7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

At first glance, Jamilla and Ameena couldn't be more different. Both are Yorkshire-born teenage girls of South Asian descent; but whereas Jamilla lives with her conservative Muslim family and is quiet, religious and academically bright, the more worldly Ameena masks her insecurity behind a brassy, bawdy persona and lives with her divorced mum. The two strike up an unlikely, fateful friendship. Ameena teases Jamilla about her hijab, nicknaming her 'nunja', but also accompanies her to a study group at the mosque as a lark. In the wake of a deeply bruising rejection by a popular boy at school, Ameena develops a serious interest in religion. She begins to espouse a militant version of Islam, and communicates over the Internet with a recruiter for jihad in Syria, influencing Jamilla in turn. Filled with a new sense of belonging as well as idealised visions of a new spiritual order, the girls flee England for Islamist Syria. Once there, Ameena marries a jihadi she met online. Jamilla, however, resists marriage and becomes a lieutenant to the wife of a powerful commander, whose 'orphanage' turns out jihadi brides and suicide bombers in equal measure. The girls slowly realise that their new reality is a narrow, brutal universe apart from the one they had imagined. Ameena copes by becoming ever more zealous, and increasingly dangerous to Jamilla. Cornered and desperate, Jamilla must figure out how to save herself from her former best friend…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

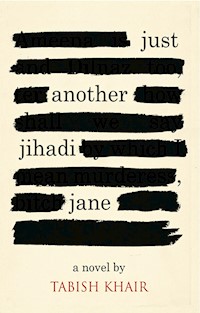

Just Another Jihadi Jane

This edition published in 2016 in Great Britain by

Periscope

An imprint of Garnet Publishing Limited

8 Southern Court, South Street

Reading RG1 4QS

www.periscopebooks.co.uk

www.facebook.com/periscopebooks

www.twitter.com/periscopebooks

www.instagram.com/periscope_books

www.pinterest.com/periscope

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Copyright © Tabish Khair, 2016

The right of Tabish Khair to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

ISBN 9781902932545

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book has been typeset using Periscope UK, a font created specially for this imprint.

Typeset bySamantha Barden

Jacket design by James Nunn: www.jamesnunn.co.uk

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

With my thanks for support and comments to Isabelle Petiot, Claire Chambers (and her family), Gulzar, Neel Mukerjee, Bina Shah, Jim Hicks, Liz Jensen, Sharmilla Beezmohun, Beatrice Hitchman, Seb Doubinsky, Annette Lindegaard, Ellen Dengel-Janic, Conrad Nelson of Northern Lights, Michel Moushabeck, Mitch Albert, Meru Gokhale, Anushree Kaushal, Rachita Raj, Jessica Woollard, Kirsten Syppli Hansen and my agents, Mita Kapur and Matt Bialer.

Dedicated to the memory of Louie Borges Frost (1997–2016), who added joy and laughter to the lives of his parents (my friends Simon and Sussi), his sister Amanda and everyone who came to know him.

These Vs are all the versuses of life

from LEEDS V. DERBY, Black/White

and (as I’ve known to my cost) man v. wife,

Communist v. Fascist, Left v. Right,

class v. class as bitter as before,

the unending violence of US and THEM,

personified in 1984

by Coal Board MacGregor and the N.U.M.,

Hindu/Sikh, soul/body, heart v. mind,

East/West, male/female, and the ground

these fixtures are fought out on’s Man, resigned

to hope from his future what his past never found.

Tony Harrison, V.

1 Reading Scheme

Don’t ask me for too many details. The Devil is in the details, they say. Well, the police are there too, and the anti-terror squad. There is death in the details, and there is guilt, crime and persecution. No, I won’t give you too many details. I shall give you names of places and people, but seldom the exact ones. Like it or not, make what you can of what I say – for you are a writer, and I shall leave this story in your safekeeping. Remember, I am a woman who started off with the conviction that there should be nothing but truth. The One Truth, the Only Truth. I was suckled on that conviction. Ameena wasn’t. I felt I had the truth; Ameena was seeking the truth.

