7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

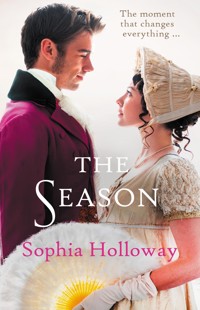

The moment that changes everything . Henrietta Gaydon is making her debut in London society for the Season, but her popularity and apparent ease disguises the fact that she is out of her depth and that she dreads the objective of finding a husband. She longs for home, her father and Lord Henfield, who she has always treated as an older brother. Charles Henfield stopped thinking of Henrietta like a sister when she was sixteen. And he is determined to try his luck with her in London. Mistakes and misunderstandings, the complication of a feud between mamas, and Henrietta's no longer fraternal feelings for Henfield, all conspire to make this a Season to remember.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 430

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE SEASON

SOPHIA HOLLOWAY

For K. M. L. B.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

‘I have received a letter from your Aunt Elstead, my dear.’ Sir John Gaydon looked up from his perusal of the missive, held at arm’s length both to facilitate his reading and to keep the peculiarly scented paper from his nose. He smiled at his daughter.

‘How is my aunt, Papa?’ Miss Henrietta Gaydon put down the sock she was darning in a housewifely manner.

‘Well, very well, as it appears you will be able to see for yourself, quite soon.’

‘She is coming to visit us?’ Henrietta was astounded, since she could not actually recall having met her aunt since her mother’s funeral, some eight years previously.

‘No, Henrietta, you are going to see her. I … you are eighteen, ready to make your curtsey before the polite world, and your aunt has kindly agreed to present you this Season, with your cousin Caroline.’

‘You mean go to London?’ Henrietta made it sound as if it were St Petersburg.

‘Yes, of course. It would be unfair, even cruel of me, to keep you cooped up here, and prevent you making your mark, taking advantage of meeting … people.’ In truth, Sir John did not relish the idea of losing his daughter to a husband, but recognised it was selfishness on his part.

‘London,’ repeated Henrietta, in an awed voice. ‘Almack’s?’

‘I cannot conceive why not. I am sure your aunt will be procuring vouchers for your cousin.’

‘But what shall I wear?’

‘Gowns.’ Sir John blinked at the question, which, as a man, he took quite literally. ‘No need to fear there are not sufficient funds put by to cover your junketing about. Your aunt was always quite the fashionable lady, and will rig you out in fine style.’

Henrietta sat down in the nearest chair in a manner that the lady would no doubt have considered lacking in deportment.

‘I cannot believe it, Papa. I had thought perhaps the local assemblies …’

‘Your dear mama would have wanted you to have your Season, be presented at court as she was, and you are a dashed pretty girl, very like her in her youth. You will be a great success, as long as you remember not to consider yourself “a great success”.’ Observing her stunned expression, he rang for tea. However, when the door was opened, it was not the butler who entered, but a well-set-up young man of above average height, with dark chestnut hair, a ready smile and such ease as might have made him appear the son of the family. He came forward, hand outstretched, as Sir John rose from his chair.

‘Good afternoon, sir. No, no, please do not get up. I thought I might drop by to tell you that I met Mr Preston on the Ludlow road, and he said his pointer bitch has had a fine litter, and you can have your pick, or rather Henry can, as promised.’ He looked to Henrietta, who clapped her hands together.

‘Oh, Charles, how wo … but if I am going to London …’

‘London?’

‘Yes, my boy, Henrietta is off to dazzle in the firmament of society. Oh, there you are, Stone.’ The butler had entered. ‘Would you bring tea, please.’ His gaze reverted to his godson. ‘You will stay and take “tea and excitement”, won’t you, Charles?’

‘Er, yes, yes of course.’ Lord Henfield appeared almost as taken aback as Henrietta, but made a recovery. ‘Foolish of me not to have considered you disappearing for the Season, Henry. I am sure you will have a wonderful time. Just do not let some buck in yellow pantaloons turn your head with his finery, eh?’ His smile was broad, but his eyes did not echo the pleasure to quite the same degree. He took a seat to the right of the fire, and extended cold hands to its warmth, feigning preoccupation with the act of getting the blood flowing back in them. He had known Henrietta from her infancy, and she and his godfather were as ‘close family’ to him, with both his parents having deceased in the first five years after he attained his majority. He would miss her.

‘So what shall I do about the puppy? It was very kind of Mr Preston to remember how much I admired his pointer, and to offer us one of her litter, but if I am in London …’ Henrietta bit her lip.

‘I think he would understand, Henry, honestly. If you like I will take you over to The Chestnuts just before you go, and you can have a look at the litter and make your choice, assuming they are not yet ready to leave their mother. The Season is not so long that you will not be back within a few months, and if it is here already, well, you will have missed it looking all big eyes and uncoordinated paws but that is all. It will grow to accept you easily enough.’ Like her sire, Lord Henfield preferred not to think that London would be other than an interlude of pleasure. ‘The puppy might even keep your papa company in your absence.’

‘Really, Charles?’ Henrietta giggled. ‘So I am as much company as a dog? Charming. Papa, I refuse to sit at your feet and beg for treats, just so as you know.’

