Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

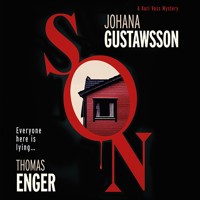

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

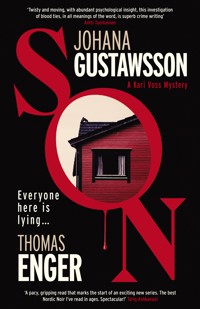

- Serie: The Kari Voss Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Psychologist and expert on body language and memory, Kari Voss investigates the murder of two teenaged girls in the small Norwegian town of Son, as suspicion is cast on multiple suspects. A mesmerisingly dark, twisty start to a nerve-shattering new series by two of the world's finest crime writers… `A breathtaking thriller with a complex plot and twist to die for. Simply brilliant´ Express `Gustawsson and Enger deliver a one-two punch that's a stone-cold knockout´ Alexandra Sokoloff & Craig Robertson `A pacy, gripping read that marks the start of an exciting new series. The best Nordic noir I've read in ages. Spectacular!´ Tariq Ashkanani `The disturbing consequences of this are fully explored in a haunting tale that concludes with a sickening double twist. Son is everything a crime novel should be — and more´ Sunday Times _______________________ Everyone here is lying… Expert on body language and memory, and consultant to the Oslo Police, psychologist Kari Voss sleepwalks through her days, and, by night, continues the devastating search for her young son, who disappeared on his birthday, seven years earlier. Still grieving for her dead husband, and trying to pull together the pieces of her life, she is thrust into a shocking local investigation, when two teenage girls are violently murdered in a family summer home in the nearby village of Son. When a friend of the victims is charged with the barbaric killings, it seems the case is closed, but Kari is not convinced. Using her skills and working on instinct, she conducts her own enquiries, leading her to multiple suspects, including people who knew the dead girls well… With the help of Chief Constable Ramona Norum, she discovers that no one – including the victims – are what they seem. And that there is a dark secret at the heart of Son village that could have implications not just for her own son's disappearance, but Kari's own life, too… For fans of Harlan Coben, Lars Kepler, Jo Nesbo and Jorn Lier Horst … and The Mentalist _______________________ `Written by one of France's leading crime writers and one of Norway's best-selling authors, the story introduces a truly original character that we will hear much more of´ Daily Mail `Two prime exponents of international crime fiction … this is Franco-Nordic Noir delivered with total authority´ Financial Times `Twisty and moving, with abundant psychological insight, this investigation of blood ties, in all meanings of the word, is superb crime-writing´ Antti Tuomainen `Blown away by this cracking thriller and I was already loving it before they hit me with THAT ending. Bravo!´ Trevor Wood `Utterly gripping and brilliantly layered … kept me hooked from start to the twisty finish – Nordic Noir as it should be´ Lilja Sigurðardóttir `This is the perfect thriller´ Michael Wood `A potent reminder of just how powerful crime fiction can be. An absorbing, original and deeply affecting novel that grips with a fierceness and masterfully drags the reader into the darkest places. Brilliant in all senses of the word´ Rob Parker `A body-language expert with a grief of her own, a devastated community full of secrets, and a final sentence that leaves you reeling´ Sam Holland

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 546

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THANK YOU FOR DOWNLOADING THIS ORENDA BOOKS EBOOK!

Join our mailing list now, to get exclusive deals, special offers, subscriber-only content, recommended reads, updates on new releases, giveaways, and so much more!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Click the link again so that we can send you details of what you like to read.

Thanks for reading!TEAM ORENDA

PRAISE FOR SON

‘A pacy, gripping read that marks the start of an exciting new series. The best Nordic Noir I’ve read in ages. Spectacular!’ Tariq Ashkanani

‘When two excellent writers collaborate you know it’s going to be good, but SON surpassed expectations. Great premise, great characters and, simply put, a great book’ Yrsa Sigurðardóttir

‘SON is a potent reminder of just how powerful crime fiction can be. An absorbing, original and deeply affecting novel that grips with a fierceness and drags the reader, masterfully, into the darkest places. Brilliant in all senses of the word’ Rob Parker

‘Gustawsson and Enger deliver a one-two punch that’s a stonecold knockout’ Alexandra Sokoloff & Craig Robertson

‘This is the perfect thriller’ Michael Wood

‘I absolutely loved it. A body-language expert with a grief of her own, a devastated community full of secrets, and a final sentence that leaves you reeling. Bravo!’ Sam Holland

‘Blown away by this cracking thriller from Thomas Enger and Johana Gustawsson. I was already loving it before they hit me with THAT ending. Bravo!’ Trevor Wood

‘SON had me gripped from the first page to the last. A perfect slice of Scandi Noir, and that ending! More, please!’ Lisa Hall

‘It has everything I look for in a crime novel. Clever, intriguing, atmospheric’ Michael J. Malone

‘Twisty and moving, with abundant psychological insight, this investigation of blood ties, in all meanings of the word, is superb crime writing’ Antti Tuomainen iii

‘Utterly gripping and brilliantly layered, SON kept me hooked from start to the twisty finish – Nordic Noir as it should be’ Lilja Sigurðardóttir

‘A great macabre thriller’ Trip Fiction

‘A thrilling, intricately woven slice of Nordic Noir, and it has a delicious sting in the tail that leaves me wanting more, much more. I had a brilliant time with SON and I would happily recommend it to lovers of crime thrillers and police procedurals, and Nordic Noir of course’ From Belgium with Book Love

‘This is an exceptional police procedural that is twisty and full of tension, the storyline had me obsessing over whom the perpetrator was even while I wasn’t reading, and that is the mark of a bookbanger’ Judefire33

‘Wow. Literally devoured this in a day. Brilliant main protagonist and a twisty tale, unpredictable, clever, beautifully written’ LizLovesBooks

‘Such an addictive, page-turning mystery that I had to put my Kindle in another room, so I wasn’t constantly tempted!’ Stephanie Bramwell-Lawes

‘Five enormous stars for SON by Johana Gustawsson and Thomas Enger. A beautifully crafted thriller with an ending I didn’t see coming. It is certainly not one to be missed. Really hoping for much more from these two talented authors’ Sally Boocock, Bookseller

‘What do you get when you mix the female Dexter with the Norwegian answer to Inspector Rebus? Something really, really, REALLY clever and cruel’ Sussi Louise Smithivv

vi

vii

SON

A KARI VOSS NOVEL

Thomas Enger & Johana Gustawsson

viii

ix

‘Memory works like a Wikipedia page: You can go in there and change it. But so can other people.’

