Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

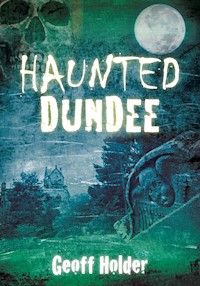

This fascinating book contains a terrifying collection of true-life tales from in and around Dundee. Featuring stories of unexplained phenomena, apparitions and poltergeists, including the tale of the White Lady of Coffin Mill and Balgay Bridge, the hauntings of the historic ships Discovery and Unicorn, and a host of modern ghost sightings - this book is guaranteed to make your blood run cold. Drawing on historical and contemporary sources and containing many tales which have never before been published, Haunted Dundee will delight everyone interested in the paranormal.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 188

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Acknowledgements

LIBRARIANS are authors’ guardian angels, and I would like to express my profound thanks to the staff of the local studies sections of the A.K. Bell Library in Perth and the Wellgate Library in Dundee, and further thanks for permission to reproduce various historic images. For assistance, co-operation and for answering my pesky questions, my gratitude goes out to: Lisa Douglas, Debbie Rooney, Kevin Connolly and Mary Archibald at Verdant Works; Dundee Heritage Trust; South Georgia Heritage Trust; Bob Hovell, Ship Manager, HMS Unicorn; playwright Kevin Dyer and theatre director Michael Judge; tour guide Anthony Cox (www.taysidehistoricaltours.com); Murdo Wilson at Claypotts Castle; and Marek at Dundee Backpackers Hostel.

I am especially grateful to all those who shared their personal stories with me, including: June Kelso; Colin McLeod; Sarah Fraser (with extra gratitude for granting permission to reproduce her sketch); and Victor and Elena Peterson of Mains Castle. None of their stories have previously been published. The Ghost Club investigation, led by Derek Green, gave me the opportunity to explore RRS Discovery under unusual circumstances. Ségolène Dupuy did wonders on the photographs and Jenni Wilson drew the maps.

This book is a companion to the author’s Paranormal Dundee (2010) and is part of a series of works by Geoff Holder dedicated to the mysterious and paranormal. For more information, or to contribute your own experience, please visit www.geoffholder.com. And say hello to webmaster Jamie Cook while you’re there.

To Shade and Slick – companions both. Now go and lie down and let me work!

Contents

Places to Visit

Introduction

one The White Ladies

two Contemporary Encounters with the Supernatural

three Malevolent Entities

four The Den o’Mains

five Spooky Ships – Discovery and the Frigate Unicorn

six Fakes, Frauds & Folklore – and Spring-Heeled Jack!

seven ‘Traditional’ Ghosts

eight Historic Hauntings

Bibliography

Places to Visit

The following locations are open to visitors:

Claypotts Castle/Castle Gardens: Claypotts Road, DD5 3JY. View exterior only. To visit interior, call 01786 431324 in advance. Admission free. No internal wheelchair access.

Discovery Point Visitor Centre: Discovery Quay, DD1 4XA. Tel: 01382 309060. www.rrsdiscovery.com. Open Monday–Saturday 10 a.m.–6 p.m. (Sun 11 a.m.) from April to October; 10 a.m.–5 p.m. rest of year (Sunday 11 a.m.). Admission charge. Wheelchair access throughout museum and to main deck of the historic ship only.

Dundee Backpackers: 71 High Street, DD1 1SD. Tel: 01382 224 646. Public access (including wheelchair access) to display area in inner courtyard only. Admission free.

The Frigate Unicorn, Victoria Dock: DD1 3BP. Tel: 01382 200900. www.frigateunicorn.org/. Open 10 a.m.–5 p.m. all week from April to October; November to March: 12 p.m.–4 p.m. Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, and 10 a.m.–4 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Admission charge. Wheelchair access to Gun Deck only.

Verdant Works: West Henderson’s Wynd, DD1 5BT. Tel: 01382 309060. www.rrsdiscovery.com. Open Monday–Saturday 10 a.m.–6 p.m. (Sun 11 a.m.) from April to October; 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday rest of year (Sunday 11 a.m.). Admission charge. Wheelchair access throughout museum (note courtyard is cobbled).

