8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

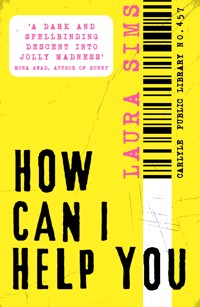

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

** 'A MARVELLOUSLY INTENSE, READ-IN-ONE-SITTING GAME OF CAT AND MOUSE AMONG THE BOOK STACKS' - GUARDIAN **

From the author of Looker comes this razor-sharp suspense about two librarians whose lives become dangerously intertwined.

No one knows Margo's real name. Her colleagues and patrons at a small-town public library only know her middle-aged normalcy, congeniality and charm. They have no reason to suspect that she is, in fact, a former nurse with a trail of countless premature deaths in her wake. She has turned a new page, so to speak, and the library is her sanctuary, a place to quell old urges.

That is, at least, until Patricia, a recent graduate and failed novelist, joins the library staff. Patricia quickly notices Margo's subtly sinister edge and watches her carefully. When a patron's death in the library bathroom offers a hint of Margo's mysterious past, Patricia can't resist digging deeper - even as this new fixation becomes all-consuming.

Taut and compelling, How Can I Help You explores the dark side of human nature and the dangerous pull of artistic obsession.

PRAISE FOR HOW CAN I HELP YOU

‘A dark and spellbinding descent into jolly madness’ – MONA AWAD

‘A gripping and dark psychological thriller... Delicious... I read it one sitting’ – HARLAN COBEN

‘A sly meditation on art and identity and the depths we'll go to protect our constructs. I couldn't have loved this book more’ – PAUL TREMBLAY

‘With transfixing dual female narrators and an artful, innovative structure, How Can I Help You is both a riveting commentary on false pretenses and an utterly beguiling cat and mouse thriller’ – KIMBERLY McCREIGHT

'Openly indebted to Shirley Jackson and Patricia Highsmith, this is a terrific two-hander... This makes for fine cat-and-mouse (or cat-and-cat?) suspense, but also an unsettling moral tale' - SUNDAY TIMES

'A fun and entertaining cat-and-mouse novel... a perfect book for when you just want to sit back, relax, and read about women behaving badly... you'll fly through the pages' - GLAMOUR

‘A delicious mystery begging to be enjoyed beachside… Sure to satisfy just about any thriller craving’ – ROLLING STONE

‘Unnerving... reads like a homage to Shirley Jackson’s work’ – NEW YORK TIMES

‘Sims plumbs the depths of obsession and madness... deftly building the tension until the explosive ending’ – WASHINGTON POST

‘Fresh and funny... A quick read that is reminiscent of Laura Lippman's Sunburn and Christine Mangan's Tangerine’ – BOOKLIST

** A Publishers Weekly Book of the Week **

** A CrimeReads Book of the Month **

** A Town & Country Must-Read Book of the Summer **

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Praise for How Can I Help You

‘Unnerving… reads like an homage to Shirley Jackson’s work – and, in its portrait of Patricia, to Jackson herself. Sims’ great achievement is to present the two main characters almost as sides of the same coin, colluding in a psychological cat-and-mouse game that only one can win’ – New York Times Book Review

‘Sims plumbs the depths of obsession and madness as she has each woman tell the story in alternating chapters, deftly building the tension until the explosive ending’ – Washington Post

‘Bringing workplace politics to a fever pitch, How Can I Help You is a delicious mystery begging to be enjoyed beachside… Equal parts cozy mystery and nail-biter, Laura Sims’ latest novel is sure to satisfy just about any thriller craving’ – Rolling Stone

‘A fun and entertaining cat-and-mouse novel… You’ll fly through the pages as Margo and Patricia play mind games, try to outsmart each other, and ultimately both get what’s coming to them’ – Glamour

‘A book lover’s dream… A taut, high-stakes thriller set in a library… that culminates in a shocking climax’ – Parade