‘No, Henry, you know I didn’t mean … obnoxious girl. You will have to learn to be much more formal and polite for London. No treating poor decent fellows as you do me.’ Lord Henfield gave her a look of mock reproach, at which she wrinkled up her pretty little nose.

‘I shall be very polite, because I shall be treated with politeness, sir.’ She stuck her chin in the air, but her lips twitched.

Sir John shook his head and laughed at the pair of them.

‘So when are you leaving?’ Lord Henfield enquired.

‘Papa?’ Henrietta looked at her father. ‘You did not say when.’

‘You are expected in South Audley Street in three weeks.’

‘Oh my goodness! What shall I do?’

‘Start packing?’ suggested her friend, his lips twitching at her expression.

‘But I have not got clothes suitable for London.’ One hand went to her cheek.

‘That is why your Aunt Elstead wants you settled so soon, so that she may, let me see …’ Sir John picked up the letter once more. ‘Ah yes, “ensure her wardrobe does her justice”.’

‘Do not worry, Henry. You will take London by storm, not a doubt of it, and do us proud.’ Lord Henfield gave her a wry grin.

She assured them she would try very hard to make them proud, but doubted very much that London would find her anything out of the ordinary.

Henrietta alternated between wild excitement, nervousness, and gloom. She was counting the days, but both eager for adventure, and cast into misery at the thought of leaving her papa. Lord Henfield was somewhat surprised to find her in the latter mood when he drove her over to The Chestnuts, and Mr Preston, to select the pointer puppy.

‘You know, it may not be ideal, Henry, but it will soon recognise you as mistress once you get back, and it really will give your papa something to make a fuss of while you are away.’

‘I told you before that he does not fondle my ears or tell me off for hiding bones under the library rug, you know, but you are right, and I ought to be pleased. We have missed a dog since old Rufus died, and he had got to be too old to go out with Papa when he went shooting.’

‘Then why such a long face? I would think you would be like a cat on hot coals, eager to experience the capital.’

‘Oh yes, yes I am, but …’

‘But …?’ He cast her a sidelong glance. She did have a most enchanting profile, he admitted to himself.

‘I have never been away, not for more than a week with my grandmama, after Mama … It feels like … desertion.’

‘Ah.’

‘And I do not know my Aunt Elstead, beyond recognising her if she walked into the room.’ Henrietta sighed.

‘Ah.’

‘The “ahs” are not helping, Charles.’

‘Sorry, Henry. I suppose the nearest I can think of was going off to school, which was pretty dashed scary at the time. One wondered, as you do, about fitting in, making friends and all that, but you know, it just “happens”, and you have to remember that all the other young ladies will be nervous and feeling vulnerable too. And there is even the advantage of not getting thrashed at all-too-frequent intervals.’

‘It is different for men.’

‘She says, from great experience.’ He smiled at her.

‘But when they “go to Town” they generally do so after university, and have a wide acquaintance among their peers.’

‘And have less guidance, not that it would be popular at the time. We all thought ourselves very grown-up and were no more so than … pups. We therefore tumbled into a few scrapes, but learned a lot.’

‘I cannot imagine you in a scrape, Charles.’ She looked at him, his face open and honest. She could not think of him engaged in the least devilry.

‘I do not know whether that delights me or horrifies me. Do you think I am too virtuous, or too boring?’

‘You are never boring. Charles, and as for virtuous … virtue may sound boring but actually it is to be applauded, since vice is to be deplored.’

‘I once let a chicken into the master’s lodgings when I was up at Oxford,’ admitted Lord Henfield confidingly.

‘Well, sir, if that is the limit of your vice …’

‘Er, and its three “friends”. One laid an egg under the master’s wing chair.’

‘Most reprehensible.’ Henrietta’s lips twitched. ‘Were you apprehended?’

‘I confessed, and did “penance” by clearing up the mess, and you would be amazed how much mess four hens can create, and having to write an ode, in the style of Horace, “To a Chicken”.’

‘Goodness! I am sure that taught you a lesson, and not in Latin.’ She bit her lip to prevent herself giggling the more.

‘It put me off poultry, unless cooked.’ He had coaxed her from her sad mood, which had been his intention, and they arrived at Mr Preston’s both in good humour.

Mr Preston greeted them with a combination of warmth and deference, having known both since childhood and himself being in the lower echelons of the local squirearchy. He escorted them personally to the hay-scented loose-box where Tilly, his pointer bitch, was suckling her litter of seven. She looked up at her master’s arrival, and the thump of her docked tail showed her greeting. Henrietta was content to watch the family for a few minutes, then squatted down and spoke softly. Tilly appeared unconcerned, and the pups, sufficiently fed to start snuffling about, began to play. One puppy came towards her, cautiously at first, taking her scent, tail wagging in a hopeful manner. Henrietta extended her hand and the puppy nosed it, then licked it experimentally, and sneezed.

‘I told you wearing pepper was not a normal perfume,’ observed Lord Henfield mendaciously.

Mr Preston reached and picked the puppy up. Tilly watched, but did not move.

‘Nice little bitch, this one. Not shy, interested in what is about, and nice short back and good head. She should make a good working dog like her mother.’

