Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

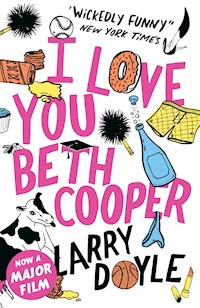

The hilarious first novel from Simpsons writer Larry Doyle - and soon to be a major flim directed by Chris Columbus and starring Hayden Panettiere. Denis Cooverman wanted to say something really important in his high school graduation speech. So, in front of his 512 classmates and their 3,000 relatives, he announced: 'I love you, Beth Cooper.' It should have been such a sweet, romantic moment. Except that Beth, the head cheerleader, has only the vaguest idea who Denis is. And Denis, the captain of the debate team, is so not in her league that he is barely even of the same species. And then there's Kevin, Beth's remarkably large boyfriend, who's in town on leave from the US Army. Complications ensue...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 296

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

I LOVE YOU, BETH COOPER

Larry Doyle wrote for The Simpsons for four years before becoming a complete Hollywood sell-out. He lives outside Baltimore and has a wife, three children, and twenty-six assistants, most of whom he calls 'you'.

For more, please see www.larrydoyle.com and www.iloveyoubethcooper.com

I LOVE YOU, BETH COOPER

LARRY DOYLE

Atlantic Books

London

First published in America in 2007 by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022.

This revised edition published in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Ltd.

This electronic edition published in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Larry Doyle, 2007

The moral right of Larry Doyle to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

'Another Brick in Another Wall (Part 2)', words and music by Roger Waters © 1979 Roger Waters Overseas Ltd. All rights for the United Kingdom and Commonwealth administered by Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of Alfred Publishing Co., Inc.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84887 365 0

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House

For my Mom and Dad

IT IS MY LADY; O! IT IS MY LOVE: O! THAT SHE KNEW SHE WERE.

ROMEO DEL MONTAGUE

ERIC VON ZIPPER ADORES YOU. AND WHEN ERIC VON ZIPPER ADORES SOMEBODY, THEY STAY ADORED.

ERIC VON ZIPPER

I LOVE YOU, BETH COOPER

1 THE VALEDICT

JUST ONCE, I WANT TO PO SOMETHING RIGHT,

JIM STARK

DENIS COOVERMAN WAS SWEATING more than usual, and he usually sweat quite a bit.

For once, he was not the only one. The temperature in the gymnasium was 123 degrees; four people had been carried out and were presumed dead. They were not in fact dead, but it was preferable to think of them that way, slightly worse off, than contemplate the unbearable reality that Alicia Mitchell's ninety-two-year-old Nana, Steph Wu's overly kimonoed Aunt Kiko and Jacob Beber's roly-poly parents were currently enjoying cool drinks in the teacher's lounge with the air-conditioning set at 65 degrees.

Ed Munsch sat high in the bleachers, between his wife and a woman who smelled like boiled potatoes. Potatoes that had gone bad and then been boiled. Boiled green potatoes. Ed thought he might vomit, with any luck.

Anyone could see he was not a well man. His left hand trembled on his knee, his eyes slowly rolled, spiraling upward; he was about to let out the exact moan Mrs. Beber had just before she escaped when his wife told him to cut it out.

"You're not leaving," she said.

"I'm dying," Ed countered.

"Even dead," said his wife, at ease with the concept. "For chrissakes, your only son is graduating from high school. It's not like he's going to graduate from anything else."

Tattoos of memories and dead skin on trial

the Sullen Girl sang, wringing fresh bitterness from the already alkaline lyrics, her wispy quaver approximating a consumptive canary with love trouble and money problems. She sang every song that way. At the senior variety show, she had performed "Happy Together" with such fragile melancholy during rehearsals that rumors began circulating that, on show night, she would whisper the final words,

I can't see me loving nobody but you

then produce an antique pistol from beneath her spidery shawl and shoot Jared Farrell in the nuts before blowing her brains out. Nobody wanted to follow that. Throughout the final performance, Mr. Bernard had stood in the wings clutching a fire extinguisher, with a vague plan. Although the Sullen Girl didn't execute anyone in the end, it was generally agreed that it was the best senior variety show ever.

