Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

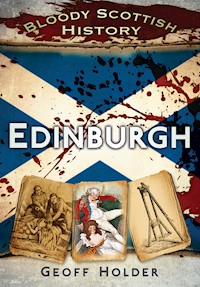

The Little Book of Edinburgh is a funny, fast-paced, fact-packed compendium of the sort of frivolous, fantastic or simply strange information which no-one will want to be without. Here we find out about the most unusual crimes and punishments, eccentric inhabitants, famous sons and daughters and literally hundreds of wacky facts. Geoff Holder's new book contains historic and contemporary trivia on Edinburgh. There are lots of factual chapters but also plenty of frivolous details which will amuse and surprise. A reference book and a quirky guide, this can be dipped in to time and time again to reveal something you never knew. Discover the real story of Greyfriars Bobby (he was a publicity stunt), meet the nineteenth-century counterparts of our favourite modern detectives, from Jackson Brodie to John Rebus, seek out historical sites from the distant past to the Second World War, and tangle with the Tattoo and freak out with the Festival. A remarkably engaging little book, this is essential reading for visitors and locals alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 235

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To the Auld Alliance, although perhaps not the one you’re thinking of. Allons-y!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As well as the usual writer’s support network (you know who you are), thanks go out to the library angels of Edinburgh Central Library and its Edinburgh and Scottish Collection; the National Library of Scotland; and the A.K. Bell Library, Perth. I’d also like to express my gratitude to the staff of all the museums, galleries, visitor attractions and cafés I visited in the course of researching this book. Oh, the suffering.

The topographical views are taken from Modern Athens, or Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century by Thomas H. Shepherd (1829-1831). All other illustrations are from various Victorian and Edwardian volumes of Punch, with the exception of the images of Burke and Hare, which are courtesy of Cate Ludlow.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. Places – Here & Now, Then & There

2. Rivers, Lochs and Canals

3. Transports of Delight – Trains, Trams, Ferries and Flight

4. Wars, Battles and Riots

5. Crime and Punishment

6. City of Culture

7. The Natural World

8. Sports and Games

9. Edinburgh at Work and Play

Bibliography

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

‘The most beautiful of all the capitols of Europe.’

Sir John Betjeman, First and Last Loves (1952)

‘This accursed, stinking, reeky mass of stones and lime and dung.’

Thomas Carlyle, letter to his brother (1821)

These two quotes perfectly sum up Edinburgh. It is spectacularly beautiful, combining a dramatic natural landscape of hills, valleys and the cone of an extinct volcano with an architectural heritage so glorious that it has more listed buildings than anywhere in the UK outside London. And at the same time there is a grimness to the place, a secret, gritty history of dark deeds and squalor. It is this combination – beauty and the beast, if you like – that makes Edinburgh so utterly fascinating, so beguiling.

One of Edinburgh’s most famous sons, Robert Louis Stevenson, knew this better than anyone. His novel Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, about two conflicting personalities inhabiting the same body, is a virtual metaphor for his native city. Edinburgh is a ‘tale of two cities’, or rather, many different tales. Historically, there are the two cities: the Old Town, a medieval gloom-a-thon of narrow lanes, twisting streets and hunchbacked buildings; and the New Town, an Enlightenment vision of wide, straight streets, elegant crescents and neo-Classical mansions. Take it further, and you literally have two cities – the City of Edinburgh and the Port of Leith, neighbours only formally joined as late as 1920, and still bearing a sense of difference.

Socially, there is the gulf between the intellectual, moneyed and professional classes – who, since the sixteenth century, have made up a major segment of the population – and those at the lower end of the social scale. When Charles Dickens visited, he found the highest levels of sophistication and civilisation operating just a few streets away from scenes of poverty worse than he had found in the East End of London. Today, St Andrew Square and Charlotte Square in the New Town are the most expensive pieces of real estate in Scotland, while some of the peripheral housing estates are wastelands of drugs and gang violence.

How about the duality of hypocrisy? In the early 1800s some of the finest minds in Europe were pushing forward the frontiers of knowledge on the one hand – and on the other condoning grave robbing and even murder. A few decades earlier, Deacon Brodie, town councillor and respectable businessman by day, was, under the cover of darkness, a master burglar and thief.

