Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

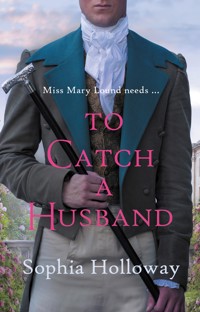

Gloucestershire, 1813. Miss Mary Lound of Tapley End would be the first to say that she demonstrates more grace with a fishing rod in her hand than she might ever twirling in a ballroom. This was not, however, a problem until her ne'er-do-well brother sold the family estate, leaving Mary and her mother in very straitened circumstances. When the new owner, Sir Rowland Kempsey, takes up residence, Mary decides to direct her energies into recovering her beloved home by catching a husband. Promisingly, Sir Rowland thinks Miss Lound is a breath of fresh air. But with awkward attempts at flirtation, a duplicitous predator at large in the neighbourhood and the emergence of feelings that complicate her pragmatic goal, Mary discovers that landing the man she wants is more difficult than she had anticipated. Readers love Sophia Holloway: '5 stars because there are no more' 'A superb regency romance showing a heroine that breaks the mould' 'I love this authors books' 'I've recently discovered Sophia and flew through all of her books ... I'm a long term Georgette Heyer fan and Sophia is definitely as close to matching her magic as is possible'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 464

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

TO CATCH A HUSBAND

SOPHIA HOLLOWAY

4

5For K M L B6

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Miss Mary Lound looked up from her embroidery, which she was working upon with more vehemence than skill, stabbing the fabric in an accusatory manner, and stared out of the window. She was not the sort of young woman who enjoyed needlecraft of any sort, and had it not been for the rain which had come down heavily all day, she would have been out, either upon horseback or her own two feet, for she was a brisk walker. She sighed heavily. It was terrible weather for July.

‘I think that even though the sky is somewhat lighter, my dear, you ought to wait until tomorrow before taking the potted cheese to old Mrs Nacton,’ Lady Damerham suggested, a little nervously. Mary had been very snappish all week, not that her parent blamed her 8for it. For her own part, Lady Damerham regarded what had happened as all just another misfortune laid upon them.

‘You are quite right, Mama, but …’ She shook her head, and was silent for several minutes, before blurting out, ‘I wish I were a man.’

‘Mary! Really, you say the strangest things.’

‘Yes, but if I were a man, I could do something. As it is we are stuck, with no means of earning an income, and on the verge of penury. If I were a man I could join the army, or the navy, or …’

‘You could write a book? Ladies do write novels and—’

‘Me? Goodness, no. I would be pretty appalling at it, and I hardly think lady authors earn more than pin money. Besides, I can think of nothing worse than trying to write one of those fanciful romances with kidnappings and haunted houses and all that foolishness. Having said which, our situation has all the makings of something as silly. “Titled gentleman wastes much of his inheritance gambling, is succeeded by heir who is as thoughtless and has to sell the family estate to meet his debts, and departs for the wilds of North America, leaving his mother and sister nearly destitute.” Yes, that is ridiculous enough to make a novel!’

‘Not destitute, dearest. I have this house for my lifetime, remember,’ corrected her ladyship, gently, ignoring the fact that upon her decease, her daughter would be homeless. 9

‘You have the house, Mama, but how are we to manage? It might have seemed a good idea for you to have a jointure when you married, but it was pathetically small, and how Edmund and his fancy lawyer managed to persuade you to accept a miserable lump sum from the sale of the estate in return for nullifying it I do not know.’ Mary was still fuming over this, for her brother had invited the lawyer to the house when Mary was out for the day visiting a friend, and had not used the family solicitor.

‘But I had to, Mary. The poor boy would otherwise have been severely curtailed in what he could sell, and he said a debtor’s prison threatened. I could not leave him liable to such a fate. He did have it in the estate sale that it was dependent upon me being able to remain in the dower house, do not forget.’

‘I am not sure if he could have tried to sell otherwise, Mama. It is all very murky to me, and that letter from Lord Cradley, upon purchase, was unpleasant in the extreme.’

‘It was not couched in the most genteel of terms, I grant you,’ Lady Damerham admitted.

‘It made it very clear you were to remain only because of the legal requirement, and woe betide you if you as much as stepped upon one yard of “his” land. “His”! The effrontery of it.’

‘Mary, if you maintain this level of ill temper, you will drive yourself to an apoplexy. I am sure of it. There is nothing to be done, except to economise, and though 10we may have to turn off some of the servants, you know dear Atlow would not leave us, even if we paid him not a penny, as long as we gave him bed and board.’

‘Atlow is indeed a dear, but we cannot exist with an ageing butler and a cook-housekeeper, and ultimately only one maid to keep a house this size clean and the fires laid.’

‘It will be … difficult. We must be brave and … Are you absolutely certain you could not write a book, not even a small volume of poems, dearest?’

Mary shook her head and laughed, though it was not a laugh of joyous merriment, and promptly stabbed her finger with her needle.

It was thankfully not long afterwards when the butler announced that Sir Harry Penwood wished to know if the ladies were ‘at home’. Atlow had moved with them from Tapley End to the smaller dower house out of loyalty, but also with relief at the reduced number of stairs, passages and galleries that had to be traversed. He gave the ‘Sir’ an emphasis.

‘Oh, do please show him in, Atlow. How wonderful!’ Lady Damerham pressed her hands together in delight, and when the young man entered the room, came forward instantly and hugged him.

‘Dear Harry. Awful circumstances … so glad you are safe and home … your poor mother, I so feel for her …’

Sir Harry, looking over Lady Damerham’s shoulder 11as she addressed these disjointed remarks to him, gave Mary Lound a wry grin, and then responded, in a serious tone.