Mains Castle welcomes enquiries for weddings and corporate events: www.mainscastle.com. The castle is not open to the general public.

Many of the other locations mentioned in this book are private; please respect the privacy of the residents.

Introduction

ON my shelves are two classics from an earlier generation of ghost books: The Ghost Hunter’s Road Book by John Harries, which came out in 1968 and has more than 400 entries across Britain, and Haunted Britain by Anthony D. Hippisley Coxe, published in 1973 with over 1,000 entries covering England, Wales, Scotland and the Isle of Man.

Dundee is not mentioned in either of them.

Neither does Dundee feature in more modern supernatural surveys, such as The Ghost Tour of Great Britain: Scotland by Richard Felix (2006), Roddy Martine’s Supernatural Scotland (2003) and Haunted Scotland (2010), the huge Readers’ Digest work The Most Amazing Haunted & Mysterious Places in Britain (2009), and Derek Acorah’s Haunted Britain (2006). As far as ghost-hunters are concerned, it appears that Dundee is not even on the map.

But, as the man said, it ain’t necessarily so, and Dundee has been unjustly ignored. In this book you hold in your hand, this oversight will be corrected. We are about to explore several centuries of Dundonian hauntings. Here you’ll find stories of poltergeists, malevolent entities, apparitions, strange sounds, doppelgängers, visionary experiences and much more. The incidents range from 1706 to the present day. There is also, you should be warned, a wholesale demolition of some of the city’s best-loved traditional spectres. And you will find a full stock of fakelore and frauds, for the tendency to hoax the supernatural is always with us. In 2011, for example, there was an attempt in the local press to suggest that a particular stone in the old graveyard of the Howff was a memorial to Grissel Jaffray, who was executed for witchcraft in 1669. I covered Grissel’s trial extensively in my previous book Paranormal Dundee, and it is quite evident that the ‘memorial’ episode is not just bad history, but a naked attempt to foist a fake story onto the public. Beware of false paranormalists, my friends.

Other than those stories personally related to me, the episodes in Haunted Dundee were taken from a variety of published sources, such as books, academic journals and websites, all of which are credited in the text. The bibliography allows anyone interested to go to the original sources and see if they agree with my interpretation. Many of the older stories in this book have not seen the light of day for well over a century, and most were found in old newspapers. Dundee’s two principal papers have a confusing history. The Dundee Weekly Advertiser which launched in 1801, later beame the Dundee, Perth & Cupar Advertiser and finally the plain Dundee Advertiser from 1861. The Dundee Courier commenced publication in 1817 and, at various times in its history, was known as the Constitutional Dundee Courier, the Dundee Courier & Daily Argus, the Dundee Courier & Argus, and the Dundee Courier & Argus and Northern Warder. In 1926 both papers merged to form the Courier & Advertiser. To keep matters simple I have used the single names Advertiser and Courier for the older editions, and the title Courier & Advertiser for all stories after 1926.

A postcard of a typical Dundee scene from 1905. (Author’s collection)

Dundee High Street in 1906. Many of the buildings shown have since vanished. (Author’s collection)

Up until the seventeenth century, Dundee was Scotland’s second city after Edinburgh, a dynamic and prosperous seaport with trading links across northern Europe. In the late 1700s, the economic focus turned to industry, primarily textile production. Soon dozens of mills were processing flax brought from the Baltic. The population doubled, then doubled again, then rose exponentially as people flocked in from the countryside. From the 1850s, the dominant industry was jute production, a coarse but versatile fibre imported from India. Dundee became a city almost exclusively devoted to textile manufacturing. Jute spinning and weaving employed 40,000 workers across 125 mills, while linen production continued to employ thousands more. A forest of 200 tall chimneys greeted visitors, with a dense ring of industry encircling the city centre and docks. In a (successful) effort to keep wages down, exploitative employers favoured women and children as mill workers. Working-class housing and living conditions were appalling, and Dundee became something of a classic Victorian sinkhole. In the twentieth century, jute went into terminal decline, and in the post-war years the city has struggled with the effects of post-industrial collapse and urban decay.

