Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Salt Modern Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

Irish Times: Books to Look Out for in 2025 This collection of stories, written especially for BBC Radio 4, includes a ten-part sequence: 'The Circus', set around Cliftonville Circus, where five roads meet in North Belfast. It's five minutes from the nationalist Troubles flashpoint of Ardoyne, where Paul grew up. It's close to Holy Cross Girls' School, where protests targeting primary school children drew international attention. The Circus is situated in the poorest part of the Belfast – it is also the most divided. Each road leads to a different area – a different class – a different religion. The Circus explores where old Belfast clashes with the new around acceptance, change, class and diversity. But this is 2024 and a fresh energy exists. Other stories include 'Tickles', a story about a man visiting his mother in a dementia ward where he finds he is the one who had forgotten important things; 'Cuckoo', about a man's collapse and surgery – where he feels something more sinister has happened to him; and 'Daddy Christmas', where a gay man writes a letter to the son he never had.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 149

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR I HEAR YOU

‘These moving short stories are brave, honest, raw and funny, doing what fiction does best, showing us the lives of others and in so doing showing us ourselves. Wonderful.’ —KitdeWaal

‘The stories in IHearYouare full of tenderness and fun, reality and rawness. In every one, there is humanity and wisdom. As a reader, you are in for a treat because Paul McVeigh is a born storyteller and his imaginative vision is compelling.’—WendyErskine

‘From a son paring the bunions on his mother’s feet to a man’s soul getting sealed out of his body, and culminating in a deft interlinked cycle, the stories of IHearYouare warm, frank and unsentimental, bursting with character and idiosyncratic detail, written with Paul McVeigh’s characteristic geniality and Belfast wit.’ —LucyCaldwell

‘This is a world of escape artists and fraudsters, of body swaps and comedy cuckoos, of misfits and trespassers of every ilk. We are moved and entertained in equal measure by the antics of the spangled cast of “The Circus”, a club that is peopled, in the words of Dockyard Delores, by ‘the freaks, the fruits, the rejects, the weirdos’. Where else would you want to be than amongst the outliers, where the tender, the vulnerable and the brave reside? There is no better company to be in.’ —BernieMcGill

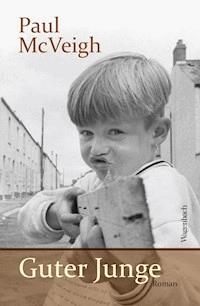

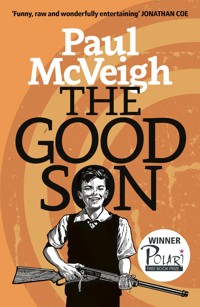

PRAISE FOR THEGOODSON

‘When I think of exceptional working-class novels from the last few years, I inevitably think of Kit de Waal’s MyNameIsLeonand Paul McVeigh’s TheGoodSon.’ —Observerii

‘Blackly hilarious (with) one of the most endearing and charming characters I’ve come across in a long time.’ —ELLEMagazineBestof2015

‘The backdrop is one of poverty, paranoia and violence, both sectarian and domestic … there’s no nostalgia in the depiction of simmering brutality and intense claustrophobia … a full-colour close-up of life in a no-go area. Heartbreaking … gripping.’ —Guardian

‘Paul McVeigh’s debut new novel is everything its fans say it is – funny, raw, sometimes distressing, always wonderfully entertaining. The young Mickey Donnelly is a superb creation, his thoughts and feelings bubbling onto the page in an immaculately-rendered voice, droll, cheeky and authentic. McVeigh renders a child’s view of a very adult nightmare with bewitching empathy. You will love every moment of it.’ —Jonathan Coe, author of TheRotters’Cluband WhataCarveUp!

‘Pungently funny and shot through with streaks of aching sadness. Scenes from it are going round in my head months later. Paul McVeigh’s is an original voice of which I, for one, can’t wait to hear more.’ —PatrickGale, author of APlaceCalledWinterand NotesFromanExhibition

‘One of those books that’s written in such an accomplished and natural way that it seems not like a book at all, but a perfect, fully-formed rendering of reality through another’s eyes. It’s a triumph of storytelling, an absolute gem.’ —Donal Ryan, author of TheSpinningHeart

PAUL McVEIGH

I HEAR YOU

DedicatedtomybrotherAlexwhoheardme.

