7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

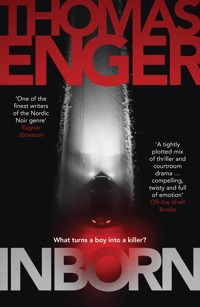

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When a double murder takes place in a Norwegian village high school, a teenager finds himself subject to trial by social media … and in the dock. Bestselling, highly emotive and award-winning Nordic Noir… 'One of the finest writers of the Nordic Noir genre' Ragnar Jónasson 'Satisfyingly tense and dark' Sunday Times 'Spine-chilling and utterly unputdownable' Yrsa Sigurðardóttir –––––––––––––––––––––––– What turns a boy into a killer? When the high school in the small Norwegian village of Fredheim becomes a murder scene, the finger is soon pointed at seventeen-year-old Even. As the investigation closes in, social media is ablaze with accusations, rumours and even threats, and Even finds himself the subject of an online trial as well as being in the dock … for murder? Even pores over his memories of the months leading up to the crime, and it becomes clear that more than one villager was acting suspiciously … and secrets are simmering beneath the calm surface of this close-knit community. As events from the past play tag with the present, he's forced to question everything he thought he knew. Was the death of his father in a car crash a decade earlier really accidental? Has a relationship stirred up something that someone is prepared to kill to protect? It seems that there may be no one that Even can trust. But can we trust him? A taut, moving and chilling thriller, Inborn examines the very nature of evil, and asks the questions: How well do we really know our families? How well do we know ourselves? You loved Quicksand and We Need to Talk about Kevin, now read Inborn –––––––––––––––––––––––– 'A pithy, twisty, challenging tale with a cracking concept … The ending caught in my throat, piercing, then shattering my crime-sleuthing thoughts. Inborn is so very readable, it also provoked and sliced at my feelings, made me stop, made me think, it really is very clever indeed' LoveReading 'If you like your crime smart, dark and morally compelling then you'll absolutely love this book' 17 Degrees Magazine 'Clever plotting and thought-provoking premise. Another feather in Thomas Enger's cap' Crime by the Book 'Thomas Enger's novels are intelligent and emotionally aware and Inborn is no exception … an exciting and thought-provoking novel' New Books Magazine 'One of the most unusual and intense talents in the field' Barry Forshaw, Independent 'MUST HAVE' Sunday Express S Magazine 'Intriguing' Guardian 'Sophisticated and suspenseful' Literary Review 'Full of suspense and heart' Crime Monthly 'Inborn is a small-town murder mystery and courtroom drama with multi-faceted characters and compelling twists that will keep you guessing until the very end' Culture Fly 'A tightly plotted mix of thrillers and courtroom drama … compelling, twisty and full of emotion' Off-the-Shelf Books

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR THOMAS ENGER

‘A deep and complex book. Satisfyingly tense and dark’ Sunday Times Crime Club

‘A tightly plotted mix of thriller and courtroom drama, and a compelling, twisty tale of murder, secrets and lies … Inborn is full of emotion’ Off-the-Shelf Books

‘These are crime novels with a heart – Enger infuses each story with humanity, delivering characters the reader will root for and cry over, sometimes quite literally’ Crime by the Book

‘One of the most unusual and intense talents in the field’ Barry Forshaw, Independent

‘It has real strengths: the careful language, preserved in the fine translation, and its haunted journalist hero … An intriguing series’ Guardian

‘Dark and unsettling … This unforgettable, chilling Norwegian Noir novel has been beautifully translated by Kari Dickson’ Ewa Sherman, European Literature Network

‘For readers who enjoy these Scandinavian imports, this novel is a treat … the dialogue is sharp and snappy, and the characters seem to come alive in this sophisticated and suspenseful tale’ Jessica Mann, Literary Review

‘A fascinating addition to the Scandinavian Noir genre. I look forward to the series unfolding’ Crimesquad

‘Unexpected and surprising … like a fire in the middle of a snowfall’ Panorama

‘The careful revealing of clues, the clever twists, and the development of Henning Juul and the supporting characters make this a very promising start to a new series’ Suspense Magazine

‘Spine-chilling and utterly unputdownable. Thomas Enger has created a masterpiece of intrigue, fast-paced action and suspense that is destined to become a Nordic Noir classic’ Yrsa Sigurðardóttir

‘Thomas Enger is one of the finest writers in the Nordic Noir genre, and this is his very best book yet. Outstanding’ Ragnar Jónasson

‘A gripping narrative that begs comparison to Stieg Larsson’ Bookpage

‘Suspenseful, dark and gritty, this is a must-read’ Booklist

‘From the gritty tension of the plot, to its emotional depths, this is a powerfully compulsive page-turner’ LoveReading

‘Visceral and heartfelt – a gripping deep-dive into the secrets that hold families together and tear them apart’ Crime by the Book

‘The plot is satisfyingly challenging, and the tension is maintained throughout, with characters like Trine revealing their story in instalments, and the swift movement between characters in page-turningly short chapters … there’s also a clever, sleight-of-hand ending’ Promoting Crime

‘Thomas Enger is such a skilled writer that you can only marvel at the intricate plot’ Books, Life and Everything

‘It is cleverly and intricately written, and I am in awe of Enger’s ability to make such complex relationships and background stories come together so seamlessly!’ Portable Magic

‘The author does a fantastic job of creating a dark, twisted story, one soaked in criminality and which left me breathless … If you like a good crime series with a slice of dark menace – I would definitely recommend this!’ Chillers, Killers and Thrillers

‘Enger has weaved a magical plot to once again leave me breathless, the storylines coming together in such a sleek and intelligent way it’s impossible to find a single fault’ Emma the Little Bookworm

‘Fast-paced and so very tense, I was gripped! Dark. Chilling. Emotive’ Ronnie Turner

‘This is a fluffing cracker of a book. As much as I never wanted it to end, I loved every minute of it. Every single page-turn’ Jen Med’s Book Reviews

‘Tense and atmospheric, like all the books I’ve read from this author, the writing is so beautifully immersive and the plotting is taut and terrifyingly emotional’ Liz Loves Books.

