Harvest E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

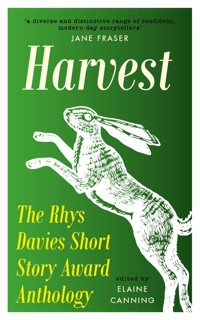

'Atmospheric, suspenseful and full of symbolism, it's encouraging to see the wealth of Wales-based talent showcased in the short story form; Harvest offers excitement at what the future holds.' – Rhianon Holley, Buzz Magazine Inquisitive children and solitary beings; conflicted couples and a sprinkling of spirits and monsters: these are just some of the characters which inhabit the twelve stories in this collection of new contemporary fiction by the winners of the 2023 Rhys Davies Short Story Competition. A young girl discovers a body in the woods near her home; a man lords over his cockle-beds; and a holidaying couple set off on a nocturnal mission. A group of children enlist the help of a witch to assist a dying relative, while a local talent show casts a spotlight on hopes and dreams. From an All-American Diner deep in the Rhondda to rural Welsh landscapes, working-class communities and cultural and linguisitic journeys beyond Wales, these stories combine traditional storytelling, realism and magical realism as protagonists face their demons head on. They are stories about longing and belonging, departure and desire, sparking with originality. A collection of new contemporary short stories by Welsh writers, representing the winners of the 2023 Rhys Davies Short Story Competition. The Rhys Davies Short Story Competition recognises the very best unpublished short stories in English in any style by writers aged 18 or over who were born in Wales, have lived in Wales for two years or more, or are currently living in Wales. Originally established in 1991, Parthian is delighted to publish the 2023 winning stories on behalf of the Rhys Davies Trust and in association with Swansea University's Cultural Institute. Previous winners of the prize have included Leonora Brito, Lewis Davies, Tristan Hughes, Naomi Paulus, Laura Morris and Kate Hamer. Authors in this anthology: Ruairi Bolton, Ruby Burgin, Bethan L. Charles, JL George, Joshua Jones, Emma Moyle, Rachel Powell, Matthew G. Rees, Silvia Rose, Satterday Shaw, Emily Vanderploeg and Dan Williams.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 255

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iiiiiiiv

HARVEST

The Rhys Davies Short Story Award Anthology

Edited by Elaine Canning Selected and Introduced by Jane Fraser

Contents

Introduction

Jane Fraser

I hold my hand up that I came to the work of Rhys Davies later in life than I would have wished. However, it was not too late thanks to award-winning Welsh author, friend and former short story mentor, Jon Gower. It was Jon who signposted me to the Rhys Davies Short Story Conference held at Swansea University in 2013: an event dedicated to one of Wales’s most prolific prose writers. Here I discovered that during his career, Blaenclydach-born Rhys Davies (1901 – 1978) wrote more than one hundred short stories, in addition to twenty novels, three novellas, two topographical books about Wales, two plays and an autobiography.

Looking back, this was a pivotal few days at the early stages of my personal writing journey, a few days where I made further discoveries about the creative possibilities of the short story genre, and reinforced my belief that the short story was a beautifully compressed and controlled art form, its writing no way an apprenticeship to writing a novel.

Following the conference, I immersed myself in Davies’s short stories, drawn in by the feelings of loss, loneliness, longing and the search for identity, inclusion and belonging, exhibited in his characters, especially women. He wrote of life’s ‘outsiders’ in Wales from his perspective as a gay man, living in exile in London at a time when homosexuality was a criminalised offence. With the lost and the lonely came humour 2and a keen ear for comedic dialogue. It was a powerful combination: what I came to term ‘the Rhys Davies effect’.