‘Thank you, ma’am. I cannot say I had thought to be back in England for some considerable time but … Mama is quite well, and coping, as one does.’

‘She was always so very stoic. I saw her but last week and she made no mention of your return,’ sighed her ladyship.

‘I did not give warning in case I was delayed on the journey and she fretted. You know her one great fear is the sea, and every time I have left England’s shores, she has been convinced I will end up shipwrecked. Anyway, I am back, and to stay, of course.’

‘Of course.’

‘And I must, very belatedly, offer you my own condolences, ma’am, even though you must be nearly out of your blacks by now.’

‘Indeed, another month and … besides, I – we – had time to accept … it was not sudden.’ Her smile returned. ‘We must offer you refreshment. I hope you have not got too wet coming over to see us. Oh, and while I think of it, your mama asked me for the receipt I have for damsons in a batter pudding when we met outside church the other week. A very weak sermon we both thought, which is most unusual for the rector. I had it ready the other day, but where … ah yes! Mary, dear, send for tea, or would you prefer something stronger, Harry?’ Lady Damerham was already halfway to the door. 12

‘Tea would be perfect, thank you, ma’am.’ Sir Harry had almost forgotten how ‘butterfly’ Lady Damerham could be in conversation. He looked again at Mary. She had not changed, he thought, although he had not seen her in nearly three years.

‘Do take a seat “Sir Henry”,’ offered Mary, with a grin and a gesture of her hand, as her parent shut the door behind her, ‘as soon as you have pulled the bell.’

‘If you call me “Sir Henry”, even in jest, Mary, I am not sitting down but walking right out of that door.’

‘I am sorry, Harry. I should not tease you, especially now. It must be both strange and sad for you, coming back when the locality has perhaps come to terms with Sir John’s death, and yet here it is, made new again to you.’ She patted the sofa beside her, and he came to sit down. ‘It was a terrible shock, but at least the suddenness of it meant there was no suffering.’ Her voice softened. ‘He was very well thought of, and nobody doubts the estate is in good hands with you. You are selling out, yes?’

‘Put my papers in as soon as I got back to England.’ He sounded regretful. The army life had suited young Harry Penwood, and he had only had his company for six months. He felt it as work unfinished, especially with Wellington looking set to drive the French out of Spain entirely and back over the Pyrenees, after winning a victory only a few weeks past, and one which had given Captain Penwood his last taste of action.

‘At least you have your ancestral acres, and in a good 13state, too. No fear of poor husbandry there. I …’ She paused as Atlow entered, and requested him to bring tea. When they were once again alone, she pulled a face. ‘You find us suffering from the result of the opposite. However much Papa had to retrench, he never contemplated selling the entire estate, and yet Edmund did not even retain his patrimony for a single whole year, and we are left impoverished, and almost destitute.’

‘But Lady Damerham has the dower house for life, surely?’ Harry frowned.

‘She does, but whether we can afford to live in it is another matter, and my portion is, would you credit it, only to be paid when I marry. So Papa failed to provide for me should I remain single, and thus most in need of financial support.’ Mary did not attempt to conceal her disgust at her sire’s lack of forethought. ‘At this rate I am facing my declining years in some gloomy cottage, with a single servant and mutton once a week, if fortunate.’

‘Put like that, you are in a difficult position, but you will marry, of course you will, and—’

‘I am five and twenty, Harry. I never had a Season to be trotted up and down in London, and I have no regrets about that, but I know everyone hereabouts, and if any gentleman had found me to his taste, or he to mine, I think we would have discovered it by now.’

‘Er …’ Harry looked a little uncomfortable. ‘You do not blame me for not … I mean … we are dashed good friends but …’ 14

‘Oh Harry,’ Mary laughed, and reached out her hand to his. ‘No. We are, as you say, the best of friends, and I daresay there are married couples out there who rub along far worse than we would do, but you and James were brothers to me, whilst Edmund … Do you know, I wondered, when I was a girl, if Edmund was a changeling. I did, really. I had read in some history book that King James the Second was meant to have had a baby boy smuggled into the chamber of his Catholic wife, in a warming pan of all ridiculous things, and a baby girl smuggled out. Well, I suppose that fired my imagination, and I wondered if Papa had smuggled in a changeling that was Edmund. He has always been so unlike James and myself. James would not have …’

Her smile twisted. She missed her brother James, would always miss him. The memorial in the village church was all there was, for he lay in a grave in Portugal, a grave perhaps already overgrown and forgotten. James would not have squandered the little inheritance that remained, would not have sold Tapley End, and never, ever, to the family with whom the Lounds had been at odds since the Civil War.

‘No, he would not.’ Harry understood, and it was one of the things that made him so much like a brother, when Edmund seemed unrelated. Edmund would have looked questioningly at her, frowned in incomprehension. ‘But it is done, Mary. There is nothing you can do about it. Old Cradley has bought the estate fair and square. If I could have afforded it … well, however wrong it 15would have felt to own the place, I would have bought it rather than see it go to him. I could have made over Hassocks Farm to you, or sold it to you for a pittance, and the rent would have kept you in the dower house, at the very least.’

‘It would still be charity, Harry, though meant, and probably accepted, in friendship. It just feels …’ She shook her head. ‘I know Edmund is not solely to blame. We all know Papa was a gamester, and if he had not been so plagued with the gout of late years, we might have been in the suds even before Edmund inherited.’ She sighed. ‘But you would have thought that he, Edmund, would have made a push to come about, not simply carry on where Papa left off and then shrug and say it was not his fault.’

