Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

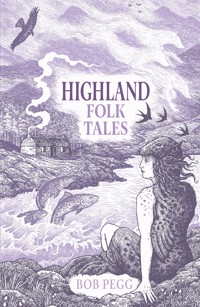

The Highlands of Scotland are rich in traditional stories. Even today, in the modern world of the internet and supermarkets, old legends dating as far back as the times of the Gaels, Picts and Vikings are still told at night around the fireside. They are tales of the daoine sìth – the fairy people – and their homes in the green hills; of great and gory battles; of encounters with the last wolves in Britain; of solitary ghosts; and of supernatural creatures like the selkie, the mermaid, and the Fuath, Scotland's own Bigfoot. In a vivid journey through the Highland landscape, from the towns and villages to the remotest places, by mountains, cliffs, peatland and glen, storyteller and folklorist Bob Pegg takes the reader along old and new roads to places where legend and landscape are inseparably linked.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2012

This edition published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, gl50 3qb

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Bob Pegg 2012, 2025

The right of Bob Pegg to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75247 817 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Wood and Water

The Flying Princess

The Glenmore Giants

Margaret and the Three Gifts

A Great Glen Gallimaufry

The Golden Bowl

Angie and the Calf

Big Sandy of the Goblin

The Three Red Hats

The Blue-Eyed One

Bogles, Big Fellows and a Blacksmith

The Boy and the Blacksmith

A Highland Origin Myth

The Bodach Stabhais

The Gille Dubh of Loch an Draing

The Stalker

Big Hughie Kilpatrick

Travels and Travails

Roddy Glutan

The Tiger-Striped Dog

The Lady of Ardvreck

Waifs and Strays

The Story of Fergus Smith

The Three Advices

The Wee Boy and the Minister

The Wren

Hogmanay at Hallowe’en

Stories in Stone

The King of the Cats

Finn MacCool and the Fingalians of Knock Farril

Miller’s World of Wonders

Thomas Hogg and the Man-Horse

The Postie and the Ghost

The Story of Sandy Wood

John Reid and the Mermaid

Saints and Sorcery

The Desert Fathers

Stine Bheag

The Wild East

The Lady of Balconie

Last Wolves

The Harbour Witch

Frakkok’s Tale

Hidden Kingdoms, Magic Lands

The Seal Killer

How the Sea Became Salt

The Death of Ossian

The Lord of the Black Art

The Highwayman

Afterword

Guide to Gaelic Pronunciation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My old friend and long-time collaborator John Hodkinson has, as ever, surpassed expectation with his bold illustrations.

The stories of Alec Williamson and Essie Stewart – both members of the Highland Traveller community – help form the backbone of Highland Folk Tales, and permission to use them was generously given. Since the book’s first publication Alec has passed away, in 2019 at the age of 87. He was a great, ebullient tradition bearer, in both Gaelic and English. His stories live on.

Dolly MacDonald, who was born in 1918, passed away in 2017. Dolly’s kindness and generosity in sharing her stories – not to mention her forthrightness – were inspirational.

Jenny Neesham first acquainted me with the story of The Flying Princess in 1981, and later gave me a copy of David Thomson’s The People of the Sea, which I had very much in mind when working on this book.

The late Hugh MacNally’s telling of Angie and the Calf and Angus Grant’s recollections of Jimmy the Dolphin originally appeared on the recording ’From Sea to Sea’, released by The Highland Council in 2001.

The Boy and the Blacksmith is © of The Estate of Duncan Williamson, and is used by kind permission of Linda Williamson.

Isabella Ross kindly gave permission to use the family story of The Bodach Stabhais.

Flora Fullarton Pegg reminded me of The Story of Fergus Smith, which I once told, but had entirely forgotten.

Martin and Frieda Gostwick gave invaluable help with the chapter Miller’s World of Wonders and put me right on the fine details of Hugh Miller’s life.

I’m grateful to Isabel Henderson for first making me aware of the story of The Desert Fathers, and inviting me to tell it in Nigg Church, where images from the story are carved into a Pictish cross-slab.

George Adams of Helmsdale passed on information about fishermen’s superstitions.

