Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Iceland is a country where stories are as important as history. When Vikings settled the island, they brought their tales with them. Every rock, hot spring and waterfall seems to have its own story. Cruel man-eating trolls rub shoulders with beautiful elves, whose homes are hidden from mortal view. Vengeful ghosts envy the living, seeking to drag lost loves into their graves – or they may simply demand a pinch of your snuff. Some of the stories in this collection are classic Icelandic tales, while others are completely new to English translation. Hjörleifur has always been deeply interested in the rich lore of his island. His grandparents provided a second home in his upbringing and taught him much about the past through their own way of life. Hjörleifur is dedicated to breathing fresh life into the stories he loves.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 258

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

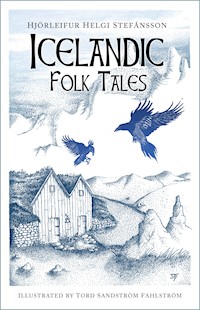

Cover illustrations: © Tord Sandström Fahlström

Illustrated by Tord Sandström Fahlström

‘Ethnic’ icons by Evgeni Moryakov, from thenounproject.com.

First published 2020

The History Press

97 St George’s Place,

Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire,

GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Hjörleifur Helgi Stefánsson, 2020

The right of Hjörleifur Helgi Stefánsson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 .

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9631 0

Typesetting and origination by Typo•glyphix, Burton-on-Trent

Printed and bound by TJ International Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

The Snuffbox

Of Ghosts

Herding Mice

The Troll-wife and the Reverend

The Demon on the Beam

The Skeleton

Seven on Land, Seven in Sea

The Ghost’s Cap

Of Trolls

Gilitrutt

Þórðarhöfði

Of Hidden Folk

The Leg Bone

Egill

A Father of Eighteen

The Fearless Boy

Blackarse Hookride

A Few Odd Men in the East

Crossroads

Mother Dear

Búkolla

The Scythe

In Need

The Hallowing of Látrabjarg

The Laughing Merman

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To sit down and write a handful of one’s favourite tales is a wondrous task. Too much coffee and the river view out of our living room window in the midst of winter creates just the right atmosphere to lure out my ancestors, whether they be people, trolls, ghosts or what have you. It happens to be the same view I had growing up with my parents, Ragnheiður and Stefán. My father rebuilt and added to the house built by my mother’s grandfather to make room for all of us, and my mother grew up on the same farm as me and my siblings and probably did every single awful thing herself that we then later got told off for. I know for a fact that she used to take the milk from the farm on the 1954 International Harvester D217 to meet the collecting lorry, and when out of view she would take it up to sixth gear and full speed. She got caught when she tipped it over one day and probably got a word in her ear, as we say. Is it any wonder us kids grew up to become such hooligans? One of the things I see out of the window, just a stone’s throw away, is Ánabrekka, the house of my late grandparents, Ása and Jóhannes. As I was growing up I spent just as much time on their farm as I did on ours, which is not strange at all considering the two are roughly a kilometre apart. To grow up with one’s grandparents is a true privilege and mine were incredible people. They were born in the old time, in the old country, and they gave me, in my upbringing, a glimpse of another way of thinking and living. Their focus was on people and tradition, they were incredibly hard working and they loved unconditionally. Being very different, they each gave me their own lesson on the past. To their memory I dedicate this first collection of mine.

Amma was a tough lady. She was born in a house of turf and stone and knew hardship. She also knew toil and loss from a very young age and maybe that was somewhat reflected in the way she lived her life. To some, she seemed rough and distant and perhaps she was, but a hard shell is needed for a life that can be cold as a raging snowstorm. Underneath was the open and warm heart of an artist, one who could make anything grow in her garden and one who created the best and beautiful garments to keep her children warm and safe and I got to be one of them. Travelling was her passion and as a grown woman she saw faraway lands, with Asia being the love of her life. She taught me to do my tasks well and question authority, and she taught me to always be myself – I might have lost that fellow at some point but she set me straight with what she had given me to work with. She made me promise I would never become a politician. She was wise and I miss her.

Afi saw our ancestors in a beam of light and made sure I knew them well, he was third generation on our farmland and was very proud of that fact. He believed the land should be worked, a farmer by nature and nurture who tended his animals well and spoke to himself all day long. I even heard a row one morning as he drank his coffee alone in his study. That must have been about something very important. He recited poetry day in and day out and was the most knowledgeable person I have ever known. He was a brilliant angler who knew his river like the back of his hand and was a friend of the salmon. His horses were grey and tall and he was never happier then when he rode through the highlands of the west gathering sheep with his friends and fellow farmers and a flask in his pocket. He gave me my love of tales and the land that they grew from; some of the first stories I remember reading came from books he either gave me or made sure I read. He was a true scholar and I miss him.