‘A Highsmithian cat-and-mouse thriller featuring two librarians… Sims’ work harkens back to the complex personality studies of mid-century psychological fiction, and pays homage to middle-aged womanhood – serial killers age too, after all’ – CrimeReads

‘Ingenious… How Can I Help You is smartly scary entertainment that will have readers guessing about its outcome until almost the final page’ – Shelf Awareness

‘A psychological thriller that stands out in a crowded field… Give this unputdownable title to readers who revel in messy and complicated characters’ – Library Journal (starred review)

‘A brilliant slice of psychological suspense… Sims skillfully alternates between the perspectives of each woman, slowly bringing her simmering plot to a boil, and delivers a stunning climax. Patricia Highsmith fans will savor this unforgettable thriller’ – Publishers Weekly (starred review)

‘Intense from page one, you’ll root for, abhor, and see yourself in these women as the story makes its way to a disturbing climax. It’s gently creepy’ – Scary Mommy

‘A gripping and dark psychological thriller about two librarians that takes place in a library. Delicious, right? What more do we book lovers need to know? I read it in one sitting’ – Harlan Coben, The TODAY Show

‘A dark and spellbinding descent into jolly madness, How Can I Help You is reminiscent of Shirley Jackson at her eerie best. All of Sims’ deliciously wicked powers are on full display in this compulsive and unforgettable novel. A classic’ – Mona Awad, author of Bunny

‘With transfixing dual female narrators and an artful, innovative structure, How Can I Help You is both a riveting commentary on false pretenses and an utterly beguiling cat-and-mouse thriller’ – Kimberly McCreight, author of A Good Marriage

‘An insidiously readable psychological trap… Skillfully constructed and observed, Laura Sims’ novel is a sly meditation on art and identity and the depths we’ll go to protect our constructs. I couldn’t have loved this book more’ – Paul Tremblay, author of A Head Full of Ghosts

‘No one writes about obsession like Laura Sims. I may never look at libraries the same again’ – Samantha Downing, author of A Twisted Love Story

‘Sims’ sharp, incisive second novel is an out-and-out page turner’ – Marcy Dermansky, author of Very Nice

‘A roller coaster ride of psychological suspense… A sensitive story about artistic ambition, the need to be seen and heard, and the fragility of relationships formed both inside and outside the workplace. You’ll never look at your colleagues, or your local community librarian, in the same way again’ – Helen Wan, author of The Partner Track

For Mona and her profanely inspiring advice

‘In the library, time is dammed up – not just stopped but saved. The library is a gathering pool of narratives and of the people who come to find them. It is where we can glimpse immortality; in the library, we can live forever’

– Susan Orlean, The Library Book

‘Who has not asked himself at some time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?’

– Clarice Lispector, The Hour of the Star

‘It is madness to write things down’

– Elizabeth Bowen, The Death of the Heart

I. Working Like the Devil

MARGO

The moment I walked through the front door, I knew. That deep, abiding quiet, and the sense that the outside world couldn’t reach me here. I was like someone chased by demons across the threshold of a church, stepping into the library that first time. I could have turned around, right there at the door, and stuck my tongue out at the world.

Can’t catch me.

I didn’t do it, and besides, the world wasn’t watching. Couldn’t find me anyway, could it? I’d already changed my hair and makeup, my clothes, my voice, and even the way I walked. I’d changed my name, too. I’d been Jane but I was Margo now. I liked Margo. Jane would have turned and stuck her tongue out, but Margo never would. No, Margo simply stood in the vestibule, shoulders back and head held high like a queen.

