9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

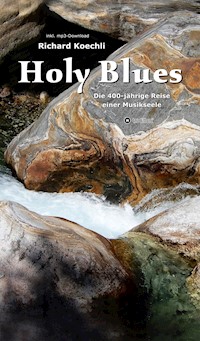

How African American Christian music influenced Western cultural history and forever changed the world of song. What do blues, jazz, soul, R&B, rock'n'roll, folk, country, rock, pop and hip hop have in common? Their origin, their fire! Holy Blues (Gospel Blues) is the source of all the roots music we love. The history of gospel music is 400 years old; its spirit even much older, and without it we simply would not be able to be enchanted by soulful music today. Reason enough to trace this good spirit, Holy Spirit. The award-winning Swiss musician and book author Richard Koechli embarks on an adventurous journey through American cultural history and shows with countless concrete examples how high the influence of faith on the music and its producers has been throughout the centuries, how decisive and mysterious the divine dimension shapes the music at every moment. Koechli does this in a double package: as a book author with a soul stirring history trip, and as a blues artist with very personal interpretations of timeless Holy Blues songs (free download).

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 204

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Imprint

© 2022 Richard Koechli www.richardkoechli.ch/en

German original edition (2021) written by: Richard Koechli

English translation: Richard Koechli

Book cover photo: Heinz Schürmann

Cover-Layout: Richard Koechli, Evelyne Rosier

Editing, proofreading: Donald Meyer, Gerd Bingemann

Printed and distributed by order of the author:

tredition GmbH, Halenreie 40-44, 22359 Hamburg, Germany

ISBN Softcover: 978-3-347-62750-5

ISBN Hardcover: 978-3-347-62751-2

ISBN E-Book: 978-3-347-62752-9

ISBN Large Print Book: 978-3-347-62753-6

This work, including its parts, is protected by copyright. The author is responsible for the contents. Any exploitation is prohibited without his consent. Publication and distribution are carried out on behalf of the author, who can be contacted at: tredition GmbH, Department „Imprint Service“, Halenreie 40-44, 22359 Hamburg (Germany)

Many thanks to: To all those great Holy Blues artists who enriched our music history through their lives, their faith and their work. To all who helped bring their music to the public, the media and the history books. And to all who generously helped to make this project a reality: Evelyne Rosier, Marlise and Walter Koechli, Hape Schuwey, Heinz Schürmann, Andy and Priska Krauer, Sylvia Frey, Bruno Amstad, Urs and Françoise Friderich, Thomas Bühlmann, Relaxing Blues Music (Deb, Eric and the whole team), John in Houston PR, Reinhold Weber, Gerd and Ursi Bingemann, Marianne Frischknecht, Prof. Dr. Jacob Thiessen, Seyde Barsimon, the Tredition-, CMS-, Fontastix- & cede-Team. To my longtime live band (Fausto Medici, David Zopfi, Michael Dolmetsch, Heini Heitz, Dani Lauk) and my loyal, fine audience. And of course to God, His Son Jesus Christ, the Blessed Mother Mary and all good spirits for succor, strength, inspiration and encouragement in all times.

Contents

Holy Blues - Richard Koechli, the audio album

Holy Blues (Prologue)

The 400-year history of Holy Blues

Slave Songs, Work Songs

Call and Response, Polyphony

William Wells Brown (1814 – 1884)

Spirituals

Isaac Watts (1674 – 1748), the musical revolution in words only

African America begins to emancipate itself

Spirituals as a political instrument

Harriet Tubman (1820 – 1913)

Go Down Moses

Down by the Riverside

Deep River

Wade in the Water

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

Follow the Drinking Gourd

Steal Away

The American Civil War

Spirituals on stage

Fisk Jubilee Singers

Songs of survival

Gospel

The first recordings of black music

George W. Johnsons (1846 – 1914)

Unique Quartette

Dinwiddie Colored Quartet

Minstrel Shows

Blacks flee to the north

The Barbershop Quartets

The Pentecostal Movement

Azusa Street Revival

Holy Blues is marketed

Homer Rodeheaver (1880 – 1955)

Jack L. Cooper (1888 – 1970)

Race Records

Street preachers and evangelists, the music revolution of the 20th century

Arizona Dranes (1889 – 1963)

Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915 – 1973)

Robert Johnson (1911 – 1938)

Blind Joel Taggart (1892 – 1961)

Reverend J.M. Gates (1884 – 1945)

Blind Willie Johnson (1897 – 1945)

Mahalia Jackson (1911 – 1972)

Thomas A. Dorsey (1899 – 1993)

