Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

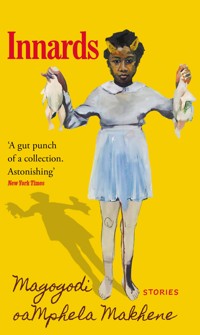

'A gut punch of a collection...it astonishes as it reveals how malignant political forces can both ravage and vitalize the human spirit.' New York Times Set in Soweto, the urban heartland of South Africa, Innards tells the intimate stories of everyday black folks processing the savagery of apartheid. Rich with the thrilling textures of township language and life, it braids the voices and perspectives of an indelible cast of characters into a breathtaking collection flush with forgiveness, rage, ugliness and beauty. Meet a fake PhD and ex-freedom fighter who remains unbothered by his own duplicity, a girl who goes mute after stumbling upon a burning body, twin siblings nursing a scorching feud, and a woman unravelling under the weight of a brutal encounter with the police. At the heart of this collection - of deceit and ambition, appalling violence and transcendent love - is the story of slavery, colonization and apartheid - and it shows in intimate detail how South Africans must navigate both the shadows of the recent past and the uncertain opportunities of the promised land. Full to bursting with life, in all its complexities and vagaries, Innards is an uncompromising depiction of black South Africa. Visceral and tender, it heralds the arrival of a major new voice in contemporary fiction.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 295

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in the United States of America in 2023 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2023 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Magogodi oaMphela Makhene, 2023

The moral right of Magogodi oaMphela Makhene to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

“Indians Can’t Fly” first published by The Drift © 2023 by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene, “Dr. Basters” first published by American Short Fiction © 2022 by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene, “The Caretaker” first published by Ploughshares © 2016 by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene, “The Virus” first published by Harvard Review © 2016 by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene, “Jesus Owes Me Money” first published by Guernica magazine © 2013 by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene are reprinted by permission of the author and Aragi Inc. “Innards” first published by Granta © 2019 by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene is reprinted by permission of the author.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 80546 097 8

EBook ISBN: 978 1 80546 098 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For our Gods, my ever-living ancestors:

bagaMphela le baNkadimeng. Bare kwena ga e tsene metseng!bagaMakhene le baSepeng. Kgabo tse dinhle!

For my grandparents especially—Johanna Togoloane Mahlakoand Edward Kwetjane Mphela.

And for Mommy, Dimakatso Maks Mmadiphisho MphelaMakhene—this praise song is for you!

Contents

Bua

7678B Old Potchefstroom Road

Indians Can’t Fly

Black Christmas

Star-Colored Tears

Innards

7678B Chris Hani Road

Dr. Basters

Jesus Owes Me Money

The Caretaker

The Virus

Sereto

Acknowledgments

Bua

Everyone claims ancestral royalty. Even slaves. No one imagines their beginning damned or marred by mediocrity. No. The likely telling is of glory. Of kings and paramount chiefs prostrating themselves like bush rabbits fearing our forefathers—those fearsome foxes. Of queen mothers throwing their firstborn daughters into our bloodstream like eager spawn sifting salt water for sperm.

Our star was born long-tailed, the old man liked to say. We were kingmakers and twin sires. Even our cows came in pairs. We made rain fall in Great Zimbabwe.

No one asks him, How, then, did the Boers and the British happen? How did such a strong and certain seed turn slave on its own ancestral land?

So much of who we are is fiction. The old man’s wife used to tell him that. And that only a woman could be God. Only Woman—who takes heat, sweat and sin and turns it into flesh; into sacred being.

Carrying life teaches you that, she’d say.

Maybe that’s why history forgets our grandmothers. They are written in the womb.

7678BOld Potchefstroom Road

They came riding cattle lorries. Their whole world traveling with them, herded onto truck flatbacks. Thick woolen blankets folded into warm wishes. Matching chairs and lorry-scratched dining tables bought piecemeal on layaway. And head-scarved Granny, wrapped at the waist in a brown plaid blanket that doubled as cot when the baby fussed.