The receipt of a Creative Scotland storytelling bursary in 2010, for the project Walking the Stories, helped enormously in my exploration of the links between story and landscape in the Highlands.

Finally, my thanks to Mairi MacArthur, not only for her help with Gaelic spelling and pronunciation, but for her unstinting support throughout the writing of Highland Folk Tales.

INTRODUCTION

In 1989 I moved from North Yorkshire to the Scottish Highlands. I came to live in Hilton, one of the Seaboard villages on the Nigg peninsula in Easter Ross. The three communities that make up the villages – Shandwick, Balintore and Hilton itself – thread round a bay in an unbroken string of white dwellings. They are old settlements. Their names, present and past, derive both from Gaelic and from Old Norse. In Gaelic, Balintore is Baile an Todhair, the bleaching town. For the Vikings, Shandwick was a sandy bay, and Cadboll, in the region of Hilton, was the farm of the cats. Out in the bay south of Shandwick is a rock shelf known as the King’s Sons, where local tradition holds that three Viking princes drowned when they came seeking revenge against the Earl of Ross for his cruel treatment of their sister.

The Nigg peninsula is known particularly for the three great sculpted slabs that once stood in Hilton, Shandwick and Nigg (the Hilton stone is now in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, and was replaced by a replica, carved by Barry Grove, in 2000). At one time people believed that the stones had been erected to commemorate the three Viking princes who perished out in the bay. We now know that they were carved by the Picts, some time around the ninth century. They show hunting scenes, bestiaries, trumpeters, a harp, a woman apparently riding side-saddle, together with elaborately ornamented crosses and an array of symbols whose meanings have never been convincingly interpreted. In 1996 the discovery of the site of a Pictish monastery at Portmahomack, at the north-east tip of the peninsula, made it plain why such impressive Christian cross-slabs would be found close by.

One evening early in my first January in Hilton I saw fire, miles away on the far side of the Moray Firth. It was years later that I realised I must have glimpsed the Burghead Clavie, a rare survivor of what, not so long ago, were widespread midwinter fire parades. In Burghead, a blazing tar barrel is carried around the village – the site of a Pictish fort – on the shoulders of local men. Some believe that the Clavie is a survival from pagan times, a vital ceremony designed to ensure the return of light in the middle of winter darkness; it’s a fitting, if romantic, belief, in a place whose latitude is further north than that of Moscow, and whose winters can be long and hard.

The Seaboard villages can seem more isolated than the apparently more remote communities of the West Highlands, even though they are only a few miles off the A9, the main road to the north. Twenty years ago, the majority of the inhabitants were people whose families had lived there at least since the nineteenth century, the times of the Highland Clearances, when they had been evicted from their crofts in Sutherland, and Gaelic was still the first language of a handful of the older folk. They were the last generation of native speakers in the East Highlands, apart from some members of the Traveller community who still speak it today; though even among the Travellers it has almost died out.

One of the native Gaelic speakers in the village when I first arrived was Cathy Ross (there were many Rosses in the Seaboard). She was a tiny little lady who had never married, and who lived in a small, immaculately kept cottage just along Shore Street. Every day she would pass by my front door, taking a walk round the block for exercise, and would always stop to chat. The older inhabitants of Hilton knew her as ‘Toy’.

Dolly MacDonald, another Hilton dweller, was of a generation younger than Toy. I would often see her walking Mac, her West Highland Terrier, along the path between my garden and the beach. One morning I was sitting out in the sun playing the melodeon – an old-fashioned squeeze box. Dolly came towards me along the path, with Mac trotting beside her. She stopped by the gate and danced a little jig to the music. ‘My grandmother used to have one of those,’ she said, meaning the melodeon. ‘There was a lot of music around when we were bairns.’ She began to talk about the old times, and told me the story of a young man who lived in Balintore. ‘Did you hear of him?’ she said.

This is how I remember Dolly’s story. The young man was walking along Shandwick beach one day when he saw in the distance a merrymaid – that was Dolly’s name for a mermaid – sitting on a rock. She was very beautiful and he thought she looked as if she’d make a good wife, but he wondered how he could stop her going back to the sea. He remembered something he’d heard – that if you find a merrymaid sitting on a rock and you walk around the rock three times widdershins, her tail will fall away. He thought he’d give it a try. He walked round the rock three times, and indeed her tail did drop off, and she had a good pair of legs underneath it.