(Dr. Elizabeth Loftus, professor in psychology and expert on memory) x

xi

To Karen, the one and only Mrs. Orenda xii

Contents

1

My son is missing.

My boy, my roots, my sky.

I’m standing on my terrace, looking at the clouds – draped in pink in the east, orange in the west, as if they are having a hard time agreeing on which outfit to wear. The sun is slow to set this evening, but the air is already carrying the freshness of night.

A shiver runs through me. I fold my cardigan across my chest. It’s not the cold that makes me tremble, but fear – a fear that knots my throat and twists my stomach.

This morning, when I opened my eyes, I wondered whether today’s summery forecast would turn into one of those treacherous Norwegian June days, when the rays of sunshine only warm the heart. I thought about all the children who would be arriving later for the pool party in honour of my son’s birthday. I thought about all the fruit that needed to be cut for dipping in the chocolate fountain; the candy-floss machine that had to be tested; the tiered cake that sat, finished but wobbly, in the wine cellar. I had closed my eyes for a moment, revisiting the faded memory of my late husband’s smile, imagining how we would have spent this morning celebrating our son’s ninth birthday.

The bay-window door onto the terrace rattles.

I turn around. My father is standing in the doorway, anxiety stiffening his body, freezing his features. It’s clear there’s still no news.

‘Ramona’s here,’ he says.

I get up and go inside, closing the bay window behind me, the stale kitchen air suffocating me in an instant. Dirty glasses and piles of plates, stained with streaks of chocolate and pink sugar, jostle on the kitchen counter like remnants of a past life.

Vetle’s pool party had been a great success. My father and I had 2been running around like headless chickens, probably just as happy as the children who seemed to be communicating solely through shouts of joy and bursts of laughter, playing one game after the other, gigantic doughnut-shaped buoys and water pistols always at the centre of their adventures. As usual, Vetle had teamed up with Eva, Hedda and Jesper, our ‘Fantastic Four’ – as we parents had nicknamed them – our children having been inseparable since their first year of preschool.

Towards the end of the afternoon, the children gathered in the living room, Vetle asking my father – ‘Grandpa Police Chief’ – to show them his service badge and recount his most thrilling stories. Wide-eyed, the young ones had hung on every word, my dad telling them about nerve-wrecking car chases and dramatic arrests.

‘But you mean … you were the one putting cuffs on them?’ Hedda asked, one arm around Vetle’s neck, the other around Eva’s, Jesper sitting on the sofa next to me – as he often was.

‘Yes, sometimes I did.’

‘Wow,’ Eva said, smiling, Jesper laughing with excitement, padding Vetle’s back as if he’d been the one making the arrests. I wondered who was the proudest – my father or my son.

When William Bülow had arrived at 7:00 p.m. to pick up Hedda and Eva to go to some star-studded movie premiere in the city centre, the Fantastic Four were still very much glued together, playing football.

‘You’re alive,’ William teased me. ‘Twenty-odd sugar-infused terrors screaming in your garden. I’m officially in awe.’

‘Thank you,’ I replied with a smile.

‘You must be exhausted.’

‘No, no, I’m okay.’

He laughed. ‘You’d think the world’s leading expert in lie detection would be better at lying.’

‘You’re not the first one to say that.’

We had both laughed.3

‘Kari?’

My father’s voice.

I blink.

I’m still standing in front of the dirty dishes, snatches of the day coming back to me, video clips running through my mind. But with each replay, they become more distorted, so that soon, the only memories I’ll have of today will be these deconstructed and arbitrarily reorganised images, recoloured and twisted out of shape.

‘Come.’

As I follow him down the corridor, my father turns around, glances at me briefly, before striding on authoritatively. The fact that I’m well into my forties hasn’t changed a thing – I’m still his only daughter and he is still my rock. After Vetle’s father died, my dad became my lifeline and the safety net that ensured I didn’t have to choose between my son and my career. History had repeated itself: I grew up without a mother, and my son was making his way through life without a father. But for Vetle, the absence of his father was just some abstract fact, and ‘dad’ was just a concept to him. His ‘Grandpa Police Chief’ had fixed everything.

Police Superintendent Ramona Norum is busy talking to a uniformed police officer when she spots me. The officer responds to her instructions with quick, attentive nods, then Ramona walks over to us.

I first met her eight years ago. I had contacted her after watching a TV interview in which a defence attorney, when asked about his client’s innocence, clearly lied through his teeth. The fact that I turned out to be right was the beginning of a fruitful collaboration, which later developed into a warm friendship that also extended to Ramona’s family – Linnea and their two sets of twins.

Ramona wraps her arms around me in a maternal hug. I don’t have to imagine her pain – the pain of a mother contemplating this nightmare, and surely preferring it to be mine than hers, as any parent would – I can feel it in her body.4

I break away from her, knowing full well that I will collapse completely if I let myself get caught up in the warmth of her embrace.

After Hedda and Eva had left with William, Vetle asked me if he could go over to Jesper’s place.

‘Now?’ I looked at my watch. It was almost 7:30.

‘Pleeease?’ He jumped up and down in front of me, tugging at my cardigan, anticipation glistening in his eyes.

I knew what was going on: Jesper had invited my son to play Fortnite or God knows what video game I would never allow in my house. Jesper’s parents were different. I looked at my son and ran a finger across his sweaty forehead, removing the debris of grass stuck to his harmonious features.

‘One hour,’ I said, instantly regretting it.

‘Hour and a half,’ Vetle replied. ‘It takes a bit of time to get there and back, Mama, even if I take my bike. I’ll be home by nine. Promise.’

I smiled and leaned down to kiss him, my son smelling of chlorine and the summer scent of sunscreen.

‘Okay. Not a second later.’

‘Yay!’

And with that, Vetle and Jesper had set off, as they’d done so many times before. After Vetle had called from Jesper’s house, telling me they’d arrived safely, I sent my father home and worked for a bit, putting off tidying the kitchen and garden.

I was looking forward to Vetle’s return.

Even though it would be late, I wanted to indulge him with another episode of the latest series we were watching together. After all, it would still be his birthday for another couple of hours.

