109,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

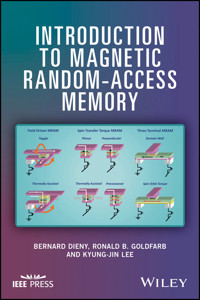

Magnetic random-access memory (MRAM) is poised to replace traditional computer memory based on complementary metal-oxide semiconductors (CMOS). MRAM will surpass all other types of memory devices in terms of nonvolatility, low energy dissipation, fast switching speed, radiation hardness, and durability. Although toggle-MRAM is currently a commercial product, it is clear that future developments in MRAM will be based on spin-transfer torque, which makes use of electrons’ spin angular momentum instead of their charge. MRAM will require an amalgamation of magnetics and microelectronics technologies. However, researchers and developers in magnetics and in microelectronics attend different technical conferences, publish in different journals, use different tools, and have different backgrounds in condensed-matter physics, electrical engineering, and materials science.

This book is an introduction to MRAM for microelectronics engineers written by specialists in magnetic materials and devices. It presents the basic phenomena involved in MRAM, the materials and film stacks being used, the basic principles of the various types of MRAM (toggle and spin-transfer torque; magnetized in-plane or perpendicular-to-plane), the back-end magnetic technology, and recent developments toward logic-in-memory architectures. It helps bridge the cultural gap between the microelectronics and magnetics communities.Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 476

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright

About the Editors

Preface: A Perspective on Nonvolatile Magnetic Memory Technology

Chapter 1: Basic Spintronic Transport Phenomena

1.1 Giant Magnetoresistance

1.2 Tunneling Magnetoresistance

1.3 The Spin-Transfer Phenomenon

References

Chapter 2: Magnetic Properties of Materials for MRAM

2.1 Magnetic Tunnel Junctions for MRAM

2.2 Magnetic Materials and Magnetic Properties

2.3 Basic Materials and Magnetotransport Properties

References

Chapter 3: Micromagnetism Applied to Magnetic Nanostructures

3.1 Micromagnetic Theory: From Basic Concepts Toward the Equations

3.2 Micromagnetic Configurations in Magnetic Circular Dots

3.3 STT-Induced Magnetization Switching: Comparison of Macrospin and Micromagnetism

3.4 Example of Magnetization Precessional STT Switching: Role of Dipolar Coupling

References

Chapter 4: Magnetization Dynamics

4.1 Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert Equation

4.2 Small-Angle Magnetization Dynamics

4.3 Large-Angle Dynamics: Switching

4.4 Magnetization Switching by Spin-Transfer

Acknowledgments

References

Chapter 5: Magnetic Random-Access Memory

5.1 Introduction to Magnetic Random-Access Memory (MRAM)

5.2 Storage Function: MRAM Retention

5.3 Read Function

5.4 Field-Written MRAM (FIMS-MRAM)

5.5 Spin-Transfer Torque MRAM (STT-MRAM)

5.6 Thermally-Assisted MRAM (TA-MRAM)

5.7 Three-Terminal MRAM Devices

5.8 Comparison of mram with other Nonvolatile Memory Technologies

5.9 Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

Chapter 6: Magnetic Back-End Technology

6.1 Magnetoresistive Random-Access Memory (MRAM) Basics

6.2 MRAM Back-End-of-Line Structures

6.3 MRAM Process Integration

6.4 Process Characterization

Acknowledgments

References

Chapter 7: Beyond MRAM: Nonvolatile Logic-In-Memory VLSI

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Nonvolatile Logic-in-Memory Architecture

7.3 Circuit Scheme for Logic-in-Memory Architecture Based on Magnetic Flip-Flop Circuits

7.4 Nonvolatile Full Adder Using MTJ Devices in Combination with MOS Transistors

7.5 Content-Addressable Memory

7.6 MTJ-Based Nonvolatile Field-Programmable Gate Array

References

Appendix: Units for Magnetic Properties

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Tables

Table 1.1

Table 4.1

Table 5.1

Table 7.1

List of Illustrations

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.3

Figure 1.4

Figure 1.5

Figure 1.6

Figure 1.7

Figure 1.8

Figure 1.9

Figure 1.10

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.2

Figure 2.3

Figure 2.4

Figure 2.5

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.7

Figure 2.8

Figure 2.9

Figure 2.10

Figure 2.11

Figure 2.12

Figure 2.13

Figure 2.14

Figure 2.15

Figure 2.16

Figure 2.17

Figure 2.18

Figure 2.19

Figure 2.20

Figure 2.21

Figure 2.22

Figure 2.23

Figure 2.24

Figure 2.25

Figure 2.26

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.4

Figure 3.5

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.8

Figure 3.9

Figure 3.10

Figure 3.11

Figure 3.12

Figure 3.13

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.2

Figure 4.3

Figure 4.4

Figure 4.5

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.9

Figure 5.10

Figure 5.11

Figure 5.12

Figure 5.13

Figure 5.14

Figure 5.15

Figure 5.16

Figure 5.17

Figure 5.18

Figure 5.19

Figure 5.20

Figure 5.21

Figure 5.22

Figure 5.23

Figure 5.24

Figure 5.25

Figure 5.26

Figure 5.27

Figure 5.28

Figure 5.29

Figure 5.30

Figure 5.31

Figure 5.32

Figure 5.33

Figure 5.34

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.2

Figure 6.3

Figure 6.4

Figure 6.5

Figure 6.6

Figure 6.7

Figure 6.8

Figure 6.9

Figure 6.10

Figure 6.11

Figure 6.12

Figure 6.13

Figure 6.14

Figure 6.15

Figure 6.16

Figure 6.17

Figure 6.18

Figure 6.19

Figure 6.20

Figure 6.21

Figure 6.22

Figure 6.23

Figure 6.24

Figure 6.25

Figure 6.26

Figure 6.27

Figure 6.28

Figure 6.29

Figure 6.30

Figure 6.31

Figure 6.32

Figure 6.33

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.2

Figure 7.3

Figure 7.4

Figure 7.5

Figure 7.6

Figure 7.7

Figure 7.8

Figure 7.9

Figure 7.10

Figure 7.11

Figure 7.12

Figure 7.13

Figure 7.14

Figure 7.15

Figure 7.16

Figure 7.17

Figure 7.18

Figure 7.19

Figure 7.20

Figure 7.21

Figure 7.22

Figure 7.23

Figure 7.24

Figure 7.25

Figure 7.26

Figure 7.27

Figure 7.28

Figure 7.29

Figure 7.30

Figure 7.31

Figure 7.32

Figure 7.33

Figure 7.34

Figure 7.35

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Chapter 1

Pages

i

ii

iii

iv

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

IEEE Press445 Hoes LanePiscataway, NJ 08854

IEEE Press Editorial BoardTariq Samad, Editor in Chief

Introduction to Magnetic Random-Access Memory

Edited by

Bernard DienyRonald B. GoldfarbKyung-Jin Lee

Copyright © 2017 by The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reservedPublished simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