Yes, her name is false, too.

When did I first meet Ameena? I don’t recall. But she told me, in those days in Syria when she could only whisper of the past in a dark room, that it had been on the playground of our school. She had been sheltering behind the slide there, smoking a cigarette. It was a cold, grey day with a hint of rain, a normal day in that part of England. A school with a small playground, strewn with litter around the corner, netted from the streets with high wire, and a grubby, grey building with ugly graffiti at the back – also the sort that is normal in that part of England.

‘You’d come up to me, you know, and told me that Ah shouldn’t smoke,’ Ameena said to me. ‘You were a scarfie, a ninja – no, a nunja. Remember Ah used t’call yer that? All wrapped up, not a strand of hair showing, solemn as always. Ah’d noticed yer before; yer wor t’most solemn girl in t’class. You never joked with t’boys. But wor always fallin’ over to help smaller kids.’

‘What did you do?’ I had asked her, caressing her feverish brow in the dark. We were in a school building then too, in Syria, but it was a very different landscape, a very different education.

‘Ah think Ah told yer to bugger off,’ she said, and the memory, the coarse language, so unusual in that place, all of it made her laugh, which caused her to double over in pain from the lacerations on her body.

I have no memory of this meeting with Ameena. My earliest memory of her is that of a small girl with an advanced camera, a Nikon I think, zoom lens and all. She would go about taking street shots. We had no camera in our flat, but Ameena was a dedicated photographer. We must have been twelve or thirteen then. But I remember that by the time we were fifteen, we were friends. In my recollection, this happened because Ameena and her mum moved into our building, the building where my father had a flat.

Do I need to describe the building? You know the streets where buildings grow straight from the footpath, one after another, their façades bland, with blank windows staring like the eyes of a zombie? You press a buzzer to be allowed in. If the buzzer is working. There are newspapers and wrappers strewn in the foyer and under the staircase. Sometimes the buildings have a lift. Our building had one. It smelled of sweat and deodorant. MAX CAPACITY THREE, a notice said.

You think that sounds bad? It was much worse when I was a child. The lift would smell of vomit and beer then. And there were used condoms and syringes lying about. Then, of course, more of us moved in, and more of them moved out. Some were glad to leave; some gave us the finger. But they left, slowly, one by one, the so-called white working class. Or the white drinking class. The so-called brown working class moved in. It was not the brown drinking class though; it was mostly the Muslim working class. The smell of vomit and beer disappeared. The syringes and condoms disappeared. The graffiti got multilingual. All the rest stayed as it was.

My father had a two-bedroom flat there, with a small study that had been my bedroom for as long as I could recall. When I was ten or eleven, he had a heart attack. My brother Mohammad, who was eighteen then, hustled himself out of school, took a driving test and started running Abba’s cab for the time being. Abba stayed home, reading the Qur’an and becoming even more bitter about the world. He was going to get back to work, but never really did. Mohammad was bringing in more money than Abba ever managed. Occasionally Abba would take one of Mohammad’s shifts, but mostly he stayed home, complaining. Often, he went to the mosque. He had always gone to the mosque on Fridays, Mohammad in tow. He never took me, though some of his friends would let their daughters tag along. But not Abba. ‘It is against our religion,’ he said. ‘Women have to pray separately from men.’

He insisted, however, that Mohammad and I attend classes in conversational Arabic – which, I suppose you know, is almost another language compared to the Arabic of the Qur’an – that the mosque also offered, in a side room. We are Syeds; my father considered Arabic his mother tongue even though he knew only Qur’anic Arabic. I guess no one had spoken Arabic in our family for centuries! But Abba took pride in returning us to conversational Arabic. I took pride in it too, for his sake – much more than Mohammad, who never picked up more than the fundamentals, while I supplemented the side-room classes with correspondence courses. Perhaps I wanted to impress Abba, to be taken to the mosque as Mohammad was, dressed in clean clothes, standing by Abba’s side. It never happened; I learned to go to the mosque’s prayer hall only with other women and girls.