Despite all this, the medieval and Renaissance hodgepodge of the city centre remained largely intact until 1871, and, if circumstances had been different, Dundee would have been an architectural gem today, on a par with Edinburgh’s Old Town. But a combination of political infighting, financial problems and disastrous planning decisions has swept away the vast majority of Dundee’s historic buildings. As will be clear from the cases studied here, this has had a profound impact on what might be termed the city’s haunted heritage.

Welcome to Haunted Dundee. It’s back on the map.

We folks wha occupy these coasts

And pride oursel’s on our discernin’,

Are no gien to belief in ghosts

They tally not wi’ our book-learnin’;

Wraiths, warlocks, bogles, how we jeer them

And yet, in truth, the maist o’s fear them!

‘The White Lady of Claypotts Castle’ – Joseph Lee

one

The White Ladies

BRITISH ‘ghost-lore’ is dominated by certain kinds of female apparitions. There are endless Green Ladies and Grey Ladies, with slightly fewer Pink Ladies – all named for the period costume they are usually seen wearing. White Ladies are also populous, and Dundee has at least four examples.

The White Lady O’ Balgay Bridge

Q: Do you feel safe in your area?

A: I do feel quite safe in my area. Your [sic] fine as long as you avoid the cemetery at nights so you a) don’t get scared by the mysterious souls that skulk around the graves and b) don’t get eaten alive by the ghost that patrols the white lady bridge.

This was one of the responses to the ‘You & Your Area’ survey conducted by Young Scot Dundee from September to December 2006, and held online at www.youngscot.org/dundee and www.dundeecity.gov.uk.

Over 500 eleven to fifteen year olds took part. Most responded to the question regarding safety by mentioning concerns over gangs, junkies, drunks, graffiti and other urban problems. This particular pupil, however, concentrated specifically on the terrors of the White Lady of Balgay Bridge.

Balgay Bridge is the cast-iron Victorian footway that stretches high over the ravine of the Windy Glack, connecting the recreational woodlands of Balgay Hill to the east with the tree-lined footpaths of Balgay Cemetery further west. Widely known among the residents of the Lochee area, and a favourite childhood spook, the White Lady features in a number of different stories:

She is seen reading a letter then bursting into tears before disappearing – or jumping off the bridge.

She runs from the bridge into the cemetery, weeping.

She can be summoned at midnight by walking across the bridge three (or five, or seven) times.

She can turn those who unwittingly summon her into a pool of blood.

She can eat people alive (see above).

She can push unsuspecting bystanders off the bridge.

She is heard screaming at midnight as she plunges to her death.

She is rarely seen, but her crying and footsteps are often heard, and dogs grow nervous at her invisible presence.

Balgay Park in 1907. Note Balgay Bridge in the background. (Author’s collection)

Balgay Bridge today, taken from the Windy Glack. (The Author)

Wonderfully evocative stuff, I’m sure you’ll agree, combining traditional elements of the ghost story with aspects that are distinctly demonic (and with a clear hint of Clive Barker’s Candyman). There is just one problem with this rich skein of supernaturalism – there are no reliable accounts for any of it. Stories there are in abundance; sightings, however, are conspicuous through their absence. The White Lady exists in a web of rumour, thrice-told-tales, anecdote, ‘foaftale’ (friend-of-a-friend tale), childhood recollections and urban legend. In other words, she is a folk ghost.

What follows is a tentative exploration of the factors that may have contributed to this folkloric phantom. As with most areas of the paranormal, it is difficult – not to say foolhardy – to make definitive pronouncements about the absolute black-and-white reality or unreality of specific phenomena. However, given that (a) the White Lady is widely-known and (b) there are no dependable reports, we are entitled to interrogate the context of the haunting to see if anything useful comes out of the combination of analysis and speculation.