ISBN: 978-1-119-00974-0

About the Editors

Bernard Dieny has conducted research in magnetism for 30 years. He played a key role in the pioneering work on spin-valves at IBM Almaden Research Center in 1990–1991. In 2001, he co-founded SPINTEC in Grenoble, France, a public research laboratory devoted to spin-electronic phenomena and components. Dieny is co-inventor of 70 patents and has co-authored more than 340 scientific publications. He received an outstanding achievement award from IBM in 1992 for the development of spin-valves, the European Descartes Prize for Research in 2006, and two Advanced Research Grants from the European Research Council in 2009 and 2015. He is co-founder of two companies, one dedicated to magnetic random-access memory, Crocus Technology, the other to the design of hybrid CMOS/magnetic circuits, EVADERIS. In 2011 he was elected Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

Ronald B. Goldfarb was leader of the Magnetics Group at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado, USA, from 2000 to 2015. He has published over 60 papers, book chapters, and encyclopedia articles in the areas of magnetic measurements, superconductor characterization, and instrumentation. In 2004 he was elected Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). From 1995 to 2004 he was editor-in-chief of IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. He is the founder and chief editor of IEEE Magnetics Letters, established in 2010. He received the IEEE Magnetics Society Distinguished Service Award in 2016.

Kyung-Jin Lee is a professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and an adjunct professor of the KU-KIST Graduate School of Converging Science and Technology, at Korea University. Before joining the university, he worked for Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology in the areas of magnetic recording and magnetic random-access memory. His current research is focused on understanding the underlying physics of current-induced magnetic excitations and exploring new spintronic devices based on spin-transfer torque. He is co-inventor of 20 patents and has more than 100 scientific publications in the areas of magnetic random-access memory, spin-transfer torque, and spin–orbit torque. He received an outstanding patent award from the Korea Patent Office in 2005 and an award for Excellent Research on Basic Science from the Korean government in 2010. In 2013 he was recognized by the National Academy of Engineering of Korea as a leading scientist in spintronics, “one of the top 100 technologies of the future.”

PrefaceA Perspective on Nonvolatile Magnetic Memory Technology

As context for this book, computer memory hierarchy ranges from cache (fastest and most expensive) to main memory, to mass storage (slowest and least expensive). Cache memory, immediately accessible by the central processing unit, is usually static random-access memory (SRAM). Main memory is usually dynamic random-access memory (DRAM); like SRAM, it requires power to maintain its memory state, but additionally must be electrically refreshed, typically every 64 ms (1). Mass storage is exemplified by nonvolatile flash memory (of the NAND and NOR varieties) and magnetic hard-disk drives.

Although magnetic random-access memory (MRAM), in particular spin-transfer torque MRAM (STT-MRAM), has the potential to serve as a universal computer memory—cache, main memory, and mass storage—it will likely be most cost-effective as main memory. MRAM is already a commercial product, albeit expensive and of low density relative to DRAM, and several variations of STT-MRAM are in development. Particular interest is in the superior performance of STT-MRAM with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Still under research are three-terminal spin–orbit torque MRAM (2,3), which has high endurance and separate paths for read and write current, and voltage-controlled magnetoelectric MRAM (4–7), which has low energy requirements.

More generally, MRAM, the subject of this book, is characterized by nonvolatility, low energy dissipation, high endurance (repeated writing), scalability to advanced (sub-20 nm) technology nodes, compatibility with complementary metal–oxide semiconductor (CMOS) processing, resistance to radiation damage, and short read and write times. The most intriguing of these, nonvolatility and low energy dissipation, are the main drivers of the technology.

Details of a 1024 bit core plane memory module (11). When magnetic-core memory was introduced in the mid-1950s, toroid cores were about 2 mm in outer diameter.

Nonvolatile MRAM is not really new. It was first developed in the early 1950s by Jay W. Forrester at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (8,9). As envisioned by Forrester, a three-dimensional magnetic-core memory module consisted of circumferentially magnetized toroids strung with x-, y-, and z-plane select wires and a fourth inductively driven output-signal wire. Switching times of the original material studied by Forrester, grain-oriented Ni50Fe50 “Deltamax,” were on the order of 10 ms. He noted that nonmetallic magnetic ferrites would switch in less than 1 μs based on materials research by William N. Papian (10), and that is how the technology developed. The estimated cost per bit was $1 ($9 today, adjusted for monetary inflation).

Another form of nonvolatile magnetic memory was developed by Andrew H. Bobeck and colleagues at Bell Laboratories in the late 1960s and early 1970s for mass storage: magnetic bubble memory (12,13). It was based on sequential, not random, access. Magnetic bubble domains in synthetic garnets with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy were stabilized by bias fields from permanent magnets. The presence or absence of a bubble—a logic “1” or “0”—was detected with magnetoresistive sensors. Bubbles could be generated, propagated, transferred, replicated, stored, and annihilated. Two orthogonal drive coils provided an in-plane rotating magnetic field to control the magnetization of Ni-Fe bubble-propagation elements (14).

The advent of DRAM in the 1970s, which sacrificed nonvolatility for reduced size, higher speed, and reduced cost, made core memory obsolete for main memory. By the early 1980s, storage density advances and cost reductions in hard-disk drives made bubble memory obsolete for mass storage (although bubble memory continued to be used in military and aerospace applications that required ruggedness).

Besides MRAM, other forms of nonvolatile memory are subjects of intense research. They are based on binary state variables that include “spin, phase, multipole orientation, mechanical position, polarity, orbital symmetry, magnetic flux quanta, molecular configuration, and other quantum states” (15). Mechanisms with great potential include resistive RAM (“memristors”) (16) and phase-change RAM (17). One of these may eventually become the dominant technology for cache memory, main memory, or mass storage, but for now, MRAM seems the most promising for main memory. Nevertheless, alternatives to MRAM should not be discounted (18,19).