Even physically, Edinburgh has two parts: up and down. Streets that appear to be adjacent when looking on the map are in fact separated by great cliffs of buildings that can only be negotiated by prodigious stairwells. A street-level shop on one road turns out to be one of the upper storeys of a tenement that has its roots in the urban valley far below. Edinburgh, the precipitous city, is as full of hills and glens as any heather-clad country district, even if the topography is camouflaged by brick and stone.

There is another dichotomy to savour. Not that long ago, Edinburgh was the city of disapproval and distaste, where fun was forbidden and pleasure proscribed. These days it is one of the most enjoyable small cities on the planet, where there is always too much to see and too little time to do everything. It is a city dedicated to culture and excitement, a feast for the mind and the senses. Whether it is delving into the myriad delights of the Festival, or marvelling at the treasures in a museum or gallery, or simply pounding the streets in search of architectural wonders and then settling into a back street café, your experience of Edinburgh is guaranteed to be extraordinary.

And it’s that extraordinariness that has inspired this book. There is history, but this is not a history of the city. There is culture, but this is not a guidebook. There is sport, and the natural world, and the world of work and play, and war and heroism and crime and police. This is a canter through the intriguing, bizarre and wonderful story of this most Jekyll and Hyde of cities.

The feeling grows upon you that this also is a piece of nature in the most intimate sense; this profusion of eccentricities, this dream in masonry and living rock is not a drop scene in a theatre, but a city in the world of every-day reality.

Robert Louis Stevenson, Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes (1878)

1

PLACES – HERE & NOW, THEN & THERE

PREHISTORIC DAYS

Edinburgh has the earliest known human settlement in Scotland. Analysis of hazelnut shells found in the temporary camp occupied by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers at Cramond has produced a date of 8,500 BC, when ice covered much of the country.

Edinburgh also has one of Scotland’s earliest permanent dwellings – a Neolithic roundhouse at Ravelrig Hill near Dalmahoy. The early farm was established about 3,000 BC, roughly the same time as the famous settlement of Skara Brae in Orkney.

A Bronze Age tribe occupied Castle Rock in 900 BC, the first of many peoples who recognised the hill’s defensive position.

WHAT DID THE ROMANS EVER DO FOR US?

Cramond had a Roman fort and harbour. The site produced the sculpture of a lioness eating a man, one of the finest pieces of Roman art found in Britain. The outline of the fort can still be seen beside Cramond Church and the sculpture is in the National Museum of Scotland on Chambers Street.

The National Museum also has a fantastic collection of silver objects discovered on Traprain Law, a volcanic hill in East Lothian. The treasure seems to have been payment from the Romans to one of their client tribes, the Votadini, who also occupied Edinburgh’s Castle Rock. The Votadini had chosen not to resist the invasion and as a result prospered through trade with Rome. After the Romans left, the powerful Votadins, now called the Gododdins, established a kingdom based on their timber fortress on Castle Rock.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

No one really knows the origins of the city’s name. The best evidence suggests that Dun Eidyn or Din Eidyn was the name given to Castle Rock by the Kingdom of Gododdin, ‘Dun’ meaning fort. The Gododdin were Celtic Britons; in the seventh century, when the area was occupied by the Angles (whose language later mutated into English and Scots), the name lost the ‘dun’ element and gained the ‘–burgh’ suffix, from the Old English word ‘burh’ (fort). Medieval versions of the name include Edenesburch, Edynburgh and Edynburghe, and even in the seventeenth century you could read of Edenborough, Edenborrow or Edenburgh.

Modern scholars reject the once-popular notion that ‘Edinburgh’ is derived from ‘Edwinesburh’ (Edwin’s fort), a supposed reference to Edwin, a seventh-century king of the Angles. The Scottish Gaelic version of the name, Dùn Éideann, is a transliteration of ‘Dun Eidyn’, and has led some people to call the city Dunedin.

Vernacular variants include Embra and Embro, and poets have used the term Edina, while the coal-hungry and be-chimneyed city has been known as Auld Reekie (Scots for Old Smoky) since the seventeenth century.

MEDIEVAL EDINBURGH

Edinburgh was a walled city from the late Middle Ages onwards. The King’s Wall, built in 1450, excluded the low-lying Grassmarket, even though the open space, along with the Cowgate, was already an established part of the city.

The larger Flodden Wall, erected in a panic in 1513 after the catastrophic Battle of Flodden to keep the English out (they didn’t come), was more generous, extending further to the south. Fragments of the Flodden Wall can be seen today on Keir Street and in Greyfriars Kirkyard.