I grew up accepting such judgements from my father, and from other men. Sometimes women too, of course, but my mother never seemed to have a real opinion. She was a timid woman – I assume she is still alive – who had been lovingly browbeaten by her father, and then her husband, and then this incomprehensible new country. In due course, she would be lovingly browbeaten by her son, too. But I am anticipating matters.

Ameena had a very different background. Both of us spoke Urdu at home, but Ameena’s mum was a working woman. Her parents had grown up in Bangalore; they had married in India before moving to England, where her dad was posted by some multinational and where he then switched jobs to settle down – because he liked it so much here, Ameena once said, doing ironic things with her eyes and eyebrows. All this was ancient history; it happened long before we met. I guess Ameena wouldn’t have moved into our neighbourhood had her parents not divorced – and they had divorced years earlier. Ameena told me that she had been seven or eight when they had separated.

Her father was a banker, I think; anyway, something in the financial world, something that fetched good money and required flashy cars and custom-made suits. He walked and talked briskly. To me, he looked like an older version of that Indian tennis player, what’s his name … Leander Paes. I met Ameena’s dad only a few times, when he came to collect or deliver her at our building or in school, and once to help her move. I used to be tenser on such occasions than Ameena. Though he, Ameena’s father, was always charming and gracious. I have to concede that. He had his wife or partner with him on at least two occasions. She stayed in the car, texting on her smartphone. A white woman with limp, thin, blonde hair. I hated her then, because Ameena hated her. ‘This is his number three,’ she hissed to me the first time.

‘He lives with three women?’ I whispered back, shocked.

‘No, this is the third woman he has picked up since leaving my mum,’ she replied. ‘He left my mum for one of them,’ she added. But I didn’t need to be told. I had been raised with the prejudice that good-looking, successful coloured men, unless religious, always left their good, lawful wives for ‘one of them’.

I knew what she meant by ‘one of them’. In those days, she was still smoking on the sly and necking with the boys behind the school building, if she liked the boy or just felt angry at her mum. She particularly liked Alex. Everyone liked Alex. Alex looked like a young David Beckham. He combed his hair like Beckham. He even played football like Beckham. Ameena was in love with Alex. Half the girls in his class, and two classes up and below, were in love with Alex. And Alex, well, Alex was like the mum in that poem by Wendy Cope: he liked them all. Do you know the poem? Reading Scheme. No? I will tell you about it. It has a role to play in my story.

But when Ameena said ‘one of them’, she did not mean all the Pakistani, Polish, Lebanese, Bangladeshi, Welsh, hybrid or whatever girls who had a crush on Alex. She meant blonde white girls who dressed in ways that Ameena’s mum would not permit her to adopt, and who went about with an aura that said, as big as a billboard in neon, I-know-all-about-sex-ping-ping-flashing-lights. Girls who were Lady Gaga on steroids.

Ameena had lovely eyes, liquid and soft, much darker than mine, with the shadow of some unnamed hurt lurking in them. Like a lake at dusk. But you would not call Ameena pretty. You would not call her ugly, either. She was a plain-looking girl with beautiful eyes and thick hair, neither tall, nor short, neither shy, nor vivacious. She had very little chance with someone like Alex, who did feel her up now and then, I guess out of sheer curiosity. He was always far more interested in me. Most men are. Even today, after all that’s happened, I keep this scarf wrapped around my hair because of men’s interest in me. It is not because of faith anymore; I still believe in God, don’t misunderstand me – but I do not think God is a fashion designer. He observes people’s hearts, not their clothes. This is not what Abba believed; this is not what my big brother, Mohammad, believes. This is also not what I believed in those days, when I tried not just to get Ameena to quit smoking but also to start covering herself. But now, well, I still keep the scarf on and wear loose clothes to avoid male glances. And honestly, I do this because it makes me feel comfortable in my skin; anything else would be like wearing a spacesuit, given my upbringing. It doesn’t help too much, though. I get looked up and down in any case. Even you observed me on the sly. No, don’t get flustered. There is probably nothing wrong with noticing a woman. Who knows? I guess it depends on what is in the man’s heart. I did not point this out to accuse you; I just wanted you to know that I know. I know that men notice me.