Out, those cattle wagons drove. Out. Past the city, Park Station behind them and old Ferreirasdorp decaying with the sunset. Out, meandering with Commissioner Street beyond an empty yellow wasteland dumped by Crown Mines. Out and into a barren veld bordered on either side by municipal sewerage farms.

They came like that, curious about this place. Curiouser still—entire families and their lives packed into the same space where a lamb probably hoof-kneaded sheep shit on its way to the slaughterhouse yesterday. The lorry beds were all metal and wooden plank, with mesh cage roofs like a chicken coop. Swine haulers, those lorries, now overloaded with babies, steamer trunks and loose cupboard drawers. Everything unhinged.

I wasn’t sure which family was mine. And by the standing around and waiting, pointing at numbers, eyes searching, these natives themselves seemed uncertain which of us was whose.

A short man with an orange mustache and a squat face took control, clipboard in hand, a neat row of pencils peeking from pocket. “Yebo Baas,” the men answered him, showing their dompass. The Baas then gave each man a key with his number. Some slipped a few shillings into his hand for another number promising an indoor toilet. Then they packed off for this house. A thin mattress balancing on the wife’s head. A heavy washtub carried one-one on either side by the children.

—7678B? Clipboard Baas called my name. A man in a dark suit walked toward me, his wife behind—her white heels stepping into his imprints, so that their soles cleaved to one another in the dust. The children’s weren’t far behind. Stop, Granny shouted, Stop! Stop that running! But the mother was running, catching her husband’s shadow and moving past him, toward me. He watched her; let her. So that a woman first entered my threshold.

Her heels were soiled by now, the color of rust, but she didn’t notice, running into my rooms, thrusting windows to the world, standing with her arms the width of my walls. As if embracing my full girth, everything inside me. As if to say, Yes. This will do.

Only with her children also running in and out of the rooms—rooms so small they could be folded up and stuffed into the lorry- fastened wardrobe—only then did the dirt floor disappoint her. Little feet kicked up dust and stone. The wife looked around, shushing the children, but her gaze met her husband’s and the steady smile growing on Granny’s face. We’ll have to plaster, she said. And . . . paint.

Men arrived. In long trousers that sat low, far low, below bare chests and taupe sweat. Ethel—I know her name now—Ethel hummed as she cooked, knifing tenderly through gummy seeds, fingering small tastes to her tongue. The smell of fried onion skin sizzling in sunflower oil and ripe tomatoes filled me, as if I were lungs.

She brought a tray out to the men. The tray held a small washbasin with soapy water and a clean cloth. Next to this was a large dish offering last night’s leftovers fattened with fresh tomato gravy. Ethel bent to pass the cloth and washbasin around, putting the food on the ground. Bodies close, she smelled how the sun made itself rancid on the men’s skin. She wound her neck—slowly, absently. When she took her lunch inside with Granny, her fingers caressed her nape just as absently, the same space between neck and spine that Tom’s hands and tongue had chiseled smooth late last night.

—It’s quite tasty, Granny said.

—Yes, Ethel smiled, e monate.

Tom—Ethel’s husband—was the sole sound I heard whispering to the night. It was quiet. Ethel was quiet, nervous their hunger would stir the children. She forced her pleasure into the pillow. A pleasure as silent as muffled pain.

—Have you heard the one about the Boer and his missus? Tom asked.

—No, she shook her head, gently, as if a full head shake would wake the baby beside them and the children on the now plastered floor.

—The missus, said Tom.

—Asks her Baas . . .Tom stopped. Chuckling.

—That’s how krom daai man is, he says, still laughing.

—He orders his wife call him Baas!

Ethel smiled, wry. I could see her bare teeth flash at the asbestos roof that is my own mouth.

—Anyways, Tom goes on, the missus asks her Baas: But where were you, just now getting in, so vroeg in the morning? Where did you spend the night? The Boer scratches his head a bit and thinks quick on his feet:

—Ag, man, vrou! the skelm begins. Woman! I was at that friend of you’s. Susanna.

Go on, the wife’s face seems to say.