To be asked to guest-judge the 2023 Rhys Davies National Short Story Competition (the tenth in its history) is therefore a privilege and a pleasure. It is both subjective and objective: subjective in that I can empathise with the entrants’ desires to correspond with a reader on the page, perhaps for the first time in their writing careers, and objective at the same time, having to identify those anonymous writers who demonstrate excellence in the territory of the short story: theme; characterisation; point of view; tone of voice; control of the narrative; effective handling of time – where to begin and where to end; the power of the unsaid; and the ‘feeling’ that the short story leaves behind after the last sentence is read. And that indefinable, magical relationship between writer and reader. I wanted to read stories where I could feel the writer taking an in-breath at the beginning, sense the energy being maintained throughout, and where the out-breath at the end gave me a feeling of satisfaction, even though that ending might not be tied up. All this in a maximum of five thousand words.

What I was looking for can perhaps be better expressed by the wonderful short story writer, George Saunders, who says that short stories are ‘the deep, encoded crystallisations of all human knowledge. They are rarefied dense meaning machines shedding light on the most pressing of life’s dilemmas.’ I wanted stories that would enable me to understand what it feels like to be human. No artifice. No sentimentality. Rather, authentic and emotional truth. And it was this truth I found prevalent among the thematic concerns in the twelve stories I selected.

The themes of loss and longing figure highly in many of the stories. ‘Nos Da, Popstar’ by Joshua Jones, sees a girl dreaming 3of winning a talent show, but the restrained subtext makes it clear and without drama, that this is not what she is really wanting. The story creates an authentic sense of contemporary pop culture and a real sense of a working-class area of Llanelli – heightened by the writer’s keen eye for signposts in the landscape and a keen ear for authentic dialogue and the vernacular. So too, in Rachel Powell’s ‘Bricks and Sticks’ we see the female protagonist longing for what has passed, and anticipating grief that is yet to come in a house that holds love and family memories. The writer takes the domestic and the apparently ordinary and conjures a tale that is universal, full of feeling and most definitely, extraordinary.

Regret, resentment and the life not lived are the themes of Dan Williams’s powerful story, ‘The Nick of Time’, set in Trwm Ddu (Heavy Black) Powys, where the external landscape and the internal thoughts of one of the central characters seem intertwined. The narrative simmers with rising tension and claustrophobia as it comes to the boil. Set in Wales (or ‘your land’ as one of the story’s characters refers to it) ‘Welcome to Momentum 2023’ by Emily Vanderploeg is an ironic exploration of ‘outsider’ perspectives on Wales. Tone of voice is maintained throughout this wry story of the loss of cultural traditions and language and Wales selling its soul as a theme park. ‘Save the Maiden’ by Bethan L. Charles revisits a tale from Welsh folklore in a timeless story of apocalyptic floods, maidens and monsters, told with a feminist twist. The rhythm of the prose is wonderful, and the language beautifully wrought.

‘We Shall All Be Changed’ by Satterday Shaw and ‘The Pier’ by Emma Moyle both have interesting perspectives. The young, science-loving female protagonist in the former ‘doesn’t know how she feels’ and employs her peculiar logic when she 4encounters the dead body of a woman in Coed Felin. The close third person narration employs a register that translates the character aptly. In the latter, an omniscient, multi-perspective journalistic/reportage story, darkness and menace play out in a one-day time frame on the pier and amusement arcade in Wales, with security cameras used effectively as characters offering an additional point of view to the events that take place. The pace and tone are arresting and immediate, down to the use of the present tense.

‘Fish Market’ by Silvia Rose and Ruby Burgin’s ‘Kind Red Spirit’ take the reader out of Wales through stories set respectively in Spain and Japan. In ‘Fish Market’ we have a skilled narrator creating an atmospheric sense of place in a sensual and deeply moving tale of impending loss during a couple’s mini-break in a Spanish city. Burgin’s ‘Kind Red Spirit’ is a contemplative story of grief and ultimate acceptance. I loved the symbolism, dripping with colour, and the way the writer moves effortlessly from realism to magic realism within a controlled narrative arc.

‘Second to Last Rites’ by Ruairi Bolton employs classic oral storytelling techniques alongside contemporary stylistic features. The story explores the liminal space between life and death, as well as the relationship between grief and memory, with a good dollop of rare and much-needed humour.

