Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

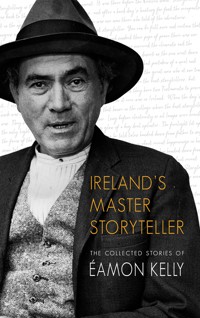

In this collection, actor and seanchaí (traditional storyteller) Éamon Kelly's finest stories are collected for the first time: stories of the real Kerry and the magical past of the Gobán Saor, the heartbreak of emigration, the stations, the priests, the courting and dancing, the war between the sexes. Kelly mines a rich seam of humour and sadness out of resilience of a people rich in hospitality and generosity, imagination, culture and tradition.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 543

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1998

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Éamon Kelly, 1998

978 1 78117 841 6

978-1-78117-842-3Ebook only

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Introduction

Storytelling is the oldest form of entertainment. It was there before the written word. Storytelling goes back to the time when people lived in caves, and after a hard day’s hunting for food the occupants sat in the open air and when supper was over there was one man there who told of the adventures, dangers and escapades of the day. He was the first storyteller.

You can be full sure and certain that when the Red Indians sat around the camp fire at night and smoked their pipe of peace there was one brave who told of the glories of his nation; tales of how his ancestors survived the elements and the hostilities of a neighbouring tribe.

When the Arab train camped in the desert as the sun went down and the camels were arranged in a circle, the fires were lit. When they had partaken of a meal and rested, there was one man there who told the history of his people and of the great men who at one time walked the world. I have heard it said that the Arabs and the Irish are the best storytellers, but where do you leave the Jews? They were good storytellers too and they have two Testaments to prove it.

I always associate storytelling with the fireside, and so it ever was in Ireland. When the day’s work was over in the fields the people crowded into that house in the village where the best storyteller was. They sat on chairs, stools and even on the floor. Long before electricity or oil lamps were heard of the only light was from the fire or the spluttering glow of a bog deal splinter. The firelight lit up the faces of the listeners and that of the storyteller as he told tales handed down from father to son – some tales that went back to Oisín and the Giolla Deachair and some about recent happenings in his own district.

As well as being a good narrator, the storyteller was the local historian and genealogist – a walking library, the repository of folk wisdom and custom. In the days before radio and television the people provided their own entertainment in the long winter nights. After the story was told there was a song or maybe a dance. Many of the kitchen floors in the old days were made of mud but there was always a large stone flag in front of the fire. The stepdancer danced on this and with his iron-tipped shoes knocked sparks out of it. I often heard tell of the front door being taken off its hinges and placed in the middle of the mud floor for two people to dance the challenge hornpipe.

If there were no musical instruments the young people lilted the dance tune and men lit bog deal splinters in the fire and circled the dancers with a ring of light. Mummers were not unknown in country districts then, and in my own place on St Bridget’s Eve, boys and girls would dress up in the most outlandish clothes and pull a piece of old lace curtain over their faces as a mask. They used to carve a face on a large turnip with the eyes and mouth deeply incised. They would scoop out the centre of the turnip and put a lighting candle into it.

The sculpted head was fixed to the handle of a broom and a stick put across to hold a coat. With a headscarf this effigy was carried in procession from house to house and the light coming through the eyes and mouth of the head looked eerie in the dark. When the mummers came to the storyteller’s house the floor was cleared and they danced a set and sang a song. The effigy was held high and money was collected. Then they all settled down and listened to the storyteller tell of the man who was apprenticed to a doctor or the tale of Dean Swift and his serving man.

In a gathering like this you had all the rude elements of the theatre. The storyteller provided the comedy and sometimes the tragedy because he could bring a tear when he spoke of the death of Naoise and the Sons of Uisneach. The song was there, the music, the dance and the dressing up. I call this form of entertainment ‘theatre of the hearthstone’ – a diversion having its seed in the time when our forefathers sat at the mouth of a cave and listened to the happenings of a day’s hunting.

Éamon Kelly

Beyond the Horizon

My father never took off his hat except when he was going to bed and into Mass, and my mother said he slept in the two places. At that time every man covered his head. There was respect for the brain then.

As well as covering the head the hat is a handy receptacle. If you are caught short you can give a feed of oats to a horse out of a hat. You can gather apples in the orchard or bring in new laid eggs from the hayshed. In fact, you could nearly put a hen hatching in a hat … well, a bantam or a guinea hen.

Headgear gives a man authority. The popes and kings and bishops know this. They always cover their heads when they have something important to say. And where would the storyteller be without his hat when he sits at the fireside to tell a story?

In the long winter nights long ago, the talk’d often turn to some great man who was in the world one time. In our house we’d often talk of Aristotle. Of course the old people had a more homely name for him. They used to call him Harry Stottle. He was a great schoolmaster, and the way he used to teach was walking around the fields so the pupils could be thinning turnips or making hay while they were learning their lessons. In those days great store was set by the pupil’s knowing the name and the nature of everything that flew and everything that ran, of everything that grew, and everything that swam. But the old people held that despite all his great knowledge, there were three things Harry Stottle could not understand. And these were the ebb and flow of the tide, the work of the honey bee, and the fleetness of a woman’s mind, which exceeds the speed of light!

There were these two Kerrywomen. They met on the road one day. One was going to town and the other was coming from town – this now was away back in 1922 when the IRAye were fighting the IRAh. And all the bridges were blown down. So after a heavy day’s rain you’d wet more than your toes fording the river!