It wasn’t unusual for my son to be a few minutes late, but when he hadn’t return by 9:15, I called Anita Bach-Hansen, Jesper’s mother. She told me that Jesper had taken Vetle half the way back, as he normally did, but that he had been home for a good twenty 5minutes. A ball of anxiety formed in my chest, paralysing me in an instant.

I had then called my dad, who insisted that there was probably a perfectly reasonable explanation why Vetle hadn’t arrived back home yet. Sometimes children just lost track of time or lost their bearings. It happened all the time. The police would wait a while before sending out a search party, he said, even if we called them now. This was different, I told Dad. I could feel it. Vetle knew how important it was to be on time, and he knew the roads and tracks in the Bygdøy woods like the back of his hand. Still, my dad told me to stay put, in case Vetle returned, and to keep my phone with me at all times. I hadn’t argued: my father had been in the police force for more than half his life. But my whole body had been screaming to go out and search for my son.

Strangely, at that instant, Vetle’s birth had come back to me. The midwife telling me to stop pushing. The umbilical cord had wrapped itself around Vetle’s neck, strangling him, and his heart rate had slowed to a dangerous level, so I was waiting to be taken to the operating theatre for an emergency C-section. My whole body was imploring me to push to deliver my son, but the midwife was urging me to fight against nature in order to save him.

An hour had passed and Vetle was still missing. It was then that my father had relented and called in the cavalry.

That was fifty minutes ago.

‘According to Jesper, he and Vetle split ways in Paradisbukta,’ Ramona says. ‘And Jesper went straight back home. He didn’t see anyone lurking around, he said.’

I look at my father. For the first time ever, I can see my rock crumbling. He is bent over, his posture defensive, no longer assertive. My heart starts beating so fast I can’t hear anything else. I can smell Vetle as if I’m nestling my nose in the hollow of his neck. I can feel his wet, unruly strands of hair slipping through my fingers as I comb it. His laughing eyes, provocative, loving, gentle.6

My son.

My precious son.

‘As I was explaining to the boss …’ Ramona’s gaze turns away and settles on my father, her superior. ‘We’re talking to everyone we come across in the woods, but at this hour it won’t be many. We’re knocking on doors close by as well, in case anyone has seen anything out of the ordinary. I’ve called in every available resource we have, and we’re scouring the forest. We’ll continue the search into the night. As you know, the woodland is quite large and full of paths and trails. But we’re lucky: it’s still light for a while, and the temperature isn’t too bad either.’

I shake my head to chase away the terrifying pictures my fear is painting, every single one making me want to vomit.

‘You reacted quickly,’ Ramona continues. ‘Which is very good. He can’t have gone far.’ She clasps my hand between both of hers. ‘Try not to worry, Kari’, Ramona says. ‘We’ll find him. We will find your Vetle.’

2

A few minutes past midnight, they find his bike.

It was sitting at the bottom of a slope no more than a metre away from the fjord, toppled over with a twisted front tyre, its chain detached. They didn’t recover his helmet, but they found traces of blood on some sharp stones nearby, which indicated that someone – most likely my son – had been in some kind of accident. They will test the blood to see if it is a match.

The fact that the accident appears to have happened so close to the shore sends my fear spiralling. Ramona tries to reassure me, saying that there are trees and branches around that would have prevented him from falling into the fjord. But she can’t prevent me from panicking. If he’s not in the water – where the hell is he?

When my phone rings at 8:00 a.m. sharp, the house is a hive 7of activity. Unfamiliar faces hover over computers and monitors, their urgent whispers a constant background hiss. I’m sitting on the living-room sofa, trying to breathe, trying to detach myself from the situation to maintain my calm. I’m failing. Hard.

The display on my phone reads ‘Unknown’.

I see the alarm on Ramona and my father’s faces. The air seems to grow thick, making it harder to breathe.

‘Answer it,’ Ramona says, her voice strained but steady. ‘Could be a concerned neighbour or something, offering to help. Or maybe one of your clients?’

With trembling fingers, I slide my thumb across the display. My ‘Hello?’ comes out as a careful whisper.

‘Put on TV 2.’ The voice on the other end of the line is robotic.

‘What?’ My heart is beating so hard I can feel it pulsing in my throat. ‘Who’s this?’

‘Put on TV 2,’ the voice repeats. ‘We have your son.’

The line goes dead.

I freeze and stare at my father first, then Ramona.

‘Did you … did you hear that?’ I stammer.

Ramona frowns for a second, then snaps her fingers to get the attention of the others in the room. She gives an order to the policeman closest to her, who turns on the TV. He needs my father’s help to find the right channel.

The screen seems bigger than usual. On TV 2, a blonde news anchor wearing a red blazer is finishing a segment. She waits for the prompter to move on to the next item.

Then:

‘Thirty-eight thousand dead. And more on the way. A mix of fear, hope and greed has now produced a horrifying record.’

My heart is pounding in my ears. Which deaths is she talking about?

The news anchor continues:

‘More people have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea than ever before. At least thirty-eight thousand. That’s close to ninety 8a week, almost thirteen per day. Rickety boats that should never have sailed. Unscrupulous smugglers with no regard for life. And desperate people are risking everything …’

I don’t understand. The robotic voice is on a loop in my head. Bile is rising.

We have your son.

Around me, the technicians have started to stir. Silent orders are given, arms are in the air, hands pointing towards something I can’t see. My father is standing next to the coffee table, staring at the TV, his arms crossed. Drops of sweat are beading down my neck and spine. I can feel them under my arms as well. Ramona squats down next to me, placing her hands on my shoulders.

When the news presenter starts talking about Jose Mourinho, the display on my phone lights up again.

‘Unknown’ once more.

Ramona motions for me to wait for a few seconds while her technicians connect a software program to record the call. She gets the thumbs-up. Someone mutes the TV. An unbearable silence settles in the room, punctuated only by the rhythm of my phone ringing.

Ramona picks it up; I can’t bring myself to do it. She activates the speaker.

‘Hello, Kari.’ It’s the same robotic voice.

An involuntary moan escapes from my throat.

‘And hello everyone.’

I look at my dad; he’s listening intently. Whoever this is, they knew that we’d have the police here already, and that they’d be monitoring my phone.

I swallow hard, forcing strength into my voice: ‘This is Kari Voss. Where’s my son?’