For 250 years no one built outside the confines of the Flodden Wall. The population, however, kept rising. The only solution was to build upwards, creating the world’s first skyscrapers, ‘lands’ that at their extreme could count fourteen floors from the lower level of the back lanes on the slope to the wind-blasted upper garret.

In 1636 almost all of the city’s 60,000 inhabitants were living in the Royal Mile and its sixty attendant closes and wynds. The overcrowding was fearsome, akin to a shanty-town or refugee camp of today.

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century destroyed a treasury of church items deemed ‘idolatrous’, such as statues, woodcarvings and stained glass. The only complete stained-glass windows remaining from medieval Scotland can be found in the Magdellan Chapel on Cowgate.

The principal entry through the Flodden Wall was Netherbow Port, which stood at the Royal Mile junction of Jeffrey Street and St Mary’s Street, at the head of Canongate. For many years this marked the boundary of the city of Edinburgh (Canongate was in another jurisdiction), and so the area became known as World’s End. The old world of medieval thinking did end after the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46, and, with armed attack no longer a threat, the Port was demolished in 1764. Brass plaques in the roadway now mark the site of the Port.

The Royal Mile derives its name from the route that stretches from the fortress of Edinburgh Castle (defender of the kingdom and home of the Scottish Regalia) down the slope to Holyrood Palace (constructed in the early sixteenth century as the royal residence in Edinburgh). It is approximately 1 old Scots mile long, about 12 per cent longer than a current statute mile.

NAVAL GAZING

In the fifteenth century the Yellow Caravel, an armed merchant ship belonging to the privateer Sir Andrew Wood of Largo, stranded on a sandbank at the entrance to the port of Leith. As Wood’s two ships were effectively the extent of Scotland’s (semi-private) navy at the time, this lack of safe passage was a major issue. James IV therefore had the tiny fishing harbour of St Mary’s Port, just along the coast, built up into a full-scale facility called New Haven Port of Grace (now Newhaven). Leith’s later docks expansion has obscured the once important role Newhaven played in medieval Scotland.

The year 1511 saw the initial launch of the Great Michael, a huge four-masted man-o’-war or carrack, the pride of James IV’s nascent Royal Scottish Navy. To build the ship and its dock, Newhaven had become Scotland’s premier industrial centre, employing hundreds, and consuming huge swathes of timber (including, it is said, most of the forests in Fife, and all the trees lining the Water of Leith).

Building the Great Michael was the equivalent of constructing the largest aircraft carrier of modern days, and then some. She was the largest warship in Europe at the time. After years of work the carrack finally took up station in early 1513, riding at anchor in the Firth of Forth in the lee of the island of Inchkeith, ready to take on any English raiders. No such conflict occurred. A few months later, James IV was killed at the Battle of Flodden, and a crisis-ridden Scotland sold the hugely costly ship to France at a knockdown price.

CITY OF SEVEN HILLS?

At some point in the eighteenth century, which was obsessed with the Classical world, it became standard practice to refer to Edinburgh as built on seven hills, in the same manner as Rome. Edinburgh certainly has many steep gradients, as pedestrians and cyclists quickly discover. But are there really only seven hills?

The annual Seven Hills of Edinburgh race takes the traditional view. Its seven are:

Calton Hill, just east of the New Town.

Castle Rock.

Corstorphine Hill in the west of the city.

Craiglockhart Hill, Braid Hill and Blackford Hill, all in the south.

Arthur’s Seat, to the east.

Other hills not on this list can be found in the New Town, Dalry, Sighthill and Fairmilehead, most of which are not noticed because they are built over. Fairmilehead, however, at 183m high, is higher than four hills on the traditional list.

The highest point within the city boundaries is Arthur’s Seat. The Pentland Hills just to the south of the city are far higher, but it is Arthur’s Seat’s elevation of 251m that dominates the skyline and helps to provide Edinburgh’s distinctive profile.

OPINIONS ON A GRAND CITY

In 1435 an Italian nobleman arrived on a secret mission to meet King James I, a visit so sensitive that, to his great discomfort, Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini was forced to travel by ship all the way to Scotland rather than risk being taken by the English. After being storm-tossed and being rendered permanently lame by frostbite arthritis through walking on snow-covered roads, Aeneas found Scotland somewhat uncongenial, and noted in his autobiography, The Commentaries, ‘There is nothing the Scotch like better to hear than abuse of the English.’ The pretty women of Edinburgh and environs, however, were a different matter, and the dashing Italian fathered a child during his visit. Twenty-three years later, Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini became Pope Pius.