The woman going to town, who was on the small side, said to the woman coming from town: ‘Were you in town what time is it what price are eggs is the flood high?’

As quick as lightning the woman coming from the town said: ‘I was three o’clock one and fourpence up to my arse girl!’

Agus ag trácht dúinn ar uisce, as the man said when he got the half of whiskey at the wake, the Ceannaí Fionn used to sail the watery seas between Iveragh and the continent of Europe long before the Danes discovered Ireland. He used to take over what’d keep you warm on the outside and bring back what’d keep you warm on the inside. He used to trade wool for wine. Not a bad swap!

The Ceannaí Fionn’s right hand man was Cluasach Ó Fáilbhe, and like Harry Stottle, for they were long headed men, they wondered greatly where the tide went to when it was out and where it came from when it was in. And often on their journeys to and from France and Spain they looked out over the Atlantic Ocean and they wondered too what was behind the horizon, for at that time no one knew. So they went to find out but the horizon always remained the same distance in front of them. After many months they came back nearly demented from hunger and thirst, although ’tis said all great explorers at that time took enough provisions to last them for seven years going, seven years coming and seven years going astray. They came back and this was the story they told.

One day they saw a great hole in the middle of the ocean and the sea on all sides pouring down into it.

‘Ah ha,’ says the Ceannaí Fionn, ‘we know now! That’s where the tide goes to when it is out. But where in the devil does it come from when it’s in?’ He hadn’t the words out of his mouth when an almighty pillar of water shot up out of the hole bringing with it broken ships and every kind, class, form and description of wreckage.

‘That,’ said the Ceannaí Fionn, ‘is where the tide comes from when it’s in!’ A wall of water as high as Mangerton mountain drove the ship westward before it till finally they came to a wall of brass. The sailors hit the wall with their oars and so loud was the report that all the fish stuck their heads up out of the sea. I suppose they thought it was dinner-time!

They sailed along the wall till they came to a breach high up in it. Now as sailors are knacky with ropes, they made a rope ladder, threw it up and the Ceannaí Fionn sent up a sailor to see what was at the other side of the horizon. When the sailor got to the top of the wall he gave a great crow of delight and jumped down the other side. Now they had only three sailors on board the ship, so the third fellow got a tight warning, to come back and tell what was at the other side. Mo léir! When the third sailor got to the top of the wall he nearly hopped out of his skin with delight and turning his head he said, ‘Críost go deo! Did I ever think I’d live to see it!’

And giving vent to one father and mother of a great yehoo he jumped down the other side.

Now if the Ceannaí Fionn and Clusach Ó Fáilbhe were ever again to see Iveragh they knew they’d have to pull down the rope. This they did. And what was behind the wall? Nothing would convince the people who heard the tale but what the sailors saw was women. The Ceannaí Fionn said no. That they had plenty of time to reflect on it and his belief was that what the sailors saw was the face of God. His belief was that the world was not made all in one slap, all in one week like we were told. Even the eastern half of it would be too big a job for that.

His belief was that the brass wall was a sort of hoarding the Almighty put up to keep out the sea while he was finishing the western half of the world! And very likely!

If they didn’t see what was at the other side of the horizon, Cluasach Ó Fáilbhe got a glimpse of another world and this is how it happened. On their way home they were often hungry and they used to throw out the anchor and do a bit of fishing. One day when they went to pull in the anchor they couldn’t, so Cluasach Ó Fáilbhe said he’d go down to see what was holding it. He took a deep breath and down with him along the chain to find that the anchor was hooked under the lintel of a door. He went into the house and there inside was, oh! a beautiful young girl.

‘Oh, Cluasach,’ she said, ‘I’m watching you every day passing above in the ship. I’m out of my mind in love with you and will you marry me?’

‘All right,’ said Cluasach, ‘I will. But I’d like to go home first and talk to my mother.’

‘If you go home,’ she said, ‘you’ll have to give me your solemn promise that you’ll come back again, and if you break that promise,’ she said, ‘and if you are ever again on the sea, I’ll go up and bring you down myself, for I can’t live without you!’ She had it bad!

Cluasach gave her his promise and he disentangled the anchor from under the lintel of the door and up the anchor flew bringing him with it. He told the Ceannaí Fionn about the beautiful woman in the house below.

‘Don’t mind her,’ says the Ceannaí Fionn, ‘You’d get your death from rheumatics living down in that damp old place.’

He came home and he told his mother, and the mother wouldn’t hear of it either. Marrying foreigners! What did he think! She kept him off the sea, from that out – it was no more ships for Cluasach. Time wore on and he couldn’t get the image of this beautiful woman out of his mind. One day the men were playing football below in the strand. One awkward fellow kicked the ball into the tide, and Cluasach, forgetting himself, went in after it. And there she was inside in the waves waiting. She threw her two hands around him and brought him away down with her, down under the sea, down to Tír Fó Thoinn. And he never came back, and I suppose he married her, but he used to send a token. Every May eve for fifty years after, the three burnt sparks used to come into Trá Fraisc. Didn’t he live a long time down there with her! Marriage never shortened a man’s life if he meets the right woman.

Going to America

We lived in an inland parish and the men sitting around my father’s fire talking about the Ceannaí Fionn, well, you could count on the fingers of one hand the number of those that ever saw the salt water, except the man going to America. And as the old woman said, ‘God help us he saw enough of it!’ And I remember a fierce argument cropped up between Batty O’Brien and Coneen Casey, a thin wiry fellow, as to how long it was since the first Irishman set foot in America. Weren’t they caught short for a topic of conversation!