Contents

Introduction

The stories inIHearYouare in chronological order.

Tickles was the second short story I’d written, and my first for radio. I was commissioned by BBC Radio Ulster producer, Heather Larmour, and it aired on BBC Radio 4. Although this was the only time we worked together, Heather met with me many times and, over many conversations, mid-wived me through writing for radio, teaching me so much about the medium.

‘Cuckoo’ was my second story for radio, commissioned by BBC Radio Ulster producer, Michael Shannon, who commissioned all the stories printed here, in fact, bar ‘Tickles’. It aired on BBC Radio 4.

‘Tickles’, a story about Mother and Son, then resurfaced, chosen as Radio 4’s Mother’s Day story and was used, shortly after, by an English vicar as the basis of his Easter sermon.

The third stand-alone story in this collection, ‘Daddy Christmas’, aired on Christmas Day.

There’s a number of things that you have to adapt to when writing for radio, for example, the story slot is xivfourteen minutes, and that translates to, roughly, 2,000 words on the page. The story slot is 3.45 p.m. in the afternoon and is to be considered in the story theme and language used. As an ex-teacher school run time was also on my mind.

‘The Circus’ was a challenge, with a number of firsts for me. I was commissioned to write ten linked short stories with an over-arching storyline, and also, in the post-lockdown world, there was a desire for the story and overall tone to be upbeat.

Writing for radio excited me as coming from a theatre and comedy writing background my ear was tuned to dialogue and oral story telling but it wasn’t until I met Cathy Galvin and attended the first Work Factory Salon in London, that I fell in love with short stories. One night a month, short story lovers would gather in a tiny bookshop in the back streets of Soho and listen to the best writers in the country reading their work out loud. Cathy’s Word Factory forever entwined in my mind the short story form and hearing a story read aloud, so it’s perhaps no surprise that my first collection of stories should be those I wrote for radio.

I HEAR YOU

Tickles

Mum thinks I’m Dad. She’s holding me and won’t let me go. I could be wrong, but the way she took me by the arms and stared into my eyes before she hugged me, there was just so much love. I’ve only ever seen her look that way at one person. And you have to give it to the man, even in death, even through Mum losing her mind, he’s still making her happy.

I’ve tensed up. I don’t want her to notice and hurt her feelings. I wish I could just let it happen and feel it. Take the affection and pretend it’s for me. Steal love from a dead man. Or pretend I’m him, for her.

Is she even in that moment any longer? Maybe she’s forgotten who it is she’s hugging and why? Staying still out of embarrassment, hoping it will come to her. I shuffle round to catch a glimpse of her face in the window of the conservatory. I’ll know then. We sway like awkward teenagers at a dance, but Mum won’t turn. Feet planted, her hug tightens.

I feel claustrophobic. For years I hugged Mum and felt her freeze. Tolerating my touch but never returning it. And not once did she initiate it. I’ve only started hugging her again since she’s been gone. 2

Voices approach. I pull away, gently, giving the polite signal, thatwaslovely,Mum,butenoughnow, but no reaction from her. What is left of her in there? Even the humiliation of public displays has gone.

Two women enter the conservatory and break off their chat to look at us.

‘Ach, hello,’ one says, as they head towards us.

I smile and nod, rolling my eyes like, youhowitis.

‘How are you?’ She stops beside me.

‘Fine.’ I push away firmer, but Mum squeezes me tighter and now I’m out of view of the women.

‘How’s your mammy?’ one asks. I twist my neck, but all I can see is the side of a head and one huge hooped earring. I imagine a little parrot perched on it, swinging to and fro.

‘Great,’ I say and give up straining to make eye contact.

‘Ach,’ I hear, and the two women shuffle into view to nod at me. One nudges the other.

I’ve no idea who these women are. Could be Belfast banter. Have I met them in here? Or maybe they know Mum from before everything.

