2,14 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Women Writers of the World

- Sprache: Englisch

Iphigenia is a compelling exploration of identity, societal constraints, and the struggles of self-discovery within the context of early 20th-century Venezuela. Teresa de la Parra critiques the expectations imposed on women and examines the conflict between personal desires and traditional values, portraying a young protagonist caught between duty and independence. Through the story of María Eugenia Alonso, the novel delves into themes of gender roles, class distinctions, and the limitations placed on women by family and social norms. Since its publication, Iphigenia has been recognized for its insightful psychological depth and its bold engagement with feminist themes. Its exploration of autonomy, the tension between modernity and tradition, and the sacrifices required for self-fulfillment have solidified its status as a significant work in Latin American literature. The novel's introspective narrative and rich portrayal of its protagonist continue to captivate readers, offering a timeless reflection on the challenges of forging one's own path. The novel's enduring relevance lies in its ability to illuminate the inner conflicts of individuals navigating societal expectations. By examining the intersections of personal aspirations and cultural constraints, Iphigenia invites readers to reflect on the broader implications of gender, class, and freedom in shaping one's destiny.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 796

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Teresa de la Parra

IPHIGENIA

Contents

INTRODUCTION

DEDICATION

IPHIGENIA

FIRST PART – A Very Long Letter Wherein Things Are Told As They Are in Novels

SECOND PART – Juliet's Balcony

THIRD PART – Toward the Port of Aulis

FOURTH PART – Iphigenia

INTRODUCTION

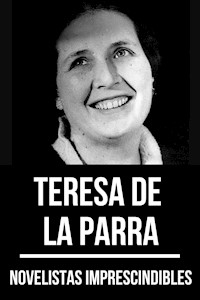

Teresa de la Parra

1889 – 1936

Ana Teresa de la Parra was a Venezuelan writer, widely recognized as one of the most significant literary figures of early 20th-century Latin America. Born in Paris to a Venezuelan family, she is best known for her novels that explore themes of identity, gender roles, and the constraints of society on women. Her works, though few in number, had a lasting impact on feminist thought and Latin American literature.

Early Life and Education

Teresa de la Parra was born as Ana Teresa Parra Sanojo into an aristocratic family. She spent her early childhood in Venezuela before moving to Europe for her education. Raised in a society with rigid gender norms, she was influenced by French and Spanish literary traditions, which later shaped her writing. Despite the constraints placed on women at the time, she developed a strong intellectual foundation and a critical perspective on the role of women in Latin American society.

Career and Contributions

Teresa de la Parra is best known for her two major novels: Ifigenia: Diary of a Young Lady Who Wrote Because She Was Bored (1924) and Memories of Mama Blanca (1929). Ifigenia, her most celebrated work, is a semi-autobiographical novel that critiques the oppressive roles imposed on women, portraying the struggles of a young woman caught between personal desires and societal expectations. The novel is considered a pioneering feminist work in Latin American literature.

Her second novel, Memories of Mama Blanca, presents a nostalgic and intimate view of Venezuelan aristocratic life, reflecting on childhood and the decline of the old social order. The book is noted for its poetic language and vivid storytelling, capturing a disappearing world with warmth and irony.

Impact and Legacy

Teresa de la Parra’s work challenged the traditional representations of women in Latin American literature, offering complex and independent female characters. Her novels were ahead of their time, engaging in discussions on gender, autonomy, and modernity that would gain prominence in later feminist movements.

She was also an influential intellectual figure, engaging in lectures and essays on women’s education and their place in society. Her ideas resonated with future generations of Latin American writers, particularly those advocating for women’s rights.

Teresa de la Parra died at the age of 46 in 1936, after suffering from tuberculosis. Despite her brief literary career, her works remain essential readings in Latin American literature. Today, she is regarded as a foundational figure in feminist literature in the region, and her novels continue to be studied for their rich psychological depth and social critique.

Her legacy endures through the powerful and insightful portrayals of women’s struggles, making her an enduring voice in the literary canon of Latin America.

About the work

Iphigenia is a compelling exploration of identity, societal constraints, and the struggles of self-discovery within the context of early 20th-century Venezuela. Teresa de la Parra critiques the expectations imposed on women and examines the conflict between personal desires and traditional values, portraying a young protagonist caught between duty and independence. Through the story of María Eugenia Alonso, the novel delves into themes of gender roles, class distinctions, and the limitations placed on women by family and social norms.

Since its publication, Iphigenia has been recognized for its insightful psychological depth and its bold engagement with feminist themes. Its exploration of autonomy, the tension between modernity and tradition, and the sacrifices required for self-fulfillment have solidified its status as a significant work in Latin American literature. The novel’s introspective narrative and rich portrayal of its protagonist continue to captivate readers, offering a timeless reflection on the challenges of forging one’s own path.

The novel’s enduring relevance lies in its ability to illuminate the inner conflicts of individuals navigating societal expectations. By examining the intersections of personal aspirations and cultural constraints, Iphigenia invites readers to reflect on the broader implications of gender, class, and freedom in shaping one’s destiny.

DEDICATION

To you, dear absent one, in whose shadow this book flowered little by little. To that clear light from your eyes that always lit the writing with hope, and also, to the white, cold peace of your two crossed hands that will never turn its pages, I dedicate this book.

Mother,

To you I dedicate this book which belongs to you, since it was from you that I learned to admire the spirit of sacrifice above all things. In its pages you will see yourself, Grandmother, Old Aunty, and Don Ramon himself, with all the attendant discussions against rebellious speech.

Learn from it how great a distance lies between what is said and what is done, so that you may never fear the arguments of revolutionaries, if they bear within their souls the mirror of example and the roots of tradition.

Close your eyes to one or another case of nudity; remember that you gave birth to all of us with very little clothing; you dressed us. Dress these pages too with white skirts of indulgence.

I embrace you with all my heart,

Ana Teresa

Paris, July, 1925

(Dedication Teresa de la Parra wrote in the copy of the first edition of Iphigenia that she gave to her mother.)

