Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

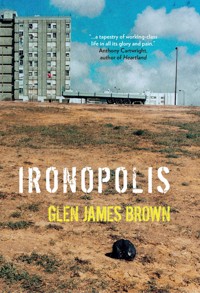

Stranded on the outskirts of Ironopolis — nickname to a lost industrial Middlesbrough — the Burn Council Estate is about to be torn down to make way for regeneration. For the future ... But these streets know many stories, some hide secrets … Jean holds the key to the disappearance of a famous artist … Jim's youth is shattered during the euphoric raves of '89 … A brutal boyhood prank scars three generations of Frank's family … Corina's gambling addiction costs her far more than money … And Alan, a man devastated by his past, unravels the darkness of his terrifying father, a man whose shadow has loomed large over the estate for a lifetime. And then there is the ageless Peg Powler, part myth, part reality: why is she stalking them all? 'Human nature? Class politics? Whatever it was, it wasn't us … Deep down we were part of a whole, single energy, and all we had to do was be ready to sink down together.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 598

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

IRONOPOLIS

GLEN JAMES BROWN

Parthian, Cardigan SA43 1ED

www.parthianbooks.com

First published in 2018

© Glen James Brown

ISBN 978-1-912109-14-2

Edited by Edward Matthews

Cover design by Syncopated Pandemonium

Section Title Page Icons made by Freepik from www.flaticon.com

Glasses icon on Midnight title page by Allison Love @friendfriend.net

Printed in EU by Pulsio SARL

Published with the financial support of the Welsh Books Council

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A cataloguing record for this book is available from the British Library.

For you, Sue

CONTENTS

DAY OF THE DARK

(Una Cruickshank of Loom Street)

THIS ACID LIFE

(Jim Clarke of Hessle Rise)

MIDNIGHT

(Frank and Scott Hulme of Second Avenue)

HEART OF CHROME

(Corina Clarke of Peelaw Bank)

UXO

(Douglas Ward of Campbell Road)

THE FINAL LEFT

(Henry Szarka of Sober Hall)

I believe that if we have a few more years at our disposal,

we shall have the best housing record of any nation in the world.

Aneurin Bevan, 1948

DAY

OF THE

DARK

Una Cruickshank of Loom Street

25/2/1991

Dear Stephan,

Once, as a girl on holiday in Blackpool, I went on the Wild Mouse, this ride where you squashed into a fibreglass mouse that went screaming round a rickety wooden track. Never, ever again. Afterwards, I had to clamp head between knees to keep my candyfloss down, then spent the rest of the day holding the coats. You’ve probably never heard of the Wild Mouse, so maybe this wasn’t the best way to start, but that was what reading your letter felt like.

In answer to your first question: yes, your ‘detective work’ was good. I still can’t believe you went through the marriage records and wrote to everyone in the country with my old name. God knows what the ten other Jean Healys will make of this! I’m also struggling to wrap my head around the fact that Una named a painting after me. After what happened between us, I always wondered if she still thought of me. I suppose that answers that. I’ll answer your questions about her as best I can, though I don’t know how useful I’ll be or how long it’ll take. I’m not well you see, but I won’t bore you with the details. The only thing drearier than illness is having to listen as others describe theirs.

You asked about when me and Una first met. Well, from the very beginning she was always around. Like I remember watching ants chew the legs off a woodlice (louse? I never know which) in the back yard, a line of ants carrying them away still twitching down a crack. Another time, I’m standing in the kitchen door with warm piddle running down my legs as Mam, her mouth full of wooden pegs, hangs the washing. I remember drowning my dolly Pree in a rain-filled pothole. I’ve got many raggedy shreds of sight and sound like that deep inside me, and in all of them Una is there somewhere, just out of frame.

Later, things get clearer: me and Una on the kerb tearing one of Mam’s jam tarts apart with four hands. I see her twisting and popping her elbows to make the other Loom Street kids squeal (she was the most double-jointed person I’ve ever met). I remember sitting behind her in the bath as Mam tips soapy water over her head. Greasy black hair unkinking. Suds slipping down her spine. Back then you could still bathe another woman’s child.

Una had no siblings but I had a sister, Agnes, five years older than me and pretty and popular and everything I wasn’t. Plump, I suppose you would have called me (Agnes’ name for me was ‘suet’). I was shy, got picked on, and was convinced Mam loved me less because of it. Una would say, ‘Sod Agnes, I’m your kin,’ and at nights as I lay in bed listening through the wall while Mam did Agnes’ hair, or pinned her a new dress, the two of them giggling away, I told myself it was true.

Then as now, kids like us didn’t get an easy time at school. To give you an example I want to tell you about a specific P.E. class. Mr Thirsk was our teacher then, so we must have been eight or nine. I hated P.E. Whenever I think of those lessons now I see rain-filled skies, dead leaves skittering round my ankles. Nitheringly cold, too, our flimsy P.E. kits no match for the wind shrieking off the North Sea. School was split into houses based on history: The Stewarts were green, Hanover was red, Windsor blue, and yellow was The Tudors. I was a Tudor, Una a Stewart, and we were playing against each other in a netball match. Netball terrified me because I thought if I caught the ball wrong I’d break my fingers. But Una was fearless: tall, stick-thin, lightning quick, spinning on her heel as she threaded the ball through waving Tudor arms. Elsie Stanger hated Una especially. Elsie was my team captain and worst bully, who had once squirted ink into my jam roly-poly and made me eat it. All through the game she’d been rolling her eyes and sniggering whenever I made a mistake (which was often) and as for Una, she stood on her heels and jabbed her in the back whenever Mr Thirsk wasn’t looking. I heard Elsie hiss ‘your mam’s a crazy gypsy’ as she and Una tussled for the ball, and as the game went on, Una’s pale face darkened in a way that had nothing to do with exertion.

Near the end of the game, Una got the ball in the centre circle and Elsie saw her chance. She charged full tilt at Una with no intention of trying to win possession. No, Elsie wanted to flatten her. Una ignored her Stewart teammates as they yelled for her to pass, to save herself. Instead, she wound up and whipped the ball directly at Elsie’s face. At almost the same second, a black streak shot across the playground and the ball exploded in a burst of feathers and an ear-splitting screech. Elsie, too, screeched as she tripped, skinning her hands and knees on the rough tarmac.