‘She is very pretty also.’ Henrietta stroked one velvety, liver-brown ear. The puppy had a light flea-bitten colour coat with splashes of liver-brown on shoulder and haunch, and a ‘cap’ that extended over both ears and cheeks. ‘Might we have this one, when she is old enough to leave her mother?’

‘Of course you may, Miss Henrietta. I will bring her over to The Court when weaned.’

‘I am afraid I will be absent then, Mr Preston, for I am going to London, to stay with my aunt, Lady Elstead, but I do look forward to seeing this little one when I return. Dido, that will be her name.’

‘Dido it is then, Miss Henrietta.’

‘Remember to tell your papa, Henrietta, or the poor thing may get most confused if he names it Thistle.’ Lord Henfield was in funning mood.

On the journey back, however, Henrietta, having extolled the visible virtues of the puppy all she might, became quiet. Eventually she spoke.

‘When I am away, Charles, will you look after Papa for me?’

‘He is scarcely in his dotage and enfeebled, my dear girl.’

‘No, but it has been just us, him and me, for some years, and … He treats you as he would a son.’

‘He has always been most kind and generous of time and advice, but a “son” …’

‘You count as part of the family, to him, to me too, Charles. I trust nobody more than I do you.’ Henrietta put his lack of response and compressed lips down to the taking of a sharp bend without much reduction in pace.

Came the day, came the tears, and if the majority were from Henrietta, then her father’s eyes could not be said to be dry either. Lord Henfield, who had walked over to bid her farewell, remained dry-eyed, however. He said little, believing it a time for father and daughter, with himself upon the fringes, but when it came time to hand her up into the waiting post-chaise, it was he who took her hand. She looked up at him, her lashes wet, bravely trying to smile at him. His expression became of a sudden quite serious.

‘Spread your wings, Henry, and enjoy all that is new, but remember we are here for you still,’ he murmured, in his soft baritone. He paused, and then pressed something into her gloved hand. ‘You will have jewels suitable for a young lady, items from your mama, but this belonged to mine, and I would like you to have it.’

Henrietta blinked at the brooch in her palm, a gold disc in which a frond of leaves was set in pearls.

‘Oh Charles, you should not. I cannot …’

‘You can, and I beg that you will.’ He closed her fingers over it, and she, blushing, stood upon tiptoe and kissed his cold cheek.

‘I will miss you too, you know,’ she said softly.

‘Only until that first dance, fickle Miss Gaydon,’ he replied, hiding his own embarrassment. ‘Now, off with you.’ He handed her into the chaise, and watched her arrange her skirts, then closed the door.

The horses were set in motion. Henrietta leaned to wave and keep her father in sight as long as possible, but the curve of the drive eventually hid the two gentlemen from view. She dabbed at her eyes, sniffed, and looked again at the brooch. She was, she decided, a very fortunate young woman to have a doting papa and such a kind friend.

When Henrietta reached South Audley Street on the third day, having spent two nights upon the road, she was weary of body, and disinclined to eat, her constitution, she decided, not being best suited to prolonged travel. Indeed, upon a few patches of post road she had felt quite unwell, and it was a rather pale young woman who alighted before the Elstead residence, and trod, a little stiffly, up the steps.

Her aunt greeted her warmly, and fussed over her tiredness, concealing at the same time her disappointment. When last she had seen Henrietta, a formless little girl of ten years, she had features which clearly showed her maternal lineage, but had her sire’s brown hair and looked likely to follow him in being, although not stocky, ‘solid’ in build. The young woman before her, despite a pallor from travelling, and a tired droop to her shoulders, was possessed of a figure that would draw admiring glances, and a face that would make those glances stares, at least among the impertinent. She was not, perhaps, as tall as some men liked, and her hair was still ‘brown’, but of a shade that made the word seem inappropriate for one so beautiful. Lady Elstead had expected to bring out her daughter with her niece a little in the background, but faced the fact, squarely, that Caroline, brunette and pretty as she was, could not hold a candle to her cousin. It was most lowering.

She voiced this complaint to her lord, having sent Henrietta up to rest and take supper in her room, if she could not face coming down to dinner.

‘It is most vexatious, and it is no secret that Sir John’s estate passes to her upon his demise, and a healthy estate that is. I almost wish I had not made the offer to bring her out … But my poor sister trusted me to do so, come the time, and one has one’s duty to the family.’ She sighed, both indicating the sorrow at the loss of her sibling, and at the burden now placed upon her.

‘Well, my dear, in some ways it is no harm done. A girl can only marry one man, and a man may only marry one girl, so if there are plenty hovering about Henrietta, then Caroline will also be in their milieu, and …’

‘You would have our daughter take her cousin’s “cast offs”?’ snorted Lady Elstead.

‘No. I am simply saying there are enough young men to go around. Caroline is a pretty girl, and will do well.’

‘“Well” may not be good enough, sir.’

‘What is it you want for Caroline? Surely a decent husband, of good family and with sufficient wherewithal to keep her in comfort, is enough. The Season ought not to be a competition to see which girl “wins” the highest rank or the wealthiest husband.’

Lady Elstead did not reply, since she wisely realised that the male perspective was not that of every Society mama. Rank was not everything, nor was wealth, but both counted for more than their obvious advantages. Every woman sought to be a success at her own come-out, and then prove her worth by launching any daughters in such a way that they in turn achieved a brilliant marriage.

