Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

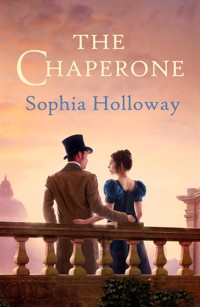

Sophy Hadlow does not want to return for another London Season. Her own debut into Society was marred by self-consciousness and her cringing embarrassment every time she was announced as 'The Lady Sophronia Hadlow'. Yet, much to her dismay, Sophy is back in London to oversee the debut of her younger sister and their wild cousin, Susan Tyneham, who risks ruining both her own and her innocent cousin's chances of marriage. Sophy, a most reluctant chaperone, is left to guide her sister and attempt to keep Susan from complete disaster, all whilst dealing with her own unexpected feelings for the disarming Lord Rothley.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE CHAPERONE

SOPHIA HOLLOWAY

For K M L B

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

‘N o, Mama, surely you do not mean it.’

‘I am sorry, my dear, but I really see no alternative.’ Lady Chelmarsh looked at her eldest child, not without sympathy. ‘If I am to bring out your cousin Susan at the same time as Harriet, then I will need assistance, especially if Frances has need of me as her time draws near. You are old enough and sensible enough to guide the girls for a couple of weeks and your sister will need—’

‘Am I advanced in years, Mama?’

‘Maturity, Sophronia, would be the word I would use. Your maturity will make it perfectly acceptable for me to do so.’

Sophy Hadlow pulled a face. She had absolutely no wish to spend another Season in London. She was a young woman who laboured under several disadvantages, not the least of which, in her own opinion, was having a name which made her wince. Thankfully, only her mother ever called her Sophronia at home, and she was perfectly happy as Sophy, though less so as ‘Soppy’, which name her younger brother Jasper, Viscount Elvington, used when he wanted to annoy her. However, hearing her name announced in ringing tones at society functions as ‘Lady Sophronia Hadlow’ always made her shrink. Perhaps her mama had felt a premonition at her birth that shrinking might be useful, for her other major problem was her height. Sophy stood nearly five foot ten in her stockinged feet, and stood out like a sore thumb at parties among the other debutantes. Lady Chelmarsh had known even before attempting to launch her first-born into society that it would not be easy. Whilst Sophy was still in the schoolroom she had shaken her head over her chances, and at one stage even suggested to her lord that they put Sophronia on a strict diet. He had vetoed this idea on the sound grounds that whilst it might make the poor girl hungry and emaciated it would not decrease her height. A tall man himself, the Earl of Chelmarsh could not fully appreciate the problem.

Lady Chelmarsh had given up, but always tried to get Sophy to bend her knees when standing with other young ladies. This made her very self-conscious about her looks, and gave her a strained back. Her mama never ceased telling her how difficult she made things for herself, as if her stature was her own fault. Added to her height, which was mostly accounted for by long legs, Sophy was possessed not of a maypole figure, but one rather more generously endowed in the bosom than would be expected of so slim a lady. The fashion of gowns accentuated both her height and bosom, and her mama despaired, predicting failure, which duly ensued. Lacking confidence and made constantly aware of her ‘oddity’, Sophy crept miserably through her first Season, and then a second and third when her younger sister Frances was brought out.

Frances was a more average height, a little on the tall side, perhaps, but only by the smallest of margins. She basked in maternal approval and formed a very suitable connection within the year. Young Lady Tattersett had then proceeded to fulfil wifely expectations within eighteen months of marriage and was due to be confined for the first time in early May.

Sophy had determinedly avoided a pointless return to London since her sister’s triumph, and had not thought it necessary that she should attend for the come-out of her youngest sister, Harriet, six years her junior. The death of Lady Chelmarsh’s sister, however, meant that her ladyship faced guiding two inexperienced damsels, and felt the need for reinforcements.

‘What about Aunt Augusta? She would be far more help than I could be, Mama.’

‘Your Aunt Augusta has declined.’ Lady Chelmarsh coloured, not wishing to reveal the tone of her sister-in-law’s refusal, nor her reason.

Sophy was about to ask why, but noted the look upon her mother’s face, and thought the better of it. Aunt Augusta, Lady Warsash, was a very strict and proper individual, and from what Sophy could remember of her cousin Susan when last she had seen her, the two would not get on well. Susan bore every sign of being an ill-disciplined romp of a girl, and it was only from a strong sense of sisterly duty that Lady Chelmarsh had agreed to bring her out, since Susan’s older, and far more staid, brother, the current Lord Tyneham, was still single.

‘Would it not be possible to delay Harriet’s coming-out for a year, and Susan’s also? Frances is unlikely to produce another infant within twelve months of the first, surely.’

‘No, I will not have Harriet dawdling about at home. She is far too pretty a girl, and already young Minsterley, and half the neighbourhood, are hanging about our gates.’

This was an exaggeration. Harriet was very popular with the young men with whom she had grown up, and who now noticed that she was no longer a fubsy schoolroom miss, but a fledgling beauty, although none were to be found lingering by the lodge in the hope of a mere sight of her.

‘Besides, Susan will be nineteen before the Season is half over. If she is to be launched into Society at all this is her chance.’

‘At all, Mama?’

