Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Barnes & Noble's April Book Club Pick An Amazon Top 10 Editors' Pick A Most Anticipated Book of 2024 from Literary Hub Set in a not-too-distant America, I Cheerfully Refuse is the tale of a bereaved musician taking to Lake Superior in search of his departed, deeply beloved bookselling wife. Encountering lunatic storms and rising corpses from the warming depths, Rainy finds on land an increasingly desperate and illiterate people, a malignant billionaire ruling class, crumbled infrastructure and a lawless society. Amid the Gulliver-like challenges of life at sea, Rainy is lifted by physical beauty, surprising humour, generous strangers and an unexpected companion in a young girl who comes aboard. As his essentially guileless nature begins to make an inadvertent rebel of him, Rainy's private quest for the love of his life grows into something wider and wilder, sweeping up friends and foes alike in his strengthening wake. A rollicking narrative in the most evocative of settings, I Cheerfully Refuse is a symphony against despair and a rallying cry for the future.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 486

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Leif Enger

Peace Like a River

So Brave, Young, and Handsome Virgil Wander

First published in the United Kingdom in 2025 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

First published in the United States of America in 2024 by Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Reuben Land Corporation, 2024

The moral right of Leif Enger to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 80471 082 1

E-book ISBN 978 1 80471 083 8

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

for Robin

first do no harm

HERE AT THE BEGINNING it must be said the End was on everyone’s mind.

For example look at my friend Labrino who showed up one gusty spring night. It was moonless and cold, wind droning in the eaves, waves on Superior standing up high and ramming into the seawall. Lark and I lived two blocks off the water and you could feel those waves in the floorboards. Labrino had to bang on the door like a lunatic just to get my attention.

Still, it was good he knocked at all. There were times Labrino was so melancholy he couldn’t bring himself to raise his knuckles, and then he might stand motionless on the back step until one of us noticed he was there. It was unnerving enough in the daytime, but once it happened when I couldn’t sleep and was prowling the kitchen for leftovers. Three in the morning—just when you want to see a slumping hairy silhouette right outside your house. When the shock wore off I opened the door and told him not to do that anymore.

But this time he knocked, then came in shaking off his coat and settled murmuring into the breakfast nook. I knew Labrino because he owned a tavern on the edge of town, the Lantern, where the band I was in played most weekends. He was lonely and kind and occasionally rude by accident, but above all things he was a worried man. He said, “Now tell me what you make of this comet business.”

He meant the Tashi Comet, named for the Tibetan astronomer who spotted an anomaly in the deep-space software. From its path so far, Mr. Tashi believed it would sweep past Earth in thirteen months. He predicted dazzling beauty visible for weeks. A sungrazer he called it, in an article headlined The Celestial Event of Our Time.

I admitted to Labrino that I was awfully excited. In fact I’d driven down to the Greenstone Fair and picked up a heavy old set of German binoculars with a tripod mount. Didn’t even haggle but paid the asking price. I wanted to be ready.

Labrino said, “These comets never bring luck to a living soul, that’s all I know.”

“How could you know that? Besides, they don’t have to bring luck. They just have to show up once in a while. Think where these comets have been! I’ve waited my whole life to see one.”

He said, “You know what happened the last time Halley’s went past?”

“Before my day.”

“Oh, I’ve read about this,” said Labrino. Whenever things seemed especially fearsome to him, his great bushy head came forward and his eyes acquired a prophetic glint. “Nineteen eighty-six, a terrible year. Right out of the gate that space shuttle blew up. Challenger. Took off from Florida, big crowd, a huge success for a minute or so—then pow, that rocket turns to a trail of white smoke. Everybody in the world watching on TV.”

I told Labrino I was fairly sure Halley’s Comet was not involved in the Challenger explosion.

He said, “You know what else happened? Russian nuclear meltdown. One day it’s, ‘Look, there’s the comet!’ Next day Chernobyl turns to poison soup. Kills the workers sent to clean it up. Kills everything for a thousand miles. Rivers, wolves, house cats, earthworms to a depth of nineteen inches. Swedish reindeer setting off the Geigers. I wouldn’t be so anxious for this if I were you.”

I couldn’t really blame Labrino. The world was so old and exhausted that many now saw it as a dying great-grand on a surgical table, body decaying from use and neglect, mind fading down to a glow. If Lark were here she would prop him right up and he wouldn’t even know it was happening. But she was late getting home from the shop, and I, like a moron, felt annoyed and impatient, also weirdly protective of a traveling space rock, so I said, “It still wasn’t the comet’s fault.”

“I’m not claiming causation,” said Labrino, his skin pinking. “I’m saying there are signs and wonders. The minute these comets appear in the heavens, all kinds of calamities start chugging away on Earth.”

I opened my mouth, then remembered a few things about my friend. He had a grown son living in a tent on top of a landfill in Seattle. A daughter he’d not heard from in two years. His wife had enough of him long ago, and he was blind in one eye from when he tried to help a man crouched by the road and got beaten unconscious for his trouble. That Labrino was even operative—that he ran a decent tavern and hired live music and employed two bartenders and a cook who made good soup—testified to his grit.

I said, “Is there anything you’d like to hear, Jack?”

He lifted his head. “Yes, that would be nice—I’m sorry, I don’t mean to be such awful company. It’s just the times. The times are so unfriendly. Play me something, would you, Rainy?”

My name is Rainier, after the western mountain, but most people shorten it to the dominant local weather.