BEHIND THE SULLEN GIRL sat Denis Cooverman, sweating: along the cap of his mortarboard, trickling behind his ears and rippling down his forehead; around his nostrils and in that groove below his nose (which Denis would be quick to identify as the philtrum, and, unfortunately, would go on to point out that the preferred medical term was infranasal depression); from his palms, behind his knees, inside his elbows, between his toes and from many locations not typically associated with perspiratory activity; squirting out his nipples, spewing from his navel, coursing between his buttocks and forming a tiny lake that gently lapped at his genitals; from under his arms, naturally, in two varietals—hot and sticky, and cold and terrified.

"He's a sweaty kid," the doctor had diagnosed when his mother had brought him in for his weekly checkup. "But if he's sweating so much," his mother had asked, him sitting right there, "why is his skin so bad?"

Denis worried too much, that's why. Right now, for example, he was not just worried about the speech he was about to give, and for good reason; he was also worried that his sweat was rapidly evaporating, increasing atmospheric pressure, and that it might start to rain inside his graduation gown. This was fully theoretically possible. He was also worried that the excessive perspiration indicated kidney stones, which was less likely.

I hope you had the time of your life

the Sullen Girl finished with a shy sneer, then returned to her seat.

Dr. Henneman, the principal, approached the lectern.

"Thank you, Angelika—"

"Angel-LEEK-ah," the Sullen Girl spat back.

"Angel-LEEK-ah," Dr. Henneman corrected, "thank you for that … emotive rendition of"—she referred to her notes, frowned—" 'Good Riddance.' "

THE TEMPERATURE IN THE GYM reached 125 degrees, qualifying anyone there to be served rare.

"Could we," Dr. Henneman said, wafting her hands about, "open those back doors, let a little air in? Please?"

Three thousand heads turned simultaneously, expecting the doors to fly open with minty gusts of chilled wind, maybe even light flurries. Miles Paterini and Pete Couvier, two juniors who had agreed to usher the event because they were insufferable suck-ups, pressed down on the metal bars. The doors didn't open.

People actually gasped.

Denis began calculating the amount of oxygen left in the gymnasium.

Dr. Henneman's doctorate in school administration had prepared her for this.

"Is Mr. Wrona here?"

Mr. Wrona, the school custodian, was not here. He was at home watching women's volleyball with the sound turned off and imagining the moment everyone realized the back doors were locked. In his fantasy, Dr. Henneman was screaming his name and would presently burst into flames.

"Let's move on," Dr. Henneman moved on, mentally compiling a list of janitorial degradations to occupy Mr. Wrona's summer recess. "So. Yes. Next, and finally, I am pleased to introduce our valedictorian for—"

JAH-JUH JAH-JUH JAH-JUH JAH-JUH

Lily Masini's meaty father slammed the backdoor bar violently up and down. He turned and saw everybody was staring at him, with a mixture of annoyance and hope.

JAH-JUH JAH … JUH!

Mr. Masini released the bar and slumped back to the bleachers.

"Denis Cooverman," Dr. Henneman announced.

AS DENIS STOOD UP, his groin pool spilled down his legs into his shoes. He shuffled forward, careful not to step on his gown, which the rental place had insufficiently hemmed, subsequently claiming he had gotten shorter since his fitting. Denis had been offered the option of carrying a small riser with him, which he had declined, and so when he stood at the lectern barely his head was visible, floating above a seal of the Mighty Bison, the school's mascot. The effect was that of one of those giant-head caricatures, of a boy who told the artist he wanted to wrangle buffalos when he grew up.

Denis looked out at the audience. He tried to imagine them in their underwear, which was easy, since they were imagining the same thing. Denis sort of smiled. The audience did nothing. They were not excited by, or even mildly curious about, Denis's speech, merely resigned it was going to happen. He met their expectations.