IPHIGENIA

FIRST PART – A Very Long Letter Wherein Things Are Told As They Are in Novels

From Maria Eugenia Alonso to Cristina de Iturbe

At last I’m writing to you, dear Cristina! I don’t know what you must have thought of me. When we said goodbye on the station platform in Biarritz, I remember that I, full of sorrow, sighs, and packages, told you while I hugged you, “I’ll write soon, soon, very soon!”

I was planning to write you a long letter from Paris and I had already started drafting it in my mind. However, since that memorable day, more than four months have gone by and except for postcards I haven’t written you a word. Have you at least received my last postcards? I ask because I didn’t mail them personally and I don’t know if the people I sent really mailed them.

Actually, I can’t tell you why I didn’t write from Paris, and much less why I didn’t write you later, when, radiant with optimism and looking like a very elegant Parisian, I was sailing for Venezuela on the transatlantic steamer Manuel Arnus. But, I will confess, because I know it all too well, that if I still haven’t written you from here, from Caracas, the city where I was born, even when time has weighed on me horribly, it was a pure and simple question of hurt and pride. I know how to lie very well when I talk, but I don’t know how to lie when I write, and since I didn’t want to tell you the truth for anything in the world, because it seemed very humiliating to me, I had decided to say nothing. But now I’ve decided that the truth to which I refer is not humiliating, but instead is picturesque, interesting, and somewhat medieval. Therefore, I have resolved to confess everything openly, trusting you are capable of hearing the pain that cries out in my words.

Oh, Cristina, Cristina, how bored I am! Look, no matter how you try you can’t imagine how bored I’ve been this past month, locked up in this house of Grandmother’s, which smells of jasmine, damp earth, wax candles, and Elliman’s Embrocation. The smell of wax comes from two candles, that Aunt Clara has burning continuously before a Jesus of Nazareth dressed in purple velvet, about a foot-and-a-half high, which since the remote days of my great-grandmother has been walking, carrying his cross, under a sort of glass dome or bell jar. The smell of Elliman’s Embrocation is due to Grandmother’s rheumatism, for she rubs it on every night before going to bed. As for the smell of jasmine and wet earth, which are the most pleasant of all, they come from the entrance patio, which is wide, square, and full of roses, palm trees, ferns, geraniums, and a huge jasmine vine that spreads out green and very thick on its wire arbor where it grows like a heaven full of jasmine stars. But oh! How bored I am breathing these odors singly or combined, while I watch Grandmother and Aunt Clara sew or I listen to them talk. It’s beyond explanation. Out of delicacy and tact, when I am with them I hide my boredom and then I chat; I laugh; and I show off the tricks of Chispita, the woolly lapdog, who has now learned to sit up with her two front paws bent very gracefully, and who, from what I have observed, in this system of imprisonment in which they are holding us both, constantly dreams of liberty and is as bored as I or even more so.

Naturally, Grandmother and Aunt Clara, who know how to distinguish very well the woven threads of fine drawnwork or lace, but who absolutely can’t see the things that are hidden behind appearances, have no idea of the cruel and stoic magnitude of my boredom.

Grandmother has this very false and out-of-date principle deeply rooted in her mind, “If people get bored it’s because they’re not intelligent.” And of course, as my intelligence constantly shines forth and it’s impossible to doubt it, Grandmother consequently deduces that I am amusing myself at all times in relation to my intellectual capacity, that is to say, very much. And I let her believe it for the sake of delicacy.

Oh! How many times I have thought in an acute crisis of boredom, “If I told Cristina this, it would relieve me so much.” But, for a whole month I have lived a prisoner to my pride as well as a prisoner within the four old walls of this house. I wanted you to imagine wonders about my present life, and, a recluse in my double prison, I was silent.

Today setting aside all pretense of pride, I’m writing to you because I can’t keep quiet any longer, and because, as I have told you, I have recently discovered that this situation of living walled in, as pretty as I am, far from being humiliating and vulgar, on the contrary, is like a tale of chivalry or the legend of a captive princess. And see, sitting now in front of this white sheet of paper, I feel so delighted with my decision, and my desire to write you is so, so great, that I could wish as the poem says “that the sea were ink and the beaches paper.”

But my immense need to write you has other causes also. One of them is, of course, my great affection for you; another is the dreadfully sad conviction that I will never see you again. As for the third, much more complicated than the other two, I will explain to you in words that will serve as an exordium or introduction to what I plan to write, because I don’t want this letter where I will pour out my heart to ever seem impromptu or ridiculous to you.

As you know, Cristina, I have always been quite fond of novels. You are, too, and I now believe that without a doubt it was our common interest in the theater and novels that caused us to become such close friends during the vacation months, just as during the school year a common interest in our studies drew us together.

You and I were obviously intellectual and romantic little girls, but we were also abnormally timid. Sometimes I’ve reflected on this feeling of timidity, and I now believe we must have acquired it by seeing our reflections in the glass of the windows and doors at school, with our wide foreheads, bare and framed by the black semicircle of our poor straight hair pulled back so tightly. As you will recall, this last requirement was indispensable, in the opinion of the Mothers, to the good name of the girls, who, besides being very tidy, were intelligent and studious as we two were. I became convinced that straight hair really constituted a great moral superiority, and yet, I always looked with great admiration at the other girls whose heads, “empty inside,” as the Mothers said, had on the outside that attractive appearance that came from the curls and waves they used in defiance of all the rules. In spite of our mental superiority, I remember that I always basically felt very inferior to the ones with loose hair. Heroines in novels also were placed in this group of girls with their temples covered, which clearly constituted what the Mothers called with great disdain “the world.” We, together with the Mothers, the chaplain, the twelve daughters of Mary, the saints of the Christian year, incense, chasubles, and prayer benches, belonged to the other group. In reality I never had true partisan enthusiasm. That wicked “world” so abhorred and despised by the Mothers, in spite of its vile inferiority, always appeared dazzling and full of prestige in my eyes. Our moral superiority was a kind of burden to me, and I recall that I always bore it filled with resignation; thinking sadly that, thanks to it, I would never perform anything except obscure and secondary roles in life.