‘I meant,’ Lady Chelmarsh corrected herself, rather hurriedly, ‘that if she is to make a good match, she cannot afford to be twenty.’ She said the number as if it were three score years and ten.

‘I am three and twenty, Mama,’ murmured Sophy.

‘Yes, my dear, but … some girls are not destined for marriage. One never quite gives up hope but … And do not think I do not appreciate you, for I do. I was only saying to your father the other day what a consolation it is to know that we have you on hand to keep us young, when we get older.’

Sophy did not find this very cheering. Being a prop to one’s ageing parents did not strike her as an ambition in life. Not that she could lay claim to having any ambitions of her own. Once, perhaps, she had dreamt of being swept off her feet by a tall, and she always counted that as important, handsome man who would worship the ground upon which she trod, and whisk her away to a neatly proportioned country seat where the chimneys did not smoke, and they could live in blissful union for the rest of their lives. Her first Season had shown her how unlikely an eventuality that was. Her mother clearly thought her a lost cause in the marriage market, but then she always had been most pessimistic about her chances.

Lady Chelmarsh’s thoughts had moved on to matters of the moment, and she asked Sophy if she had seen her tatting, which was really an instruction for her daughter to go in search of it.

Lady Harriet Hadlow was too old for the schoolroom. She told herself this, even as she sat in it, daydreaming about a spectacularly successful debut in the adult world. Since the departure of the governess, this had become a quiet refuge from the bustle that surrounded the preparations for a London Season. It was all terribly exciting, of course, but gave little time for imagining, and Lady Harriet was a natural dreamer. Mama had already said that they would take up residence in Hill Street early enough to visit the most fashionable modistes for most of her dresses, and she had brought several recent copies of La Belle Assemblée to provide her with inspiration. The fashion plates depicted gowns more suited to dashing young matrons than modest debutantes, but there were several in which she could see herself stunning the most apparently hard-hearted, but secretly romantic, eligible gentlemen, who would combine title, riches, handsome features and a capacity for love.

She heard footsteps in the passageway, and her sister popped her head around the door.

‘I thought you would be here, Harry. Has Mama told you that I am being dragged to London too?’

‘Oh yes,’ declared that damsel, blithely revealing that Lady Chelmarsh had informed other members of the family before telling Sophy herself. ‘Mama said you would dislike it, but that must be a hum, because how could you prefer staying here with Papa and his stud books, or whatever you call them for cows? There will be nobody interesting left in the vicinity, and you would be reduced to mending flounces and inviting as dinner guests old Sir Humphrey Mawdsley, who sneezes snuff over one, or Lady Wadderton, with her ear trumpet.’

It had to be said, Lady Harriet did not paint a picture of pleasure and excitement.

‘But Lady Wadderton tells such funny stories. That one about the effete vicomte and the roses …’ Sophy’s lips twitched.

‘Oh yes, that one, or the one about the carriage that bolted. Those are the two stories she always tells. Alternatively, there is the one about how she saw her cousin ‘in flagrante’ with her aunt’s coachman, in an arbour at Ranelagh Gardens. I only heard that one the once, when Mama had started inviting me to join her when she had visitors to take tea, at this time last year. Mama spilt milk over her green Berlin silk.’ Harriet sounded quite matter-of-fact. ‘I did ask Miss Welling what “in flagrante” meant, when I returned here, but she boxed my ears,’ she added, pensively.

‘Yes, well, anyway, I would prefer the boring mediocrity of life at home to gadding about to parties where I will stand against the wall and be expected to chaperone Susan.’

‘Oh, it will be such fun having Susan with us. She is so lively and exuberant.’

‘Harry, our cousin Susan is wild. She does not know the meaning of the word decorum.’ On the other hand, Sophy thought it quite likely that she would have had no need to ask a governess what ‘in flagrante’ meant. ‘If you wish to fulfil Mama’s expectations, and to be admired by gentlemen who might make you an offer, you will not ape her manners. Aunt Clarissa indulged her far too much from an early age, and she never had the benefit of a governess who remained as a steady influence, as Miss Welling did with us.’

‘I remember when we met the year before last, just before Aunt Clarissa died, Susan said she had “survived” eight different governesses.’

‘She probably meant literally. Trying to educate her would easily have driven any governess possessing nerves to an early grave. It must have been quite traumatic.’

‘She did say that she got rid of her first one by putting a frog in her soup and a dead mouse in her bed.’ Harriet giggled, and Sophy gave her a look so repressive that she said it rivalled Mama’s.

‘I am being serious, Harry. I have this dread of Susan landing in all sorts of scrapes, and the danger is that her behaviour will reflect on us, on you, and damage your chances.’ Sophy took her youngest sister’s hand. ‘You will be like Frances, Harry, and make a very good match.’

‘Sophy,’ Harriet avoided looking her eldest sister in the eye, ‘does Frances love Lord Tattersett?’

‘What sort of a question is that?’

‘An honest one. When we visited her before Christmas, and she said she was increasing, she looked more worried than radiant.’

‘It is her first time, Harry, and I expect she is nervous, and at that time she was still feeling sickly. That is why Mama is going to her in April, to help her prepare. She was certainly exceedingly fond of Tattersett when they married, and her letters to me have never indicated that her feelings have changed at all.’

‘I do not want to marry a man I do not love. Would Mama make me do so?’ Harriet looked at Sophy, a little uncertainly.