‘Sunny Side Up’ crafted by JL George, takes Rhys Davies’s birthplace of the Rhondda and fast-forwards it to the day of Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral in 2022. Set over breakfast in a café, this is a visceral and political dissection of post-industrial south Wales seen through the eyes of a disaffected and disillusioned young man, Billy Ferretti, an ‘outsider’ in his own community. This is mature, polished and informed writing.

I selected ‘Harvest’ by Matthew G. Rees as my winning 5story. It takes the reader deep into the territory of the short story as exemplified by Rhys Davies. Here we see a man exiled by his belligerence, attempting to hold back time’s march. The liminal space of the cockle-beds is not a mere backdrop, but a living, breathing habitat for Cock Davies to enact his final almost Biblical denouement and act of self-destruction. The narrative structure is controlled, the language archaic and delicious, the voice distinctive.

Thanks to the Rhys Davies Trust and the Rhys Davies National Short Story Competition, these dozen stories will be able to – and deserve to – be read by the many. Their authors represent the wide range of confident, accomplished and diverse modern-day voices that have presented themselves in 2023. I’d like to think Rhys Davies would be pleased with his legacy.6

Harvest

Matthew G. Rees

Gull wing-grey sky, tide sucked lower than his good eye can see, Cock Davies rides his tractor down the slip. Hair wild as windswept saltmarsh, face an arrowhead of fierce-cut flint, his calloused hands clench the wheel of his old, phutting Fordson like crab claws. Silurian charioteer of the sort who fought the Romans. All that’s lacking is the warpaint, as he lands on the sands of the estuary.

And his mood – jounce and rattle of his tow-hooked trailer behind him, black soot clouds storming from his tractor’s steepling pipe – is war-like.

Steamrollering the shells of the strandline, he surveys the estuary for signs of life, especially other pickers. Memory of that morning’s collision with ‘officialdom’ swelling – red-raw – within him, like an unrazorbladed boil.

‘Back again, Mr Davies?’ the girl on the council’s counter had said.

In her sing-song voice, a ring of wonder-come-mockery – to the ears of Davies, at least – that he, Old Cock, had survived another winter and should be there at all.

‘All this ought really to be done online now, you know,’ she’d continued, as he’d pushed his terse note – ‘Hoffwn adnewyddu fy nhrwydded (‘I wish to renew my licence’), D. Davies’ – under her screen.

Visible on the sheet’s upper: the inscription in English as 8decreed by his great-great-grandfather, Solomon Emlyn, lauded cockler of the Davies line, possessor of the beard of an Old Testament prophet, and the most expert ‘in-the-field’ (rather than mere academic) authority, to those who knew shellfish, in the whole of the land of Wales.

FinestWelshCockles.Since 1750.

The words said only what was needed, as was the Davies way – and in a font and tar-darkness that offered no compromise.

Along with the note: Davies’s payment – a sum the signing away of which had caused him to wince.

‘Paying by cheque, is it?’ the girl had asked, as if – to his ears – this was some huge inconvenience… as if he’d proposed settlement in shillings and crowns, or with a sewin still dripping, rabbits (limp of neck) and widgeon, warm, bill-bloodied and lead-flecked.

The girl had continued: ‘Card facilities areavailable on our app, Mr —’

At which point, he’d intervened. ‘That’s the right money,’ he’d said of his cheque. ‘To the penny. Don’t you worry about that.’

On the screen – bilingually – between them was a notice that annoyed him: ‘WE WILL NOT TOLERATE ABUSE OF OUR STAFF’.

This was new, Davies thought. He had no recollection of it from previous years.

And it seemed to Davies as if it had been put there for him… as if they – the bloody bureaucrats – had known he’d be coming… renewing – cockling’s equivalent of the stitchwort of the coastal swards… the sharks that newspapers said basked off the bay come summer… the rheumatism that returned to his knees with the autumn rains… the chilblains that troubled his fingertips and toes in winter frosts. 9

Feeling the obligation, his onslaught had then begun. ‘Not that the thing is worth having. Licence?! Be damned!! This council has made a desert of that estuary! You can’t move on those sands for pickers. Every Jack and Jill… forking and raking. Like ants, they are… crawling all over. Destroyed, those beds have been. Over-harvested! All thanks to this place. The cockles have never had a chance!’