The pre-Papal visit is recorded in a beautiful fresco within the grandiose Piccolomin Library in Siena, Tuscany. The ‘Oration as envoy before King James I of Scotland’, created by the Renaissance artist Pinturicchio in the first decade of the sixteenth century, shows King James and his court gathered in a sunny Italian portico surrounded by luscious foliage. In reality the meeting took place in the depths of winter in a place Aeneas described thus: ‘A cold country where few things will grow and for the most part it has no trees.’

Throw a stone anywhere in Edinburgh today and you will be in danger of breaking the windows of several hotels, bed and breakfasts, youth hostels and other accommodations for the travel-weary visitor. In the eighteenth century, however, the situation was very different. In 1774 Captain Edward Topham wrote to a friend that, ‘There is no inn that is better than an ale-house, nor any accommodation that is decent, cleanly or fit to receive a gentleman.’ Stopping at what was reputed to be the best inn in the city, Topham was dismayed to discover that he was expected to share bedding with another eight or ten people. He found alternative lodgings on the High Street, which he however said were ‘so infernal in appearance’ that he could have been in a particularly dirty Hell.

‘The city is placed in a dainty, healthful and pure air and doubtless was a most healthful place to live in,’ wrote Sir William Brereton in 1634. The English visitor gloried in the architecture and setting of Edinburgh, but he was less than impressed by the eye-watering, nose-holding stench, adding, ‘were not the inhabitants most sluttish, nasty and slothful people.’

The much-mocked nineteenth-century poet William McGonagall, in describing the Grassmarket, quoted Mark Twain’s opinion on an Italian city: ‘The streets are narrow and the smells are abominable, yet, on reflection, I am glad to say they are narrow – if they had been wider they would have held more smell, and killed all the people.’

Virtually every eighteenth and nineteenth-century visitor to Edinburgh remarked on the city’s awful smell. Given that many of these visitors came from London or Glasgow, themselves places hardly gentle on the nose, Edinburgh must have truly stunk to high heaven.

Georgian Edinburgh was, however, widely recognised for the quality of its intellectual life. ‘Here stand I,’ said Mr Amyat, a London visitor, ‘at what is called the Cross of Edinburgh, and can in a few minutes take fifty men of genius by the hand.’

Others have been less kind. The religious fanatic and Covenanter Patrick Walker denounced the city as: ‘Sinful Edinburgh, the Sink of Abominations, that has defiled the whole Land, where Satan sometime a Day had his seat.’

EDINBURGH’S CASTLES

Edinburgh Castle on Castle Rock is one of the most famous fortifications in the world, and the city’s Number One tourist attraction. There are, however, a number of less famous castles dotted around the city.

Merchiston Castle or Tower sits amidst Napier University’s Merchiston campus. Built around 1454, the tower was damaged in 1572 during the war between rival supporters of Mary, Queen of Scots and her son, the future James VI. Restoration work in the 1960s uncovered a 26-pound cannonball embedded in the tower wall.

Napier University has a second castle, although the tower house of Craiglockhart Castle on Craiglockhart campus is quite ruinous.

Liberton Tower in the suburb of the same name is a fairly plain tower house in good condition.

Cramond Tower, a restored seventeenth-century tower house in Cramond village, is a private residence, as is Barnbougle Castle west of Cramond. Barnbougle’s medieval structure was entirely rebuilt in Scots Baronial style in 1881.

Bavelaw Castle is another restored structure in private hands, this one southwest of the city.

Lauriston Castle, between Cramond and Davidson’s Mains, is open to the public, and has lovely grounds.

The much-altered Craigcrook Castle in Blackhall mostly dates from the seventeenth century, and in later times hosted a variety of literary luminaries from Charles Dickens to Hans Christian Anderson. It is currently occupied by several businesses.

Lennox Tower near Currie is very badly ruined, a mere shadow of its former self.

The huge medieval Craigmillar Castle is where the plot was hatched to murder Lord Darnley, the husband of Mary, Queen of Scots. A true labyrinth of a castle – very much worth a visit – a skeleton was found walled up in the dungeon here.

LOST CASTLES

No matter how many castles currently populate Edinburgh, even more have vanished.

Red Hall Tower in Slateford was destroyed by Oliver Cromwell’s army in 1650, and replaced by the more comfortable mansion of Redhall House a little over a century later.