What I want to explain to you is that in these four months I have completely altered my ideas. I think I have switched bag and baggage to the abominable band of the world and I feel that I have acquired an elevated rank in it. I no longer consider myself a secondary character at all. I am quite satisfied with myself, and I have declared myself on strike against shyness and humility; I have, moreover, the presumption to believe that I am worth a million times more than all the heroines in the novels we used to read in the summer — novels which, by the way, must have been very poorly written.

In these four months, Cristina, I have lived through many periods of sadness, I have had some disagreeable impressions, some revelations that caused despair, and, nonetheless, in spite of everything, I feel an immense joy because I have seen a new personality emerging in myself that I didn’t suspect and that fills me with satisfaction. You and I — all of us who, moving through the world, have some talents and some sorrows — are heroes and heroines in the novels of our own lives, which is nicer and a thousand times better than written novels.

It is this thesis that I am going to develop before your eyes, relating to you in minute detail and as they do in authentic novels, everything that has happened to me since you disappeared from view in Biarritz. I’m sure that my story will interest you greatly. Besides, I have lately discovered that I have a gift for observation and great ease in expressing myself. Unfortunately these gifts have been worthless to me up to the present. Sometimes I have tried to demonstrate them to Aunt Clara and Grandmother, but they can’t appreciate them. Aunt Clara hasn’t even taken the trouble to notice them. As for Grandmother, since she’s very old she has some terribly old-fashioned ideas; and yes, she has noticed my abilities, because twice she’s told me that my head is full of bugs. As you can understand, this is one of the reasons why I’m bored in this big, dreary house, where no one admires or understands me, and it is my need to feel understood that decidedly has spurred me to write you.

I know very well that you will understand me. I feel no reserve or embarrassment at all in sharing my most intimate confidences with you. In my eyes you have the sweet prestige of a past that will never return. Any secrets I may tell you can have no disagreeable consequences in my future life and, therefore, I already know that I’ll never repent having told them to you. Yes, in our future they will be like the secrets that are buried with the dead. As for the very great affection that it takes to write you my secrets, I think that it is rather like the tardy flowering of tenderness, when we think about those who have gone, “never to return.”

***

I’m writing in my room whose double doors I’ve locked. My room is big and bright, its wallpaper is sky blue, and it has a window with bars that faces the second patio of the house. Outside the window, right up against the bars, there is an orange tree, and beyond, at each corner of the patio, there are other orange trees. Since I have placed my desk and my chair very close to the window, while I think with my head reclining against the back of the chair, or leaning my elbows on the white surface of the desk, I am always looking at my patio with the orange trees. And I have thought so much, gazing up, that I now know even the tiniest detail of the green filigree against the blue sky.

Now, before starting my story, without looking at orange trees, or sky, or anything, I’ve closed my eyes for an instant, I have locked my hands over them, and very clearly, for a few seconds, I’ve seen you again, just as you were when you faded in the distance there, on the station platform in Biarritz: first walking, then running beside the window of my coach as it moved away, and then your hand, and finally your handkerchief, which was waving to me: Goodbye! . . . Goodbye! . . .

Oh, that handkerchief that waved goodbye, Cristina! Its whiteness has remained eternally imprinted in our minds, as if to help us weep for these painful and definitive separations! . . .

I remember very well that when I could no longer see you, I moved back from the window, and that way, at a distance, I stood still awhile watching the accelerated racing of the houses and posts, which I finally turned my back on; I then sat down on the seat, and I saw a mirror in front of me in the coach, and I saw my poor little face so sad, so pale, swathed in the black of mourning, so that I was intensely conscious for the first time of how alone I was. I remembered girls in orphanages and I seemed to see myself as a symbol of the orphan. Then I had a moment of anguish, a kind of horrible choking, feeling that I wanted to burst out in sobs and pour a torrent of tears from my eyes. But suddenly I looked at Madame Jourdan — do you remember Madame Jourdan? She was that distinguished lady, with gray hair, who at the hotel had the table next to ours and who then took charge of accompanying me to Paris. Well, I looked at Madame Jourdan out of the corner of my eye. She was sitting at the far end of the coach, and I saw that she was studying me with curiosity and pity. As I realized this I suddenly reacted and the storm dissipated. And at that moment, as now, as always, I am more or less the same as when you knew me. I never cry in spite of having every reason to cry oceans. Maybe because sorrow always hovers over me, I have learned to hide it from everyone, with an instinctive reaction, as some poor children hide their worn shoes from people who are rich and well dressed.

Fortunately, Madame Jourdan, who turned out to be a charming person, managed, little by little, to distract my sadness with her conversation. She began by asking me about you. At first, seeing us always together and speaking Spanish, she had taken us for sisters. Then when they told her about Papa’s sudden death and asked her if she would like to chaperone me to Paris, she began to take a very lively interest in me. She had lost a little girl, her only daughter, and the child, then five years old, would now have been about our age. She asked me how old I was. When I told her that I had just turned eighteen, she answered, breaking her phrases with heartfelt sighs, “The world is a puzzle with no solution! . . . The pieces are scattered and no one can fit them together! ... I am entering the desert of my old age so alone, because I lost my daughter, and you are marching into that great battle of youth without the support and shelter of your Mother! ...”

That part about the “desert of her old age” and about “the great battle of youth” she said in such a beautiful way and with such a soft and harmonious voice, that I suddenly started feeling great admiration for her. I remembered the actresses who filled both you and me with an almost frenetic enthusiasm because of their commanding voices and the grace of their movements. I thought Madame Jourdan must be like them, that without a doubt she was very intelligent, that perhaps she might be an artist, one of those novelists who write under a pseudonym. Abandoning my seat and my window, impelled by the most lively and reverent admiration, I went to sit next to her.

At first and in view of her superiority, I felt somewhat timid, somewhat inhibited, but I began to talk to her, and then I told her that I was going on a long trip, that I was coming to America where I had my maternal grandmother and some aunts and uncles and cousins who loved me very much. Then we chatted about travel, about different climates, about the beauty of nature in the tropics, about the gaiety of life aboard a transatlantic steamer, and within two hours, my earlier timidity now forgotten, Madame Jourdan and I were such friends and we got along so well, that it seemed to me I had fitted together some of my personal puzzle. Believe me, Cristina, and this, of course, I wouldn’t want Grandmother to know, I would willingly have stayed there to live forever with that delightful Madame Jourdan!