The reply comes swiftly: ‘You have received an email.’

The line goes dead, and I’m left with the thundering of my heart in my ears.

I gasp, frozen.9

This isn’t happening, I keep repeating it in my head. My mind is a maelstrom of disbelief. This cannot be happening.

‘Do you have an email app on your phone?’ Ramona asks.

I manage to nod. She grabs my phone again and flips through my apps. A few moments pass, then she says:

‘They’ve sent you a video.’

She takes a few steps away from me. I realise why. My whole body starts shaking. She wants to spare me in case…

I close my eyes, pushing away the end of that train of thought.

My dad comes over and grabs my arm like a claw. I close my eyes again and shake my head, chasing away images all too horrible to grasp.

‘Good news,’ Ramona exclaims. ‘Vetle is OK.’

She walks back to me and squats down once more, placing the phone against a stack of books on the coffee table. She starts the video.

I hiccup as I see my son sitting on a chair in a living room somewhere – it’s impossible to tell where.

He’s alive.

My son is moving.

Breathing.

I put a hand over my mouth, stifling a cry. He’s wearing the same Zlatan Ibrahimović football shirt he had on during his birthday celebrations. There is a large band aid on his left arm. A glass of milk is sitting on the table in front of him.

Behind him, on the wall, a TV is showing TV 2’s news anchor telling the viewers that thirty-eight thousand people have lost their lives trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea.

‘My God,’ my dad says.

The video lasts six seconds.

Ramona plays it four times in a row. The fifth replay is interrupted by another incoming call. Again, the display reads ‘Unknown’. This time, I answer immediately, not waiting for the green light from Ramona.10

‘What do you want?’ I snap, my voice firm, steeled by anger.

‘Five million Norwegian kroner,’ the robotic voice replies. ‘There will be instructions.’

3

Two days later, and the silence is driving me crazy.

Ramona has pulled every police case file I have been involved in over the past eight years, looking for people who might have a reason to target me, for revenge or any other purpose, but she’s found no potential suspects. My father, being the chief of the Oslo police, would, of course, be an obvious candidate if these were ruthless criminals looking for payback, but these people – or this guy – wants money, and for some reason he has chosen me – Vetle, us – as his victims.

It has been two hours and fifty-seven minutes since we wired five million Norwegian kroner into a cryptocurrency account, as per the kidnapper’s instructions. I had to mortgage the house, and my father managed to take out another loan on his home. Despite the short notice, we pulled it off.

But we’ve not heard a thing since. No calls, no messages. No emails. Nothing.

Ramona and her team are glued to their screens round the clock. I don’t want to hear any of the details of what they’re doing. I don’t care about ‘following the money trail’. I don’t care who the guy is either. All I care about is getting my son back, alive.

Time is ticking by with unbearable slowness. It’s as if every second is a rosary bead, every minute a prayer.

And I have started praying. Praying to a God I’ve never believed in, but who gracefully manifested himself the second my son was taken away from me.

My chin falls to my chest. I force my eyelids back open to chase away the terrifying images that keep imposing themselves on my 11inner eye. I hear a panicked ‘Are you OK?’ from my dad, who is sitting opposite me at the kitchen table. I nod a few times, trying to control the venom before it spreads throughout my mind.

Suddenly, one of the police officers shouts:

‘They’ve made contact again. We’ve got coordinates!’

My heart starts beating wildly. I get up from my chair.

‘It’s … not too far from Ytre Enebakk,’ Ramona says, looking closely at the screen. ‘A bit more than half an hour from here.’

‘It’s near a car park,’ the officer adds, pointing at the map. ‘In the woods. According to their instructions, Vetle is waiting for us in a makeshift tree house. Kids build them all the time,’ he adds when I look blankly at him. ‘I used to do it myself.’

‘OK,’ Ramona says. ‘Let’s go.’

4

Ramona gets in behind the wheel. My father is sitting next to her. For some reason I’m in the back, hanging on to the handle above the window with both hands as we speed out of the city.

Soon I will see my son again.

That is all I can think about.

We will go home, I will make him his favourite meal, and tonight I will lie down beside him as he falls asleep, watching over him so that no one will ever take him away from me again. I’m going to stay awake all night watching him breathe and dream.

My son, I say to myself.

My child.

I’m on my way. We’re almost there. I’m coming to get you.

I have no idea where we are or how long we’ve been driving, but all of a sudden, we find ourselves on a small country road surrounded by trees. The satnav tells Ramona to turn left and go further into the woods.12

Stones and twigs crunch and snap underneath the tyres. After a few minutes we arrive at a car park.

‘There must be a pathway here somewhere,’ my dad mutters from the front seat. He is looking at his phone, where he has pinned the GPS coordinates provided by the kidnappers. ‘There.’

Ramona manoeuvres the car towards the far end of the car park. We stop, get out, and start running into the woods down the path my dad has found.

I can barely feel my feet.

‘It shouldn’t be too far,’ my father says.

I’m one stride behind him, searching the woodland floor for traces of my son. ‘Vetle!’ I shout. ‘Are you here? Where are you, Vetle?’

There is no reply.

We continue moving forward. All I can think of is hearing his voice, feeling his skin. Having him nestled in my arms.

‘There!’ my dad shouts as he points to a nearby fir.

I squint and see some planks above us, deep between the dark branches. But I cannot see Vetle. Maybe he is tied up? Gagged? I call his name again. And again. My gut is a knot.

No answer.

I run through the bushes and start to climb the tree, grabbing one branch after the other, panicked now by the quiet, the absence of any movement above. I pull myself up, fingers scraping against the rough bark, and finally reach the tree house. The silence is deafening.

Then – a scream rips through the air.

It takes me a moment to realise that it comes from me.

The tree house is empty.

My son is not there.

5

Seven years later

The impact is immediate, and it hits Eva Eek-Svendsen in a different way to how she had imagined, perhaps even feared, it would. There are no sudden or dramatic changes; no walls dissolving, no floors turning to jelly beneath her feet. The colours stay the same, and she doesn’t experience any psychedelic sensations. She doesn’t melt into another dimension where all shapes, voices and sounds are somehow completely mixed and interchangeable.

That’s what her friends told her it would be like. Jesper included. They had all promised her that it would be awesome and wild and crazy. ‘The only thing you’ll regret is not having tried this before,’ they’d said.