Schematic diagram of the first commercial magnetic bubble memory module, TIB0103, manufactured in 1977 (14). Shown are the bias magnets, drive coils, control and interface circuits, bubble chip, and Ni-Fe “T-bar” bubble-propagation pattern. (An asymmetric chevron pattern was used instead in the TIB0203 in 1978.) The magnetic bubble diameter was 5 μm. The chip had 92,000 bits, a storage density of 155,000 bits/cm2, an access time of 2–4 ms, and a data transfer rate of 50,000 bits/s.

Coincident with the memory revolution is a rethinking of computer logic and architecture, particularly to address problems of energy consumption in supercomputers and massive data centers. For example, in the United States, the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) has sponsored the development of a prototype cryogenic computer under its “Cryogenic Computing Complexity” program (20). Dramatic reductions are projected in both energy consumption and size (21). Such a computer would combine superconducting, single flux quantum (SFQ) logic with hybrid superconducting/magnetic RAM. Hybrid superconducting/magnetic Josephson junctions switched by spin-transfer torque, resulting in measureable changes in critical current, have been demonstrated (22).

Recent accelerated growth in data centers and their demand for energy are bringing the need for new computer logic and memory to a head. World Wide Web search engines have resorted to storing most of their data in energy-inefficient DRAM (23) because retrieval from mass storage is too slow. There is a need to prototype, test, and benchmark (24) the energy dissipation, high-speed performance, reliability, dimensional scalability, temperature margins, and fabrication reproducibility of MRAM materials, devices, and circuits. Inevitably, new physical phenomena arise as nanostructures shrink in size, and failures will be determined by unknown variables and the increased relative importance of uncontrolled edge properties with respect to the bulk (25).

Nanopillar Josephson junction with a Ni0.8Fe0.2/Cu/Ni pseudo-spin valve (PSV) barrier (left) and voltage versus current at 4 K and zero applied field for parallel and antiparallel magnetic states (right) (22).

This book is designed for microelectronics engineers who need a working knowledge of magnetic memory devices. As conceived by one of the editors, Bernard Dieny, it aims to promote synergy between researchers and developers working in the field of electron devices and those in magnetics and information storage.

The chapters in this volume cover basic concepts in spin electronics (spintronics); magnetic properties of materials; micromagnetic modeling; dynamics of magnetic precession and damping; different implementations of MRAM; the integration of MRAM with CMOS; and future hybrid logic-in-memory architectures.

The authors are leaders in their respective fields. Nicolas Locatelli and Vincent Cros are known for their major contributions in the field of spin torque nano-oscillators and nanodevices assembled in novel computer architectures (26,27). Shinji Yuasa is noted for his pioneering experimental work (28,29) on giant magnetoresistance in magnetic tunnel junctions with MgO barriers (30,31). Liliana Buda-Prejbeanu is expert in micromagnetic modeling and computational magnetics (32). Bill Bailey is an authority on magnetization dynamics and spin–orbit coupling (33). Bernard Dieny is famous for his key role in the discovery of giant magnetoresistance in spin valve structures (34,35). Lucian Prejbeanu is known for his work on thermally assisted MRAM (36). Michael Gaidis is a microwave engineer who has specialized in “back-end-of-line” integration of MRAM with CMOS (37). The chapter on nonvolatile logic-in-memory (38,39) by Takahiro Hanyu, Hideo Ohno, and the team at Tohoku University represents one of the most complete compilations on this topical subject.

This book was sponsored by the IEEE Magnetics Society and published under the Wiley-IEEE Press imprint. The editor at Wiley-IEEE Press was Mary Hatcher.

Ronald B. Goldfarb

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Boulder, Colorado, USA

Note

The preface is a contribution of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, not subject to copyright.

References

1. I. Bhati, M.-T. Chang, Z. Chishti, S.-L. Lu, and B. Jacob, “DRAM refresh mechanisms, penalties, and trade-offs,”

IEEE Trans. Comput.

65, pp. 108–121 (2016); doi: 10.1109/TC.2015.2417540.

2. I. M. Miron, K. Garello, G. Gaudin, P.-J. Zermatten, M. V. Costache, S. Auffret, S. Bandiera, B. Rodmacq, A. Schuhl, and P. Gambardella, “Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection,”

Nature

476, pp. 189–194 (2011); doi: 10.1038/nature10309.

3. L.-Q. Liu, C.-F. Pai, Y. Li, H. W. Tseng, D. C. Ralph, and R. A. Buhrman, “Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum,”

Science

336, pp. 555–558 (2012); doi: 10.1126/science.1218197.

4. S. Kanai, M. Yamanouchi, S. Ikeda, Y. Nakatani, F. Matsukura, and H. Ohno, “Electric field-induced magnetization reversal in a perpendicular-anisotropy CoFeB-MgO magnetic tunnel junction,”

Appl. Phys. Lett.

101, 122403 (2012); doi: 10.1063/1.4753816.

5. W.-G. Wang, M. Li, S. Hageman, and C. L. Chien, “Electric-field-assisted switching in magnetic tunnel junctions,”

Nat. Mater.

11, pp. 64–68 (2012); doi: 10.1038/nmat3171.

6. Y. Shiota, T. Nozaki, F. Bonell, S. Murakami, T. Shinjo, and Y. Suzuki, “Induction of coherent magnetization switching in a few atomic layers of FeCo using voltage pulses,”

Nat. Mater.

11, pp. 39–43 (2012); doi: 10.1038/nmat3172.

7. P. K. Amiri, J. G. Alzate, X. Q. Cai, F. Ebrahimi, Q. Hu, K. Wong, C. Grèzes, H. Lee, G. Yu, X. Li, M. Akyol, Q. Shao, J. A. Katine, J. Langer, B. Ocker, and K. L. Wang, “Electric-field-controlled magnetoelectric RAM: progress, challenges, and scaling,”

IEEE Trans. Magn.

51, 3401507 (2015); doi: 10.1109/TMAG.2015.2443124.

8. J. W. Forrester, “Digital information in three dimensions using magnetic cores,”

J. Appl. Phys.

22, pp. 44–48 (1951); doi: 10.1063/1.1699817.

9. J. W. Forrester,“Multicoordinate digital information storage device,” U.S. Patent 2,736,880 (filed May 11, 1951, published February 28, 1956);

https://www.google.com/patents/US2736880

.

10. W. N. Papian, “A coincident-current magnetic memory cell for the storage of digital information,”

Proc. IRE

40, pp. 475–478 (1952); doi: 10.1109/JRPROC.1952.274045.