Sallie Martin (1895 – 1988)

Holy Keyboard, the Hammond B3 organ

The breakthrough, the gospel quartets

Black Gospel Quartets

Golden Gate Quartet

Dixie Hummingbirds

The Soul Stirrers

Samuel ’Sam’ Cooke (1931 – 1964)

The Fairfield Four

McCrary Sisters

Blind Boys of Alabama

Mountain Gospel

Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys

Southern Gospel

Charles Davis Tillman (1861 – 1943)

(Poor) Wayfaring Stranger

James D. Vaughan (1864 – 1941)

Stamps Quartet (Give The World A Smile)

Blackwood Brothers

Statesmen Quartet

Allan ’Charlie’ Rich (1932 – 1995)

Closing words

Mississippi John Hurt (1892 – 1966)

Blessed Be The Name (of the Lord)

B.B. King (1925 – 2015)

Ry Cooder

Kelly Joe Phelps

Richard Broadnax (1948 – 2020)

Underrated – underestimated stars

Arizona Dranes (1889 – 1963)

Vera Hall (1902 – 1964)

Reverend Gary Davis (1896 – 1972)

Doc Watson (1923 – 2012)

More from Richard Koechli

Richard Koechli

Holy Blues

Prologue

Whether the blues is holy or, as is often claimed, the devil, is something I pondered with a mixture of irony and seriousness back in 2014, in my book Dem Blues auf den Fersen(On the Heels of the Blues). Fred Loosli, the protagonist of that story, searched in vain for an answer to the question of why there has always been a distinction between blues and gospel. Fred never really understood the difference. Understandable - there is no difference.

The inseparable connection between gospel and blues is ignored as much as possible in the music business. The blues has to be dirty, bad boys and bad girls sell better. On the commercial surface, every genre needs its label, I can understand that. But in depth and from a music-historical point of view, such clichés don't last long. Just T-Bone Walker's famous statement "the blues is just gospel turned inside out" makes everything clear - the two seemingly opposite poles are the essence of our music. Without gospel, the blues would not exist.

In our enlightened world, this sounds strange: Music is inseparable from the divine. It sounds like a metaphor at first, of course. When the German music journalist, producer and jazz musician Joachim-Ernst Berendt spoke of Nada Brahma, the world is sound, he meant it metaphysically, philosophically. Berendt understood music as an expression of human existence in itself, comprehensible in the context of the social and also religious context.

But even on the physical, scientific level, the world is sound. "For us, the world-space is a place of silence, but space has its own sound track," says American physicist Janna Levin of Barnard College in New York. "It's a composition made up of dramatic events. The big bang is everywhere. Space billows and vibrates. The song of the Big Bang is still ringing around us." Sounds kind of like science fiction, but has long been dry, grounded knowledge. "Everyone can hear this spectacular primeval sound", emphasizes Hannes Sprado in his book Der Klang des Weltalls (The Sound of the Universe), "because in analog television reception, 1 percent of the noise consists of the afterglow of the Big Bang: At any time of day or year, electromagnetic rays with a wavelength in the millimeter and centimeter range strike the Earth's surface from all directions. Radio waves reach us from the darkest corners and the most remote areas, bringing news from a distant time, from nowhere, so to speak. They tell of the past, they describe the present, and they proclaim the future."

Kind of fits with the creation story in the Bible where God said, "Let there be…" A good friend of mine, the blind musician Gerd Bingemann, is convinced: "To these spoken instructions even nothingness had to react and bring forth the things brought about by God's word."

What is summoned is then not merely metaphysical or philosophical; Joachim-Ernst Berendt also gets very specific when he writes in his multi-part series Vom Hören der Welt (On Hearing the World) - the ear is the way a very interesting example is interspersed: The light waves of the sun, the moon and various planets were measured and then octavated down into the frequency range audible to the human ear - the results were fascinating: The earth vibrates after this octavation relatively sluggishly rattling in a tone close to G; "that is, neither in a tonal carpet of sound that cannot be clearly grasped nor as a diffuse noise," Gerd Bingemann adds.

Well, pondering about it can be very inspiring. In this book, however, I would like to focus more narrowly. I am not so much interested in the Big Bang, but rather in the music of our culture: blues, jazz, soul, country, folk, pop, rock. On the one hand as a performing musician as well as someone interested in music history - in the hope of being able to feel and produce songs and sounds even more intensely. On the other hand, as a Christian, in order to understand (according to Berendt) the music in the context of the social and religious context.