‘So, you’re back then?’ The chatty one shows no signs of moving on.

‘Yeah, for a few days, then work, you know?’ We’re all pretending it’s completely normal to hold a conversation while crushed in a WWE death grip.

‘Ach.’ She looks to the other one, who nods and smiles at me. ‘How’s her feet?’

I search my mind for a link. ‘Great.’ I smile. I don’t know what she means, but I want them to go away.

‘Sure, I’ll let you go,’ she says, without irony.

‘Ok, all the best,’ I reply, with an awkward wave. 3

They smile, nod back and head on. Why is it when I talk to people from Belfast, I feel like I’m in a bad Irish play?

I hear them continue their chat in quieter voices until I’m left in silence with the hug.

‘OK, Mum, now, come on we go for a walk.’ I pull away – no nonsense.

‘No,’ she says.

Goosebumps tickle me. Her first word in ten years. Since Dad died and she got sick. She’s coming back. Some of her. She thinks I’m Dad and she’s coming back for him. She’s holding on for dear life, afraid he’ll leave her again. Or maybe that moment’s passed too and she’s afraid that if she stops hugging and pulls back it won’t be his face she sees. How heartbreaking for her that it will be me.

My shoulders have risen to my ears. I’m not enjoying this. I’ve had enough. Mum rubs my back. Oh God, it’s not going to get funny, is it? If she does think I’m Dad she might get frisky.

I breathe out long and slow like I’ve been taught.

Mum gently strokes my back. I can just feel her fingertips through my thin shirt. Tickling. Inside me there are shifts and turns, I feel them, like a combination lock clicking into place. The nursing-home smell of toilet and school dinners is overpowered by that of dust burning on bars of an electric fire and the fusty smell of old carpet getting warm. I close my eyes and see dark red, floral-patterned wallpaper and a faded-brown, threadbare, Persian-style rug on the floor.

How’sMum’sfeet?I think. 4

Ma’s just in from work. ‘Do your Mammy’s feet,’ she says, wrestling with her shoes.

I turn on the electric fire with the plastic coal flickering from a spinning fan over a red bulb. The second her shoes are off, Mum collapses on the sofa like the shoes were a stopper and all the air’s been let out of her.

I’m in the kitchen filling the washing-up basin with scalding hot water from the kettle, adding those mysterious healing salts from the cupboard under the sink. An old newspaper from the coal hole is placed on the floor between her feet. I fetch the special knife, and the good towel that’s still fluffy. I carry the heavy basin, water sloshing up its sides.

‘Be careful with that, wee boy,’ she says. My eyes widen, my tongue out of my mouth, my teeth clamped down on it. I did this to stop me daydreaming. Pain kept me present. Mum had taught me that many a time with a slap.

‘Are you trying to kill me?’ Ma shouts as her feet touch the water.

I chuckle, bringing me back to the nursing home. I laugh into Mum’s shoulder, and she hugs me tighter. Now I could cry – hearing her voice again in my head. Even when I dream of her she’s silent. I’d forgotten how she sounded, like people say they forget the faces of the dead. And now I have it – her. Connected from just one word.

‘How are your feet, Mum?’ I ask. She doesn’t respond.

I think about biting my tongue. Do I still do that? No. Through years of yoga and meditation I’ve learned other ways to stay in the moment, other than hurting myself. But 5breathing hadn’t come to Belfast back then. Like olives and garlic and women driving cars.

I’m happier – settling into this holding. I mean, it’s a nice thing to do. For her. If this is what she wants. So what if I’m pretending to be my dead Dad? I’ve never heard of anyone doing it, but I guess it’s not the kind of thing people talk about.

Will she say anything else, not only now – ever? I take my arm from around her shoulder and search for my phone in my pocket. Mum grabs my arm and puts it back around her.

‘I’m just getting my phone,’ I say. I want to record her. Before I lose her again.

‘No!’ she shouts. That’s me told. I laugh.

She spoke again. I feel like a father hearing his child’s first words. No, that’s just weird.