11. K. Lanzet, CC BY-SA 3.0;

http://wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7025574

(2009).

12. A. H. Bobeck, “Properties and device applications of magnetic domains in orthoferrites,”

Bell Syst. Tech. J.

46, pp. 1901–1925 (1967); doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1967.tb03177.x.

13. A. H. Bobeck and H. E. D. Scovil, “Magnetic bubbles,”

Sci. Am.

224 (6), pp. 78–90 (1971);

http://www.nature.com/scientificamerican/journal/v224/n6/pdf/scientificamerican0671-78.pdf

.

14. D. Toombs, “An update: CCD and bubble memories,”

IEEE Spectr

. 15 (4), pp. 22–30 (1978); doi: 10.1109/MSPEC.1978.6367665.

15. G. I. Bourianoff, P. A. Gargini, and D. E. Nikonov, “Research directions in beyond CMOS computing,”

Solid-State Electron

. 51, pp. 1426–1431 (2007); doi: 10.1016/j.sse.2007.09.018.

16. E. Gale, “TiO

2

-based memristors and ReRAM: materials, mechanisms and models (a review),”

Semicond. Sci. Technol.

29, 104004 (2014); doi: 10.1088/0268-1242/29/10/104004.

17. M. Wuttig and N. Yamada, “Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage,”

Nat. Mater.

6, pp. 824–832 (2007); doi: 10.1038/nmat2009.

18. Y. Fujisaki, “Current status of nonvolatile semiconductor memory technology,”

Jpn. J. Appl. Phys.

49, 100001 (2010); doi: 10.1143/JJAP.49.100001.

19. J. S. Meena, S. M. Sze, U. Chand, and T.-Y. Tseng, “Overview of emerging nonvolatile memory technologies,”

Nanoscale Res. Lett.

9, 526 (2014); doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-9-526.

20.Cryogenic Computing Complexity (C3) (2014),

http://www.iarpa.gov/index.php/research-programs/c3

(accessed Sept. 15, 2016).

21. D. S. Holmes, A. L. Ripple, and M. A. Manheimer, “Energy-efficient superconducting computing: power budgets and requirements,”

IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond.

23, 1701610 (2013); doi: 10.1109/TASC.2013.2244634.

22. B. Baek, W. H. Rippard, M. R. Pufall, S. P. Benz, S. E. Russek, H. Rogalla, and P. D. Dresselhaus, “Spin-transfer torque switching in nanopillar superconducting-magnetic hybrid Josephson junctions,”

Phys. Rev. Appl.

3, 011001 (2015); doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.3.011001.

23. J. Ousterhout, “The volatile future of storage,”

IEEE Spectr

. 52 (11), pp. 34 ff. (2015); doi: 10.1109/MSPEC.2015.7335899.

24. D. E. Nikonov and I. A. Young, “Benchmarking of beyond-CMOS exploratory devices for logic integrated circuits,”

IEEE J. Exploratory Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits

1, pp. 3–11 (2015); doi: 10.1109/JXCDC.2015.2418033.

25. H. T. Nembach, J. M. Shaw, T. J. Silva, W. L. Johnson, S. A. Kim, R. D. McMichael, and P. Kabos, “Effects of shape distortions and imperfections on mode frequencies and collective linewidths in nanomagnets,”

Phys. Rev. B

83, 094427 (2011); doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.83.094427.

26. N. Locatelli, V. Cros, and J. Grollier, “Spin-torque building blocks,”

Nat. Mater.

13, pp. 11–20 (2014); doi: 10.1038/NMAT3823.

27. N. Locatelli, V. V. Naletov, J. Grollier, G. de Loubens, V. Cros, C. Deranlot, C. Ulysse, G. Faini, O. Klein, and A. Fert, “Dynamics of two coupled vortices in a spin valve nanopillar excited by spin transfer torque,”

Appl. Phys. Lett.

98, 062501 (2011); doi: 10.1063/1.3553771.

28. S. Yuasa, T. Nagahama, A. Fukushima, Y. Suzuki, and K. Ando, “Giant room-temperature magnetoresistance in single-crystal Fe/MgO/Fe magnetic tunnel junctions,”

Nat. Mater.

3, pp. 868–871 (2004); doi: 10.1038/nmat1257.

29. S. Yuasa and D. D. Djayaprawira, “Giant tunnel magnetoresistance in magnetic tunnel junctions with a crystalline MgO(0 0 1) barrier,”

J. Phys. D Appl. Phys.

40, pp. R337–R354 (2007); doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/40/21/R01.

30. W. H. Butler, X.-G. Zhang, T. C. Schulthess, and J. M. MacLaren, “Spin-dependent tunneling conductance of Fe|MgO|Fe sandwiches,”

Phys. Rev. B

63, 054416 (2001); doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.63.054416.

31. S. S. P. Parkin, C. Kaiser, A. Panchula, P. M. Rice, B. Hughes, M. Samant, and S.-H. Yang, “Giant tunneling magnetoresistance at room temperature with MgO(1 0 0) tunnel barriers,”

Nat. Mater.

3, pp. 862–867 (2004); doi: 10.1038/nmat1256.

32. L. D. Buda, I. L. Prejbeanu, U. Ebels, and K. Ounadjela, “Micromagnetic simulations of magnetisation in circular cobalt dots,”

Comput. Mater. Sci.

24, pp. 181–185 (2002); doi: 10.1016/S0927-0256(02)00184-2.

33. W. E. Bailey, L. Cheng, D. J. Keavney, C. C. Kao, E. Vescovo, and D. S. Arena, “Precessional dynamics of elemental moments in a ferromagnetic alloy,”

Phys. Rev. B

70, 172403 (2004); doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.70.172403.

34. B. Dieny, V. S. Speriosu, S. S. P. Parkin, B. A. Gurney, D. R. Wilhoit, and D. Mauri, “Giant magnetoresistance in soft ferromagnetic multilayers,”

Phys. Rev. B

43, pp. 1297–1300 (1991); doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.43.1297.

35. B. Dieny, “Giant magnetoresistance in spin-valve multilayers,”

J. Magn. Magn. Mater.

136, pp. 335–359 (1994); doi: 10.1016/0304-8853(94)00356-4.

36. I. L. Prejbeanu, M. Kerekes, R. C. Sousa, H. Sibuet, O. Redon, B. Dieny, and J. P. Nozieres, “Thermally assisted MRAM,”

J. Phys Condens. Matter

19, 165218 (2007); doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/19/16/165218.