The young man grabbed the tail and ran back to his cottage. He went to the shed at the bottom of the garden, folded the tail up and hid it behind the plant pots. Then he went into the kitchen and waited. Well, eventually he saw the merrymaid coming up the road, getting used to her land legs. She knocked at his door. When he answered it she asked for her tail back. He wouldn’t give it to her, but he did invite her in. They shared a pot of tea and got on quite well together and soon they were married, and in time they had three children.

She was a good mother but she missed her life in the sea. One day the man woke up and there was no sign of the merrymaid. He went down the garden to the shed and looked behind the plant pots, and the tail had gone. Of course she must have found it and slipped it back on and returned to the sea. That was the last the man and the three children ever saw of her.

That was Dolly’s story. I had heard something like it before, told not about a mermaid but a selkie girl. The selkies, whom we’ll meet again later, are shape-changers. They are seals who can become human on land by taking off their skins. The story was about a young man who stole a selkie’s skin, so that she was forced to marry him; it became so popular in the late twentieth century that it was made into a children’s picture book, and became a feminist parable, in which a woman has to choose between her family and her true nature. But tellings of it were always set in a misty Celtic past. Dolly’s story took place just down the road in Balintore, some time within the past few years. The young man himself might still be living, perhaps remarried to a Seaboard girl.

The Highlands are no Arcadia. They famously have a turbulent, often cruel past, and are beset today by the same kinds of social problems and personal fears that afflict other parts of Britain. But hearing Dolly MacDonald tell the story of the merrymaid so casually that summer morning made me realise that I had come to live in a place where old folk tales were still living and breathing, and were part of the landscape and the life of communities.

On one occasion, I had an experience so strange that it felt as if I was actually in one of these stories. Among the many snippets of local lore that Dolly passed on was that there was a family in the Seaboard who were ‘off the seals’, meaning that, like the renowned MacCodrums of South Uist, their lineage had been enriched by a liaison between humans and the people of the sea.

November 5th was a big date in the Seaboard calendar. Small fires were lit in gardens and in streets throughout the villages, but there were two big bonfires, one in Balintore, the other in Hilton, and there was great rivalry between the supporters of each. The house of one of my close neighbours, a retired naval man, overlooked the field where the Hilton bonfire was stacked high, and he had taken it upon himself to keep watch, to make sure the Balintore boys didn’t sneak in and set it alight before the allotted time. When the evening of the 5th arrived, the Hilton field reeled in a bacchanal of explosions and merriment, with schoolchildren, matrons, respectable village tradespeople and shrieking teenage girls weaving round each other, and men brandishing half bottles staggering through the smoke. My neighbour was also the official lighter of fireworks. When the last Roman Candle had expired, and the bonfire was down to glowing ash, he beckoned me into his back garden. The old seadog had managed to procure a bottle of Pusser’s rum, which he had hidden in the garden – but had apparently hidden so well that we couldn’t find it at all (later we discovered that his wife had been there before us, had found the bottle and confiscated it).

‘Never mind,’ he said, ‘I know where there’ll be a drink.’ I followed him back into the field, over stone walls and down little paths for what seemed like miles, until we climbed over a fence into someone’s back garden. Without knocking, the sober sailor entered, with me close behind. In the kitchen, round a big wooden table, sat a group of people who all had round, pale faces and big brown eyes. I felt as if I was the seal killer entering the kingdom of the selkie folk – his story is told later. Surely these were the people Dolly had spoken of. Whether or not they were off the seals, we were shown great hospitality and they were warm company, though I never did meet any of them again.

Seven years after I came to the Highlands, early in the summer of 1996, Mairi MacArthur and I were in Thin’s bookshop in Inverness, for the launch of Timothy Neat’s book The Summer Walkers. The book gathers together the spoken autobiographies of some of the Scottish Travelling people, together with wonderful photographs of the Travellers and their campsites. Two of the book’s subjects were at the launch: Alec Williamson, who had settled in Edderton, where his family used to winter when they were still on the road; and Essie Stewart who, at that time, was living in Inverness, but in earlier days had travelled Sutherland and Caithness with her adoptive mother Mary, and her grandfather, the renowned Gaelic storyteller Ailidh Dall, Blind Sandy Stewart. Tim talked about the book, and then Alec was invited to sing a song in Gaelic. The big voice, from the big man, filled Thin’s, and the ghosts of campfires began to glow among the well-ordered shelves.