‘He did not say so?’ Harry looked suitably surprised.

‘Oh yes. He even had the impudence to say it was my fault, because if I had married well, then he could have sponged off my husband.’

Harry’s jaw dropped, and it was some moments before he could respond.

‘Well, if that don’t beat all! In all this sorry mess, Mary, at least he is going off to the other side of the Atlantic Ocean to trap beavers or whatever. He cannot do any more harm from there.’

‘True.’ She paused for a moment. ‘I do not suppose I should tell you, since you will no doubt sit as a magistrate as your father did, but I am a thief.’

‘You?’ 16

‘Yes. When I heard who was buying the house and its contents, please note, I had the writing table from the green saloon brought over here, and the portrait of Grandmama that hung in the morning room. And I also brought Sir Robert and the Lady Elizabeth. I thought if they had to see a Risley living in the house they might haunt it, and I was none too sure Lord Cradley would not have had them burnt, as final proof of victory. I replaced Sir Robert with a still life that had been in the attic for years.’

‘Well, then that is not theft but rescue.’

‘You may shortly be on the bench, Harry, but your grasp of law is …’

‘Tenuous? Not really. But look at it this way. Cradley is not going to use a lady’s writing table, loathed your grandmama, and might indeed have committed your ancestral portraits to the flames. He has not been deprived of anything he would miss, and they are your ancestors.’ He smiled.

‘Bless you,’ Mary smiled at him, but it wavered. ‘I keep thinking this is all just a nightmare, but it is not. I cannot forgive Edmund. He did not even bother to see if anyone else would offer for the estate, and took Lord Cradley’s frankly insulting offer as if it were manna from heaven. I would have been so ashamed if I had brought us to such a pass, that I would rather have drowned myself in the lake.’

‘Has Cradley strutted about the place yet?’

‘I believe he came over once it was all legal and final, 17and sneered at everything before having it shut up. He even turned off most of the servants. That was about ten days ago. I cannot think what he would wish to do with the house, though it is far nicer than his own. For all that I complain of bad husbandry, his land is good, though no doubt he will increase the rents and take what he can from ours. He did send a very formal letter to Mama, expressly forbidding “trespass etc.”, by which he very clearly meant me walking the grounds, let alone fishing. It is not as though he fishes himself, either.’

‘You will miss that. Though it goes without saying that you can come over and try your luck on our beat of the river any time you wish.’

‘I warn you, Harry, if I do, I will be striving to catch our dinner. Just think of the economy if I could avoid us having to buy fish.’

Lady Damerham was quite surprised to re-enter the room to find them laughing, and looked from one to the other. Since she did not like seeing people unhappy she did not complain.

‘Here you are, Harry. It was just where I thought it was … at least the place where I thought it was after it was not where I first thought it was.’ She held out a piece of paper, upon which the recipe was written in her neat, rounded hand.

‘Thank you, ma’am. I will make sure that I hand it over as soon as I get home.’ Harry, who had risen, smiled at her and took it, then looked to Mary again. 18

‘Is it true, what my mama says, that Madeleine Banham is no longer a snub-nosed schoolroom chit who pouts when she is thwarted?’

‘Well, I have not seen her thwarted for some time, so I cannot vouch if she has changed in that respect, but she has undoubtedly unfurled her petals into something of the local beauty. I think her mama is hoping to bring her out informally in Bath early next spring, and then they are taking a house in London, but I am not sure it is confirmed as yet. She would take, though, not a doubt of it. You had best join the queue, Harry, if you want to sigh over her.’

‘Me? Not the sighing type, as you well know. Good to be warned, though, because I would look a perfect blockhead if I asked “Who is that?” and it was Maddy Banham. I take it her mama is just as French as ever?’

‘Absolument.’ Mary grinned and wafted her hands about in a theatrical manner.

‘Lady Roxton is a very charming woman,’ said Lady Damerham, trying not to smile.

‘She is, Mama, but after nearly a quarter of a century in England she still sounds as though she landed in Bristol last month. Do you remember, Harry, how we used to try and drive the conversation so she would say “Wales”, and it came out as “Wayoools”?’

‘I do.’

‘Very naughty the pair of you were, I have to say. Poor woman, it was not her fault she came straight from 19the murderous situation in France … how can people be so bloodthirsty? … and with a very weak grasp of our language. She was so beautiful, though, that Lord Roxton, not that he was Lord Roxton then, snapped her up very swiftly, despite his father’s reservations about “Gallic volatility”, and she has been a good wife and mother, whatever anyone says.’ Lady Damerham always liked to be fair, though it left Mary and Harry both wondering who the ‘anyone’ might be.

‘Indeed, Mama, but her accent is such one might use it as a caricature of a Frenchwoman speaking English, even now.’ Mary offered Harry more tea, but he declined.

‘Thank you, but no. I ought to get back before the heavy rain commences again. The clouds were gathering in the west as I arrived. I just wanted to see you both and … well, if battle lines are drawn around here, you always know that I stand in line with you, sword drawn, so to speak, and you can trust me to stand firm in the face of the enemy.’

‘We know, Harry, and it helps. Of course, there has never been a Risley we liked much, but the current holder of the barony happens to be a particularly unpleasant and contrary specimen. It does mean that not only you but most of this part of the shire range against him. If only that helped pay the bills.’

‘We must not be mercenary, my love,’ admonished Lady Damerham.

‘Not mercenary, Mama, practical. I am no 20needlewoman, and if my gowns have to be taken in, I could look a positive fright.’