Living on a farm with a river running past it, horses to ride in the stables, all sorts of trucks and tractors at hand, a loving family and brilliant storytellers all around are the perfect surroundings to create oneself. Stories are born and shared every day and need to be told in order for them to exist. My parents are without a doubt the best storytellers I have heard and that is saying something, as I am lucky enough to be friends with some of the very best. It was not until I met my brother of lore, Tom Muir of Orkney, that I knew there was such a thing as a storyteller. He has taught me what little I know about delivering a story; I proudly hold the title ‘Pet Viking’ and I do not think there are many others who do. Without him it is quite possible that no one would sit through my ramblings or read my gibberish. Lawrence Tulloch had a great impact on me, a wonderful man and a master storyteller, I miss him dearly and his books are an inspiration for me to write. Jerker Fahlström, my beloved sea ghost brother who teaches me about Scandinavian lore and my boys to fight with a sword, is another master at the trade, and so is Ruth Kirkpatrick, who puts some sort of magic in her tales of ancestry and hidden beings. Dr Donald Smith took a chance years ago and put an Icelandic kid on his stage with some of the best performers in the world and then, he did it again! My siblings, my friends, my children and my youngsters keep me in practice as they are my audience whenever I am bursting with a story. My dearest Anna has patience and makes everything possible. I love you. Those are the people who make me who I am today and for that I am thankful.

THE SNUFFBOX

A while back, in fact quite a long while back when the people of Iceland lived under turf scattered about like sheep grazing, there lived a man by the name of Jón. He lived in an area of Iceland named Snæfellsnes, a windswept peninsula that reaches far out into the Atlantic Ocean. The strong waves there hammer the jet-black beaches and jagged cliffs mercilessly, shaping the land and the people who have lived there for generations. In days of old the people of Snæfellsnes were hardened, perhaps even rough people, who brought their livelihood from the sea in open boats of eight rowers in all weathers. The sea took its toll though; many were lost to the deep over the centuries, many good men did not return to their families after a rough dance with King Ægir.

Our friend Jón, however, had a different way of making a living. Sure, he had been at sea for years and he had worked all the jobs on the small farms, whose tiny turf houses dotted the slopes along the shores like mounds from the earth. But now a fully grown man, he made his own living. Some years back, he had been the first to arrive at a stranded ship one stormy night and had helped the Dutch fishermen escape their broken up schooner to the safety of a nearby farm. He was as strong as an ox, he was, and courageous like a troll in the mountains, and one by one he brought the sailors through the fierce waves to the shore with the wind howling and screaming and snow whirling from every direction till he finally brought the captain last to safety.

As a gift of gratitude, when the captain and the crew had gathered their strength, they gave him something quite unique, a flintlock shotgun they had managed to salvage from the wreck of their ship along with a huge, wax-sealed trunk full of pellets and powder. This was very much against the law at the time; the Dutch and the French fished the Icelandic waters all around the country and to make sure the local merchants could continue getting rich selling maggoty meal and Brennivín (our oh so lovely and strong local schnaps), the law forbade Icelanders having any dealings with the foreign fishermen. For some reason though, the babies in certain areas round the country began to be born with a darker shade than before, but no one knows how that could have come to be. Our Jón had never been too worried about the authorities and gladly accepted the good gift from the grateful captain, becoming the first man in Snæfellsnes to own a gun.

This led to Jón finding a new and better way to make a living. He travelled on foot from farm to farm with his trusted weapon round his shoulder and shot birds from the cliffs rising from the sea, providing fresh meat for the farmers and their families as well as keeping foxes away from the down-filled nests of the eider duck. For this he accepted butter and meat, money and crafts, skins and favours and everything in between. His reputation grew and he became known for his gun and his courage.