But everything stays almost exactly the same. The only difference being – and it is a rather big one – that she suddenly feels and experiences everything much more strongly. It’s like someone has cranked up the volume on her senses to a hundred. She’s never been this happy. She’s laughing at this and that. Every snack or drink is like an explosion in her mouth. Life is just so very beautiful. How come she hasn’t realised it until now?

Eva also feels a deep, warm love for her parents, and for Hedda. And even for Erik – her brother. They are all so nice. And kind. God, they’re kind. Eva feels an intense need to tell them just how much she loves and appreciates them, how grateful she is to have all of them – every one of them – in her life.

Maybe she should apologise for all the things she has said and done over the years. The ungrateful behaviour, the sometimes-harsh words, especially towards her brother. She reaches for her phone to do this straight away, but she can’t find it. Never mind. She makes a mental note to thank her parents for letting her have the summer house to herself this weekend for the very first time. 14And for allowing her to throw a Halloween party here tomorrow. It is going to be so much fun!

A thought flows by and makes her sad. Before she knows it, the tears are flowing. It’s Samuel – things have turned really sour between them. Should she send him another message? Tell him how much she loves him and misses him, and say that what truly matters, in the greater scheme of things, is them and only them? Can’t they just forget about the whole thing?

Maybe he’s too proud, she thinks. Too upset. Maybe everything is going to stay broken forever.

‘Why are you crying?’ Hedda turns down the volume on the stereo and adjusts the strap of her top.

‘It’s Samuel.’ Eva wipes the tears from her cheeks and chin.

‘Don’t worry,’ Hedda replies. ‘He’ll be here tomorrow. We’ll slip him a little something and he’ll forget about it all.’ She shrugs, like it’s no big deal, and does a pirouette, stretching her hands above her head, singing along to the music, laughing.

Eva smiles watching Hedda dance. This girl everyone wants to be – or be with. No wonder, Eva thinks. She’s gorgeous. Even though it’s late October, Hedda’s skin is glistening like she’s standing in sunlight, not the dark living room. She smells like vanilla and summer.

Just like that, Eva feels great again. The sad thoughts are gone. It’s going to be an incredible night, an amazing weekend. People will talk about this party for ages. She has invited twenty people, as per her parents’ strict instructions, but she’s expecting at least double that. Whatever. It’ll be fine.

A window blows open, the wind rushing through her, making her feel even more alive. Eva walks over to the window, closing her eyes, allowing herself to be enveloped by the cold air, the breeze clinging to her warm skin, making it tingle. When she opens her eyes, the tiny hairs on her arms are standing up like they’re dancing too.

Suddenly, a movement on the lawn makes Eva blink a few 15times. A shadow shifted. Maybe it was just the wind setting the trees in motion. Or the garden lamps – they always create weird silhouettes. That must be it.

There it is again. The movement.

This time Eva is sure.

The shadow looks human. Like a leg moving. Right behind that tree. Is that a hand on the trunk?

‘What is it?’ Hedda asks, coming up behind her.

‘There’s someone out there.’

‘Where?’

Eva points into the darkness, but all she can see are shadows – dark shapes on damp grass. Another gust of wind makes the branches sigh.

‘Nice try,’ Hedda says. ‘But Halloween isn’t until tomorrow. You’ll have to do better than that if you want to scare me.’ She walks towards the kitchen island announcing: ‘We need more.’

Hedda plunges her hand into the plastic bag on the table and comes back to Eva with two small crystals wrapped in paper. Eva takes one of them. Puts it on her tongue. Hedda does the same.

They both swallow.

The taste is bitter, but it will soon pass. A little sip of champagne, a few flakes of potato crisps.

‘Wo-hoo!’ Hedda cranks up the music and throws her hands up as if she’s just scored.

Eva looks out of the window once more. There was someone out there earlier, she’s sure of it.

But it doesn’t matter.

She can feel the high coming already and this time it will even be better.

My God, she thinks, closing her eyes, smiling, the bass echoing through her body as each note travels through her. If she dies now, it will be as the happiest sixteen-year-old in the world.

6

Sitting on the bus, Samuel Gregersen is nervous. The feeling reminds him of those moments before he steps on stage or sits down for a particularly tricky recording session. Checking his cell phone, he sees that the bus will arrive in Son a few minutes late. He tries to distract himself, to disconnect – to meditate, sort of. Be mindful and all that.

The sun hangs high in a cloudless sky, as if summer has suddenly reawakened. Samuel, a lifelong city dweller, finds himself strangely drawn to this countryside – perhaps because of its unfamiliarity. He scans the fields beside the road, half expecting to see a deer or moose, but encounters only an expanse of farmland. The grass, cut down to its roots, lies naked and grey, festering in the relentless sunshine.

This morning, Samuel had wavered about going to Son, even though the plans had been made months ago. But he knows that everyone expects him make an appearance at the party – after, all Samuel is Mr. Halloween himself, and is known for taking matters to the extreme, sometimes even beyond. His friends at school have talked of nothing else recently: how awesome, fun, and scary it is going to be. Yet no one seems to have noticed that Samuel hasn’t been spending any time with Eva and Hedda lately, like he normally would.

During his morning make-up routine, Samuel realised that he couldn’t just cancel, blaming it on some sudden illness. That would only invite all sorts of questions. No, he has to face this head-on. Yet the prospect of seeing the girls again fills him with dread, and that fuels his nervousness.

His mum joined him in the bathroom this morning, curious, as always, about where he’d been the night before and how late he’d come home. Samuel answered as evasively as he could, knowing how concerned she was about how his partying was 17affecting his schoolwork, his future. She has always urged him to apply himself, to reach for the stars. ‘You have everything it takes to become Norway’s next Leif Ove Andsnes,’ she’d tell him over and over. When he protested, she would stop him and say: ‘I just don’t want you to waste your life away, Samuel. If I’d had half the talent you have …’

Samuel knows she’s right. He does have a gift. Since childhood, music has been his language. He remembers hiding, as a young boy, under the dining table during a funeral that was on TV, moved to tears by the sombre music. At the time, he had not realised that it was an inexplicable shame about these feelings that had made him seek shelter. Despite being quite the prodigy already, that experience only intensified his devotion to the piano, discovering that he had a unique connection to it. To Samuel, the piano isn’t just an instrument; it’s a portal, a time machine, a way to tell stories. His fingers paint emotions across the eighty-eight keys, weaving narratives he can’t put into words. It’s like his hands are speaking for him.