‘Well now,’ says O’Brien, a man of large proportions and an historian to boot, ‘I can answer that question. The first Irishman to set foot in America was St Brendan the Navigator, for of course ’twas he discovered America. Although he kept his mouth shut about it.’

‘How long ago would that be so,’ says Casey, ‘since St Brendan set foot in America?’

‘I can tell you that,’ says O’Brien, ‘St Brendan was born in Fenit, in Kerry around the year ad 500, and he died in Anachuin – I have all this now from the lips of a visiting ecclesiastic – he died in Anachuin about 580. We’ll take it now that he did his navigating in his prime, say from 525 to 540. Add all that up and take it from the year we are living in and it will bring you to within a hen’s kick of fourteen hundred years since St Brendan set foot in America.’

‘Is that all you know?’ says Casey, sort of cool. ‘Irish people were going to America before that.’

‘Can you prove it?’ says O’Brien.

‘Faith then, I can prove it,’ says Casey. ‘Otherwise I wouldn’t have drawn it down. My own grand-uncle, Thade Flor, was going to America after the famine. In a sailing vessel they were. They were becalmed one evening late, about two hundred miles out from the coast of the County Clare. So they threw out the anchor and went to bed for the night – what did they want up for? In the morning there was a stiff breeze blowing. They pulled in the anchor, and do you know what was caught in the hook of it? The wheel of a horse car!’

‘And what does that prove?’ says O’Brien.

‘It proves,’ says Casey, ‘that Irish people were going to America by road before the flood!’

I myself saw the tail-end of that great emigration that half-emptied the countryside. Often as a small child going to school I called into a neighbour’s house to say goodbye to a son or a daughter that was going to America that morning. One kitchen I went into was so dark inside the poor man couldn’t shave himself there. There was only a tiny window. If you threw your hat into it, it would be like an eclipse of the sun.

And I have a clear picture in my mind of Pats Pad Duinnín, barefoot in his thick woollen undershirt and long woollen drawers covering him from his Adam’s apple down to his ankles – I’d say he got out of that regalia very quick when he hit New York at ninety in the shade. And there he was outside the open door, where he had plenty of light, shaving himself in a looking glass held up by his small brother. So it was, ‘Up a bit, up a bit, up a bit. Will you hold it! Down a bit. Where am I now? Tilt it, but don’t crookeden it!’

And you know, make it your own case, it was very hard for small Jer D. to judge where his face’d be.

‘Hether a bit, over, down! God in heaven I see the clouds but I don’t see myself. Up a bit, down a bit. Blast it! Will you hold it straight. I’ll look sweet going into the train with a skelp gone outa the jaw!’

He was lathering himself with Ryan’s Keltic soap, and after saying goodbye to him I remember wiping the soap off my hand on the backside of my pants as I went down the road to school. I remember too being taken by a neighbour’s daughter to a dance – I was only ten at the time – given in a house in the locality for those going to America. Good fun it was too – the best American wakes they say were in Ireland – and the best Irish wakes in America!

The old people sat around the hearth, drooped and go brónach, the red glow of the fire on their faces, their feet keeping time to the music. A set dance was in full swing, the young dancers knocking fág an bealach out of the flagged floor, the lamplight throwing their dancing shadows on the whitewashed walls. Down at the butt of the kitchen the musicians were playing. And it was said that these musicians never repeated a tune in the whole run of the night. They had a name for every tune. ‘The pigeon on the gate’, ‘The turkey in the stubbles’, ‘The cat rambled to the child’s saucepan’, ‘The maid behind the bar’, ‘Tell her I will’!

If a strange musician didn’t know the local names, and the dancers wanted a specific tune, there were rhymes to recall the tune to the fiddler’s memory, like, ‘When Hannie got up’!

Oh when Hannie got up to admire the cups

She got a stumble and a fall,

Fell on the chair and broke the ware

At Thadeneen Andy’s ball!

Or another one was:

Take her away down the quay

I won’t marry her at all today

She’s too tall I’m too small

I won’t marry her at all at all.

In some places those dances were outlawed. They used be raided. In fact a well-known Kerry footballer, the first time he saw a flashlamp – carbine they used to have before that, the stink of it! – he told me that he was sitting behind the door on a half-sack of bran, a girl on his knee, when the curate flashed a light into his face. And coming at him as it did, all of a sudden out of the dark – especially when he had something else on his mind, he thought it was the end of the world. The effect it had on that man. Put his heart sideways. He never scored after!

All dancing was banned, even in the daylight! Didn’t I myself hear Father Walsh saying off the altar: ‘I’ll put an end to the ball nights. I’ll put an end to the porter balls and the Biddy Balls! While there are wheels under my trap I’ll go into every corner of the parish … I don’t care how far in from the public road these … balls are held to evade ecclesiastical detection. I’ll bring ’em down out of the haysheds! It has come to my ears that young women of marriageable age in this parish have remarked “How can we get men if we don’t go to the balls?” I’ll tell ’em how they can get men. I’ll tell ’em how! They have only to come round to the sacristy to me any Sunday after Mass and I’ll get plenty of men for ’em without any balls!’

Sentries used have to be posted outside the dance house to raise the alarm when they heard the wheels of Father Walsh’s trap – that was before he got the rubber tyres!