‘Get Henrietta off your hands and you will see Caroline follow suit,’ declared Lord Elstead. His lady looked thoughtful. ‘Trust me on this.’

‘I hope you are right, my lord, but … yes, I will trust you.’

Lady Elstead went to her bed, putting from her mind any unchristian thoughts of showing Henrietta off in unbecoming gowns, or hinting at an inclination to the consumptive habit. In fact, the opposite was true.

CHAPTER TWO

When Henrietta awoke next morning, it was only upon full consciousness that she realised where she lay. The bed was comfortable, much more so than those at the posting houses upon her journey, be the sheets never so aired, and she stretched luxuriously. A fire was already alight in the grate, and Henrietta, normally a light sleeper, acknowledged just how tired she must have been. She rang for her maid, and hoped Sewell, who had found fault with almost everything beyond the borders of Shropshire on their journey, would be in a more positive frame of mind. In this she was to be disappointed.

‘Never have I been in such a noisy, unwholesome place in all my born days, Miss Henrietta.’

‘I slept very well,’ offered Henrietta.

‘Yes, miss, but you was done to a cow’s thumb, as well I know, and would have slept sound if the house itself had taken fire. Now, will you be wishful to take your breakfast in your bed or …’

‘Oh no, I think it only polite to present myself properly before my aunt at a good hour. I fear that yesterday I was monosyllabic, and besides, I wish to make the acquaintance of my cousins.’

Her aunt had informed her that whilst of course the younger Felbridges were still at their studies, in school or at the Elstead family seat, both Caroline and James, Caroline’s elder brother, were in residence, and eager to meet their cousin. It had only been a pity that Caroline was at a dressmaker’s fitting, and James not yet returned from an engagement with one of his friends. Refreshed by slumber, Henrietta was hoping she would match their expectations.

When she went downstairs and was shown to the breakfast parlour by the butler, who introduced himself as Barlow, she found only the Honourable James Felbridge at his repast. He almost jumped to his feet, and, had anyone asked, would have instantly declared that his cousin far outstripped any expectations he had of her, although those had been very vague. That her gown was not in this year’s fashion, and her hair styled in a manner that had echoes of the schoolroom about it, struck him not at all. What he beheld, as he later confided to his crony Mr Carshalton, was ‘a vision’. He swallowed hard, twice, and made her a bow.

‘I believe you must be my cousin James,’ said Henrietta, making her curtsey and then offering him her hand. She had expected him to shake it, but he, after a moment’s hesitation, bent over it and kissed it rather formally. Henrietta looked surprised. ‘Oh.’

‘Indeed, and mighty honoured I am to make your acquaintance, Cousin Henrietta. I was told you had arrived, but that you were fatigued by the journey.’

‘Alas, I must sound very feeble.’

‘Not at all. Long way from Staffordshire, and …’

‘Shropshire,’ she corrected.

‘Long way from there too. You must have been fagged to death. You are recovered now, though?’

‘Oh yes, and my appetite has returned also.’

‘Appetite … breakfast, yes, must eat.’ He showed her the selection of covered dishes, and was most attentive, to the point where she reminded him that his own breakfast was being neglected.

‘It is of no matter, cousin.’

‘You say that, but wait until your eggs are cold and congealed and you will not think so.’ Henrietta smiled, and a dimple peeped.

When Lady Elstead entered the parlour a few minutes later it was to find the son and heir already in a fair way to being besotted, which was a thing she had not for an instant considered. Her arrival curtailed his adoration, and she had no compunction in dismissing him upon the excuse that he had evidently finished eating and she wished to discuss the day’s plan with Henrietta. Once he had withdrawn, her ladyship settled herself with tea and toast, and looked at her niece.

‘So, my dear. You look to be recovered.’

‘Indeed, ma’am, I feel very much more the thing this morning and can only apologise if I seemed …’

‘No, no, my dear child.’ Her aunt raised a hand. ‘I perfectly understand how exhausted you must have felt.’ There was a short pause. ‘You have not been to London before, have you.’

‘No, ma’am, no further than Grandmama Gaydon, in Cheshire.’

‘Well, I have no doubt it will seem very strange at the first, but you will soon get used to it. You must, of course, remember that going about alone is unthinkable, not as at home, where I am sure you were at liberty to exercise unescorted. Wherever you go, if you are not accompanied by myself, or another chaperone, you must take a maid, or a footman. To appear “forward” is an unforgivable sin in the eyes of society, and would blight any chance you have of making a suitable connection.’

For one moment Henrietta’s mind went blank, and then the full import of what had been said hit her. She had, in some strange way, thought of this visit as an adventure, a rite of passage even, but here was the nub of the matter. Her aunt saw it as society would see it, as the way to arrange her future, to find her a husband. A small but insistent voice within her cried out that she wanted to go back to Shropshire, carry on just being Papa’s daughter.