Alex noticed me, too. Perhaps even more so because I was part of the small group of girls who observed Islamic precepts, or in any case what our parents thought were Islamic precepts. Ameena was not one of us, though in those days I was always trying to spread the word. Mohammad had started bringing in pamphlets from some proselytizing organization that he had joined, and I would read them line by line. Later on, I even joined the women’s branch of his organization, and spent many evenings calling up people – we were given random numbers – and asking them if I could tell them about the Qur’an and our Prophet, pleeease. It was all about spreading the word; da’wah work, we called it. It was the only thing God asked of us: to do our duty, live in the right way, and spread the word, the invitation of Islam. I believed in it.

But I was not naïve. I have never been, in such matters. I knew that Alex had the hots for me. The fact that I was so ‘out of bounds’, as our friend James once put it, must have been a strong aphrodisiac for Alex. That, and the fact that our history teacher, a hairless, slimy old geezer in his fifties, had lisped in class just the previous year: ‘I suppose Jamie here, Jamie would be our idea of Cleopatra, wouldn’t she, if she did not mostly hide herself from view.’ (I hated being called ‘Jamie’ – my name is Jamilla – but evidently Europeans cannot stop themselves from giving new names to people and places. I guess it must be hard to stop after all those centuries of renaming stuff in the colonies.) In that year – we were fifteen or so; Ameena was already living with her mum in our building, so we were commuting together and sometimes hanging out in the school canteen – Alex took to joining us whenever he did not have his short-skirted, fashionable girls around him.

Ameena shone with happiness on these occasions. Alex was always gallant; he flirted with her and paid attention to her. I knew that he was humouring her. In the way he sat himself down at our table, the way he angled his face so that he could stare at me while seeming to speak to Ameena, it was obvious to anyone. But not to Ameena. The girl was gone on Alex: she even referred to him (only when with me, of course) as ‘Mr Ooh-La-La’! It was an expression pronounced with an American lilt that Ameena loved. I was dry and short with Alex, but that did not seem to discourage him. I guess he thought it was just some kind of mating game, a complex one that we – Arabs, Pakis, Iranians, whatever he thought I was – played in our mysterious, intricate lands, but which would finally end in yet another victory for him.

Ameena was still a smoker. But the months we had spent together had made her more careful in her dressing. She was no longer wearing the tight jeans and T-shirts bearing moronic slogans that she had preferred. Now she was wearing baggies and shirts. No scarf yet, though. And of course not the full hijab that I donned outside school; she still teasingly called me a ‘nunja’.

I had started taking her to the discussion group in the mosque, an all-women one that I had been attending for a couple of years now. Her mum – I will call her ‘Auntie’, which is how I addressed her – did not like this. She was a short, birdlike woman of indeterminate age and almost-cropped hair. Mohammad and Abba had commented on that. The hair, that is. Also, on the fact that Auntie wore no hijab, not even a scarf, and on occasion went out in trousers and a shirt. Ammi, my mother, had tut-tut-tutted and then added, ‘But poor woman, she has to work in this country.’ Abba had growled at Ammi: ‘Don’t be foolish. Is that an excuse to give up on your faith? Do Mohammad and I drink because we have to work in this country? These convent-educated Indian Muslims!’ Mohammad had laughed the superior laugh that he employed whenever matters of someone’s deficiency of faith or his superiority in it were highlighted. Ammi took shelter, as she always did, either in the dingy kitchen or in her copy of the Qur’an.

So, no, Ameena’s mum, Auntie, was not happy about Ameena going to my mosque sessions. But she did not object. I think she was relieved to find Ameena doing something that seemed less dangerous than her fears for her daughter. Auntie and Ameena could seldom talk for long without getting into arguments. Ameena blamed her father for leaving her mum, but on the few occasions I saw her with her debonair dad, both seemed happy and the best of friends. When Ameena looked at her dad, you could see the adoration in her eyes. He seemed to have little time for Ameena, and behind his back she would be caustic about him and his ‘number three’. But all of this disappeared the moment he appeared, always looking younger and more dapper than the other dads. You would say that maybe it was only those seconds of meeting and parting that I witnessed. Surely they would have had arguments in between? But I doubt it. I have seen divorced kids with their parents. A meeting starts well and ends badly; a meeting starts badly and ends well. But I never saw any sign of unease, or any kind of upset, between Ameena and her dad when they were together.