Religious context? Doesn't sound very cool to modern ears, as I now. Of all things, the music that embodies the soundtrack of our liberated individuality, the music that began to loosen the shackles of religious constraints in the 1950s and 1960s, that cleared up superstition and false morals - that is supposed to be of divine origin? For the current zeitgeist, such statements are pure provocation. Whereas he, the zeitgeist, is fully betting on the religion-bashing card, stubbornly assuring us that the world would be a thousand times better and more peaceful without religion, that our ancestors are supposed to have been superstitious idiots, and that we are finally entitled to the right to self-realization without a corset. Now, of all times, when this zeitgeist seems to be getting right, the churches are almost empty, the old hocus-pocus stuff is gradually disappearing from our everyday life - now, of all times, Koechli comes along and claims that our music of today would simply not exist without God, faith and religion? Even more audacious: That Jesus not only shaped our western history in general, but that we also owe him, at least indirectly, our beloved Anglo-American roots music?

It seems pretty crazy to me myself, this realization. Sure, I always had in the back of my mind that spirituals and gospel songs exist. It's not that I was never interested in them; even on my very first CD Trains of Thought from 1992 I played an instrumental version of Go Down Moses and Amazing Grace, because such songs seemed somehow sacred to me and made an impression. But in the end, I found them to be a detail of music history, nothing more. As time went on, I dove deeper, I became something of a blues musician, as you know - but I still had the impression during all those years that gospel was at best a pious and therefore not quite as cool sister of the blues. Yes, and now, in the course of researching this book here, I realized that gospel is not the sister, but the mother. And Jesus Christ therefore actually the father, the forefather!

Of course, Jesus is not the only crack; there are other cracks from the spiritual world to blame for our music. The Islamic prophet Mohammed, for example, also had a hand in the Blues, from the very beginning. So did some of the African gods like Papa Legba from the Voodoo religion. Prophet Moses, of course, the founder of Judaism, was there in spirit when Jewish artists and businessmen helped the African-American musical soul make its commercial breakthrough and successful turn on to the pop music highway in the 20th century. And let's not forget the Eastern religions, Hinduism, Buddhism; they played a decisive role in the blues revival, the birth of rock music and the hippie movement in satisfying the enormous hunger for spiritual kicks.

So, peace, joy and happiness in the big spiritual family of the music world? Not quite, no. Let's not kid ourselves - of course a few dark figures were trying to interfere all the time, as they always do. The jamming anecdotes are well known: The famous Crossroads rendezvous of the old bluesmen with the devil, for example, or the occult shenanigans of certain rock stars, who, drug-addled, at times fell defenselessly for the mischievous tricks of Aleister Crowley, Anton LaVey and their ilk. But in the end the jammers, as clever as they tried, could not cause any lasting damage - the blue notes remained in the care of good powers and consecrate themselves to this day in the positive sphere of influence of the world religions. "Holy Blues", yeah.

It has saved countless lives, these holy blues. And now, as a gift, he's even given me a kick that no LSD trip in the world could - the kick, that is, to write this book. Hallelujah!

You notice, dear readers, I occasionally pack a hint of irony into my narrative. But, I want to make a serious and inspiring contribution to the reappraisal of the history of the blues and its spiritual background. I'm glad you're joining me on this historic journey. I'm not the type of tour guide who has walked the path countless times, knows every stone and blade of grass, and recites the travelogue. I am just as much on a voyage of discovery myself, feeling my way along, being surprised again and again by new discoveries.

That the Blues also has Islamic roots was not clear to me for a long time. The decisive, style-forming inspiration for this music came, as is well known, from the Christian-influenced spiritual and gospel music, but the Africans who were taken to the new world of the colonial powers in the course of the transatlantic slave trade were influenced spiritually in various ways. Africa's religious history is diverse. And right from the start: religion is not a side issue in Africa - it encompasses almost all areas of life and plays a central role for most people. Africans do not like half measures. For them, spirituality is not just wellness or mind games; they often live their faith with uncompromising intensity and devotion, and they know from their ancestors that the relationship to the invisible world is not humbug, but the most natural thing in the world.

Christianity and Islam today share the religious majority in Africa; Islam tends to be more in the north and west, Christianity more in the centre and south. The third largest group is a collection of traditional ethnic religions, and in addition there are of course numerous syncretic religions, i.e. mixtures of ethnic religions with Christian or Islamic ones. Judaism, by the way, also played a role in Africa for thousands of years; Jewish communities lived scattered over the African continent from very early on, the "Falasha", for example, whose ancestors were Israelites who emigrated to Ethiopia in the 10th century BC.