I hadn’t spent much time in libraries before then. It was quiet as a nighttime ICU ward – maybe quieter, without all the noise that goes with slow dying: the whoosh of respirators, the mechanical beeps of infusion pumps. I stared up at the high, vaulted ceiling and around at the egg-white walls, then sat down at one of the public computers. I checked the want ads and saw one for circulation clerk right there at the Carlyle Public Library. I toiled over a cover letter and résumé for an hour or so, then handed them in at the desk. ‘I was so happy to see this job come up,’ I said to the stout, red-haired woman there. She seemed managerial, but I learned later that Liz was just a regular staff member. ‘I can’t imagine a more peaceful work environment,’ I went on, waving my arm around. She chuckled a bit, as if I’d said something funny. But from what I could tell, the library was just that: quiet, anonymous, orderly, and sane. From the grandness of the old building to the way the light slanted through the high windows that afternoon, I knew I’d landed in a cozy, carpeted, outdated vault, and I loved it on sight. The job was what I wanted, too: helping people. Not the way I’d helped them before, at the hospital, but still. I would be serving others. When I’d glanced around at the careworn souls sitting at the monitors that day, I’d known there would be plenty of work for me here, plenty of helping to do.

Liz and I struck up a conversation. I told her how long I’d been in town, how much I was enjoying the weekend farmers’ market – though I hadn’t even been – and the birdsong outside my window every morning. She seemed like the bird-watching type. I told her I’d seen cardinals, wrens, and woodpeckers, though the only birds I’d really seen were the pigeons in the parking lot of my Soviet-era apartment complex, pecking at the ground. I told her a tale about moving from Indianapolis, where all I could hear was the roaring river of cars. I told her I’d hated it, hated the overrated canal walk and the seedy downtown, and had moved for a much-needed change. Liz and I were laughing like old friends before long, and she said she’d put in a good word for me.

And now here I am, two years later, checking out patrons’ books, DVDs, and audiobooks, answering their questions about overdue fees with patient grace, policing the computers where I myself sat that first day, making sure the guy in the baseball hat who comes in on Fridays doesn’t watch porn while he’s pretending to job-search. I understand now why Liz chuckled that first day; the library is peaceful, on the whole, but disturbances happen. Patrons shout into their cell phones, throw tantrums over lost books, or hide, half-naked, in hidden corners of the stacks. I’m never bored here – the way I thought I might be when I first arrived.

I sneak up behind Friday Guy, as we’ve come to call him, and lean right over his shoulder so my breath is hot on his neck. ‘Hey,’ I say. He jumps and fumbles, tries to click screens to cover up the giant tits I just saw bouncing before my eyes. Then he looks up, red-faced. Sweating, even in the cold of the main room. ‘You know the rules,’ I say, drawing up to my full height. ‘Yes, ma’am.’ I feel a deep tickle when he calls me ma’am and obeys me like a scolded dog. ‘I’m watching you,’ I tell him. ‘Yes, ma’am.’ He blinks up at me with his sad gray eyes. After a long pause, I walk away.

Liz and the younger clerk, Nasrin, watch me return to the desk, triumphant. ‘You’re amazing,’ Nasrin says, shaking her head in wonder. I just shrug. ‘You should have seen the double-Ds he was ogling today,’ I say, lifting my eyebrows. Nasrin covers her mouth as we all stand there, the two of them giggling like children. I don’t even bother being discreet – I’m laughing my deep laugh when Friday Guy slinks past the desk, still red-faced, carrying plastic bags full of loose papers as usual. Every time I think: He won’t come back. He’ll find some other unsuspecting branch, one without a Margo. But every Friday, he’s there, eyeing those tits, waiting for me to catch him. I guess he likes the game of it.

I like the game of it, too. My nipples, tucked inside my padded bra, get hard every time we perform our little ritual. It isn’t like my hospital days, but it’s better than nothing.

I had to earn this swagger, though. I didn’t start out swishing through the aisles, expertly managing Friday Guy and others. When I first started, I was clueless, fumbling, and forgetful. I made rushed notes on a legal pad, things like:

• DO NOT renew patrons’ computer time more than once, for more than an hour

• Password for scanner is: SCANTHIS

• Checkout forms for hotspots and tablets in drawer to my right

• Must take elderly/infirm patients patrons downstairs in elevator with smallest key on ring

• Call the non-emergency police number for someone acting out but not dangerous

• Call 911 for someone dangerous to himself or others

The last two items tickled me, but I’d held my face still as Yvonne, our director, explained what could differentiate one situation from another: realistic threats of violence, a weapon suggested or in sight, crazed appearance or language. She used the male pronoun for every scenario she described, so I wrote it down: he, he. And she was right, for the most part; the only times I’ve punched the numbers 911 into the phone, it’s been for men. Men can never keep their violence to themselves.