I fetched my bass, a five-string Fender Jazz, and my tiny cube of a practice amp. Labrino was calmed by deep tones. They helped him settle. Sometimes he seemed like a man just barely at the surface with nothing to keep him afloat, but I’d learned across many evenings that he was buoyed by simple progressions. Nothing jittery or complicated, which I wasn’t skilled enough to play in any case. My teacher was a venerable redbeard named Diego who explained the ancient principle “first do no harm” from early bassist Hippocrates: lock into the beat, play the root, don’t put the groove at risk. Diego said a clean bass line is barely heard yet gives to each according to their need. If I played well then Labrino saw hillsides, moving water, his wife Eva before she got sick of him. There in the kitchen he relaxed into himself, eyes closed, mouth slightly open, until I feared he might crumple and fall to the floor.

Thankfully Lark arrived before that could happen, gusting into the kitchen like a microburst. Laughing and breathless, her hair shaken loose, she had a paper bag in hand and a secret in her eyes.

“Why, Jack Labrino,” she said. “I thought you had forgotten all about us,” which pleased him and changed the temperature in there. Right away he dropped his apprehensions and started talking like a regular person, even as she went straight through the kitchen and set her things in the other room. Out of Labrino’s sight but not mine, she shed her jacket and sent a sly smile over her shoulder.

I picked up the tempo, increased the volume and landed on a quick straight-eight rhythm, which turned into the beginning of an old pop-chart anthem I knew Labrino liked. He grinned—a wide grin, at which Lark danced back into the kitchen and held out her hand. Labrino took it and got up and followed her lead. She whisked him about, I kept playing, and Labrino kept losing the steps and then finding them again—it was good to see him prance around like a man revived. By the time I brought the tune to a close Labrino was out of breath and scarcely noticed as Lark snagged his coat and lay it over his shoulders. With genuine warmth she thanked him for coming and suggested dinner next week, then he was out the door and turning back to smile as he went.

“Thanks for getting home when you did,” I said in her ear. We’d stepped outside to see him off, his coat whickering in the hard wind.

“You were doing just fine. But you’re welcome all the same.”

Labrino made it to his car, eased himself into it. It seemed to take a long time for the car to start, the lights to come on. Pulling out he waved, then drove slowly down the street.

I felt my lungs relax. I liked Labrino, wanted him to be all right. But I also really wanted him to go home, and be all right at home.

Lark said, “Sometimes your friends choose you.”

She took my hand. Her eyes flared wide then got stealthy, and at the bridge of her nose appeared two upward indents like dashes made by a pencil. It was irresistible, my favorite expression—of all her looks it built the most suspense, and it was just for me.

quixotes

BACK INSIDE Lark picked up the paper bag she’d carried in earlier, holding it close to her chest as though what it contained were embarrassingly lavish. Clearly drawing out the pleasure of reveal she said, “We have a boarder coming tonight. We’ll have to get the room ready.”

We had a third-floor attic that was sometimes for rent. It wasn’t much—a bed in a gable with a half bath. Mostly it lay vacant. Not for lack of travelers—pitted and hazardous as the highway had become, a lot of people were on it. Nearly all were heading north and keeping quiet. So we were careful about our attic. Yet we were also, as Lark liked to whisper in the dark, quixotes, by which she meant not always sensible. Open to the wondrous. Curious in the manner of those lucky so far.

I said, “You seem pleased about this boarder. Somebody we know?”

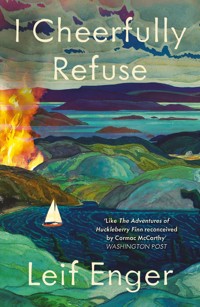

“It’s not who he is. It’s what he brought.” And she reached in the bag and pulled out—slowly, with glittering eyes—a book, or rather a bound galley, an advance copy produced for reviewers. It was beat-up and wavy with ancient humidity, blue cardstock cover flaking badly. Printed in fading black was its title: I Cheerfully Refuse.

“You can’t be serious.”

Lark laughed. It was her habit when delighted to rise lightly on tiptoe as if forgotten by gravity. I Cheerfully Refuse was the personal grail of my bookseller wife, the nearly but never published final offering of the poet, farmer, and some said eremite Molly Thorn, a woman of the middle twentieth. Molly lived many lives. Essayist, throwback deviser of rhyming verse, chronicler of vanished songbirds, author of a single incendiary novel in which the outlaw protagonist speaks in couplets and occasional quatrains. Lark said she was a cult author before they became the only kind.

“He had this galley copy with him,” she said now. “Kellan, I mean, the new boarder. He came in the store with a little stack of titles. What are the chances?”

“How long have you looked for that book?”

“Since I was twelve.” By then Lark had read everything else of Molly Thorn’s thanks to her mother, a profligate reader and purveyor of impertinent ideas.

“Have you already finished it?”

“Haven’t started even.” She was up on her toes again. “Rainy?”

“Yes?”

“You want to read it first?”

I hesitated. I wasn’t sure I wanted to read it at all.

“I know, me too,” she said. “I’m almost afraid to open it.”

We went to the attic and put sheets on the bed and two heavy quilts against the draft. Swept the room though it was neat. While we worked Lark told me Kellan was young and scrawny, with concave limbs and a red rooster comb for hair. She said, “You’re going to notice his hand.”

“His hand.”

She described a mottled claw burnt to ruin. Glossy and immobile, it got your attention.

“This Kellan, is he a squelette?”

The term, French for skeleton, was popularized a decade earlier when a dozen Michigan laborers seemed to vanish. It happened at a factory like many others, manufacturing drone rotors and home-security mines on the west Huron shore—night shift, dirty weather, they stepped out for a smoke and never came back. Ordinary American citizens, filling six-year terms for bread and a bunk under the Employers Are Heroes Act. No one imagined a dozen gaunt ingrates fleeing by water that violent night, bolting an outboard to a patched pontoon and piloting through fifty miles of mountainous waves to the obscurity of Manitoulin, then mainland Ontario where they were discovered by a grandfather with a beret and a crooked walking stick like a wizard’s. Their haunted forms rising out of the grass so startled the old Québécois that he hobbled into the fog shouting, “Squelettes! Squelettes!” Since then thousands of such laborers had made similar desperate breaks.