But unfortunately the trip ended, the time came when we reached Paris and then she had to deposit me with my new chaperons, Mr. and Mrs. Ramirez, who were a Venezuelan couple and close friends of my family; definitively checked into their hands, I was left in their care as far as La Guaira.

I immediately liked the Ramirezes because they were happy, obliging, kind, and because they had the admirable custom of never giving me any kind of advice. This latter is quite a rare thing, since generally, as you, too, must have noticed, it is through this system of advice that those superior in age, dignity, or government are in the habit of venting their bad temper, telling us, poor inferiors, the harshest and most unpleasant things in the world.

Mr. and Mrs. Ramirez lived in a very elegant hotel. When I arrived in the company of Madame Jourdan, they came out to receive me affectionately and attentively. After the prescribed introductions, they started out by expressing their sympathy for my situation, something which apparently is de rigueur when dealing with me. Then they talked to me about Caracas, about my family, about our coming trip, and they ended by turning over to me about twenty thousand francs, sent by my uncle and guardian to cover expenses of my toilette and pocket money, they supposed, since the money for the travel expenses had already been sent.

Well, you may call me mercenary if you like, but I can’t deny that with that unexpected twenty thousand francs, the gloomy thoughts I’d had on the train went flying away like a flock of swallows, because I judged myself fortunate and independent.

Moreover, Mr. Ramirez, who had lived in New York for many years, told me that during the time we were to remain in Paris, he saw no reason why I shouldn’t go out alone, unless, of course, his wife and I happened to be going the same way.

Naturally I decided right then not ever to be going the same way as Mrs. Ramirez, and here, as you will see, my experiences, impressions, and adventures begin.

You don’t know how interesting it is to travel, Cristina! Not short trips on the train, like those you and I used to take in the summer during the vacation months; no, I mean long trips, like this one of mine, when you can go out alone in Paris, and you meet a lot of people, and you cross the ocean, and you stop at different ports. The only bad part about these trips is that, as with all trips, one must arrive eventually, and when you arrive — oh, Cristina, when you arrive it is like when the coach you were riding in stops or when the music that was lulling you to sleep fades into silence. How sad it is to arrive anywhere forever! ... I think it must be for that reason that death frightens us, don’t you agree?

Going back to my first meeting with Mr. and Mrs. Ramirez, I must tell you that since the day Papa died it hadn’t occurred to me that I was what might be called an independent person, more or less mistress of myself and of my actions. Up until then I had considered myself something like an object that people pass about, lend or sell to each other. That is what we young ladies of “proper upbringing” generally and sadly are! And that is what I have become again here in Caracas.

It was Mr. Ramirez with the twenty thousand francs, and the permission to go out alone, who suddenly revealed to me that delicious sensation of liberty. I recall that the very night of my arrival in Paris, I was sitting alone in the hotel lobby, facing a group of people who, at a distance from me, were talking among themselves. Overflowing with optimism and with a certain prophetic spirit, I began to fully savor my future liberty. Isolated as I was before the happy and animated scene, I gazed at myself for a long time in a mirror, as I often do, and I suddenly observed that, without your support and without your company, my schoolgirl simplicity or air of a timid miss looked horribly conspicuous, awkward, and ridiculous. I said to myself that with twenty thousand francs and a little ingenuity it was possible to do a lot. Then I thought that I might well leave my whole family in Caracas epate with my Parisian elegance. I finally deduced that in order to do so it was indispensable to wear more formfitting dresses and to cut my hair a la gargonne, just like a certain lady who at that moment stood out in the group in front of me because of her very lovely figure.

And without further hesitation, my mind was made up.

The following day, very early in the morning, I went to buy some flowers and with them in my hand I went to the home of my dear friend from the train, Madame Jourdan. She received me warmly, as if we had known each other all our lives and as if it had been a century since we’d seen each other. She had an adorable house, decorated with exquisite taste, which contributed to the fact that my admiration and appreciation continued growing en crescendo. I explained to her that I had decided to cut my hair, because I intended to return to my country as a truly chic and stylish person. She was very amiable and helpful, and started giving me advice about my toilette and about tasteful style. She recommended dressmakers, milliners, hairdressers, manicurists, and a multitude of other things. She offered to help me in all kinds of ways in the future, too, and under her direction I began my campaign that very afternoon.

Then I wish you could have seen what excitement — all the coming and going — what days I spent! And above all, what a change! I no longer had that droopy schoolgirl air, like a Men fouette, don’t you know? I looked wonderful with short hair. The dressmakers thought I had a marvelous figure, very willowy, and as I tried on clothes, they constantly said, “Comme Mademoiselle est bien faite!”

That was something I verified instantly, turning in every direction in front of the three-way mirrors, causing me an infinitely greater satisfaction than the cross for the week, the ribbon or the first place in composition, and all of that great reputation for intelligence which you and I shared in our classes.

Once I fell in love with a black toque that the milliner told me was only worn by widows, and that seemed charming to me. Within a few days, 1 was going about wearing my toque with its long black veil. They called me “Madame” in the stores, and one day when I went to a shoe store with the youngest of the Ramirezes’ children, a darling three-year-old, someone said I must have married very young to have that adorable child who looked just like me. If that were true, I began figuring that given Luisito Ramirez’s age he would have been born when you and I were in the tenth grade. Imagine how the nuns would have been scandalized and how much fun we would have had with a little tot then. Surely we would have been forced to hide him in our desks as we used to do with boxes of candy.

But certainly then, with my toque and my assumed widowhood, Paris seemed something new and unknown to me. It was no longer that foggy, cold city where, on Christmas vacations, you and I would trudge, holding hands and followed by our English governess while we trotted to matinees at the Opera or the French Theater. Everything used to intimidate me then. Elegant ladies gave me a feeling of fear and I felt so little, so mousey, beside such beauty and such luxury. Now I didn’t; now I had been touched by the magic wand; I moved easily, surely, and very gracefully, because I knew all too well that that “Comme Mademoiselle est bien faite!” was being expressed loudly and with exclamation marks by the eyes of everyone who looked at me. It was such a general phenomenon that I was enchanted. Everybody admired me. My friends Mr. and Mrs. Ramirez admired me; their children admired me; some very nice Spaniards who had the table facing ours in the dining room admired me. Others who admired me were the hotel manager, the waiter at our table, the elevator boy, the manicurist’s husband, the clerks at the hairdressing salon, and a very elegant gentleman I saw one morning on the street who said to his companion as he saw me approach, “Regardez done, quelle jolie fille!”

