentation around it with photos and musical extracts and took it into schools, businesses, libraries and local arts festivals. Vibrant feedback from audiences both Black and white sparked conversations on everything from racial justice, politics and social history to feminism, self-esteem and xvithe thrilling power of creativity. It was these waves of positive energy that powered the writing of this book.

You can spend your whole life trying not to rock that blasted boat. You hold steady as you navigate the dangerous shallows and rocky outcrops, and all the time, without really knowing it, you are quietly going under. You are drowning a little inside. Then, one day, you decide maybe you’ll build your own boat. You’ll build it to your own specifications and you’ll set your own course. Like most adventures, it’s scary at first, but you’re free and sailing solo. You’re ready to revisit some familiar places and maybe discover some new ones along the way. You’ve finally got a clear view all the way to the horizon. xvii

xvii

‘This too I have learned from the river: everything returns’

Siddhartha, Hermann Hessexviii

Chapter One

After the Taj

Long before the Beatles were getting their minds blown by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, I had my own ideas about India. From the moment I discovered the National Geographic collection in the school library, I was drawn to its powerful mystique. India was where the mighty Himalayas gouged clouds with a remote, cold beauty. It was a country crammed with Mogul forts and palaces, Hindu temples, mosques and teeming, ramshackle old cities tumbling down to the banks of the sacred Ganges. But it was in 1968, when we saw those first pictures of the ‘Fab Four’ bedecked with flowery garlands sitting at the feet of their guru, that India entered world consciousness as a place of deep mysticism and spiritual awakening. Those pictures captured the ‘wild child’ spirit of the late ’60s with its hippy-trippy slogans of ‘Turn on, tune in and drop out’ and ‘Make Love Not War’. All at 2once India was the ‘hip’ place to be and Transcendental Meditation or ‘TM’ was the ‘groovy’ thing to do. Sitting cross-legged like preschoolers with their benign-looking yogi, the Beatles were smiling, portraying an air of hopeful innocence. Gone were the famous smirks and cheeky grins. They looked becalmed, receptive. In India, they were ready to relearn themselves. And they made it look so easy, we were more than willing to believe it. Peace be the journey.

But even if I’d had the makings of a hippy, at fourteen, I was still too young to pack my bags and head east in search of enlightenment. I had homework and hockey practice to worry about. So, like everyone else, I settled for wearing a lot of cheesecloth with strings of ‘love beads’ and reading Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, the spiritual handbook of the ’60s. My road to self-discovery would have to be put on hold for a few more years, or at least until I’d finished school. But just wait, I promised my teenage self; one day I’ll have my own spiritual journey, see if I don’t.

Like Siddhartha’s river of many voices, the years went slipping by, sometimes in a noisy babble and sometimes in a murmur. I grew up, went to university, lived and worked in both Italy and the US for many years. I married and had a dazzling daughter. Life began to squeeze, with the demands of work, family and relationships gobbling up all my energy. Opting out to ‘find myself ’ in India, or 3anywhere else on the planet, became the stuff of idle, youthful, even selfish, fantasy.

It would be more than thirty years after the Beatles’ inspirational journey east that the stars aligned for me with India.

By then, I had been working as a government press officer in Yorkshire for more than ten years. Writing press notices and media plans, rallying journalists, meeting and briefing government ministers, I was doing the bidding of Whitehall departments ‘up north’. Now I was a fiercely independent, middle-aged single parent, which meant my daughter and I were entirely reliant on my salary alone. I was lucky. It wasn’t such a bad salary, but it had to go a long way and it was often a struggle. I wasn’t unhappy. I had a decent job, great friends and a terrific kid, but there was a nagging sense of lack within me; a feeling of being hopelessly ‘stuck’ in my own life. Like the computer screen I stared into for several hours every day, I longed to be refreshed, maybe entirely rebooted.