But incidents like those were and are rare, though even ordinary scenarios flustered me back then. When someone approached the desk without books in hand, it meant they had a question, one I wasn’t sure I could answer. I tried to draw on my nursing expertise, but a nurse isn’t much good in a library. And I wasn’t supposed to be a nurse, of course; I was supposed to be an ‘experienced library assistant,’ like my résumé said. So I bluffed my way through as best as I could, and if Liz, Nasrin, or Yvonne caught me in a slip, I’d just say that my last library had different systems for everything. They accepted my ignorance – welcomed it, even. They were endlessly forgiving and kind. Quick to swoop in and rescue me from disgruntled patrons, though most of the patrons were patient with me, too, telling me I had a beautiful smile or an infectious laugh even when I was failing to help them. They used my name when they learned it, and that made me feel seen. Well, ‘seen’ in the safest way possible; they saw me as Margo, or Ms Finch – not as Jane, of course. Some days I felt the way I had in my earliest nursing days – when my uniform was a crisp, bright blue and I’d swell with pride at the slightest praise. For those first few weeks at the library, I let myself be as ignorant and swaddled as an infant; it felt like floating in a nice, hot bath.

I’ve always believed in the restorative properties of baths – for my patients and myself. I’ve bathed many a human body in distress and seen the wonders that steam and hot water can work. Even when the file said ‘sponge bath only’ I would defy it and fully bathe the poor soul. They needed it, didn’t they? And I was strong enough to handle their bodies on my own. It was a bit of a struggle, but we all need to be immersed in water, cleansed and petted by human hands. A sponge bath just doesn’t cut it. Though I would limit myself to sponge baths if I were under close observation, as I often was in the final days at one hospital after another. I would start off cheerful, energetic, everyone’s favorite new colleague. Eventually, though, they’d start to look at me too long. Whisper when I left the room. They would ask me things like, What were you doing in Mr Hammerson’s room? Why have you checked this and that out from the medicine supply? Why haven’t you noted here and there what you’ve done in the file?

They also interfered with my patients’ baths – but they couldn’t interfere with my own. Back at home, I’d close my eyes in the tub and sweat out the rancor and suspicion they piled on me, from one place to the next. Sacred Heart. Green Grove. Union Community. Highland Medical. Spring Hill. Each one started as a paradise – like the names suggest – but ended in quiet fury and disgrace.

My fury; their disgrace, I remind myself.

But Margo tries not to linger in the past. It does her no good. She was wronged; she moved on. Movement is key, I’ve found. To always be moving, wherever I am – even in circles sometimes.

I sweep by the computer aisle whenever I can. Push in the empty chairs with my hip and straighten the stacks of notepaper and tiny pencils arranged near each station. As I make my rounds today, a rumpled old man leans back and calls me over, his sad eyes brimming with almost-death, his need to be held – and possibly bathed – tugging fiercely at my insides.

‘Miss, can you help?’ he asks. When I reach him, I put my face close to his and look at his screen. I smell his sour breath, the unwashed scent of his clothes, and don’t falter for a second. I inhale deeply through my nose so he’ll know I’m not repulsed one bit. Not even one tiny bit. ‘The screen froze,’ he says. I push a button here and there, toggle the mouse back and forth, then sigh. ‘We’ve got to shut this thing down and start it back up,’ I tell him. ‘Sometimes that’s all it takes. Don’t you worry.’ I make the screen go black. Then I punch the power button and bring it back to life. His face lights up like he’s seen the workings of a god. ‘Thank you, miss.’ ‘Of course.’ I hold him with my eyes, probing those pathetic depths, then I let him go.