Decidedly, in those glorious days, Paris suddenly opened her arms and received me as her daughter, just like that, all at once, just because. Oh! It was unquestionable! I now formed a part of that troop of women whom Papa used to evoke, half-closing his eyes with a strange expression which I couldn’t quite understand then, because it was as if he were talking about some very rich sweet, as he said, “What women!!”

Nothing like that had ever happened to me, Cristina. I felt a wild joy within myself. It seemed to me that my soul had burst into bloom like those trees in the school park in the months of April and May. It was as if I had suddenly discovered a mine in myself, a spring bubbling with optimism and I lived only to drink from it and to see my reflection in it. I believe that it was because of that selfish satisfaction that I never wrote to you, except for laconic postcards that you answered with inexpressive, sad letters. Today, as I reread them, they seem to communicate all your bitter disillusionment and I am contrite. But I think by now you must have understood the reason for my indifference, which was as fleeting as my joy and I think that you generously must have forgiven me for both.

Sometimes, too, I would think that the optimism and joy of life that made me so happy were improper so soon after a recent bereavement like mine. Then I would suffer periods of sharp remorse, and to quiet my guilt and apologize to Papa’s spirit, I would give a few francs to some ragged child or go in and leave an offering in the charity box of a church . . .

Oh, Papa! Poor Papa! There, in the gentle visions of my mind, I see your indulgent face, beautified by the approving indulgence of your smile. How well I recognize it! . . . Yes, how could my happiness anger you! Those brief days, when your prodigal and jovial spirit seemed to be reborn for a moment in my soul, were the only inheritance that you were to bequeath me! . . .

We stayed in Paris for almost three months, due to a delay in funds and a change of the Ramirezes’ plans. The days, which individually raced by with dizzying speed, put together, seemed many and very long. I felt that they were slipping through my fingers and I had the feeling that I was running after them to hold them back. I was very preoccupied by the idea of leaving; I thought sadly that some day it would be necessary to abandon the Paris which was showing itself so kind to me, so affectionate, just as I had to abandon you, Madame Jourdan, everything I have loved and that has loved me in this life. “What a calamity! What a great misfortune!” I thought continually. And this prospect was the only thing that embittered my happy life, free as a bird whose wings have feathered at last.

But as everything comes to pass in this world, a sad day came when Mr. and Mrs. Ramirez and I finally had to pack our trunks. I put on the new travel dress I had chosen with the utmost care for the best possible cut and the greatest elegance. Holding my necessaire in my hand, I strolled awhile in front of the biggest mirror in the hotel and thus verified that I looked like a very chic traveler. Then, with Mr. and Mrs. Ramirez, I took the train to Barcelona, where the transatlantic steamer Manuel Arnus was to take us to La Guaira.

I remember that before embarking I sent a goodbye hug to you on a postcard. I didn’t write more than that because I was overwhelmed with melancholy and because I had to go buy a bottle of Guerlain liquid rouge, which they had just recommended to me highly for its ability to withstand the violent sea air that erases all powdered rouge from your skin.

Then we sailed.

Oh! My ears still seem to hear that shrill siren as the ship moved out and I get so sad when I evoke the memory that I prefer not to talk about this.

Fortunately life on board soon distracted me. It’s a delicious sensation to be on the high seas, surrounded on all sides by the heavens and on your way to America. One thinks of Christopher Columbus, the novels of Jules Verne, desert islands, and mountains beneath the sea; it makes you want to be shipwrecked and to have adventures. But this geographical part is soon forgotten when you begin to enter fully into the very interesting social atmosphere on board. Well, as you know, I am not in the habit of praising myself because it seems in bad taste to me, but notwithstanding, I can’t deny that from the time I boarded the ship I was aware that I was causing a great sensation among my traveling companions. Nearly all the ladies lay seasick on their deck chairs or locked in their cabins. I, who had not been seasick for a second, did nothing except parade my repertory of wraps, dresses, and gauzy shawls that I learned to tie very gracefully around my head, under the pretext of protecting it from the wind. They were my specialty: I wore a black and white one in the morning, a lilac one at noon, a gray one at night, and I strolled up and down with a book or a bottle of salts in my hand, with all the poise, grace, and distinction acquired during the days of my Parisian life and which you still have not seen me exhibit.

The men, sitting on deck, with wool berets pulled down to their ears and a cigar or cigarette in their mouths, would instantly lift their eyes from the book or magazine they were absorbed in as they saw me go by, and they would follow me awhile with a long stare full of interest. The women on the other hand admired my chic clothes and looked at them with some curiosity, I think also with some envy and as if they would like to copy them. I cant conceal from you that all this interest flattered me greatly. Didn’t it represent charming success, something that until then had been as distant, fabulous, and dazzling as a sun? I felt, therefore, extremely happy to confirm that I possessed such a treasure, and I confess this to you without any sort of hesitation or modesty, because I know very well that you, sooner or later — when you give up long hair, begin wearing Louis XV heels, use rouge and, above all, lipstick — will experience this, too, and therefore you aren’t going to listen to me with the profound scorn of people incapable of understanding these things, such as Grandmother, the Mothers at school, and Saint Jerome, who, apparently, wrote horrors about the chic woman of his day.

After the first few hours of the crossing, I soon began to find friends besides my escorts, Mr. and Mrs. Ramirez. They were an Andalusian couple with a darling little boy who adored me; a Peruvian family; the Captain, who was very nice; the Doctor; the Purser; and naturally the small group of Venezuelans who along with us were going to La Guaira.