The African slaves thus had different backgrounds when they were abducted to their new homeland. Some were of Christian origin (the first historical evidence of a Christian presence in Africa dates back to the 4th century), others were of Muslim origin (shortly after the death of the prophet Mohammed in 632, Islam had begun to spread in Africa), and still others had a mixture of religious baggage. In the course of the centuries that were decisive for the history of the Blues, many Afro-Americans converted to Christianity - and yet, in addition to the already formative African musical traditions, there is most likely also an Islamic component in the Blues: the call to prayer.

Was the Field Holler (call-song during fieldwork) an Islamic call to prayer …? According to historical records, an Ethiopian named Bilal was the first muezzin (caller); in 622 or 623 he is said to have called Muslim believers to prayer for the first time. Not yet from a minaret (minarets were not erected until after the Prophet's death), but from the roof of a house in Medina, in western Saudi Arabia, the second most important holy city in Islam after Mecca. Piquant detail: Bilal was a black African slave, a freed slave, previously tortured by his Arab master, finally freed by Abu Bakr al-Sadiq, a wealthy Muslim benefactor. Out of gratitude and joy, Bilal converted to Islam, climbed to the roof of a small mosque, and with longdrawn-out shouts called the people to prayer. The "Adhan" was born - the art of the melodious call to prayer. Today, it is sung in the Islamic world in countless regional nuances, in various "maqams" (modes, keys), rooted in Arabic tradition, with the typical three-quarter-tone intervals of Arabic music.

Bilal's call to prayer from Medina was exported to America about a thousand years later with West African slaves, and finally gave rise to the legendary Field Holler - and thus the blues. At least that is what the New York social historian Sylviane Diouf and the Austrian ethnomusicologist Gerhard Kubik are convinced of. For Diouf, "the proximity of the Holler to the Muslim call to prayer is very striking", and Kubik describes the musical style found in the Holler and in the blues of the Mississippi Delta as "Arabic-Islamic".

Most likely, there is a kernel of truth in this theme. The only problem is that we don't know the original Holler of the slaves. The oldest Holler recordings date from the mid-1930s, some Blues recordings from the 1920s (such as Mistreatin' Mama by Jaybird Coleman) show strong connections to the Field Holler tradition - but then at the latest the acoustic thread breaks off. We do not know how these calls sounded in the 17th, 18th or 19th century. The Field Holler of the 20th century was influenced by Blues recordings of that time, both were already mixed at that time. Sylviane Diouf refers to the legendary Levee Camp Holler of W.D. 'Bama' Stewart (recorded by Alan Lomax in 1947, in a Mississippi labor prison). This Holler does indeed bear a certain resemblance to the Muslim call to prayer, and it is very possible that Bama's origins were Islamic. However, to draw a direct and unambiguous line from the Blues to Islam seems a bit daring to me.

And yet justified. About 30 percent of the Africans deported to America were Muslims; the majority of the slaves came from West and Central Africa, i.e. from areas that were partly influenced by Islam. Sylviane Diouf is convinced that Muslims in slavery maintained the Islamic religious practice as far as possible, continued to recite the Koran and called to prayer. Historically, this is not certain, but it is quite obvious. Most Afro-Americans became Christians later (during the development of the gospel and blues) - nevertheless, some of them also had spiritual heritage from the Muslim culture.

Traditional African heritage anyway; the music of Africa, itself influenced by various cultures, has a rich, millennia-old tradition. The call to prayer may indeed have migrated to the Field Holler, but the Holler is by no means the only root of the blues. Spirituals and collective work songs, for example, differ markedly in vocal style from the Holler. The African-American holler was described by 19th-century witnesses as a lonely and melancholy call that lifts, ebbs, and tips into falsetto. Hollers were sung alone, without rhythm, as opposed to collective work songs. Emotional singing was a tradition in Africa anyway; shouting (an expressive shouting style of singing) during work, or moaning (lamenting) at funeral ceremonies - both ancient African rites, and in both one senses a proximity to the later Field Holler. I would therefore say: the Muslim call to prayer is with some probability a blues gene, yes, but by no means the only one.

The entire history of African music contributed to the blues. In Senegal or Mali, for example, music, combined with dance and storytelling, has been the most important form of artistic expression since time immemorial. Traditionally, there is a regular caste of musicians there, the so-called griots, comparable to troubadours, bards from Celtic culture or the unionized music profession today. Also in the highlands of Ethiopia such professional storytellers were on the road, there they were called Azman. The pattern was always about the same - Storytelling accompanied by percussion and stringed instruments. The most important instruments were the ngoni, xalam, riti and kora (in Mali and Senegal), which resemble a lute, and the one-stringed box spit lute masinko (in Ethiopia). The closeness to the later slide guitar is conspicuous in the case of African single-stringed instruments; stepless pitch shifting, that is.