—Well. Her husband took a turn. For the worse. And just like that . . . Poop! He snaps a finger. The hairy bliksem died. He’s dead! The Boeremeisie sniffles. You know how you women are. Seeing this, the Baas is bloody chuffed with himself, swelling at his stupid cleverness. He doesn’t even notice his missus scratching about till she’s fully dressed, fetching her gloves and looking for a scarf to cover her head.

—Vrou? he asks. Waarheen nou?

—To Susanna’s, the missus replies. She’ll need to borrow you another night and maybe some other things also.

—Nee man! says the Boer, quick-quick on his feet, again scratching that head.

—They ring while you dressing. Turns out that old fat bastard isn’t dead after all. He rose. Up! Just now-now. Like Jesus! He rose up from the dead!

Ethel put a finger to Tom’s lips, stifling their giggles. She peered over his body at the young ones, sleeping below the mattress. Little chests rose and fell with the deep breath of children’s dreams.

More families arrived, taking up the empty numbers all around me, until the neighborhood pulsed with fat gossip at communal taps, with hammering nails shouting response to workmen songs. Radios belted out news from faraway places where news happens—places so scary the fear seeped through the speakers and settled beneath my trenched roots. Stray chickens wandered in. Flocks of ashy children pecked about the street in gray packs that smeared their idleness and wonder everywhere people sprouted. Life grew without record or resolve. Daily routine—sewerage bucket dumps early mornings and coal deliveries before sunset—made rhythm out of time.

Ethel walked into the kitchen, tired, fed coal to the furnace and placed a large round-bottomed kettle on the boil. Her daughters, older now with small seeds of womanhood, clung to sleep under the table. She sang, softly, a silly song about a girl who slept past sunrise, her crops shriveling into snakes. The girls woke. Ethel poured a cup of black tea and carried a large tin tub, filled with Tom’s bath, into their room.

Tom’s suit jacket, pants and tie lay spread across the bed like a Kliptown jumble sale. His shirt hung from the door handle, a soft yellow stain warming its armpits. After washing, he reached first for a sleeveless undershirt, then his shirt. Ethel stood behind him, folding his work uniform—Tom never left or returned in anything but a suit, red-feathered fedora in hand. He unraveled his tie’s knot for a fresh start: right end over left, mimicking the shape of a cross. He fussed, looking into the mirror, then at his wife’s double.

—You look like someone getting late for work, Ethel said, naughty mischief overtaking her smile.

—But my shoes don’t even shine yet, Tom pointed.

—Okay, okay, Mr. Very Important, High-Class, Top-Label Shoes. You keep powdering your nose. You keep preening and primping and you’ll really be late this time.

Quickly, in a single fluid motion, Tom spat spittle on the shoes, rubbed hard with his polishing cloth and was out the door.

—Ehn!? Ethel called out, laughing.

—Mr. High-Class Shoes! She charged after him. What about your uniform?

Tom walked out, barefoot and skinny-chested, soon worrying earthworms between his spindly fingers, smelling the soil and clamping its slight sweat. It was the weekend. He bent low to the ground, digging beds for black arum lilies with a retooled serving spoon, imagining the arums’ elegant swan necks reaching one day beyond his knee. He came next to a frail jacaranda sapling, carrying water to it on his head, like a woman. His plants took root. They didn’t believe, as authorities do, this land too sterile—a suitable plot to blackspot with natives. Maybe it was the sewerage fattening the soil. Engorging this parcel of uncharted, unwanted earth.

Lording over Tom’s Eden, as if greening the grass, was a red-hatted gnome with a seriousness to his mischief—a voluminous beard and furrowed brow, a plump but upright body and unseen, hiding hands, held behind his back. I wasn’t bothered by this midget little he-man. Grass leaves must’ve seemed a thick forest to his eyes, the distant hydrangeas an unreachable land. I could see beyond the hydrangea hedge, to the invisible fence within its branches. I could see beyond that even, to where the garden met an unpaved road. Old Potchefstroom Road. Named for a sleepy little dorp where Brits held Boers in concentration camps, before the Boers built a giant concentration camp out of the whole country.