‘Enger made this reading journey an exciting one, delivering a killer plot that is nuanced and a masterpiece in thriller writing’ Books are my Cwtches

‘I really loved this book, it is dark, gritty, gripping and had me hooked’ Donna’s Book Blog

‘Dark in nature, with just the right amount of action and emotion. I highly recommend it’ Keeper of Pages

‘Utterly gripping, with a real human aspect. Bravo, Mr Enger. Highly recommended!’ Bibliophile Book Club

‘Dripping with mystery, intrigue and suspense, this atmospheric crime thriller will keep you guessing until the very last page’ Crime Book Junkie

‘Tense and foreboding throughout, especially after the tantalisingly horrific prologue. I was gripped right until the very end – which took me totally by surprise. An outstanding read’ Mrs Blogg’s Books

‘Not just brilliant, it is totally outstanding and worthy of hitting our small screens. My advice is simple: cancel all your plans, ignore the phone and lock yourself away as you will not put this book down. Breath-taking’ The Last Word Book Review

‘The plotting is simply superb. I was riveted and genuinely couldn’t tear myself away. There are so many little threads that come together for the grand finale … Thomas Enger is a talented and clever writer, he manages to hook you in and keep you prisoner until that last word’ Emma’s Bookish Corner

‘A poignantly beautiful book … There can’t be many crime novels that I finish with the tears rolling down my face, but then there aren’t many that are so sensitively and evocatively written. I cannot recommend it highly enough’ Hair Past a Freckle

‘A gritty crime thriller, for those readers who really like to get their teeth into a book, best read over a shorter period to keep on top of the plot, but highly recommended by me … Now to get my hands on Thomas Enger’s other books!’ I Loved Reading This

‘It had a fast-paced, compelling story line that kept me wanting to read on’ What Cathy Read Next

‘Enger combines emotional turmoil, grief and guilt with solid crime scenarios, then infuses his story with a healthy shot of Scandinavian je ne sais quoi’ Cheryl M-M’s Book Blog

‘Brilliant Scandi Noir from an accomplished and exciting writer. What more could you ask for? Highly recommended’ Reflections of a Reader

‘Amazing. Gripping. Thrilling. Cleverly written. Blew me away. That prologue will have you hooked. The whole story had me hooked. Fast-paced, easy to read. You literally won’t want to put this book down’ Gemma’s Book Reviews

‘In Enger’s searing fifth and final novel featuring Oslo investigative reporter Henning Juul, Henning … obsessively pursues the criminals responsible for his son’s death. Meanwhile, malignant figures relentlessly stalk him … Enger seamlessly integrates … individual stories into a larger tale of dirty business and politics. As Henning approaches the end of his painful journey, he longs for the certainty that he has touched someone’s life. His excruciating ordeal will touch the heart of every reader’ Publishers Weekly

Inborn

Thomas Enger

Contents

Publisher’s note:

Inborn is based on Thomas Enger’s YA thriller, Killerinstinkt, translated from the Norwegian by Kari Dickson. The new book contains a complete update and rewrite by the author in English.

PROLOGUE

THE NIGHT OF

Before he made the mistake of opening the door, Johannes Eklund was thinking about the show. He thought about the cheers and the admiring looks the girls had given him, the beers he was going to drink once he caught up with everyone at the opening-night party. The sex, God willing, he was going to get.

In those minutes that passed before he stepped through the doorway and stared in disbelief at what he saw in front of him, Johannes’ mind had been filled with dreams. High on the praise that the night’s performance had received, his eyes had been firmly fixed on the future, on private jets and sold-out concerts, on a way of life he had yearned for every single day since his father introduced him to Stone Temple Pilots and the glamour of rock ‘n’ roll some four years ago.

Right before his throat made that anxious little noise, Johannes wasn’t giving the slightest thought to the fact that he had school tomorrow, nor that he was due to hand in an essay on social economics later this week. School was no longer going to be important to him. Tonight’s show had only made that even more evident.

But then his presence was noticed, and he stood there watching for a few seconds, trying to comprehend what was going on in front of him. Then the stench of urine, sweat and metal rose to his nostrils and made him forget all about the distant future and the very recent past. He couldn’t even process what he was seeing. All he could think was that he wasn’t supposed to be there. That he had to get out.

Now.

His shoes, still wet from the rain, slipped on the floor as Johannes started to run, but he managed to stay on his feet and pick up some speed. The sound of boots, hard against the floor behind him, made him force his legs to move even faster. Heart racing and lungs screaming, he reached the end of the corridor. As he was about to open the door that led to the staircase, he turned and caught a glimpse of the person speeding towards him, eyes so dark it made Johannes tremble and whimper.

He grabbed at the door and ran through. He was about to descend the staircase, when he felt a powerful hand on his shoulder. He turned and raised his hands as if to protect himself, whispering a plea that died on his lips as intense pain jolted through his jaw, paralysing the rest of the muscles in his face. His feet lost touch with the ground, and as the back of his skull made contact with the top of the staircase, it felt and sounded as if something in his head had smashed into a thousand pieces.

He didn’t pass out, but part of him wished that he had. He tried to get up, but something connected with his upper body and pushed him forcefully further down the stairs. Unable to break his fall, he landed on his back and shoulder. Then he toppled down the stairs and came to rest at the bottom.

He couldn’t move.

Couldn’t think, at least not at first. He wanted to scream for help, and he managed to cover his face with his arm, but it was pulled sharply aside. He squinted up at the person above him. Only then did Johannes fully understand how much trouble he was in.