37. M. C. Gaidis, E. J. O'Sullivan, J. J. Nowak, Y. Lu, S. Kanakasabapathy, P. L. Trouilloud, D. C. Worledge, S. Assefa, K. R. Milkove, G. P. Wright, and W. J. Gallagher, “Two-level BEOL processing for rapid iteration in MRAM development,”

IBM J. Res. Dev.

50, pp. 41–54 (2006); doi: 10.1147/rd.501.0041.

38. S. Matsunaga, J. Hayakawa, S. Ikeda, K. Miura, H. Hasegawa, T. Endoh, H. Ohno, and T. Hanyu, “Fabrication of a nonvolatile full adder based on logic-in-memory architecture using magnetic tunnel junctions,”

Appl. Phys. Exp.

1, 091301 (2008); doi: 10.1143/APEX.1.091301.

39. T. Hanyu, D. Suzuki, N. Onizawa, S. Matsunaga, M. Natsui, and A. Mochizuki,“Spintronics-based nonvolatile logic-in-memory architecture towards an ultra-low-power VLSI computing paradigm,”

Proceedings of the Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference

(2015), pp. 1006–1011;

http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2757048

.

Chapter 1Basic Spintronic Transport Phenomena

Nicolas Locatelli1,2 and Vincent Cros2

1Unité Mixte de Physique, CNRS, Thales, Univ. Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, 91767 Palaiseau, France

2Centre de Nanosciences et de Nanotechnologies, CNRS, Univ. Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, 91405 Orsay France

Spintronics is a merger of magnetism and electronics. Conventional electronics uses only the charge of the electrons. For instance, transistors are based on the modulation of the density of electrons in a semiconductor channel by an electric field. Semiconductor-based memory (e.g., DRAM, Flash) stores information in the form of an amount of charge stored in a capacitor. In contrast, spintronics uses the spin of the electrons in addition to their charge to obtain new properties and use these properties in innovative devices. The spin of the electrons is an elementary magnetic moment carried by each electron. It has a quantum mechanical origin. Magnetic materials can be used as polarizers or analyzers for electron spins. This is why most spintronic devices combine magnetic and nonmagnetic materials, which can be metals, semiconductors, or insulators.

Magnetism has been used for a long time for data storage applications. Indeed, information can be stored in some magnetic materials in the form of a magnetization orientation. This was developed for storage on magnetic tapes as well as in magnetic hard disk drives (HDDs). The increase in the demand for storage capacity has stimulated an increase by eight orders of magnitude in the areal density of information stored in HDDs over the past 50 years; the bit area has decreased by the same factor. In 2014, bit sizes are typically on the order of 40 nm × 15 nm. This decrease in bit size has required continual improvements in the storage medium, in the write head used to switch the magnetization in the medium, and in the read head used to read out the magnetic state. This field of magnetic recording has benefited strongly from research and development in the field of spintronics. In particular, the discoveries of giant magnetoresistance in 1988 (1) and tunnel magnetoresistance at room temperature in 1995 (2,3) have been major breakthroughs from a scientific point of view, but they also helped recording technology keep moving forward. In 2010, a total of around 12,000 PB (1015 bytes) of storage capacity contained in 674.6 million HDDs were shipped worldwide.

Another type of spintronic devices that was proposed in the late 1990s is magnetic random-access memory (MRAM) (4). Indeed, solid state memory is of primary importance both for storage (the introduction of solid state drives in personal computers, tablets, and handheld devices) and for fast working memory between logic units and hard disk drives. In these applications, random-access memory based on devices involving magnetic materials, called magnetic tunnel junctions, are among the most promising technologies for future nonvolatile data storage, and may replace, in the near future, semiconductor-based memory (i.e., DRAM and SRAM), which represents a huge market.

This chapter is an introduction to the physical concepts required to understand how information is stored in a magnetic data cell, how this information can be detected, and how it is possible to modify the information by switching the magnetization from one state to another. First we introduce the basics of electronic transport in magnetic materials, a concept that is required for the comprehension of the physical mechanisms at the origin of magnetoresistive properties: giant magnetoresistance (GMR) and tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR), which is the magnetoresistive effect at play in spin-transfer torque (STT) MRAM devices. Then we describe how a spin-polarized current can exert a STT on the magnetizations in nanostructured spintronic devices by the interaction with local magnetic moments. Finally, we show how this novel effect can be used to modify the state of a magnetic element, leading to current-induced magnetization switching as the writing process in STT-MRAM.

1.1 Giant Magnetoresistance

After introducing the basic concepts of electronic transport in ferromagnetic metals, a simple model of the GMR effect is presented, the so-called “two-current model” that was proposed to describe the dependence of the electrical resistance of magnetic multilayered stacks on their magnetic configuration. This model is helpful for the understanding of the basic principles of spin-dependent transport. Finally, the main applications of GMR are discussed.

1.1.1 Basics of Electronic Transport in Magnetic Materials

Magnetism, as produced by magnetite (Fe3O4), has been known from at least ancient Greek times. It was described as a force, either attractive or repulsive, that can act at distance. The origin of this force is due to a magnetic field that is created by some materials (called magnets), or is induced by the motion of electrons, that is, electrical currents. In magnetic materials, such as iron (Fe) or cobalt (Co), sources of magnetization are mainly the electrons' intrinsic magnetic moment associated with spin angular momentum, or simply “spin,” and also to the electrons' orbital angular momentum. In Nature, other sources of magnetism are due to nuclear magnetic moments of the nuclei, typically thousands of times smaller than the electrons' magnetic moments. Consequently, these nuclear moments are negligible in the context of the magnetization of materials. However, they play an important role in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The spin magnetic moment and spin angular momentum are linked through the relationship , where g is a dimensionless number called the g-factor (or Landé factor) and is the Bohr magneton. In this expression, is the electron charge, is the electron mass, and is the reduced Planck constant. Due to the quantum mechanical nature of the spin, measurement of the projection of the electron spin on any direction can take only two values: +1/2 and −1/2.

In the context of spintronics, the main question is to understand how this fundamental characteristic property of the electrons, that is, the spin, influences the mobility of the electrons in materials. In fact, although it was suggested by N. Mott in 1936, the influence of spin on the transport properties in a ferromagnetic material was clearly demonstrated experimentally and described theoretically only in the late 1960s (for a review, see Ref. 5). The property of spin-dependent transport is at the heart of not only the GMR effect but also all related effects that have allowed the development of spintronic devices.