Weekends also brought visitors. A brother or third cousin carrying urgent news from home.

—Buti, they called Tom.

—Your little uncle’s son is marrying. The bride’s father wants thirty bulls.

—Tjo! Tjo! Tjo! Someone would cluck their tongue, or whistle cleanly, or burst into spastic laughter.

Sometimes Tom had already heard about the trouble—about another relative stripped of his farmland by Verwoerd and the white man’s law.

—Two hundred fifty rands? he’d ask, stacking the bills on the table. At least that’ll get him some blankets. An unforgivable winter is coming, Tom would sigh.

Guests were received in the front room. At the proud dining table scratched by the cattle lorry on the drive out. Tom sat opposite his visitors—there wasn’t enough room to squeeze a chair at the head. Ethel served tea on a tray, her sugar bowl matching the rose-blooming cups. The milk jug, also part of her set, had a jagged chip on the lip—like a pretty girl with knocked-out sawteeth. Visitors stayed for at least one meal. This was understood as soon as an unexpected but booming knock filled the house. Ko-ko-ko! the knuckles rapped, despite my front door standing wide ajar. If it was Sunday, the children cursed under silent breath, knowing a minor chicken piece would be split six ways between them, the coveted drumstick now firmly out of the question. Their next best hope was an empty bag. If the relative’s sack was light, it held no overnight plans.

This was how Ethel’s youngest brother, King, arrived. From Transkei. He showed up on a Sunday morning. Ncgo-ncgoncgo? His knock was light, uncertain. Come in! Ethel shouted, throwing her arms around him on seeing who it was. The girls—helping with chores, the boys playing outside—looked on, shylike. He took off his hat and a tatty, threadbare jacket. He shook each girl’s hand and asked their names in deep, rhythmic Xhosa. Kingsley carried not a single bag. He stayed a whole month.

Late nights, King hid outside. He’d climb into the big metallic coal bin. Sometimes it was full but he’d force his way in, parting the rock with his body. The police never checked the coal lock-box, hard to say why. And after each dompass raid, he’d emerge from the shiny bin sweaty and soot-black.

—Sister, he’d sulk, this is how you live?

But Ethel would only poke fun, mocking his Cape Colored–like blackface, sommer another Boesman cruising the Coon Carnival.

—So, King. You’d rather turn Colored than go in a mine shaft and sing Môre! Baas? Ethel would ask, laughing, trying to pump air back in the room by going straight for the jugular vein: Kingsley still hadn’t found work. Which meant he had no white man to sign his papers. Which made Kingsley the thing they stamp in a dompass before deportation: “Prohibited Alien.” But instead of Ethel’s words stinging, Kingsley would strum an invisible guitar in response to the jabbing, everyone laughing. He’d bare his teeth through his coal-colored black-face, mimicking Coloreds mimicking black savages at their New Year’s Eve minstrel show. The children would join in also, singing and blowing make-believe horns, clapping whatever they could find into tambourines.

Less than a month later, Kingsley gave Ethel another reason to play make-believe, this time with the old woman Makhadze. It was after Tom answered an unmistakable Bang-Bang-Bang! late one night. Someone tipped them off, Ethel later told Tom. The police had barely considered Tom’s papers, swatting off his identity book like a clumsy flea.

—We hear you have a fat rat squatting around here, the black policeman boomed.

—Is that right? another asked Tom, making a show of tapping his baton.

What happened next is the two policemen walked Tom outside, toward the back of the yard, behind the toilet. Made him unlatch the box. Shined a blackout beam onto the peat rock. The coal lit up under torchlight, glistening, like something strangely beautiful. Like burning candlewick—so intently black. Or pools of oil resistant to rain.

Somebody told them, Ethel repeated in whispers. They’d blown out all the candles and crept into bed. The girls in the kitchen. Granny on the sofa and the boys under the scratched dining table. Everyone wide awake, pretending faraway sleep.

—You have to do something, Ethel begged Tom.

—Something like what? Tom’s tone was sharp.

—Isn’t it enough he wasn’t in the box? They didn’t catch him, Ethel.