Do I feel a twinge of frustration?

I do.

Those eyes, begging me for help. I want to help – the way I used to. But I left the last hospital in the dust, and that’s how it should be. No – should be doesn’t matter. That’s how it is. Margo doesn’t live in some imaginary world where Jane goes on doing her rounds. Margo lives in the real world: the library. To prove it, I grab a stack of books to reshelve, tell Nasrin I’ll be back. But when I’ve found my rhythm – locating each book’s spot, sliding it into place – the hospital sneaks back, seeps into me: the peaceful night-shift realm I used to inhabit amid the honeycomb cells of the ICU. I would roam back and forth, back and forth, practically gliding on those smooth, polished floors, checking pulses here and there, resting my warm hand on a sleepy head. Leaning down to feel a faint breath on my cheek, my lips.

But chaos could erupt from the heart of this quiet, too; suddenly I’d find myself standing by a patient’s bedside as commotion descended: hurried footsteps, shouted directions. I stayed calm, soothing the forehead or hands of a struggling one, shushing them gently, steadily handing this or that to the doctor while keeping my eyes locked on the terrified eyes. I’d show them my shining face and my beatific smile and they clung to it, hung their souls onto it, and sometimes they gripped my arms with their wasted claws and literally held me, and I let them. They needed me. I was their living, breathing saint: their nurse. Even if I couldn’t save them. Even if, at that point, no one could.

‘The ones that die are the lucky ones,’ I once said to Donna, the head nurse I considered a friend – a close friend, the closest friend I’d ever had. I said it right after an ‘untimely death,’ one that had rattled everyone – even the patient’s neglectful family. They said she was doing OK two days ago, her eldest son choked out through tears. From what I’d seen and from what the day nurses said, he’d only visited twice, and both times he’d sat in the corner staring blankly at game shows on the hospital TV. He didn’t kiss her brow or talk lovingly to her the way I always did, in the quiet of night. I saw how lost she was, how alone. I saw what she needed in the pools of her eyes when they stared up at me in the muted light.

I hadn’t meant to say what I said to Donna out loud, but I had, and there was no taking it back. A small part of me thought she might agree, but she stared. ‘Really? You really think that, Jane?’ she asked. Like she’d never considered it herself. Like she hadn’t seen how they shuttled so many sad, crippled, hurting souls from the ICU out through the main doors into cruel sunshine and wished them well, sent off to linger alone in some shadowed room until time finished them. They may as well have given them a great shove into the busy parking lot and left them wherever they fell. The untimely-death woman didn’t appear to fit that mold – not to a casual observer like Donna – but I’d witnessed the woman’s suffering firsthand. Maybe she would have gone home and recovered, but to what end? There were crueler fates than a quick death. But Donna didn’t get it, or couldn’t stomach it, or just couldn’t admit the truth of it to herself, so I told her I was kidding and left it at that. She opened her mouth to say something more but then closed it and shifted her eyes away. Usually, Donna and I could chuckle over anything. But that time she pursed her lips and took a sip of tea.

Through the years, I’ve learned to be careful. Careful what you say and to whom, careful how you carry yourself at all times. I carried myself regally on my rounds, and then let my hair down and laughed hysterically in the break room. Always had a tale ready to cheer up my fellow nurses. Made-up stories of my love life, raunchy jokes, lies and more lies. Sometimes they laughed until they cried. ‘Jolly Jane,’ they said, shaking their heads and wiping their eyes. ‘Tell us another one. No – don’t!’

‘Did I tell you about the time my ex-husband lit his own pants on fire?’

‘The old man in 307 waved me over just now, beckoned me close, and then he squeezed my tits like two melons! Dropped right back to sleep after that, like he’d had his snack and was satisfied.’

‘That raving homeless woman who was in the other night kept telling me she could turn her piss into wine! I asked her to bring me a cup.’