‘Does it shock you, my dear? It is, alas, the great problem when one has not a mama to guide one. One has to be pragmatic. When a young lady makes her curtsey to society, it is also her chief opportunity to secure her future, and a future means being married, having an establishment of one’s own. In the next few months you will meet many gentlemen, and it is almost certain that one amongst them will find you just to his taste, and he to yours. The days when marriages were arranged without either party having any knowledge of the other are thankfully consigned to the past, in most cases. Neither I nor your papa would expect you to marry a man you could not respect, nor hold in less than a firm regard. You are a beautiful girl, and if your manners and character are equally appealing, you will do very well, very well indeed, and we may expect an excellent match.’ Lady Elstead regarded the round gown with disfavour. ‘Of course, in order to show you at your best, it will be necessary to get you to a decent dressmaker before anyone sees just how … but it is not your fault, my dear, not at all, and your hair, well, my maid can arrange it before we go out shopping. You are no longer a child in the schoolroom. We will have you quite presentable before you have to go abroad in public.’

Henrietta felt rather flattened by all this. She had realised that her wardrobe was not up to London standards, but this sounded as if she was dressed so abysmally that being seen with her would be an embarrassment.

‘I … I will be guided by you, ma’am, of course. I have brought my jewel casket with me, with such pieces as Mama left to me. I am not sure if there is a “fashion” for jewellery, but I can assure you that the quality is good.’ She looked so downcast that Lady Elstead took pity upon her.

‘If you inherited them from your mama, I know they will be beautiful. The art, with a girl in her first Season, is not to overdress with trumpery pieces, or large and gaudy stones. “Pearls are perfect, diamonds desirable”, that is what I hold to, and so should you.’

‘I have a pearl necklet, and drop earrings, and a diamond pendant and hair ornament, and a few brooches.’

‘There. You have at least just what you need in that department. Now, where has Caroline got to, I wonder? Much of her wardrobe is complete, but I saw the most fetching hat yesterday, and we might as well visit milliners together, yes?’

Henrietta merely nodded. Lady Elstead rang to send a servant to ascertain if her daughter was awake, and shortly afterwards that damsel appeared, was introduced, and sent to prepare for an assault upon the emporia of the capital. This clearly appealed. By the time the trio returned for a late luncheon, Henrietta’s mind was a whirl not just of chip straw and ruched linings, but, courtesy of several modistes, of sarsenet, spider gauze, vandyke and scalloped edgings, twills, satins and figured muslins.

Before dinner. Henrietta sat down to write to her papa, to reassure him of her safe arrival, and to warn him that she was undoubtedly making him poor.

… I am not sure that I have any say in the matter, my dear Papa, for I have no notion how many gowns one ought to have, nor of what stuffs. I shall not bore you with describing such things, for I know that it would tell you nothing, since you would have no image of what I meant, unless I were to send you the latest edition of La Belle Assemblée. I confess my own understanding is rather jumbled at present, but I will be learning very fast, about as fast as the guineas disappear from your account! My aunt has also declared my hair to be dressed so badly that she had to have her maid attend to it before I went out in public, even wearing a hat. I have returned this afternoon already the proud possessor of no less than four hats, an opera cloak, a merino spencer, a pair of long kid evening gloves, three pairs of gloves for day wear, a spangled shawl and half a dozen pairs of silk stockings. The dressmakers are attending to the gowns, which must be adjusted to make them fit perfectly. If you were to see me next week, dear Papa, you might not recognise your own daughter.

I cannot say as yet that I like London, for I have not attended any parties, or visited any important sights, but I have been continually busy. I slept most soundly the first night through tiredness, but it is noisy here until very late, and I am unused to voices outside, and the constant sound of hooves upon the cobbles.

I have met my cousins, who are both very friendly. Cousin James is about to enjoy his first Season, having graduated last summer. You must tell Charles that he was quite correct, and young gentlemen embarking upon life in the Ton are definitely ‘pups’. He will know what I mean and explain it to you. What surprises me is that Cousin James seems so tongue-tied with me, since he has sisters. Charles was never so awkward, and he has no siblings whatsoever. Cousin Caroline is very pretty, and has a soft voice. My first thought was that she is shy, but it turns out that she is not, but merely possessed of the soft tone of voice. We have discovered that we share the same tastes in poetry (which will make Charles shake his head, since he hates Lord Byron’s poems) and look awful in anything pink. I think we shall be the best of friends. My Uncle Elstead will be franking this for me, but he is going back to his estates for several weeks Tuesday next, so I may have to send letters crossed, Papa, though I know you find them difficult to decipher.

I miss you terribly, but I am trying not to mope, and indeed, I am sure that once I am engaged at parties and not sat about thinking, I shall be happy enough. Tell Charles that I hope to write to him also in the near future.

Do send me all the news from home, especially when Mr Preston brings Dido to you. She was the sweetest puppy, Papa, and so bold and interested.

I must close now and dress for dinner. If I give this to my uncle it may be on its way to you in the morning.

I remain, dearest Papa, Your devoted daughter, Henrietta

As she addressed the letter she wiped away a tear and sniffed, but had regained her composure by the time she joined her relations before dinner. It was the first time that she had met Lord Elstead, and although her first impression of him was that he was a trifle severe in demeanour, he went out of his way to be amiable, and by the time the ladies withdrew, she was much more at her ease with him, and thought him very sensible.