"Thank you, Dr. Henneman. Fellow Graduates. Parents and Caregivers. Other interested parties."

Denis had left a pause for laughs. It became just a pause.

"Today we look forward," he continued. "Look forward to getting out of here."

That got a laugh, longer than Denis had rehearsed.

"Look forward to getting out of here," Denis repeated, resetting his meter before proceeding in the stilted manner of adolescent public speakers throughout history.

"But today I also would like to look back, back on our four years at Buffalo Grove High School, looking back not with anger, but with no regrets. No regrets for what we wanted to do but did not, for what we wanted to say but could not. And so I say here today the one thing I wish I had said, the one thing I know I will regret if I never say."

Denis paused for dramatic effect. Somebody coughed. Denis extended the pause to rebuild his dramatic effect.

He blinked the sweat off his eyelashes.

Then he said:

"I love you, Beth Cooper."

DENIS COULD THINK of no logical reason why he should not attempt to mate with Beth Cooper.

There were no laws explicitly against it.

They were of the same species, and had complementary sex organs, most likely, based on extensive mental modeling Denis had done.

They had both grown up here in the Midwest, only 3.26 miles apart, and could therefore be assumed to share important cultural values. They both drank Snapple Diet Lime Green Tea, though Denis had begun doing so only recently.

And while Beth was popular and good-looking—Most Popular and Best Looking, according to a survey of 513 Buffalo Grove High School seniors—Denis did have the Biggest Brain and wasn't repulsive, exactly. It was said that he had a giant head, but this was an optical illusion. His head was only slightly larger than average; it was the smallness of his body that made it appear colossal. He had the right number of facial features, in roughly the right arrangement, and would eventually grow into his face, his mother predicted. She also said he had beautiful eyes, though in truth, one more than the other. His teeth fit in his mouth now, and he did not have backne.

Denis could imagine any number of scenarios under which his conquest of Beth Cooper would be successful:

if Beth went to an all-girls school in the Swiss Alps, surrounded by mountains, hundreds of miles from any other guys except Denis, son of the maths teacher, and

Beth was failing algebra, for example;

if Denis was a celebrity;

if Denis had a billion dollars;

if Denis was six inches taller, and had muscles.

Any one of those scenarios.

One also had to consider that there were 125 to 200 billion galaxies in the universe, each with 200 billion stars. Using the Drake equation, that meant there were approximately 2 trillion billion planets out there capable of sustaining life; the latest research suggested that one-third of them would develop life and one-ten-millionth would develop intelligent life. That left 1,333,333 intelligent civilizations created across the universe since the beginning of time, surely one of which was intelligent enough to recognize Denis and Beth were meant for one another.

Alternatively, if current string theory was correct, there were a googol googol googol googol googol universes, all stacked up with this one but with different physical properties and, presumably, social customs. In one of these, odds were, Denis Cooverman not only bred with Beth Cooper but was worshipped by ravenous hordes of Beth Coopers. Unfortunately in that universe Denis had crab hands and inadvertently snipped each Beth Cooper to bits as she came ravenously at him.

This was but a small sampling of the thinking that went on in Denis's Biggest Brain prior to Denis's sweaty lips declaring his love for Beth Cooper in front of 3,221 hot, testy people.

For all its obsessive analysis, Denis's Biggest Brain had neglected to consider two relevant facts. Big Brains often have this problem: Albert Einstein was said to be so absentminded that he once brushed his teeth with a power drill. But even Einstein (who, according to geek mythology, bagged Marilyn Monroe) would not have overlooked these facts; even Einstein's brain, pickling in a jar at Princeton, would be able to grasp the infinitudinous import of these two simple facts, which now hung over Denis's huge head like a sword of Damocles—or to the non-honors graduates, like a sick fart.

The two incontrovertible, insurmountable, damn sad facts were these:

Beth Cooper was the head cheerleader;

Denis Cooverman was captain of the debate team.