His thoughts turned towards his family and his friends, to the songs he had yet not written, songs that would never be loved, and the tears began to roll down his cheeks. As he felt blow after blow raining down on his face, feeling the numbness travel from his head to the rest of his body, Johannes’ mind drifted away from what was happening to him. He thought about all the fun he had planned. The dreams that would never come true. And as the white lights above him started to fade, he thought of the taste of a girl’s lips. The feel of her body. And when Johannes Eklund could no longer feel a single thing, he could not help but wonder what on earth he’d walked in on, and why the hell he had to die.

1

NOW

‘Nervous?’

The court officer at Romerike District Court looks at me with a tentative smile. She’s been sitting next to me for fifteen minutes, but this is the first time I have noticed that her teeth are yellow. I stop picking at my sweaty fingers, and nod.

‘First trial?’ she asks.

Her breath smells of stale coffee and old cigarettes. I nod again.

‘Hell of a case,’ she says with a sigh. It seems like she’s talking to herself now.

I think about the hours ahead of me. Everything I need to relive and remember. Everything I will be asked, everything I need to talk about, in front of everybody. I remind myself to stick to my story. There are details the court and the judges – and the whole of Norway – don’t need to hear.

The door in front of me opens. A man in uniform gestures for me to get up and follow him. I take a deep breath and stand up. I look at the male officer and wonder for a brief second what he thinks of the case, what he thinks of me. For months the newspapers and the TV stations have been reporting on what happened in Fredheim last October. But I can’t tell one way or the other what he thinks. His look is just dead serious.

I straighten my trouser legs, button my jacket and pull down my slightly too-short shirt sleeves. I wonder whether anyone is going to believe me. They have to, I tell myself. They simply have to.

The uniformed man leads me through a wide door into a big room. Just like on TV, a sea of faces turns towards me. There’s a sudden silence, then it gives way to whispering. I try to focus on the stand ahead of me, grateful that I still have about twenty feet to walk before I get there. The sound of my own footsteps gives me something to concentrate on.

My mother is here. I can see from her face that she’s having a hard time. I wonder how much she’s had to drink and if she’s brought a flask with her.

When I reach the witness box, I turn and look at the crowd of people in front of me. I don’t really see anyone in particular, just heads. Every seat in the room seems to be taken. People are even standing at the back. As I begin to focus, I see reporters, laptop screens. Familiar faces from Fredheim. Some of my friends, schoolmates – if I can even call them that anymore. Police Chief Inspector Yngve Mork is here, as is Mari’s mother. I can’t see her dad, though, nor any of Johannes’ parents.

The lawyer for the prosecution is a slim, small lady. She looks slightly masculine in her tight dark-blue suit. I don’t really know anything about her, except that her name is Håkonsen. She takes a sip of water from the glass in front of her and looks at me with inquisitive eyes. As if she’s wondering whether she will be able to break me, or something.

She wishes me a good morning, before politely asking me to state my name and address – for the record.

‘My name is Even Tollefsen,’ I whisper.

‘Please speak up’, the judge says.

I move closer to the microphone and cough slightly before repeating myself. I try to give the two other judges an apologetic smile. I don’t get one in return. I tell them our address – Granholtveien 4 – and that we live in Fredheim.

‘It’s about an hour’s drive from Oslo.’

I don’t know why I said that. They know where Fredheim is. After what happened in October, everybody does.

‘How old are you, Even?’ the prosecutor continues.

‘I’m seventeen.’

I can’t keep my voice steady, so I try to take a deep breath. My chest hurts.

Now the prosecutor wants me to talk about my family. I catch a glimpse of my mother again. She’s slumped down in her seat. It looks as if she’s trying to hide.

‘My father died in a car crash when I was seven.’ I say, my mouth feeling dry. ‘So I was basically brought up by my uncle Imo.’

‘Imo?’

‘Sorry. Ivar Morten,’ I say. ‘Everyone in Fredheim calls him Imo.’

There is a slight chuckle in the room. It relaxes me a little.

‘But you lived with your mother?’

‘Yes.’

‘And your brother Tobias.’

‘Correct.’

‘OK. Would you say that you had a happy childhood?’

I look at my mother again, before staring at the table in front of me for a few seconds. ‘Like I told you, my father died when I was very young. So no, I wouldn’t necessarily say that I was a happy kid. Depends on how you look at it, I guess.’

‘Are there other ways to look at it?’ the prosecutor wants to know. I move about in my chair.

‘Obviously, I missed my father,’ I say. ‘And we moved a couple of times, back and forth, and my mother … she wasn’t doing very well, to be honest, but I managed to make a lot of friends. So I guess in some ways I was a happy kid. It helped that I played football.’

‘Alright, Even,’ Ms Håkonsen says. ‘Do you mind if I call you Even?’

‘Not at all.’

‘OK. Thank you. Let’s move on a little bit.’

She gets up and starts to walk up and down in front of me, as if she’s thinking deeply about something. Suddenly she stops and says, ‘Mari Lindgren.’

Ms Håkonsen stares at me for a few seconds. ‘Could you please tell the court what kind of relationship you had with her?’

Just hearing her name makes my whole body ache. I take a deep breath again. ‘Mari Lindgren was my girlfriend,’ I say, my voice tiny and sad.

‘For how long?’

‘About five months.’

The courtroom is so silent even the slightest of movements can be heard.

‘But she wasn’t your girlfriend on Monday the 17th of October last year, was she?’

I don’t answer straight away. I just wait a few seconds then shake my head.

Ms Håkonsen looks at me sternly. ‘For the sake of court proceedings,’ she says, ‘you have to answer the question aloud.’

‘Um, no,’ I reply. ‘She wasn’t.’

‘Why wasn’t she?’ Ms Håkonsen asks. ‘What happened?’

‘She … broke up with me.’