Stillness. Mr Thirsk blew his whistle. The rest of us blinked at each other.

The sparrowhawk lay smashed on the playground, one wing twisted under itself, the other unfurled and twitching. Its head was bent awfully to the side and a single golden eye stared up at us. The poor thing wasn’t dead. Dappled brown feathers blew away in the cold wind. A few feet away, Elsie held her bloody knees with her bloody hands and whimpered. I didn’t envy her. Her mam would be digging stones out of her with a hot pin for weeks.

‘Take her to the nurse,’ Mr Thirsk said. You could tell he wasn’t sure what had just happened either.

Two girls hoisted Elsie up under her armpits and limped her away. Una stood in the centre circle alone, staring at the dying bird. Mr Thirsk blew his whistle again, and it sounded so thin and stupid against the wind. Lesson was over, he said, so we all headed back to the stinky cloakroom to change. The others in the class were whispering about Una and throwing suspicious glances over their shoulders at her. I turned back when I got to the door. Una was still on the playground, kneeling over the hawk. It looked like she was speaking to it. Then she wrung its neck. When she came over she had two feathers in her fist. She handed me one.

‘Keep this,’ she said.

Her eyes were pink, but dry. That was another thing: I never saw her cry. Actually, that’s a fib. I did once, but many years later.

That sparrowhawk set the tone for Una at school. It was the beginning of the myth that grew darker and stranger the older she became. A myth which made girls like Elsie think twice before they messed with her. Because of this, I stayed as close to Una as I could. I included myself in her protective bubble, and while I may have succeeded, it meant the few other friends I did have soon drifted away. Until all me and Una had were each other.

So those are my earliest memories. My hand is cramping now. Can’t write anymore. I’ll post this tomorrow. I’m aiming to answer the rest of your questions as soon as I can, because I feel there’s a lot more to come. You’ve jarred something loose, though whether that’s good or bad, I can’t say.

Sincerely,

Jean Barr

P.S. You said you’re the boss of Ananke Acquisitions? Please send me the address, so I can direct future letters there. I’d prefer my husband not to wonder why I spend my days writing to another man. Things around here are tense enough as it is.

6/3/1991

Dear Stephan,

You also wanted to know about her parents? Well, I’ve been sitting here all morning attempting to do just that but it’s beyond me. Instead, I’ll tell you about New Year’s Eve 1958, and let it stand for all.

Even though you didn’t get presents, I loved New Year’s Eve better than my birthday or Christmas or anything. I think it was because everybody was the best version of themselves. People wore their best clobber and nicest perfumes. They had a drink, cracked a joke, and dropped their guards. It was wonderful to see. Teesside was a metal town back then, Ironopolis folk called it: over 40,000 people worked at the forges in their heyday, and the night skies burned red. But graft could be brutal. It could – and frequently did – swallow people whole, but for that one night everybody was changed. Our neighbours, but not.

We always threw a big party at our house for anyone who wanted to come. No invitation necessary. It was the only night of the year where we extended the dining table and Mam’s special red and gold tablecloth came out. Seeing that cloth was like seeing an old friend. I was eleven, and I’d spent the whole day helping to make the food: sausage rolls, ham and pease pudding stotties, brandy snaps (bear in mind this was only four years after rationing and food like that was still the height of sophistication). I can still smell the Yardley’s English Lavender and Old Spice and cigarette smoke as I walked through the party with trays. I loved how people sneaked looks at their watches, as if midnight was a big secret only they were in on.

I was also on coat duty, which I took seriously. I’d say, ‘Good evening Mr and Mrs So-and-So,’ trying to do my best radio voice, ‘do come in.’ There was a knock at the door but it was only Una. Her hair a violent charcoal scribble around her ghost face, those dark, taciturn eyes. I let her in without launching into my welcome-spiel.

‘They’re coming,’ she said as she passed me.

I peered up Loom Street at the rapidly approaching figure of Talitha Cruickshank – Una’s mother – clip-clopping towards me in a black dress and shawl that hung like a dead thing off her collarbones, her cleavage spilling out when she bent down to me on the front step. Her eyelashes were clumped together with mascara and her red painted mouth was a stab wound pressed hard to my cheek until I felt teeth. No perfume either, not like the other ladies. She reeked of sweat and her breath smelled like fruit turning black.

She raised her left hand, which was missing the ring finger, to the ceiling. ‘The end is nigh,’ she whispered. Never forgotten that. Then she said George would be along in two ticks, and with that she went into the party.

I shivered in the open doorway, straining my eyes up the street, but I couldn’t see him. Maybe he’d forgotten something and gone home? Maybe he’d already come in through the back door? Like I said, I took my guest-welcoming seriously, but the December air was breadknives. I decided to keep the door open a crack just in case, and was in the process of wedging a shoe in the jamb when I saw him.

George Cruickshank came down the walk like a man in syrup. Shoe heels scraping the frosty path, arms loose at his sides. Minutes passed before he reached the house and my teeth rattled the whole time.

‘Good evening, Mr Cruickshank,’ I said when he finally arrived.

It took him a moment to realise where the voice was coming from. He looked down at me with watery eyes, and if you’d never met him before you’d think it was booze. But not me, I knew better.

‘Hello, lass.’ George pulled the words out like toffee.

‘Your tie’s untied, Mr Cruickshank.’

He put an unsteady hand on my head, but the tie remained loose around his throat.

When the party got off the ground I was allowed to play my favourite records. They’re still in the loft somewhere: ‘Tom Hark’ by Elias and his Zigzag Jive flutes, and ‘Endless Sleep’ by Marty Wilde. (I still shiver when Marty sings: ‘I heard her voice crying in the deep / come join me baby in my endless sleep’.) Dad and Uncle Neville had humped the settee onto the upstairs landing that morning, so there was space to cut a rug, and everybody was having fun. (I’ve got a diamond-edged memory of walking in on Mam and Dad kissing over the kitchen sink. When she saw me, Mam giggled and threw a tea-towel over Dad’s head.)

Meanwhile, Talitha worked the room. She touched men’s arms and laughed too-loudly at the things they said, while the wives of those men shot dark looks at each other. George sat on a stool against the wall with an untouched drink in his hand, lost in a spot on the carpet. I found Una upstairs on the settee with what looked like a glass of bitter lemon, but when I had a sip my mouth filled with spit.