One night is gone down in history. Around twelve when the hilarity was at its peak, high jinks in the kitchen and capers in the room, the front door burst open and a sentry rushed in shouting, ‘Tanam an diúcs! He’s down on top of us. He’s coming in the bóthairín!’ Well the back door wasn’t wide enough to take the traffic. That for terror! The women’s coats and shawls were thrown on the bed below in the room, and in the fuss and fooster to get these, two big women got stuck in the room door. Couldn’t go’p or down! Until one clever man put his hand on one of their heads, pushed her down till their girths de-coincided and they were free.

Moll Sweeney was the last one out of the house, pulling her shawl around her. Of course when she left the light she was as blind as a bat and who did she run straight into – head-on collision – but the parish priest, who was coming in the back way – look at that for strategy to catch ’em all. And Father Walsh to keep himself from falling in the dirty yard, and ruining his new top coat that he had bought that day in Hilliard’s Chape Sale, had to put his two hands around Moll to maintain any relationship with the perpendicular. Moll was trying her level best to disentangle herself.

‘Will you leave go of me! Will you stop I said! Stop I’m telling you. Take your two hands off me whoever you are, and isn’t it hard up you are for your hoult and the priest coming in the front door!’

The Gobán Saor

But to come back to the American wake. Between the dances there’d be a song. It would be hard enough to get some of those fellows to sing. One man might be so shy he’d want two or three more standing in front of him, ‘Shade me lads!’ Or he might run down below the dresser or over to the back door where the coats’d be hanging and before he’d sing he’d draw a coat in front of his face.

As the night wore on there would be many young faces, as the man said, with hunger paling, around the kitchen. That way down in the room refreshments were being served. When it came to my turn to go down, there I saw and heard my first storyteller. A great liar! A stonemason by trade. There he was with his back to the chimney piece shovelling in currant bread and drinking tea out of borrowed delph. When he was finished he blew the crumbs off his moustache, and fixing his eye on a crack over the room door he began, ‘A trade,’ says he, ‘is as good as an estate. A man that knows his trade well can hold his head high in any community, and such a man was the Gobán Saor. He was in the same line of business as myself, he was a stonemason. No word of a lie he had the gift and this is how he got it.’

‘It so happened one day that the Gobán Saor was out walking when who should he see approaching but an old man with a bag on his back and he bent down to the ground with the weight of it.

‘“A very good day to you,” says the old man, “are you going far?”

‘“To the high field to turn home the cow,” says the Gobán. “Do you know me?” For the old man was driving the two eyes in through him.

‘“I don’t,” says the old man, “but I knew your father well.” With that he left down the bag and sat on top of it.

‘“It was ever said,” says the old man, “that your father would have a son whose name would be the Gobán Saor and this son would build the round towers in Ireland – monuments that would stand the test of time, and the people in future generations would go out of their minds trying to find out why they were built in the first place. One day the Gobán Saor would meet an old man who would be carrying on his back the makings of his famous monuments. Did your father ever tell you that?”

‘“He did not,” says the Gobán, “for he is dead with long.”

‘“I think I’ll be soon joining him,” says the old man, “but I have one job to do before I go. Where would you like to build your first round tower?”

‘“I’m going to the high field to turn home the cow,” says the Gobán, “so I might as well build it there.”

‘They went to the high field and the stranger drew a circle with his heel around where the cow was grazing. He opened the bag and they dug out the foundations. Then he gave the Gobán Saor his traps; trowel, hammer, plumb-rule and bob, and he showed him how to place a stone upon a stone. Where to look for the face of the stone and where to look for the bed, where to break the joint, and where to put in a thorough bond.

‘The wall wasn’t long rising, and as the wall rose the ground inside the wall rose with ’em, and they were a good bit up before they thought of the door, and they put in a thin window when they felt like it. When they got thirsty they milked the cow and killed the thirst. The tower tapered in as they went up and when they thought they were high enough the Gobán came out of the top window to put the coping on the tower. By this time the field was black with people all marvelling at the wonder. The Gobán’s mother was there and she called out, “Who’s the young lad on top of the steeple?”

‘“That’s your own son,” they told her.

‘“Come down!” says she, “and turn home the cow!”

‘On hearing his mother the Gobán Saor climbed in the window. The ground inside the tower lowered down with him. When he was passing the door high up in the wall the Gobán jumped, and the cow jumped, and the old man jumped and that was just the jump that killed him and he is buried where he fell, the first man in Ireland with a round tower as his headstone – Daniel O’Connell was the second!

‘The Gobán picked up his bag of tricks, and after he turned home the cow, his mother washed his shirt and baked a cake, and he went off raising round towers up and down the country. He married and we are told he had a big family – all daughters, bad news for a tradesman, except for an only son. The son, as often happens, turned out to be nowhere as clever as his father, so the Gobán said he’d have to get a clever wife for him and this is how he set about it.

‘One day he sent the son out to sell a sheepskin, telling him not to come back without the skin and the price of it – craiceann is a luach. Everyone laughed at the son when he asked for the pelt and the price of it, except one young woman. She sheared the wool of the pelt, weighed it, paid him for the wool and gave him back the pelt and the price of it.

‘The Gobán said to the son: “Go now and bring her here to me.” The son did and the Gobán put her to another test to make sure. He sent her out with a thirsty old jennet he had, telling her not to let him drink any water unless it was running up hill. She took the jennet to the nearest stream and let him drink his fill. And it ran up hill – up his neck. She married the son and was the makings of him!