‘And why did she do that?’ Ms Håkonsen sounds as if she is already getting tired of my answers.

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know?’

‘Well, I didn’t. At the time.’

‘You mean you didn’t know on the night of 17th October?’

I lift my head slightly, searching for Mari’s mother. My eyes lock on hers. She instantly looks away.

‘Correct,’ I reply.

‘But you know now.’

‘I do.’

Ms Håkonsen looks at me for a few moments.

‘I understand why you don’t want to talk about that, but I’m afraid we will have to go into the specifics or your break-up a little bit later. Just so you know.’

‘OK,’ I say and cough into my palm.

‘Good. When did she break up with you?’

I can feel the sweat starting to form between my shoulder blades. I hope it won’t show on my face as well.

‘A couple of days before…’ I stop for a few beats.

‘A couple of days before the 17th of October?’

I nod, angry at myself for not being calmer and cooler about this. Ms Håkonsen is about to reprimand me again, but I quickly answer:

‘Yes.’

‘OK. Alright. Let’s talk about the morning after. The morning of October the 18th. Tell us what happened.’

2

THEN

Yngve Mork had never spoken to God. He hadn’t even thought that he could, or should; but the previous night, at a quarter past two, he had sat up in his bed, lifted his gaze towards the ceiling and addressed Him directly for the first time in all his sixty-three years.

He had asked if she was OK now, if she had found peace. He asked if she was still angry with him and if He might allow him to see her one more time – for real. But his words had been quietly absorbed by the faded yellow plaster of the ceiling. They hadn’t even been spat back at him like a mocking echo.

Some mornings he woke up with the lingering remnants of a dream in his mind, and with the sudden, panicked thought that she might have come to see him during the night; that she had given him some sign he had missed or already forgotten – a wave or a kiss. He was always hoping that she really was trying to reach out to him, trying to tell him something – trying to say that she had found it in her heart to forgive him.

Today, though, Yngve’s mobile phone alarm startled him just before seven. It had been yet another one of those almost-sleepless nights. He had turned over again towards the empty side of the bed, only to see that there weren’t any fresh dents in the linen, no marks on the pillow from the pen she had used while trying to solve a newspaper crossword. He had sniffed, searching for a hint of her perfume, the smell that had been beside him for forty-one years; but all he could register was his own odour, a smell that seemed even older and more useless now that he no longer had anyone to share it with.

All the other women in Åse’s family had grown old. It was the men who found death at an early age – and under the strangest circumstances. A clumsy bicycle accident or a tumble down a ladder when trying to clear leaves from a gutter. A piece of meat that got stuck in a throat during a celebratory dinner. The women could be sick for years, but somehow they seemed to recover.

So why couldn’t Åse do the same?

Another question Yngve had asked The Ceiling.

He got up and went downstairs, and sat at his breakfast table with a buttered slice of bread and a generous helping of Danish liverpaste in front of him. He had coffee and a glass of orange juice as well, but there were no sounds to keep him company other than the ones he made himself: the flipping of a newspaper page, a knife quietly placed on the side of the plate. A quick sniff to get rid of an itch just underneath the tip of his nose. He didn’t want the radio on in case he interrupted her hummings in the bathroom, her steps that might appear in the hallway, the drawers she would open and close whenever she got dressed. Even if she would never do that ever again.

Yngve’s coffee needed some sugar, so he got up and opened the cupboard above the stove. There he stopped and stared at a yellow box of tea he had bought for her two and a half weeks before she died. It was still wrapped in plastic.

Could you put the kettle on, please, Yngve?

Her distant voice made him sob. But before he was sucked into yet another typhoon of grief, the phone rang. He looked at the number and saw that it was being redirected from the 113 service. He would have to take it – he was on call. But first he grabbed the kitchen sink with both hands and steadied himself for a moment. Then he answered, giving his full name and rank.

At first he didn’t hear anything but breathing. Then came a rush of words. He had to ask the person on the other end to repeat them – twice. ‘He’s dead,’ the voice finally managed to say. ‘He’s just lying there. He’s … there’s blood everywhere.’

The voice, Yngve now realised, belonged to Tic-Tac, the janitor at Fredheim High School.

‘OK,’ Yngve said. ‘Don’t touch anything, just go to the main entrance and stay there. Don’t let anyone in. I’m on my way.’

Yngve hung up and took a deep breath. Glanced over at the breakfast table. The one plate. The one glass.

He was on his way, he’d said.

On his way where?

That you have to figure out for yourself, Åse had said to him one night when they were talking about the future she would no longer be a part of. But I want you to move on, Yngve. I don’t want you to forget me, but I want you to continue with your life. Can you do that for me?

He closed the cupboard without looking at the tea bags again and put on his leather uniform coat. He was about to step out into the rain, when she came in through the doorway, almost startling him.

‘Oh, hey,’ he muttered. He hadn’t even heard her coming. Even now, when she looked sleepy, her skin pale and dry, he was struck by her incredible beauty. He always was, especially when she had no make-up on. Not a single raindrop seemed to have landed on her completely hairless head.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I have to go; I don’t have time to clear the breakfast table.’

She said, with her eyes, that it was OK.

‘I’m sorry,’ he repeated, for a lot more than the fact that he had to leave. He looked out of the open door and said: ‘God, it’s really raining.’

He heard her ask where he was off to, what was going on.

‘I don’t know yet,’ Yngve said. ‘But it doesn’t sound good.’

Yngve parked as close to the school entrance as possible. Two girls and a boy were standing outside the door as he approached, eager to get in. They stared at him, intrigued.

The janitor opened the door for him.

‘I did as you told me to,’ Tic-Tac said, his voice shaking, a spasm seeming to twist his face. ‘I’ve been standing here the whole time.’

‘Can we come in, too?’ one of the girls behind Yngve asked. ’It’s so cold.’