‘I promise to warn you of that.’ Harry gave her hand a squeeze, bowed more formally over Lady Damerham’s to avoid another hug, and departed.

CHAPTER TWO

Miss Madeleine Banham was torn. Part of her, a very large part, lapped up the adoration of the local bachelors with pleasure, though a rather smaller part resented that most of them would not have cared if she had lacked every one of the accomplishments which she had worked so hard to perfect at the select Queen’s Square seminary where she had spent her later schoolroom years. A pretty face and a good figure were all that they sought, and saw, but Madeleine was proud of her watercolours and her performance upon the pianoforte, to which she still devoted a half hour of practice every morning. When she did receive compliments about her art and music, she knew she would have received exactly the same had her ability been mediocre, because the gentlemen wanted to please 22her. It was slightly lowering. Her mama told her that it did not matter, but that very small voice inside her told her that her beauty and figure would undoubtedly decline, but she might be an even better painter and pianist at the advanced aged of thirty-five or forty.

She was a patently feminine creature, who floated rather than trod, had a laugh that was naturally bright and musical, and a voice that one besotted youth described as ‘an angel with a mouthful of honey’. Since he had been so unwise as to say this before Miss Lound, this had led to her describing the problems an angel would have with diction, and the deleterious effect of sticky fingers upon celestial harps. Whilst Madeleine could see that it was a very silly thing to say, the thought had been sweet, like the honey, and Mary Lound was far too prosaic and practical. There were nearly eight years between the young ladies, and they had thus never been close. For her part, Madeleine thought the other rather an Amazon, and even ‘mannish’, for she had no fear of muddy skirts from traipsing around the countryside on foot, killed fish with her bare hands, and would rather spend an hour loosing arrows into a butt than dancing quadrilles and flirting. In fact, Madeleine was pretty sure that Miss Lound was incapable of flirting. It was no surprise, as her mama said, that she had never had a suitor and looked almost certain to remain a spinster for the rest of her days. Madeleine could ride, of course, but did not hunt, and preferred to hack gently about the 23locality, being social, and wearing a habit that showed her figure to perfection.

This particular morning, her papa had suggested she ride with him ‘to get the roses back in your cheeks’. He awaited her in the hall, unperturbed by the fact that she was keeping him waiting, since she was always a little late for everything. Lord Roxton, a still handsome man in his late forties, enjoyed being congratulated on his daughter’s good looks, even though he always ascribed it to her mother’s beauty. Lady Roxton, having provided her husband with three sons and a daughter, had lost the trimness of figure as well as the bloom of her youth, but was accounted a very fine-looking woman ‘for her age’, which was, of course, damning. Madeleine descended the stairs, a vision in dark green, alleviated by her lace-edged, snow-white cravat and a curling feather in her hat which accentuated the red gold in her artless curls. Father smiled at daughter and nodded approvingly.

‘Very nice, my dear. We must be careful if upon the more frequented roads, or we will have gentlemen driving into the ditches when they gaze upon you and cease to pay attention to their leaders.’

‘Papa, you should not.’ Madeleine blushed.

‘I speak the truth, no more and no less. No wonder young Sopwell dripped his soup down his waistcoat when you smiled at him at dinner the other evening.’

‘Mr Sopwell lacks polish,’ said the girl who had yet to make a formal come out.

‘He is a trifle green, but a good lad, and—’ 24

‘Are you going to ride upon the ’orses, or stand talking all morning, milor’?’ Lady Roxton emerged from a small saloon and shook her head at her husband.

‘We shall be off directly, my love.’ His lordship was, like many husbands, firm in great matters, but under the uxorial thumb in minor ones.

She came forward with a soft rustle of skirts and brushed a probably non-existent piece of lint from his coat, looking up at him with an affection that Madeleine found slightly embarrassing and that made him feel a decade younger in an instant.

‘Bien. Off with you, and be sure to return before the hour of one.’

He leant and kissed her cheek in a very mild salutation, but Madeleine looked away. Parents really did put one to the blush.

It had been over a week since Madeleine had been out riding, and her mount was a little fresh. She was a competent horsewoman, but her sire nevertheless did not engage her in conversation until she had stopped the animal sidling and brought it down off its toes, and he watched her, fully prepared to grab the bridle above the bit if required. When Copper was at last docile, they left the park and trotted along the Gotherington lane, stopping briefly to exchange civilities with the local doctor, who was looking somewhat weary after attending a difficult birth, and waiting for a flock of sheep to be transferred to pasture upon the other side of the lane. 25

‘I fear we shall not go as far as I would have wished, my dear, if we are to be home in time for luncheon.’ Lord Roxton did not sound too put out. ‘But now the fields are stubbled, we could cut back cross-country, if you are happy to do so.’

Madeleine agreed to this, as long as they used the gates rather than put their horses at them and jumped. They were on the point of turning about when a horseman came around the corner towards them, and pulled up when he recognised Lord Roxton, though his eyes did not linger upon the peer, but rather upon Miss Banham.

Sir Harry Penwood did not sigh; he stared.

‘Good Lord,’ he breathed, reverently. Lord Roxton’s lips twitched.

‘That, Sir Harry, is not exactly complimentary.’ Miss Banham looked coyly at him from under her lashes, and if he had been stunned, for her part she was a little impressed. When she had last seen him, three years past, she had only been on the cusp of finding gentlemen interesting, and Harry Penwood had the disadvantage of being known well since he had been at the playing pranks stage. He had looked nice in his regimentals, she remembered, but was rather dismissive of a young lady still in the schoolroom, and as yet to bloom into womanhood. There was nothing of the youth in the broad-shouldered man before her, except his ill-concealed amazement.