‘No. I am sure she would not, Harry, at least not a man whom you could not love. I have seen a great many young ladies marry men of whom they were merely very fond, and when they have got to know them better, after marriage, they have learnt to love them. I think the idea that love hits one as a coup de foudre is a myth perpetuated in those lurid romances which Miss Welling forbade you to read, and which you borrowed from Eliza Sapperton and hid under your bed.’

‘You knew? And did not tell?’

‘I knew. And I am not a sneak. I trusted that you would read them, but be a sensible girl and see them for what they were, nonsensical fairy tales with no relation to reality.’

‘Oh, of course not. I mean, there are no such things as headless monks, and young ladies are not chained in dungeons full of bats.’ Harriet frowned. ‘At least, not in England. But some of the heroes were very brave and dashing.’

‘There is not much call for gentlemen to be brave and dashing at Almack’s or in Hyde Park. One has to content oneself with polite and thoughtful.’

‘But would it not be wonderful to be rescued by a hero, Sophy?’

‘No, because in order to do so, one would have to be in peril, which would undoubtedly be most unpleasant.’

‘I fear you are not a romantic, Sophy.’

‘Which is also a good thing, since if I were I would be a very disappointed one.’

She saw Harriet’s face fall, and smiled.

‘I am sorry, Harry, do I depress you? It is not my intention. You will have a very enjoyable time in London, except that you will learn what it is to have feet that ache from dancing, and if you do not turn heads you may call me …’

‘Sophronia.’

‘Hmm.’

It was later that afternoon when she knocked upon the study door, and was invited to enter by her sire. Lord Chelmarsh was reading correspondence, and looked up with a smile.

‘Sophy, my dear.’ He saw her expression. ‘You wish to unburden yourself, I see.’

‘Am I that transparent, Papa?’ She smiled, wryly.

‘To me, yes.’

Sophy was deeply attached to her father, and looked up to him, not only in respect but literally. She had, she supposed, always found it reassuring that she had one member of her family who remained taller than she was.

‘London, Papa.’ She sighed. ‘I really do not want to go.’

‘Your mama feels the need for your support, Sophy.’

His daughter did not enquire about him giving support. Lord Chelmarsh rarely went up to Town, preferring to spend his time in improving his estates. His correspondents and friends were men of similar interests whom he would not find in London except under duress. He immersed himself in cattle breeding and his lady wife was sometimes heard to complain that he held his prize bulls in greater esteem than his children. This was not true, quite.

‘I am not sure that I will not simply be there merely to keep Susan out of mischief.’

‘Of course that is why you will be there. Your cousin is … wilful and innocent, which is a dangerous combination in a girl her age.’

‘You say that, Papa,’ Sophy laughed, ‘as if it were a trait to be bred out, as you do with poor milkers.’

‘Might be easier for everyone if it could be, my dear.’

He invited her to sit, and studied her face. He could not see why she had never ‘taken’. Her hair was somewhere between brown and gold, her complexion healthy and unblemished, and her features good, with a straight nose, naturally arching brows, and remarkably fine, blue green eyes. Her mouth might be considered fractionally too large for perfection, but it was a mouth used to smiling at the world, except when in London.

‘London will surely not be so bad, Sophy. You assuredly will not find a husband here.’

‘You know as well as I do that I do not go for that reason. I know Mama despairs of getting me off your hands. She is now talking of me as a prop for your declining years.’

‘I can think of few things less appealing than to become a prop. Marriage would save you from that. I would like to see you mistress of your own establishment, setting up your nursery, but that does not mean I would see you wed to anyone less than a man for whom you cared deeply, and most certainly I do not seek “getting you off my hands”.’ There was an edge of mild reproof in his voice.

‘I am sorry, Papa, but … if you only knew how much I detest being on show. I hope you realise it is all your fault too.’

‘Mine?’

‘Yes, sir, since it is from you I inherit my excessive inches, and you were mightily remiss in permitting Mama to name me after her godmother, which I know was in some expectation of largesse which never materialised.’

‘The first was beyond my control, and de facto, the second also. It is very difficult to impose a name upon a child, when the mother is in the euphoria of relief at having survived, and simultaneously cast down by the perceived failure of not being delivered of a son.’

‘Yet she did not give Frances a cumbersome name, and it was only after her that Jasper arrived.’ Sophy ignored the idea that her not being a boy was a failure on her mother’s part.

‘Very true. I have to admit that I did put my foot down at her first choice.’

‘Which was?’

‘Euphemia. Sounds like “euphemism” to me. Ghastly name.’

‘And Sophronia is not?’

‘It is easily shortened to Sophy, which I happen to like.’

‘As do I, Papa,’ she laid her hand on his, ‘but in public I am always announced as Sophronia. If only you had been a mere viscount, I could have been simply “Miss Hadlow” and been comfortable.’

‘But by that reasoning, the fault lies with your grandfather for not living beyond his seventieth year, for until then I was a viscount, and at birth you were “Miss Hadlow”.’

‘Being right and reasonable is not fair, Papa. I am neither, but it is how I feel.’

‘And do you “feel” better for having had the opportunity to vent your complaints?’

‘Yes, Papa, for you do at least listen.’ She sighed.