With her mum – who toiled hard as a teacher in some school somewhere, and often brought work home – it was different. Ameena was out to irritate her, even run her down. Auntie was not an easy person, or so it appeared to me in those days. She appeared to be opinionated and nagging, and would have been dubbed a ‘tooter’ in school. She was either in a rush or tired, which made her complaining, inattentive or irritable. Her flat was messier than ours, with books, magazines and plates scattered everywhere. I sided with Ameena in all her conflicts with Auntie, even when Ameena was clearly in the wrong. I could see why Ameena’s dad had left her mum. Looking back, I am less sure: I now realize I was unconsciously comparing Ameena’s mum to my own Ammi, a woman who spoke no English, stayed home, got anxious about the smallest of things like shopping on her own, never contradicted either Abba or Mohammad and almost never scolded me for any oversight, real or imagined.

I know Auntie knew about Ameena’s smoking. She must have been told about the pranks that Ameena had been involved in, too. (This was before we became friends.) Ameena would hang out with any boy who gave her some attention, and half the time it would result in some school prank or class warning. The boy – usually a potential drop-out – would do something idiotic, and Ameena would wade into it with wide-open eyes. I do not recall where they had lived earlier on; growing financial pressure after her divorce had made Auntie sell her flat and buy something much smaller. But from the little that Ameena revealed, it was clear that she used to go about with the dregs of her previous neighbourhood. Our school did not have knife-wielding gangs, but there were semi-criminal youth gangs about town – Elm Street Gangsters, Knuckledusters, E7th Rydaz – with whom some boys and girls boasted of hanging out outside school hours. Ameena once suggested she used to know ‘some cool guys’ from a ‘real gang’ in her old neighbourhood. No wonder, then, that despite her dated bob cut, Western trousers and copies of the New Statesman, Auntie did not object when Ameena started fraternizing with me and the local mosque crowd.

At fifteen (or was she sixteen then?), Ameena was no longer a virgin. In that, she was like ‘one of them’. She did not believe that I had never been to bed with a man. Clearly, Alex did not believe it either. Not that it was discussed when he was around; it was just in the air. Alex knew Ameena was available; he knew I wasn’t. But, as I said, he believed I would be. I guess he believed everyone would be available sooner or later. To him, that is.

He had started sitting in our corner during literature class. He would try and position himself in such a manner as to have me between him and Ameena, so that when he turned and said flirtatious things to Ameena, they would need to go through me. The ‘Ice Queen’, he used to call me.

Our literature teacher was an Indian woman called Mrs Chatterjee – we never found out what her first name was – and she loved English and English poetry with the sort of fanaticism that only the ex-colonized bring to both. She tried to inculcate her love for both in us. This was difficult – she spoke English that was correct and chipped but far from what we spoke … far, to be honest, from what I am employing for your benefit. As for poetry – have you ever tried to teach poetry to fifteen-year-olds?

But Mrs Chatterjee struggled. She devised new ways to get us interested in old poets. I did not realize it then, but she was a resourceful educator: she got us to write limericks about our teachers, invited performance poets to read in class, initiated debates and projects on literary issues – including one that I shall have to tell you about later on, for it came back to me during a very different phase of my life. That year, she found another way to get us somewhat interested in poetry: she asked us to bring a poem each, per week, to class. Then we had to sit in groups of three or four, exchange the poems and tell each other why we had chosen that particular poem. This worked, at least to the extent that the boys could bring funny limericks and hip-hop lyrics and the girls could download Beyoncé and mushy romantic poems from the Internet. Alex would come up with better poems. He was not an unintelligent boy. His poems would be what you, as a writer yourself, might call poems, I guess. You know, stuff with some awareness of metre and rhyme; stuff that broke with poetic convention not out of sheer ignorance, but from necessity. I am quoting Mrs Chatterjee. And that is how Wendy Cope’s Reading Scheme entered my life. Because you see, every poem that Alex brought had to do with sex; not in any obvious way, else Mrs Chatterjee would have censored it, but clearly enough for him to gaze into my eyes in a significant manner while reciting the lines out to Ameena or whoever else would be in our group. And given Ameena’s fascination with him, it was impossible for me to manoeuvre her into some other group.