One particularly dreary and foggy night, Jón was making his way from one farm to the next where he had been asked to get rid of a particularly stubborn fox that was eating away all the eggs of the eider. He was walking a very narrow footpath he had walked often before, on his left hand was a sheer drop onto the jagged cliffs and the sea below and on his right stretched a vertical mountainside up to the heavens above. As he made his way, he felt a sudden cold, an eerie and even colder gust of wind than the night was blowing his way and a shudder crawled over his shoulders. Out there in the fog he saw a very big shape taking form in front of him and, thinking of the faraway possibility of an ice bear wandering off the land-locked ice the previous winter, he ran his fingers along the shaft of his gun beside him. On he walked, nowhere to go but onward, and soon saw the shape of a huge man emerging fully from the thick fog. He was briefly relieved, but soon saw that this was no ordinary man. The man in front of him was wearing tattered and oilskin clothes, water seeping from under the sleeves, no shoes to protect mangled, bloody feet. In fact, the man seemed drenched and hurt as if he had just fallen overboard and fought for his life on the shores below. It was at that moment it dawned on Jón what he was facing there on the steep mountainside. Not only was he faced with a ghost, but a sea ghost, the ghost of a man who had drowned at sea and never been laid to the long sleep of the hallowed ground. Those were the fiercest of all ghosts, Jón knew very well from the countless tales he had heard in his upbringing, tales of struggles in dark nights, broken bones and even death.

He prepared himself for a fight, knowing very well that he had but one chance and one chance only to defeat that dark being and get away with his life. Turning back was not an option; no one runs from a ghost, not any more than we run from our fate. The ghost stepped a few paces nearer, the stench of death reaching Jón’s nose and, to Jón’s amazement, and not at all calming in any way, he spoke!

‘Whaaat do you haaave haaanging there?’

The ghost grunted in a deep voice and pointed at Jón’s belt. Jón looked down and saw that the ghost was pointing at a hollowed-out ram’s horn that held the powder for the shotgun. Traditionally such hollowed-out horns were used, and in fact still are, as snuffboxes. This particular horn was so big that Jón had taken to keeping his gunpowder in it rather than his snuff. Thinking so fast and so hard he could hear his own brain cracking, he looked upon the endlessly tall ghost and said, ‘Why, it’s my snuffbox. And this …’ he grabbed his gun from behind his back, ‘this is the tool we use nowadays to get the snuff up our noses. Would you like some snuff?’

The ghost looked sternly at Jón and then replied, ‘Aye, I liked my snuff when I lived and haven’t had some for a hundred years.’

At this, Jón took a step back and poured a generous trickle of powder down the barrel of his gun. He then, turning his back slightly to the curious-looking ghost, grabbed a handful of pellets and ran those down the barrel as well. He now pointed the gun up the ghost’s nostrils and fired. BOOM! The loud bang echoed from the cliffs around them and rang in Jón’s ears as a thick cloud of smoke and fog swallowed the pair of them. Jón stepped back, gazing at the ghost, and heard a strong spit.

Again, he prepared for a fight, as it dawned on him that he had probably made the last mistake of his life, angering a sea ghost in the middle of the night, all alone on a treacherous mountain path. As he watched the thick smoke slowly vanishing he saw the ghost with his face down, loudly spitting out the generous amount of unburst powder and pellets Jón had given him. With a look of utter satisfaction, the ghost beamed at Jón and said, ‘Now that was some proper snuff.’ With that and a crooked, toothless smile on his face, the ghost passed Jón and was swallowed by the darkness.

This was the first and last time Jón was bothered by a ghost, in fact he lived to a ripe old age and luck followed him through all his paths in life. From him comes a strong line of hard-working and intelligent people who have made their fortune in all sorts of manner, now spread around our island in the north. And how, you might wonder, do I know all this to such detail? Well, you see, my grandmother, who was a warm-hearted, clever and strong woman who spoke her mind without nonsense, was born on a small farm called Geirakot in Snæfellsnes. She was, of course, one of Jón’s descendants.

OF GHOSTS

The history of ghosts in Iceland is as long as our own, and our relationship with them is complicated, to say the least. From ghosts of newborns left to die who terrorise the mother to skinless, raging bulls, the entities can be as different as they are many. The long and dark winters gave us endless tales of ghosts of women, men, animals and even the ghosts of still-living people, who bode nothing good for the one who met those or saw them. Ours is a dark country in the winter, to say the least. In the time when ghosts followed our every footstep (who is to say they don’t even still?) we lived scattered around the country in farms and small fishing villages and darkness was thick. Lighting was very minimal, simple lamps with cotton grass wicks burned fish liver oil and gave off more smell than light, as candles were a real luxury. Paraffin lamps were introduced much later and changed the atmosphere of the houses dramatically.