‘No,’ he said with a firm voice.

‘What’s going on?’ the boy asked. ‘What’s happened?’

‘We don’t know yet,’ Yngve answered and closed the door. He turned to Tic-Tac. ‘Where is he?’

Tic-Tac pointed to the stairs. They moved along the hall, their wet shoes making squeaking noises on the floor. ‘I didn’t touch anything,’ Tic-Tac stuttered.

From halfway along the passage Yngve could see a leg and a shoe. As they approached the stairs, more and more of the body became visible. Thin legs, blue jeans. Dark-red stripes that seemed to form a neat pattern on the young boy’s skinny fingers. There was blood on his coat, too, and on his other hand, arm. On the stairs, the wall.

Tic-Tac was right, Yngve thought to himself. There really was blood everywhere.

Fredheim was a small place, but Yngve had seen a lot during his tenure as a police officer here. Body parts in ripped-apart cars, corpses that had been rotting away in the forest throughout the winter. He had seen what people looked like after they’d been hanging by a rope from the ceiling for a couple of weeks, images that sometimes haunted him on nights when sleep was hard to find.

But this…

The young boy’s face looked like mince. Skin, blood, muscle. Teeth coloured red.

‘It’s Johannes Eklund,’ Tic-Tac said.

‘How can you tell?’ Yngve asked without taking his eyes off the kid.

‘His coat,’ the janitor said. ‘The logo on his chest.’

Yngve spotted it now, sewn onto a pocket: an old plane in the middle of a turn, an ‘S’ and a ‘C’ on each wing.

‘He was the singer of Sopwith Camel,’ Tic-Tac added. ‘He had a stunning voice. You should have seen him last night. A genuine star.’

‘There was a show here yesterday?’

‘Yeah. In the auditorium. Opening night of the annual school theatre show.’

‘When?’

‘Between eight and ten, roughly.’

‘And you were here? You watched the show?’

Yngve turned to look at the janitor, who was scratching his left palm.

‘I watched a little bit of it, yes.’

‘What time did you leave?’

He seemed to be thinking for a moment. ‘I don’t know, long before the show was over. I knew I had an early start today.’

‘So you didn’t lock the doors before you left?’

Tic-Tac shook his head violently. ‘There was no need. The doors lock automatically at eleven. Everyone should have made their way out by then.’

‘Evidently, not everyone did, though.’

The janitor didn’t reply.

‘What happens if someone does stay behind after eleven? Can they still get out?’

Tic-Tac hesitated for a moment, now scratching his left temple. ‘They can, of course, but it triggers the alarm, and if the alarm goes off, the security company will be here in minutes. We have two surveillance cameras on the outside wall as well, pointing towards the entrance, so it’s easy to find whoever’s responsible. And they get the bill.’

’The alarm didn’t go off last night, did it?’

‘No.’

‘So if people want to avoid triggering the alarm … can they?’

Again, the janitor appeared to be thinking. ’I guess people will find a way out of here, if they need to. But it’s never really been an issue. People know the rules. Plus, there’s a reminder ten minutes before eleven, a ding-dong sound that’s played for about thirty seconds over the school’s PA system. That always makes people hurry out.’

Yngve considered this for a moment while turning back to look at Johannes Eklund. Not even the persistent banging on the entrance door could persuade him to wrench his gaze away from what used to be the face of a good-looking young man. Yngve had seen pictures of Johannes in the Fredheim Chronicle.

‘Can you see who it is?’ he asked Tic-Tac. He coughed to clear his voice. ‘Let them in if they’re police or from the ambulance service. No one else can enter.’

Tic-Tac moved quickly, his keys rattling on the chain that hung from his jeans. Yngve took a few more steps towards the staircase, being careful where he placed his feet. He squatted down beside the body and examined it more closely. Now he could clearly see lacerations on the left side of the boy’s forehead. He quickly scanned the stairs and hall for a potential murder weapon. Nothing.

The sounds of footsteps at the entrance made Yngve stand up. It was his colleagues from Fredheim police station Vibeke Hanstveit and Therese Kyrkjebø. He had called them, on his way to the school. Normally Hanstveit, officially in charge of every investigation they conducted, would stay away from the crime scene, but the second he’d told her that a young boy might have been killed, she’d headed for her car. Kyrkjebø did the same.

Yngve met them with his arms raised, telling them to brace themselves. Then turned and led them over to the stairs.

Hanstveit put a hand in front of her mouth. Kyrkjebø made a gasping sound. None of them spoke for a few seconds.

Finally, Hanstveit cleared her throat and said: ‘Have you called the forensic team yet?’

‘No, I was just about to,’ Yngve replied.

‘Let me take care of that,’ Hanstveit said. ‘You have other things to tend to right now.’

Without waiting for his reply Hanstveit pulled her phone from her coat pocket and walked a few steps away. Kyrkjebø edged past Yngve to the foot of the staircase. Drips fell from her clothes onto the floor in front of her, so she moved back slightly. Then she just stood there. And looked. Only her eyelids moved. Her face seemed to lose more colour by the second.

She swallowed, then swallowed again. ‘He must have been here all night’, she said in a quiet voice. She wiped her wet face. Touched her neck. Then squeezed the tip of her nose between her thumb and index finger.

Yngve placed a hand on her shoulder. He could feel the muscles tighten under her uniform jacket.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘It’s just that…’

‘I know,’ Yngve said quietly.

Kyrkjebø blinked. A tear squeezed its way out. Yngve looked up to the ceiling and sent another thought to God. An angry one.

‘Let’s search the rest of the school,’ he said. ‘For all we know the killer could still be here.’

3

Yngve asked to borrow Tic-Tac’s keys, then instructed him to go and guard the main entrance door. Once the janitor was in position, Vibeke Hanstveit agreed to stay where she was so she could both monitor the crime scene and keep an eye on potential movements by the door.