THERE WAS A MOMENTARY DELAY in the reaction to what Denis had just said, because nobody was listening. While the adults contemplated cold beer and college tuition, and the graduates contemplated cold beer and another cold beer, their brains continued routine processing of auditory input, so that when Denis's mother yelped Oh no, they were able to rewind their sensory memory and hear, again:

"I love you, Beth Cooper."

Mrs. Cooverman had been following right along, syllable by syllable, and she knew something was up at syllable ninety-four, when Denis went off the script they had worked so hard on. Her Oh no was the release of tension that had accumulated in the subsequent twenty-nine errant syllables, building suspense for her alone. She did not know who Beth Cooper was, but she knew this was not appropriate for a graduation speech, and probably worse. Mr. Cooverman had been enjoying the speech until his wife yipped.

The bleachers echoed with confused murmurs, while down on the floor the graduating class retroactively grasped the tragic nature of what had transpired, and laughed. Dr. Henneman had been calculating how many dirty, dirty toilets required Mr. Wrona's lavish attention and had not noticed anything wrong until she heard the laughs; they seemed genuine, and that was not right.

Everyone who knew who Beth Cooper was—the entire class and several hundred adults—craned their necks to stare at her. She was near the end of the third row, next to an empty chair, the seat Denis himself was to return to once he was done humiliating her.

He wasn't done.

"I have loved you, Beth Cooper," Denis went on, his eyes clinging to his notes, "since I first sat behind you in Mrs. Rosa's math class in the seventh grade. I loved you when I sat behind you in Ms. Rosenbaum's Literature and Writing I. I loved you when I sat behind you in Mr. Dunker's algebra and Mr. Weidner's Spanish. I have loved you from behind—"

This got a huge laugh, one Denis should have expected, being a teenager. He also should have anticipated that Dr. Henneman would be looming up behind him, about to put her hand on his shoulder, but he did not and continued at the same measured pace.

"… in biology, history, practical science and Literature of the Oppressed. I loved you but I never told you, because we hardly ever spoke. But now I say it, with no regrets."

DENIS MADE A NOISE, a dry click, as if resetting his throat.

"And so, let us all, too, say the things we have longed to say but our tongues would not."

He had returned to the approved text. His mother exhaled for the first time in more than a hundred syllables. Dr. Henneman decided intervention was no longer worth the effort, and sat back down. Denis also felt better, having disgorged his annoying heart, and so proceeded more confidently, with the well-practiced cadence of a master debater.

"Let us be unafraid," Denis preached, "to admit, I have an eating disorder and I need help."

Fifty-seven female graduates, and six males, glanced around nervously.

"Let us," Denis chanted, "be unafraid to confess, I am so stuck-up because, deep down, I believe I am worthless."

There were at least seven people Denis could have been referring to, and another four so low on the social totem their conceit was meaningless, but the clear consensus was that Denis was talking about Valli Woolly. Valli Woolly acknowledged the stares by baring her teeth, her version of a smile.

"Let us"—cranking now—"be courageous, truly courageous rather than simply mindlessly violent—"

Greg Saloga. He was definitely talking about Greg Saloga. It was so obvious that even Greg Saloga suspected he was being talked about, and this, like most things, made him angry.

"Let us stand up and say, I am sorry for all the poundings, the pink bellies, the purple nurples …"

Denis had received seven, sixteen and dozens, respectively.

"I'm sorry I hurt so many of you. I am cruel and violent because I was unloved as a baby, or I was sexually abused or something."

Greg Saloga's big tomato face ripened as he erupted from his chair. He had not fully formed a plan beyond smash and head when something tugged the sleeve of his gown. He wheeled around, fist in punch mode, and came very close to delivering some mindless violence into the paper-white face of the diversely disabled and tragically sweet Becky Reese.

"Not now," Becky Reese said in a calming wheeze.

Greg Saloga felt stupid. She was right. He could kill the big-head boy later. He grinned at Becky Reese, much like Frankenstein's Monster grinned at that flower girl before the misunderstanding.