You will meet Alec and Essie again, and find out more about their remarkable lives and the tales they heard when they were young. Their stories are still being told today, in the festivals and community events which have sprung from a recent international revival of interest in storytelling. In this collection, I have tried to reflect the spirit of that revival. I have heard, or have told, all the stories here. Most are given in my own words, but if readers would like to explore other versions – and there are many – some references are given in the Afterword.

Many of the stories are very old, and have travelled widely, taking root in different cultures and adjusting to the languages of those cultures with ease. This adaptability has led to their settling down comfortably in particular places, often embracing topographical features and their names, and sometimes incorporating the names of families and individuals from these places. I’ve reflected this attachment to location by arranging most of the stories along the routes of journeys, which can either be taken in the imagination, or through the physical landscape of the Highlands.

The stories are at their best told out loud. This is an invitation to take your favourites, to make them yours and pass them on in your own words, just as storytellers have done for thousands of years.

Bob Pegg

WOOD AND WATER

The Drumochter Pass, which rises a little over 1,500ft above sea level, is officially where the Highlands begin. In the middle of winter it’s more barrier than gateway. The worst of the snows will close the pass, forcing drivers heading north up the A9 to make a massive detour round the east coast, by Dundee and Aberdeen. Even on the finest summer day there is a sense of leaving the modern world behind – the galleries and theatres of Edinburgh, the cosmopolitan eating places of Glasgow – and entering another country, where human affairs are dwarfed by the capaciousness of the landscape, and giants would be the most appropriate inhabitants.

A fantasy … of course. This is a place where human dramas have been played out on an operatic scale; where the destruction of the feudal clan system, following the Battle of Culloden in 1746, was rapidly succeeded by the infamous Highland Clearances that forced great shifts in the population, and added the motive of necessity to an already established enthusiasm for emigration. The Highlands today have modern industry and technology, a cultural life which is particularly rich in music and visual art and a population in which earlier influxes of Celts and Scandinavians have been joined by swathes of more recent immigrants, especially folk from the north of England who find the mountains and lochs and the wilder coastal places particularly congenial.

Yet, perhaps because it was considered a savage region until quite recent times and so stayed relatively isolated, or perhaps because the Gaelic language and its associated traditions still have a foothold, the Highlands, more than any other region of Britain, are rich with stories. The Scots word ‘hoaching’ would describe it better. Every peak and glen, every river, loch and pool, every track, forest and township, has an associated story. And these are tales not just written down in books, but known by communities and passed down through families: stories of fairies, ghosts, giants, waterhorses, witches, the second sight, feuds, betrayals, amorous deeds, and encounters with Old Nick himself.

A detour from the A9 at Newtonmore, along the B91512 and turning east for Coylumbridge just south of Aviemore, leads to Rothiemurchus, where some of the old Scots pines still stand. This is where our first story takes place.

—THE FLYING PRINCESS —

Around 6,000 years ago, when the last remnants of ice from the last Ice Age had vanished from the most northerly parts of the Highlands, life, never completely absent, began to burgeon. Woodlands of juniper and birch started to spring up. Animals came: bear, wolf, beaver, reindeer, aurochs and more; and, of course, humans. Swathes of pine and oak established themselves further south, playing their part in the creation of the semi-mythical wildwood that became known as Caledon.

It wasn’t long before people began to cut down the trees to make clearings where they could erect their dwellings; then to clear land to farm, and use the timber to fuel smelting and to build ships. Climate change, too, played a major part in deforestation, and by the eighteenth century little was left of the old wildwood. Stories began to be told about how and why the trees had disappeared. This is one of the oldest of those stories.

A long time ago, the King of Lochlann (which is the old name for the country we now call Norway), paid a state visit to Scotland. The King of Lochlann and the King of Scotland didn’t get on. One reason was that the King of Lochlann was jealous of the Scottish forests, which were far finer than his own. He decided to act. He sent his daughter to the Isle of Skye, to learn the Black Arts. She was away for seven years, and when she returned home, she brought a little black book with her.