So when my church congregation announced a tour of the sacred sites of northern India, it was as if a long-lost prayer were being answered; a reminder to keep faith with past dreams and aspirations. Just reading the proposed itinerary gave me a rush of excitement. I could already feel something inside me beginning to shift. There were visits to a Buddhist monastery, Hindu temples, mosques, 4the Taj Mahal and the Sikh Golden Temple at Amritsar. Just the thought of India felt like the first cool drops of rain on my parched soul. India would unlock me. It would free whatever it was that felt trapped inside me – hope, ambition, inspiration, passion? So far it had no name, no voice and no shape.

It had been a long time coming, but this, I told myself, was my moment. Surely I’d earned this.

India would transform me; I was certain of it. I would come back different. I would be chilled out and destressed. I might even take up yoga and meditation; maybe get a taste for brown rice and mung beans. I remembered the Beatles with the Maharishi and their cosmic smiles. All these years later, of course, the world was less naive; we now know those pictures had been carefully curated for the international press and that behind the Maharishi’s benevolent smile was a man on the make. But whatever had happened to the Beatles in India, it had changed the direction of their music and their lives. Now it was my turn.

Siddhartha’s river was calling me and I was ready to listen.

India wallops your senses. Nothing prepares you for the staggering assault of its noise, its smells and its scalding colours; they swamp you, swallowing you up like a tidal wave. Take a rickshaw ride through the rollicking chaos of 5downtown New Delhi and you feel as if, before coming to India, you’ve been sleepwalking through life. You’ve been sleepwalking in a monochrome world with the volume turned down.

The heat may hang heavy as a damp blanket, but underneath it I’m feeling as stripped and raw as a freshly peeled prawn. My pores are wide open, my senses tingling. I mean to suck up every moment of this experience. I’m ready to let India happen to me.

Like the rest of the group, I was overwhelmed by the strange newness of everything I was seeing and feeling. A big part of this was getting used to the clinging entourage of beggars that all tourists acquire in India. We had only to step off the coach and we were besieged and then aggressively pursued. Our Indian guides cut a swathe through them, swatting them off like flies with what seemed to us a callous indifference. But, running the gauntlet of those imploring faces, pitiful pleas and outstretched hands, it was hard to pretend that these wretched souls were no more than a minor inconvenience to be navigated.

Reading and hearing about the poverty in India is one thing, but seeing the everyday reality of desperate and grinding deprivation was an almighty shock. It was a sickening moral dilemma. Give to one and be mobbed by all of them; or follow the lead of our guides and slice through them like a Swiss Army blade, looking neither 6to left nor right. It was a lot to take in; compassion and guilt battling with our natural alarm and fear of being set upon.

So it was a while before I noticed that alongside the gangs of beggars who followed us all, I was attracting a separate little posse of hangers-on, a splinter group who only had eyes for me.

‘I see you’ve got another fan club,’ said one of my fellow travellers as we all stood outside the magnificent Red Fort in Delhi while the guide negotiated our entrance.

He nodded towards a rag-tag bunch of street kids who had been trailing us from the coach park. They now stood off at distance, jabbing fingers in my direction and hooting with laughter. I shrugged and forced an amiable smile that belied how unnerving I found their attentions.

The truth is this kept happening. These kids would spring up everywhere, running alongside me in twos and threes until their excited jabber and laughter recruited others. God alone knew what they were saying, but it was clear that I’d been singled out as a figure of fun. Now, I’ve never minded people having a laugh at my expense. In fact, over the years I’ve become a master in the art of self-deprecation, especially if the payoff was a laugh all round. But these kids were laughing right in my face. These kids were jeering at me. Apparently, I was an absolute hoot. It was hard to make light of the relentless harassment 7that made me feel so awkward and freakish. To save face, I pretended to share the good-natured bemusement of the rest of my group. Kids, eh? What can you do? But in reality, I was embarrassed and confused. What did they want? Why couldn’t they leave me alone? I couldn’t seem to shake them off. My role as a reluctant Pied Piper was becoming a damn nuisance.