‘Gin in it,’ she said, and popped her elbows.

Agnes shouted up the stairs that it was nearly midnight, so I pulled Una off the settee and we went down.

The last moments of the year are always the most exciting, don’t you think? Someone lifted the needle off the record and snapped on the wireless, swizzling through the flying-saucer noise to the BBC announcer telling us we only had thirty seconds left. The adults bustled happily into a rough circle and crossed their arms, while the kids still on their feet at that hour formed another, smaller, circle inside theirs. I found myself across from Una, who was, I think, sozzled.

‘Ten,’ the announcer said.

TEN! – Everyone roared – NINE! – I mumbled – EIGHT! – Una didn’t say anything – SEVEN! – The woman next to Talitha held her hand like you would a stranger’s used hanky – SIX! – I looked around for George – FIVE! – he wasn’t there – FOUR! – I caught a glimpse of him through the bodies, still on his stool, watching as his spilled drink soaked into the carpet – THREE! – TWO! – ONE! – HAPPY NEW YEAR!

The adults shook limbs to ‘Auld Lang Syne’, while we bairns substituted the words for ‘daaaah daaaah dah dahs’ while trying to yank each other’s arms out of their sockets. Una put up no resistance. Her arms jerked painfully, her head bounced loose on her long neck. The adults broke apart, hugged and kissed and shook hands, and everything was perfect until an off-kilter wail silenced the room. Talitha had turned off the wireless. She clasped her hands between her breasts and stared with wild eyes. People instinctively gave her space, as you would a dog you don’t trust. Someone tutted loudly.

Then Talitha smiled a wide, smoke-wrecked smile, closed her eyes and began to sing.

To this day I’ve never heard the like. How can I, with only this notebook and pen, begin to describe it? It was treacly and curdled and jagged all at once, and not in English. Smirking men elbowed each other while others (women, mostly) just glowered. Una slinked back upstairs with a freshly pilfered drink.

Talitha herself noticed nothing. She sang and swayed in the centre of the room like an animal caged so long its mind’s gone, and only after the final trembling note faded did she open her eyes. Her mascara had run into mad black blurs like the ink-splot pictures they have at the loony bin.

The room was deadly silent until Mam led a half-hearted smattering of applause. Someone put a record on and the tension lifted a little. George’s stool was empty. I went to the hall and the door was wide open, letting in the now-January bitterness. George himself was some way off up the street, shuffling away like an iron-booted diver across the seabed.

Back in the living room, Talitha was involved with some neighbours. I was out of earshot, but I could tell backs were up. Mary Eastbourne from Number 8 jabbed a finger at Talitha, who was grinning a grin laced with chaos. Mary lunged at her, but was held back. Mam stepped in and said something to Mary, who shook herself free and stormed into the kitchen. Then she spoke directly into Talitha’s ear. I watched as Talitha’s grin faded to an eerie Elvis lip hitch. Una’s mother elbowed through the party towards me. I ran into the hall and opened the front door for her.

Talitha tugged her thin shawl across her shoulders. ‘Everyone’s a critic,’ she said as she left.

Upstairs, Una’s new drink was almost sunk. I said Happy New Year and she slurred it back. She smelled like unwashed bedsheets when I hugged her, and had to close one eye to focus on me.

‘There’s a kiss on your cheek,’ she said as she passed out.

*

So those were her folks, Stephan. Make of them what you will. Next time I’ll tell you about the riverbank. I know you are eager for me to get to that.

Sincerely,

Jean Barr.

29/3/1991

Dear Stephan,

There’s a racket downstairs. Vincent is shouting at Alan for not putting the washhouse key back on the hook. Alan is my son, Vincent my husband. Now I can hear Alan limping upstairs and shutting his bedroom door. Chopin – that’s our dog – howls outside. Vincent stomps around. Now he’s gone out and it’s quiet.

I apologise. I didn’t mean to tell you any of this, it’s just it happens a lot. Alan is twenty-two and sensitive, something which Vincent finds difficult to accept. But then, you know about art, Stephan. I don’t need to explain sensitivity to you.

Una was a born artist. Even as a bairn, she’d find some way to leave her mark – even just with her finger on a steamy bus window. Here’s a story for you: one rainy weekend when we were about ten and mooching around the house – always my house – we saw Nana had nodded off in her chair. Una clocked her first, and went to the battered old sea chest my Dad still had from the war, where I kept my toys. She creaked the lid, got pencils and paper and stretched herself out on the hearth rug. Turning her head this way and that, sucking on the end of her pencil, she studied Nana. Then she started to draw. Her pencil scratched like mice in the walls, her eyes shining in their inkwell sockets.

I didn’t want to be left out, so I got paper of my own, but when I looked at Nana…where did I start? The head, I supposed. Ms Fox in art class said that a face was a crucifix inside an oval, but Nana’s face wasn’t an oval. It wasn’t any shape I could see. I glanced over at Una’s page. Already, Nana was beginning to appear: her but not her, less the lines themselves but the spaces between them. I began my own drawing slowly. Each tiny, tentative stroke I made took me further from the picture in my head.

Una’s blunted pencil rolled from her fist. ‘Her ears are weird,’ she whispered.

Her picture was…stunning. Proper art at ten years old. I tried hiding my own scrawl, but she tugged it from me with pinched fingertips.

‘Don’t,’ she said.

Nana woke herself up in the usual way, by breaking wind. She always said the same thing: ‘Oh deary me.’ It creased us up, that. She wanted to know what mischief we were up to, and demanded we hand over our drawings. She held mine up to the window. The rain clicked softly against the glass.

‘Oh, this is lovely,’ she said. ‘Just lovely.’

I could see my stupid drawing through the paper and said nothing.

Then Nana looked at Una’s page and something passed across her face. She peered over the paper. Had Una drawn this just now?

Una nodded.

Nana looked at the page for a long time. ‘I’m old, aren’t I girls?’ she said.

We said she wasn’t, but I suppose she was.

Nana pinned our drawings on the wall above my sea chest, where they remained for many years, long after things had gone bad between the two of us. I would see them every day – an awful reminder of why they had.