The Princess took the book and climbed to the highest room in the tallest tower of the castle. She locked the door behind her, opened the book, and began to read. As she read, a small cloud started to form outside the window of the highest room in the tallest tower; and as she continued to read, the cloud grew bigger.

When the Princess had finished her incantation, she closed the book and climbed up onto the window ledge. She leaned forward and slipped into the cloud, and the cloud, with a rumble, began to drift down towards the sea. As she flew through the air, the Princess sang a little song:

Over the mountains, over the valleys

Over the burns where salmon are leaping

Down to the sea where sailors are calling

Now my work has just begun

Across the sea flew the Princess, towards the north-east tip of Scotland – the place which today is called Caithness. When the cloud reached the coast, a bolt of lightning shot out of it, and struck the tops of the trees. Soon the great forest of birch and juniper was ablaze. The wall of fire advanced slowly southward, while behind it drifted the Princess in her cloud, singing softly. Ahead of the wall of fire ran the animals – wolves, bears, beavers, wild boar – and the people, the refugees, carrying what little they had managed to grab, before their homes were eaten by the flames. Up in her cloud, the Princess sang:

Over the mountains, over the valleys

Angel of death and fiery destruction

People and creatures fleeing before me

Now my work is almost done

When the first refugees reached Rothiemurchus, they told the people there what was happening. The folk of Rothiemurchus decided to go to the wise man for advice. They had a fine forest of pine trees and they didn’t want to lose it.

‘What shall we do?’ they asked the wise man.

‘The first thing, bring me all your silver,’ he said.

They were poor people, and didn’t have much, but they gathered together some coins, a couple of rings, a brooch and a bracelet, and took them to the wise man. He melted them down and made a silver arrowhead. He bound the arrowhead to a shaft made of rowan wood.

‘What now?’ asked the people. In the distance they could see the wall of flame, and the fire-breathing cloud getting closer and closer.

‘Take all the mother animals. Take the sows and the mares, and the cows and the ewes, and herd them onto that hillside.’

They did this. ‘What next?’ they said.

‘Take all the baby animals. Take the piglets and the foals, and the calves and the lambs, and put them on the hillside opposite.’

The people did this. The mothers saw the babies and the babies saw their mothers, far away on the opposite sides of the glen.

They let out such terrible, heartbreaking cries for each other, that the Princess popped her head out of the cloud to see what was making the racket.

The wise man drew back his bowstring and loosed the silver-tipped arrow. It flew through the air, and went straight into the Princess’s heart. Out of the cloud she fell, and hit the ground, dead as a stone. The cloud became a mist and the mist evaporated. The wall of flame shrank to ashes.

And that’s why, today, a little piece of the ancient Scottish pine forest is left in Rothiemurchus.

And that’s also why, if you know the right place to go, you can still hear children in school playgrounds chanting this clapping rhyme:

A Princess came from over the sea

She came flying with a one, two, three

She flew ’til she came to the Caithness shore

She came flying with a two, three, four

She burnt all the trees and everything alive

She came flying with a three, four, five

She turned all the trees into little black sticks

She came flying with a four, five, six

All the animals cried to heaven

She came flying with a five, six, seven

They cried out early, they cried out late

She came flying with a six, seven, eight

Hear the silver arrow whine

She came flying with a seven, eight, nine

She’ll never try her tricks again

Down she came with an eight, nine – TEN!

—THE GLENMORE GIANTS —

The road east from Rothiemurchus heads into the heart of the Cairngorm Mountains. At its end there’s now a mountain railway that will take you to a restaurant near the top of Cairn Gorm – the Blue Mountain – itself. There are still stories told in this haven for skiers of the Big Grey Man, a presence who is seen, or sometimes just sensed, on the high places. But he’s by no means the only giant in the Cairngorms. At the foot of the mountain is Glenmore, an easy and charming walk bordered by slopes of Scots pine to Lochan Uaine, the Green Lochan.

There are giants in the lands around Glenmore. Best known, perhaps, is Dòmhnull Mòr, Big Donald, the King of the Fairies. Lochan Uaine is green because Donald and his followers wash their clothes there, and fairies’ clothes are green.