At first, I was mystified. I just didn’t get it. True, as the only Black person I definitely stood out in our small British party. But so what? You only had to look around to see that a lot of Indian people – including most of these tormenting kids – were a whole lot blacker than I was. So what the hell was the joke? Then it hit me. Of course, it wasn’t me they were guffawing at. It was my hair. These Indian kids had never seen anything like it. It was my natural kinky hair that had them in stitches. What the hell was that springy stuff standing out on top of my head? Whatever it was, it was hilarious. I was a walking comedy act.

I was mortified and I was angry. Remember, they’re just kids, I told myself in an effort to claw back some perspective. They’re doing what kids do. They’re poking fun at something unusual. And here in India, it just happens to be you and your head of hair. Get a grip and keep your cool.

I thought back to my own daughter in her pre-teen years. How she would pester and harangue me with 8repetitive demands about sleepovers, new shoes or upping her pocket money.

‘For heaven’s sake, will you stop annoying me!’ I would plead.

‘I’m a kid. That’s my job,’ she would answer, without missing a beat.

These Indian kids were only doing their job. Doing what came naturally. They were annoying all right, but to them I had a comical head of hair that was pure entertainment. I was the funny woman with stand-up hair. Still, it felt like a kind of persecution, although they could have no idea of how humiliating I found their attentions, how embarrassed it made me feel in front of the rest of the group I was travelling with. But I was all grown up and I wasn’t about to let a bunch of feral kids get to me, was I? India was a once-in-a-lifetime experience for me. I was on a spiritual journey here, a quest for deeper meaning.

All you have to do is ignore them, I told myself as I tried to quiet their mocking jibes with some of the meditation techniques I’d been reading up on.

Just breathe. Be the calm you are seeking. Choose stillness in the midst of movement and chaos.

Then we arrived at the Taj Mahal.

Like Mickey Mouse is to America, the Taj Mahal is everyone’s quick cultural reference to India. But no matter how many times you’ve seen it in books, travelogues 9and on TV, nothing comes close to the moment you step through the great arched gateway and get your first breathless glimpse of its dream-like sublimity. There are no superlatives. At first sight, I remember being afraid to blink in case it simply evaporated like the shimmering mirage it seemed to be.

It didn’t evaporate, of course, but I very soon wished that I could.

On either side of the long reflecting pool leading up to the Taj, all I could see were droves of kids being herded about by their teachers. In their crisp school uniforms and in orderly crocodile formation, these children were a world away from the ragamuffins on the streets of New Delhi. They were middle-class kids on a school trip to their country’s most iconic monument and they were under strict supervision. Just look how the teachers were keeping them in line.

Translucent and glowing like a magnificent opal in the morning sun, the Taj lay before me; but even as I tried to draw on its cool and timeless serenity, part of me was fighting the urge to head back to the sanctuary of the coach.

For once in India, I was glad of the crowds. There were people surging everywhere in and around the grounds of the Taj. Like a tiger in the long grass, I hoped I’d be able to conceal myself more easily. 10

But once the first sharp-eyed kid spotted me, it was open season. After being drilled about the history of the great Mogul dynasty, the architectural symmetry and splendour of the Taj and the tragic love story behind its creation, here at last was the light entertainment. Bring on the clowns. Me and my frizzy mop were the comic relief. Now, as each school group alerted the next, all eyes shot in my direction and a wave of shrieks and giggles rippled down the line like an electric charge. Teachers, barely concealing their own mirth when they saw me, were struggling to keep order in the ranks.

So much for cool serenity; I felt grotesque, ridiculous. I was the bearded lady, the freakshow.

I had no control over the kids’ reactions; all I could do was try to manage my own. Rising above it and pretending not to be bothered seemed the only dignified option. I tried to take refuge in irony. Imagine, these kids had come from all over India to marvel at one of the most breathtaking monuments in the world; this was their stupendous heritage. Yet here they were goggling and pointing fingers at the woman with the weird hair. Hard as it was to believe, my wiry curls were threatening to upstage the Taj Mahal.