I’d have the whole room rapt or in stitches. Nurses needed help, too – they were tired and traumatized by all they’d had to touch, see, smell, and do. They left the break room feeling renewed; I saw to that. I was holding the hospital – whichever one it was at the time – up and afloat in the palm of my hand. And they knew it, every one of them knew it, but it didn’t stop them from chasing me out, pitchforks in hand.

Closing my eyes for a moment, I relish having escaped, having found my way to the library. Late Friday afternoons tend to be quiet, but I can still drift on the tide of familiar sounds: the soft clatter of fingers across keyboards, the thud of books landing in the return slot, the ruffling of pages, the mechanical whoosh as the front door opens and closes, sealing us inside. Standing here, swaying a little, I feel as relaxed as I might after a long vacation. I never felt this way at any hospital; it was a great burden, you know, helping so many for so long. Jane loved it, but it hardened her. Margo is softer, and less hurried, too, in her dealings with patients. Patrons. Patrons. It shouldn’t matter what we call them, really; they’re the same in the end. Patrons will land in hospital beds at one point or other – for sickness, for surgery, for death. I can’t touch them the way I touched patients, though; I might pat someone on the hand or back, or possibly squeeze an arm, but that’s as far as it goes. Sometimes I miss the heft and smell of flesh other than my own, the rigors of my practice as a nurse, but I tell myself how lucky I am, to be a librarian.

Sticklers would say I’m not a librarian – I have no official degree. Liz lords it over me sometimes, though it’s not as if patrons know the difference. To them I’m Ms Finch, the librarian. I even bought reading glasses that hang on a beaded chain around my neck. I love raising them to my eyes to peer down at the book title a patron has written down, or at the monitor of a troublesome computer. ‘Thank you, Ms Finch,’ the patrons always say, with some reverence, when I’m wearing my glasses. Instant gravitas.

When the glasses are off, though, I’m quick to laugh. Sometimes my laugh rings out in the quiet and rattles a patron or two, who look up, as if they would admonish me. But they can’t – libraries now allow laughter. And some level of noise. This took some getting used to at first, when I would circulate and shush the teens in their after-school corner of the adult floor. They chose the spot where outdated technology books met crumbling old biographies, but I sought them out. They would blink up at me as if I were an indiscriminate mass instead of a woman who stood nearly six feet tall, towering over them, staring. They’d pause for just a moment, then resume chatting. Yvonne pulled me aside one day and explained: ‘The library is a community center now. It’s a gathering place. We want people to come together and, yes, talk, if they want to. We want young people to come here and hang out. If they grow up in the library, they’ll value it later, see?’

Sounded desperate to me, grasping. But Margo smiled and nodded.

I’m not interested in the young anyway, so it was easy to leave them be. Throbbing with health as they are, insolent and arrogant in their certainty of immortal life. Give them twenty or thirty more years, let them taste a bit of failure, loss, sickness, uncertainty, and death, and then wheel them into my room; I’ll care for them without an ounce of resentment. They’ll long to hear my rubber soles squeaking down the hall and look for my hand bearing a tiny paper cup of pills or a needle full of merciful relief. They’ll let me turn their bodies on the bed, checking for sores, scanning the bedpan to see what they’ve done, and if they’ve done something, I’ll say, ‘Good girl’ or ‘Good boy,’ and they’ll glow with pride as I tidy them up, put their sheets right, push a stray hair out of their eyes, change the channel for them if their hands are too weak to hold the remote. They’ll thank me then – with trembling chins and bright wet eyes.

I mean they would thank me. They would.