One evening, a certain Robin Òg Stewart of Kincardine was on his way home up the glen, when he heard the sound of pipes in the distance. He hid in the bushes and watched as Big Donald’s fairy band approached. The pipes sounded so beautiful, and were so wonderfully decorated with silver trimmings, that Robin wanted a set for himself. So he stood up and shouted, ‘Mine to you, yours to mine.’ Then he threw his bonnet into the middle of the players, and grabbed some pipes.

The band carried on down the track, as if they hadn’t noticed. Robin was well pleased with himself. He hid the pipes under his plaid and went on his way. But when he got back home, all he found in his hand was a puffball, with a twig sticking out of it.

The same Robin Òg was hunting in Glenmore one day, when he managed to bring down a magnificent hind. He started to gralloch the beast and for a moment put down his sgian dubh on the grass. When he looked for it, the knife had vanished; so he took out his dirk and carried on with the job. A minute later he put down the dirk, and it too vanished. Robin took the hind on his back and headed out of Glenmore as fast as he was able.

A while later he was on the shore of Loch Morlich, when he met an old man dressed in grey. The old man pointed at Robin, and Robin saw that his hand was dripping with blood.

‘Now, Robin. You’re here too often, killing my children. Remember that hind you slaughtered not so long ago? You can have your knives back, but don’t let me see you in these parts again.’

Robin took the two knives from the old man, determined to change his hunting grounds. He realised that he was face to face with the Bodach Làmh Dheirg – the Old Man of the Bloody Hand. The Bodach was the guardian of the forest creatures. He more usually took the form of a gigantic warrior who challenged intruders in his domain to mortal combat. The brave, who immediately accepted, were spared, but the timorous met a dreadful end. Robin realised he’d had a very lucky escape.

—MARGARET AND THE THREE GIFTS —

Primarily it’s the Victorians whom we have to thank for our notion that fairies are diminutive, winged creatures. In the Highlands, and in the Celtic countries in general, they are a quite different kind of being. A common belief is that the fairies – or the daoine sìth, the Good People – were fallen angels. When they were cast out of heaven, some fell in the sea, some on the land, and the rest took to the air. Those who fell on the land set up home in grassy mounds which are called sìtheanan, and the Highlands are full of these habitations. The daoine sìth lived, and still live, very close to us humans, and at certain times of the year the doors in the side of their homes are open, and we can peer inside – even enter. We should be cautious though, because tasting their food or drinking their wine – they are extremely hospitable folk – can put us in their thrall, and a happy evening in the Sìthean may turn out to have lasted many decades when we re-emerge into the human world.

The daoine sìth can be good neighbours, and can dally, even intermarry, with humans. But they can also steal from us, and they love to take away our babies.

Glenmore is the perfect setting for the story of Margaret, a young woman who was born with three gifts: a light hand for the baking; a light foot for the dancing; and a light heart to see her through the day.

Margaret lived in a cottage in a clearing in the Glen, with her husband Donald, and their little baby Angus; and if you asked Margaret which of the two – Donald or Angus – she loved the best, she would find it impossible to decide.

Donald was a drover, sometimes away for weeks at the markets in the south. One beautiful day in late summer, during one of his absences, Margaret decided to go on a picnic. She took a bottle of milk and some sandwiches, and set off with the baby up the track to the Green Lochan. In the early afternoon they stopped by a grassy knoll to rest. Margaret had unpacked the sandwiches and taken out the milk, when she noticed a cloud of dust coming up the track towards her. As the cloud got closer, she saw a little old man with a long white beard inside of it. He looked worn and weary, and the dust of the road was on him.

‘Why don’t you stop and share our picnic,’ said Margaret. The little old man sat down beside her. He ate half the sandwiches and drank half the milk. Then he stood up, and spoke for the first time. ‘You’ve been very kind to me. I have neither gold nor silver, but what I’m going to give you is more precious than either.’

He reached into his pocket, and pulled out a rusty old horseshoe nail. ‘Take this,’ he said, ‘and look after it well. It may come in useful sooner than you think.’