Right now, though, Samuel craves normalcy. He wants to party like everyone else his age, to explore life on his own terms. That’s not too much to ask, is it? Julliard or the Royal Academy of Music will still be there when he’s ready for them.

A little after ten, Samuel steps off the bus in Son. Hoisting the bag of props over his shoulder, he starts up the winding road to the Eek-Svendsen summer house. With each step, the knot in his stomach tightens.

In the garden leading to the house, the girls have placed pumpkins here and there, carved to look like ghosts and monsters. In one of the flower beds, a skeleton is feasting on a rag doll. Clever, Samuel thinks. Very Walking Dead.

He notices traces of dirt on the tarmac of the driveway, then scorched rubber marks. Deep tyre tracks cut across the lawn beside him, but they don’t seem to match the black van parked in front of the house. Its side door reads Solsiden Catering and is 18adorned with a sunflower logo, a website address and a phone number.

An eerie silence envelops the house.

Suddenly, heavy footsteps thunder from within. The front door flies open, and a man bursts out, collapsing onto all fours near the garage, retching violently.

Samuel hesitates, approaching the man with caution. ‘Are you … are you okay?’

The man spits, wiping his mouth with his sleeve. He turns to Samuel, gasping, his face ashen and eyes wide with terror.

‘They …’ He points a trembling finger at the house.

Samuel edges closer, dread tightening his chest. ‘What’s happened?’

‘Don’t go in,’ the man rasps. ‘Don’t go in there.’

Samuel’s heart races, its pounding echoing in his throat. ‘Why? What—?’

‘They …’ The man’s voice fades to a whisper.

He shakes his head, eyes squeezed shut. When he reopens them, his gaze is haunted.

‘The girls in there … they’ve been murdered.’

7

Mia crosses one leg over the other and slowly opens her eyes.

She turns over and reaches for her phone on the bedside table.

To her horror, she discovers that she’s overslept. She sits up quickly, a flurry of guilt rising in her chest. The screen is full of news alerts and messages. But after quickly scrolling through them all, she sees that nothing appears to be urgent. It’s Saturday, after all.

She takes a deep breath, relaxing almost immediately.

She doesn’t like sleeping in. She prefers to start the day at least one hour before the rest of the house is up so she can exercise and 19meditate, have a little time to herself. To her, the feeling of having accomplished something before the world wakes up is priceless. She can’t remember the last time she has slept in like this.

She has slept well too. A deep, heavy, sleep full of strange dreams, none of which she remembers.

Thank God Eivind is away on business.

Normally, on a Friday night, she would have needed to go to bed early if she wanted to ward off his advances. And on weekend mornings it was even harder to keep him at bay. After yet another rejection, she would have watched him roll out of bed and trudge off to the bathroom with steps that had become gradually and almost imperceptibly heavier over the years. She’d watch him leave the door open, not making any effort whatsoever to mask the noises of nature. Then after, he would come back out with his hands still wet, drying them off on the hairs of his bulging belly.

For a brief moment, which disappears as quickly as it comes, Mia feels a flash of the love she once had for this man who she knows is fully and deeply in love with her and has been for the past twenty-three years. There isn’t a thing he won’t do for her. At the same time, it was always up to Mia to make sure they got a few pockets of time here and there, just the two of them. Tickets to a concert, or a table at a special restaurant. But when she gave up this task, Eivind didn’t take it over. Why, Mia had never really understood. Was it an age thing? The minute you turn fifty, you stop being adventurous, or eager to please your partner?

Mia looks at the empty side of the bed. She stretches her left arm, grabs the sheets for a second and holds on.

You should be working, she says to herself. A client has moved into an old villa on Tåsen and wants her to decorate their living room in the art-deco style. She’s been over there to get some inspiration, but she’s barely started on her sketches. The deadline is on Tuesday. This Tuesday. Right now, though, all she wants is coffee and breakfast.

Damn. How could she sleep in like this?20

Eivind pops into her mind again.

Maybe, she thinks, because of a morning just like this. How things could be.

A future that would be worth living for.

Would that future include her husband or not? That’s the question. If she stays, everything will remain the same or gradually get worse. That is just a fact. Eivind will never change. There will be less fun, less joy, less of all the things that Mia desires in her everyday life. Yet, while a life without Eivind will open the doors to a freer existence, it will also throw herself and the family into uncertainty. Financially, emotionally – she has no idea how a break-up will affect their children. Or Eivind, for that matter. But shouldn’t she be allowed to think about herself for once?

Her thoughts are interrupted by the phone ringing.

Mia doesn’t recognise the number. As a rule, she never answers unless she knows who is calling. So many idiots out there are trying to sell something over the phone. She can’t stand it. Mia lets it ring until it stops, then she checks the number online in case it’s someone she knows. The number isn’t listed anywhere. A salesperson then. Probably.

Mia rests her head back on the pillow and looks up at the ceiling.

Choices, choices, choices.

No matter what she chooses, someone will end up disappointed, angry, depressed, hurt. Perhaps even hateful. She hates herself for ending up in a situation like this.

Mia misses her father. Without him, there is no one to talk to now. Not really, anyway. There’s no one for her to confide in. In this situation, her father would have said the right things, like he always did. He would have explained to her which path to take and why.

Mia thinks about the children again, and recalls reading somewhere that by the time your kids reach the age of twelve, three 21quarters of the time you get with them will have passed. A thought which, now that it’s come to her again, almost takes her breath away. Her children are sixteen and twenty-two. How is she going to spend what little time she has left with them? What will that time be like if she leaves their father?

The phone rings again.

It’s the same number. The same salesperson, probably.

Mia sighs heavily.

On the other hand, salesmen don’t usually call again straight away, she thinks. Normally they try at a later time, maybe even a later date. And again, it’s Saturday. Do salespeople really work this hard at the weekend?

It could be a customer, Mia thinks as she sits up and leans against the headboard.

She hesitates another second and then takes the call, introducing herself with her full name.

The voice on the other end is firm and dry. ‘My name is Ramona Norum. I’m a superintendent with the Oslo police.’

The … police?

‘Is everything … okay?’ Mia stammers.