But the most interesting of my friends turned out to be a Colombian poet, a former diplomat, a widower, a bit old, who, full of gallantry, courtesy, and enthusiasm, accompanied me continually. At night, when they were playing or singing in the ballroom, I, considering my mourning, would avoid the merriment and would seek out some solitary spot on deck, and there, lulled by the music and with my elbows on the rail, would contemplate the fantastic reflection of the moon on the tranquil sea and the white wake we were marking on the dark blue waters. My friend, who was sensitive enough to always notice my absence, would appear beside me in a few minutes, rest his elbows too on the rail, and then softly, with a monotonous hissing of s’s, would recite his verses to me. This delighted me. Not because his verses were so pretty, since to tell the truth I never paid the least attention to them, but because, being free from all conversation while he recited, I could fully yield to my own thoughts and I would say to myself, “There is no doubt that he is very much in love with me.” And since it was the first time this had happened to me and since the beauty of the night lent itself so well to this, I gave free rein to my memories of those novels from La Mode Illustree that you and I used to read on vacation. I immediately compared myself to the novels’ most interesting heroines; I considered myself on the same level with them or perhaps even higher; and naturally, I was so satisfied with such a vision that, when my friend would finish the last line of his poem, I would praise it passionately with the most enthusiastic and sincere admiration.

If the relationship between my friend and me had never gone beyond that, everything would have been fine. He would have acquired everlasting prestige in my eyes, and after we parted, I would have seen him forever in the mist of my memories, fading there, in the distance, beside the sea and the moon like a sweet dream of romance and melancholy. But, unfortunately, Cristina, men have no tact. Even if they are wiser than Solomon and older than Methuselah, they never learn that simple, easy, and elementary thing called “tact.” I learned this dealing with my friend the poet/ex-diplomat on the ship, who, apparently, was very well educated, intelligent, and discreet in any subject except this matter of tact, or knowing what is fitting. But I will relate the incident from which this judgment or experience arises so that you may form your own opinion.

Imagine, one night when some national holiday or other was celebrated on board, all the passengers had drunk champagne and were therefore feeling quite happy. On the contrary, I was in a bad mood, because as I was pinning on a brooch I had torn a long scratch on my left hand, leaving it quite disfigured. Consequently, that night, with more justification than usual, while the others were amusing themselves in the ballroom, I went to lean against the rail at my solitary place on deck, and also, as usual, my friend soon came to join me. Due to my bad mood, contemplating the ocean lit by the moon, I was angrily calculating the number of days the scratch would remain on my hand and I didn’t say a word. My friend, then, showing a certain delicacy, instead of throwing himself into a recitation of his poetry, questioned me gently, “What’s the matter with you tonight, Mana Eugenia? You seem so sad.”

“It’s just that I scratched my left hand, and it hurts me a lot.”

And since it has always seemed best to me frankly to show those physical defects which, because they are visible, cannot be hidden, I showed him my left hand with a very long red line crossing it diagonally.

He, in order to examine the scratch up close, took my hand between his hands and after saying that the wound was slight and almost imperceptible he continued gazing at the hand and added softly with the voice he used to recite, “Oh! What a divine hand! Like an Italian madonna! It might be carved in ivory by the zeal of some great Renaissance artist to awaken the faith of unbelievers. If, when I visited the Carthusian convent in Florence a year ago, I had seen a virgin with hands like these, I would have taken my vows!”

As you know, Cristina, my hands, really, aren’t bad; and as you also will recall, I have always been very proud of them. The change of temperature had given them a pale tone, so that at that moment, ennobled by the moon, polished and groomed, in spite of the scratch on the left one, in truth, they deserved that praise, which, besides seeming precise, also seemed to me delicate, well chosen, and in very good taste. And in order to show off my hands even better, my vexation partly gone, I propped my elbows back on the rail, joined my hands in a languid posture, gently rested my chin on them, and continued gazing at the ocean.

“Now they look like two lilies holding a rose,” my friend recited again. “Tell me, Maria Eugenia, haven’t your cheeks ever been jealous of your hands?”

“No,” I responded. “Everyone here lives in perfect harmony.”

And because it seemed appropriate to give such a brief phrase some expression, without changing my pose, I half closed my eyes. With my eyes slightly narrowed, I gave my friend a long look and I smiled.

But, unluckily, as our amicable dialogue reached this point, Cristina, guess what suddenly occurred to my friend the poet! Well, it occurred to him that his ugly, ugly mouth, with his gray mustache, smelling of tobacco and champagne, might kiss mine, which at that moment was smiling, fresh, and just painted with Guerlain lipstick. Oh! But, happily, as you know, I am agile and quick to react, and thanks to that such a disagreeable plan could not be carried out; because when I suddenly felt myself imprisoned in his arms, I was overcome by fear produced by the surprise itself, and nervously moving my head in every direction, I managed to slip to one side and hurriedly escaped. Once at a distance, out of curiosity, I turned to see how this singular scene had ended, and I realized that the violent movement of my head combined with my brusque escape, had knocked the glasses off my friend’s nose. He was very myopic, and therefore at that critical moment, to the pain of defeat and the pain of scorn was added the dark pain of blindness.

Oh! Cristina, no matter how long I may live, I’ll never forget that short figure, in confusion, unseeing, bending over toward the deck, hopelessly searching for his lost glasses, which, from a distance, I could see gleaming quite near his feet.

From that night on I didn’t speak to my great admirer and friend the Colombian poet. Not because I really felt very offended, but because after what had happened it seemed mandatory to adopt a suitable, silent, and enigmatic attitude. Certainly, locked up in my distinction and rancor, life on board ship was much less fun for me. I no longer had anyone to show his admiration for me in a gallant whisper; nor to laugh at my wit; nor to recite poetry to me in the moonlight; nor to shower me with kind attention. When I went on deck with my filmy scarf tied on my head, I sought solitude, and I stayed a long time on a high bridge sitting, facing the sea, contemplating with melancholy the persevering progress of the ship and thinking from time to time that my friend had committed that great gaffe because he had a somewhat mistaken idea about his personal appeal. I told myself that, without a doubt, he had never realized that I found his nose too big, that I thought him poorly proportioned, too old, too thin, and that relative to his poetry, the only thing I had ever appreciated about it was its monotonous rhythm that allowed my own thoughts to flow.