The only reminder of Curriehill Castle is the road named after it, Curriehill Castle Drive.

Malleny Castle in Balerno had already vanished by the late eighteenth century.

Vague traces of an unknown fourteenth-century stronghold have been found at Broomhall Terrace in South Gyle.

Inchgarvie Castle was a sixteenth-century tower on the island of Inchgarvie in the Forth. Its few remains were incorporated into the gun battery built on the island during the Napoleonic Wars, and then again into the anti-aircraft battery of the Second World War.

Fifteenth-century Mortonhall Castle near the present Mortonhall had a moat and drawbridge, but not a stone or ridge survives of the site.

The ruinous but impressive Granton Castle (aka Royston House) on West Shore Road was demolished after the First World War down to the foundations and beyond.

The presence of the medieval castle of Corstorphine is marked only by its doocot (pigeon house) off Dovecot Road. The doocot is in good condition: the occupants of its 1,060 nest boxes provided valuable meat and fertilizer.

The castellated Georgian mansion of Dreghorn Castle near the bypass was demolished as late as 1955.

Leith has had several fortifications, although you would hardly know it today. The earliest, the vast earthen ramparts erected in 1560 when the Catholic French in the port were besieged by the Scottish and English Protestants, have vanished, although two of the gun platforms built by the besiegers can still be seen on Leith Links.

The fragments of Leith Citadel, built by Oliver Cromwell in the 1650s, can be glimpsed at the northern end of Leith Walk.

In 1779 the Scot-turned-American privateer John Paul Jones sailed into the Firth of Forth intent on attacking British shipping and ports in support of the American War of Independence. He was pushed out to sea by a gale. A small part of the wall and guardhouses still survives of the hurriedly-constructed Leith Fort from this time.

Perhaps Edinburgh’s most comprehensively vanished castle is Dingwall Castle, built in the 1520s on the site of what is now Waverley Station. After a brief life as a courtyard castle and then re-use as a prison, it was robbed for building materials in the 1640s and had disappeared long before the New Town development and the arrival of the railways. Most histories of the city never mention it.

PLACE-NAME PECULIARITIES

Holy Corner, the crossroads of Morningside Road, Chamberlain Road and Colinton Road, is so named because four churches dominate the site.

Irish Corner, meanwhile, was the name given to the junction between Saughton Street and Corstorphine High Street, because of the immigrants who lived there.

The Lawnmarket on the Royal Mile had nothing to do with gardens. The name means Landmarket, that is, the place where the landward, or country people, held a market.

The Grassmarket was once the Sheep Flechts, reflecting its function as a livestock market.

A quaint legend supposedly explains the name of Morocco Land on Canongate. Andrew Grey fled a sentence of death in Edinburgh and ended up in North Africa. After twelve years in exile, and now immensely wealthy, he returned, bent on revenge. However, in a change of plan, he ended up marrying the Provost’s daughter (after first curing her of the plague). Having taken a vow never to set foot in Edinburgh, he settled in Canongate – which was technically outside the city boundaries – and set up a statue of the emperor of Morocco on his house. You can choose to believe as much of this tale as you wish.

Dean Bridge, designed by Thomas Telford, opened in 1832 to link the New Town with the routes to the west. It soon became known as the Bridge of Sighs – because so many people committed suicide by jumping into the Water of Leith 108ft below. The parapet was eventually raised in an attempt to inhibit the jumpers.

By the 1980s the twenty-storey Thomas Fraser Court off North Junction Street in Leith was suffering the social decline common to many tower blocks. As part of the regeneration of the block, it was refurbished and given a suitably upbeat new name – Persevere Court.

The curved structure of Cable Wynd House in Leith meant, inevitably, it was nicknamed Banana Block.

The local pronunciation of Admiralty Street in Leith is ‘Admirality Street’, with an extra ‘i’. Antigua and Montague Streets were pronounced ‘Antaygi’ and ‘Montaygi’ respectively.

A native of Newhaven is known as a Bow Tow.

Wester Hailes Road was originally known as Thieves Road.

The steps leading from Saxe Coburg Street to Glenogle Road were called, with striking insensitivity, the Dummy Steps, because the Deaf and Dumb School was nearby.

The standard explanation for the name of the suburb of Liberton is that it is a corruption of ‘lipper’s town’ or Leper Town, there having supposedly been a leprosy hospital here. However, no trace of such a refuge has been found, and the name Liberton predates the appearance of leprosy in Scotland.