Yngve and Therese then began to search the ground floor, checking every schoolroom, washroom, closet or trash bin. But they didn’t find anyone – or anything that might have been used to kill Johannes Eklund.

‘We need to find out when they last cleaned this place,’ Yngve said.

‘I’ll get right on it,’ Therese said, her voice still only a whisper.

Yngve looked at her. Twenty-eight years old, one child at home, another one on the way – although this was hard to tell, except maybe in the slightly more rounded cheeks. He noticed how hard she was trying to steel herself, to think professionally and clearly, something she normally managed easily. Sights this brutal, though, especially with young kids involved, were impossible to prepare for. Pictures in books, however real, never came close to the real thing. Some things you just had to experience the hard way.

Vibeke Hanstveit was still on the phone when Yngve and Therese got back to the staircase. Just as they arrived, a tall, grey, bearded man emerged from the staffroom at the other end of the hallway. Yngve recognised him immediately. It was the school’s principal, Tor-Olav Brakstad.

‘How the hell did he get in?’ Therese asked.

Yngve started to walk towards the principal, raising a hand in the air to get him to stop.

‘There’s been a crime here,’ Yngve said to him. ’We have to shut down the whole school.’

‘What?’ Brakstad asked. He had a bewildered look on his face. ‘What’s happened?’

‘I can’t go into any details just yet,’ Yngve replied. ‘We only got here a few minutes ago. How did you get in?’

‘The janitor’s door,’ Brakstad explained and nodded in its direction. ‘On the other side of the school.’

‘The janitor has his own entrance?’ Yngve couldn’t quite believe what he was hearing.

‘It’s right next to his parking space,’ Brakstad said. ‘For me it’s a short cut. But what…?’

‘I’m sorry, but you have to leave. No one but police or medical examiners can be here right now.’

‘But…’

Brakstad tried to look past Yngve. The police officer made himself as big as he could in order to block the view. ‘Have you seen or heard anyone else in the building – since you arrived, I mean?’

Brakstad shook his head. ‘But…’ he started.

‘You can’t be here now,’ Yngve said firmly while glancing out of the windows. More pupils had arrived, and it was impossible for them all to fit under the canopy over the entrance. So they just stood there in the rain, alarms and questions written all over their faces.

‘Can I get my coat first?’ Brakstad asked. ‘It’s freezing out there.’

Yngve looked at the clouds of steam pouring from the students’ mouths, then instantly evaporating. ‘Be quick about it,’ he said.

Brakstad hurried away and returned a minute later. Again he tried to see what was going on at the end of the staircase, but Yngve put a hand on his shoulder and led him towards the exit. Tic-Tac opened the door. The noise from the thunderous rain made Yngve raise his voice: ‘I’ll find you later.’

Brakstad turned and shot him another quizzical look. ‘I’m going to need help,’ Yngve continued. ‘With information, first and foremost. We just have to get a grip on the situation first.’

He then turned to the students: ‘Go home, please. There won’t be any school today.’

‘What’s going on?’ one of the boys nearest the entrance asked.

‘Please, just go home,’ Yngve pleaded. ‘You’re making it harder for us to do our job.’

But neither the boy nor any of the other children made any attempt to leave. Instead they began to throw questions at both Yngve and the principal.

Yngve didn’t reply. He simply closed the door and addressed Tic-Tac: ‘You didn’t tell me about your door.’

‘Hm?’

‘The door on the other side of the school.’

‘Oh. That.’

He laughed nervously. ‘I didn’t think to mention that.’

‘Really. Is it connected to the alarm system?’

‘Um, no.’

‘So … when I asked you about other exit possibilities, you didn’t think to mention a door you probably use on a daily basis?’

‘I’m the only one with a key,’ he said in a quiet voice.

‘Apparently the principal has one, too.’

‘Oh yes, that’s true. I forgot about that.’

‘You forgot about that too,’ Yngve said with a sigh. ‘Is there anything else you’ve forgotten to tell me, Tic-Tac?’

He thought about that for a few seconds. ‘I left my door open last night.’

‘You did?’

‘Yes, Imo asked me to.’

‘Imo. You mean Ivar Morten Tollefsen?’

‘That’s right. He said there might be a lot to do after the show, and he didn’t want to trigger the alarm when he left. You know, standing ovations, people to talk to afterwards. The local press, even. I said it was OK, as long as he didn’t spread the word. Imo is a good man. I’ve known him for twenty-odd years. I trust him.’

‘Why didn’t you just give him your key?’

‘Like I said, I knew I had an early start. I would be needing my own key to get in, as the doors don’t open before seven-thirty a.m.’

One of the kids outside cupped his face and tried to look in. Steam from his breath hit the glass.

‘Just … stay here for now,’ Yngve said. ‘Guard the door. I’ll get someone to take your place in a little while. We need to talk some more later.’

‘OK.’

Back by the staircase Yngve stopped in front of Vibeke Hanstveit, just as she was finishing her phone call.

‘Can you ask some of the nearby districts to spare us some hands?’ he asked. ‘We probably have to conduct hundreds of interviews over the next few days.’

‘I’ll see what I can do,’ Hanstveit replied.

‘Good. Thanks. As many as we can get.’

Hansveit was already dialling.

Yngve turned to Therese. ‘We have to talk to whoever was responsible for ticket sales to the show here last night. We need to find out exactly how many people were present.’

Therese was squatting in front of Johannes Eklund’s body, but didn’t seem to be looking at anything specific. Yngve took a few steps closer.

‘OK,’ she finally said in a thin voice, without looking up at Yngve.

He waited a few seconds. Then said, ‘Are you OK?’

Therese got up and nodded, carefully at first, then with more and more force, as if trying to convince herself. She mindlessly stroked her belly, avoiding his gaze.