“I didn’t ask.”

There was a reading lamp up there and we left it on for Kellan. I went downstairs, filled a pitcher with water, and brought it up with a glass to set on a stand beside the bed. Out the gable window the light of a boat shone on the violent sea. Nobody should be out there. Most of the time nobody was. I couldn’t see the boat at all, only its light, which pitched queasily and dimmed and vanished and reappeared among the endless swells.

Kellan arrived soon thereafter. It was early still, about nine. We heard his car making sounds of distress long before it pulled in. Big old square precentury Ford. He opened the back and pulled out a child’s cardboard suitcase of fading plaid and carried it blinking into our kitchen.

Lark was right about the rooster comb and bony limbs. She had not mentioned his protruding eyes or nervous demeanor. She was also right about the claw. I offered to carry his suitcase upstairs, but he held it to his chest as though I might rob him. He was dinky and frail with a sheen on his brow. He moved as if encountering resistance.

“Have you eaten?” Lark said.

“I’m all right.” He was clearly starving but seemed to weigh the meal against the obligation of eating in our company. The road makes introverts. Lark told him: Take these stairs all the way up, they creak like a houseful of spooks but they’re safe, the light’s on in your room.

And up he went, suitcase in hand, dragging his shadow like chains.

I woke in the night. It took me a minute to remember we had a stranger upstairs. A bedspring spoke, a floorboard. The half bath tap went on and off. I heard Kellan paw through his suitcase, then what sounded like the very faintest white noise. Distant static or airflow. This was so quiet and went on so long I stopped hearing it.

“You’re awake,” Lark whispered.

“Sure. Are you?”

The question was sincere. Lark was a lucid sleeptalker and could listen and respond as though fully alert. Sometimes we had whole conversations while she slept.

She said, “I think so.”

We whispered back and forth. There’s a pleasant whirr you get when your favorite person wants to stay awake with you but can’t. It was three in the morning and we both knew she would go to the shop at seven. She loved the shop. She also loved seven. What she had was built-in.

I said, “Did he tell you where he got that book? Or was he too shy?”

“Not shy,” she said. “Enigmatic. Obscure. In subsequent days he’ll win renown, but he won’t really like it.”

I smiled in the dark—Lark had the habit, when very tired, of predicting upshots in the lives of people just met. She never let them hear these yet-to-comes, these subsequents, which were purely for herself and sometimes me.

“But where is he going in the meantime?”

I could see her fading and only asked this to hear her voice again.

“To his uncle’s in Thunder Bay. Oh, Rainy.”

“Yes?”

“Will you help him fix his car? I think he needs a part.”

“Probably more than one.”

I rolled to my side and after a moment felt the warmth of her palm against my back. That’s how she preferred to slip away. I liked it too.

From upstairs came the sound of hollow metal hitting the floor and rolling, coming to rest against the wall. Like a thermos bottle or a bit of plumbing. Then quiet, and we slept.

the Greenstone Fair

LARK WAS GONE when I woke. Clean sunlight shifted on the ceiling, ravens murmured in the eaves. For the first time in weeks I couldn’t hear waves hitting shore.

Like always I stepped outside first to see what the lake was thinking.

It’s called a lake because it is not salt, but this corpus is a fearsome sea and if you live in its reach you should know at all times what it’s up to.

For now a calm day beckoned, the sky washed clean.

You enjoy these days when they come. They are not what the lake is known for. The year after we moved in a cloud gathered on the surface and rose in a column twenty thousand feet high. It was opaque and grainy and stayed there all summer like a pillar of smoke. That season two freighters went down in separate storms—a domestic carrying taconite and a Russian loaded with coal. People blamed the dark cloud because in both cases it shredded before an arriving storm only to reconstitute after, like a sated monster at rest. It was also true that by this time many satellites had been taken out by rival nations or obsolescence, so ships using GPS often found themselves blind in a gale, but the scowling cloud was hard to ignore. A belief took hold that the lake was sentient and easily annoyed.

But not today. I took a quick stroll to the shore where a bit of homebuilt seawall slumped over the water. An otter poked up its round head, flashed sharp teeth, and rolled under. The lake was dark and flat. It was a blackboard to the end of sight, and any story might be written on its surface.

Back at the house I scouted the fridge. Breakfast for the boarder was up to me. We had a dozen fresh eggs—a luxury—also bread, jam, a bag of greenish oranges. I poured beans in the grinder and stood turning the handle. There’s no way to do this quietly. When I glanced up Kellan was standing by the table giving me dubious looks.

My impulse was to laugh. Those startled eyes! He looked like a bagged fowl released into daylight.

He said, “Is Lark here, or just you?”

I told him she’d gone to the shop. He looked like he wanted to go there too. “People your size make me nervous.”

It wasn’t an unusual response. I tapped grounds into a filter and nodded at a chair. Something about Kellan felt familiar, not his face but his frame and bearing. Scrawny-aggressive. Pants held up by knotted twine. I said, “I’m not dangerous, most days.”

He sat, swallowed, still looked anxious. This was never to change. He was terribly narrow front to back, by which I mean he was a ribbon. The neck of his T-shirt was a stretched mouth and his gingery hair grew thickest on the bony ridge of his skull. I had a great-grandmother who gauged the health of her poultry by their spiky red combs and he was robust by this measure. His other bird feature was the claw hand that looked pulled from a forge and rubbed to a waxy shine.

I set about frying eggs. “You’re a welcome arrival,” I said, to put him at ease. “That book you brought, twenty years she’s looked for it.”