‘Mammy, how’s your feet?’

She doesn’t answer. Mum’s feet. Wow. They were seriously ugly. They could have been used on warning posters in GP surgeries for smoking, excessive drug use, or some flesh-eating virus caught from exotic travel. Bunions, corns, little toes the size of knuckles and big toes with joints like elbows.

I’m sitting on the carpet in our old house, the one I had to sell to keep Mum here. My legs wrapped around the basin, staring at her. She’s bright red, forehead sweating, and those mysterious salts have turned steam into magic vapour. She’s under a spell, transported to paradise.

I put my hands in the scalding water and lift a foot out. I test an area of her heel by running a fingernail along it, 6to see if the hard skin has softened, and skin peels. With the knife I scrape the hard skin, watching it curl like a hot spoon along a tub of ice-cream. I do the thickest areas first, on the heel and the ball of her foot, then the delicate areas at the side. I work until her skin feels smooth and even squeaks.

I hear voices walking past me in the nursing home, but I don’t look up. Mum’s tickling my back again and I don’t want to break it. What if shebreaks it? Stops holding me?

My lungs fold.

Breathe. She might never hug me again.

Deep,slow,breath,in.

This must be to do with Dad. She would be more hereif he was still around in some way. A reminder of what she lived for. Maybe I could pretend to be him when I come. What am I saying?

Deep,slow,breath,out.And another.

If he was the reason she ended up here, isn’t it possible I could use him to reverse it somehow? Even just a little? I know he’s dead but …

We had been expecting Dad to die. He had been disappearing from cancer for a few years. Said our goodbyes a few times. The doctor said Mum’s early onset of dementia was triggered by depression and grief. He didn’t know that Mum lived for Dad. She was devoted to him. Her mind was wired – set to him. Pleasing him was behind everything she did. Her love for him was a like a thick fog that made it hard for her to see anyone else. Mum lost her mind when Dad died, but from the moment she met him, 7I don’t think her mind was ever hers again. And when he died, her brain turned off. Her body abandoned like a toy without its batteries.

I come back from the kitchen with the talc to see Mum half asleep, whilst sitting up, on our sofa.

‘Lie back.’ I guide her, lifting her feet. I sit, slipping under her legs and resting her feet on my lap. I stroke her legs with my fingers. I kept my nails long for it. Barely touching her, I run my nails along varicose veins like long, purple branches. Tickling her.

‘That’s enough, you,’ she says, impatient with the pleasure, even in half sleep. Happiness was something to be had for a few moments. Not to be indulged in.

Mum’s poor feet … Two jobs, both standing, while Dad sat down at his. Long-distance driving. Long-distanceskiving,I called it. I blamed him for her feet, for her working so hard.

‘Where’s Daddy?’ I asked her. What I was really saying was – he’snothere,heneveris,youshouldn’tbeworkinglikethis,butseehowIloveyou,morethanhim,whydoyoulovehim anyway when he’s never here, even when he’s back fromwork?

She knew what I meant. I know that now. Because of what she told me next.

‘Did I ever tell you how I met your Daddy?’ she asks, eyes shut.

She tells me how she left school at fourteen and went to work in a mill. They made her work barefoot because the floors were so wet. She’d work alongside other girls, nodding to their talk but spent every morning 8watching the clock, waiting for lunchtime. She couldn’t miss Dad.

She’d met him at a dance. So handsome, she said, a snazzy dresser, he could dance like the Devil and charm Death into going next door.

They fell in love.

Dad worked in a factory in town back then and on his lunch break he’d run through the streets of Belfast, three miles to her work. Mum would wait until 1.30 then walk to the small window on the factory floor. She wasn’t tall enough to see out, but could stand on her toes and reach her hand out to wave. She knew he was there, on the street below and imagined him waving back.

My father would watch her wave, he told her, and wait till her hand disappeared back into the little square on the fourth floor, then run all the way back to work again, through Catholic and Protestant areas alike, risking his very life, just to see her hand.

I didn’t believe it. Dad’s side, I mean. She was waving to an empty street. He had made a fool out of her.