‘Let’s have a look upstairs,’ Yngve said. ‘There might be traces on the staircase, and our shoes are still wet. So be careful where you put your feet.’

Therese nodded again.

They slowly ascended the staircase, staying as close to the bannister as they could. The steps and walls were spotted with drops of blood.

‘Look.’ Therese pointed to the door at the end of the staircase, the small, red drop right next to the door handle.

‘He probably walked this way afterwards,’ she whispered. Yngve removed his coat and slowly pushed the door inwards with his elbow, making sure he didn’t touch the blood. He held the door open so Therese could enter, then found the light switch on the other side of the door. One by one the fluorescent lights in the corridor lit up.

It was empty.

They checked the classrooms and washrooms, all locked or empty. They reached the auditorium. The stage at the front was covered with a thick, dark-green carpet. In front of it, red plastic chairs were lined up in rows. Without saying anything, Yngve pointed to a door further in on the right.

It was open.

They approached it slowly and carefully, but their footsteps broadcast their every move. Yngve could now make out the sign on the door. It said MUSIC. He pointed to the handle and stopped in front of it. More blood. A congealed spot.

He walked through the doorway.

And stopped again.

‘Oh dear God,’ Therese said, as she came up beside him.

On the floor in front of them was another dead body.

4

I woke abruptly, not sure what time it was or even if it was day or night. My head was spinning, pounding. I tried to remember when I had gone to bed, but I had trouble recalling what I’d done the previous night.

Then it all came back to me.

I’d been thinking about her, about what I’d like to do to her when I saw her. Who the hell breaks up with anyone by text and then goes into hiding for two days?

Just the thought of Mari made my heart start to race, but not in a good way. Not excited. A strange sensation spread through my whole body, an uneasiness I really couldn’t explain. I wasn’t nauseous. I wasn’t nervous, either. I just felt … weird. Like my gut was doing somersaults or something.

I got out of bed and checked the time. It was still early. I had time for a shower before breakfast. Neither the hot water nor a couple of knekkebrød with butter and goat’s cheese helped, though. It’s just the lack of sleep, I said to myself. That, or the crap food you always stuff down your throat.

I went into the hall and started to get ready for school. I looked at myself in the mirror and wondered, yet again, what on earth I’d done to her. Had I said something? Done something? Was it something I should have done? Or did she simply not like me anymore?

I ran my fingers through my hair and rubbed in some wax. Stepped back and looked at myself. I thought I looked pretty good. Six feet tall now. Not much fat on my body. I was pretty smart, too. Wouldn’t have any trouble finding another girl. Trouble was, I didn’t want another girl. I wanted her.

In the mirror I saw movement behind me. My younger brother, Tobias, was padding down the stairs, hands in his pockets, joggers almost falling off. He’d changed so much over the past six months. He was almost as tall as me now, and I could tell that he had put on some muscle. He’d let his hair grow longer, too, and he sometimes put it in a man bun, like I did. Usually, though, he just stuffed it underneath a baseball cap, like he didn’t care. He didn’t care about much, to be honest, except maybe his online games.

Tobias was not an easy person to get close to. Never had been. More than once I’d wondered whether he ever talked to anyone outside school. He was a speak-when-spoken-to kind of kid. It didn’t help that his face was always covered in acne, dark and red.

‘You don’t have much time if you’re going to get to school,’ I said, gesturing at the clock with my head.

Tobias stopped at the bottom of the stairs but said nothing.

I pulled on my waterproof trousers. It was pouring down outside – solid, hard rain.

‘Well, get a move on then,’ I said, trying not to sound like a nag. ‘School starts in half an hour.’

Tobias didn’t answer. Just shuffled off into the kitchen. ‘There’s no milk left, by the way,’ I called after him. ‘Don’t think there’s any corn-flakes either. I can get some later.’

‘Awesome,’ he said, then closed the door behind him. For some stupid reason he had started to use that word a lot lately. Awesome. Like he meant the opposite. I wondered if he had any intention of going to school at all. Perhaps you should wait, I asked myself, just to make sure. Mum wouldn’t be around to check, or care, even. She was at Knut’s.

Then I thought about Mari again. I wanted to see if I could catch her before the bell, so I could finally get her to talk to me. I decided to let Tobias be.

It was a young girl, probably no more than sixteen years old. She was lying on her back, eyes wide open. The skin on her face was pale white, lips light blue. She had dark-brown eyes and a small crack in her upper lip. The pink winter coat she was wearing had been opened, as if someone had tried to undress her.

‘I know who she is,’ Therese said almost soundlessly. ‘She came by the station the other day. Her name’s Mari Lindgren.’

Yngve turned to Therese. ‘Why did she come to see you?’

‘Not me specifically. She just came by, asking questions about an old car accident. I think she was working on a story for the school newspaper.’

Yngve turned to face the dead girl again. Her hair was neatly spread out across the floor. As if she was posing for a picture.

‘She has dark spots on her neck’, Therese said. ‘Perhaps someone strangled her.’

Yngve wasn’t listening. For a brief moment it was Åse lying there, staring up at him. Just as she had one of the last times he had visited her at the hospital.

I can’t do it, Åse.

You have to. For me. Please.

‘This is going to get nasty.’

‘Hm?’

Therese pointed at the dead girl.

‘Two murders in a school in this tiny little town? People will go crazy with fear unless we catch the bastard quickly.’

Therese’s lips continued to move, but Yngve couldn’t make out the words they formed. He lifted his gaze from Therese’s face; because that’s where he saw her, standing against the wall. Åse was looking at him with those shiny, bright eyes that always made him feel like the most important person in the whole world. He blinked a few times. Then she was gone.

5

‘Shall we check out the rest of the school?’ Therese asked.

‘Sorry?’