‘When the Gobán Saor had finished the round towers in Ireland, he turned his hand to building palaces, and as every palace he built was always finer than the one before, his fame spread until the King of England sent for him to put up a palace for him, for he wasn’t satisfied with the one he had.

‘This morning the Gobán Saor and his son set out for England and when they were gone awhile the Gobán Saor said to his son, “Shorten the road for me.”

‘And the son couldn’t so they turned home. The following morning they set out for England and when they were gone awhile the Gobán Saor said to his son, “Shorten the road for me.”

‘The son couldn’t so they wheeled around for home a second time. That night the son’s wife said to her husband, “I gcúntas Dé a ghrá ghil, what’s bringing ye home every morning. Sure, at this gait of going ye’ll never make England.”

‘“Such a thing,” says he, “every morning when we’re gone awhile my father is asking me to shorten the road for him and I can’t.”

‘“Well where were you got,” says she, “or what class of a man did I marry! All your father wants is for you to tell him a story and to humour him into it with a skein of a song.”

‘Oh a fierce capable little woman! Pé in Éireann é, the third morning the Gobán Saor and his son set out for England and when they were gone awhile the Gobán Saor said to his son: “Shorten the road for me.”

‘And the son settled into:

Doh idle dee nah dee am,

Nah dee idle dee aye dee am,

Doh idle dee nah dee am,

Nah dee ah dee aye doh!

‘And with that they set off in earnest. The son humoured the father into the story of the Gadaí Dubh, and they never felt the time going until they landed over in England where the King and Queen were down to the gate to meet ’em.

‘“How do I know you’re the right man,” says the King.

‘“Test me,” says the Gobán.

‘So the King pointed out a flat stone up near the top of the old palace, and told the Gobán to cut out a cat with a tail on him on the face of that stone. The Gobán took his magic hammer and aimed it at the stone and up it flew and of its own accord it cut out a handsome cat and it isn’t one tail he had but two – the Gobán’s trade-mark, a thing that was widely known throughout Europe at the time.

‘“Fine out,” says the King. “You’re elected”, taking the Gobán to one side and showing him the cnocán where he wanted the new palace built.

‘“And I’ve the stones drawn and the mortar mixed,” says the King.

‘So the Gobán Saor and his son fell to work and cut the foundations, and it wasn’t long at all till the palace was soaring for high, with a hall door fifteen feet off the ground and a ladder going up to it that the King could pull in after him in case of any scrimmage, for there is no knowing how trí na céile things were in England at that time.

‘Well, when the King saw the way the palace was shaping, he was rubbing his hands with delight, and he was every day saying to the Gobán, was it true that the last palace he built was always finer than anything he ever built before? The Gobán said that was correct.

‘“I’m glad to hear it,” says the King, “and as sure as you’re a foot high the day the palace is finished, there’s a surprise in store for you.”

‘The Gobán was wondering what these words meant and this is how he found out. ’Twas a daughter of Donaleen Dan’s that was housekeeping for that King of England at the time his own wife was that way and not able for the work, and every day when the Gobán and his son’d come in to their dinner the two of ’em and Miss Donaleen’d be talking: Bhí an Ghaeilge go blasta aice siúd, agus is i nGaelige a bheidís ag caint i gcónaí, and the King of England didn’t know no more than a crow what was going on!

‘“Bad tidings,” says Miss Donaleen this day. “That King is stinking with pride, and he’s saying now that if the Gobán Saor and his son go off and build another palace for the King of Wales or the King of Belgium, it will be better than his own, and then he won’t have the finest palace in the world. So as soon as ever the job is finished he’s planning to cut the heads down off the two of ye! That’s the surprise you’re going to get!”

‘Wasn’t it far back the roguery was breaking out in ’em, eroo!

‘The Gobán slept on this piece of information and in the morning he said to his son: “If my plan don’t work I can see the two of us pushing nóiníns before the hay is tied.”

‘“Cuir uait an caint,” says the son. “Here’s the King coming.”

‘Along came the King rubbing his hands with delight and he said to the Gobán, “Is this now the finest palace in the three Kingdoms.”

‘“It is,” says the Gobán.

‘“And tell me,” says the King, “is it long until you’ll have it finished?”

‘“Only to put the coping on the turret,” says the Gobán, “but the implement I want for doing that is called the cor in aghaidh an chaim…”

‘“English that for me,” says the King.

‘“’Tis the twist against crookedness,” says the Gobán, “but bad manners to it for a story, didn’t I forget it at home in Ireland after me, so I’ll hare back for it and bring my son to shorten the road for me.”

‘“You’ll do no such thing,” says the King, “you’ll stand your ground and I’ll send my own son for it.”

‘Well, that was that for as we all know there’s no profit in going arguing with a King.

‘Now at home in Ireland the Gobán’s son’s wife, that fierce capable little woman, was baking a cake this day when who walked in the door to her but the King of England’s son.

‘“Such a thing,” says he, “I’m from over.”

‘“Is that so,” says she. “Is it long from the palace?”

‘“’Tis nearly ready now,” he said, “only to put the coping on the turret, but they forgot the implement for doing that, ’tis called ‘the twist against crookedness’.”

‘She tumbled to that: “You’ll find it there in the bottom of the bin,” she said, “and if you’re not too high and mighty in yourself you can stand up on the chair and stoop down for it.”

‘And if he did, she kicked the chair from under him, knocked him into the bin, banged down the cover and locked it.