What else do you want me to do? Shit out a fresh dompass?

—Tom, please! Ethel pleaded. We don’t even know where he’s sleeping.

—He’s a man, Ethel.

—A Missing Man!

Ethel never shouted, never raised her voice over Tom’s. Tom sighed. Seeming to shrink from the effort.

—Every man passes through this, Ethy. You think we want to part our arse for the Baas and sleep in his jail cells?

It was harsh, what Tom was saying. But he said it soft and even, like a loaf of industrial-grade butter.

—King is a man, Ethel. He’ll survive.

Makhadze lived in the dreamworld. She was known to fetch stubborn babies and their mischievous spirits who refused to wake from their ancestors’ dreams and into birth. Whenever Ethel’s moonbelly burst under secret tide, Makhadze was long in the room, preparing with Granny. Even Granny knew better than to argue with Makhadze. She’d ably delivered the twins after they came feet first. And she was rumored to have unsettled spirits sheltering beneath her bed. Makhadze disquieted me. She listened too intently, parsing out what others called house sounds. I held my breath, knowing Ethel trusted her. Needed her.

—She was an old woman, Ethel told Makhadze, describing a dream.

—Very old. Her skin pooled around her joints, like she could step out of herself if she wanted. A dark woman. Black. Black. Black. She kept smiling at me in the dream, but her eyes didn’t light. Only her eyebags moved. When she smiled, her eyebags made me think she was a man. We slept on the floor—me and this old woman—back to back. Me facing the wall. I started nodding off but then I felt cold hands. Cold strong hands pressing my backside. Not shy. Firm. One-one, holding each cheek. I turned around to ask this gogo, What’s happening? But her whole face was suddenly those heavy eyebags, twitching. And a beard grew fast and thick, covering her face. I started feeling very sick, Mme Makhadze. And when I woke, the vomit was also thick. Like rotten oats.

—Your dream is not good, Makhadze sniffed.

She carried a small container of snuff inside her skirt pockets.

—Chinaman is going to draw a penis or a dead woman today. Number thirty-six and Number twelve. If he draws the dead woman, your brother will live. But if it’s a penis . . .After Makhadze left, Granny cursed the wrinkly Venda matron a savage heathen.

—Sies! Granny said, I wouldn’t wash my panties in water from that Makhadze’s house.

—Phooh! Granny spat.

But Ethel wasn’t listening.

The m’China who ran fahfee always appeared with the sunset. He was a stumpy man with a perfectly round face and upstanding imp ears. He spoke enough Zulu to stave off cheats, but mostly his exchanges were hand maneuvering and fluid gestures. He’d idle at my street corner with the car window halfway down, under a wide-brim fedora and careful guard. For a long time, his numbers runner was Talent. But she hit the big time pickpocketing, so she passed her position to her teenage grownish-womanish child. When this girl took over, all m’China’s bets increased one bob, which she pinched.

As soon as m’China’s car came to a stop, Talent’s daughter scanned the streets for police before hopping inside. She kept each day’s collection between her breasts, like her mother. But being much flatter, the pouch protruded awkwardly through her clothes, as if she was nursing an eager cock with a large comb. m’China would whisper the winning number to her before she fished out the pouch. The girl then got out of his car to signal who scored, galloping through the streets for a horse, twenty-three, or clucking stupidly if it was thirty-one, a chicken. Every number had a sign and sometimes, a winner.

The day Makhadze predicted a penis or death, Ethel kept watch like a hawk, desperate for a sign. Long before sunset, she was peeking out my front windows, eyeing the corner for a car. It was too early. Normally she’d be on her knees scrubbing floors, her plentiful buttocks polishing something stuck in the air. She moved away from the window and got the broom, reaching under the closet and table, collecting yesterday’s dust, getting into crevices I always forget tickle. Next she polished furniture—the three-person sofa with crocheted headrest doilies, the scratched dining table they had to unscrew to squeeze through my rear, the mismatched chairs—each made with a different room in mind. And then the glass cabinet that sealed off the little space in the room. Done dusting, Ethel stood outside. The sun was still high. And really, more cleaning made up her day.