‘There are a few more classrooms we haven’t checked yet. On either side of the stage.’ She made a nodding motion with her head.

‘Oh,’ Yngve said. ‘Yes, of course.’

She looked at him for a few seconds. ‘Are you alright?’ she asked.

‘I’m fine,’ he said. ‘Let’s go.’

They went down the corridor that led back from the right-hand side of the stage. The floor was covered in footprints and smudges of dirt. They walked past an empty can of Coca-Cola, a box of snus. Therese grabbed the handle of the first door they came to. Locked. Yngve tried the next one. Same. Therese tried the handle of the door at the end of the corridor.

It was open.

She looked at Yngve but didn’t open the door right away, as if afraid of what might be found on the other side. Yngve came up behind her, about to say ‘Let me enter first’, but Therese was already on her way inside.

She flicked on the light switch.

There was no one there, only four desks filled with office supplies, stationery, pens, coffee mugs. On a huge whiteboard were written the numbers 4/16, with a few keywords underneath: EDITORIAL; SCHOOL PLAY; EVEN TOLLEFSEN; CHRISTMAS PARTY; FEATURE STORY: PRINCIPAL BRAKSTAD.

‘This must be where they make the school newspaper,’ Therese said. ‘I wonder if one of these desks is Mari Lindgren’s.’

A tapping sound made Yngve look around. One of the windows was open; it was gently knocking against the window frame. Therese pointed her finger towards yet another dark spot on the wall in the corner.

More blood.

‘This must be where the killer left the building,’ she whispered and pointed through the window. ‘He probably wouldn’t dare leave through the main door downstairs.’

‘Yeah, too big a risk,’ Yngve said. ‘Too many possible witnesses. Plus there are surveillance cameras down there as well.’

He pulled his dry shirt sleeve from under his coat sleeve and used it to open the window fully. The wind and cold hit him in the face. Checking there were no marks, he carefully placed his hands on the windowsill then stuck his head out and looked upwards. He had to blink fast as the raindrops were hitting him hard. Right next to the window he noticed a drainpipe that reached all the way up to the gutter.

He came back inside and said, ‘We have to get up there and see. It’s easier to get away unseen on the other side of the school. I think there’s a fire escape ladder up there, too.’

‘Maybe we’ll be lucky,’ Therese said. ‘Maybe he got stuck on something or lost something that will make it easier to identify him.’

‘Maybe,’ Yngve said, and began to climb onto the windowsill.

Therese stopped him. ‘What the hell are you doing?’

‘I’m going up.’

‘No, you’re not.’

‘Yes, I am. It will take ages before the forensic teams can do this. They aren’t even here yet. And the school is huge – several thousand square metres at least. The teams have to comb through every inch of it. We don’t have time to wait. It’s pouring outside – we might lose vital evidence.’

He could tell that Therese was still unsure.

‘I’ll just take a quick look around and see if I can find anything before it gets flushed away,’ he said.

She held back another protest as Yngve once more stuck his head out into the cold. The rain trickled down his neck and shoulders as he peered out. He looked down. A fifteen feet drop, at least. Below more and more students had arrived. The media was there too. Like cattle they had gathered around the perimeter tape.

‘Be careful,’ Therese pleaded behind him.

Yngve pushed himself up onto the sill then leaned out and grabbed the black drainpipe with his hand, making sure he had a firm grip. He carefully placed his boot on a small bracket that held the drainpipe in place and made sure it held his weight. Then he kicked himself out with his left foot and clung on to the drainpipe with both hands. The freezing rain made them cold in an instant.

Yngve pulled himself up a few inches and put his left boot on another bracket. As he was about to push himself up, the sole of his boot slipped, and for a split second Yngve thought he was going to fall to the ground. He managed to cling on, his knuckles going white. He could feel how heavy he had become, how little exercise he had been doing since Åse became ill.

Therese called to him from the inside. ‘Come back in!’ she shouted. ‘Please.’

Yngve looked down and blinked. The rain made his hands slippery. But he still had a firm grip on the drainpipe, and there were only six or seven more feet to the edge of the roof. He placed his boot on the bracket again but this time pushed his toes into it as hard as he could. And slowly, inch by inch, he was able to pull himself upwards. Soon he was able to reach the gutter. He stretched out and got a good grip of it. Then he slung one leg onto the roof, and with a final effort made it up safely.

Vapour was pouring out of his mouth. What the hell are you doing? You’re sixty-three years old. Are you trying to give yourself a heart attack?

‘I’m breathing,’ he said out loud. ‘Trying to, at least.’

No one could hear him up here in the noisy rain. Wet and cold, Yngve glanced around. Below one of the ambulances still had its blue lights on. They danced on the school walls, on the trees around the building. Yngve knew that his uniform jacket had reflective strips that shone in the dark, that he probably looked like a skeleton silhouette up here. But then it occurred to him that not just anyone could do what he’d just done. Certainly, it wasn’t a fine display of strength and agility, but you needed a bit of both to be able to get up on a roof like that.

The roof itself was almost flat, which made moving around easy. The surface was covered with gravel. In the dim morning light Yngve could see it was littered with pine needles and dead branches, brought here by the wind.

He paused for a moment, trying to think like the killer. He or she must have been preoccupied with getting away without being detected.

Taking small, careful steps, Yngve made it over to the other side of the roof. He couldn’t see any houses nearby that had windows facing the school; there were only trees, an open field of grass, then another cluster of trees. Behind that was a kindergarten, which Yngve knew hadn’t been open last night. The chances of anyone having seen anything, at least on this side of the school, were slim.

Yngve walked as close to the gutter as he dared, trying to wipe away some of the water that was streaming down his face. At the far end of the roof there was a fire-escape ladder. He walked over to it, knelt down, leaned over the edge and stared at the ground below. A white van was parked close to the wall. The janitor’s vehicle, probably. There