The ferromagnetic transition metals, such as Fe, Co, Ni, and their alloys, which are the key compounds in today's spintronic devices, have a specific electronic band structure compared to normal (nonmagnetic) metals. In transition metals, the two highest filled energy bands, which are the conduction bands, are occupied by 3d and 4s electrons. This nomenclature refers to atomic orbitals of the electrons. They are labeled s-orbital, p-orbital, d-orbital, and f-orbital referring to orbitals with angular momentum quantum number l = 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. These nomenclatures indicate the orbital shape and are used to describe the electron configuration. In a crystal, electrons with similar orbitals associate to fill a band of energy. More precise description on this topic can be found in any quantum mechanics textbook. In the case of ferromagnetic transition metals, each of these bands splits in two subbands corresponding to each spin configuration (see Fig. 1.1a). And in these magnetic materials, the interaction between spins, called the exchange interaction, energetically favors a parallel orientation of the electrons' spins.

Figure 1.1 (a) Schematic representation of the band structure of a transition metal with strong ferromagnetic properties such as Co or Ni. (b) Equivalent circuit for the two-spin subbands in the “two-current” model.

In the following, we will refer to electrons with a magnetic moment aligned parallel to the local magnetization as “spin-up” (↑) electrons, and to electrons with a magnetic moment aligned antiparallel to the local magnetization as “spin-down” (↓) electrons.

As for ferromagnetic metals, similar to a normal metal, the 4s band contains almost an equal number of spin-up and spin-down electrons. But the specificity of ferromagnetic metals lies in the structure of their 3d bands, for which the resulting lowest energy situation corresponds to a shift of the two subbands and (Fig. 1.1a). This offset generates an asymmetry for the number of electrons of each orientation, also responsible for the spontaneous magnetization. Consequently, they are also known as majority spin (↑) and minority spin (↓) electrons. It finally creates, for each spin orientation, a difference between spin-up and spin-down densities of states at the Fermi energy . We remind here that the density of states (DOS) D(E) of a system describes the number of states dn(E) per interval of energy dE around each energy level E that are available to be occupied by electrons: dn(E) = D(E)dE. The Fermi level EF corresponds to the highest energy level occupied by electrons in a system at a temperature T = 0 K. Electrons involved in the transport process lie at (or close to) the Fermi level.

In the low-temperature limit, one considers that the electron's spin is conserved during most scattering events. Under this assumption, transport properties associated with spin-up and spin-down electrons can be represented by two independent parallel conduction channels (Fig. 1.1b), and the mixing of these two conduction channels is then considered as negligible. In ferromagnetic metals, these two channels have different resistivities and , which depend on whether the electron magnetic moment is parallel (↑) or antiparallel (↓) to the direction of the local magnetization.

In a first, simple approximation, we can consider that 4s electrons, which are fully delocalized in the metal because they belong to outer electronic shells, constitute the conduction electrons that carry most of the current. In contrast, 3d electrons are more localized and responsible for the magnetic properties of the metal. The overlapping of s and d bands at the Fermi level allows current-carrying 4s electrons to be scattered on the localized 3d states, on the condition that they have the same energy and the same spin. The difference between the density of states of (↑) and (↓) 3d electrons at the Fermi level, therefore, results in different scattering probabilities for 4s electrons with spin (↑) or (↓).

In the case of Co and Ni, materials with strong magnetization, the bands are filled such that the Fermi level lies above the 3d↑ subband. This subband is then completely filled and the 3d↑ density of states at the Fermi level is zero (as illustrated in Fig. 1.1a). As a result, s → d electron scattering is possible only for s (↓) electrons, while (↑) electrons are not scattered on 3d states. This results in a much larger diffusion rate and thus a larger resistivity for the minority spin channel (↓) as compared to the majority spin channel (↑): . At low temperature and under this approximation of two independent channels, the total resistivity of a ferromagnetic metal is then given by the following simple expression (6):

At high temperatures, some additional scattering of conduction electrons, for instance, by spin waves (propagating perturbations in the magnetic materials), can cause spin-flip events, that is, a mixing of the two conduction channels, but those can be ignored in first approximation up to room temperature.

Two definitions for the spin asymmetry coefficient of a given ferromagnetic material are used in the literature, or . In strong ferromagnets such as Co or Ni, and thus .

A major consequence of the resistivity difference between conduction channels of minority and majority spin is that most of the current flows through the low resistivity spin (↑) channel. Consequently, an asymmetry in the current densities associated with (↑) and (↓) electrons appears. Hence, the current flowing in the ferromagnetic material is spin polarized. Calling j↑ and j↓ the current densities of spin (↑) and (↓) electrons, respectively, and the current spin polarization, p is defined by . Note that at low temperature.

1.1.2 A Simple Model to Describe GMR: The “Two-Current Model”

Historically, the two-current model, proposed by Mott and then by Fert and Campbell, was developed to explain the spin-dependent resistivity in materials doped with magnetic impurities. It allows the anticipation, in a rather simple way, of the GMR effect in magnetic multilayers. For this, we consider an archetypal multilayered stack consisting of thin layers of alternating ferromagnetic metals (F) and nonmagnetic (NM) metals. The magnetization of the ferromagnetic layers is supposed to be uniform within each layer. We also assume that the relative orientation of the magnetization in the successive F layers can somehow be changed from parallel (P) to antiparallel (AP) magnetic configuration, as illustrated in Fig. 1.3. The way this is achieved will be explained in more detail in the next section.

Two geometries to evaluate the resistance of this multilayered structure can be considered: either with current flowing parallel to the plane of the layers (known as “current-in-plane GMR,” CIP-GMR) or with current flowing in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the layers (known as “current-perpendicular-to-plane GMR,” CPP-GMR). The same model can be used to evaluate the magnetoresistive properties for both geometries, provided that the layers' thickness remains small compared to a characteristic length associated with each geometry.

For the CIP case, the characteristic length is actually the mean free path λ. For the CPP case, it is the spin-flip length or spin diffusion length lsf (7).