‘I listen, but I do not change things when it comes to matters better understood by your mama. To London you will still go, but try to do so with a more positive outlook. If you are fortunate, Mama will be so taken up with launching Harriet and Susan into Polite Society that she may not notice if you chance upon a suitable beau of your own choosing. You are a good girl, Sophy, and if the world was fair, which it is not, you would undoubtedly find one. Your mother’s efforts were perhaps too self-conscious. See what happens when you leave the matter to fate.’

‘My fate, Papa, will be to be Mama’s scapegoat when my unrestrainable cousin proves to be … unrestrainable.’

CHAPTER TWO

The Honourable Susan Tyneham sat with her hands folded in her lap, deceptively demure. Her brother, some eight years her senior, sat opposite her, his face stony. There had been an altercation when they had set off upon their journey, and it had concluded with each side still holding the same views as at the outset. Lord Tyneham, a slightly stocky but not ill-favoured young man, had withdrawn into dignified silence. Susan had decided that to look daggers at him would be a waste, and frowning would incline her brow to wrinkles, so she taunted him by looking as angelic as he knew she was not.

There was little to mark them as brother and sister, and if the old gossip was true, their relationship did not extend to having the same paternity. Lady Tyneham had been a beauty in her youth, and in the eyes of the world had married well, for Tyneham was an exceptionally wealthy man, although only a baron. Upon his marriage he had lavished that wealth upon his bride; his wealth but not his affection, and affection was what she craved above all things. Lady Tyneham had dutifully presented him with an heir within the year, after which their mutual incompatibility had been denied by neither party.

Whilst this meant that his lordship resumed much the same life he had as a single man, paying for his pleasures with a succession of attractive but demanding and expensive barques of frailty, his lady had become a lonely figure among the young matrons on the social circuit. It was some years afterwards that she came into the orbit of a charming but casual lover, with whom, despite the advice of older and wiser heads who warned her of his reputation, she had enjoyed a passionate and barely concealed alliance. He had treated her as the centre of his universe for one whole Season, but at its end, however, he had dropped her as if they had never been upon more than terms of nodding acquaintanceship. She withdrew to Tyneham Court, broken-hearted and carrying a child whom everyone believed was not her lord’s. Since the fruit of this illicit union was only a girl, Tyneham was content to appear ‘generous’ and keep both his spouse and the child, whom he saw as a constant reminder to his erring wife of the penalties of infidelity. To the world he announced his paternity, and dared them to say otherwise. They did not say, but they whispered, and Lady Tyneham did not return to London again, even after her husband died, some thirteen years later.

It might have been assumed that she would have resented the little girl, but with her son sent away to school, and a husband who largely ignored her, but who kept her almost exclusively in the country, she focussed her love on the only person left to her. Susan was indulged. Susan was never reprimanded. Susan became the ‘household god’ whom none dared gainsay. She seemed to have inherited more than suspiciously dark locks, which gave the lie to the sandy-haired baron’s protestations. Her character, unrestrained, was wayward, selfish and bold to the point of being heedless. Upon the death of Lady Tyneham, some eighteen months previously, her elder brother had been put in the difficult position of guardian, and had taken the line of least effort, leaving his sister in the care of the last, and most resilient, of her governesses. Pretending she was just a child helped, but in the locality of Tyneham Court, Miss Tyneham was regarded as dangerous.

Now Aunt Chelmarsh was going to bring Susan out, and hopefully find her a husband who could assume the burden of responsibility for her. Tyneham would be so very glad to wash his hands of his troublesome sister. She was a beauty, and he would ensure that she came with a sizeable dowry, so it ought not to be too hard to find a man who would overlook her faults, thought Lord Tyneham, gazing dispassionately at her, as long as he did not know her too well.

They arrived in Hill Street a little after four. When the liveried groom assisted Miss Tyneham from the carriage, she threw him a look which would haunt his dreams for weeks, and made his insides go weak, and she swept into the house with a smile lurking in her eyes. Men were so easy.

Lady Chelmarsh greeted her nephew with mild pleasure, and her niece with barely concealed trepidation. Susan made her curtsey prettily enough, but as she raised her eyes to her aunt’s face, Lady Chelmarsh could see the spark of rebellion in them. She reached automatically for her vinaigrette.

‘Susan dear, how much you have grown,’ she murmured, weakly.

‘Indeed, Aunt, I am most certainly not a child any more.’ Susan’s words, delivered in her low, and irrepressibly sensuous voice, made her aunt clutch the little silver box more tightly.

‘I leave it up to you, ma’am, to rig my sister out in suitable style. Just let me know the figures involved, and I will let you have a draft upon my bank.’ Lord Tyneham ignored his sister’s implication.

‘Yes, er, of course, Tyneham. Are you staying up in Town?’

Sophy entered, trying her best to look pleased at Susan’s arrival, and made her curtsey to her older cousin.

‘I shall remain in London some time, yes.’ He addressed Lady Chelmarsh, but his eyes were on Sophy. ‘Your servant, cousin.’

‘I hope you are in good health, Augustus.’

‘Thank you, yes. I had a bad chill at New Year, but thankfully it did not settle upon the lungs. Doctor Chislet advocated plenty of goose grease for the chest and I have to say it worked, though I was initially sceptical. One cannot be too careful with chills.’