"You should sit down," Becky Reese said.

Greg Saloga sat down.

"In your seat," Becky Reese clarified.

DENIS MISSED his own near-death experience. He was busy expressing the regrets of fellow classmates who started malicious, hurtful and totally unfounded rumors (e.g. Christy Zawicky and her scurrilous insinuation that semen had been found in someone's fetal pig from AP biology) or who chose indulgence over excellence (e.g. most of the class but specifically Divya Gupta, Denis's debate partner, who drank an entire bottle of liebfraumilch the night before the downstate debate finals and made out with both guys from the New Trier team, revealing the entire substance of their argument even if she did not recall doing so). And Denis was just getting started, or so he thought.

"And let us not regret," he said, "that we never told even our best friend"—pause, then softer, slower—"I'm gay, dude."

Denis looked right at Rich Munsch, his best friend. This was unnecessary; everyone knew.

Rich Munsch, however, was flabbergasted. He mouthed, somewhat theatrically: I'm not gay!!!

Denis was about to respond when he felt four bony fingers dig under his clavicle.

"Thank you, Denis," Dr. Henneman said, leaning across Denis into the microphone. "A lot to think about."

For a bright kid, Denis was not quick on conversational cues.

"I'm not done," he said.

"You're done." The principal moved decisively to secure the podium, driving Denis aside with her rapier hip.

She heard a splish.

She looked down and discovered she was standing in a puddle.

THE AUDIENCE SPATTERED ITS APPLAUSE as Denis shuffled off the stage.

"As I call your names," Dr. Henneman was saying, "I would appreciate it, and I think everyone would, if you came up and accepted your diploma quickly, with a minimum of drama."

The applause grew.

Denis felt good about the speech. He had let Beth Cooper know how he felt, after all these years, and had made some excellent points about other classmates besides. He wondered what Beth would say to him when he sat down beside her. He had prepared two responses:

"Then we agree"

or

"It's my medication."

Denis suddenly had a scary thought: What if she tries to kiss me? Would he politely demur, deferring such action to later, or would he accept the love offering, to the thunderous applause of his peers?

So Denis did not see the dress shoe that belonged to Dave Bastable's father that Dave Bastable had stuck in his path. Denis tripped, lurched forward, stomped his other foot onto the hem of his gown, dove across his own chair and sailed headlong into Beth Cooper's seat, where, fortunately or unfortunately, she no longer was.

2. THE 10-MINUTE REUNION

YEAH. WE GRADUATED HIGH SCHOOL. HOW … TOTALLY … AMAZING.

ENID COLESLAW

DENIS GRABBED a Diet Vanilla Cherry Lime-Kiwi Coke from the cafeteria table. He forwent the selection of Entenmann's cookies that was also available for graduates and their families, because his stomach hurt. He could not tell whether this was because he was overheated and dehydrated, or because he had not defecated in the week leading up to his speech, or because he had just done either the single greatest or most imbecilic thing he had ever done in his life.

In any case, the Diet Vanilla Cherry Lime-Kiwi Coke didn't help.

As he had every thirty seconds since he arrived, Denis surveyed the cafeteria. Fresh alumni, a few still in caps and gowns, most in caps and jeans, caps and cutoffs, caps and gym trunks, or, in the case of members of Orchesis, caps and orange Danskins, clustered in the same clusters they always had, in almost the exact spots they once ate lunch, even though none of the tables were there. Yet they all talked about how hot it had been in the gym and what they planned to do that evening, which was pretty much the same, only in different clusters.

She was not there.

ON THE REFRESHMENT TABLE a silver cube blasted the platinum thrash rap of Einstein's Brain,

Fuck this shit

Nuff this shit

The song captured the essence of adolescence and expressed it in easy-to-understand language, while simultaneously managing to aggravate adults, no mean feat these days. (Sales of the clean version were poor, however.)