She had certainly bloomed, he thought, as his brain 26regained the ability to function.

‘My … my apologies, Madeleine, or rather, Miss Banham.’ He touched the brim of his hat and nodded also at Lord Roxton. ‘Good to see you again, sir.’ He gulped.

His lordship was quite used to seeing men’s Adam’s apples bob up and down when they first beheld his daughter, and smiled, though it faded with his words.

‘Glad to have you back among us, though I regret the circumstances, of course. Very unexpected. Shock to us all.’ Lord Roxton was not a man of crafted phrases.

‘Yes, sir. I hope Lady Roxton is well. I can see that M … iss Banham is in perfect health.’ Harry glanced at her. He dare not do more because his eyes felt as if they would be on stalks.

‘My wife is very well, thank you. I realise that Lady Penwood will not be socialising, of course, but we would be more than pleased if you come over to the Hall to see us some afternoon, would we not, Madeleine?’

‘Oh yes. But you will not tell us about gory battles, will you? Mr Bromley did so, and Mama and I disliked it excessively.’

‘You can be sure that I will not do so.’ Harry could think of nothing less suitable for a lady’s ears, and was himself more than content to leave the least happy aspects of soldiering in a box of memories to be opened rarely, and in private. There were, of course, the lighter moments, the funny stories, which, in expurgated form, might be brought out in mixed company, but they were 27not about war and death but living in the field, and among friends.

‘It is good to have another younger fellow in the vicinity. Brightens things up. Far prefer having balls to evenings of whist with the aged and decrepit, and you cannot have dancing without gentlemen fit to caper about.’ Lord Roxton liked dancing.

‘I confess, sir, I have not had much occasion for “capering about” these last few years, but I am sure I remember the steps.’ Sir Harry was thinking how good it would be to dance with Miss Banham.

‘I thought Lord Wellington encouraged dancing, when the army is out of the fighting season.’

‘Oh, he does, but that is mostly among the staff, and those quartered close enough. Never found myself in the right place at the right time.’

Miss Banham’s horse began to fidget. Papa had a tendency to take over a conversation and lead into subjects she found very boring, like politics, and the war. Whilst he did not notice her becoming bored, he did notice the horse.

‘Well, we must be on our way. Have to be back by luncheon or her ladyship will give me a rare dressing down, and we have already been held back by a flock of sheep.’ Lord Roxton winked, to remove any idea he was in fact under his wife’s thumb. ‘Do ride over and see us soon, Penwood.’

‘You can be sure that I will, sir.’ Sir Harry touched his hat with his whip, and rode on, in somewhat of 28a daze. When he encountered Mary two days later in Cheltenham, where she had gone with Lady Damerham to purchase gloves, he laughingly chastised her for not giving him a true warning of Madeleine Banham’s transformation.

‘I nearly fell off my horse,’ he admitted. ‘She is so much changed.’

‘Not changed, just grown. Be fair, Harry, she was still stitching samplers when you last saw her.’

‘Very true, but …’ He gave a deep sigh of appreciation.

‘Oh Harry, you said you were not one to sigh over females.’ Mary shook her head at him.

‘Never have until now, but then I have never seen a girl as beautiful as Madeleine Banham.’

Mary laughed, but was conscious of a feeling that was not, could not be, jealousy, for she did not think of Harry Penwood other than as a dear friend, but was yet a form of annoyance at the way Madeleine Banham could put men under her spell with little or no effort, and not just silly young men either.

‘I had thought better of you. Before you swoon at the sight of her, try and discover if you like what lies beneath the beauty.’

‘You sound like my mama.’ Harry grinned.

‘Thank you so much. I now feel positively aged, not just on the shelf.’ There was the slightest hint that the remark had touched her on the raw, and Harry Penwood had known her long enough to note it. 29

‘You, madam, are only “on the shelf” if you choose to be so. You could have had half the shire at your door if you wanted, but you have not wanted. Be honest, Mary, you found “youthful admiration” foolish, and kept saying you had no desire to wed and become a man’s possession, like his gun dog or his collection of porcelain. Now, I quite see how that would be so, but if you treat fellows with disdain, or even contempt, you will not find them on one knee, begging you to accept their suit.’

‘I do not treat you with contempt, or disdain.’ She sounded defensive.

‘No, by Jove you do not, because we have grown up together and you pushed me into the horse pond and I sat you in a cow pat when you were six. I love you dearly, as I would a sister, and it is me being fraternal who tells you truths you would rather not hear.’

‘He is right, my dear.’ Lady Damerham, who had said nothing during the interchange, and was a little daunted by her daughter upon occasion, patted Mary’s arm. ‘I am sure you could find a husband if you tried, even now, though it would be a little difficult with the gentlemen who live closest. If we went to Bath in the spring, perhaps, in modest lodgings, you might …’ She halted as Mary glowered at her. ‘It is that or writing a book.’

‘Writing a book?’ Harry blinked and looked at one and then the other.

Mary’s frown disappeared, and she laughed, which relieved Lady Damerham a great deal. 30

‘Mama is convinced that if I want to earn some money to keep us afloat, I have to write a book, one of those awful romances.’

‘Good grief! You are the last person I could imagine doing that. Mind you, I daresay you could write a nice little book on fishing.’

‘I cannot better Mr Best, alas, nor Mr Ustonson.’

‘But neither are lady anglers.’

‘And I do not want to differentiate between the genders when it comes to fly fishing. It is one thing where a man’s “superior” height and strength are of no importance, and remember what happened when Edmund sneered at my catch and said “Quite good … for a girl”?’