He answered her prosaically, and she controlled the urge to smile. She had merely asked out of politeness, not expecting details of his most recent ailment. Susan looked at her brother with ill-concealed disdain.

‘Being ill is just boring. Most of the time one may avoid illness simply by refusing to admit its existence. I do not count wounds, of course. They are romantic.’

‘Foolish girl. Romantic indeed, what idiocy.’ Tyneham snorted. ‘You have never seen a wound.’

‘If I did, I would not swoon. You went as white as paper merely over a nosebleed.’

‘I was very fortunate not to break my nose, and Doctor Chislet said that it is possible to exsanguinate through a nosebleed.’

‘Pah! He says anything to please you because he enjoys the way you call for him at the first hint of a sore throat.’

Sophy was at a loss. This was clearly a spat between siblings, but that it should be conducted in front of their aunt, whom they did not even know very well, struck her as unpleasant, and Susan was clearly the one goading.

‘Some people are very susceptible to a putrid sore throat. My own Aunt Dorothea died of one.’ Lady Chelmarsh tried to pour oil upon the waters.

‘I thought that was the diphtheria,’ remarked Sophy, without thinking, and received a look of reproach.

‘How much more putrid could a throat get?’ countered Lady Chelmarsh.

This was unanswerable. It did, however, cause a break in the hostilities between brother and sister, and Sophy, keen to make amends for her unhelpful comment, drew the conversation into something less contentious.

‘It is fortuitous, Susan, that you arrive the day before we have an appointment with Mme Clément for Harriet’s new gowns. I am sure you will come away with your head full of the most ravishing designs.’

‘Oh yes. The trouble is that all the nicest dresses are for those who are married, or at least not in their debut season. All those gowns recommended for their “simplicity and charm” tend to be so very dull and lacking in dash. Who would wish to wear white and pearl pink when there is bronze green and magenta. It is not so bad for you, cousin, since you count as quite old enough to be among the matrons.’

Whether this was merely a thoughtless remark, or one designed as barbed, Sophy still coloured. Susan seemed to comprehend that she had caused offence and made an attempt to negotiate her way out of the awkward situation. All she did was dig a deeper hole.

‘I am sorry, that did not sound kind. It is only that you have been out for so long …’

‘You would look very nice in white, Susan, with your lovely dark hair.’ Lady Chelmarsh declared quickly, and rather loudly. She was getting desperate.

‘Do you think so, Aunt? I wondered if it might not make me look sallow.’ Susan, diverted onto her favourite topic, herself, immediately forgot Sophy.

Her cousin was able to regain her composure, therefore, until she realised that she was being regarded most earnestly by Lord Tyneham.

‘I apologise, unreservedly, for my sister’s outrageous remark,’ he murmured. ‘That she should dare to say … unforgivable.’ He was looking up at her, and his expression reminded her quite forcibly of the estate gamekeeper’s loyal spaniel. ‘She cannot appreciate that not all men look for silly girls as their helpmeet through life.’

She was unsure how to reply. In fact, she would prefer not to reply at all. Her mother noted the spaniel look. Lady Chelmarsh did not think much of Tyneham as a man, but he had wealth, and at Sophronia’s age, perhaps he might prove the only chance she would get. It would be well to watch, and if necessary, cultivate him. The biggest problem looked like being that he and his sister would be at odds within minutes if in the same room.

Sophy was saved by the arrival of Harriet, who was patently eager to show her cousin her room and discuss the current plans for their being launched into society. Lady Chelmarsh would normally have repressed such an unladylike display of enthusiasm, but in the current circumstances was simply glad to get Susan to remove from the drawing room.

‘And I too, Mama, have tasks to which I ought to give my attention,’ declared Sophy, keen to make her escape.

‘Yes, indeed, my dear. I am sure Tyneham understands.’ Lady Chelmarsh saw the look of entreaty in her daughter’s face, but was not going to keep her nephew at arm’s length. As Sophy made her apologies to her cousin and withdrew, she was heard to invite him to dine with them on the morrow, for they had no engagement this early in the Season. Sophy sighed.

Madame Clément was perfectly happy to extend the appointment of the Hadlow ladies to include the beautiful Miss Tyneham, especially when it was made clear that expense was not an issue. Harriet was delighted simply to be the centre of attention and have gowns designed specifically for her, having, in the schoolroom, been quite used to wearing those adapted from clothes her older sisters had outgrown. Lady Chelmarsh had seen no reason why this piece of domestic economy should not be employed whilst Harriet was learning French grammar and dabbling with watercolours. Now she was to be launched into the Ton it was a different matter, a matter of pride, even, that Lady Harriet Hadlow should not be dismissed as ‘just another chit’ on the marriage market. If Sophronia had been a disaster, Frances had been a success, and Lady Chelmarsh was determined to build upon that. Presenting her youngest daughter in flattering but modest apparel, making her, and not her gowns, the focus of attention, was her prime concern, and Mme Clément fully comprehended her customer’s requirements.