From that, Cristina, I deduced that men, in general, although they may appear to know a lot, it is as if they knew nothing, because, since they do not have the ability to see their own image reflected in someone’s spirit, they are as totally ignorant of themselves as if they had never looked in a mirror. For that reason, when Grandmother, at the table, speaks indignantly of men today and warns me against them, calling them boastful and liars, I, far from sharing her indignation, recall my friend the poet at the moment he lost his glasses, and I smile. Yes, Cristina, no matter what Grandmother says, I think men lie in good faith, that they are braggarts because they honestly don’t know themselves, and that they go through life happy and surrounded by a pious halo of error, while ridicule escorts them in silence like a faithful and invisible dog.

After sailing for eighteen days, one calm evening, at nightfall, under the half-light of the most unbelievable sunset, we entered Venezuelan waters at last.

Feeling sentimental and emotional when I heard the news, I went off to sit on my solitary bridge so that I could feel and see from above the triumphant spectacle of reaching land while hidden from everyone.

I will always remember that evening.

There are instants in life, Cristina, when our being seems to completely dematerialize, and we feel it rise exalted and sublime within us, like a visionary who speaks to us of unknown things. Then we experience a holy resignation in the face of future grief, and we also feel in our souls the flowering of past joys, much sadder than our sorrows, because in our memory they are like dead bodies that we can never decide to give up. Surely you, too, have experienced this sometimes? Haven’t you ever felt this when listening to music, or looking at a landscape in the infinite tenderness of twilight? That evening, sitting on the bridge, my eyes lost on the horizon and the clouds, it seemed to me that from a tower I was watching my entire life, past and future, and I don’t know why I had a dreadful presentiment of sadness.

The ship sailed slowly toward some lights that, beneath the tenuous film of clouds, were confused in the distance with the stars barely shining in the sky. Little by little the lights began to multiply and grow, as if Venus that night had wished to generously lavish herself over the sea. Then, imprecisely, hazy in the half-light and the distant fog, the dark blocks of the mountains began to separate from the sky. The happy, brilliant lights twinkled above, below, scattered across that deep sky of mountains that looked more and more familiar, more hospitable, with arms open to the ship, until suddenly, on the left side, like a fantastic illumination of fireworks, the whole sea lit up at the foot of the mountain. The passengers, leaning against the rail on deck, just under my observation point, with the joy that inspires sailors as they near a hospitable port, began to stir with an immense happiness full of voices and laughter. The lights of Macuto created that illumination, Cristina. It is our elegant beach, our fashionable watering place, the Venezuelan equivalent of Deauville or San Sebastian.

The ship, all lighted up, too, just like a lover pacing the street where his beloved lives, moved sideways, drawing closer and closer to the lights. They, with the gaiety of a celebration, sparkled and were like a thousand friendly voices that were shouting at us from the land.

The Venezuelans then, full of enthusiasm, started to surmise, “Surely from there they can see us too!”

I sank into the darkness on the bridge, silent, alone, observant, squeezed into the angle formed by two lifeboats. From my high position, watching the spectacle, I thought about a morning that I could only vaguely remember when I was very little, with curls down my back and wearing little white socks. With Papa I had boarded the ship that took us to Europe. At sight of the ocean, I had suddenly felt terror of the unknown, and when I embarked, I had grabbed my nurse’s hand in fright. She was an indolent, dreamy mulatta who always took care of me with maternal affection from the day I was born, and she even took care of you sometimes, too. She died in Paris, you remember. A victim of the harsh winter.

With my eyes fixed on the multiplying lights of Macuto, I tried hard to recall Uncle Pancho’s long, thin face. He was Papa’s older brother, who had gone to the boat to say goodbye to us. I remembered how before it sailed he caught me in his arms and he took me all over the ship; he had told me that the furnace was a hell where the stokers, really demons, threw disobedient children who climbed on the deck railings. I remember how then he had kissed me many times, and how at last, without another word, he put me down, gave me a package of candy and a cardboard box where a golden-haired doll dressed in blue was sleeping! It had been twelve years since all that. Oh! Twelve years! Of the three travelers who departed that morning, I alone was returning. Would Uncle Pancho be there tomorrow to meet me? Maybe not. However, I had cabled my arrival, and someone surely would be waiting for me. But who? Who would it be?

Macuto was hidden again, just as it had appeared, behind a sharp bend in the coastline and soon the ship began to slow in front of the bay that forms the La Guaira port. Before dropping anchor, the boat bobbed back and forth a few minutes, stopped lazily, sheltered by the immense mountains studded with constellations of light; in the warm atmosphere it seemed to rest at last from its incessant running.

As I was saying, Cristina, there is always a sad mystery about arrivals. When a boat stops after having run for a long time, it seems that all our dreams stop too, and all our ideals fall silent. Smoothly sliding along on a vehicle is very conducive to spiritual enrichment. Why? Maybe it’s because your soul, as it feels you racing without moving your feet, dreams it’s flying far from the earth, completely detached from all matter. I don’t know; but I remember that night well. The ship was standing still before La Guaira and I fell asleep imprisoned and sad as if they had cut down a harvest of wings in my soul.

I woke up next morning when the boat began moving in to dock. The joy of the morning seemed to pour in with a ray of sunshine that broke against the porthole window and flooded my cabin with scintillating light. As soon as I opened my eyes I looked about an instant, and as if the dazzling light and sunny brightness of the morning had evaporated all of last night’s melancholy, feeling happy and curious to see new places, I ran to peek through the porthole. As the boat sailed slowly, a panorama slipped gently past. I had often heard people ponder the ugliness of the town of La Guaira. Given this preconception, the view surprised me agreeably that morning, like a smiling face we thought unknown that turns out to be the face of a childhood friend. Before my eyes, Cristina, right on the ocean’s edge, a great yellow, barren mountain rose abruptly. It was flowered with little houses of every color, which seemed to clamber up and form stepping stones along the sloping bank and cliffs with the daring of a flock of goats. Vegetation sprang up at times, whimsically, among the tiny houses that hung so rashly at the edge of ravines and that had the ingeniousness and the unreal quality of those little cardboard houses that the Mothers at the college used to strew about the nativity scene at Christmas. The sight of them aroused in my heart the innocent rejoicing of the villancicos that every year announced the song-filled excitement of Christmas vacation. I thought with great pleasure that now I was going to abandon the monotony on board ship for the cool shade of trees and for the freedom to walk about on solid ground. I suddenly felt the immense and happy curiosity of someone awaiting great surprises, and while outside, amid the squealing of cranes and pulleys, the noisy work of disembarking began, I, in my cabin, avid to be on deck, began to dress feverishly.