Margaret was far too polite to ask what on earth she should be doing with a rusty old horseshoe nail. She thanked him, and slipped the nail into her apron pocket. The little old man set off back up the track, and soon he was gone from sight.

That evening it turned cold. Margaret placed baby Angus in his cot next to the fire, and put a sprig of rowan on top of his blanket, to keep him safe from evil spirits. As she sat spinning, she heard a terrible commotion out in the yard. She thought a fox must have got in among the chickens. She took the lantern and went out into the night to see what was happening, but there was no sign of any fox, and the chickens were safe in their coop.

Margaret went back into the house. As she closed the door, she heard a sound. Hehehehehe! She looked round the room, but couldn’t see where the sound was coming from. Then she noticed that the sprig of rowan was lying on the floor. Margaret went over to the cot, and looked in. Where baby Angus had lain, there was a skinny, brown, mottled thing, with long, sharp finger nails, pointed ears, big, yellow eyes, a grin that stretched from ear to ear, and a mouth full of sharp teeth. It looked up at her and laughed. Hehehehehe! Straightaway she knew what had happened. The fairies had tricked her into leaving the house. When she was outside, they’d stolen baby Angus and put one of their own in his place. A Changeling!

It took Margaret the whole of the night to decide what to do, and most of the next day to pluck up the courage to do it. When evening came she took the Changeling and wrapped it tightly in a blanket, so it couldn’t scratch her face. Then she set off through the woods to the Sìthean, the fairy hill. It was dark when Margaret reached the Sìthean. She picked up a stone and hammered three times. A door opened in the side of the hill, on to a room filled with light. There, in the middle of the room, stood the Fairy Queen. She was a beautiful woman, but it was a cold beauty. By her side was a fairy servant and, in the servant’s arms, baby Angus.

Margaret stepped inside the Sìthean. She dropped the Changeling on the floor and it scuttled away into a corner. ‘I don’t want that thing,’ she said. ‘I want my baby back.’

‘I wonder what your baby’s worth to you,’ said the Fairy Queen. ‘I hear you have a light hand for the baking. Would you give that in return for your baby?’

Margaret didn’t have to think twice. She nodded. The Fairy Queen reached out and stroked her arm, and her hand became as heavy as lead.

‘Now,’ said Margaret, ‘give me back my baby.’

‘I didn’t say I’d give him back.’ said the Fairy Queen. ‘I was just interested in what he was worth to you. Surely more than a light hand? I hear you have a light foot for the dancing. Would you give that in return for your baby?’

Again Margaret didn’t have to think twice. She nodded. The Fairy Queen reached out and stroked her leg, and her foot became as heavy as lead.

‘Now,’ said Margaret, ‘give me back my baby.’

‘Did I say I’d give him back?’ said the Fairy Queen. ‘He must be worth more to you than a light hand and a light foot. I hear you have a light heart to see you through the day. Would you give that in return for your baby?’

This time Margaret did have to think. Without her light heart, she would always be gloomy, and it would be so hard to bring up a child in a house without joy. But she wanted Angus back so badly, that she nodded. The Fairy Queen reached out and stroked Margaret on the chest, and her heart went as heavy as lead.

‘Now,’ she said for a third time, ‘give me back my baby.’

‘Think,’ said the Fairy Queen. ‘If he comes back with you into the world of mortals, he’ll grow old. Eventually he’ll die. If he stays here in our world he’ll always be young. Surely you’d like to give him immortality?’

Margaret lunged forward and grabbed Angus from the arms of the fairy servant. Then she turned and threw herself out of the mound into the darkness, and began to stumble through the trees. She thought that if she could reach the burn and get to the other side she would be safe, because the fairies can’t cross running water. But she could feel them just behind her, playing with her hair, scratching her back with their long, sharp fingernails, and she knew that they could pounce at any time.

Then she tripped on a root and fell. The baby rolled out of her arms, and there was a chink as the rusty old horseshoe nail slipped out of her apron pocket and hit a stone. Margaret groped around and found the nail. She remembered that, if there’s one thing the fairies hate more than running water, it’s forged metal. She turned around, held up the nail, and made the sign of the cross.

‘Stop!’ said the Fairy Queen. ‘Get back, get back. She has cold steel, she has cold steel!’