Davies had wanted to say how – up in England – there was a term for what was left of the beds now, after the pillage and the plunder: Cock All (not that he had ever been to England… this phrase being merely a scrap of the kind that, when encountered, he was prone to seize on – like some angry cat or scavenger gull).

He’d held back on his language though, sensing he’d said enough. Enough to get a letter of the kind he’d had before, written by some soft-handed, collar-and-tie, warm radiator-in-my-office, cup-of-coffee-on-my-desk, parasitical managerial type. Taking home sixty thousand – to be sure. Who knew nothing about cockles, of course.

‘You have my address,’ Davies had – instead – said (for the delivery of his permit… and – if need be – the idiot letter from the ‘executive’ too timid to speak man-to-man). ‘We’ve been there two hundred and seventy years, if not longer.’

And then he’d walked out to where he’d left his tractor – in some damn fool official’s space – in the car park.

There may be rain, Davies thinks, riding over the sand. The sky has ‘the look’. Although a drop has yet to fall, he can smell it in the air… taste it on his tongue. Here and there, seabirds catch his eye: an egret on the edge of a channel; a low-flying cormorant, feathers mere feet from the flats. Occasionally, there is a judder from the trailer behind him, on which his tools rest 10and sometimes bounce – his shovel, his rake, his sieve, his sacks. That disturbance (and the engine of the Fordson) apart, he relishes the silence – and stillness – of the sands. Their empty infinity calms him. Here he is both alone andat home… with his kin. On such days, he not infrequently sees their ghosts: women in aprons and shawls, whiskered men with horses – or donkeys – and carts; all toiling quietly, save perhaps some words in Welsh, an equine snort or whinny. And then gone: taken by sea fret… some shimmer of sun.

Suddenly, from his Fordson’s worn-smooth seat, Davies sees figures… rival pickers… assembled on a bank. And not any bank, but one of ‘his’. They also have seen him… and cease raking.

They eye him.

In Davies’s eyes: bandits; mercenaries; the ragtag irregulars of some marauding army.

He wonders why, on this particular expedition, he hasn’t noticed them till now… and worries for a moment about the sharpness of his senses.

He attributes the failure of his antennae to the nonsense with the council, the pain of the cheque – the tithe unfairly (as he sees it) exacted so that he might be here, on his ground.

Before now, he and they – the other pickers – have had words. ‘These are my beds,’ he has told them, with anger and spittle (in English as well as Welsh).

But they have stood their ground. Outnumbered, he has retreated.

And now, resting on their rakes and forks, they watch him… as if wondering what he will say, or do, next.

This stand-off is conducted at a distance: Davies having halted the Fordson, so that it idles, roughly, beneath him.

He sits there: high, lean, territorial, like some ancient, starved heron of the shore.

A breeze tugs at the loose flaps of his oilskins.

Although angered by their ‘piracy’ (as he feels it to be), he is aware that they are many and that he is one (even allowing for the reputation that he knows rides with him). Besides, he has heard – before now – of clubs, knives and even guns being drawn.

He lets out the clutch of the Fordson, gives them wide berth, rides on (consoling himself that he will find better beds, bigger cockles, and that to do so is his birthright; it is in his bones, his blood).

In truth, though, he has doubts. In his mind, the words Ionwen Pryce used of his last batch (in a phone call from her stall at the market): ‘On the small side this week, Mr Davies.’

After her, he hears the voice of his great-great-grandfather, Solomon Emlyn – who Davies never knew, but who speaks to him in dreams. ‘Ein cocosniyw’rgorau,fachgen.Cofiahynny.’ (‘Ourcockles are the best, boy. Remember that.’) These words uttered now not in a tone of reminding but of chiding, as if Davies has been failing his forebears, as if ‘S.E.’ – beneath his mossed and lichened chest tomb – has got wind of the grumbles of Ionwen Pryce.