Fortunately for the dressmaker, Harriet lacked her sisters’ inches but had a pleasing figure, and suited dresses in a variety of styles, though she admitted the Russian bodice was not as flattering,

While Harriet was the centre of attention, Susan, naturally, became bored, and took to inspecting some of the ensembles upon display. It was a natural progression to calling a minion and demanding to be permitted to try on a very dashing spencer in red velvet and decorated in the military style with gold braid and buttons. The minion was caught between knowing it was not designed for so youthful a lady, and the mulish look on Miss Tyneham’s face, which indicated she would make a nasty scene if refused.

Thus it was that Lady Chelmarsh’s discussion about the suitability of a spangled half dress was interrupted by Miss Tyneham parading up and down in the spencer and announcing that it would be just the thing to wear to the military review in Hyde Park that her aunt had mentioned as one of the treats of the next two months.

‘Er, yes, my dear, but it is hardly …’

Susan’s body language and expression made Lady Chelmarsh wish she had brought her smelling salts.

‘With a very boringly simple white walking dress beneath, ma’am, it would not look too dashing, and the colour suits me so very well.’

It had to be admitted that it did. Mme Clément, seeing both the chance of pleasing her client and making a sale, proffered her professional advice.

‘Mademoiselle does indeed suit the colour, but worn with anything but a gown, ah, of the simplest but most carefully fitted, and in white, would make Mademoiselle look a little … old.’

This made Susan glance in the long mirror. The concept of looking ‘old’ was one she had not considered. ‘Sophisticated’ was a look to which she aspired, ‘old’ was not.

‘Do you truly think so?’

‘Why yes, Mademoiselle.’ Madame managed to sound surprised. ‘When one has the advantages of youth and beauty also, what need has one to make others look at the gown and not oneself?’ She gave a quick sidelong glance at Lady Chelmarsh, who was nodding approvingly, and saw her path clear. ‘You will not mind me saying this, Mademoiselle. Some young ladies must disguise their imperfections with detail. You have no such problem. Advertise your perfections with gowns of good cut but simple fabrics, and let lesser demoiselles hide their faults.’

This made perfect sense to Susan, and, after all, the dressmaker must see very many young clients. What in her aunt she would have dismissed, she lapped up from Mme Clément, not realising that an exquisitely cut gown on simple lines might cost as much as one more opulent in trimming. She was in London to be admired, and break hearts. She would do so better this way.

‘Why yes, that is very true.’

Lady Chelmarsh could have embraced the proprietress, but contented herself with announcing that Madame would create her niece’s wardrobe for the Season, and that Susan might have the spencer, as a gift from her aunt.

Sophy, watching this scene unfold before her, smiled at the adroitness of Madame Clément, and caught the lady’s eye. Everyone had quite successfully forgotten Sophy, which troubled her not at all.

‘But miladi, are you not looking for a gown to make an impression upon the beaux this Season?’

‘Me? Oh no. I have sufficient to—’

‘Actually, my love, I do think you ought to refresh your wardrobe.’ Lady Chelmarsh was in such a good humour at getting past the hurdle of purchasing appropriate toilettes for her niece that a little added expense upon her eldest daughter seemed reasonable, and if Tyneham was interested in her, it might even be considered an investment. ‘Perhaps a new pelisse for when you promenade with your sister and cousin, and a ball dress or two.’

Sophy, knowing that Madame Clément was not cheap, would have demurred, but her mama seemed so keen she simply let the pair of them have their way, and had to admit that having new clothes was rather nice. She consoled herself with the thought that her father would not object to a moderate amount spent upon her to cover the Season.

Other than the fact that Susan chattered all the way back to Hill Street about how many other debutantes would be cast into the shade by her appearance on the social scene, and made Harriet convinced that she would be one of them, the expedition could be termed a great success.

‘For I do not disguise from you, Sophronia, that I positively quaked at the thought of trying to get Susan not to behave petulantly if I did not permit her to select gowns entirely inappropriate to her years. I almost felt that I had to purchase some extra gowns for you in gratitude to Madame Clément, for the way she handled the girl.’

‘So glad I was able to be useful,’ murmured Sophy.

‘And you saw that she was perfectly meek about the choices we made for her.’ Her mother ignored the comment.

What Sophy had seen was adroit handling by an experienced saleswoman, but she refrained from comment.

Lord Tyneham presented himself punctually for dinner, and was delighted to have been placed between his aunt and Sophy at the table. He set about impressing her with his knowledge on a variety of subjects. He sounded, she thought, like an encyclopaedia. He then surprised her by actually asking her opinion.

‘Do you think that young ladies ought to be taught Italian as a language? I can see that being taught to sing in it is useful, but if one went to Italy, it would only be seemly for the husband to engage in conversation with the locals.’

‘I think that …’

What she thought was, it then appeared, unimportant, because he launched into a reminiscence of his sole trip abroad, which had been to Holland because he had an interest in Delft pottery.

‘Oh no, not your boring vases and jugs again.’ Susan sounded disgusted. ‘They are all just blue and white.’

‘Their very uniformity of colour is one of the attractions,’ declared her brother, repressively. ‘It gives the displays order, and one may appreciate the forms.’

‘They are just pots. Blue and white pots. Even Uncle Chelmarsh’s interest in cows is more interesting. They do move, and they are not all the same colour.’

‘I do not think Papa would like blue and white cows,’ whispered Harriet, to her sister.

‘I have a very fine cow creamer in blue and white.’ Lord Tyneham had clearly overheard, and his mind inclined to make very literal connections. ‘There are some collectors who prefer the tulip—’

‘Are we going to purchase hats tomorrow, ma’am?’ Susan cut across her brother.