He nodded but said nothing, transfixed by the sight of breakfast taking shape before him. Mouth open, eyes narrow, he tilted stoveward. It didn’t seem unlikely his good hand would dart out and seize the spattering pan. Given this rapt audience I tilted up the cast-iron and basted and peppered with all the flair I could manage. I was a little proud of my sunny-side eggs and slid them with slices of fried toast onto a stoneware plate.

Kellan ate like a man falling forward, a pileup of elbows and tendons. Even his wrists were concave. My throat lumped a little, watching him. Most of us knew how it was to be hungry. Frequently we’d been close enough to care, as the song says, though the only person I knew who’d actually starved to death was my great-uncle Norman who did it on purpose, another story. This young man wrapped his claw around the oval plate and leaned down as though it might pop out some legs and zigzag away. I broke more eggs. Eventually he leaned back and rubbed his face and squinted out at the sun.

“Where to from here?” I asked. What was it I recognized about this Kellan? I couldn’t have told you—not yet.

He didn’t answer at first, then murmured “farm” and “Ontario” with gaze averted. I must have seemed nosy and in fact I was. I mentioned the Molly Thorn book again—how hard Lark had looked for it, how happy it made her to have got a copy at last.

“Um,” he replied.

“Where did you find it, if I may ask?”

“Mm.”

His reserve didn’t surprise me, nor the fact he’d been more forthcoming with Lark the previous day. Knots untied themselves at her approach. Then I happened to glance out the kitchen window. Kellan’s massive auto leaned into the grass like the lethargic rhinos of old.

“Haven’t seen wheels like that in a while,” I remarked.

At which Kellan’s head bobbed up. You could see he was proud of his daft huge car.

“Ford Ranchero.”

“What a survivor. Lark says you need repairs.”

And this was the thing that got him talking—not easily, he still looked away from my eyes as though I’d struck him recently, but he did narrate in chirpy bursts how he’d found the antique Ford in a salvage yard only a week ago. It had a new head gasket and did not leak oil, though acceleration left behind inky blue clouds that took a long time to disperse. After two days the front end began to knock. Intermittently at first. Now it banged all the time like something trying to get out. An old man in Wisconsin diagnosed a corrupt ball joint. Maybe more than one. Kellan wondered was there a mechanic in Icebridge.

“Everyone in town’s a mechanic. Your problem is going to be parts.”

“Lark said you might know where to find them.” How easily he said her name, Lark, like he’d trusted her for years.

I told him Greenstone was the place. No guarantees of course but generally you find what you need in Greenstone. If you don’t find it, someone will make it or try to make it. How I love that town. I could tell you stories but not right now.

Kellan fell quiet, asked for more coffee, went to the window and drank it watching the street. He peered back and forth, leaned close to the glass and gazed into the sky. An early spring day with watery sun. I fried one more egg and laid it across a slice of bread, ate it while wiping down the counter. Kellan suggested we take the Ranchero for a drive so I could hear the noises it made.

“I’m no mechanic,” I said.

“You said everyone is.”

“Everyone else.”

The car started after a series of complaints. It was a handsome tumbledown brute. It had rough ocean-colored paint through which smooth continents rose up and peninsulas and islands of hardened putty. Once it had been nicely kept. These old cars remember smoother roads than I do.

We took a short ride to demonstrate the issue. To say the Ranchero knocked is polite. It pummeled. It dragged a nightstick across the bars. Kellan shouted over the racket while I craned around to see what we were leaving on the blacktop. There was no chance of him driving on to Canada. It also had a broken window, so a bunch of loose papers in the back took flight and flapped all around like somebody’s wits. I grabbed at the air until my fingers got hold of one. A tattered sheet covered with drawings of faces. They were not caricatures or cartoons but fast portraits. All the faces were different, but their expressions shared a certain exasperation. Nonplussed. When we pulled back in behind the house the papers settled to rest. Kellan eased into the yard and shut off the engine. I helped him gather the drawings.

“These are good,” I said—I’m no judge but anyone could see their humor, stubbornness, life. They held your eye. They seemed to lean out from the page as if meeting you partway.

Kellan allowed he made the drawings to put him at ease. Plainly they also embarrassed him, and he shuffled them up in a pile and tied them with a twist of string from the glovebox. Then he asked could I drive him down to Greenstone in my less-derelict car to look for parts.

I didn’t really want to at first. It was Saturday, and my band Red Dog had a gig later. On playing days, I liked doing things for Lark or working on the sailboat in the shed a block up the street. More later about the boat, which actually needed some hardware—chain plates, turnbuckles, a good marine-grade compass. All of which might be found on a lucky day in Greenstone. Besides, it was nearly planting season—I could visit the seed merchant. Also the Fair can be hard to navigate your first time or two. Also I liked Kellan. His plucky doomed optimism, his drawing habit and rooster hair.

“Let’s go then,” I said.

We drove southwest on the expressway. The term is residual—a level road once, now it’s seamed and holed, with shoulders of pavement sagging into the ditch. There’s a spot where two flash floods in a month blew out a culvert, then a third came down and tore away sixty feet of blacktop plus the rubbly subgrade beneath it. Though technically it’s a state highway, the state first ignored our complaints, then told us they were “seeking to allocate funds,” then promised to repair the break but never did. That’s what you get for living up here. None of the major families reside on the shore. Some still vacation nearby, but these are not people who travel by car. You might see their helos whacking past on long weekends. Sometimes they fly low for an intimate glimpse of citizens on the ground. I used to wave but they never waved back. After more than a year a pair of loggers, a basement contractor, and a retired mining engineer showed up with their skidders and chainsaws and a cement truck with rotating drum and rebuilt the missing section with pine logs and concrete. They also arranged for forty linear yards of black-market culvert, which arrived in the dead of night and was lying in the ditch at sunrise. These adults set the world right again in thirty-six hours asking nothing in return. I will say you don’t want to hit that stretch doing more than twenty-five.