‘You hit him across the face with a two-pound trout. James and I nearly fell in the lake laughing.’ Harry’s grin returned.

‘There should never be the qualification “for a woman” in fishing.’ Mary gave him a tight smile.

‘And well I know it. However, if it sold copies …’

‘I could not do it.’

‘A fish romance, then – two trouts with but one single thought, besotted bream, courting carp, dallying dace?’

‘Now you are being too silly for words,’ Mary giggled, which was not something she did very often.

‘How about “dashing former army officer falls for local beauty”?’ he suggested, not entirely joking.

‘No.’ She looked more serious again. ‘I cannot claim to be close friends with Madeleine Banham, but she is 31not yet officially out, and may not know the “rules”. Just be careful, Harry, that you do not see encouragement in what she thinks is mere friendliness. We females can be heartless pieces, you know.’

‘Thank you for the warning. We shall see what happens, but I am definitely going to make a reconnaissance and visit Lord Roxton in the next few days. I may have been bowled over by her looks, Mary, but I am not such a sapskull as you think.’

‘You could not be,’ she retorted, swiftly.

‘Wretch.’ He shook his head but was smiling.

‘Come over and see us also, dear boy,’ requested Lady Damerham.

‘Yes, do that, Harry, despite my insults.’

‘I will.’ He bowed and went upon his way.

‘There is always Harry, I suppose,’ suggested Lady Damerham, thoughtfully, ‘but I am not at all sure he could see you in the light of a wife.’

‘I am absolutely certain that he could not, Mama. Now, you wanted lilac gloves.’

It was a whole week before Harry Penwood fulfilled his promise and came to take tea with them, and he brought his mother, since he felt she ought not to remain entirely without social contact, even in only the second month of her mourning. She sat with Lady Damerham, who was both sympathetic and disjointedly pragmatic.

‘I think sitting at home, with everything about her reminding her of my father, is inclined to keep her in low 32spirits, though she pretends to being “much improved”. Since we have all known each other for decades it is perfectly acceptable,’ said Harry, quietly, to Mary, his eyes on his mother.

‘And Mama understands her situation, even if she and Papa were not close, as Sir John and your mama were. I think widowhood can be very isolating.’

‘Yes.’

‘So, tell me, are you still under Madeleine Banham’s spell?’ Mary tilted her head to one side and gave him a questioning look. He coloured, which gave her the answer before he said a word.

He had paid his call upon Lord and Lady Roxton and been greeted with open friendliness by both of them. Madeleine had been, if anything, a little more reserved, which he liked, though he might not have been as pleased if he had known why. She was not a girl prone to shyness and was quite well aware of her own powers of attraction, but upon hearing from her husband that Sir Harry Penwood would undoubtedly be calling upon them in the near future, Lady Roxton had drawn Madeleine aside and given her warning.

‘’Arry Penwood is not some green boy who will make the eyes of the sheep at you, and let you treat ’im like a lapdog. ’E has not so very many years, but ’e has been a soldier, and that makes toute la différence. You cannot play the tricks with such a man, so look, and think, before you smile just so and add ’im to your list of conquêtes.’ 33

‘You make him sound quite dangerous, Mama.’ Madeleine laughed, but frowned also.

‘Not dangereux, but not a man with whom you can trifle.’ Lady Roxton paused for a moment. ‘You are very young, ma petite ingénue, but of great beauté, so men will adore you, men of many sorts.’

‘You do not think Sir Harry a bad sort, Mama?’

‘Not at all, but the adorings of boys are not the same as those of men grown.’

This slightly cryptic ‘warning’ left Madeleine unsure how she ought to react to Harry Penwood, and thus it was a rather more serious Miss Banham who handed him his teacup and listened to his description of dolphins swimming beside the ship that brought him home, which he considered suitable for ladies and tea. He found it the more captivating.

‘She is not a featherhead, which is good to know,’ declared Harry, ‘and so many beauties are. I suppose they think all they have to do is smile, and that learning is irrelevant. She asked sensible questions about the dolphins.’

‘The dolphins?’ Lady Damerham was distracted from her conversation with Lady Penwood, and looked very puzzled, having only a rather hazy idea that they were either very big fish or very small whales, and perhaps whales were fish, or ate fish, though she was almost certain fish did not eat whales.

‘Yes, ma’am. I was describing them swimming alongside us as we came up the Channel.’ He did not 34say that Miss Banham had assumed they were fish, since this would be met with derision by Mary, but then Mary knew about fish and sea creatures. A ‘normal’ young lady would have no reason to have learnt about them.

‘So, she has an interest in natural history. I grant that is better than asking “what is a dolphin?”’ Mary sniffed, and her mama studied the contents of her teacup and did not look at her daughter.

‘And she did not flutter her eyelashes at me and look all coy,’ added Harry, ignoring the fact that she had seemed quite flirtatious at their first encounter.

‘I should hope not. Coyness is immodesty dressed up to be the opposite,’ Mary said, forthrightly, ‘and is not the same as being shy, really shy. Amelia Weston is shy, the poor girl. She looks as if she wants the ground to open up and swallow her if one does as much as exchange the time of day with her, and answers in a whisper.’

‘Her mama has made far too much of her freckles, you know,’ commented Lady Penwood, wisely. ‘The poor girl is now exceptionally self-conscious, and everyone knows that those with red hair are likely to show freckles. One cannot help the colour of one’s hair, though I believe some ladies do “help” it keep from grey.

‘Walnuts.’ Lady Damerham nodded wisely.

‘Walnuts, Mama?’ Mary blinked.