The first place to start is the physical environment. The bridge at Balgay stretches for 80ft over the ravine. Crafted out of decorative cast-iron, and recently attractively repainted, it is a striking structure both geographically and aesthetically, and could be said to be in contrast with its immediate setting. To the east is the hill of Balgay Park, a popular recreational area at the centre of Lochee’s green lung, with Lochee Park and Victoria Park stretching contiguously to the north and south respectively. The space was purchased as a public area by the council in 1869, being carved out of the former Balgay Estate. From the very first it was designed as a People’s Park: a working-class recreational area where the half-life of industrial squalor could be temporarily forgotten. A plaque on the bridge states: BALGAY HILL RECREATION GROUNDS PROVIDED BY THE COMMUNITY OF DUNDEE FOR THE USE OF THE PEOPLE, AND OPENED 20 SEPTEMBER 1871. Balgay Cemetery (formerly known as the Western Necropolis) is on the opposite side of the ravine, with the older (late-Victorian) monuments in the north part, close to the bridge. In The Municipal History of the Royal Burgh of Dundee, published in 1873, J.M. Beatts gives his thoughts on the aesthetics of this attractive wooded cemetery:

An hour’s retirement and contemplation in the precincts of these beautiful grounds cannot fail to impress the mind with the idea that both nature and art have combined to render the place most fitting for reflection on the power of the Creator, the shortness of human life, the immortality of the soul, and the heavenly rest beyond the grave prepared for the people of God.

Another view of Balgay Bridge. The entrance to Balgay Cemetery can be seen in the background. (The Author)

The ravine of the Windy Glack always divided Balgay, and so the bridge was built to provide ease of access between the two parts of the hill. From one point of view then, the bridge is a link between the lands of the living and the dead. Such transition places are liminal places, psycho-geographical hotspots where supernatural episodes – or at least stories of supernatural episodes – tend to be concentrated. Liminality, the notion of crossing borders (such as between the mundane world and the netherworld, or between one state and another) is a key concept in magic and myth. Midnight, the moment between one day and another, is a liminal time; ten to eleven is not. Bogs and caves are liminal places, as are parish boundaries, doors, gates, churchyard walls, seashores, tunnels and thresholds. Balgay Bridge is definitely liminal.

It is, of course, also very high, towering 80ft above the (now-paved) ravine below. There is something about such an expanse that, in a small number of people, fosters thoughts of jumping into the void below. The Glack, and the Balgay area in general, had a questionable reputation up until the early nineteenth century, and there are numerous newspaper reports of footpads, smugglers, and assaults on women.

Balgay, then, was a place with a pre-existing reputation for dark deeds. Its physical setting, a ravine between two hills crossed by a strikingly designed bridge, is impressive and unusual. Part of the bridge leads directly to a cemetery. Since becoming a park the area is both popular and, because of the woodland, secluded. And there is a question of whether the massive iron structure of the bridge somehow channels or deflects an electromagnetic field – and EM fields are known to have an impact on human cognition, including influencing perceptions of apparent supernatural events. All these factors contribute to a sense that Balgay Bridge is psycho-geographically potent; a place where things can happen.

That, in itself, may not be enough to generate a haunting. Balgay, however, also has a known history of tragedy and violent death, all grist for the mythic mill.

Only one accidental death is on record. On 21 March 1846, the Scotsman reported that a blacksmith, James Ferrand, had been killed by a landslide at Hillside Quarry on Balgay Hill – but the area soon had its fair share of suicide attempts (and, you will recall, the White Lady is, at least according to some versions, supposed to throw herself off the bridge). The first recorded suicide on the hill was that of George Bruce, a weaver from Henderson’s Wynd, who was reported in the Advertiser as being found dead on the morning of 6 September 1837. On 15 May 1883, the Scotsman reported that the previous day, a drunken woman named Bridget Finney, or Finnie, had attempted to jump from the bridge; her death was only prevented by a groundsman named Hugh Smith who, being deaf and mute, could not call for help, and had to hang on to the thrashing woman until others spotted the struggle and rushed to assist. Four days later, the Weekly News reported that, ‘the woman Bridget Finnie or Mullare … was called in to answer to a charge of drunkenness … She had been liberated on a bail of 5s, and, failing to answer to her name, the pledge was forfeited.’ Two years on, twenty-eight-year-old James Newlands blew his brains out with a single shot to his temple (the report was in the Courier on 30 January 1885); in 1894, thirty-seven-year-old William Jarvis Parker sat on his family burying-place in the cemetery and put two bullets in his head (Courier, 24 September); and finally, fifty-two-year-old Roland Smith threw himself off the bridge in 1898 (Courier, 27 June).