There was a healthy stack of Drum magazines to fan artfully so that Miriam Makeba added a pop of yellow to the otherwise dull wood table. There were the doll-size Coca-Cola bottles with fancy red cursive to rinse and display. And Tom’s fake gold ashtray set—a work award for ten years’ Anglo-American service, even though Tom didn’t smoke—had to be cleaned. After preening my innards, it was time for a bath and some half-hearted gossip, Granny failing to distract her as they both peeled supper’s potatoes.

Because Ethel was not the sort of woman to play fahfee, was just the sort gamblers clacked tongues over and called beter koffie—She thinks she’s better than us—Talent’s daughter took a curious and skeptical interest in her bet. m’China’s car was still idling when the girl entered Tom’s garden.

Talent’s grownish and womanish daughter would’ve seen my public pubic hairs—trim and thick green grass—countless times from the street, but she seemed impressed walking through the verdant smells trapped in my unlikely oasis. And she studied Ethel. And Ethel’s reaction. Thank you, my baby, Ethel said, handing the girl an orange. The money was much more than expected. Beginner’s luck, Granny scoffed, reminding Ethel in front of Talent’s daughter that gambling is for harlots. Thank you, Ethel repeated, a crack in her voice because death won. Number twelve. King would live.

With the money, Ethel decided to finish paying layaway on the children’s Christmas clothes early and take pictures while everything was still new. Getting ready took a whole entire week—cleaning every inch of my flat-footed floor bottom and furniture, pressing every collar, trimming every coil of hair, overseeing each shoeshine. Do your father’s first, Ethel instructed. Don’t make me slap you; those shoes better glow!

On the long-awaited date of the appointment, the photographer was late. That’s just like a kaffir, Granny said, folding her arms into a barricade. But she changed her tune after Ngilima arrived, setting up his large floodlights and shiny umbrellas in the front room behind my hearth—my heart chamber. They won’t bring bad luck, Ngilima promised with a grin. Granny still refused to pose in pictures paid for with devil money, but she conceded the silver umbrellas had to be good luck. The white man thinks of everything, she said.

Ngilima directed them. Ethel and Granny on either side of the three-person sofa—Ngilima having finally charmed Granny into frame, with peppers of unintelligible English Granny did not understand but still found impressive. Ethel—wearing black high heels and hot-ironed, egg-white-stiffened hair that still clutched, midair, to the C-wave shape of her curlers—held a small leather handbag primly. She rested her other hand on Tom’s shoulder. Tom sat center, wide legged on the sofa and flanked by his children, one on top of the other. Before shooting, Ngilima stepped behind everyone, lifting a large framed print to the wall. It was a painting of someone’s chocolate-brown baby with welling eyes and shiny afro curls, her shoulders slumped and with two static tears that could just as well have been birthmarks. He hammered expertly, small pricks I barely felt, mounting the frame.

Everyone was excited.

—One! Two! Three! Ngilima shouted.

The force of the flash stunned. Cheeeeze! everyone hollered. Everyone but Granny. She stared straight ahead—unmoving—determined not to ruin her first portrait. They made two more. Ethel standing behind Tom, Tom sitting at the dining table, a serious book in his hand. The radio was placed in the fore-ground, but low enough to still see Tom. Then one more of Ethel reclined across the sofa with a faraway look, the same look as Drum magazine’s back-page-babes sitting on beachy sand, listening to the sea.

When Simon Ngilima returned, the film developed, Tom was dead. Granny sat with Ethel on the mourner’s mattress. King and Tom’s brothers saw to everything, choosing a photo from Ngilima for the Bantu World announcement. Carefully storing extra copies in the front room, at the back of the glass display cabinet:

Tom, né Welcome Mbukeni Thembeka wa Fakude of 7678B Old Potchefstroom Road Diepkloof Zone 6 Soweto died last week on Sunday June 17, 1973. Survived by mother, 8 childrens and wife. Attended Lovedale High School, to Form VIII. Once shook hands with H.R.H. Queen Elizabeth II. Service begins 8:30 A.M., Moroka Parish. Hearse will leave for Nancefield Cemetery 8:00 A.M. sharp.