What you can do wit

All this shit

Just fuck it!

Although Denis didn't like thrash rap, he was feeling a little outlawish and this song, he decided, would serve as his own personal theme song, saying in rhyme what he had said in rhetoric. He moved closer to the table to facilitate others in making the connection.

"Oh, dear God," Mr. Bernard said, rushing past Denis and picking up the music box, searching for a way to turn it off, or failing that, destroy it. Mr. Bernard did not like modern music or its devices, his primary qualifications to head the Music Department. He shook the box, but it only seemed to get louder:

Fuckitfuckitfuckitfuckitfuckit

Mr. Bernard started to raise the box over his head.

"Let me, Mr. Bernard," Denis said, taking the cube from his twitching fingers. He pressed a nonexistent button on the metallic surface and the music changed to that Vitamin C song that wouldn't go away. Lulled by the classical string opening, Mr. Bernard wandered away.

He could have at least said Thank you, Denis thought, or Awesome speech.

And so we talked all night

about the rest of our lives

Denis did his reconnaissance. He did not know what he would do if he found her, only that he needed to do it.

Closest to the exit were clumps of parents who hadn't been dissuaded from attending (Denis's own father and mother – who thought his speech was an "interesting choice" but were still "so very proud of him", respectively – seemed only too happy to wait out in the car, where the Sunday New York Times was). Mothers chatted up the teachers, hoping to squeeze out one last compliment about their children, while fathers checked their Treos for weekend business emergencies.

Rich Munsch fidgeted beside his parents as his father interrogated Ms. Rosenbaum, his English teacher.

"I mean," Ed Munsch said, gesturing with his third complimentary Coca-Cola beverage, "is it really worth all that money to send him to college?"

"Everyone should go to college," Ms. Rosenbaum answered.

Ed Munsch chuckled. "Well, not everyone."

BETH COOPER WAS NOWHERE.

Denis began strolling, ostensibly checking things out but also providing an opportunity for the things to check him out. He was prepared to accept the accolades of his peers with good humor and a humble nod he had been practicing.

He stopped at a twenty-foot orange-and-blue banner hanging on the wall. It read "Congrats to BGHS CLASS OF 'O7" and featured a Mighty Bison painted by Marie Snodgrass, who would one day go on to create Po Panda, star of Po Panda Poops and Oops, Po Panda!, two unnecessary children's books. The bison wore a mortarboard and appeared to be drunk. Other graduates stood around the banner, signing their names to heartfelt clichés and smartass remarks.

No one took note of Denis.

Denis pretended to read and appreciate the farewell messages while searching for his name. The only entry that came close was:

I'm Gay, Dude, signed Richard Munsch

Just below this was affixed:

This was Stuart Kramer's "tag"—which he used exclusively in bathroom stalls and on his notebooks— placed there to ensure proper credit for this witticism. Denis was annoyed; that was his line.

Denis considered seeding the banner with a few anonymous hosannas to his awesome speech, just to get the ball rolling, but he was afraid he might get caught, and he didn't have a pen.

WHERE WAS SHE?

Denis was thinking about just leaving, and then he was thinking about just staying, when he felt those familiar authoritarian talons dig into his soft upper flesh.

"Mr. Cooverman." Dr. Henneman had snuck up on him again.

"Oh, Dr. Henneman," Denis said, with hopeful bonhomie. "Or I guess now I should call you Darlene."

"No," Dr. Henneman said. "You should not."

She fixed Denis with the look, the look she had fixed many thousands of times before, but which she had never imagined she would have fixed on this particular boy.

"Mr. Cooverman," she lectured, "I've never known you to do anything so reckless. At all reckless."

And then came the part of the upbraiding familiar to legions of Buffalo Grove High School malefactors, jokers, and stunt-pullers, an interrogatory also familiar to disobedient children and husbands throughout the English-speaking world.

"What," Dr. Henneman inquisited, "what were you thinking?"