We were born in our homes and we died there, events that now are very much hidden away from us, especially the latter. When a person died in the old country, numerous customs were honoured to make sure the deceased stayed that way. One of them was to wash and clothe the body in linen, another was to have a member of the household watch over the body, and yet another one was not to carry the body out the main door, which in some cases meant that a hole had to be torn in a wall of turf and stone, in order to get them to the grave. These habits, however, were not always sufficient, since the fear of ghosts was embedded in us. A common greeting, when a knock was heard upon a door, or someone seen in the dark was, ‘Be you living or dead?’

People travelled heaths and mountain roads in dark and dreary weather and got lost and died frequently, an event we simply call ‘to remain outside’. These were often the less fortunate, the poor, the drifters, single mothers and the handicapped. And indeed many of those who perished on their way between farms or over a mountain road in the dead of winter remained outside, remained as ghosts, who terrorised the living, bound to the place where they froze to death, alone or even with a toddler in their arms.

It is therefore, perhaps, no wonder that ghosts are embedded in our culture and lore. When my mother first visited my father’s stomping grounds, he led her around his small village and told her a ghost story at every turn. She looked at him with a smile and said something the likes of ‘the way you tell it, one might think the whole village was cramped with ghosts, my dear,’ and, with a look of surprise, my father replied, ‘Well, what you have to understand is that it is.’ Another classic setting for a haunting is, of course, the graveyard, which has given us many tales of struggles in the dead of night, churches full of corpses and young women being lured into open graves. A family graveyard sits next to our farmhouse and has been in use for generations now, however, the graves in there remain firmly closed and calm.

As one might expect, graveyards and ghosts connect strongly with the practice of magic. Dark, indeed, very dark things are connected with the dead and the dying, such as the famous ‘nábrækur’ or necropants. They are, in fact, not that hard to create, should you be interested. All you have to do is to make a deal with a man for his corpse, upon his death. You will then dig him up, after the funeral, and flay him from the waist down and immediately put on the newly created pants. They will then heal on to your flesh. You will then place a coin, stolen from a poor widow, in the scrotum of the pants and that will attract more coins. That scrotum will never be empty and you become rich. Make sure, however, that you have found someone to inherit the pants before you die, or you will go barking mad to your death.

Another thing that might come in handy one day is to have your own ghost. Simply do as follows. Find a fresh grave and walk around it counterclockwise, round and round and round. Recite specific, awful poetry (travel to Iceland and do your research) as you increase your speed and intensity. A hand should now emerge from the topsoil, followed by an arm, a shoulder, a head, etc. Once you have summoned the corpse out of the grave you have to attack it with all your might. And you have to win. If you lose, you will be dragged into the grave to spend eternity next to someone you do not even know, or worse, someone you do not particularly like. Assuming that you have won the fight, and have the ghost pinned down on the grave, all you have to do now is to lick and drink the mucus and blood foam around its mouth, and you have yourself a ghost. Use wisely.

HERDING MICE

Straumfjörður is a magical place. It is a fjord in west Iceland with yellow sandy beaches and hundreds of skerries (small, rocky islands) in the waters, some visible, others lurking just below the surface at high tide. It is home to seals and seabirds in their thousands, incredible nature and good people. Those skerries have claimed a hefty toll through the ages as Straumfjörður was settled a long time ago and those who have lived there have both rowed and sailed in all weathers as a part of their daily life and survival. Very good fishing grounds are outside of the fjord and trout swim between the skerries in spring. The land way to the farmstead is long and very boggy, and on top of that flooded during high tide, as the farm sits on an island. This remarkable place was a merchant site for the rural area of Mýrar from the seventeenth century, with big vessels from Denmark making port in a strait formed by an island just off the coast. Ruins of great houses line the beach along the strait to this day and tell the often grim story of the relationship between humble farm folk and the wealthy and sometimes ruthless merchant class. A grand villa was built there in the nineteenth century to house a store and the merchant’s family, but was taken apart and moved to serve as a rectory when the trade moved to the town of Borgarnes.

Long before any of that, there lived a fine woman in Straumfjörður by the name of Halla. Not much is known about her beginnings, in fact they have always been somewhat shrouded in mystery. Some say Halla was the sister of a well-known lady of deep knowledge, Elín, the witch of Elínarhöfði. It was whispered that the sisters had gained their knowledge by attending a school that taught more than the average one, but was extremely difficult to locate. Some say it is in the middle of the Black Forest in what is now Germany, while others claim that it is in Lapland, where all the most powerful magic in the world stems from. It was believed that in order to gain access to the school the pupils had to choose between themselves one to stay behind each year and serve the master of the school for eternity. The two sisters were not the only ones famous for attending that school, for so also had Sæmundur the wise, long before them, but that is a different story altogether. No one knows anything about this school for certain and should you like to attend it you will have to do your own research. What we do know is that Halla lived in Straumfjörður and was both wealthy and wise. She was much respected in the area and was known for her generosity and kindness, but she could be as hard as the skerries themselves if she got angry or felt she was being mistreated.