It could not be said that the pace of Henrietta’s life became any less hectic over the next week. Lady Elstead engaged a dancing master to ensure that the two young ladies would not disgrace themselves with the waltz, should they be given leave to dance it, and to improve their other dance steps so that they might complete the figures without concentrating upon them. She was only very slightly irritated that Henrietta turned out to be the better of the two. She had to remind herself that Henrietta had little French, by her own admission, and had never essayed the harp at all. There were dress fittings, and for shoes, morning calls which left Henrietta wondering how many new acquaintances she had made, and ‘lessons’ from Lady Elstead, who reminded both girls that they needed to know the relationships between the most important society figures, since it was so easy to praise a lady’s sworn foe in an attempt to be polite, and thereby raise the auditor’s hackles.

‘One has to be not just polite, my dears, but politic, and that is rather different. Avoiding embarrassment is far easier than trying to brazen out a faux pas.’

Henrietta and Caroline nodded obediently. There were, it seemed, pitfalls of which they had been entirely ignorant. Lady Elstead was, of course, planning her campaign with the grim determination of a general in the field, as was every other matchmaking mama. Even friends, if bringing out daughters, might be classed as ‘enemy’ this Season, and, having surveyed quite a few of the ‘opposition’ during the reconnaissance that was the morning call, Lady Elstead had already identified several ‘allies’, ladies with girls who were either patently less attractive and would be honoured to form part of the Elstead circle, or such contrasts that each would show off the other. If a gentleman was only attracted to fair damsels, there was nothing that a brunette might do, and vice versa. Placing one’s pretty brunette next to an equally attractive golden-haired maiden could show off both.

Lady Elstead did not, of course, reveal her plan to Henrietta and Caroline, and her ‘lists’ were kept even more closely to her matronly bosom. That Lady Elstead was a ‘list maker’ was known to her entire family and household staff. Lists were, to her, wondrous things, the writing of which gave substance to aims, form to formless ideas. She made lists for everything, from the contents of her jewel casket, with an additional one noting when each item was last cleaned or repaired, to those who had sent invitations over the last two Seasons, annotated as ‘accepted’, ‘declined’ and ‘unable’. The ‘unables’ were those where some unforeseen event had prevented attendance at a function she had graciously accepted. Of course, some lists were mundane, but the ‘suitors’ lists were most secret. Before the Season even began she had considered various single gentlemen of the Ton who would be suitable for her Caroline, and also those who would obtain her hand only over her own dead body. The list that she drew up for Henrietta was not identical, since, despite her maternal lineage, Henrietta was a Gaydon, not a Felbridge, and there were nuances, undercurrents.

She was proud of her ‘suitors’ lists. She thought them neither ridiculously ambitious, nor timid. They were not, of course, prescriptive. Should one of the gentlemen she accounted beyond touch show interest, she would add him with a flourish. She wanted a good match for both her protégées, but Caroline’s future was the dearer to her, naturally.

‘A man can only marry one girl’, her lord had said, and this had given Lady Elstead pause. Her initial reaction to Henrietta’s beauty had been adverse, but now she had amended her ‘Henrietta list’ she was more sanguine. Henrietta might have less polish, not having had the benefit of her own advice over the last few years, but she had greater beauty, and an inheritance that would not have every fortune hunter in Town on the doorstep, but would make a ‘mere baronet’s daughter’ a far greater catch than otherwise. There were certainly a number of gentlemen of decent breeding but rather modest means, whose lack of wealth kept them from the list for Caroline, but would be perfectly acceptable for Henrietta. The girl would not suffer, since she would live as well as she had previously, and the gentleman would see his family fortunes boosted, perhaps restored. Not that she would advocate a wastrel, an inveterate gambler, but some men had fathers who had squandered riches, mamas who had proved ‘expensive in the extreme’. Some of these gentlemen were even reduced to marrying nobodies, tainted by commerce and trade. How much better would be a beautiful bride, of impeccable background. Yes, this brought some interesting names onto the list, and such gentlemen would be eager to secure such a prize, which would mean them applying for her hand quite early in the Season. Lady Elstead spent a happy half hour imagining the cachet that would attend her having found a match for her niece before the Season was half over, to be followed by a brilliant match for her daughter. The following half hour she permitted herself the luxury of drawing up a putative wedding invitation list designed to pay off many old scores.

In blissful ignorance, the two girls formed a very cousinly friendship. To Henrietta, as an only child, and with no close female friends, this was quite a novel situation, and she put out the feelers of friendship almost tentatively. She was used to fitting in with a male world, and being ‘girlish’ was almost something she needed to learn. Caroline was a little taken aback by Henrietta’s almost ‘boyish’ attitude, since she was rather more forthright than most girls, but her mama reminded her that her ‘poor cousin’ had lacked the guiding hand of a mama since the age of ten, and had been brought up in a household with only her papa, and visits from his male acquaintance.

‘I do not say that Henrietta is fatally rustic, you understand, for she is remarkably well behaved, but she is unused to the company of ladies, and has, perforce, copied a slightly more “mannish” way of going on. I am trusting you, my child, to show her how a delicately brought up female comports herself in conversation.’