DENIS COULD NOT THINK of what he had been thinking. He knew that what he had been thinking had been carefully thought, and would surely satisfy Dr. Henneman. But he was having trouble accessing his brain. Every time he tried going in there, the view of his vast hypertextual data matrix was obscured by one insistent memory. All he could see was the replay of a few minutes in his room a week before, when he decided to go ahead with the speech. It was the image of Rich Munsch bobbing around in front of his face.

"You gotta do it!" Remembered Rich was saying, in full dramatic flower. "It'll be like—"

Rich puckered his lips and scrunched his nose, and began yelling in a nasal and New York-y accent.

"You're out of order! You're out of order! The whole trial is out of order!"

Denis said what he usually said when Rich went into another of his inscrutable celebrity impressions: "What?"

Rich's response, in the standard format: "Al Pacino in … and Justice for All, 1979, Norman Jewison."

Rich bounced up and down a couple of times.

"Unforgettable speech. Like yours is going to be!"

There was nothing there to quench Dr. Henneman, Denis decided. He also concluded that the sociology of alien civilizations and implications of infinite universes might be too esoteric for the discussion at hand. And he probably shouldn't bring up mating. He began composing a creative plausibility, what in debate they referred to as bullshit, when Rich's face came bobbing across his brain again.

"You will never see her again!" Rich declared with awful finality. "Nunca. After graduation she will be gone! Until like maybe the tenth reunion, if you both even live that long."

Rich enjoyed having an audience, even of one, and took a little strut before delivering his next, tragic line.

"And she'll be so very pregnant—baking someone else's DNA—she'll have this big cow grin and she won't even remember who you are!"

"She'll remember me," Denis said. "I sat behind her in almost every class."

"Behind her. Behind her. Be-hind her," Rich incanted, like a poorly written television attorney. "She never saw you."

Rich stepped back for his close-up.

"You don't exist."

This was a persuasive argument. Denis knew what it felt like to not exist, and didn't much care for it. He doubted it would hold much sway with Dr. Henneman, whose existence nobody doubted. He scanned his memory again, for even the slightest scrap of logic behind this monumental blunder, and there was Rich again.

"If you don't do this," Rich said, pausing to imply quotation marks before croaking out of the side of his mouth in a quasi-tough-guy voice:

"You will regret it, maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life."

"What?" Denis said.

"Bogart, dude!"

"I DUNNO," Denis told Dr. Henneman.

Denis had upon his face that sheepish but supercilious grin only found on a teen male in trouble. He had never deployed it before, but Dr. Henneman had certainly seen it, and she was trained to wipe it off. "Not the behavior I expect from someone going to Northwestern University." And then, oh so coolly: "You know, one call from me and you're going to Harper's …"

That smile wiped right off.

"Oh. Don't do that."

Harper Community College, located just five miles away in once lovely Palatine, offered credit courses in:

Computer Information Systems;

Dental Hygiene;

Certified Nursing Assistance;

Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning;

Hospitality Management; and

Food Service.

It was where young lives went to die.

"That would be … unimaginable," Denis said, even as he was extravagantly imagining it. "I, I don't know what I was thinking … I was … I was under an influence!"

The phrase under an influence triggered a series of autonomic responses in Dr. Henneman: check eyes, arms, grades. But wait, this was Denis Cooverman. Valedictorian, debate champion, meek, quiet, perhaps too quiet, socially isolated … She studied Denis for Goth signifiers: pale, check; pasty, perhaps; eyeliner, no; hair, ordinary; piercings, none visible. His gown: there could be any number of semiautomatic weapons or sticks of dynamite under there.

But, c'mon: Denis Cooverman.

If Dr. Henneman had been one of those evil robot principals you keep hearing about, she would have started repeating irresolvable logic conflict as smoke poured from her optical sockets and her head unit would have sparked and then exploded, just like in Mr. Wrona's sweet custodial dreams.

Instead, she bowed her head and whispered, "Drugs?"