All of which now causes Davies, albeit somewhat apprehensive over his reserves of diesel (and a possible change in the weather), to drive deeper into the estuary’s gaping emptiness than he has ever foraged before.

Rags of blue and white reveal themselves, like ill-strung laundry, in the otherwise slate-coloured sky. Conscious of his remoteness, Davies is encouraged by the seeming brightening 12of conditions, wary as he knows he must be of the peculiarity of the estuary and its world. ‘Out there’ lay no shelter. The sands were like Mars, his father had once warned him: a capricious climate all of the estuary’s own. One cockler – long-buried in a coastal yard – had been struck dead by lightning. Burnt to a cinder, so help him, where the poor fellow had stood – a human rod to that furious fork… there… on the sand. All that remained: his rake’s charred iron – this, rather than any human flesh and bones, being buried in his coffin in the wind-scarred cemetery of that bitter-cold church on its cliff.

His spirits buoyed by the sunlight spilling over the shoulders of clouds, Davies, in the saddle of the Fordson, veers yet further from the slender and disappearing shore. He crosses flatlands, ascends and descends sandbanks, fords channels of fresh and saltwater – his air redolent of a lone prospector, driving a waggon on some old-time – and less trodden – Western trail.

On a wet and non-descript flat that is more mud than sand, Davies suddenly stops… miles, even leagues, from the shore.

There are no outward, above-ground, signs – no ‘casts’ as with lugworms, no ‘keyholes’ as with razor clams, nor even any shells that have been split open and abandoned by birds.

But, in his bones, Davies knows.

For several moments, he simply holds still.

Then he arcs the Fordson around.

As he does so, he looks back at the coast… or where he thinks the coast must lie. Its seam is now so narrow as to barely be the line of a baited hook; its houses and buildings – the church, the chapel, Idwal Evans’s garage, The Admiral’s Arms (in its paint of bird’s egg blue) – mere pinheads, if that. 13

Davies feels sure no one has ever been this far out, but he looks left and right, even so… eyes alive to anything that might move.

His thumb and forefinger (needing no guidance: they know their way) turn the ignition key to ‘Off’.

Faintly, very faintly, Davies’s ears – his lobes ugly, leathery, weather-bitten things – hear the falling of waves… a sound that, given the uncommonly deep retreat of the sea on this section of coast, tells him he is distant from dry land indeed.

The remoteness of the shore means that it is difficult for him to make a precise fix on his location. But he knows that he has left the estuary’s throat… maybe also its mouth… with the possibility that where he now lies is – save for him – the unfilled bed of the sea.

He twists in his seat and peers for water… discerning, with the aid of a break in the cloud cover, a distant and copper-like llyn, which – as the sky above it alters – flashes then vanishes, as quickly as it has appeared…

Davies dismounts the Fordson.

Saltwater spits from beneath his old boots.

Fleetingly, a rainbow (or part of one) shows.

Not someone normally given to romantic thought (a man more of clouds than silver linings), Davies takes its rings for a portent: the possibility that – alone as a rock stack whose monument has been shunned by seabirds – he may be standing on buried treasure.

Davies begins with two boards that he takes from the bed of his trailer. The centimetre or so of seawater above the sand suggests he may not need them (since any cockles – if shellfish there should be – will be sited near the moist surface). But he decides that, having brought the boards, he 14will deploy them. He lays them down flat, then walks on the wood… in something approaching a dance (his disturbance – hopefully – ‘waking’ what he thinks awaits him… down below).

More so than on other days, there is something self-hypnotising in his shuffles and his strides.

At first, all is normal enough. But, to his escalating unease, his ‘jig’ seems to conjure voices. The tones are those of women… women he knows from old pictures: cockle-sellers.

His turns and his stamps elicit strange, siren calls. Who will buy our cockles? Who will buy? Who will buy?