Kellan relaxed, underway. From being loathe to mention family he began describing them in bright vignettes. His restless uncle Vern who designed a plan to fabricate roofing shingles from urban sewage, arid climates recommended. The cousin who disappeared for two weeks and returned hairless and speaking in holy tongues. A mutinous six-year-old niece who filled her stomach with classroom air and burped the Pledge of Allegiance. I kept laughing while he talked. Not everything he said was funny but he was funny saying it.

I began to understand what was familiar about Kellan. He had a kid-brother quality. You wanted to take care of him. He didn’t talk about his hand but wasn’t self-conscious about it either. It wasn’t really a hand anymore. He couldn’t hold a fork with it or a pen, though later I would see him successfully clamp a large paintbrush in it, swiping back and forth. Sometimes while talking he’d reach up with the claw and scratch the side of his head. It looked great for that. I tried not to ask questions that would pin him down. Given his gaunt frame and the way he looked around as if for ghosts or grim authorities, I assumed he was a squelette or fled menial who’d signed for the usual six-year term and found conditions unbearable. But then he suddenly volunteered that he was trained in microbiology, specializing in food science.

“A teacher singled me out. An aptitude for chemistry is what she said. Wanted me to design dietary supplements. For the astronauts, that’s what got me. Astronauts! That’s where I thought synthetic proteins might take me.”

At this, my breath caught. As far as I knew, there hadn’t been a space program since it had failed—decades ago—to return a profit for investors. But I was wrong! The final frontier still beckoned! I asked him about it.

“Ha, no.” Seeing my excitement, he gently informed me astronaut was the prevailing idiom for the sixteen or so families who ran coastal economies and owned mineral rights and satellite clusters and news factories and prisons and most clean water and such shipping as remained.

I tried not to show my disappointment, but what a letdown! Bummer city as great-uncle Norman moaned in his long twilight. And sure, of course Lark and I had media once—internet, TV, the vivid suspect world delivered secondhand, ready always to predict our moods and sell us better ones—but we were early abandoners. A great many idioms got past us.

Obviously, Kellan went on, the way to prosper was to work for the astronauts. You wanted to be needed. You shot for indispensable—indispensable was the goal—but then for all his aptitude Kellan never met an astronaut, never achieved this fabled career path. He did get a position on the line manufacturing freeze-dried entrées for their bull terriers but breathed some bad fumes in an industrial fire and got real sick, so they let him go. The topic shut him down, and we traveled the last few miles in silence.

I was confident Greenstone would pick him up. Icebridge can be dull, but Greenstone on a Saturday flies all the colors. It’s medieval in the best way. You roll in on 61 to a huge cloud of steam tumbling off cauldrons of fish and root vegetables boiling at Lou’s—alluring, but there’s even better fare out on the pier, the ancient ore dock where train cars once dumped taconite into the holds of ships. That was decades ago, but the dock’s still there on its bony pilings to host whatever is needed.

We parked a few blocks up the shore and walked past old cars and trucks, thin horses eyeing each other’s rumps, a pair of oxen with runny noses and bags strapped under their tails to catch the exhaust. Weary hounds rested under a tree in which a gray parrot muttered cavalier indecencies. Pennants snapped in a rising breeze. I was real happy, but Kellan looked doubtful about the whole enterprise. Admittedly Greenstone looks like a place where you might find trumpets, goats, jesters, and pies baked with four and twenty blackbirds but maybe not a specific vintage auto part. Still it was Kellan’s best chance without a risky haul south or waiting weeks for uncertain delivery.

The pier reared up over us as we approached. I never tired of this canopied street on tarry black stilts rising out of the water. Tents and signage in all hues from shore to terminus twelve hundred feet out, a stretched circus of brilliant conniving hawkers and traders and painted insignias and hens in small cages saying Aw? Aw? A buttressed ramp rose in a gentle curve to the high dock—the ramp lined as usual with musicians, many of whom I knew and nodded to as we wound up through them: my friend Manny Panko with battery amp and reverse-body Gibson playing a credible Mozart/Tom Petty fusion, the slap-bass maestro Darby Slake riffing in ways I could only envy. Face painters were decorating old people for free, so the pier was peppered with ancients guised as penguins and armadillos and oddly sorrowful tigers. We continued plying up through the merchants, stepping under their tents and out onto cantilevered platforms perched over the forty-foot drop to the water—flowers, baked rolls and pizzas, leathered oddments of cameras and ocular gear, drifting clouds of spun sugar, old clothes and kitchen knives and reclaimed paraffin and tabletop radios including a wood-paneled Sony playing news of the world from the BBC, none of which had much bearing on invisibles like ourselves but maybe pertained to astronauts. I bought a sausage made by Narlis Newcomb, whose permanent shop was a few blocks inland and whose gigantic pigs were riveting to watch, snorting and humping and rooting around their murky acre.

Watching me closely, Kellan bought a sausage too. He seemed unequipped to be out on his own. Besides his youth, his burnt talon and chicken hair made him look terribly vulnerable. I never had a kid brother and always felt the loss. The kid brothers in books and movies and obsolete comedies were forever screwing up, getting bullied, stealing candy, wiping boogers on the wall, telling obvious lies with dire cost to neighbors and crochety relatives. I always liked those kid brothers, noxious yet somehow innocent. They often seemed lucky at first, until the lies or the boogers caught up with them. In all cases they were worth protecting, often needing the occasional dose of guardrail wisdom. I resolved to keep an eye on Kellan as he wended his way toward the automotive booths set up halfway down the pier, just before the brewers and distillers and hemplings in their knitted hats and the low-stakes cheaty games of chance.