Is this where the White Lady patrols? (The Author)

One of the Victorian gravestones in Balgay Cemetery. (The Author)

But none of these tragedies provide us with a link to the White Lady, who, according to the standard tale, was both determined to die and determinedly female. There are, however, two possible candidates for the source of the legend: Janet Fenton and Christina Fraser.

Janet Fenton’s demise was reported in the Scotsman on 10 November 1882:

Yesterday morning a widow named Fenton committed suicide by throwing herself over a suspension bridge in Balgay Public Park, Dundee. She fell a distance of 30 feet and was killed on the spot, her body being terribly mangled. The woman’s mind was affected since the loss of her husband, a mechanic, who was scalded to death in a Dundee millpond several years ago.

Logie resident Janet was fifty-nine years old, and left behind seven children. The Courier, for 15 January 1875, described how her husband, James Steel, had suffered an appalling death after falling into a hot-water tank at the South Dudhope Works.

As for Christina Fraser, her sad death appeared in the Advertiser on Wednesday, 17 May 1911:

The woman who fell from the bridge in Balgay Park on Friday succumbed to her injuries yesterday in Dundee Royal Infirmary. Two boys, cycling through the park shortly after six o’clock in the evening were startled to see a woman hanging from the high bridge. Before they could reach the bridge to render assistance the woman relaxed her grip, falling to the steep bank below and rolling onto the path. When picked up she was still alive but unconscious, and was removed to the Infirmary, where she was identified as Christina Fraser (53), millworker, who resided with her brother and sister at 69 Ure Street. Her injuries were of a serious nature, but she lingered until yesterday.

The Scotsman for the same day added another detail:

Recently the bridge was securely fenced because of the number of deaths connected with it, and how the woman managed to get on the outside is as yet unexplained.

So, White Lady-wise, this is what I suggest happened. The Balgay area had an existing reputation, compounded by a rake of tragedies and dramatic events, and further focused by the striking and at times eerie situation of the bridge. The location’s locus as a suicide spot became the overarching narrative, with just the right coup de grâce provided by the awful deaths of Janet Fenton and Christina Fraser. Out of this rich stew of dark events and grim geography, the place garnered a ‘no’ canny’ rep, and the White Lady was born. Perpetuated by generations of children, the ghost story became further elaborated and expanded, so that soon everyone knew it was ‘true’, simply because it was so widespread. Of course, I could be utterly mistaken, and the next time I stroll over the bridge a rather miffed spectre may come and give me a piece of her mind; but for my money the White Lady O’ Balgay is a figment of the folk mind, a Lochee legend.

The White Lady of the Coffin Mill

Hundreds of people gathered in Lower Pleasance last night when it was reported a ghost called ‘The White Lady’ appeared…

Such was the opening line of an article in the Courier & Advertiser on 5 September 1945, headlined: ‘GHOST WALKS BRIDGE – DUNDEE THRONG VISITS SCENE – “THE WHITE LADY” OF COFFIN MILL.’ According to an unnamed elderly woman who was interviewed by the newspaper, the phantom was the spirit of a mill girl who died when her long hair became trapped in a loom and she was crushed to death. Again according to this anonymous local witness, the accident had occurred in the first week of September ‘seventy years ago’ – and the ghost periodically returned, pacing the enclosed exterior bridge that connected two parts of the mill. So large were the numbers gathered, that at 10 p.m. that the police arrived and told the crowd to disperse. Some did so, but many hung around the adjacent Brook Street in the hope of seeing the ghost. The article went on to say that:

To satisfy the public that everything was normal, a police officer had a street lamp lit at the junction, which resulted in the crowd going from Brook Street into Lower Pleasance. Many of the younger folk in the crowd began throwing stones at the windows, causing a lot of damage. The street was littered with broken glass, and for some unaccountable reason other people broke milk bottles on the causeway at the entrance to the mill. To fully satisfy the crowd there was no ghost, a police officer, accompanied by the works watchman, made a tour of the building shining their torches over every window as they went.

The Coffin Mill, with the White Lady’s bridge. (The Author)

What with a large, unruly crowd, a police presence, and stone-throwing and glass-breaking, this sounds like a near-riot – and all because of a rumour of the return of the White Lady of Coffin Mill.