Halla had many people working on her farm, both family and workers. She had people fishing and she had people farming, and her farm was both a big one and a prosperous one. As was the custom of the time, the produce of the farm was delivered to the nearest merchant, who in return sold Halla items and food imported and not available by other means. The closest one to her at the time was some two days ride away, in Snæfellsnes, and he was a cheap and petty fellow. A poor farmer and a good friend of Halla had recently brought the merchant some very fine products, such as top-quality wadmal, thick and warm fabric woven from the wool of his sheep. The merchant had taken all of the excellent fabric and then made up a big debt that the farmer was supposed to be in, which was far from the truth. The poor man had to ride home with nothing and came to Halla in his despair to plead to her those wrong doings. ‘It seems we will need to teach him a lesson,’ she said, ‘but for now I can help you out with what you need. If you want to help me in return, you can join my workers who are about to start swinging the scythes. When you are done here, I will send two men with you to help gather your own hay.’

The incredibly lush hay fields on the island and in the wetlands on shore were thick and tall and ready to be cut and dried. Her friend happily agreed to the deal, as it was a very generous offer indeed. He paired with four others and they prepared to leave to begin the cutting. ‘Now, listen to me gentlemen,’ spoke Halla before handing them each a scythe, two tents and provisions.

‘You are to cut down the whole ness out by Greystone. You are to cut from morning till night and be done in four days’ time. Each night, as you stop cutting, you are to place the scythes on the stone and head for your tents and your scythes will await you sharpened in the morning. None of you is to look at the scythes before dawn, nor into the edge of the blade or you will have to deal with me!’ With that she sent them off to work.

When the men started cutting they were astonished at how sharp the scythes were. They sliced the thickest sedge like the blade was glowing and the sedge made of butter. They stayed that way from the first cut of the morning till the last stroke of the evening and the men made sure to do what Halla had ordered. That is, until the youngest in the pack had had enough. His curiosity burned and gnawed him all day long, and on the morning of the third day, as he was picking up his scythe, he looked into the edge of it. He let out a yelp of disgust and fright as he realised that the blade of his scythe was a man’s rib, loosely tied to the wooden shaft. Immediately, the other scythes lost their form and revealed the ribs and it became clear that not much cutting would be done with these strange tools.

That same day Halla had been pondering her friend’s troubles with the merchant. It was a foul thing he had done and not for the first time either. He had even cheated Halla herself and talked down her quality products every time she brought him her goods to sell. She, however, had an idea on to how to bring that man to his senses. She decided to consult with her sister, Ásta, who was wise and sharp as the scythes in her men’s hands. Halla had a special place on the highest point of the cliff that faced the open waters outside her house. Whenever she needed her sister’s advice or simply wanted to chat with her, she sat herself down on the edge of the cliff and said softly, ‘Can you talk, sister dear?’ Her sister had a place not unlike Halla’s on her farm and would reply immediately, were she not too busy. The two sisters could thus enjoy a conversation across the bay of Faxaflói, and often did, even though it was a two-day crossing on a ship with full sails. Ásta replied that day and they spoke for a long time. They were good friends and Halla always felt like a load had been lifted off her shoulders whenever the two of them had enjoyed a conversation. They agreed on the merchant being taken down a peg as well as Ásta joining her sister to gather the hay being cut. They could feel approaching rain in their joints. They said their goodbyes with love, both looking forward to their meet.

When Halla was just about to head back home she saw one of her workers returning from the ness. ‘Finished already are you? What mighty reapers I have in my service, to finish a four-day cutting in only two?’

The young man looked at the toes of his leather shoes, with his hands clutched together. ‘I know what you did and what you saw, you fool. Go to the smithy and fetch five scythes little man. Do not forget the sharping stone as these are a bit more conventional and you need to do your own sharpening from here on.’

The young man muttered something underneath his breath and turned to the smithy. He did not return to his fellow workers until nightfall and they began the cutting bright and early the next day. The scythes were of good quality and bit fairly well, but needed constant sharpening and bit nothing close to the ones they had before. However, they were strong fellows and used to the job at hand so they finished in two days’ time and returned home.