As always there were half a dozen auto-parts vendors whose inventory changed constantly: piles of tires and rims, sparkplugs in grubby small boxes, sleek bruised all-or-nothing lithium batteries. Kellan pulled a slip of paper from his pocket with “ball joint” written on it and a series of numbers, and here’s what I mean about kid-brother luck: the very first vendor, a woman called Grabo whose knowledge was vast and whose long hair was plaited into flat kelpy strands, took Kellan’s note and nodded him toward a waist-high crate of miscellaneous bits. Kellan leaned over the crate and raked around with his claw.

I was about to say hi to Grabo when another customer surged ahead. A bruiser by any measure, holding a set of disc brakes and demanding a discount. There’s a blunt tone people take who are used to deference. Grabo was eighteen inches shorter than the oaf in question and gazed at him unmoved.

Stepping aside I recognized the man. An officer of the law. Apeknuckle we called him. My God he was massive. Even off duty he made me uneasy. I glanced over at Kellan. You never want the law near a kid brother, but then Apeknuckle was busy trying to bully Grabo. She was normally a ready bargainer, but her pride was up and she stuck to her price as Apeknuckle swelled and purpled. Only now did I notice that Grabo held in her hand a sort of modified crankshaft. It was strangely graceful with most of its flanges sheared away and she used it to gesture and reinforce her argument. What a clear low voice she had. What a sinewy forearm. I don’t know what Apeknuckle said to Grabo then, but he did lay hands on her. To that I will attest. Quick as eyesight Grabo whipped that crankshaft around and down went Apeknuckle with his knee the wrong way. He didn’t yell at first but when he tried getting up there came a bright snap after which it was shrieks to raise your hair. Even knowing what he was you had to feel for him, bucking and roaring and trying to make the knee regular again, while several nearby vendors lined up next to Grabo in solidarity—one offered to give Apeknuckle another tap, if that was what she wished. You’d think the scene might drive customers off but not really. If anything more came crowding. Only Kellan was spooked enough to scurry away, and I was glad he did, a kid like that with no reserves. In fact the two of us backed off, watching the crowd make room for an electric cart carrying two medics who knelt down looking gravely into Apeknuckle’s face. One administered a tiny injection and the great brute went silent and rolled up his eyes while they lifted him to a gurney. As it trundled past a boy of ten reached out and gave Apeknuckle’s nose a hard twist for later.

After this excitement we repaired to the stall of a local brewer who’d won awards in former days and still made a malty stout you could eat for breakfast. I asked Kellan if he had found the right parts for his Ford. No, but on the way back to Grabo’s we got sidetracked by a little darts game in which I lost a few dollars, and that made Kellan buoyant enough to lobby for a second pint. Then we got hungry and worked our way back toward the food stalls. Market day gets away from you if you let it. In my carelessness I nearly stumbled over a stack of tabloids tied loosely with twine.

It was the latest Mosquito.

I didn’t much credit the Mosquito, a humid little twelve-pager of raggy pulp and irregular publication. It styled itself a rebel paper, making much of the danger it posed to what Kellan would call the astronaut class. Most of its articles appeared under wiseass pseudonyms like Paulette Pinecone and Freddie P. Squirt. The Mosquito wanted to antagonize power, but that’s a tall order when you won’t name sources and also can’t spell. Reading was on the ropes anyhow—who pays attention to a newspaper that doesn’t proofread its own masthead?

the MOSQUITOdistrubing the sleep of kings

This edition however had a story about a group suicide in Green Bay. I knew people in Green Bay. I picked up the paper. The suicides were high school age. Five girls, three boys. They did it at one of their homes when the mom was out of town. They played some music, had a nice meal, and ingested the pharmaceutical known as Willow, a rising star in the market of despair. Willow was named for the sensation it was said to evoke of climbing through alpine tundra toward whatever comes after. The story included a quote from a heartbroken friend of the dead. The boy was twelve. He felt betrayed they had gone without him. It wasn’t suicide he said. It was exploration. He said Earth was all but done and they wanted to see if another world existed as some claimed. They’d been working up to this. Like all explorers they had a credo. Go in search of better.

My eyes blurred. I threw the paper in a bin. I’d heard of this Willow toxin before—Labrino had talked about it. He wanted to get some, put it in a drawer. Hoard it for when things got untenable. The day was turning dark until I became aware of a sturdy presence speaking in a friendly way. Narlis Newcomb had joined us. He was carrying a jug of water and heading back to his booth. Narlis, farmer and pork virtuoso, was describing to Kellan his own arrival in Greenstone, his harrowing flight from the sectarian South, his joy at snow. He was easy to be around, reassuring, a man with the dignified brow and reasoned speech of a Roman citizen. It always picked me up to listen to Narlis. He was protective of his friends and thought all kids were his own.

Narlis wanted to plan a dinner. It was his cure for everything, and he might not be wrong. Narlis threw dinners that started small and spread like news. While we talked Kellan drifted back up the pier, a veteran already of the Greenstone Fair and easy on his feet. He soon reappeared looking delighted. Cradled in his claw was a slight bronze disc whose lid opened to reveal a working compass, its red needle pointing roughly north.

“Is this what you were looking for?”

Kellan was so pleased with himself I couldn’t say no, even though what the boat really wanted was a liquid marine compass that would mount securely in the cockpit. This one was more suited to a kid’s pocket on a day hike. But how thoughtful! He laid it in my hand. I held out some money he wouldn’t take. He said he owed me for the time and trouble. I asked whether we shouldn’t go back and have another go at Grabo’s box of miscellany, but Kellan claimed a stomachache and asked that we head out.