‘“Ah-ha-dee,” says she. “You’ll remain a captive in there until my husband and my husband’s father’ll come home to me, so write out a note to that effect and hand it out through the mousehole!”

‘He did, and she gave the note to the Gobán’s pet pigeon, and he knew where to go with it – why wouldn’t he! And the plan worked and she hadn’t long to wait and she knew who was to her coming up the bóthairín when she heard:

Doh iddle dee nah dee am.

Nah dee iddle dee aye dee am,

Doh iddle dee nah dee am

Nah dee ah dee aye do.’

That stonemason had never been a mile from a spring well, but to hear him talking you’d swear he’s been to the moon and back. Going away was the topic on the tip of everyone’s tongue that night and the storyteller liked it to be known that he was away himself. This is how he acquainted us of it.

‘In my father’s time things were slack at the stonemasoning and my mother said to me: “Isn’t it a fright,” says she, “to see a big fosthook like you going around with one hand as long as the next, and why don’t you go away and join the DMP’s for yourself!”’

‘They were the old Dublin police, a fine body of men. So I took her at her word and hit for Dublin and the depot, and joined up, and after a tamall of hard careering around the barrack square, a solid grounding in acts of parliament and all that I was put into a new uniform and let loose in the city of Dublin!’

‘My first assignment was public house duty in Parnell Square – kind of a swanky place. I tell you I wasn’t long there when I instilled a bit of law and order in them lads with regard to late closing and that. Things rested so. I was this night going along … it would be well after half eleven I’d say – when I saw a light coming through the hole in a shutter of a certain establishment. I went up and put my eye to the hole and what was it, you devil, but a line of lads up to the counter with loaded pints! I banged on the knocker and the publican came out. “What’s this?” says I. “What class of carry on is this?”

‘“Oh Ned,” says he, “sure you won’t be hard on me.”

‘“Ned!” says I. “What Ned! I don’t know you my dear man, or the sky over you!”

‘“I’m a cousin of your own twice removed, I’m a boy of the Connor’s from the cove of Sneem!”

‘“Jer Dan’s son,” says I.

‘“The very man,” says he.

‘“Well now,” says I, “you could have knocked the cover off my pipe, I never knew you were in Dublin or in the public house trade.”

‘“Oh I am,” says he, “come on away in till we try and soften things out.”

‘Well, seeing that he was a connection and all to that I went in with him, but I must say this much for him. He was not a grasping fellow. I was no sooner in than he cleared the premises, sat me down and landed me out a healthy taoscán from the top bottle in the house and told me I’d be welcome at any time which I was!

‘I was this night above inside in the cousins with my shoes off toasting my toes to the fire, a smart smathán of punch in front of me. We were tracing relationships when around half past twelve the thought was foreshadowed to me that the DI might be around on a round of inspection, do you see. I stuck the legs into the shoes, mooched out to the front door and there he was coming up along, so I pulled the door after me and pretended to be standing in from the rain. Up he came.

‘“Night Ned,” says he.

‘“Night Officer,” says I.

‘“Be telling,” says he.

‘“Nothing to tell,” says I, “the publicans in this quarter are living up to the letter of the law.”

‘“Good,” says he, “I’m hearing great accounts about you. Come on and we’ll bowl down along.”

‘“Right,” says I, and made a move to go, but couldn’t stir a leg. What was it but when I pulled the door behind me the tail of my coat got caught in it, and there I was stuck like a spider to the wall. Wasn’t that a nice pucker to be in! If it was raining soup it is a fork I’d have!

‘“Have you e’er a match?” says I sparring for wind.

‘Decent enough he handed me a box of ’em. I began cutting a bit of tobacco to put in the pipe, all the time racking my brains for a way out of the pucker. With that there was an almighty crack of thunder that nearly rent the heavens.

‘“It’ll make a dirty night,” says I, “and your best plan now’d be to run along home to the little woman for she’ll be frightened.”

‘And they do – about the only thing they’re frightened of! That put the skids under him and off he went. Up here you want it, down below for dancing! When he was gone I bent down to try to disentangle myself out of the door when I heard a voice behind me. “You didn’t give me back my matches,” says he.

‘Oh a mean man, that same DI. I was back stonemasoning the following week.’

Going to the Train

The young people going away to America would contribute too to the general hilarity and I remember that night Mick the fiddler told the story about his father and the three travelling tailors.

At that time poor people could only afford meat once a week. And before that again there was a time in the history of Sliabh Luachra when people could only have meat three times a year, at Christmas, Easter and Shrove Tuesday night.

One Sunday Mick the fiddler’s father was sitting by the hearth. The spuds were done and steaming over the fire, and at the side of the fire, nesting in the gríosach, was a small pot, the skillet. In the skillet was a piece of imported bacon called American long bottom bubbling away surrounded by some beautiful white cabbage. For a whole week the poor man had been looking forward to this hour. And you wouldn’t blame him if his teeth were swimming in his mouth with mind for it. His wife Mary was laying the table when the front door opened and in walked three travelling tailors, ravenous.

D’réir an seana chultúr, ’twas share and share alike. Already Mary was putting out three plates so that the man had to think quick. Mick the fiddler himself was only a small child of about a year and a half running around the floor in petticoats. They wouldn’t put any trousers on a little boy at that time until he was five – people were more practical. The father picked him up and began dangling him that way.

‘He didn’t dance and dance, he didn’t dance all day, he didn’t … ’ When the tailors weren’t looking he whipped a big spud out of the pot and then attracting the tailors’ attention he let the spud fall from under the child’s clothing into the cabbage and bacon!