After thirty days, most of the relatives left. Everything was quiet with a brooding calm. Ethel rose to make tea. She sat back down with a cutout copy of Tom’s funeral announcement and their family album. She looked at the photos. The radio in one picture commanded the shot. It was ugly. Ethel concentrated on her broad smile and the dull ache in her dimples that day. She took the photo out of its casing. Brushed a lint dust from Tom’s big nose. He was very black in the photo. Blacker than remembered. And something else. He wasn’t looking at Ngilima in any of the photos. Tom held himself with a private preserve. He only looked at Ethel, even when she wasn’t in frame. She put the picture back in the album book. Tried to swallow strong tea.

And then they came. Riding hippos. It was a Monday. The hippos were armed with five soldiers apiece—guns at the ready. Parked at m’China’s corner, scraping Tom’s hydrangea hedge. Imposing, these hippos. Cast long shadows over mine. Tom’s little he-man, his bearded garden gnome, looked infantile and lost, surrounded by all ten white soldiers. They had a helicopter also, hovering overhead. I can still hear the chopper’s wings clipping the air into fury. And see people across Old Potch Road, scurrying behind fences. Gawking. I can see them standing behind their gates, parting curtains, peering out, softly clicking and clucking dead tongues.

And then the soldiers scale my walls, stomp onto the asbestos-roof-space that is my crown. Spray a big X, in shouting red letters, across this crown. Next, my innards are guttered: Tom and Ethel’s bed. The kitchen cabinets and round-bottomed kettle. The old gramophone. New radio. Everything thrown out, into a low lonely mountain. The soldiers struggle with the dining table, just as Tom had. Finally, they hack down its legs and stack its wood at the gate, blocking my garden path.

Ethel does not resist. She doesn’t even read their note. She already knows. She’d tried convincing the Rent Office man who came by to serve notice.

—I have money, she’d begged.

—My son, he’ll find work.

—Asseblief, she’d begged. Please, my Baas!

—Next week, my son will have dompass. You come please check us next week.

But the councilman was firm.

—No, Mrs. Fakude. I’m very sorry but you cannot expect us to break the law every time a native is stabbed. In this country, the law is the law. We cannot have a widow as head of household when you are not even a citizen. You must go back to where you people come from. It says here you are Xhosa. So Transkei, isn’t it?

—Look. I’m very sorry about your husband, but there’s a very long list of qualified natives. Men with proper employment and their families, you understand? Ek is baie sorry, the councilman said.

In my living memory of that Monday, Granny does not stop her wailing. She is not loud, but her body keens back and forth, back and forth. Her now grownish and womanish granddaughter—whom Granny carried from the place where they were forcibly removed, where they were herded out in cattle lorries—that now-womanish granddaughter now unsways Granny, now wraps a plaid blanket around Granny’s shoulders.

The hippo’s rubber tires are very big. And wide—the whole street needed to clear way for their passage. All of Soweto’s dust stirs in the hippo’s wake and settles on their things. Ethel teeters through strewn furniture, toward the front-room cabinet. A cut in its shattered glass makes it look like diamond water has sprinkled everywhere. She slides the cabinet’s door open. Her pink teacups with English roses survived the move. The fake gold Anglo-American ashtrays also. Ethel reaches beyond these things, pulling out the photo album. Inside, Tom sits at the proud dining table, reading a book. Granny glares ahead, beyond the moment. Afraid to blink. Ethel rips out the photo, buries it firmly inside her breast.

Indians Can’t Fly

The blue of the water was a bright electric hue.

It made sounds: clapping rain sounds, trickling ice sounds, running water; water running . . . rushing in cold waves and against river rhythm.

Splash! Spumes exploded. Spit spray. Water breaking on the ceiling shore. The waves blocking out cries from the hose welting rubber into her back, hoarse shouting rattling something free deep inside her ear. The water blocked out the barking. Six policemen with toad screams and erect dog ears howling right into her ears, shooting spittle straight inside:

—Jy sal kak, Girlie! The fat one farted.