‘Yes, you can use them, crushed of course, to dye hair brown. I am not sure whether it is the nuts or the shells, but it is definitely walnuts.’ 35

Harry Penwood smiled, glad that Lady Damerham had successfully drawn the topic of conversation away from Miss Banham, and encouraged her to ‘butterfly’ her way even further from the original topic. Mary threw him a look which intimated that she understood what he was doing but would not stand in his way. After all, she thought afterwards, she did not want to make Harry, her dear friend, reluctant to talk to her. She must, it seemed, curb her tongue when it came to Madeleine Banham.

The following morning, Mary was seated in the small parlour, sighing heavily over irrefutable figures. It was she rather than her mother who cast her eyes over the weekly expenditure. Lady Damerham had always preferred just to hear the rough figures upon quarter days, but Mary had been used to studying the books monthly. Now, however, with economy as their watchword and a dwindling income that could not be augmented, unless Mary should take to the literary life, she was watching the pennies by the week. It did not make pleasant viewing, although she knew they were most certainly not being extravagant. There was a sufficiency at present, but each week saw the gradual diminution of capital. She heard the bell at the front door, and Atlow crossing the hall, followed by an agitated voice. Setting pencil and figures aside, she got up, and went out to see who had been admitted.

‘What is it, Wilmslow?’ Mary looked at the man 36who had been steward of the estate for a quarter of a century, and whose family had served the Lounds for generations.

‘He’s dead, Miss Mary.’

‘“He”?’

‘Lord Cradley, miss. Just had a note come over from Brook House. Dead as a doornail, he is. Opened a letter that was delivered this morning, stood up from his chair in the library, blustering as was his wont, and keeled over dead.’

‘Good grief!’

‘Fair stunned everyone, it has. I thought as you should know right away, miss, and I was wondering if you could advise me.’

‘Upon what, Wilmslow?’

‘Well, his lordship – his late lordship I ought to say – was wanting me to set up an increase in all the rents that come up for the year at Michaelmas, and it has not been a good year, as you know. Should I—’

‘We are well over a month from Michaelmas, Wilmslow, and with luck the heir will not have come, or not have studied the books, before the quarter day. Say nothing, and do nothing, and that is right and fair by those who deserve fairness.’

‘Glad I am to hear you say that, Miss Mary. I was inclined to it, o’course, but since he was the master, and it was his wish …’

‘He is not the master now, and for that the tenants of the Tapley End estate must be thankful, howsoever 37they may be good Christians and pray for his soul in church.’

‘Aye, miss. All we has to do now is wonder about the new lord, and what manner of man he will be.’

‘He is a Risley. That tells us enough, Wilmslow, more than enough.’

CHAPTER THREE

The obsequies for Lord Cradley were suitably well attended by the gentlemen of the local gentry and aristocracy, though, as Harry Penwood revealed, wickedly, to Mary afterwards, most were there just to be absolutely sure the old misery really was dead and buried. There was a notable absence of relatives, with the exception of a thin lady of mature years who was at the house and presided over the meagre provision of cold meats, sniffing loudly throughout. This was peculiarly distracting, and was put down not to excessive grief but a summer cold. Lady Damerham discovered, via the vicar’s wife, that she was a second cousin who had ‘religiously knitted socks’ for him every birthday. This made Mary laugh when she heard it. 39

‘Now that is genuinely funny, Mama. I have this image of her in my head, needles clicking away, and muttering psalms as the sock grew. “He breaketh the bow and knit two together, twice”.’

‘It is not an occasion for levity, my dear, though I perfectly see that once such an idea was in one’s mind it would be hard to shoo away. I wonder if she thought it might remind him of her existence and mean he left her something in his will?’ Lady Damerham frowned.

‘He might have left the socks themselves to her, but I doubt he gave her a charitable thought otherwise.’ Mary sighed. ‘And now we will have the new Lord Cradley, who is a Risley of the cadet line.’

‘Do not forget that he and the deceased were not upon speaking terms. It may mean that he is in fact a … a charming man.’

‘As likely to find a whale in the Upper Pool, Mama,’ retorted Mary, shaking her head. ‘No, all we await is discovering what unpleasant type he may turn out to be, assuming of course that he comes to take up residence. The Risleys have always been grasping sorts, so it would seem probable that he will. What he does with Tapley End is another matter. Loth as I am to say it, he would be better moving into it from Brook House, for at least it has been maintained properly and is not the rambling mess that the Risleys constructed, adding bits every generation as they came into even more money.’

‘Well, I am not sure the Lounds ever came into 40“more money” after the Lady Elizabeth sold all her jewels to pay for the repairs after the Civil War, and Sir James was elevated to a barony by Queen Anne for that diplomatic affair. Your father never did say what it was all about, other than to say his grandfather knew when to keep silent and when to speak. I think the family has been losing money for the last century.’

‘Yes, and too often by foolishness, not misfortune, which could be forgiven, but it does mean that the house makes sense as a building.’

This was true enough. There was a great hall, of moderate proportions and with later Tudor panelling, that formed half the centre of the house and gave onto the early east wing that terminated in a chapel. The first baron had extended to the west in the Queen Anne manner and created both public reception rooms next to the hall and airy, private chambers in the west wing. The house had grown over centuries, but always in the warm, mellow Cotswold stone, and with symmetry and scale. Brook House, by contrast, had been an empty field until the up-and-coming Tudor merchant Risleys had bought the land, and shown off their wealth with an array of decorative brick chimneys and bay windows that was followed over time by a grand dining room resplendent with plaster caryatids and spurious armorials, a grandiose Palladian portico and, in the last forty years, a ‘mediaeval tower’. As Mary’s father had said, most men built follies they could see from the house, not as part of it. In addition, the early 41demise of the late Lord Cradley’s mother had left the house without a châtelaine and someone to oversee its care. It was thus rather tired-looking and unloved.