While we were driving back to Icebridge Kellan’s fretfulness returned. He fell quiet and I let him. I was thinking about the innocents in Green Bay. I couldn’t stop imagining their voices, their pale hands and bluing fingernails.

Then Kellan stirred and looked over at me. “I like your butcher friend.”

“Me too.”

He said, “This would be a good place to stay if I could.”

“Maybe you can,” I said, my mood lifting.

“I can’t, though,” Kellan said, looking out the window. A bird was flying low beside the car, keeping up with our speed over that rugged stretch of road. “No I can’t. I’m what you think I am.”

“All right.”

“Squelette,” he said as if insisting that I understand.

“All right.”

“Rainy,” Kellan said, “you going to give me up?”

“No.”

“There was no staying in that place,” he said. “Not one more day.”

“Best to leave out details.”

“I made it to a friend’s house. She threw a coffee cup at me. Said I had a six-year contract and what kind of person gives that up?”

“What kind does?”

“The kind that won’t die in captivity.” Gazing out the window he added, “Why do people think we look this way?”

His reflected face and collapsing posture looked so bleak I fell into the old quixote habit of resolving to do whatever I could for this poor kid, whether he stayed or left and at whatever cost to me, which gave me a pious glow all the way home. Then Kellan tripped walking into the house and three heavy automotive chunks dropped out of his jacket and hit the wood floor like cannonballs.

He feigned astonishment, clawed at his scalp, claimed he’d only tucked the parts into his coat for convenience. “I was about to pay for those ball joints,” he said. “Then that big fight! Guess I got scared and forgot.”

“You didn’t forget—those weigh more than your head,” I pointed out.

“Sometimes I disremember,” he said, “ever since my injury.” He held his ruined hand up in the light to glint.

I didn’t buy it, but once you begin excusing someone it’s easy to continue. He said he was sorry and took out a billfold and set cash on the table. Said he’d be grateful if I would go back next week and pay Grabo on his behalf. Next moment he wondered if I might assist him tomorrow installing any of these ball joints. To help him, as he said, “tame the Ranchero.” Then he would be on his way.

I thought about this during the evening, while Red Dog played the Lantern. It was a good night for Labrino, the house pretty full, no fights that I saw, our drummer Harry Lopes happy at the moment and therefore playing a nice tight set.

And yet I was unsettled. Much as I liked Kellan, I had to wonder if Lark and I were falling into something here. Some hole deeper than would be easily got out of. I found myself playing only familiar bass lines, staying in the pocket, doing the reassuring walk-ups and resolves, seeing in my head a series of endings in which cloud banks dispersed and I stood with Lark in the slanting sun. In one sequence, during a three-song set where the blues evolve to balladry then exuberant rock and roll, I had the briefest glimpse of us launching the old sailboat on a day when the sea had put away her crown of lightning, and I startled the band by laughing into a live mic, a sudden soft bark. I laugh when I’m happy, and getting home that night I laughed again, for Lark was waiting up to show me a series of sketches Kellan had done that evening—of people he’d seen on the pier, of thistly Grabo and looming Apeknuckle, which Lark giggled over even though she felt bad about his knee, and finally one of Lark herself, a fine-lined sketch in variegated ink, light sepia at the edges darkening to coffee. He’d captured her joy and untamable hair and even the scarlet grandeur of her cheekbone birthmark—it had a gentle S-curve like a river glyph. Some saw the mark as a flaw or deformity but Kellan obviously loved it as I did. That spoke well of him, wouldn’t you agree? Like the others, Lark leaned out from the page. She shone and sparked. She seemed about to speak.

when a flame is lit, move toward it

WHEN I MET LARK there were two things I had to do, two ideas to embrace or lose my chance. Reading was the first. I could read but rarely did. My parents, ahead of their time, had little use for books, so I grew up a knockabout. It’s fair to say in my case size preceded sense. I wasn’t a bully—well, probably sometimes. I’m not without regrets. Call me a genial fighter, a boy of six words, a lummox grinning over pancakes. Adults mentioned my appetite and big hands, my aptitude for labor. In a grade-school Robin Hood play I was Little John. What a good role. I took to it naturally and suppose I never really stopped.

By age twenty-eight I was working as a house painter and sitting in with two or three tavern bands in Duluth. At noon one winter day I left my job detailing a stucco high-ender with hardwood moldings and a crenulated roof like a battlement. Embarrassed to eat near the meticulous homeowners I strolled a few blocks to the library for a covert lunch in a study carrel. The carrel was around the corner from the help desk where a woman with a quiet radiant voice explained technology to ancients. There didn’t seem to be any nonancients in the library that day—only her at the desk and me, who just wanted a warm place to eat a cheese sandwich. Crane as I might I couldn’t catch sight of her, which only made her voice more arresting. The library had recently scaled back its services, and there was a long shuffling queue waiting for assistance. What happened to their online therapeutics? Why had their credits been refused? Their inquiries were nervous, angry, imperious, frightened. Her voice in reply was low and melodious. It settled them, reminded them they were in the right place. I hadn’t felt anxious at all, sitting at my carrel, yet I too felt soothed by her delivery and shut my eyes to listen. Almost right away it became impossible not to imagine hearing that voice morning and night. A voice that was the opposite of panic. On my way out I tried again to glimpse its owner, but she was obscured behind a mammoth gesturing clergyman filing a subversive-materials complaint.

Same carrel next day, another cheese sandwich. I went back hoping to hear again that easy low music, and sure enough there it was, addressing the agitation and pain of the fearful. This time I sensed a trace of humor or affection down inside her voice. Again I was stirred by a nameless melancholy, by envy for those who lived within that frequency. I didn’t think of it in those words. Picture a voice like a river’s edge where the water turns back on itself, orbits quietly, proceeds downstream in laughter. This time when I left she had gone on break. Again I was denied the sight of she who had beguiled me.