‘I …’ Lady Chelmarsh was so surprised at the interjection that she blinked, and answered rather than admonish her niece for her rudeness. ‘I thought that we would do so, yes.’

‘Oh good. Just remind me not to look at any with blue ribands. I have quite gone off the colour, and dislike it with white. So very obvious a contrast, and I would hate to look the least like a cow creamer.’ Susan gave a deceptively innocent smile, but threw her brother a swift, challenging look.

He coloured, but refrained from taking the bait, which she merely saw as a sign of cowardice, and stuck her nose in the air, convinced of her victory.

Harriet, whose relations with her brother, her nearest in age, were good, frowned. As brother and sister, it was natural to banter in private, but they would never do so before company, even in jest, and this was not in jest at all. Susan seemed to want to needle her brother at every opportunity. Harriet secretly admired her cousin’s boldness, or at least the self-confidence it showed, but this shocked her.

Sophy, seeing the look on her sister’s face, was pleased. It would be far better if Harriet took no cues from their ill-disciplined cousin. She also rewarded Tyneham for his reticence, by enquiring about the porcelain from the Orient which had inspired the European potters, knowing full well it would enable him to lecture her at length. After five minutes, she regretted this generous act. Her parent, meanwhile, was occupying Susan with a description of the fashions when she had made her own come-out, a generation previously. This was sufficiently entertaining for that young lady to forget brother baiting, and to ask youthful questions and relax in a way which Lady Chelmarsh chose to see as a sign that having her under her roof might not be as bad as she had anticipated. She remarked as such as she stood outside her bedroom door upon retiring, and was wishing Sophy goodnight.

‘Perhaps,’ suggested Lady Chelmarsh, hopefully, ‘Susan has outgrown her childish volatility.’

‘On the evidence of what we witnessed yesterday and today, Mama, I fear that is wishful thinking.’

CHAPTER THREE

Lady Chelmarsh did not have long to linger in her happy self-deception. She was not a woman much given to nervous spasms, but Susan could have induced them in the hardiest of dames. Her mere presence in the house in Hill Street seemed to set it by the ears and create an atmosphere of tension. Bembridge, the butler, who had been in the family service man and boy for forty years, struggled for four days and then went to his mistress and requested a few minutes of her time upon a serious matter.

‘I am so very sorry to have to bring this to your ladyship’s attention, but the situation is such …’ He coloured, and looked extremely uncomfortable.

Lady Chelmarsh felt her heart sink. Her household was not one where disturbance occurred, but there been one very obvious change in it.

‘My niece?’

‘Yes, my lady, I fear Miss Tyneham has been … unmindful of the distance between those above and below stairs. The staff here, I say without puffing myself up, ma’am, are well trained, discreet, and trustworthy. I would not engage, or rather retain on your ladyship’s behalf, any who were not. However, I feel I ought to ask permission to call a meeting of the staff, the male staff that is, and issue firm directions upon the way in which they react to the young lady. I, er, have reason to believe that several young men were turned off at Tyneham Court following “incidents”, my lady. I would not wish such an unfortunate occurrence here.’

‘I see.’

He hoped, most devoutly, that she did not. He had already had stern words with two of the footmen, whom he had overheard arguing over which of them ‘young miss’ preferred, and had to give his protégé, Norris, whom he was grooming to take the position of butler when he should retire, some fatherly advice and a strictly medicinal glass of Lord Chelmarsh’s second best sherry.

‘I am sure Miss Tyneham means nothing by it, my lady, but … She is a very attractive young lady, and it fair turns the heads of the young men when she … it is very difficult when … she plays her tricks off upon the staff.’

‘Her tricks, Bembridge?’

‘She, well, she … flirts. Your ladyship will understand it makes things very awkward for the footmen, being young and impressionable, when she speaks to them just so, and gives them looks which, from young women of their own station, they would see as indicative of, er, interest.’

‘Oh dear,’ murmured Lady Chelmarsh, starting to pleat a lace-edged handkerchief.

‘It will be all innocence, no doubt, ma’am,’ lied Bembridge, who privately thought Miss Tyneham a risk to the entire male gender, and would rather a tiger had been introduced into the household, ‘but I feel I ought to remind the staff that her behaviour must not be taken at face value.’

‘I see,’ repeated Lady Chelmarsh. ‘Indeed, I fear you are right to speak with the men. I am sorry, Bembridge, that the staff are put in this … difficulty. At least it is only for this one Season.’

Bembridge did not think he could survive a second, but made an appropriate response.

Lady Chelmarsh was still working her handkerchief through her fingers when Sophy came in to ask if there was anything her mama needed at Grafton House, whither Sophy was bound to hunt for lace edging for a petticoat.

‘I need peace and quiet, dear, and you cannot purchase me that.’

‘But surely, Mama, one does not come to London for peace and quiet?’

‘Oh no, I meant to be free of worry about … I have just had a very upsetting interview with Bembridge. Susan has been “playing off her tricks”.’

‘Not on dear old Bembridge, surely?’

‘Not on him, at least he did not say so, but on the other men. It is terribly distressing.’