You’d travel from here down to see the look on the tailors’ faces.

‘I’m afraid,’ says he, letting down the child … ‘I’m afraid it’ll be spuds and salt all round … Of course Mary and myself could eat the bacon. After all the child is our own!’

It was common at the time to give those going away a little present. Maybe a crown piece or a half-sovereign. Happy indeed’d be the one that’d get a golden guinea. As well as that the girls might get wearables. A pair of gloves or the like, and it was usual to give the men a silk handkerchief. You’d see ’em sqeezing it and on opening their hand if it bounced up it was pure silk. Of they’d throw it at the wall and if it clung to the mortar it was the genuine article. And you’d see those handkerchiefs the following morning waving from the train as it went out of sight under the Countess’ bridge.

In the morning the horses’d be tackled, and anyone who could afford it’d go to the station. Often I was there as a child. At that time it would take the young man going to America eight to ten days to get there in rickety old ships – you could feel the motion of the waves under your feet. And then when he landed over in New York he’d have to work very hard to put the passage money together to bring out his brother. That’s how ’twas done. John brought out Tim and Tim brought out Mary. Maybe then he’d get married and have responsibilities, so when again would that young man standing there … when again would he come back over the great hump of the ocean … if ever.

He’d be surrounded on the platform by his friends, and when the time came for him to board the train he’d start saying goodbye to those on the outside of the circle, to his far out relations and neighbours, plenty of gab for everyone, but as he came in in the circle, to his cousins, to his aunts and his uncles, the wit and the words would be deserting him. Then he’d come to his own family, and in only what was a whispering of names, he’d say goodbye to his brothers and sisters. Then he’d say goodbye to his father, and last of all to his mother. She’d throw her two arms around him, a thing she hadn’t done since he was a small child going to school, and she’d give vent to a cry, and this cry would be taken up by all the women along the platform. Oh, it was a terrifying thing for a small child like me to hear. It used even have an effect on older people. Nora Kissane told me she saw a man running down the platform after the train so demented he was waving his fist at the engine and shouting, ‘May bad luck to you out ole smokey hole taking away my fine daughter from me!’

And there was a widow that worked her fingers to the bone to get the passage money together to send her son to America. A rowdy she wasn’t going to be sorry after. A useless yoke, nothing for him but his belly full of whiskey and porter when he could get it, singing in the streets until all hours of the morning. A blackguard that put many a white rib of hair on his mother’s head and took three young girls off their road. The devil soften ’em. They were worse to let him.

The woman was not going to go to the station at all to see him off, but when she saw the other women going she said she might as well. And then when she saw how lonely the parents were parting with their children she thought, ‘They’ll think me very hard-hearted now if I don’t show some concern.’ And of course when her heart wasn’t in it she overdid it. She went over to the window of the train he was standing inside in the carriage, and throwing her hands to heaven she said, ‘Oh John, John, John, don’t go from your mother! Don’t go away, John. Oh you sweet, utter, divine and lovely little God sitting above on the golden cloud why don’t you dry up the Atlantic ocean so the ship couldn’t sail and take my fine son away from me. John, John, don’t go from your mother, John!’

He opened the door and walked out saying, ‘I won’t go at all, Mother!’ He went down the town and into the first public house and drank his passage! You heard the singing in the street that night!

Pegg the Damsel

Choo chit, choo chow, choo chit, choo chow, choo chit, choo chow. Choo, choo, ch … ch … ow! Ch … ch … sssssh! Cork! Glanmire Station. Cork!

Whatever part of Ireland you left that time going to America you’d have to pass through Cork and then down to Queenstown.

Over here for the boat train. Over here all those for Queenstown. All aboard the boat train! Mind your coat in the door there! All aboard! Choo chit, choo chow. Choo chit, choo chow.

In the morning they’d go out in the tender, out the harbour to where the ship was waiting. They’d go on board and sail away, and the last thing they’d see – often I heard those who came back remark on it – the last sight of home was the Skelligs Rock, the half-circle of foam at the base of Sceilig Mhichíl.

Now that they were gone the people at home sat back … and waited for the money! The first Christmas cards we as children saw came from New York. They had lovely drawings of St Joseph and the Holy Family, but lovely and all as those drawings were they couldn’t hold the candle to the picture of George Washington – and if George Washington or General Grant weren’t inside the crib with the Holy Family there wouldn’t be much welcome for the Christmas card. Indeed I heard of one man who used cut open the letter, shake it, and if a few dollars didn’t fall out he wouldn’t bother reading it! What bank would change a Christmas card!

But to be fair the money nearly always came to the mother. It was the indoor and outdoor relief – the dole, grant and subsidy of the time. She would put it to good use. It would go to buy the few luxuries they’d otherwise have to do without at Christmas. It would go to improve the house, to put extra stock on the farm, to educate a child – where did the civil service come from! And as people got old the money’d go to take out the appendix or to put in false teeth!

Anyone that ever went the road to Killarney couldn’t miss Pegg the Damsel’s slate house. ’Twas at the other side of the level-crossing, and you couldn’t miss that either, for any time I ever went that way one gate was open and the other gate was closed – they were always half-expecting a train!