Probably the most disputed placename is Arthur’s Seat. Some people are convinced it refers to King Arthur. Others think it commemorates an entirely different Prince Arthur from the Dark Ages. An idea popular in the nineteenth century was that the name was a corruption of ‘Archers Seat’, on the assumption that bowmen had been based on the commanding height during some medieval battle. The most likely provenance is that ‘Arthur’s Seat’ is a mangled version of a Gaelic placename.

SOME UNUSUAL STREET NAMES

Now-demolished Plainstone’s Close at 222 Canongate was once known as both Bloody Mary’s Close and Bonnie Mary’s Close.

Ewerland in Braehead comes from ‘ewer’, the old word for a basin or jug. The owners of the land, it is said, had been granted the property after saving the life of the king. The only rent they had to pay was to supply the monarch with a ewer of water whenever he rode by. The king’s saviour was supposedly named Jock Howieson, and the site of his alleged cottage is nearby by old Cramond Brig, but the story cannot be authenticated, and is very probably fanciful.

Buckstone Loan and its associated streets north of Fairmilehead are named for the Buckstone or Buckstane, where, according to a charter from the early seventeenth century, the laird of Penicuik was required to thrice blow a horn each time the king unleashed his buckhounds to hunt on the Boroughmuir. In a bizarre addition to this feudal holdover, the laird’s wife was also duty bound to blow the horn, but only once. Having been moved about a hundred yards, the 3ft-high Buckstane now stands next to a wall opposite the Morton Hall Golf Clubhouse.

Edinburgh has ten Colonies. These are not overseas possessions, but streets of ‘model’ working-class housing built to a higher standard than was usual in Victorian cities. The Colonies are found in Abbeyhill, Dalry, Fountainbridge, Leith Links, Lochend Road, North Fort Street in Leith, Pilrig, Shandon, Slateford and Stockbridge. Of these the last named are by far the best known, and the attractive ‘B’-listed two-storey dwellings are now well beyond most working-class pockets.

Coffin Lane suitably runs to Dalry Cemetery. The Gallolee or Gallows-lea, one of the various sites of execution, could once be found halfway between Edinburgh and Leith. It is not clear what the connection is with The Gallolee on the opposite side of the city in Dreghorn.

Lapicide Place in Newhaven refers not to rabbit-killing but the process of stonecutting.

Fishwives’ Causeway in Portobello is another functional streetname, referring to the route taken by the women of the fisher community to the railway station.

Stockbridge is apparently so called because it was where a wooden or ‘stock’ bridge crossed the Water of Leith.

An Old Testament concentration can be found in Morningside, with Canaan Lane, Jordan Lane, Eden Lane, Nile Grove and Egypt Mews. Joppa Grove in Portobello refers to a place on the coast of the Holy Land.

Beulah in Musselburgh is another Biblical name, meaning the land of Israel, although in English literature, as in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, it has come to signify a place of mystical peace, a ‘Shangri-La’.

Pape’s Cottages overlooking the Water of Leith are nothing to do with the Papacy; they were built as accommodation for poor widows, as specified in the will of George Pape.

The lane known as John Knox Way was so named on a request from the Orange Lodge in 1971.

Christian Crescent is not a religious appellation: it was named for a Major Christian, Provost of Portobello.

When much of the uncultivated land on the edge of the city was dangerous marsh, a beacon light used to be lit at night on the east gable end of Corstorphine Church, so that travellers could find their way safely. The lamp was funded from the income of an acre of land; and so we have Lampacre Road. The niche continues to have a lamp, installed by the local Rotary Club in 1958.

A slightly less believable story is attached to St Katherine’s Gardens. Katherine or Catherine was one of the great martyrs of the early Church, whose story is entirely legendary. Oil that streamed from her uncorrupted body on Mount Sinai supposedly had healing powers; and a few drops of this oil was, according to the story, brought back to Edinburgh and deposited in a well here. The well water was a balm for various diseases, and so we have Balmwell Avenue.

Romance and passion are well served with Tryst Park, Lovers Lane and Wanton Walls.

East Lilypot in Granton seems to have been derived from a now-vanished old house called Lilyput or Lilliput, a reference to Gulliver’s Travels.

Picardy Place was named after refugee silk workers, who arrived from the Picardy area of northern France in 1730.

Cockmylane in the south of the city, like so many streets that suggest an intriguing story hidden in the name, is probably merely a corruption of a Gaelic original, in this case cuach na leanaidh