It was meant to be the high point of the whole trip, but for me the Taj Mahal marked a ‘before’ and ‘after’ in India. After the Taj, I was desperate to keep my hair in 11hiding. The first chance I got, I went out and bought a lot of cheap silk scarves and pashminas. It was time to get inventive. I devised a colourful range of head wraps and turbans, twisting and tying them into elaborate styles, anything to hide my laughable head of hair. I’d often enjoyed wearing head wraps as a fashion choice, but in India it felt like an urgent cover-up. It was as if I were hiding a shameful secret, a deformity that must be kept out of sight at all costs. After the Taj, I covered my head all the time in India. My hair was turning out to be too damn sensational. It was provoking too much unwanted attention and it was seriously hampering the path on my spiritual journey.12

Chapter Two

Growing Up with Golly

With my hair under wraps, I drew no more attention in India than any other tourist. Visiting the temples, mosques and holy shrines, I merged back into the group again and I no longer felt like I was heading up a circus parade with a riotous band of followers at my heels. Now, instead of just moving about in India, I could begin to let India move in me. What didn’t change, however, were the thrusting gangs of beggars who sprang up wherever we went. But after our first encounters with them, when we’d recoiled from their determined assaults, it was surprising how quickly we got used to them. They were part of the Indian landscape, inevitable and unavoidable. When we could, we gave, but most of the time it was impossible without inciting a mob scene. Instead, setting our 14eyes on the middle distance, we learned to move our way through them.

Perched in the foothills of the Himalayas, the Buddhist monastery at Dharamshala has ravishing views into deep-wooded valleys that swoop up to colossal snow-capped peaks. The red-robed monks glide about with ineffable calm under strings of bright prayer flags that flutter and snap in the mountain breeze. The waft of incense is everywhere. In the cool innards of the temple, the monks’ hypnotic chanting evokes an overwhelming sense of peace and harmony that seems to still the soul. Surely, if ever there was a time and place to get right with your inner rhythms, this was it. Yet for all the transcendent atmosphere of Dharamshala, I felt more like a journalist, observing and taking notes, than a pilgrim on a spiritual quest. Try as I might, I couldn’t seem to plug into the prayerful aura around me. It was as if my spiritual wick had been dampened. It refused to be lit.

The pestering kids were gone now, but I could still hear their gleeful mockery. I had let them get under my skin, and now their shrieks of taunting laughter were permanently in my head like an annoying earworm. They had kicked open a door into my childhood and the past now roared into the present with a storm of memories.

I was the little ‘coloured’ girl again in an all-white rural community in Yorkshire; the little misfit ‘half-caste’ with 15the strange mop of frizzy hair who always kept my head down because I never knew when I might come under fire. It could happen anywhere, in the schoolyard, on the street, in the playground by the swings. Often, I could see it coming and I would brace myself for impact, but it could just as easily be a stealth attack catching me off guard, sudden and ruthless. All I knew was that once I left the shelter of my foster home, there were no safety zones. It could be this kid walking towards me who would harass me, or the abuse could come from that kid at the top of the street. Then there were those lads from the local housing estate who never missed an opportunity for a potshot. I was such an obvious, irresistible target. I was asking for it. And it was always the same sneering words spat out like bullets: ‘NigNog’, ‘Blackie’, ‘Wog’, ‘Coon’ and sometimes, like the coup de grâce, the full stinging force of the ‘N-word’.

In general, there wasn’t much call for this kind of language in small-town North Yorkshire, so these words, that I only ever heard around myself and my foster sister, seemed to hold an added relish for our tormentors.

But just as often it was the more benign ‘Fuzzy-wuzzy’, ‘Mophead’ or, in the broadest Yorkshire dialect, ‘Gerraway, you don’t call that stuff ’air, do you?’

All this time and I’d thought the wounds had scarred over; but from Delhi to Dharamshala, scenes I thought 16long forgotten were surfacing again. That lone little Black girl was still with me. And so was her hair; and even after all these years, it still had the power to diminish me.

Growing up in a white foster home in an all-white community, I found that my hair’s unusual texture was met with curiosity and often with outright derision: ‘Here, let’s have a feel of it’ and ‘How on earth do you comb that stuff?’ or ‘What kind of shampoo do you use? Is it the stuff they use to clean carpets or what?’