‘I saw her this morning, looking sideways at the new under-footman. She uses them as practice, I think. I believe she likes to feel the adulation. She is not likely to try and run off with a servant.’

‘Do not even say such a thing. It gives me palpitations.’

‘I am sorry, Mama. I have told Susan her behaviour is wrong, and unfair, but she shrugs and says it means nothing, and men should not be so easily duped.’

‘Where will it end? Oh, Sophronia, how can one find a suitable parti for a girl like Susan?’

‘I hate to say it, Mama, but the best thing for her would be a man for whom she feels a partiality but who does not respond to her “tricks”. Perhaps, you know, she needs to fall for a rake.’

‘No, oh no. She could not. It would be unthinkable. What people would say …’

‘Unpalatable it may be, Mama, but it does not make it less true.’ Sophy paused. ‘Shall I take her with me shopping, and Harriet also?’

‘Yes. No. Yes. Oh, Sophy I wish your father were here.’

‘You do not really, Mama, for he would look miserable, and declare you know best in all such matters anyway.’

With which Sophy left her mother to her musings and went to find her sister and her wayward cousin.

Harriet was in Susan’s room, sat upon the bed and watching her cousin instructing the maid how best to dress her hair, and finding fault with every pin. Sophy arrived just as Susan exclaimed that it would look better if she did it herself. The maid was flustered, and thus even more hesitant.

‘Let me, cousin.’ Sophy stepped forward, dismissed the maid with a smile and thanks, and calmly placed the last few pins with deft fingers. ‘You should not berate the maid simply because you are out of patience, Susan.’

‘I was not. She was slow, and clumsy.’ Susan pouted. ‘I am bored.’

‘Well, you need not be so. I am going to Grafton House for lace, and thought you and Harry might accompany me. You were thinking of some hair ribands only yesterday, Harry, and it is a delightful place to spend one’s pin money.’

Harriet was instantly enthusiastic, and Susan became so when she realised that they were walking the short distance to New Bond Street, which might mean the opportunity to see gentlemen, if not upon the Strut at such an early hour of the day, then about their business.

It was but a few minutes’ walk from the house in Hill Street to the ladylike delights of the linen-drapers at Grafton House. They passed through Berkeley Square, and, after gazing into a few enticing windows in Bruton Street, turned right into the lower end of New Bond Street. Whilst the elegant modistes might be visited by young unmarried ladies only with the support of parental wealth, Grafton House was an emporium within whose portals one might spend one’s shillings upon furbelows, and, if one was reduced to such levels, materials with which to make one’s own gowns, or take to a lesser dressmaker. It was not the most fashionable of shops, but was popular. Sophy, having discovered it during her first Season when she wanted to replace some buttons on a pelisse, knew it to be the perfect source of trimming for the petticoat she had nearly finished at home, and had brought up to Town to occupy any quiet time with restful hemming. She was not a notable needlewoman, and had neither the need nor inclination to make her own dresses, but petticoats were a different matter, and provided employment on rainy afternoons in the country.

There was an added advantage to taking her sister and cousin to Grafton House; it was not a place where Susan might be distracted by gentlemen. In this Sophy was correct, but she forgot that Susan was as likely to flutter her eyelashes at a breathless draper’s assistant as at a duke.

They arrived before the shop was too crowded, and whilst Sophy pondered over the advantages of a narrow ecru lace that was unlikely to tear over the more opulent wider examples, she let the younger ladies, with the protection of the maidservant, wander among the fabrics, braids and ribbons. Having selected and requested the appropriate yardage for her project, Sophy’s eye was caught by some very fine lawn, from which she might make both a tucker and some handkerchiefs to embroider for female relatives, and it was only then that she went to seek out her sister.

Harriet was trying to decide between a broad satin ribbon in cerulean blue, and one in a soft green. Susan was contemplating the purchase of silk stockings, not least because handling one she had successfully caught the eye of a young man whose Adam’s apple was bobbing up and down and pulse was racing as she held the item in her hand and gave him a look that turned his mind, firmly focused upon commerce, to jelly, just as she intended that it would.

‘I am bound to wear holes in the heels when we are at balls and parties every night, for I fully intend to dance every dance, so I think investing in another couple of pairs would be a very good idea, do not you, cousin?’ She smiled up at Sophy.

‘Yes, but that presupposes that your dance card will be full.’

‘Oh, it will be full, I can assure you.’ Susan’s self-confidence was boundless, and Sophy realised that nothing she could say would dent it. Then Susan added the comment that cut. ‘You just watch, and listen to the mamas as they wish their daughters were as fortunate.’

‘Thank you, I might even manage a dance myself, you know.’

‘Oh yes, … of course,’ faltered Susan, under a rather steely stare. ‘I … I shall take two pairs of the stockings, though. Has Harriet decided about her ribands yet?’

Harriet had not, and eventually took a length of both colours. Having paid for their purchases, they were placed in the basket held by the maidservant, but Susan, to Sophy’s surprise, chose to carry the wrapped parcel of stockings herself. Had she known her cousin rather better, she would have been suspicious.

They retraced their steps, lingering over shop windows, and making hypothetical purchases which would, in reality, have been wildly profligate. They were gazing into the window of a jewellers near the corner of Bruton Street, and Harriet was waxing lyrical over a necklet of graduated topaz stones.