•

One day, during my first year here, Liz asked, out of nowhere, ‘Do you read?’ with that sharpness to her voice that told me it would bother her if I said no. So I told her, ‘Of course,’ and went on pulling books from the shelves, examining their publication dates and the condition they were in. I clenched, waiting for her follow-up questions: Who’s your favorite author? What’s the best book you’ve read lately? But they didn’t come. I was relieved but insulted, too. We went on weeding. I had a small pile of books beside me I thought should be pulled from the collection; Liz’s pile was larger. Was that because she was a reader and had some secret knowledge I wasn’t privy to? I told myself I didn’t care. The truth is I don’t read; when I’ve tried to here and there, it’s been too unsettling, reading someone else’s thoughts and feelings in fine print. I have enough of a time dealing with my own thoughts and feelings – why should I take on someone else’s, too? Also, I’m far too busy – or I was. When I worked as a nurse, I’d go home, eat, and fall into a deep sleep. It isn’t like that now, but I still have no desire to read. Readers aren’t doers, are they? And wherever I’ve been, whether Jane or Margo – or that other one, the first one – I’ve always been a doer.

Even so, I couldn’t stop hearing Liz’s question: Do you read? As if it were a crime to work in a library and not go on and on about books the way she and Nasrin did. I spent my lunch hour that day scanning the fiction shelves, hoping to show up back at the desk with a novel or two in hand. Wouldn’t that have thrown her? I would have been casual about it, would have slid them into my bag like it was something I did all the time. But as I stared at a row of books by authors with last names beginning with V, I couldn’t make heads or tails of any of them. Two Trains Running by Andrew Vachss, Find Me by Laura van den Berg, Call Me Zebra by Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, The Secret of Raven Point by Jennifer Vanderbes, Acceptance by Jeff VanderMeer… the names and titles started to blur. I reached up and plucked Find Me from the shelf at random, flipped through to the first lines: ‘Things I will never forget: my name, my made-up birthday… The dark of the hospital at night. My mother’s face, when she was young.’ I slammed the book shut. I felt like someone had snuck up behind me, tapped my shoulder, and said my original name out loud. I put the book back, enjoying the motion of that: of putting it back, of making sure the spine was lined up with the others beside it. That gave me pleasure, just the way it always gave me pleasure to arrange the medicine on shelves in the hospital supply room. When they’d ask me, ‘What were you doing in there for so long?’ I’d say, ‘I was straightening the shelves – what a mess!’ And I wasn’t lying, exactly – I always left things neater than they’d been before. My questioners would smile, nod their heads, mutter thanks. By the end, though, they’d have a cold look in their eyes when they saw me leaving the supply room.

Things I will never forget: that cold look in their eyes.

At some point, the hospital director would call me into their office and hand me a referral letter. Grimly, as if it pained them to do it. Jane took the letter with pride, like it was something she’d asked for, and went on to the next place, and the next – until Spring Hill, where it ended.

Which brought me here, among the books. I didn’t have to read them to know how to care for them, no matter what Liz said; I certainly didn’t need to read to know how to care for the people who wanted them. While Liz sat there, perusing the books, or the library’s catalog of books, or the internet’s lists of books, I was out on the floor, working like the devil: sanitizing computer workstations, straightening flyers for the next Friends of the Library jewelry sale, and giving patrons whatever help they needed, whatever company they wanted. That, in my view, was being a librarian: being a doer.

‘You never stop,’ Nasrin said once, admiringly.

‘That’s because I can’t,’ I replied, laughing.

And it’s true: Instead of one lap around the public computers, I do three. And if the glass panes on the front door are looking grimy, I grab the 409 and a roll of paper towels. ‘You don’t need to do that,’ Yvonne said once, touching me gently on the arm as I scrubbed. ‘Oh, it’s all right,’ I said, smiling back at her. ‘But our cleaning crew will do that,’ she explained. I already knew. She thought it was beneath me, I guess, to be cleaning the windows. But I’ve also found that it’s better to have a task than to circle like an anxious cat.

Lately I have been anxious. Even with work filling my days, I’ve felt the edge of dread creep in. Is it the sudden onset of fall? The early dark? Is that all that’s bugging you, Margo? I can’t think what else, except that I’ve been here now for over two years, and that’s longer than I stayed at any one of my hospitals. Maybe that’s all that’s making me restless and moody, a little bit bored.

Perhaps. Or maybe it’s something coming down the pipe. Something I can’t see yet, though I sometimes find myself staring into space, toward the front door.