As illustrated in Fig. 1.2, during their Brownian motion throughout the structure with an average drift along the electrical field direction, the electrons traverse successive ferromagnetic layers. We denote the resistance associated with traversing a F layer for the majority spin channel (same direction as the magnetization) and the corresponding resistance for the minority spin channel (opposite direction to the magnetization), with . and are associated with the average resistance sensed by the electrons as they spend half of their total path, respectively, in the majority or minority spin channels. For the sake of simplicity, let us also assume that the resistance of the nonmagnetic separating layer is much smaller than r and R. Then, in the P configuration, spin (↑) and (↓) electrons behave, respectively, as majority and minority electrons in all magnetic layers. As a result, the respective resistances of the two spin channels are and . Since these two channels conduct the current in parallel, the equivalent resistance of the F/NM/F stack can be written as . In the case of materials with large spin asymmetry ( and ), the multilayer can be considered short-circuited by the spin (↑) channel; its equivalent resistance is .

Figure 1.2 Illustration of the two-current model. The conduction paths of spin-up and spin-down electrons in a ferromagnetic metal/normal metal/ferromagnetic metal (F/N/F) multilayer, in the two cases of CIP and CPP transport. Conduction electrons with spin magnetic moment aligned antiparallel (blue paths) to the local magnetization experience more scattering events than those with parallel spin (red paths). The equivalent resistance circuit is represented for the two magnetic configurations: parallel and antiparallel.

For the AP configuration, the electrons alternatively behave as majority or minority electrons as they propagate from one ferromagnetic layer to another. As a result, they are alternatively weakly and strongly scattered. Thus, the short-circuit effect previously mentioned in P configuration is here suppressed. In the AP configuration, the two channels have the same resistance . The F/NM/F equivalent resistance is then , which is, in general, much larger than .

Following this model, one can finally derive a simple expression for the amplitude of the GMR ratio:

Let us mention that another definition of the GMR ratio is sometimes used in the literature, notably in theoretical articles. It consists of normalizing the resistance variation between P and AP configurations by the resistance in the AP configuration: . In this definition, the GMR amplitude has a maximum value of 100%, whereas the commonly used definition often leads to magneto-resistive ratios over 100%. The GMR ratio is of prime importance for the characterization of the resistance variation, which is measured to determine the magnetic state of the stack.

1.1.3 Discovery of GMR and Early GMR Developments

The characteristic length scale of spin-dependent diffusion in thin films is on the order of a few nanometers in magnetic materials and tens of nanometers in nonmagnetic materials. These numbers explain why it took almost 20 years between the first basic studies on spin-dependent transport carried out on magnetic alloys in the late 1960s and the GMR discovery. GMR could be observed only in multilayered stacks consisting of nanometer thick layers. The growth of such multilayers became possible in the 1980s, thanks to the development of a new growth technique adapted from semiconductor industry: molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). GMR was actually discovered in magnetic metallic multilayers consisting of alternating layers of iron and chromium (Fe/Cr). This discovery by Albert Fert in Orsay, France, and Peter Grünberg in Jülich, Germany, in 1988, consisted of a very large variation in the CIP electrical resistance of these stacks under the application of an external magnetic field. Due to an antiferromagnetic coupling that exists between the successive Fe layers across the Cr spacers, the magnetization in the successive Fe layers spontaneously orient themselves in an AP configuration in zero magnetic field, as represented in Fig. 1.3. Upon application of a large enough magnetic field to overcome this antiferromagnetic coupling, the magnetization of all Fe layers can be saturated in the direction of the field, resulting in a P magnetic configuration. The GMR consists in a very large drop of resistance of 80% at 4 K (50% at 300 K) between the AP and P configurations. In 1988, it has been named “giant magnetoresistance” because the GMR amplitude was much larger than all known magnetoresistance effects at room temperature at that time. This discovery of GMR is considered the starting point of spinelectronics or spintronics. Almost immediately, GMR attracted enormous interest both from the point of view of fundamental physics and also for its possible applications, especially in the fields of data storage and magnetic field sensors. Fert and Grünberg were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2007 for this discovery.

Figure 1.3 Normalized resistance as a function of external magnetic field µ0H for Fe/Cr multilayers, with different Cr intermediate layer thicknesses. The magnetic configuration is AP at zero external field and P at large applied fields (positive or negative). (Adapted from Ref. 1 with permission from American Physical Society.)

Research on magnetic multilayers and GMR rapidly became a very active topic. It is not our aim here to provide an exhaustive review of all experimental and theoretical results that followed the initial discovery. A more complete review can be found in Ref. 6. Here we will rather introduce some of the key advances in GMR that occurred in the first years of spintronics.

Parkin et al. first demonstrated in 1990 the existence of GMR in multilayers prepared by sputtering (8), a simpler and faster physical vapor deposition (PVD) technique: a technique that is compatible with industrial processes. In magnetic multilayers consisting of alternating ferromagnetic and nonmagnetic layers, they also demonstrated the existence of oscillations in the FM interlayer coupling across the NM spacers as a function of the NM spacer thickness (see Chapter 2). This oscillatory coupling has been observed in a wide variety of multilayered systems, in particular (Fe/Cr) and (Co/Cu) multilayers. Another crucial step toward applications of GMR was also made in 1991 by Dieny et al., who developed trilayered ferromagnet/nonmagnetic metal/ferromagnet (F/NM/F) structures called spin valves, which exhibit GMR at low magnetic fields (a few millitesla instead of a few teslas for (Fe/Cr) multilayers (9). In these trilayers, the magnetization of one of the ferromagnetic layers is pinned in a fixed direction using a phenomenon called exchange bias, whereas the magnetization of the second ferromagnetic layer can be easily switched in the direction of the applied field. It is then possible to change the magnetic configuration of these spin valves from P to AP by applying a weak magnetic field (a few millitesla) parallel or antiparallel to the direction of magnetization of the pinned layer. These systems, which exhibit very high ‘resistance versus field’ sensitivity, were introduced as magnetoresistive heads in hard disk drives by IBM in 1998.

1.1.4 Main Applications of GMR

GMR has been primarily used as spin-valve magnetoresistive heads in HDDs between 1998 and 2004. It was subsequently replaced by TMR heads, which exhibit even larger magnetoresistance amplitude. GMR sensors are being used in other types of applications in the automotive industry, robotics, as three-dimensional position sensors, and sensors for biotechnological applications.

Some attempts have been made to use CIP-GMR for memory applications (MRAM), but only low-memory densities of about 1 Mbit per chip could be achieved. This memory is used mainly for space applications because of its radiation hardness (10).