And Davies – seldom less than certain, imperious even, on these sands, hislands – is unnerved. A single – and singular – man, he has always been wary of women – mindful, in a tight-lipped way, of tales of sailors who’ve fallen among mermaids… to wake in the clutches of hags.

He spins round, as if to surprise would-be assailants – perhaps the pirate pickers, who might have followed him at a distance, concealing themselves in channels, lying low behind sandbanks.

Spinning and stopping… and spinning again, he is like some distempered dog in pursuit of its tail.

For all his agitation, he sees nothing… except a few tongues of mist and the empty, and seemingly unending, flats.

Davies does what he can to compose himself, wondering whether he might not be ‘losing it’ (in the way he has heard of lonely men: keepers of lighthouses, shepherds of mountain flocks).

He raises his hands and ruffles such scant slack that exists in the flesh of his face (his skin is dry and trimmed tight, like a wind-scoured strip of old sail).

Lowering his palms, he looks up at the sky. 15

Never one to have worn a wristwatch (the tides, moon and sun have always been his clocks), his eyes search for the latter’s orb… or some sign of it.

With effort, he locates in the grey and whale-heavy heavens a ragged rockpool of light.

Its position tells him the sun is dipping… that the hour is well past noon. This knowledge causes him to wonder how far he has come, the wisdom of what he has done (and is doing).

‘Rhaidimifrysionawr,’ (‘I must hurry now,’) he tells himself. ‘Mae’rtywodynllithrotrwy’rgwydr.’ (‘The sand is slipping through the glass.’)

In appearance, his rake is an ugly, hideous thing: a sort-of outsized cockerel claw of three pig-iron prongs that curve cruelly inwards, its neck the socket for a staff of some uncertain wood that rises crooked as the climb of a mountain goat, and whose colour has become coal-like. Never mind how the years have polished eel-smooth its knobbles and its knots, it seems to have ‘eyes’ that lurk on – and look from – its long, black rod. A tool to uncover cockles, to be sure… and one that, if need be, could (comfortably) maim – and even kill – a man.

This ‘instrument’ is the source of the nickname by which Davies is known (to those other pickers whose families are sufficiently ancient and engrained in the estuary for him to half acknowledge).

Ceiliog.

In English, a coincidental truncation of that which he seeks: Cock.

Not that there are many who have actually seen the relic. Wise as it may be deemed notto work the sands alone, Davies always has… there seeming something of the farmyard fowl about his shape, his manner, in the eyes of those who’ve 16glimpsed him: dark, distant, a belligerence barely suppressed, an inborn need to rule the roost. You wouldn’t pick a fight with an old bird like Davies. Never mind his moulted feathers and his mounting years, his spurs were still scythe-sharp.

To him, his trident is sacred. There is no older rake on the estuary. It has been willed down through history, from one Davies to the next. When he holds it, he has the conviction that not even Old Neptune is his equal. For heis Cock Davies… sea lord… suzerain… king.

He removes it from the trailer with reverence… as if it were the wand of Myrddin, the sword of Arthur, the golden cane of Henry Tudor, the furled umbrella of David Lloyd George. Having done so, he steps solemnly to the scene of his cockle-dance… on the crust of the sand and the mud.

A prayer of a kind – ‘Am yr hyn yr wyf ar fin ei dderbyn…’ (‘For what I am about to receive…’) – passes over his lips, thin as the marram that spikes dune summits… dry as old bladderwrack heaped high on the shore.

And now, from above his head – beneath a Turner seascape sky, a shade darker than those of the artist’s eighteenth-century tours – he swings down his claw… into the sediment.

The entire estuary seems to shudder.

With a drag of the rake, Davies uncovers the first cockle… albeit its nature does not initially suggest ‘shellfish’.

Its freakish size causes Davies to presume it a pebble, or even, bizarrely, a potato.

Only on lifting it and wiping away the surrounding sand and muck does he see, and register, the shells.

He looks again at what he holds, rubs it anew… sees the ribs… feels the beak… stares at it, in wonder.