*

When you said in your letter that Una had painted hundreds of the same scene, I knew exactly which one you meant. She used to do that riverbank over and over again. At first, I’d thought it was the river Tees, but later knew it wasn’t. I can still see it: the black mud, the rustling reeds. The way you couldn’t tell where the fog ended and the river began. Sometimes there would be shapes in the fog, just out of focus, or mostly off the page, but Una would never say what – or who – they were.

You asked if I knew why she was ‘fixated’. Well, Ms Fox asked Una the same question after she had, for the umpteenth time, spent the lesson on her swirling blue-grey riverbanks. Una replied that it was a dream she had, actually the only dream she ever had. Ms Fox looked at her funny when she said that.

There’s more to say about this, and it’s to do with the Green Girl, but I can hear Chopin howling. That means Vincent’s back, and I won’t be able to relax until he and Alan have made peace. That’s still my job, for now at least.

Sincerely,

Jean

P.S – No, I don’t have any of her early work, sorry. Who knows where those pictures are now? Where does anybody’s childhood go?

10/4/1991

Dear Stephan,

You wanted to know who the Green Girl was in that one painting you described. Well, you’re in luck.

Apart from art, the other thing Una loved was giving herself the heebie jeebies. Every other Wednesday, a man called Henry drove the mobile library down Loom Street and Una checked out as many ghost stories as her ticket allowed. Spooks floating down corridors, The Thing in the Cellar, those mad Victorian photos of ectoplasm coming out of the gypsy woman’s eyes – Una ate it up.

Her favourite stories, though, were about being buried alive. You would not believe how often hospital patients used to wake up six feet under after some sackless doctor declared them dead, their long-buried coffins finally exhumed to show scratch marks on the inside of the lids. Or renovators turning an old castle into a swanky hotel knock through a wall and the mouldy bones of some bricked-up so-and-so rattle out. Or explorers going into an ‘uncharted’ South American cave system, only to find in the most inaccessible antechamber two human skeletons curled together like quotation marks.

Una’s absolute favourite was about the luxury cruise liner that made a mysterious clanging below decks. Engineers combed the whole ship top to bottom but couldn’t find the source. Years passed and the clanging got worse, got into the pipes, started echoing through the entire ship to wake up First Class, which was the last straw because once posh people got the hump, you knew about it. Unexplained fires began breaking out. Food supplies went rotten. A cabin boy was washed overboard by a freak wave on an otherwise calm sea. Word got around about the cursed cruise liner, and people stopped booking passage. Eventually the ship was scrapped.

Una had told me the story a dozen times, but still gripped my arm for the last part: ‘and it’s only when they prise the hull open that they find the riveter who went missing all those years before, during the ship’s construction. Still in his overalls, mallet still in his bony hand. He’d been working in the hull when it was sealed up and nobody heard his cries for help. That’s what the clanging was! His ghost hammering let me out! Let me out!’

Una was fascinated by what might have gone through the head of that doomed riveter during the days it must have taken him to die.

‘He must have realised things,’ she said to me once.

‘Like what things?’

Una was serious. She leaned close so her lips brushed my ear. ‘Like…BOO!’

Books aside, Nana was best for giving us the creeps. Whenever me and Una got too rambunctious for our own good, or didn’t come back for tea on time, or ran our gobs during Hancock’s Half Hour, she’d say, ‘If you don’t mind yourselves, Peg Powler will get you.’

Peg Powler, as Nana never tired of telling us, was a witch who lived in the river Tees and drowned boys and girls who didn’t listen to their elders and betters.

‘But we don’t live on the river,’ we’d say.

Nana was ready for that. ‘Peg’s in the pipes,’ she’d say. ‘She’ll drag you down the netty (toilet to you, Stephan) by your bum.’

Usually, that was as far as the Peg stories went, but one day, when we must have been being particularly flippant, Nana said: ‘Oh, so you think I’m having you on, do you? Did I ever tell you about how she almost got me?’

Mesmerised, Una plonked herself down at Nana’s feet.

‘I was about your age,’ Nana said, her eyes turning to Una’s drawing above the sea chest, ‘a long, long time ago now. I lived in a place called Foulde, not far from Egglescliffe, right on the Tees. Back then there were none of these awful council estates. We weren’t all squashed up like we are now.’

‘Was it a farm?’ Una asked.

‘No, lass. Not a farm, but there was nature all around. Real dirt under our feet. We knew all the stars. I’ll bet you girls don’t know any stars.’

Which was true. Then as now, whenever I look up, all I see is orange. Missing stars were just one of the ways Nana complained about the Burn Estate. She often reminisced about how the good people of Foulde (and later St Esther, where she moved with Granddad) were told by the powers that be that their homes were in fact slums not fit for human purpose. It was an injustice, Nana said, made worse by those communities being split up and forced into ‘these bloody cement chicken coops.’ Whenever Mam and Dad were in earshot of this kind of talk, I’d catch them rolling their eyes at each other.

But back to the story. ‘Anyway,’ Nana went on, ‘my Mam – that’s your great Grandma – she used to warn us bairns against Peg Powler, just like I’m warning you lasses now. And just like you two, we paid her no mind. Peg Powler? Haway, that’s babby stuff. So of course, one sunny day we all trotted off down to the river to play…’

Me and Una held each other on the hearth rug.

‘If memory serves,’ Nana said, ‘it happened just past Egglesciffe, where the river bends towards Yarm. We were messing about, skimming flatties and catching sticklebacks in jam jars, when my brother Bill said we should play hide and seek. He counted while the rest of us scattered. I went the opposite way to everyone else, and found a willow tree growing out over the river. The dangly leaves came down and met the reeds to make a sort of veil around me. Its roots were just above the water, so I clambered down onto them and ducked. It was a good hiding place and soon, in the distance, I heard my friends screaming as Bill caught them. I remember thinking, “I’m going to win!”’ Nana leaned forward in her chair. ‘But then a cold feeling crept over me. I was being watched. I looked down and the river was going white. Mam had warned me about Powler’s Cream. It meant she was close…’ she glanced at the clock. ‘Oh, I think its teatime girls.’

‘NO!’

Nana flashed her dentures. ‘Sure?’

‘YES!’

We settled back down and Nana carried on.

‘So,’ she said, ‘I was looking at the cream when Peg appeared. All I could see of her was her head above the water. She had a hand like this’ – Nana splayed her hand over her face and glared at us through arthritic fingers – ‘and she was looking right at me.’