My hair didn’t behave like regular hair. It didn’t grow down; it grew out. It wasn’t loose, so it didn’t blow about in the breeze or fall into my eyes. In fact, it didn’t move at all. It was static. I got so used to people making fun of it that I too could only think of it in terms of a joke; a joke that I couldn’t bring myself to laugh about.

There’s a photograph of me at four years old posing with my Black foster sister. Together we were pretty much the entire Black population of the small market town where we grew up. And yes, shocking as it might seem today, we are dressed up as golliwogs. It was the annual fancy dress parade and this was our white foster mother’s idea of ‘working with what you’ve got’. And what we had got was our dark skin and crazy fuzzy hair. What we had got was that we were golly lookalikes.

But don’t think for a moment we were random golliwogs. 17We were the Robertson’s Golden and Silver Shred gollies straight off the jam jars. In fact, a closer look at the photo reveals we have oranges and lemons in our little baskets and we are proudly sporting our golly badges. For those who won’t remember, the badges were an early version of the loyalty card; the idea being that you got a ‘free’ enamel badge when you had collected so many golly labels from the back of enough marmalade jars. The infectious TV jingle urged us to keep our eyes peeled for the golly. And we did. We all did. In his familiar royal blue tailcoat and red bow tie, the Robertson’s golly mascot was a phenomenal advertising success that was first dreamed up in 1928. More than 20 million golly badges were distributed across Britain before he was finally ‘retired’ in 2001. I know! 2001, you say. That’s how long it took advertisers to recognise that the racial undertones of the mascot were no longer appropriate in Britain’s fast-changing demographic; that maybe, just maybe, a pop-eyed, grinning and capering Black minstrel selling their jam products wasn’t considered that cute any more. You think?

Be that as it may, back in the 1960s Robertson’s golly reigned supreme. The jolly little fellow was a household favourite who was instantly recognisable everywhere. So I can’t help feeling that Mary, our foster mother, knew she was onto a winner as she knocked up our little golly suits on her old Singer sewing machine. We were such a 18safe bet. Not one but two little Black girls got up as the famous jam-jar gollies. We were naturals (no boot polish required). We were sure to turn heads and very likely to win prizes.

Some of the entrants in the fancy dress parade that year felt robbed as there was no third prize. The two Robertson’s gollies swept the competition off the board and came in joint first. I seem to remember that Little Bo-Peep, with bonnet and shepherd’s staff, wept inconsolably, while the Lone Ranger was too busy ‘shooting’ imaginary ‘Injuns’ to care. As for the winners, well, there they stand in front of the sweet pea canes in the garden, and I just thank God we were both still too young to get the joke.

There was a time when I used to have a lot of trouble looking at that photo. Apart from the implicit irony of the picture, then and now, I recognise that little girl with her costume slightly askew. I know her. There’s no getting away from her. She’s wary, uncertain and camera-shy. She’s tired of always being looked at, always noticed and remarked upon. And she’s already taking refuge in books to escape from prying eyes and questions. Reading, I was discovering, was a good get-out for not engaging with people. With my head, quite literally, in a book, I was more likely to be left alone or overlooked. Unlike my foster sister, who was a year older and more easy-going, smiling at the camera didn’t and still doesn’t come naturally to me. 19

Like most women of her generation, Mary was an accomplished seamstress and it’s easy to see that she took a lot of trouble making our costumes. But what leaves a real impression in the photo is the state of our hair. Sticking up in matted clumps, it looks not so much unkempt as utterly unloved. I don’t know about my foster sister, but even at this early age, I’m pretty sure that I was already suffering from acute hair-anxiety. All the photos from around this time tell the same unhappy hair story.

But if our hair was neglected, it wasn’t for want of trying on Mary’s part. She did her best, but what did a white working-class housewife know about managing the complex texture of hair like ours? How could she have any idea of how to manage such alien stuff? But as a practical, down-to-earth Yorkshire woman, Mary nevertheless rolled up her sleeves with every intention of ‘fettling’ it.

Fettle: it’s a good, solid word, isn’t it? The Oxford English Dictionary