The find occupieshis palm… like a soap bar. 17

It is the largest he has ever seen.

From his oilskins, Davies – who is quite dumbfounded – manages to draw a pocketknife.

Like his rake, this is an heirloom that has been passed down, from one Davies to the next. Its handle: narwhal horn, so earlier Davieses have sworn (though his suspicions have long been of the headwear of a four-legged field-dwelling beast).

It bears a grimed scrimshaw of a ship’s ringlet-haired figurehead – this being the closest Cock has ever come to holding a woman (an indifference that may be mutual); the estuary has been his wife… his life.

He pulls out a grey and far from sharp sheepsfoot blade, whose bevel and back show scars of long service. He works its end into the cockle, sawing at the fibrous ligament between the shells.

These are reluctant to separate. But, in time, and with persistence, they part.

Davies now quickly puts away the knife and continues to prise, with his fingers and thumbs.

Like the case of some seized and rusted pocket watch, the shells, finally, yield.

Davies is astonished by what he sees inside. For his eyes – rimmed red by the rub of decades of sand grains and sea salt – meet not the small morsel of flesh to which, in more than half a century of cockle-picking, as boy and man, they have grown accustomed, but something that lies spread… like a breakfast egg – a goose egg in girth, at that… and sitting as if in a pan; its ‘yolk’, it might be said, imbued with the most glorious golden glow.

It’s as if Davies hasn’t raked a mere cockle from the estuary’s bed but has reached up and raked down the sun. 18

Davies considers it with awe. He wonders if his ancestors ever saw such a thing. He decides that they couldn’t have, for what he has found, he tells himself, is the mollusc equivalent of the kind of diamond that bejewels a maharajah’s crown… a match for the most fabulous nugget of any goldminer’s fevered dreams.

He wonders what to do with it.

He again looks around him, over the sands… sees that they lie empty, as before.

There can be only one course of action, he decides. Besides: the cockle (prised open, as it has been) will be dead, ‘unfit’, by the time he has returned to dry land.

And so, he raises the shell to his lips… and he fingers its moist flesh into the cragged sea cave of his mouth.

Some are cautious about shellfish, especially the eating of them ‘raw’. But, on that count, Davies has no worries. His is the gullet of the sea crow, the iron stomach of the shark.

Fear, anyway, is uncalled for.

For it is the finest cockle that Davies has ever tasted – that any man can ever have tasted. To his mouth and his mind: a symphony of sensations defiant of true description, but… soft as a barn owl’s down, meaty as a shoulder of mutton, and possessed of the tingleof a mountain trout, as it plays among the tobacco-brown stumps of his teeth and swims over the shallow dams of his shrivelled gums.

It is molten gold in his maw.

The swallowing of it – ‘Dduw, Melys!’ (‘God, Sweet!’) – brings an ecstasy. It is as if his whole being undergoes a miraculous alchemy: a gorgeous, deity-given delight that sweeps through him, to the tips of his fingers, toes, wrinkled nose, and member. He feels himself immortal… god-like, in that paradise of the sands. 19

But then, as if he has stood witness to the most wonderful sunset, the elation ebbs. And he is seized by a sadness: that such a moment shall never be repeated… that he will never see – or taste – a cockle of its like again…

Sensing that its shells shall become treasure (an heirloom, like his knife and rake), he stows them in a pocket of his oilskins – proof, if challenged (not that there are many on the estuary who dare to cross Ceiliog), of the veracity of his tale.

For several moments, he stands, as if spellbound, on the immense sedimental plain.

Then he raises his claw to the heavens… and brings it down again.

To Davies’s amazement, the draw of his rake uncovers a crop of cockles equal in size – and perhaps even larger – than the first.

He falls to his knees in disbelief.

He scrabbles… lifts them to his eyes, as if surveying Spanish doubloons.

Pam?(Why?) he wonders. Sut?(How?)

Arbethmaennhw’nbwydo?(On what do they feed?)

He tries to make sense of how this hoard lies here