‘I’m standing outside your house. I just tried to ring your doorbell, but nobody answered. Are you home?’

‘Ehm, no.’

‘Okay. You’re Eva Eek-Svendsen’s mother, is that correct?’

Mia swallows hard. ‘Yes. What is it? Is Eva okay?’

There is a short pause over the line.

‘I … I’m sorry, Mrs. Eek-Svendsen, but I’m afraid I have some terrible news.’

8

From my suite on the thirty-first floor of the Oslo Plaza hotel, the capital spreads out before me, a lid of heavy clouds looming over 22the islands in the distance, showers of rain cleaning the dirty streets nearby, everything coated in a late-morning grey. It’s as if the night still can’t quite let go. Even the fjord seems miserable, harbouring dark secrets. On the ground, between buildings that look like Lego blocks, cars are moving jerkily through a maze of light. I’m happy the windows cancel out most of the city’s noise, so that I can concentrate on getting ready for the seminar I’m about to give after lunch.

On the computer screen in front of me, a lovely woman called Inès continues to speak in her beautiful Spanish-English. With the diligence and reserve of a zealous schoolgirl, she answers all the questions I ask her from behind the camera.

I stop the recording and go back a few seconds and press playagain.

I was right. When I asked Inès if she has ever committed a crime, she placed her index finger over her suprasternal notch. I smile to myself and make a quick note on my already towering stack of papers.

I’m hoping the seminar won’t last too long. The margin I have for making the flight to California, where I’m going to be spending the next week teaching, is a bit too tight for my liking. I won’t even have time for a quick snack at the swish Oslo Airport lounge.

It’s almost noon when there is a knock on the door.

I open it to Jessica Marler, a woman with a wide, ever-present smile who wears her meticulously blow-dried curls with the utmost American confidence. Jessica heads up the communications department at SecureArts, a global giant in the insurance industry – more specifically, in the insurance of objets d’art. As Jessica once said: We have to put a price on a Chagall, even if it’s priceless.

‘Hi Kari’, she says, wiping away a few thin drops of sweat from her upper lip. ‘Are you ready? Sorry I’m so late.’

‘That’s fine. Let me get my computer and notes.’23

After I grab my things, I pause for an extra second at the full-length mirror, adjusting my hair ever so slightly, then say: ‘After you.’

‘I’ll introduce you first,’ Jessica says over her shoulder as our high heels play a soft rhythm against the heavy hotel-corridor carpet. ‘And then I’ll leave the stage to you. Is that okay?’

‘Of course.’

Jessica gives me another one of her exuberant trademark smiles.

On the ground floor, behind the stage of the hotel’s largest conference room, a pony-tailed sound engineer takes care of us, putting our head mics on and clipping batteries to our waistbands – in my case, a striped one.

‘Can you please put your cell phone in flight mode,’ he says. ‘It might pick up some signals on the sound system.’

‘Of course.’

I take it out of my jacket pocket, frowning at the display, which is full of notifications, the last of which being a text from my dad, sent to me just a few minutes ago:

Can you call me?

I type in a quick reply: Can’t, I’m about to go on stage.

Dancing dots appear on the screen. I wait for my father’s answer.

It’s about the murders at Son.

The murders? Which murders? I’ve been prepping for my seminar all morning, not paying attention to the news.

I quickly scroll through earlier notifications, and I realise that every serious news outlet in the country is talking about ‘the Son murders’. I don’t have time to check any details, as Jessica Marler is making her way onto the stage, about to introduce me.

Whenever there is a news story about a dead body being found, I always think of Vetle. But my father wrote ‘murders’, plural, meaning that it can’t be about my boy. Dad would have said if it had anything to do with Vetle, and he would have called me, not sent a text.24

So, what did he want to talk to me about?

Do the police need my help in some way?

No, my father is retired now. A request from the police force would have come from Unni Flem, his successor, or Ramona.

I take a deep breath and close my eyes for a few seconds, trying to chase away the image of my son – the one that always appears first: Vetle’s happy face as he breaks the surface of the pool in our garden on the last day I saw him, the day we celebrated his ninth birthday. The image always triggers an avalanche of memories, but most of all it sets in motion a tsunami of hurt.

Pull yourself together, I say to myself, and open my eyes. Get into work mode, put on your ‘I’m okay’ mask. Only other experts in body language will see through it.

I put my left foot on the small flight of steps in front of me. My legs tremble as I climb up behind the curtain. The ambient noise in the conference hall subsides.

‘Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen,’ Jessica Marler says in a strong, confident voice. ‘One year ago, when I learned that our next convention would be held in her hometown of Oslo, I immediately thought that we would have a much better chance of getting our next speaker to find the time in her busy schedule to honour us with a lecture. And, luckily, she has. The brilliant Dr. Kari Voss has devoted her life to the study of memory and body language, to the point where one of the newspapers here in Norway has nicknamed her “The Human Lie Detector”. Dr. Voss is a consultant with the Norwegian criminal police, and a chair at the faculties of human science in Lund, Sweden, and Irvine, California. Please give a very warm welcome to Dr. Kari Voss!’

A round of applause accompanies my entrance. As Jessica heads backstage, I walk out into the centre of the floor, palms open, a sea of smiling people in front of me.

‘Hello, hello, thank you. Thank you very much. And thank you, Jessica, for such a lovely introduction. I’m thrilled to be here with 25you today. To be honest, it’s a nice break from catching criminals, dishonest businessmen, or even reading not-so pokerfaced poker players.’

The audience laughs.

‘Being here, to teach all of you – the world’s finest art-insurance industry agents – how to catch thieves, makes me feel as if I’m on the cast of Ocean’s Eleven.’

Another wave of laughter ripples through the crowd.

‘We are all liars.’

I pause, letting the silence stretch for a bit.

‘Yes, we all are, and the first person we lie to is ourselves. Starting with our own memories: you know that memory you have of the one-year-old you nestling in the arms of your granny? Well, that memory doesn’t exist. It’s pure fabrication. You can’t remember anything before the age of two. It’s biologically improbable. The brain is not yet equipped to remember anything that early.’

I scan the audience, making sure I have their full attention.

‘I’m sorry to disappoint you, but our memories are not as trustworthy as we think. Most people believe that we can tap into our memories as if they are videotapes that we can replay as we please. But that’s not the case. Our memories are tangled up with our life experiences, and the two blend together like milk added to water. Once they are mixed, you cannot tell one from the other.’