In later visits, I paid attention not just to tone but to content. Pulling books as camouflage I took a carrel nearer her desk though still out of view. She did far more than direct people to charts and information. She had a way of answering unasked questions, finessing and adjusting her recommendations. History for the ambitious, novels for the lonely, poetry for the heartbroken. All of it a lettered world alien to me. I began to take notes—“Dickens,” she replied in a near whisper to one request, and dikens I wrote in stub pencil. Why, you ask. How would I know? When a flame is lit move toward it. Titles, authors, barely floated notions—whatever she said that’s what I scribbled. I didn’t yet know the word oracle but she had that smoky appeal. There seemed no person she couldn’t understand, no question too dead to resurrect. She told a bored girl about a sixteenth-century poet whose goal was to read everything ever written. Think about that. The girl did not believe her but I did. Apparently this poet went blind in the attempt. Luminous is another word I didn’t know.

I finished the affluent stucco but kept eating in the library. By now I’d affected a nonchalant stroll past the information desk and found to my increasing turmoil that even beyond her bewitching voice I wished to look at her forever. Her twisty dark hair fleeing its restraints. Her wine-dark river’s kiss of a birthmark. Chancing a single casual glance at her green eyes, I got an impression of curiosity and wit and maybe a little mockery zipping around back there like fireflies.

In desperation I acquired a notepad and ballpoint and expanded my use of the library to actual books. Dickens turned out a hard go (Twist, no, the beatings go on and on) but I stuck with it. Next writer on my scrappy list was this woman Connor whose people were confused and malformed and placed in the world as if by the god of cruelty. I could hardly bear those stories, yet linked together they became a rope ladder you climbed with knees and elbows out of whatever dragged you down.

After this I seemed to enter a zone of madness. It’s a blur now and was then. I couldn’t afford not to work, so to sustain the madness I worked badly, falling into books while latex congealed on my brushes and rollers. Not everything caught but some did. I loved the crazy fight where Beowulf goes hammer and tongs with Grendel in the longhouse, gripping the monster’s arm like the world’s first clamp and finally tearing it off, hairy shoulder included, and hanging it in the rafters to drip. Holy smokes! I was taken in too by the long boat ride of Odysseus with its thousand interruptions, Circe with her ominous pig yard, what had to be an invigorating layover with Calypso, and the startling wit of the cyclops announcing a nice surprise for Odysseus but then guess what it was: You shall be eaten last! Well, come on—painting jobs thinned into the distance as these stories swallowed whole afternoons, a dazed reader rapt in stormy light cast by Lake Superior that raging autumn when the sun got lost for seven weeks straight in a rack of permanent clouds. I banged and barged through dozens and hundreds of books discovered in my eavesdropping sessions, not just adventures but also poetry, sweet Jesus, by Greeks and Brits and Japanese whose silky names I never can remember. Did I understand it? Not by half, but when it thunders you know your chest is shaking. These thieves and lovers and wandering poets—what big lives they had! I began watching everyone I met for secret greatness. I read about vanished glaciers in books of scorned science, then a monograph by the raging climatologist Holloway who predicted Lake Superior would shortly warm enough to yield bodies that had lain on the seafloor for centuries—“the navigators, cooks and ancient braves, the unlucky swimmers of antiquity.” And sure enough Holloway hadn’t been gone a decade before these dead began coming ashore, washing up in the shallows, waxy and gaping in their period clothes, frightening children on the beaches and once tripping up a fleet of racing yachts as they foiled to an upwind mark. After Odin traded an eye for knowledge I had eight days of sympathetic response where my own left eye went dark. Recalling the poet gone blind in his zeal I considered taking a breather, but by then was deep in the tale of a minotaur who falls for an American waitress. I couldn’t bear the suspense. Would they find happiness together? I bent down to the pages with my solo eyeball blinking constantly to keep from drying out. Reaching the end, I discovered I still had both eyes after all—they both worked fine, and in fact were full of tears.

It was in this time of compulsive immersion I read the work of Molly Thorn, whose name popped up more than any other in my scattershot notes. It wasn’t even her real name, Lark later confided, but rather the alias by which she safeguarded her prized and peculiar family. In any case her work was hard to track down. The library had some Molly Thorn poetry, an essay collection, and the single versified novel Lark described to one reader as “tangy,” but all were loaned out. After asking a few local musicians I learned a drummer named Sunderson had the novel. Fairly sure he never read it. Accepting a few dollars he passed it to me in a crinkled brown bag, looking at my eyes with suspicion. By this time of course reading itself was slipping into shadow. There was a sinuous mistrust of text and its defenders. The country had recently elected its first proudly illiterate president, A MAN UNSPOILT as he constantly bellowed, and this chimp was wildly popular everywhere he went. Once during my days in the carrel a belligerent crewcut approached Lark’s desk barking that reading was “a dark art,” and she lowered her voice, saying it was the darkest of all and wouldn’t he love to try it? I don’t remember his reply, only his shaggy hoarse tone shaking with ignorance and desire. I wondered did I sound that way and if so how to stop.

Since those days, Lark had managed to locate everything of Molly’s except this rumored volume, I Cheerfully Refuse, which was on the docket when its publisher sank like the last of a shocked armada. Maybe a few hundred of these advance copies survived. Some said it was a memoir, some said a parable in response to the short period in which so many things counted on went away. A onetime book scout of Lark’s acquaintance described it as a covenant with the forthcoming. A vow to creatures not yet conceived. I was glad for Lark to have got hold of it at last, but apprehensive too. The perfect book remains unread.