As far as Cousin Caroline could see, the only problem with Henrietta’s manner was that she clearly thought that ‘beating about the bush’ was sometimes ridiculous, if not verging on the dishonest.

‘Do you expect me to tell lies, Caroline?’

‘No, no, it is just … think of it like the dance, cousin. One could walk across the dance floor in a few paces, but that would not show off one’s abilities, nor be entertaining. By using the steps, following what is expected, we show ourselves at our best. So if someone were to ask your opinion of a new book, or picture, saying “I thought it mediocre” is too blunt. One must try and say a few nice things about it, without overpraising.’

‘What if I cannot think of anything?’ Henrietta had a smile on her lips but a frown between her brows.

‘Make something up.’

‘But that is the lie, Caroline.’

‘I think you are going to discover there are a lot of lies in the London Season, my dear cousin.’

CHAPTER THREE

Sir John received his beloved daughter’s first letter, thankfully not crossed, within a week of her departure from his gate. It both cheered him, knowing that she was safe and well, and left him dispirited, because the house felt empty without her youthful and optimistic presence. It was illogical, he told himself, to think that the absence of one person rendered his house ‘empty’, but he could not remark to the servants about the small things he noted on his daily walk, nor invite the butler to play chess with him. Lord Henfield came over several times, and one afternoon they went out to shoot rabbits, but it had to be said that Charles was not his usual self either, and although he put a brave enough face upon it, he appeared a trifle low spirited.

The letter was read to him when he came for dinner, was dissected and smiled over, and both gentlemen reminisced about their very mildly misspent youths whilst considering ‘pups’.

‘At least I think we can be sure Henrietta will not be bowled over by her cousin,’ declared Sir John.

‘Most definitely not,’ agreed Lord Henfield, gazing at the contents of his brandy glass as if it might produce some unexpected augury.

‘One wants to see her settled and happy, of course, but, you know, Charles, the thought of her gone, perhaps residing at the other end of the country, quite fills me with gloom.’ Sir Charles was watching his godson quite closely.

‘Mm.’ It was clear that Lord Henfield found the thought equally unappealing.

‘She is not an angel. I never pretended she was, because at times she can drive a man of sense to distraction, wilful miss that she can be, but … she has a spark. Her mother had it, God rest her, and … I miss her damnably, and she has only been away a week.’

‘Mm.’ This time the ‘mm’ was more distant.

‘Are you listening, Charles?’

‘Mm. I mean, I am sorry, thoughts drifted off for a moment, must be your devilish good brandy.’ It was a lie, but a soft one. Lord Henfield was imagining Henrietta, eyes sparkling, on the arm of some faceless man whom he hated for merely existing.

‘I was saying how much I missed her.’

‘Perfectly natural that you do, sir. Be a good thing when Preston brings over that puppy. Give you something to write about to Henry, and something to talk to.’

‘As long as it does not answer back, eh?’

‘Absolutely.’ Lord Henfield poured them both another brandy.

Lord Henfield received his own letter from Henrietta a week later. He looked at her neat, still rather schoolgirl hand, and it brought back another letter from her adolescence, one he had kept, and in which she had been so upset and apologetic at angering him. There were no tear stains on this missive.

My dear Charles,

You never warned me that London does not sleep! Of course we are likely to be abroad in the early hours, but there is bustling about from dawn, and what with vendors in the streets, and link boys and horses, it makes one wish so much for the peace of the country. I have been forced to take to my bed for an hour some afternoons, which I would never do at home unless ill. I do not wish you to think, however, that I am not enjoying myself tremendously, even before attending any of the Ton parties. I never have to wonder what to do with myself, and Green Park and Hyde Park provide welcome places where one might walk. Taking one of the maids with me means dawdling, alas, so I prefer to take one of the footmen. They always seem glad to be obliging, which must mean that they enjoy fresh air too.

Lord Henfield groaned. Trust Henry not to see that footmen were as impressionable as other men.

My cousins are delightful, although Cousin James speaks too often in half sentences. His papa is very proud that he obtained a ‘very sound’ degree from Cambridge, but sometimes I wonder if his wits are lacking. Of course it might be that he is actually thinking very important thoughts, and not paying attention to what he is saying to me. You were so very right about ‘pups’, and he counts as one. Now, I wonder if I threw a stick in the park, would he fetch it for me? Am I not wicked?

We attended the opera last night. I very much enjoyed the singing, but was so glad my uncle had procured us a box. I do not think the gentlemen in the stalls were attending properly during the arias. I did not mention this to my aunt because I have now been in Town nearly a week, and I am learning things. Gentlemen, when together and without ladies present, are inclined to drink rather too much. James looked very ‘unwell’ yesterday, and his mama was not at all sympathetic. I was at first shocked, since I thought she would be most concerned, but she simply told me that his disorder was self-inflicted, and that we should ignore it, and indeed him, for the rest of the day.

I have had fittings for new gowns, and my hair has been cut and is being dressed differently, so I do not think you would recognise me at first glance. I am definitely not a ‘schoolroom miss’ any more, and you will have to treat me like a real lady when next we meet, or at least try to do so.

Has Dido come to The Court yet? I do so hope Papa likes her, and that you are looking after Papa too.