A person on the front row coughs.

‘And believe it or not,’ I continue, ‘we can purposely create memories. This is how incredibly malleable our memory is. As a colleague of mine says: “we are memory hackers: we get people to believe things that never happened.” No, ladies and gentlemen, this is no magic trick, nor is it hypnosis. It’s mere psychology.’

I smile at my audience.

‘But before we dive into our memories, we are going to focus on our bodies. Because our bodies speak a silent language that you need to master in your line of work. And that language, ladies and 26gentlemen, is the only truth you can rely on. Absolutely the only one.’

I take a few steps to the right-hand side of the stage.

‘In order to learn how to decipher and read that silent body language, we’re going to focus on a part of our brain called the “limbic brain”. This is our emotional centre. It’s responsible for our survival. And it never ever takes a break. It tells our body – our face, arms, torso, legs, feet – how to react to make sure we survive. I will teach you how to recognise and read these reactions, to get to the truth, because we simply cannot trust words. The only thing we can trust is this silent, non-verbal language, as we psychologists call it. What is absolutely mind-blowing, is that this body language is universal. It transcends cultures and even some disabilities. For example, even people born blind will cover their eyes when they find themselves in a situation they’d rather not be in.’

I notice a person on the front row widen her eyes.

‘Okay, I’m sure you’ll tell me that body language must be a tiny proportion of our communication compared to our speech, right?’

I smack my lips together while tilting my head from left to right.

‘Well, you couldn’t be more wrong. Some experts say that we exchange over eight hundred non-verbal signs during a normal conversation, representing sixty to sixty-five percent of our daily communications. And if you’ll allow me to say so …’ I cup my hand around my mouth as if I’m about to tell them a secret ‘…when we make love that number reaches a hundred percent, if it’s done right.’

The audience bursts into laughter.

I wait for it to die down before continuing.

‘Earlier, Jessica introduced me as a “human lie detector”. It sounds a bit pompous, maybe, but actually, the reporter who gave me that nickname couldn’t have been more bang on. What a lie detector detects is not the lie per se, but the emotions that lie provokes in us. And this is what we will do, together, today: we 27will detect the lies by paying attention to what the body is telling us. Because, ladies and gentlemen, we are all Pinocchios. We literally are. When we lie, our nose literally grows.’

I tap myself at the tip of my nose. The audience laughs again.

‘I can assure you, I’m not making this up. We can’t see it, of course, but the lying causes a tiny swelling that provokes an itchiness that makes liars scratch their noses.’

This time the crowd remains silent.

‘There’s a profusion of tell-tale signs like that hidden in our body language. I won’t be able to teach you all of them today – they’re the fruits of decades of research and observations – but what I can give you is a simplified map that will help you avoid falling into the trap of generalisations, for example thinking that the person who crosses her arms over her chest doesn’t agree with something or is distancing herself from a situation. It can actually be the opposite. What I’m about to teach you, will not only help you untangle the truth from the lies you encounter at work, but it just might be of some use to you at home as well.’

Whispers spread through the room like a shiver.

‘Yes, yes,’ I say. ‘Lying children, lying teenagers, lying … spouses.’

An explosion of relieved laughter runs through the crowd.

‘To start our afternoon together, I suggest we play a little game.’

My suggestion is met with an enthusiastic applause.

‘This morning, Inès – your lovely colleague from the Barcelona office – agreed to team up with me for a little experiment.’

A spotlight singles out Inès on the front row. She shyly gets up and waves to her colleagues.

‘I interviewed Inès, making her lie on purpose in reply to a few personal questions. I’ll let you watch the interview we recorded, and then we’ll meet up again in about fifteen minutes to play detectives and uncover her lies, just by looking at what her body is telling us. I’ll see you again in a little bit.’

On the screen behind me, the SecureArts logo lights up. As I step off the stage, the recording begins.28

As Inès is answering the first question, I open the door at the back and slip out. I quickly take out my phone to deactivate flight mode, seeing straight away that my father has sent me another message, asking me to call him as soon as I’m available.

While on stage, I had managed to push away the uneasy feeling that had formed in my gut. Now it’s back in full force.

9

‘What is it?’

Police Superintendent Ramona Norum catches the eye of her colleague, Henrik Meyer, in the mirror. The elevator is slowly taking them to the basement where the police service cars are located.

Meyer tucks his cell phone away in his jacket pocket. ‘Can you enlighten me,’ he says, exhaling hard, ‘as to why you think it’s imperative for us to respond to a murder case in Son on an otherwise calm and quiet Saturday. Last time I checked, Son isn’t in our jurisdiction.’

Ramona smiles to herself. Henrik Meyer is sixty-three and in his final years of active service. He’s spent most of his career doing his best to avoid administrative work. He’s proud to call himself one of the force’s foot soldiers – a real policeman, not a PowerPoint prophet – he thrives on actual detective work out on the streets. However, that doesn’t prevent him moaning whenever the job means they have to get out of their comfortable office chairs.

Ramona has been anticipating his protest. ‘Because the summer house where two teenagers were killed last night,’ she says, ‘belongs to a married couple who live here in Oslo, out on Bygdøy. Same goes for the victims. Meaning that this case is going to end up on our desk whether we like it or not. I thought it might be a good idea to be a bit pre-emptive. There’s not much going on today anyway.’29

‘Except for ten Premier League games,’ Meyer replies with a snort. ‘There’s a local derby in Manchester, among others.’

‘Oh shit, I forgot about that. My mistake. Okay, let’s go to the store instead. Get some beers before it closes.’

Meyer grunts.

Ramona smiles. Despite all his antics, she has learned to appreciate Meyer. She knows that in a shitstorm, he’ll always be right by her side, rolling up his sleeves.

In the basement, Ramona opens the doors to a brand-new BMW with the click of a remote key.

‘You’re driving?’

‘Don’t tell me you have a problem with that too?’

Without answering, Meyer reluctantly shuffles round to the passenger side. Ramona smiles again and gets in behind the wheel.

Ramona follows the E18 along the Oslofjord. The weekend traffic is dense, the day cold and grey. Inland, a thin layer of mist is covering the surface of the water.

‘The victims,’ Meyer says, clearing his throat. ‘Do you know anything about them? Do we have their names yet?’