Una dug her filthy nails into my arm.

‘I couldn’t move,’ Nana said, ‘couldn’t speak. I was in some kind of trance. I could hear her in my head, calling my name, and the more I listened, the more I wanted to go to her.

‘Then she took that bony claw away, and I’ll tell you, girls, I never want to set eyes on another face like that as long as I live. Her skin was a sickly green stretched so tight you could see her skull. Black hair plastered down the sides of her head, and there were wriggly things in it. Worms and parasites, God knows. You could see her workings under what little flesh she had left – the bones, sinews, tendons. And the smell. Can you guess what she smelled of?’

We shook our heads.

‘Mildew,’ Nana said. ‘She stank so bad I couldn’t breathe. When she smiled her teeth were like broken bottles.’ She shuddered at the memory. ‘But do you know the worst thing, girls?’

Whisper: ‘What?’

‘She was beautiful.’

I didn’t understand. How could someone so terrible looking be beautiful?

But before I could say anything, Una spoke. ‘So what did she do?’

‘Peg? She got closer and closer. I tried to move, scream, but I couldn’t. I wet myself. My foot started slipping off the roots. It all happened so slowly, and her eyes – oh God girls, those eyes – they never left mine. When she was close enough, she reached out and her long slimy fingers closed round my ankle. They were so, so cold. Cold and dead. And that’s when I heard Billy shouting my name from the top of the bank. Somehow his voice did something, broke the spell. I tried to scramble away, but Peg tightened her grip and started sinking. She wanted to take me down into the water with her.’

Una’s leg jiggled against mine.

‘I was in up to my knees, girls, I was this close,’ Nana leaned forward in her chair, holding her thumb and index finger a centimetre apart, ‘this close to letting her have me. But then I thought of Billy and Mam and Dad, how I’d never see them again, and I yanked my leg as hard as I could and suddenly I was free. I staggered through muck and reeds and collapsed on the bank just down from Billy and the rest of my friends. Bill was white as a sheet, bless! My shoe was full of blood. She’d taken a chunk out of me.’

I glanced over at Una. Her fists were balled.

‘I never played on the river again,’ Nana said. ‘I knew Peg had the taste for me.’

‘Did you ever tell?’ Una whispered, awed.

‘I told everyone! Even Mam and Dad. I didn’t want Peg getting anybody else, did I?’

‘Did they believe you?’

‘Why not likely. Me and Bill both took a hiding, and my friends thought I was soft in the head.’ Nana worried a loose thread on her skirt. ‘Anyway, shortly after, Bill got pneumonia and died…I didn’t feel much like playing after that.’

‘I’m sorry, Nana.’ I said. I didn’t know what I was supposed to say.

‘It was a long time ago, hin.’

A silence. Then, me: ‘Nana?’

‘Aye?’

‘None of that was real, was it? About Peg Powler?’

‘What do you think?’

I shrugged.

‘It was real,’ Una said. ‘How old was she?’

‘I couldn’t say,’ Nana said. ‘Old and young at the same time. It was queer.’

‘What was she wearing?’

‘I only saw her up to her chest, but it didn’t look like she was wearing anything.’

Una clenched her fists. ‘What do you think would’ve happened if she’d got you?’

‘Una, lass, I don’t know…’

Una turned to me. ‘Don’t you believe her?’

‘I dunno…’

Nana wriggled her right foot. ‘Slipper.’

Una pulled it off.

‘Sock.’

Una gripped the toe of the sock and tugged it off inch by inch, revealing Nana’s thin, splotchy shin. We gasped: there, just above the nub of her ankle, was a sickle of scar-tissue.

So I think that’s the Green Girl in the painting, Stephan. Her name is Peg Powler and she quickly became more than just another spooky tale to Una. She kept pestering Nana to retell the story, demanding more information each time, and I think Nana was puzzled by her growing obsession. Worried, even.

One day not long after, Una didn’t come to school, or appear round my house for tea the way she did most days. When she finally turned up in my backyard the next morning, her clothes were stiff with mud and she had sticky-jacks in her hair. She’d walked all the way to Egglescliffe, to where Nana had played hide and seek, and waited on the riverbank all night for Peg to come. She’d even splashed her feet in the water. I asked Una what she’d seen, and anyone in it simply to get swept up in some girlish nonsense would’ve gone, ‘I saw her! I saw!’ But Una just shook her head, ground filthy fists into her eyes.

*

I’m not sure I want to see this painting of Peg you tell me Una did. There’s always been a cranny of my mind where that witch has festered (I never told Alan about her when he was a boy because I didn’t want him carrying her around like I’ve carried her). I also worry that confronting Peg again would somehow unleash her…or more specifically, unleash the way I felt back then. It’s ridiculous, but as Peg tightened her grip on Una’s mind, I felt left out once more. Jealous even, because I wondered if Una, my only friend, heard Peg the same way Nana had done on the riverbank that day: a voice calling from a place I would never be brave enough to follow.

Jean.

4/5/1991

Dear Stephan

My folks visited today, and it’s the same old rigmarole each time Dad and Vincent get together. Nodding at each other like they’re suffering whiplash.

Grunt: ‘Vincent.’

Grunt: ‘Ronnie.’

Men!

Today, after the usual warm salutations, Vincent had the good sense to make himself scarce and go over to his garage, or the Labour Club, or his allotment. Or wherever he really goes when he says he’s going to those places. Once he was gone, Alan emerged from his room and made the tea. He gets on well with his Gran and Granddad, and I can’t tell you how happy it makes me. Dad asks him the time-honoured question of whether he’s courting. It makes the lad squirm, bless. I’d love it if Alan was courting, but he isn’t. I know.

As always, Mam took me in, searching for signs of weight loss, bags under my eyes, new things of pills on the side. Her Avon foundation was the colour of a peach melba, and when she plonked herself down on my bedside chair, the cushions whoomphed exactly like the chip pan had when it went up last year and I, like a divvy, went to throw water on it. Vincent grabbed my arm at the last second, spinning me into the counter and bruising my hipbone, which lead to the X-rays that found the shadows on my ovaries. Lucky, really. Not that I could tell folk round here. When they saw me on my crutch, I knew what they really thought had gone on.

But that’s all by-the-by. Mam told me about the family recently moved onto 1 Loom Street, Una’s old house. More 2am slanging matches, more thudding ‘techno’ music. The parents looked barely out of school themselves, Mam said, yet had three bairns. I told her to look on the bright side. If they were anything like the last family, they’d be gone within the year.

‘But pet,’ she replied, ‘what if the next lot’s worse? At least these ones wear shirts most of the time.’

The estate is going to the dogs. Private landlords who’ve never once set foot in the place are snapping up the ex-council properties to rent back to the self-same council for silly money when they don’t have enough homes to house the homeless. It’s madness. Or they fill them with all kinds of trouble makers. Those who can are upping sticks. But not us. Vincent bought our house ten years ago, and he’ll refuse to move no matter how bad it gets. And bad it’s getting. There’s less and less familiar faces around these days, and packs of kids roaming the streets. They hang around bus stops and corners until all hours. When I see them, I wonder: Where are your parents?

But then I think of George and Talitha, and I know.

To the north of the estate there is a patch of woodland through which the Cong Burn used to run, a little river which eventually fed into the Tees (well, I say river, but really it was more of a stream, and it’s dried up now, or so I’ve heard. They blocked it to build the new houses somewhere between here and Yarm). On the bank of the burn was a large pipe above the water: an entrance to the underground labyrinth of old sewers connected to the derelict waterworks on the other side of the estate.

Mam had drummed it into me: STAY AWAY FROM THE BURN PIPE.

And, being a good girl, I always had. But then Una got her idea.

It was autumn and we must have been knocking on thirteen. The falling leaves were the red / gold of Mam’s special New Year tablecloth and crunched like pork scratchings under our feet. I whined the whole way: ‘We don’t even know where it comes out.’

‘Exactly,’ Una said, clicking her torch on and off.

‘But what if it doesn’t come out anywhere?’

‘What if it comes out in another world?’

‘There’ll be rats.’

‘Rats schmats.’

We arrived at the bank opposite the pipe. The burn flowed on, towards the Tees, further than I had ever been. Without taking her shoes and socks off, Una sloshed into the water up to her bruised shins.

‘Una, I don’t want to…’

She pulled the spool of twine out of her knickers. ‘It’s like that minotaur story from school. We won’t get lost.’

‘We should go back.’

‘Haway, Jean. Don’t be a wimp.’

‘I’m not being a wimp.’

She hoofed up a wing of water. ‘We’re always saying how boring everything round here is. Well this is adventure.’

‘But I’ve got my new clothes on.’ Which was true. A peach-coloured blouse and cotton skirt from Woolies.

Una’s eyes narrowed to knife nicks. ‘I’m going in with or without you.’

‘Una, please.’

She tossed the spool into the pipe and clambered up after it.

‘Please.’ I had tears in my eyes.

She tied one end of the twine to a bolt on the pipe’s rim and tugged it to make sure it held. The pipe sighed around her. Stooping, she shone the torch down its throat, wolf-howling – Awoooooo – after it. Her face was all twisted when she looked back at me.

‘Last chance,’ she said.

‘Una…’ I said uselessly.

‘Tell them I died a hero’s death,’ she said, and melted into the darkness.

I was frantic. I paced and blubbered along the bank. Once, twice, three times I took off my shoes and socks and tippy-toed into the freezing water, only to once, twice, three times turn back. I thought about running home and telling Mam, but I’d already been warned about being here. Plus, there was the unspoken rule every child knows – you NEVER told. Still, what if Una got lost? Became nothing but bones and a ghost story herself? I felt pulled in so many directions that the only thing for it was to sit on the bank and wait.

Una was right. I was a wimp.

Time passed. The light faded and cold crept on. To stave off panic, I started setting meaningless deadlines: ‘One more minute and I’m leaving! One elephant, two elephant, three elephant…’ But after sixty elephants had trooped past trunk-to-tail, I didn’t budge. Then: ‘Right, when that tree-shadow gets to that rock, I’m off!’ Watching it inch towards its destination was torture because I knew I wasn’t going anywhere once it did. I tried getting angry – this was all Una’s fault! She had no right! But the gathering darkness chose to throw its weight behind Fear, not Rage, and my hissy fit quickly fizzled.

Finally, unable to hack it any longer, I got up to leave. I was just brushing the muck off when I heard a noise from deep within the pipe.

‘Una?’ I said, as loudly as I dared.

No answer. The noise got louder. What sounded like footsteps. Clanging footsteps getting closer.

‘Una is that you?’

Clang…clang…clang…

‘This isn’t funny…’

Clang…clang…clang…

‘Una, I’m leaving you!’

The string Una had tied to the bolt snapped and disappeared down the pipe like sucked spaghetti. It was sprinting now – Clang! Clang! Clang! – and just like Nana, my legs wouldn’t work – CLANG! CLANG! CLANG! – The pipe opened wider, ready to swallow me, and a hideous voice wailed:

JJJJJJEEEEEAAANNNNNN!

I stumbled, tumbled into snarls of brambles, screaming.

Una’s pale, laughing face appeared at the mouth of the pipe. ‘Did you think it was Peg Powler come to get you?’ She sploshed into the burn and waded up the bank to where I lay struggling in the thorns. I kicked at her hand when she held it out for me.

‘Jean, I was just joking.’

With smears of scum under each eye, Una watched me struggle free. My whole body felt slashed. Blood from my cut wrist stained my blouse, which was torn and twisted around me. I got shakily to my feet.

‘God,’ Una said, ‘it was just a joke.’

‘I hate you,’ I said.

‘I didn’t mean to scare you.’

‘I wasn’t scared!’

She almost managed to supress her smile. Almost.

I stormed off through the dead leaf drifts before she could see me cry, my name following me through the trees as I did.

Oh, did I catch it when I got home! As punishment, I had to spend the whole half-term clearing out the cellar for the rag-and-bone man. Hauling stacks of mouldy old Gazettes and scuzzy lino offcuts in damp boxes that came apart in my hands. There were spiders, too. Big ones. But I never told on Una because, really, who was there to tell? She wasn’t Mam’s daughter. As young as I was, I still grasped the fact that getting my mother involved would have only rocked the uneasy reality of my family’s relationship with hers. Una was allowed to keep me company while I worked, and she took care of the spiders for me because she felt bad. In the shadows of the cellar’s single bare bulb, I was bedraggled and gaunt-looking. We looked like twins down there, I thought, me and Una. But only down there. That distinction being the real difference between us.

Now that I’m a mother, I look back differently on that day at the pipe. I wasn’t a wimp. On the contrary, the reason I didn’t follow Una was not because I was afraid of life, but because I valued life. It was Una who had no regard for it, because precious few people had ever had regard for her.

In your letter, you told me that the trail on Una had gone cold – ‘dead’ was the word I think you used – so it’s impossible to know if she ever had children of her own. This may sound harsh, but I hope she never did. In a way, the Cruickshanks were a lot like this estate falling to pieces around me now. Just not up to supporting multiple generations.

Tired now. More soon.

Jean.

17/5/1991

Dear Stephan,

What did you want to be when you grew up? Not what you became, I imagine. How many bairns dream of becoming art dealers? In my day, boys aspired to be train drivers and girls wanted to get married, or be air hostesses. Personally, my own future was always clouded, though I did do well enough at school to pass my 11+ and get into Thornaby Grammar. This was a real source of pride for my parents, as it was unusual for someone from my background to do that (my sister Agnes hadn’t, much to my satisfaction). It also meant I no longer had to go to school with the likes of Elsie Stanger and my other bullies. I met new girls, started making friends.

Una bombed the 11+ and ended up at the secondary modern on the outskirts of the estate, ‘Scunner Academy’ as my Thornaby friends called it. Not that Una cared. You could have put her on the moon and she would have kept painting those riverbanks. She was focused in a way I would never be. For instance, I used to write. Just silly little stories and poems that I never showed anyone, and which I stopped once I got a bit older and boys came along. Maybe I shouldn’t have done that, but giving up was easy because I didn’t have the fire the way Una did.

In this respect, Alan is like me. He drifts. Vincent is always on at him to get a job, get a trade, and I try telling him our son just isn’t cut out for that kind of thing. Besides, it’s 1991. What ‘trade’ is there? Since I was a lass, the forges have been privatised, consolidated, chopped up, sold off. Why make steel here if it’s cheaper to ship from China? Everybody is being made redundant – tens of thousands of people. Whole communities. Ironopolis is falling.

Even so, Vincent says: ‘There’s always work for a man what can use his hands.’ (Vincent’s hands are as hard as gravestones. I suspect he likes having parts of himself he can’t feel.) He accuses me of mollycoddling our son. And maybe that’s true, but I have my reasons.

It isn’t motherly bias when I say Alan is one of the brightest people I’ve ever met. It’s just that formal education never sat right with him. When he was fifteen, he had an accident and missed a lot of school. He tried catching up, but it would have been beyond anyone. He did badly in his CSEs, and the NVQs I encouraged him to do afterwards weren’t a good fit either, so now he’s in limbo like most folk around here. He did recently manage to get a part time job at the library in town, which at least gets him out of the house a few hours a week, but I still worry he’ll shrivel up and lose his natural curiosity. I dread he forgets there are other ways to view the world, so thinks the world around him is the only one there is.

So I do my part to keep him engaged. For example, I have him bring home books from the library for him to read to me. Unfortunately for him, I have something of a weakness for the Danielle Steeles’ and Jackie Collins’ and, yes, the Mills and Boons’ of this world, so we alternate those with books of his choosing. Alan hoovers up everything: astronomy, science, history, someone called Neecha (is that the spelling?). I’m not ashamed to admit most of it sends me cross-eyed. At the minute, we’re learning about bridges. Did you know that in 1885, a woman threw herself off the Clifton Suspension Bridge (245ft) because she’d had a fight with her boyfriend, only for her big floaty Victorian dress and frilly underthings to slow her fall enough for her to survive? Tell me Stephan, does that count as being unlucky in love?

What am I on about? I’m trying to tell you about the library van.

Me and Una were bookworms, but while she liked reading about trapped riveters, I preferred more traditional stories. Enid Blyton was my thing: ‘The Famous Five,’ ‘The Wishing Chair,’ ‘Naughty Amelia Jane,’ and ‘Mr Twiddle.’ My favourite was ‘The Magic Faraway Tree,’ because of the helter-skelter down the centre of the trunk. Mam would climb into bed with me and read until I dropped off. Later, when I got older, I began reading along with her, until soon enough I was tearing through book after book on my own. By the time I got into my teens, I’d moved onto more ‘mature’ stories like the Marcy Rhodes series, which all my Thornaby friends were reading. They were full of squeaky-clean blondies, torn between two college-bound buzzcut boys – the Quarterback (whatever that was) or the Debate Team Champ (ditto) – as the Big Dance loomed. It was an alien American world that jarred with the one I knew, with the coal scuttles and cups of Bovril with cream crackers crumbled in. The way the back boiler never caught on mornings so nithering the first thing you saw when you opened your eyes was your own breath clouding above you. There were also books in Thornaby Grammar’s library with titles like ‘Air Hostess Ann,’ and ‘Emily in Electronics’: about young lasses heading out into the World of Work. Usually they ended up leaving their male colleagues in the dust, doing so well that the boss’ reward was to marry them and give them a big house full of bairns to look after. Daft, but we just accepted that kind of thing back then.

Every second Wednesday, the mobile library would come down Loom street, and I looked forward to that for two reasons. One, I wanted grown up books, and two, the man who drove that van. Henry. My first real crush.

If Teddy Boys had long since been out of style come the early 1960s, nobody had seen fit to tell Henry. He still booted around in his drape coat and brothel creepers, his hair pomaded into sleek liquorice. Swallow tattoos on his hands where his thumbs and index fingers met. Proper Geordie and proud, he said. Had grown up on Arthur’s Hill, a stone’s throw from St. James’ Park. My name in his mouth did something to me that I still then didn’t fully understand. He could make that ‘ee’ go on forever: Jeeeean…

I couldn’t loan silly little girl books from Henry, so one second-Wednesday I put on my best skirt and sneaked a dab of Mam’s perfume. I hung at the back of the van, browsing the shelves while Henry served the bairns. He was so good with children. Back then, remember, it was the era of speak-when-you’re-spoken-to, of watch-your-Ps-and-Qs, but Henry let them say whatever they wanted. He crouched down to their level, looked them right in the eye, and didn’t flinch from their sticky little hands. I didn’t know why his being good like that was attractive to me, but it was.

Once most of the bairns were gone, I picked out the thickest book I could find and plonked it down for him to stamp.

He read the title. ‘Finnegan’s Wake. Its canny big, like.’

My thing at the time was Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which me and my Thornaby friends had seen five thousand times at the Ritzy. I fixed him with the coquettish pout I’d perfected in the mirror, and in my best Audrey, said, ‘I suppose you think I’m very brazen or tres fou or something?’

A blank look. I was mortified. He stamped the front page and handed the book back to me. Our transaction was complete.

Desperate to keep talking, I said, ‘Have you read it?’

‘I’m not a reader.’

‘But you drive a library…’

He shrugged.

Someone else was behind me. Henry’s eyes moved over my shoulder and I was forgotten.

Oh Jean! Stupid, stupid Jean! I scurried away with my book, on the lookout for the nearest hole to crawl into, but just as I was leaving I heard Henry say, ‘I know this one! I saw a film of this.’ I looked back.

Henry was turning the copy of ‘Frankenstein’ over in his hands. He said, ‘They stuck a hunchback’s brain in his body and he smashed up this posh dinner party.’

‘I don’t like films,’ Una said, popping her elbow.

He looked at her strangely, a slow smile spreading. ‘Who doesn’t like films?’

‘I don’t want their pictures in my head.’

‘You’re a serious one, aren’t you?’ He stamped the book and held it out to her, but when she took it he didn’t let go.

‘And you,’ Una said, ‘are you serious?’ Her voice was low and fluid in a way that unsettled me. Her eyes on his, the book trembling between them.

‘Where it counts,’ he said, letting go.

Neither of them seemed to be aware of my presence. I felt like a Peeping Tom, a creep.

‘Tell me how it ends, eh?’ he said.

I left the van and stalked home, my fingernails digging into the cover of my ridiculous book. What had just happened? Here was the one area I felt sure I had the better of Una, and yet everything I thought I knew about boys had somehow just been brushed aside by her flinty weirdness. She didn’t even have a chest!

Which is, Stephan, all to say that I was out of my mind with jealousy.

I have to go. Alan’s bringing the tea up now. Tonight, we’re tackling some of the new Judith Krantz (Alan’s birthday gift to me – I turned 45 a couple of weeks ago. Vincent got me the black dress from Selfridges I’ve had my eye on). Krantz-wise, I’ll bring you up to speed: Eve was all set to become an opera singer before she defied her family and ran off with a music-hall crooner. But then he got pneumonia, and Eve was a smash when she started singing to pay the bills. Now this posh lad Paul de Lancel is sniffing about Eve. Not sure what his snooty family will make of it when he inevitably makes his move…

There’s been a few racy bits. Alan gets a little flustered in places, bless him.

As always,

Jean.

1/6/1991

Dear Stephan,

When we were about fourteen, Una’s mother Talitha hit a rough patch and never quite recovered, although that we realised only in retrospect. Una had already told me what little she knew about her mother. When Talitha was about the same age we were then, she, along with her five brothers and sisters, were preparing to escape Poland to some distant Teesside relative, just as their country became a bloodbath. I’ve had Alan read me the history. In September 1939, the German armies advanced from the west, bombing and burning and slaughtering at random. Terrified Polish civilians fled east, only to run smack into the Red Army, who had signed a pact of non-aggression with the Nazis. Millions were lost: men, women, and children were massacred, raped, or worked to death in Siberian gulags. Twenty thousand souls per mass grave. Over three million Polish Jews alone erased in the Final Solution.

But what the books don’t explain is how Talitha, a teenage girl who had previously never left her home town, could be swallowed up by such atrocity only to reappear on British shores three years later, clutching in a hand that was missing a ring finger a scrap of paper with her second-cousin’s address on it. Those three years – where had she been? How had she survived where millions perished? What had happened to her parents? Her brothers and sisters? It was a mystery not even Una knew. Then, three months after her arrival on Teesside, the now eighteen-year-old Talitha met and married George Cruickshank, a young private. She fell pregnant just before he was shipped to Sicily, where he lasted less than six months. When George came back he wasn’t, as they say, the same.

Those were the facts as I knew them, but facts, as you know, aren’t everything.

The last time I talked to Talitha was in the summer holidays a year after I’d started Thornaby, which would make it 1961. I wasn’t seeing as much of Una by then, and my accumulated guilt eventually drove me to knock on her door one morning to see if she was in. Talitha answered, which was exactly what I hoped wouldn’t happen.

The kitchen reeked. From the ceiling hung flypapers so loaded with bluebottles that they sagged like rank party streamers. Lino filthy. Sink clogged with dirty crockery. I declined tea, but she started making it anyway. Her loose-fitting dressing gown was Chinese in style, stitched all over with their funny writing. It kept falling open to reveal a stained chemise through which her large, dark nipples showed.

Kids always say the same laced-up things to their friend’s parents, and I was no exception: ‘How’s Mr Cruickshank, Mrs Cruickshank?’

And any other friend’s parent would have given a laced-up response, but this was Talitha: ‘Oh, don’t get me started on him. Laziest creature in all of Christendom, him. Promised me we’d live in a palace – sit, sit, sit – but is this a palace?’ – she crouched to look in a cupboard for clean cups – ‘This concrete coffin? This cement maze? People’s googly eyes oogling through my windows, the nosey parkers!’

Was that directed at me? I liked a good look through a window.

Talitha put cups on the table. ‘And that’s not all,’ she said. ‘I see things.’

‘What things, Mrs Cruickshank?’

She planted fists on the dirty tablecloth. The sleeves of her gown rose to reveal scarecrow arms laced with powder-blue veins. Stark black hairs against blanched skin.

‘The dead,’ she said.

‘Is Una upstairs, Mrs Cruickshank?’

‘The dead are everywhere round here,’ she said. ‘Trapped. Buried. Do you ever feel like that?’

‘Like…what, Mrs Cruickshank?’

‘Like we’re all piled on top of each other? One mass grave?’

I was fourteen. What could I say?

Talitha shooed a fly from the sugar bowl. ‘But all that idiot