Yours always, Henry

At least she still signed herself that, he thought. He had always called her ‘Henry’. The trouble was he was realising why, and that was because it kept up the lie that she was not actually a girl, just ‘Henry’. He had known it for a lie these two years past, increasingly so, but had kept up the pretence to himself. At the same time, because he was the only person who used the name, it implied their closeness, and special bond. Now she was gone, and he was faced with the harsh truth that when she came back it might be only briefly, and as a prelude to becoming another man’s wife. ‘Yours always’ would be meaningless then. He sent his reply to catch the mail coach from Ludlow.

My dear Henry,

Or is that appellation unsuited to your new ‘grown-up’ status? I was not sure that you would have believed me if I had told you how tiring the capital can be. I do not think you feeble for taking a rest in the afternoons, and indeed would advocate that you do so, so that the pace may not tell upon your constitution. I recall some young ladies looking positively wan by the time they were presented at court.

You are quite correct that gentlemen are inclined to drink too much, but not in general when there are ladies present. However, by the end of an evening, even at a ball, I would not trust to many being entirely sober. Thankfully, most gentlemen learn to hold their drink. It sounds as if your cousin, especially if he has been a good student, has yet to acquire that ability. Do not tease him over it, but do as your aunt says, and pretend not to see.

He frowned. Was he sounding too avuncular, giving advice? He changed the subject.

Dido arrived yesterday, and has already chewed one of the slippers you made for your papa last Christmas and tipped up a three-parts-empty coal scuttle, at which point she became a very black puppy. Your papa appears delighted, but then it was not he who had to bath the animal. I believe Thomas was not so happy.

I have been a most frequent visitor but I cannot replace you, my dear Henry. Your papa does very well, but we both miss you very much.

You may have changed the styling of your hair, and your gowns, but I trust you to remain the girl we both hold in such deep affection.

Yours, Charles

For a moment he wondered if he had said too much. No, she would take it to mean fraternal affection.

Whilst the Season was still comparatively quiet, Lady Elstead brought her daughter and niece gently into society, first by attending an evening party hosted by old friends, friends who had known Caroline as she grew up. This meant that Caroline was less overawed. It was, however, an important occasion, and both she and Henrietta were excessively excited to be dressing for their first ‘grown-up’ party, and inclined to be wide-eyed. Lady Elstead watched, but said nothing. This, after all, was why she was introducing them at a comparatively small social event, so that they might get the novelty of it out of their systems. After three or four evenings out, they should have gained a little poise. She recalled her own first party, and did not think them foolish. If tonight they stammered their responses for the first hour, and blushed, then they would be forgiven.

‘You know, Maria, I am so glad I am not eighteen, are not you?’ their hostess remarked quietly, partway through the evening. ‘We managed it then, but it all looks so perfectly exhausting now.’

‘Oh yes, and yet … The first time a gentleman sent one flowers …’ Maria Elstead sighed. ‘Being young is wonderful … once. I fear chaperoning the young is also going to be exhausting, though, and without the bouquets.’

‘Ah yes, but you will have far greater prizes, seeing them safely betrothed.’

‘Very true, Charlotte.’

‘And two such pretty girls too. Your niece is set to inherit her father’s entire estate, you say?’

‘She is.’ Lady Elstead saw her opportunity. ‘One would not describe her as a great heiress of course … but … None of the estate is entailed.’ Thus were sown the seeds, without her ever telling anything other than the truth. Knowing her hostess, this information would spread swiftly enough, and with just a little gilding. Nobody would be so mercenary or impolite as to ask the exact size of the estate, or the figure of its worth, and by not claiming too much, which would be found out by some busybody, just sufficient interest would be raised to give Henrietta’s chances a little boost. She had beauty, birth and now bounty.

Henrietta herself was in total ignorance of such machinations, and was simply enjoying being part of a new and overwhelmingly exciting world. Her host introduced her to his nephew, Lord Netheravon, who possessed a head of golden curls, and a fine figure. His fair lashes blinked over startlingly blue eyes, and, although Caroline later suggested that he was an Adonis, Henrietta was more inclined to see him as a remarkably athletic cherub. He was patently impressed with her own looks, and made every effort to entertain her. He was droll, self-deprecating and had sufficiently outgrown the ‘pup’ stage that condemned her cousin James to being treated as a younger, rather than older, relative.

‘So, Miss Gaydon, this is your introduction to the Season. I hope you are not already bored?’

‘Bored, my lord? How could one be bored?’

‘But my dear young lady, cultivating at least the appearance of being bored is half the “act” of the damsel at her come-out. Mark my words, in three weeks you will be complaining at “such awful squeezes”’ – he pitched his voice unnaturally high – ‘and “positively interminable suppers”. You all do it, every year, upon my honour, even if you would not swap these entertainments for a casket of rubies.’

‘I shall not, my lord,’ she assured him, dimpling, which he found entrancing.

‘But you have to be, lest you be pointed out as “idiosyncratic”. “There is Miss Gaydon,” they would say, “who is so original. She loves every bruised toe, every worn heel, every syllabub and syllable of the Season”.’

‘But why not enjoy it?’

‘Fashion, Miss Gaydon, fashion.’

‘Then I think I may choose to be unfashionable, my lord.’