‘He might feel he ought to remain in Brook House,’ suggested Lady Damerham, thinking again of the new Lord Cradley.

‘Then he is welcome to it as long as he stays there and does no harm to the estate.’ Mary very obviously meant the former Lound estate. ‘Oh … I lose all patience with the whole thing.’

A week passed, and with it July slipped into August, though the weather had been so inclement of late that it felt as if Michaelmas should almost be upon them already. It did nothing for Mary’s gloomy humour. She foresaw an early autumn and long winter, and the winter months were her least favourite. Whilst she would be prepared to brave the elements in all but the worst weather, her mama became very agitated and worried over her contracting some inflammation of the lungs and limited her activities. Added to which she no longer had her two hunters. Last winter she had been in mourning, and now she was without a mount, so there was no hunting to which she could look forward and that made the winter gloom seem even gloomier, and the knowledge that this year they might attend the parties that proliferated about Christmastide did not fill her with eager anticipation. Meeting friends was all very well, and she enjoyed the talk and the food, 42but there was an air of, yes, competition, among the young women, and she was now aware that she was looked upon as ‘poor Miss Lound, who could not find a husband’. Well, Miss Lound was now undoubtedly ‘poor’, in the pecuniary sense, but until now the lack of a husband had concerned her not at all. Miss Lound of Tapley End had not needed a husband, at least not from among the men she knew.

It was mid-morning, and Mary was coming down the main staircase, lost in her less than happy thoughts, when the bell at the front door echoed through the hall, and Atlow, with a measured pace that owed as much to his age as a butler’s calm, went to answer its insistent tinkle. He opened it to reveal Sir Harry Penwood.

‘Hello, Mary.’ Harry Penwood drew off his gloves and handed them and his hat to Atlow with what was very nearly a grin. ‘I bring news.’

‘Good news, I should hope, from your expression.’ Mary smiled back at him, casting her depressing thoughts to the back of her mind.

‘Well, interesting news, even if not “good”. I thought I would come over and tell you and Lady Damerham of it as soon as I knew.’

‘Then best we find Mama and permit you to surprise us. Where is her ladyship, Atlow?’

‘In the small parlour, Miss Mary. Shall I bring coffee there?’

‘Yes, please.’ Mary tucked her arm through Sir Harry’s and looked at him with narrowed eyes. ‘Very 43interesting news if your twinkle is anything to go by, Harry.’

‘Wait and see.’

A few minutes later he was sat in a large wing chair by a good fire, for it was indeed so damp and chilly an August day that it felt autumnal, and with a cup of coffee at his elbow.

‘So?’ Mary folded her hands in her lap, feigning merely genteel interest.

‘Old Cradley did not leave Tapley End to the Risley heir, who is that distant second cousin, or some such with whom he had a major falling out years ago,’ he announced with aplomb. ‘Brook House is entailed, and must go to that chap, like the title, but since he, Cradley, had just bought Tapley End he could do with it as he wished, and he has left it to the grandson of his aunt, his mother’s sister. Not sure what relationship that is called, and it does not actually matter, but at least it does mean that there will not be a Risley striding about the place to mock the ancestors. That must please you, yes?’ He beamed at both ladies.

‘I suppose it must. Yes, actually it does.’ Mary sighed. ‘What a pity he had not died before he bought it.’

‘Really, Mary, that is not very charitable.’ Lady Damerham shook her head.

‘Yes, but he only bought it barely a month before he died, so I am not wishing him a shorter life, not by much.’ 44

Sir Harry laughed and told her she was a hard-hearted piece.

‘We must be charitable,’ said Lady Damerham, with more determination than belief.

‘You can be for the both of us, Mama.’ Mary was unrepentant. ‘Do we know anything about this heir, to Tapley End I mean, not the title? Might he not just sell it on, since he has no connection with it? Or is he local enough to want to enjoy the landholding?’

‘I do not know much at all, other than his name is Kempsey, Sir Rowland Kempsey, and he comes from Cumberland.’

‘Good grief!’ Lady Damerham exclaimed and spilt a drop of coffee into her saucer. ‘Does anyone come from Cumberland?’ Both her daughter and Sir Harry looked at her with puzzled expressions. ‘What I mean is, people “go to” Cumberland, poets and those odd people who want to see more of nature, but does anyone actually live there, other than sheep and farmers?’

‘We may not even find out, if he looks at the deeds, decides it is worth a tidy sum, and promptly sells it,’ cautioned Mary.

‘Now, there you are wrong,’ corrected Harry. ‘You see, the reason I know all this is that my bailiff was passing the time of day over a pint of ale in The Stag’s Head yesterday evening, and your stewa—sorry … Wilmslow, let slip that the new owner is coming to view the property in the next week.’

‘I must ask Wilmslow if he would be so kind as 45to send Joshua Pilton’s lad over to scythe the lawn next week,’ remarked Lady Damerham, diverting the conversation for a moment. There was a short pause, during which Lady Damerham contemplated the length of the grass, Mary tried to sort her thoughts, and Harry Penwood sipped his coffee, whilst watching the emotions that crossed her face. He could read her like a book.

‘We will have to leave cards, of course, to both gentlemen,’ sighed Lady Damerham, returning to the main topic.

‘Remind me when that shall be and I will have the headache,’ murmured Mary, who very rarely suffered from any such indisposition.

‘We must be civil, dearest.’