I remember that I had just put my things together and was picking up my hat, when I heard Mrs. Ramirez’s voice, speaking with her indolent and musical criolla inflections, “This way, this way! She must be dressed by now! Maria Eugenia! Maria Eugenia! Your uncle!”

When I heard these magic words I flung myself hurriedly out of the cabin, and in the narrow passageway I could see, with his back to the light, the tall and slightly stooped figure of a gentleman dressed in white linen who was advancing toward me. I was shaken again by last night’s intense emotion; I thought about Papa; I felt my early childhood reborn suddenly; and emotional, weeping, I ran toward the approaching man, holding out my arms and calling to him with a cry of joy:

“Oh! Uncle Pancho! Uncle Panchito!”

He hugged me affectionately against his white shirt bosom while he answered in a slow, nasal voice, “I’m not Pancho. I’m Eduardo, your uncle Eduardo, don’t you remember me?”

And taking me gently by the arm he led me out of the passageway toward the clear light on deck.

My first emotion had dissipated instantly when I realized that disagreeable quid pro quo. The impression produced by my uncle’s figure in the clear light of day completed my disenchantment. That impression, Cristina, speaking quite frankly, was the most disastrous that anybody has ever produced in the eyes of another.

In the first place I must tell you that the features of my uncle and guardian Eduardo Aguirre were absolutely unknown to me. In my infancy this brother of Mama used to live with his family in a place somewhat distant from Caracas, and if I ever saw him, he made no impression on me, since I never catalogued his features in that distant collection of faces that I had always preserved in my mind, though confused and unclear, rather like portraits that have been exposed too long to bright sunshine.

Nonetheless, without knowing Uncle Eduardo by sight, I knew him very well by reference; certainly, Papa named him frequently. Every month letters arrived from Uncle Eduardo. I can still see Papa when he used to receive them. Before opening them, he would turn the envelope over and over in his slender hands, with an elegant and disapproving gesture. Those letters must have always worried him, because after reading them he would say nothing for a long time, and he was dejected and pensive. Sometimes before he could make up his mind to slit the envelope, he would look at me, and as if he wanted to relieve himself with a semiconfidence, he would softly muse, “From that imbecile Eduardo!”

Other times, he would throw the unopened letter on a table as one throws down cards after losing a game, and then, probably to vary his vocabulary — expressing the same idea nevertheless — he would ask himself this question: “What will that fool Eduardo tell me today?”

I had always attributed the depression that the letters produced in Papa to money troubles. And I attributed the names he called Uncle Eduardo, who administered his estates, to the same cause. However, the morning of my arrival, I had no sooner gone on deck, where in full light I could cast a critical eye on my uncle’s person, than I immediately acquired the certainty that Papa was profoundly right when he pronounced those brief and decisive judgments every month.

But since it seems to me of interest for the future to describe Uncle Eduardo in detail, that is to say, this Uncle Eduardo of my first impression, I’m going to sketch him briefly just as I saw him that morning on board the Arnus.

Picture that at the short distance with which one usually chats on board ship, next to a patch of sunlight and a coil of rope, he was facing me, leaning against a rail, thin, jaundiced, stooped, very pale, with a limp mustache and with the look of someone ill and sad. I later learned that during his youth malaria had undermined his health and that now he suffers from some liver disease or other. His white linen suit hung on his skinny, ungainly body as if it had not been made for him, which gave him a very definite look of carelessness and neglect. He was talking, and as he talked he kept gesturing toward himself, in a horribly awkward way that had no rhythm nor relation whatever to what his voice was saying. His voice, Cristina, besides being nasal, was singsong, monotonous, and very peevish. I looked at him, wondering, and while I was mentally shouting, “Oh! How ugly!” I attempted, behind a friendly smile, to hide my critical appraisal, so little flattering to the one producing this bad impression. And with the objective of dissimulating even better, I began to inform myself about the whole family. I asked him about Grandmother, Aunt Clara, his wife, and his children. But it was useless. My affable interrogation was purely mechanical. My thoughts followed my eyes, and my insatiable eyes never tired of scrutinizing him from top to toe, while in my ears, full of truth and life now, I seemed to hear echoing anew Papas words: “That imbecile Eduardo,” “That fool Eduardo.”

Conversing gracelessly and lifelessly, his back leaning against the rail, and with the coil of rope at his feet, he told me that everyone in the family wanted very much to see me; that with the sole objective of meeting me he had come from Caracas yesterday morning because they had announced the ships arrival for that afternoon; that for that reason, he had spent last night in Macuto; that he had seen the ship go by around seven o’clock; that at any minute his wife and four children should show up on the dock for they had left Caracas by auto more than an hour ago; that probably Uncle Pancho Alonso would come, too, on his own because he’d heard him say something to that effect; that having certain urgent business to dispatch in La Guaira, it seemed best to him for us all to have lunch together in Macuto; that as I would see, Macuto was cool, bright, and very pretty; and that, finally, as soon as we ate we would drive up to Caracas where Grandmother and Aunt Clara were waiting for me consumed with impatience.

And while he was saying this I was looking at him with that amiable smile, judging him ugly, awkward, and poorly dressed. However, in spite of the great lying smile, my countenance must have reflected something because suddenly he said, “I came to meet you like this, you see, because here you can’t wear anything but white, it’s so hot! And right now I warn you that La Guaira will make a bad impression on you. It’s horrible: extremely narrow streets, poorly paved, blistering sun, very hot, and,” he added, lowering his voice mysteriously, “many blacks! Oh! It’s horrible.”

I answered with the amiable smile petrified on my lips, “It doesn’t matter, Uncle, it doesn’t matter. Since we’ll only be passing through, it’s not important!”