"Oh? No," Denis flustered, "not drugs. They're whack," quoting a health education video that could use some updating. "No, by influence, I meant my thinking process was influenced, negatively impacted, by which I mean … Rich Munsch."

Dr. Henneman smiled. This would be perfect for her blog, The Uncertainty Principal, the twelfth most popular high school principal blog in the state.

"You really shouldn't be taking romantic advice from Richard Munsch," she said.

Denis—and this will be a recurring theme—didn't know that now would be a good time to shut up.

"But he was right," Denis insisted. "I had to do something. I would have been forgotten. Not even. I'm not there." Denis pointed to his head, and because he was Denis, he pointed precisely to his hippocampus. "She has no memory of me. No dendritic spines in her cortex that whisper: Denis."

(Denis knew that dendritic spines did not whisper, but he could be poetic, too, in his own way.)

"So I had to," Denis continued his pleading. "To stimulate dendrite growth. I mean"—and this is where he thought he had her—"Dr. Henneman, haven't you ever been in love?"

Dr. Henneman had been in love, and was in love, with her husband, Mr. Dr. Henneman, who was standing not more than fifteen feet away but remained invisible to all of her students because it required them to acknowledge that she had feelings and plumbing. The plaintiveness of Denis's cry, however, rekindled in Dr. Henneman the heartache of Paul Burgie, the brown-eyed demon who took her to second base (then above-the-waist petting and not a Rainbow Party) and reported back to the other seventh-grade boys that Dr. Henneman's nipples were "weird"—as if he had a representative sample!

Dr. Henneman caught herself crossing her arms tightly across her chest, as she had through junior high. Such silly, everlasting pain. She answered Denis with something approaching empathy.

"There's another Beth Cooper out there," she told him. "One just for you. The world is full of Beth Coopers."

Dr. Henneman began to walk away, already filing Denis under students, former and composing additional summer projects for Mr. Wrona. The grooves between these floor tiles could use a good tooth-picking …

"Dr. Henneman?"

"Yes, Mr. Cooverman?"

"You won't call Northwestern."

Dr. Henneman chuckled. "As if I have any actual power," she confessed, as she often did to graduates. "Denis, with your SAT scores, you'd practically have to kill someone to not get in."

ALONE AGAIN, Denis decided to assume a cool pose against the wall, in case anyone chose to reference him while discussing his now infamous speech. It was a pretty good pose: casual yet defiant. But no one was talking about his speech; few even remembered it. At the end of the ceremony it had flown out of their heads like trigonometry, gone forever.

Denis canvassed the room, a cruel smile playing across his lips, he thought.

Rich's father was at the snack table, filling paper napkins with cookie remains. Rich was performing for his mother and Ms. Rosenbaum, both laughing despite obviously having no idea what he was doing. Miles Paterini and Pete Couvier, the junior ushers, were acting like they were already seniors, scoping out where their lunch table would be, temporarily forgetting how unpopular they were. And there was Stephen Gammel guzzling a Coca-Mocha, the horrible new carbonated coffee beverage, and Lysa Detrick showing off the chin she got for graduation, and:

There she was.

BETH COOPER WAS less than thirty feet away. Twenty-seven floor tiles. She was chatting with Cammy Alcott and Treece Kilmer, fellow varsity cheerleaders and Table Six lunchers. Chatting about him, Denis suspected. Remarkably, he was about to be correct.

Cammy, who had a preternatural sense for when she was being stared at, noticed Denis first. Denis jerked his face to the side—universal body language for Yes, I was staring at you—while maintaining his casual yet defiant pose against the wall. It made him look like a male underwear model, except not. Out of the corner of his rapidly darting eye Denis saw Cammy point. Treece, and then Beth, turned in his direction.

Denis considered yawning to underscore his indifference to the attention, but he was afraid a scream might come out, undermining the effect.

Cammy made a short remark, with either a slight smile or a slight frown. Treece whinnied like a frightened mare, a thing she did in situations where other people laughed.

Beth Cooper began walking toward Denis.