Pegg’s house was done up to the veins of nicety. Dormer windows out on the roof, variegated ridge-tiles, walls pebble-dashed – what you could see of ’em – for they were nearly covered with ivy. In the front garden she had ridges of flowers, surrounded by a hedge, beautifully clipped, you may say the barber couldn’t do it nicer, and one knob of the hedge left rise up, and trained to give the effect of a woman sitting down playing a concertina – Pegg herself, of course, for she was a dinger on the box! I tell you if you heard her playing the Verse of Vienna, you’d never again want to turn on the wireless. How is this she had it!

Father Walsh’s, Father Walsh’s,

Father Walsh’s top coat,

For he wore it and he tore it

and he spoiled his top coat.

Diddle dee ing dee die doe,

Diddle dee ing dee die dee,

Diddle dee ing dee die dee,

Diddle dee ing dee die doe.

She was brilliant! Of all the posies in Pegg’s garden the roses took pride of place. She had ’em there of every hue – June roses, tea roses, ramblers and climbers. Now, at the back of Pegg’s house there was a farmer living called Ryan, and he had a goat running with the cows. And a very destructive animal he was too. He came the way and he knocked into the garden and he sampled the roses, and he liked ’em, and he made short work of ’em!

Pegg complained the goat to Ryan. ‘And what do you want him for?’ says she, ‘with ten cows, sure ’tisn’t short of milk you are!’

‘Ah, ’tisn’t that at all,’ says Ryan, ‘goats are said to be lucky, and another thing they’ll ate the injurious herb and the cows’ll go their full time – if ye folly me? You needn’t be in Macra na Feirme to know that!’

‘You’ll be doing full time,’ says Pegg, ‘if that goat don’t conduct himself, for I’ll have you up before the man in the white wig.’

‘Play tough, now,’ says Ryan, a man afraid of his life of litigation, for it can lighten the pocket. ‘I’ve a donkey chain there and I’ll shorten it down to make a fetters for the goat.’

Which he did! But when the goat got the timing of the chain, like the two lads in the three-legged race, he was able to move as quick with it as without it.

Now, that was the same year Pegg married the returned Yank … or was it? ’Tis so long ’go now … everything is gone away back in my poll. ’Twas! A man that went in a fright for fancy shirts – and they do. One day is all he’d keep the shirt on him. Look at that for a caper! The poor woman kept going washing!

This morning she rinsed out his red shirt and put it outside on the hedge to dry. That was all right, no fault until the goat bowled the way, and handicapped and all as he was, he broke into the garden – attracted by the colour, I suppose! And Pegg the Damsel opened the front door just in time to see the white button of the left cuff disappearing down the goat’s throttle.

There was no good in calling the Yank. He was in blanket street waiting for the shirt to dry! All night work he had in New York and he used to sleep during the day, but as he had no night work here he used to sleep day and night!

She chased the goat with the broom and he made off up the railway from her. He ran down the slope and when he was crossing over the tracks, well, ’twouldn’t happen again during the reign of cats, didn’t one link of the chain go down over the square-headed bolt that’s pinning the rail chair to the sleeper. He was held there a prisoner, he couldn’t lead or drive, and what was more he heard the train whistling – ’twas coming now. Wasn’t that a nice pucker for a goat to be in, and if I was there and if ye were there, we’d lose our heads, but the goat didn’t. What did he do? He coughed up the red shirt and flagged down the train!

Shrovetime

Pegg’s Yank, the man in the red shirt, came home on a trip and made a match with Pegg. Pegg was a monitor – well a junior assistant mistress – so he had jam and jam up on it!

A lot of young people going away at that time looked upon America as a place or state of punishment where some people suffered for a time before they came home and bought a pub, or a farm or married into land or business … like Pegg’s Yank. A fair amount succeeded. If you walked around the country forty years ago every second house you’d go into either the man or his wife had been to America.

Many is the young woman came back – well she wouldn’t be young then after ten years in New York, but young enough! – and married a farmer, bringing with her a fortune of three or four hundred dollars. Then, if the farmer had an idle sister – and by idle there I don’t mean out of work! – the fortune was for her. Then she could marry another farmer, or the man of her fancy, that’s how the system worked, and that fortune might take another idle sister out of that house and so on! So that the same three hundred dollars earned hard running up and down the steps of high stoop houses in New York city could be the means of getting anything up to a dozen women under the blankets here in Ireland! And all pure legal!

There was no knowing the amount of people that’d get married at that time between Chalk Sunday and Shrove Tuesday. But quare times as the cat said when the clock fell on him, no one at all’d get married during Lent, or the rest of the year. So, if you weren’t married by Shrove Tuesday night you could throw your hat at it. You’d have to wait another twelve months, unless you went out to Skelligs where the monks kept old time. Indeed a broadsheet used to come out called the Skelligs List – it used be shoved under the doors Ash Wednesday morning. Oh, a scurrilous document in verse lampooning all those bachelors who should have, but didn’t get married during Shrovetime.

There’s Mary the Bridge

And Johnny her boy friend,

They are walking out now

For twenty-one springs!

There’s no ditch nor no dyke

That they haven’t rolled in –

She must know by now

The nature of things!

‘Oh, Johnny,’ says she,

‘Do you think we should marry

And put an end for all time

To this fooster and fuss?’

‘Ah, Mary,’ says he,

‘You must be near doting.

Who do you think

Would marry either of us!’

Who indeed! But the matchmaker was there to put the skids under ’em. That’s one thing we had in common with royalty, matchmaking – of course the dowries weren’t as big!

Why then there was a match made for myself one time, and it is so long ago now that I won’t be hurting anyone’s feelings by telling ye the comical way things turned out.