1.2 Tunneling Magnetoresistance

The development of artificial magnetic systems based on magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs) was a second major breakthrough in spin electronics. Magnetic tunnel junctions look like spin valves from a magnetic point of view (two ferromagnetic layers separated by a nonmagnetic spacer) but a major difference is that the nonmagnetic spacer consists of a very thin insulating layer. In these junctions, the current flows perpendicular to the plane of the layers so that the electrons have to tunnel from one ferromagnetic layer to the other one across the thin insulating barrier.

After the pioneering work of Jullière (11) on Fe–GeO–Co junctions at 4.2 K in 1973, it was not until the mid-1990s that the improvement of both growth techniques and lithography processes allowed the fabrication of reliable MTJs. The devices studied used amorphous aluminum oxide (Al2O3) as the insulating barrier (2,3). They led to the first measurements of large magnetoresistive effects (TMR) with ratios on the order of 10–70% at room temperature. A great advantage of TMR with respect to GMR is the much larger impedance of MTJs compared to GMR metallic structures in the CPP geometry. Indeed, in MTJs, the resistance of the structure is effectively determined by the thickness of the tunnel barrier. MTJs can be patterned in the form of deeply submicrometer pillars with resistance ranging from kilohms to megohms, depending on the barrier thickness. This makes MTJs easier to integrate with CMOS components such as transistors, which have typical resistance in conducting mode of a few kilohms. In contrast, GMR submicrometer pillars in CPP geometry have resistances on the order of a few tens of ohms, which is fine for sensor applications, but difficult to integrate with CMOS components, in particular for MRAM applications.

An important research effort was undertaken on the materials side to improve the TMR amplitude. In 2004, it was discovered that much larger TMR ratios of about 250% at room temperature could be obtained in MTJs containing a monocrystalline magnesium oxide (MgO) barrier instead of an amorphous alumina barrier (12,13), reaching up to 600% at room temperature. These improvements have allowed a large increase of the sensitivity of magnetic HDD heads, which are needed for increased bit density. Thanks to their higher impedance than CPP-GMR devices, they also enabled new types of MRAM that could be scaled down in size and ramped up in density. Magnetic tunnel junctions are today the core elements of all MRAM technology (see Chapter 5).

As already mentioned, the transport mechanism across MTJs is no longer Ohmic transport as in GMR but relies on the well-known quantum mechanical tunneling effect. We start our second section by summarizing the basics of quantum mechanical tunneling. This will allow us to introduce Jullière's model for TMR, giving an intuitive explanation of the magnetoresistive effect in magnetic tunnel junctions. This introduction will be completed by a description of a more accurate model (Slonczewski's model), and the spin filtering effect. Lastly, the important matter of voltage dependence of TMR will be discussed.

1.2.1 Basics of Quantum Mechanical Tunneling

In classical physics, charge transport through an insulating layer (even if it is ultra-thin) is forbidden. Hence, tunnel conduction through a potential barrier is a pure quantum mechanical phenomenon, called the tunnel effect. This effect, predicted in the early years of quantum physics, now has important applications in semiconductor devices such as the tunnel diodes. It is extensively described in elementary textbooks on quantum mechanics: we will only summarize here the main points relevant to MTJ physics.

In Fig. 1.4, the potential landscape for a (injector) metal–insulator–metal (collector) junction is schematically depicted. The main characteristics of the insulating barrier are its energy height , and its thickness . We consider an electron with an energy , propagating in the metallic injector in the direction of the stack (perpendicular to the layers), with a wave vector amplitude , where is the electron effective mass and is the reduced Planck constant. Based on the free-electron approximation, the resolution of Schrödinger's equation demonstrates that the electron has a nonzero probability of propagating through the insulating barrier and inside the collector electrode. We recall that in the free electron approximation, it is considered that the electrons are not subjected to any confining potential inside the metal or the barrier. The only potential variation is due to the insulating barrier. This model is well suited to 4s electrons, which are delocalized in the crystal.

Figure 1.4 Schematics of the wave function of an electron tunneling between two metallic layers across a potential barrier.

Within the tunnel barrier, the electron wave function decays exponentially so that the probability for the electron to tunnel through the insulating barrier is given by

with the decay coefficient . A first conclusion from these expressions is that in order to limit the MTJ resistance with typically used materials (MgO, Al2O3), the thickness of the insulating layer has to be on the order of a nanometer, corresponding to a few atomic layers. As an illustration, considering that an electron has to cross a barrier, it would experience a decay length of .

In MTJs at zero bias voltage, the Fermi levels of the two electrodes align so that the same number of electrons are steadily tunneling from one side of the barrier to the other and vice versa. In order to obtain a net nonzero current flow, a bias voltage has to be applied between the two metallic electrodes. When a bias voltage V is applied, the collector electrode's Fermi level is lowered by relative to the injector's, so that electrons tunnel from injector to collector (see Fig. 1.4). The resulting current then depends on the barrier properties, but also on the states accessible on both sides of the barrier. Indeed, according to the Fermi's golden rule, the probability for an electron having an energy to tunnel through the barrier from metal 1 to metal 2 is proportional to the number of unoccupied electron states in 2 (collector) at this energy. In addition, the number of electrons that are candidates for tunneling is proportional to the number of occupied state in 1 (injector) at E. Therefore, the tunneling current from 1 to 2 due to electrons with energy can be written as

where and are the density of states (DOS), respectively, in electrode 1 at the energy and in electrode 2 at , and the functions and are the Fermi–Dirac distributions, which give the occupation probabilities of states in electrodes 1 and 2. Consequently, the product represents the probability, in electrode 1, of having an electron with the energy and the probability, in electrode 2, of having an unoccupied state at the energy . Finally, the term is the previously described transmission coefficient.

Using Eq. (1.4) to sum overall energies, the total tunneling current may be calculated. In the limit of zero temperature and small voltage V, it can be shown that only electrons at the Fermi level contribute to the current. The resulting conductance is then simply proportional to the product of the densities of states at the Fermi energy in the two electrodes:

1.2.2 First Approach to Tunnel Magnetoresistance: Jullière's Model

The simplified approach described in the previous section for deriving the amplitude of the tunneling current was used by Jullière in 1975 to analyze his pioneer results of tunnel magnetoresistance in a MTJ composed of two ferromagnetic thin films, iron (Fe) and cobalt (Co), separated by a thin GeO semiconducting layer (11). The ferromagnetic character of the electrodes was taken into account by introducing different densities of states for the majority and for the minority electrons, using the following definition for the spin polarization of a ferromagnet: