7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

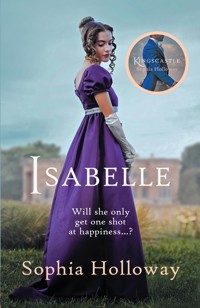

From the author of Kingscastle and The Season... Isabelle Wareham, whilst caring for her beloved widowed father, has not seen much of the world. After his death, Isabelle finds she is no longer her own mistress but under the guardianship of her unscrupulous brother-in-law, Lord Dunsfold, who sees her as a way to improve his own fortunes. The outlook is bleak until events throw Isabelle and the impoverished former soldier Lord Idsworth together. However, Dunsfold is determined to force her into a more lucrative match and Isabelle will need to rise above her circumstances to grasp her chance of happiness.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 415

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

ISABELLE

SOPHIA HOLLOWAY

For K. M. L. B. and in memory of K A H

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

The taller of the young women clad in black paced the room impatiently. She had deep chestnut hair that was actually shown to advantage by the sombre silk, and she carried herself imperiously. Her features were good, and only upon a second glance would it be noticed that she had a sharp nose, and that her green eyes were agate hard.

The aged butler entered and spoke to the other lady, who was seated before the fireplace and gazing into the flames. She was a more muted version of her sister, with nut brown hair, gentle features and eyes that mixed green and hazel to the point where it was impossible to describe them in simple terms.

‘The gentlemen will be joining you shortly, Miss Isabelle. I believe the sad business is concluded.’

‘Thank you, Wellow. I think some tea would be in order.’

‘Yes, Miss Isabelle.’

He bowed slowly, more from infirmity than deference, and withdrew. The taller lady snorted.

‘Wellow ought to have been retired years ago. He is so slow, and has a vastly inflated idea of his own importance in this house. No doubt he was listening where he had no right to be. He will be one of the first things that I get rid of, along with the awful wallpaper in the morning room. I am sure that the background was white and not cream in my mother’s day.’

Isabelle Wareham winced. Cornelia always referred to the late Mrs Wareham as ‘my mother’ as if she were hers alone. Cornelia was nine years old when Isabelle was born, and the joy at her safe arrival after several unsuccessful pregnancies had been turned to grief when Patience Wareham had died within twenty-four hours of the delivery. Colonel Wareham had always seen his younger daughter as his dear wife’s parting gift, but Cornelia was convinced that Isabelle had killed her mother, and had resented her from birth.

‘And,’ added Cornelia, pointedly, ‘I cannot conceive why Papa did not have the dining room improved.’ She cast her sister a look which clearly intimated that she blamed her for this omission on his part.

‘I hardly think this the time to consider such—’ Isabelle’s soft voice, surprisingly deep but melodious, was interrupted by her elder sister.

‘And it is impertinent of you to tell me what is or is not suitable. You think I do not grieve? Well, I do, but for poor Papa being left as he was these last years, incapacitated, dependent. This was a release. I will remember him as he was, vital, active and happy.’

She did not actually say ‘remember him as long ago when you were not here’, but she might as well have done so.

Isabelle coloured. Normally a heated exchange would have ensued, but she was too tired, too weary with grief and the responsibilities that her father’s death had laid upon her.

In a way Cornelia was right; it was a release. Colonel Wareham had been an active man on his estate and in the local community. The seizure, some four years past, which had left him virtually chair-bound, barely able to stand long enough to be assisted down the stairs, and both slow and slurred of speech, had imprisoned his body, but not his mind. So much had to be done for him, by her, and by his faithful valet, Sileby, but he had never complained, and even said it had been the opportunity to enjoy the things his quicker pace of life had overlooked. He had watched the birds in the garden outside his library, painstakingly taught Isabelle, thrust into running the house at the age of fifteen, and being involved in management of the estate, how to deal with such things. They were not the years he had anticipated, but he had used them well, and they had not been miserable. Cornelia did not understand. Married these ten years past, running her own household and nursery, she saw only the outward limitations of her father’s state. Nor did she appreciate what it had meant to Isabelle. When she had reached fifteen, Cornelia had gone to her aunt, Lady Colebatch, Mrs Wareham’s sister, and spent two years being prepared for Society. Lady Colebatch had brought her out, approved Lord Dunsfold as a match, and smiled benignly upon her success.

Isabelle had, at a similar age, neither wanted, nor indeed been able, to leave her Papa, and Lady Colebatch had succumbed to influenza the following winter. Cornelia had never even mentioned bringing her sister out herself, in part knowing she was needed at home. If she contemplated any future for Isabelle, it was as the wife of some local squire, probably Edwin Semington, who was Colonel Wareham’s godson, and who was, in her opinion, a solid, reliable man of sense who would keep the far-too-independent Isabelle under suitable restraint.

The door opened, and three gentlemen entered, the first obviously in an agitated state, the second thoughtful, and the third slightly amused. Cornelia Dunsfold raised an eyebrow as she looked at her husband.

‘Well?’

‘It is preposterous.’ Lord Dunsfold’s naturally florid complexion had assumed an even more crimson hue. ‘I said so to Filey, but he says it is all in order and cannot be faulted.’

‘For goodness’ sake, my lord, just tell me what the Will contained.’

‘He left it all to her,’ he declared angrily, pointing at Isabelle.

‘All of it to my sister?’ his wife blinked incredulously. ‘But I am the elder.’

‘In such cases as this, Lady Dunsfold, where there is no title or entailments, the disposition of the estate is entirely up to the testator, so Filey informs us,’ explained Mr Semington, shaking his head, ‘and it is not everything, exactly.’

‘You call the property in Leicestershire worth having? And a portion of the investments in Funds? When this,’ Dunsfold threw his arm out, expansively, ‘comes to Isabelle?’

‘Jolly good thing it does, I say.’ The amused gentleman smiled at Isabelle, whom everyone else was talking about but not to, and then looked challengingly at Dunsfold. ‘Cornelia is taken care of, established. Isabelle has spent her life here and cared for Uncle George in his ailing years. This gives her security and, dash it, she deserves it too.’

‘You are a fool, Charles, so I will not deign to respond to that remark,’ Lady Dunsfold snapped at her cousin.

Isabelle cast him a grateful look. Sir Charles Wareham, son of Colonel Wareham’s elder brother, was not, perhaps, of the highest intellect, but he was sweet-natured and pragmatic. Although nine years her senior, the gap in age seemed very small, for circumstance had made her mature quickly, and he retained a youthful simplicity of attitude. He had attended his uncle’s obsequies with genuine sadness as a nephew, as well as in his role as head of the family. He had been at the reading of the Will in that capacity, without any thought of being named, and had been rather touched that his uncle had left him his favourite shooting piece. He only wished that he had been left in partnership with Lord Dunsfold as Isabelle’s guardian, until she came of age in nearly eighteen months’ time. He had however, been named as joint trustee of the estate until that time. It would undoubtedly be onerous, because Dunsfold was a man he both distrusted and disliked intensely, since Dunsfold openly treated him as a buffoon.

The antipathy was mutual. Dunsfold might be a viscount, not, as he phrased it ‘a mere country baronet’, but Sir Charles’ forebears had held both land and title since before the Wars of the Roses and the Dunsfold elevation dated only as far back as the Restoration. The viscount, if pressed, would murmur about ‘services to the Crown’, but he was not the only one to know that these ‘services’ had been to renounce any interest in a mistress upon whom the royal eye had fallen. It rankled with him, nearly as much as the fact that the Wareham estates, cared for and managed over generations by men who did not aspire to cut a dash in society, were extensive and profitable, whereas he had been forced to dispose of assets to cover his father’s debts. He had anticipated his wife, and thus himself, inheriting Bradings, with both pleasure and some relief. Certain investments which he had been persuaded to make of late had proved disappointing and the sale of the property would boost his depleted coffers.

‘It was always expected that Bradings would come to me.’ Cornelia Dunsfold sounded petulant.

‘Expected by you, yes, but it makes no sense otherwise. It is the best way to ensure Isabelle’s secure future. Was Dunsfold living off the expectation? The more fool him.’

‘Lady Dunsfold has a point, surely,’ interposed Mr Semington, hurriedly. ‘The eldest, or in this case the elder, child normally inherits the main property.’

Sir Charles cast him a look of dislike.

‘You really are a prosy bore, Semington. Godson or not, I am not surprised Uncle George left you nothing but a case of port and his butterfly collection. Dust collection, I call it. You were the only person ever to wax lyrical over those pinned moths.’

‘You are not a lepidopterist,’ remarked Semington, condescendingly.

‘I should dashed well say I am not a leopard-anything. And Uncle George never looked at those cases any time these last twenty years.’

‘We stray from the point,’ announced Lord Dunsfold, loudly. ‘The thing is that my father-in-law left Bradings and the entire estate to Isabelle. However, she is under age and so he appointed me as her guardian until that date. I admit that I think that putting the estate in trust and preventing me making any decisions concerning any disposal of assets without recourse to,’ he paused, and looked disdainfully at Sir Charles, “the Head of the Family”, totally unnecessary, but …’

‘He named me as the other trustee just so that you were not given free rein to tamper with the estate, that’s why.’ Sir Charles grinned, but his eyes flashed. There were limits to how far he would put up with being insulted. He looked to Isabelle, who was frowning, and his look softened. ‘Don’t you worry yourself, Isabelle. You will not find yourself without a feather to fly with when you come of age.’

‘I am not worried, dear Charlie, but,’ she looked at the others, ‘I object to being discussed as though I were an inanimate object when I am sitting here before you all. I did not know of the guardianship, though I should have thought about it, but Papa did tell me that I would not need to worry about the future because he would provide for me.’

‘And you said nothing to me?’ Cornelia glared at her sister.

‘I am not sure that you ever listen to a word I say, Cornelia,’ she snapped suddenly, and drew her hand across her eyes, ‘so why should I waste my breath?’

She got up, agitatedly, and went to the window. The branches of the beeches showed nearly bare in the October sunlight, and she watched a gust of wind toss a heap of bronzed leaves nonchalantly into the air and drop them as suddenly. Life was just as it always was and yet was so different. The tossing of leaves by the wind was an inconsequential thing but one to which she would have drawn her father’s attention, and now he was not there. A huge void had appeared in her life and gazing into it brought a lump to her throat and tears to her eyes. She swallowed hard and blinked.

‘You are overwrought, Isabelle,’ murmured Mr Semington and came to pat her hand, patronisingly, and a little possessively. She pulled it away, colouring.

‘Not overwrought, Edwin, just grieving. You seem to have forgotten that in your interest into what Papa left in his Last Will and Testament, even before the earth has settled over him. And I do wish you would desist from acting as if you were my brother.’ She turned her face away.

‘Now, my dear, you know full well that the last way in which I would think of myself would be as your brother,’ he responded, smiling in a way which made her long to hit him. He had taken it into his head that she would marry him, and nothing that she might say or do seemed likely to disabuse him of this belief. That she did not care for him did not seem to worry him in the least.

Wellow entered the room before the atmosphere could become even more fraught, followed by the family solicitor, whom Isabelle had ensured would be invited to partake of tea. As Wellow remarked later to the housekeeper, Mrs Frampton, it was clear to see that it was not a scene of family amity.

‘Her ladyship looked as if she had been sucking a lemon, and his lordship was choleric. Well and truly out of joint, their noses are, to be sure. I just hope as they do not make life hard for poor Miss Isabelle, though.’

Filey, the family solicitor, was more concerned that life would become hard for him, mediating between Sir Charles and Lord Dunsfold. He knew of their animosity and would guarantee that whatever one suggested the other would try and veto. He might think not giving Lord Dunsfold sole control of the estate a sensible action by his late and respected client, but he also thought he was in for a testing eighteen months. The angry looks that the two men exchanged were merely a visual indication. It was enough to bring on one of his headaches.

Cornelia glanced briefly at the man of law and sniffed. Isabelle turned and smiled a little wanly at him.

‘Do take a seat and some tea before your departure, Mr Filey. I know you have quite a drive ahead of you, back to Malmesbury, and the wind is bitterly cold.’

He gave her a hint of a smile and bowed in acknowledgement. Miss Isabelle always treated him with courtesy, not as some insignificant minion. It was a pity in some ways that her years did not match her experience, for in all honesty, she could have taken up the formal control of the estate without recourse to any but himself on rare occasion, having had to deal with most of the business aspects of it during the last two years or so. She looked more than nineteen, for certain. She might not have had a London Season, but she had poise and a certain natural gravitas which cloaked her youth.

The presence of the lawyer effectively stifled any further mutual recriminations between Lord Dunsfold and Sir Charles, and Isabelle was grateful for it. Only when Filey rose and announced he had best depart before the light began to fail, did Lord Dunsfold do more than engage in a muttered conversation with his wife.

‘We have decided, Cornelia and I, that it would be best for you to return to Lincombe with us. The house can be shut up for the winter, and—’

‘Why on earth should I leave Bradings?’ Isabelle was stunned.

‘You are too young to live here alone, without someone to guide you. Heaven knows how badly you will be cheated by tradesmen and your tenants,’ her brother-in-law declared.

‘They never did so before, and I have had to deal with them increasingly as Papa grew more infirm.’

‘Ah, but he was still there, behind you, so to speak. Now you are quite alone.’

‘Thank you for reminding me of that,’ she flashed.

‘So little respect!’ Cornelia shook her head. ‘If that is how you have been allowed to go on, I despair of getting you a husband, Isabelle. A want of conduct in a girl is most certain to put off suitors.’

Edwin Semington coughed, pointedly, as if to assert that however true this might be, he was prepared to overlook the fault.

‘Since I am in deep mourning that is totally irrelevant, Sister. And besides, I am not so sure I want any husband, least of all one of your choosing.’

Lady Dunsfold was speechless, as much from surprise as outrage.

‘If Isabelle wants to remain here, why should she not do so?’ Sir Charles had kept silent, but now joined the conversation. ‘Since she is in deep mourning she won’t be going into society anyway, and I am close enough to trot over every so often and make sure all is well.’

Husband and wife exchanged glances.

‘I wish to remain here, in my home,’ declared Isabelle. ‘I will not be lonely here, for there is Wellow and also Mrs Frampton, and—’

‘Servants! Oh Isabelle, if that is what you consider company, you are a lost cause.’ Cornelia pulled a face and sighed in a theatrical manner. ‘You mark my words, by the spring you will be begging us to take you in when we go to Bath.’

Isabelle said nothing for a minute. Her head was beginning to ache, and all she really wanted to do was go to her bedchamber and give in to the rising ball of grief in her chest. Now it seemed she was not even to be permitted to remain in her beloved home.

‘Please, Cornelia, I beg of you. Let me stay here where I have occupation. At Lincombe I would simply be in the way and have nothing to do.’

Truth to tell, Lady Dunsfold, having at first thought her lord’s idea very wise, was beginning to regret their generosity. She had forgotten just how embarrassingly forthright Isabelle could be, and how she would have to make excuses for her behaviour. Her friends might applaud her charity, but soon enough they would be shaking their heads over her inability to school her younger sister into decorum. This gave her the chance to back off without appearing to withdraw the offer.

‘If you are so set on it, Isabelle, I suppose we might permit it, whilst, as you say, you are bound to be out of society.’

That she would also have her social life curtailed had given Cornelia more tears than her father’s demise, but as a married woman with a wide circle of friends who might still visit even if she might not organise any large-scale social events, there was no likelihood of her being immured in Lincombe. The same would not be true for Isabelle at Bradings. More fool the girl.

An uncomfortable silence descended upon the room as the daylight became gloaming. Sir Charles had but three miles to travel home to the Hall, and delayed as long as he might, thinking how little he liked to leave Isabelle with the Dunsfolds and Semington. In fact, he could not see why Semington had remained at all, since he might as easily return to his waiting mother, almost the same distance away but in the opposite direction. He came up with the happy idea that since he could not remain all evening, he would at least get Semington to withdraw. He did this by the simple expedient of rising and saying to Semington, ‘Time you and I were off home. Your mama will want you home before it is full dark, or else she will fret, eh?’

Edwin Semington had little wish to leave but this statement was very true. He sighed, and agreed, with due reluctance. He bade Lord and Lady Dunsfold a very polite farewell and took Isabelle’s hand in what he thought of as a sustaining grasp as he wished her goodbye.

‘You know where I am, whenever you have need of guidance.’

This annoyed not only Isabelle but the other gentlemen present, uniting Sir Charles and Dunsfold for a brief moment.

‘She has relations to guide her, Semington,’ growled Sir Charles.

‘Presumption!’ snorted Lord Dunsfold.

Mr Semington coloured and gabbled his farewell.

‘He merely let his compassion get the better of him,’ murmured Cornelia placatingly, as the door closed behind him and Sir Charles.

‘He acts as if he had a right. I hate it, hate him,’ Isabelle spluttered.

‘That shows that you are equally unrestrained, Isabelle.’ Her sister looked down her nose at her. ‘It is to be hoped that you will strive to curb such intemperance.’

Isabelle flung her a look of intense dislike and, to show what she thought of this statement, flounced from the room, slamming the door behind her. The Dunsfolds looked at one another, in mutual and silent agreement. Their point was proven, as far as they were concerned.

CHAPTER TWO

The autumnal weather conspired with Isabelle’s grief. For the best part of a fortnight it rained, if not continuously, then so frequently as to render even a gentle hack about the countryside liable to result in returning soaked to the skin. She was listless and inclined to think only of the past. In the immediate aftermath of her father’s death there had been practicalities with which she had dealt, aided by Filey, and with the moral support of Cousin Charles. Only when her sister and Dunsfold had arrived and taken over as if they owned the house had she had empty hours in which to contemplate her loss, and now everything was in hand and only the empty hours seemed to remain. She wandered about the house, a black, silent shadow, gravitating always towards the library, where she had used to sit with her father, and where the comforting smell of ageing leather bindings seemed to mix with an echo of his presence. There she sat and watched the rivulets of water course down the windowpanes, nature’s tears reflecting her own and distorting her view of the world without. The initial visits of consolation had been replaced by a reluctance to ‘disturb’ her, and though she had resented having to keep her poise and listen to well-meaning, though perfectly sincere, condolences and reminiscences which made her feel her loss more acutely still, seeing nobody now felt worse.

She was also contemplating the unfortunate truth that there was no requirement for Sileby, since he had nobody to valet, though he was so much more than her father’s personal servant. When Isabelle was born there had been a wet nurse, and a nursemaid, but the first had of course departed before Isabelle could remember her, and the maid had left to marry when Isabelle was four. The governess, as Cornelia frequently informed her little sister, ‘belonged’ to her, and indeed Miss Gilkicker had been Cornelia’s prop in the aftermath of her mother’s death, although Cornelia would never have described her as such. The gap in age between the sisters also meant that it was impossible to teach them together, the one struggling with French irregular verbs, and the other with her letters. Little Isabelle had spent the two years before Cornelia went to stay with her aunt, largely excluded from the schoolroom, where the presence of a little girl under the age of six was ‘not conducive to Miss Cornelia’s acquisition of knowledge’. Colonel Wareham accepted the situation and had given Sileby the duty of being his younger daughter’s guard dog, since his valeting tasks were not onerous. It had been Sileby who stopped her falling in the pond, led her first pony, and anointed the grazes that were the natural consequence of a small child running about. When Cornelia had left home, Miss Gilkicker had taken charge of Isabelle, but a bond remained, one which was re-established and strengthened when daughter and valet had worked together so long in the course of caring for the ailing colonel.

Sileby had always been there, always been a fount of solid common sense, and letting him go seemed an added loss, a finality of accepting her father’s absence. He himself had hinted at the problem on several occasions, asking what she would like him to do, but she had brushed it away, always for another day. When he knocked and asked if he might speak with her this day, she knew it was unfair to do nothing.

‘Yes, of course Sileby, do come in, and take a seat also.’ She saw him bridle. He had been her father’s soldier servant from his first service at the end of the war in America until he retired at the time of the brief peace in 1802. Colonel Wareham had sold out and come to Bradings, which he inherited from an uncle. Isabelle had been a small child and could not remember anything of the life before this house. ‘Please, do sit.’

He sat, as if at attention, perched on the edge of a chair, his capable hands placed side by side on his knees.

‘What am I to do, miss? You know as well as I do, there is no work for me now the Colonel has gone.’

‘Oh, Sileby, I know and yet … Is there not some other role you can assume here?’

‘Now, what could an old soldier like me do, Miss Isabelle? I looked after the Colonel for thirty-eight years. I am not a groom, nor a butler, as if Wellow was not able to do his job, which he is.’

‘But you are part of the family, Sileby, the family of this place.’

‘I am not here to be idle like an expensive ornament, Miss Isabelle.’

‘No indeed, but … Where would you go?’

‘That I couldn’t say. I’ve no relations as I know of. Last saw my sister before we went off to Holland, over in Kent that was.’

Isabelle felt at a loss and sighed, but then an idea struck her.

‘What about the Lodge?’

‘The Colonel never replaced the old chap who used to live there, years back. Gates haven’t been shut in three years at the least. You’ve no call to have a lodge keeper, Miss Isabelle.’

‘But it would give you somewhere to live, somewhere close by, and I know my father made provision for a pension in his Will. Filey sent me a copy of the whole of it. If you took up the Lodge, made it habitable again, that and the pension would keep you very tidily. Mrs Frampton would be happy to have you still at table, I am sure, and there are times when dear Wellow needs another pair of hands to move things, and you know he would never trust the outdoor staff not to be clumsy.’

Sileby frowned. It would be easy to say yes, but he did not want to take advantage of Miss Isabelle’s youth and inexperience. He had known her all her life and understood now was a difficult time. As a sop to his conscience, he accepted the offer on a temporary basis, ‘until things settled down’. The relieved smile on her face made him feel better, and worse. He admitted as much to Mrs Frampton, below stairs.

‘Well, she’s right enough about you being welcome here, as well you know,’ Mrs Frampton assured him.

‘Ah, but it’s a crying shame for the poor young lady. Here’s she been, hidden away here all these years, and now who does she know? Us three old ’uns, and you cannot count the maids and such, Sir Charles up at the Hall, and old Lady Monkton, who’s older ’n all of us.’

‘I thought perhaps she and Sir Charles might make a match of it once, but he treats her like a brother would,’ sighed Mrs Frampton.

‘Nice enough fellow is Sir Charles, but Miss would run rings round him. She needs a man with more in his noddle than her cousin. Old Sir John was nobody’s fool, but her ladyship … Ah, now there’s a butterfly-brained lady if ever there was.’ Wellow added his mite to the conversation. ‘I reckon as it is from her Sir Charles gets it, and Miss Julia even worse. Mind you, if Miss Julia were home, she would give Miss Isabelle company her own age.’

‘From what I hear from the Hall, there’s high hopes for Miss Julia contracting a very good alliance.’ Mrs Frampton was on good terms with the housekeeper at the Hall. ‘When the Season ended, she went off to Worthing with her Grandmama, and a likely gentleman followed her there. She is visiting with her ladyship in Shropshire, where he is likely to inherit. The word at the Hall is that there will be an engagement before Christmas.’

‘Which will leave Miss Isabelle even more isolated. Perhaps she should have gone off with Lady Dunsfold after all.’ Sileby looked glum.

‘No, no,’ Wellow shook his head. ‘Better for her, and us too, she does not go to her ladyship at Lincombe to be treated like she was dirt. Never was any sisterly feeling between them, as well we know.’

Meanwhile, the object of their concern was wondering whether it was worth having a fire kindled in the dining room for her to eat there, or whether she might as well eat at the little supper table in the small parlour which had doubled as the schoolroom. Isabelle had been a bright pupil and enjoyed learning, but Miss Gilkicker had always been, in her own mind, Cornelia’s governess, and there had been no strong bond between them. It had seemed perfectly natural that Cornelia should have called Miss Gilkicker to inculcate the basis of learning into her son before he was sent off to school, and Isabelle had been too busy in the early days after her father’s seizure to have time for the finishing touches that Miss Gilkicker would have liked to give to her education. The schoolroom had become Isabelle’s private parlour to which Colonel Wareham had been wheeled to give a change of view and take tea on summer afternoons. He was used to saying that she held court there but if that was so, he was her only courtier.

She was dragged from her cogitations by the sound of the bell ringing from the front hall. A minute or so later Wellow announced Sir Charles Wareham, and her cousin, muddied of boot and in riding dress, strode into the room with a cheery greeting. Isabelle requested the burgundy to be brought in for her guest, and tea for herself. Sir Charles grinned.

‘You are the perfect hostess, coz. I just thought I would pay you a little visit on my way back from Devizes. Er, has Mrs Frampton been baking her almond tarts?’

‘I am sure if she has, Wellow will bring a plate of them, for everyone knows how susceptible you are to them.’

‘Mrs Frampton has a magic touch with almond tarts.’

‘So you really only came to see if there were any you might devour?’ Isabelle smiled, and then laughed as her cousin coloured and demurred. It was not a thing she had done much in recent weeks.

‘No, no! Isabelle, you wretched girl, you are roasting me as always. It is no way to speak to “the Head of the Family”.’ He attempted to look serious and failed.

‘Dear Charlie, you only remember me when there is another reason that connects, and the thought of Mrs Frampton’s almond tarts must have been it.’

‘Actually, you are wrong.’ His amiable features settled into a more serious expression. ‘The thing is, Isabelle, what about Christmas?’

She looked perplexed and repeated the word.

‘Uncle George always had the hunt meet here Boxing Day, and then a day’s shooting about Twelfth Night. His coverts were always good. But in the circumstances …’

‘Oh! Goodness, I had not considered even as far as Christmas, but you are right. It is impossible for me to hunt, of course, or entertain properly, but there is no reason why the hunt might not meet here, and arranging the day’s shooting would give me something to do, you know. I am sure it would not be considered improper for me to let it take place since I would be expected to remain out of the way. I got used to it with Papa. We would see everyone at the first stand down by the Home Wood, then watch them go off, and hear the guns, of course, and at the end of the day they would return and describe their day to him over mulled wine and pies. That last part might be difficult, I suppose, but your mama might be able to act as hostess perhaps?’

‘She might. Not back with Julia as yet, you see. To be honest, I think Slinfold needed to feel his old grandfather approved of his choice before popping the question. I count it a bit lily-livered of him, but, no doubt he calls it filial duty, or is that grand-filial duty?’

‘I did get a letter from Julia just before …’ Isabelle paused for a moment, and then continued. ‘She did seem in remarkably good spirits and described Lord Slinfold in glowing terms.’

‘Good enough fellow, Slinfold, but you know, the sort who takes his fences but is secretly yearning to go by the gate instead. His heart isn’t in the jump. Julia will lead him a merry dance if he lets her, and I fear he will.’ Sir Charles shook his head in brotherly concern. ‘But we stray from the point. The hunt is simply a matter of telling the Master to carry on as normal. When it comes to the shooting it is a bit different.’

‘Give me a list of those who normally come, Charlie, and I will write letters, rather than send out cards of invitation. If I couch it in terms that Papa would wish this tradition to continue, and it would be a form of memorial to him, it would not sound forward. Of course, include any guests of yours who are with you over Christmas.’ She looked up as Wellow returned with refreshments. Mrs Frampton clearly believed Sir Charles to be suffering from starvation, she thought, for besides almond tarts, there was a pound cake and shortbread. ‘You have cheered me up, Charlie, and here is your just reward. I hope your horse is strong enough to carry you with all the extra weight afterwards.’

He grinned.

‘You sound yourself again, Isabelle, just a little.’

Her face clouded.

‘Oh. Should I, Charlie? Is it not too soon?’ She sounded guilty and he came and took her hand, pressing her gently onto the sofa.

‘You should. It is what your Papa would have wished, that you look forward, live your life.’ He looked very earnestly at her. ‘I do understand, Isabelle, the feeling that anything but grief is wrong. I felt it after my father died, and you were closer to yours than I was to mine, through necessity and being just the two of you here. Uncle George once told me his only regret these last years was that he had been blessed by your company, but in doing so had kept you from the youth you deserved.’

‘What nonsense.’ She frowned.

‘No, he was right. Quite a downy one, Uncle George. My father always said the brains of the family passed him by and went to his brother. A girl of your age should have had a Season, been presented at Courtlike Cornelia was. At the age she was perfecting her curtsey and poring over fashion plates and ribbons, you were taking up running Bradings and caring for your Papa. You went from girl to lady of the house almost overnight.’

‘I would not have had it any other way, Charlie, you know that.’

‘I know’ he squeezed her hand, ‘but I am telling you the truth. You wear your blacks but you must not linger in black gloom, or think that laughing is dishonouring your father’s memory. He wanted you to be happy. When you laugh, you do as he would want.’

She tried to smile but her lip trembled, and he put an arm about her shoulder and gave her a cousinly hug.

‘Things will get better, you wait and see.’

Sir Charles was a country gentleman at heart and had not spent the Season in London for some years. He preferred hunting game in his coverts to chasing Covent Garden ‘ladybirds’, and a hand of picquet, with a good claret from his own cellars set at his elbow, to an evening losing his blunt in White’s. He did, however, like to have his coats made in Town, and so the following week, whilst Isabelle tried to begin preparations for a very isolated Christmas at which she could be, at best, a sad spectator, he drove up to London, stopping overnight at Newbury. Upon entering Weston’s premises, he heard a voice he thought he recognised, and he waved away the employee bowing before him to look around the corner to where a tall gentleman in military uniform was being measured. His scarlet coat was laid over a chair.

‘Idsworth! Good God! Haven’t seen you since I was hauled up for putting that piglet in the Master’s lodgings, and it made a terrible mess of his new Persian carpet. You said it would have been better if I had found a lamb.’ He paused. ‘You know, I thought you were dead, old fellow.’

The gentleman turned, thereby forcing a pin into his arm, but barely registered it nor the tutting of the tailor.

‘Wareham? As you can see not dead yet, despite every attempt Boney’s finest made upon me. It is good to see a face I recognise.’ He smiled.

‘Well, if you will be in London in November, what do you expect? Very thin of company. You after evening togs or …?’

‘Sold out, and it is nine years since I wore anything but uniform. Not sure any of my old clothes even fit me now.’

Charles Wareham’s memory was good but not swift. He remembered now what had happened to his friend from Cambridge. Idsworth was two years his senior and had gone down at the end of his first year. What had then occurred had all been rather messy and embarrassing, and Julian Westerham, Earl of Idsworth, had disappeared into a line regiment.

‘No, I don’t suppose they do, all that running about killing Frenchmen would put muscles on a fellow for sure.’

‘If you would just stand still a moment longer, my lord,’ the tailor murmured, still with a pin in his hand.

‘I am sorry. Of course.’ Idsworth stood still, but even when relaxed clearly had the demeanour of a man used to standing at attention.

His companion in youthful misdemeanours had changed, thought Wareham, but then he had been only twenty-one when he left England for Portugal, proud possessor of a sword, a lieutenant’s commission, and very little else. The boy had become the man, not only in stature. He was a fraction taller than all those years ago, no longer gangly and loose-limbed, but broader of chest and firmer of thigh. His face was more sombre as well as weathered, the grey-blue eyes more guarded. The naive youth who had gone unsuspecting into society from Cambridge had learnt more than just how to survive in battle.

‘So where are you off to after London?’ Sir Charles enquired.

‘I am not destitute, Wareham, I promise you.’ There was a slight snap to Lord Idsworth’s voice.

‘I did not mean …’ The younger man was slightly taken aback.

‘No, of course you did not. I apologise.’ Idsworth smiled lopsidedly. ‘I suppose I am too much on the defensive, in enemy territory, or so it feels. I will return to Buriton, to the Dower House. That was kept on, and my aunt lived in it until her death last year. Buriton Park itself is leased for two more years, and then … It will be a start.’

Charles Wareham was a kind-hearted man and saw the shadow of loneliness pass over Idsworth’s features.

‘I don’t suppose you have met up with many of your old cronies as yet, but Christmas is fast approaching, and you cannot spend that alone. Come down to Baddesley Hall and spend it with me. We don’t do anything fancy. It will be my mother, my sister, oh and “Molly” Mollington. Not sure if you know him.’

Lord Idsworth frowned at the unexpected offer.

‘Very decent of you. Not sure I should …’

‘Do say yes, there’s a good man. Be delighted to have you. Might as well have somewhere to show off the new toggery, eh?’ Wareham beamed, and in the face of such genuine kindness, Lord Idsworth agreed to come into Wiltshire a week before Christmas.

CHAPTER THREE

The prospect of Christmas did not in itself buoy Isabelle’s spirits. The season was one for family, and being together, and she faced the very first without her father. They had kept the Feast of the Nativity quietly enough but it had been happy, nonetheless. Even in the worst of weather she and Sileby had managed to get Colonel Wareham to the church services, and he had taken to having the staff come up to the dining room and sharing a huge bowl of hot punch with them Christmas evening. He told Isabelle it cost nothing to show gratitude, and though working for him was their paid employment, he was conscious that they all did so with cheerfulness, and never begrudged the extra work his infirmity put upon them. Isabelle would do the same this year, but it would feel more like a wake.

There had been the small distraction of Sileby taking over the little lodge cottage. Isabelle had herself gone to see what needed to be done to make the place habitable after several years without an occupant, and then sent the under housemaid and the gardener’s lad to assist, returning once Sileby was installed with his personal possessions, which seemed to her meagre.

‘What needs have I for clutter, Miss Isabelle? I am used to campaigning, and you travel best if you travel light.’

‘But this is not campaigning, Sileby. This is now your home.’ She did not add that she wanted him to feel so at home that he would not wish to move. ‘There is not even a mat before the fire, nor an upholstered chair, which is odd, because I am sure there was one when I came a week ago.’

‘That there was, Miss Isabelle, but it had the worm something bad and collapsed when Sukie tried to sit in it. Not that I need something soft to sit upon.’

‘Well, I refuse to think of you living here sat upon a stool or that dining chair. There is a Windsor chair in the small parlour that is actually in the way. I shall have that sent down, and when next I get to Chippenham, I shall purchase material for a new pair of curtains. Those are mildew stained and not thick enough to keep in the warmth on these cold winter days. What size would you say they were?’

‘I’m not a tender plant, Miss, so don’t you fret about me.’ Sileby was touched but embarrassed.

‘No, no. New curtains, I insist.’

The old retainer recognised her tone and gave in gracefully. He was not surprised that his mistress ordered the carriage the next clement day, nor that the curtains appeared within a week thereafter, though he did not know that she had hemmed them herself, much to Mrs Frampton’s horror. That lady did admit to Wellow that, however demeaning it might sound, not that she would breathe a word to anyone else, she could see it gave poor Miss Isabelle something to occupy her besides sitting all sorrowful. It was true, but Isabelle had other things which would take her attention in the coming weeks.

Since the hall and dining room were public rooms and would be seen by those who returned from the New Year shoot, Isabelle contemplated their decoration with greenery for the festive season and discussed it with Wellow. She then awaited Sir Charles’ list of those she should invite for the shooting. Some she remembered from previous years, and although Wellow shook his head over her spending so much time at her father’s desk, and sending the groom hither and yon with her missives, it did give her occupation. The first letter was to the Master of the Hunt, and since he had known her since infancy, it was not merely a formal communication. His response was swift, avuncular and positive, and Isabelle was cheered by it.

It was the second week in December when Wellow interrupted a detailed discussion between herself and Mrs Frampton on what viands should be prepared for the shooting party with the unwelcome announcement that Mr Semington had called to visit her. Isabelle groaned but accepted that she ought to see him, since he had ridden over specially. Mrs Frampton withdrew to her kitchen realm, and Mr Semington entered. There was always something about the way he did so which implied that it was only a matter of time before he would do so by right of ownership, a right which extended to Isabelle. She found it both intensely annoying and vaguely disquieting, and it made her sharp with him.

‘Good morning, Edwin. I am quite busy today, so I may not linger in idle chatter.’

Neither her words nor acerbic tone seemed to affect his self-confidence.

‘Ah yes, my dear, a woman’s work is never done, is it. I am so glad to see you engaged in activity again, not moping aimlessly.’

Isabelle resented being told that her moping was aimless by another, whatever she had told herself.

‘And what highly important tasks have you been about?’ She raised an eyebrow.

‘Business, my dear. Business that you would not understand.’

‘Really?’ Isabelle nearly ground her teeth in frustration.

‘Actually, Isabelle,’ he continued, ‘I am here today to invite you to Pescombe for Christmas day. Mama and I agreed it would be kind to take you from your solitude for a day.’

He made her sound like a charity case. The trouble was that she had no reasonable cause to refuse this highly unwelcome offer.

‘Well, it is very kind of Mrs …’

‘… but Isabelle is already engaged to spend the day with us up at the Hall, aren’t you, coz?’

Sir Charles strode in without being announced, which irritated Semington, as Wellow knew it would when he ushered him into the room.

‘I … Yes, I am, and so although it is so very kind of Mrs Semington to think of me, I have to decline the offer. Do thank her for me, Edwin, and thank you too, of course,’ Isabelle lied, without compunction.

Mr Semington’s self-belief would not admit the rather obvious nature of the falsehood. Sir Charles was, however, having difficulty in keeping a perfectly straight face.

‘Ah, then perhaps at New Year?’

‘We shall see, Edwin. I have the shooting party to organise.’

‘You are not hosting that without your father, surely? A young lady in your situation? Alone?’ Semington sounded slightly shocked, which pleased Isabelle the more.

‘Not quite. My aunt will receive any gentlemen who come into the house after the shoot for refreshment, and the luncheon is being taken out in hampers.’ Reluctantly, she knew she could not fail to invite her father’s godson, though he was an awful shot, and she wished to avoid him as much as possible. ‘Do say you will join us, on the sixth.’

‘Of course. Delighted. As always.’ He puffed out his chest, as if accepting the role of guest of honour.

Sir Charles very nearly sniggered, and Isabelle, unwilling to let open acrimony break out, gave her cousin a warning frown. He retrieved his place in her good graces by ensuring Semington’s departure by the simple expedient of claiming to have to discuss a matter arising from the Trust.

‘Private affairs, Semington. I am sure you understand.’ He went and held open the door.

Edwin Semington had no choice but to retire gracefully.

‘You are a wicked liar, Charlie.’ Isabelle gave in to a wide smile.

‘Only a bit. I was going to invite you to the Hall for Christmas and I’ll be da—dashed if I will let that puffed-up prig ruin your day. And as for lying, you made a pretty good job when I gave you the chance.’ He pushed his voice up an octave. ‘And thank you toooooo.’ He choked, and coughed.

‘Serves you right. I do not sound at all like that. It will be all right for me to attend do you think? In my blacks? I am not meant to go to parties and such.’

‘You are family. What sort of relations would we be to leave our cousin on her own at Christmas? Besides, it is only us and Lord Mollington, whom you may have met last Easter, and Lord Idsworth, who has been away serving King and Country these past nine years and has just sold out. No, it is not really a social gathering and nobody could take exception to it. At least,’ he qualified his statement, ‘I would not think anyone around here would do so.’