But it is not only the link to bottleneck playing that stands out. The traditional kora and ngoni music with its repetitive riff character is fundamentally reminiscent of the archaic Mississippi delta blues. In Lutz Gregor's documentary Mali Blues, one hears the well-known desert blues musician Bassekou Kouyaté from Mali say, "everyone knows that the blues originally comes from here". Although this sounds like an exaggeration, it is certainly a part of the truth. If anyone is competent, it's Kouyaté; he was born in Garana (Mali) into one of Africa's most important griot clans and masterfully carried the musical heritage into our musical culture through celebrated performances together with stars like Ali Farka Touré or Taj Mahal.

The music from Senegal or Mali is older than the influence of Islam and Christianity. When the transatlantic slave trade began in the 16th century, these areas were still largely anchored in older African religions. Islamization of Senegal began between the 9th and 11th centuries in the north of the country, spread among the Wolof aristocracy between the 13th and 16th centuries, but continued to be the religion of a minority and reached its present influence only in the 18th and 19th centuries, as an anti-colonial movement, so to speak. In Mali, on the other hand, a strong Islamic influence started already in the 11th century, but for a long time it was limited to the wealthy elite (ruling families, merchants and wise men) of the urban centers. The majority of the population in Mali remained faithful to traditional African belief systems; the formation of Islamic states did not occur until the 19th century.

Let's be under no illusion - we will never be able to determine the exact lines of origin of blues and jazz. So it's a case for experts to argue. What is clear, however, is that the roots lead to Africa, and that the genres only really emerged in North America. Above all, however, it is clear that without religion in general (during the time before slavery) and without Christianity in particular (during the style-forming phase of spirituals and gospels in the USA), there would simply have been no blues, no jazz and thus no pop and rock music.

To want to let this fact be forgotten will probably be the great kick of the zeitgeist. Everything would be better without religion? Bullshit, pardon. In any case, the zeitgeist gets a slap in the face if you remind it of another ancient branch in the family tree of the Blues: the Indians. At least since Catherine Bainbridge's excellent documentary Rumble - The Indians Who Rocked the World we know how strong the influence of indigenous musicians (Link Wray, Jesse Ed Davis, Jimi Hendrix and many more) was on the development of rock music - and how the influence started much earlier, through indigenous Delta and Chicago blues pioneers like Charley Patton or Tampa Red. So Indian spirit also had a hand in the blues, and how religious the Indians were is not something we need to discuss anyway. With their belief in the one great spirit, in animate nature, in the power of visions, dreams and guardian spirits - Indians are something like spiritual paragons. Not at all meant mockingly, but with a lot of respect and admiration.

So then let me prove with pleasure that the blues, its essence and all its stylistic children would not even exist without this spiritual background. Ultimately, therefore, not just a "without religion everything would be worse", but downright a "without religion there would simply be nothing at all". I'm sorry, dear zeitgeist, it's over, you're done …

Don't worry; I know he won't admit defeat so quickly - and will probably try it right away with a surefire club: "Koechli wants to sell the Christians, of all people, as good blues spirits? What a nonsense! Christians, ha, the biggest of all scoundrels, who, greedy for power, got us into this whole barbaric slavery, this criminal colonization at all!"

Not a bad chess player, this zeitgeist. It's difficult to respond to that. Unless you expose his move as a clumsy reduction of world history, as a cliché. The widespread idea that the Western world, the "old white men" of our Christian culture, invented colonization, oppression and enslavement - is in fact a fundamental error. Slavery, to the shame of our species, is as old as humanity; it has existed in every civilization and on every continent. So too in Africa, and long before the transatlantic slave trade began. "Slavery was part of different African cultures," explains Abdulaziz Lodhi, professor emeritus of Swahili and African linguistics at the University of Uppsala in Sweden, in an interview with DEUTSCHE WELLE radio on August 22, 2019. In the same interview, African anthropologist and economist Tidiane N'Diaye emphasizes that "in central East Africa, ethnic groups such as the Yao, Makua and Marava fought each other, whole peoples inside the continent traded with people they had captured through wars" - and had done so since time immemorial, that is, "before settlers came from outside." When these settlers, Arab Muslims, finally arrived in the 7th century, "they encountered intra-African structures that facilitated the purchase of slaves for their purposes."