—Where is Jappie?

—Where’s your Boesman?

—Sies! Four Eyes spat.

—What would your father say? You fokken motherwhore!

She felt thunder fill the room, but couldn’t hear Colonel McPherson and his men. She was swimming in the ceiling.

The water was warm. Sweet. There was no salt in her mouth from her broken nose bleeding and pores sweating and skin swelling. She had never swum in any ocean. How could it come so easy? Buoyed by big waves. Floating above the swaying room and seeing herself a speck or a spore somewhere down below—suspended between two chairs, hanging like a lemur snatched from the wilderness. A human helicopter.

She didn’t need that swinging body to swim. Still, she felt the water parting under her pressure, and because she wasn’t wearing anything, because they kept her unshod on a gleaming cement floor in that naked room, she was tickled by air bubbles swimming in and out of her, as though another ocean lay corked between her legs. The water was endless. A faraway shoreline. She stroked her arms out and wide like a peacock fanning its feathers. The water made a snowman of her ripples. She was swimming in a daydream. From somewhere beyond seashore came sonic echoes, faint dispatches from a distant land:

—We know everything, they said.

—Everything Everything Everything

And Everyone is talking

Talking

Talking

Talking

They ratting you out

Talking

Talking

Talking

She closed her eyes and swam deeper, to the sea floor. From far, weeping willows swayed with the current. A dense forest of fir firmly rooted, swinging to and fro. Forward and backward. Swaying. Gently. So gracefully. Like little playthings dancing with the wind.

As she swam closer, the sea thicket thinned. Those faraway willows revealed themselves: amputated arms with missing forearms and fingers. The playful trees were old men with wispy beards and severed front parts—nothing to cover themselves. She thought she recognized a long dead comrade among the floating forms. Swimming toward her. A growth of strange people carpeted the ceiling sea. Their weight pressed upon her until the forest was dense again and everywhere around her: water. Water everywhere. Choking. Forcing pressure up her nostrils, injecting a sharp sting to her brain.

She could not swim. Since she was a little girl reared on aubergine curries and the bright scent of sugarcane, Krishna could not swim. When she opened her eyes, the sea creature that had turned the ceiling into a burning blue—a violent rush of white waves in which an ocean sprouted, in which she felt herself swimming—was gone.

The floor was cold. Cement, perfectly poured. Her single black braid coiled on the hospital-friendly concrete like a serpent charm. Everything sterile. Shiny. A rubbish bag rustled around her head. It suffocated her screams. Water rushed forward, pressed by firm hands against her face, held tightly in by the plastic hood. So that the water found her open nostrils and screaming mouth. This time, she could hear herself. There was no ocean sound. Her ceiling-sea, gone.

Krishna sang every song in her body. Gauhar Jaan songs she’d hated growing up. Hanuman Chalisa verses Ammachchi pinched her into singing. And Brenda Fassie Zola Budd. And Queen, again and again: Save me, Killer Queen.

When her throat grew hoarse on every chant and lyric she remembered, the thing she tried to muffle washed up afresh:

—What you tell them that for?

—What!?! What did I say?

—About Jappie. You told them about Jappie. And Suliman. You nodded at their photos.

—But I said nothing.

—Right! Didn’t have to. They have eyes and ears everywhere.They know everything.

—Really? You really believe that?

—How else they put it together so fast? About you and Jappie?

—Someone must’ve told them.

—Someone like who?

—Suliman? Jappie? No. But not Jappie. He’s in Africa now.

—So Suliman. He’s talking. Everyone’s talking. And now this Jappie . . . Poof—gone!

—What are you trying to say?

—Be reasonable, Krish. Give them something. Anything. A small bone. It’s been three days already.

—Three? What you mean three? I crossed off seven. Look, here . . .

—Does it matter? Don’t be stupid, Krish. You want to be the next Indian who couldn’t fly out of the tenth floor?

—No! They would never do that! I know nothing.