Do you recall Reading Scheme? It is a funny poem. But then, it would be; it’s by Wendy Cope. I remember Mrs Chatterjee was particularly glad about this selection by Alex. She would hop around – she was a short, rotund woman with a pink face and marble eyes – from group to group, inspecting, encouraging, commenting. I used to find her ludicrous. I don’t know why, now. I mean, she was fanatical about her poetry, but then I was fanatical about my religion, as were my Abba and Mohammad and all my mosque friends. She was an extreme admirer of her Romantic notion of poetry, in the same way that Wahhabis are extremist admirers of their notion of Islam. How could I see the fanaticism in her absolute love for Wordsworth, Byron and Shelley and find it ludicrous, but take my own fanaticism so seriously, so unconditionally?

Anyway, Mrs Chatterjee was delighted with Reading Scheme; she usually tried hard to hide her lack of enthusiasm for any verse by a poet who had not been dead and buried for about a century. She asked Alex to read it out loud. Alex obliged, reciting in his deep voice, looking me in the eye when the suggestive lines came up: ‘Come, milkman, come!’ Quick stare. ‘The milkman likes Mummy. She likes them all.’ Stare with a smile. ‘Here are the curtains. They shut out the sun.’ Stare with raised eyebrow. ‘Look at the dog! See him run!’ Stare with a slight leer, the stress on ‘dog’.

See, I still remember the lines.

Neither Mrs Chatterjee nor Ameena were noticing the target of Alex’s stares. Mrs Chatterjee was fixated on the poem, and Ameena on the reciter. Maybe it was this, or maybe it was Alex’s impudence: in any case, I reacted strongly. It is a dexterous poem, using a reading scheme to talk humorously about a suburban mum having an affair with the milkman and being discovered by the husband, all of it narrated through the perspective of her two small children. We had previously read much more adult stuff in literature and history. Usually, I would ignore such texts even though I felt offended by them. But that day, I could not. So, when Mrs Chatterjee asked us, as was her custom, to say what we thought of the poem, I blurted out, surprising myself: ‘Poofy words!’

Mrs Chatterjee did not understand my criticism. Maybe she didn’t even fully understand ‘poofy’; she had grown up in India, and spoke a clipped, literary English like they do on the BBC. She started talking about the deftness of the poem, and how it is a villanelle, which critics say cannot be used to narrate a story – remember Dylan Thomas’s Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night, with its beautiful repetitions, its lack of linear progress in terms of action or story? – but look, Wendy Cope has, with such cleverness, such dexterity, ah, used the villanelle form to tell us a story, shall we say, an action story that moves from one point to another in a linear fashion, and makes us laugh at the same time.

Alex tried to look into my eyes with his knowing smile. It provoked me further. ‘Maybe ’tis funny to you,’ I said, breaking into dialect despite my rigorous attempts to speak ‘proper’ English (unlike Ameena, especially in those days), ‘Ah’ll say ’tis an obscene poem, ’tis ’bout a sin me God forbids. ’Bout ’dultery. Raight? That’s nowt to use for cheap laughter.’ Mrs Chatterjee was a bit taken aback by that, but she insisted that it was not an obscene poem; after all, it does not celebrate adultery, does it? The milkman is chased from the bedroom by the gun-toting dad. Couldn’t I see the humour, the irony … ?

The irony? I argued back, righteously. Alex looked on with the same smile. Finally, Mrs Chatterjee said, ‘Jamilla, why don’t you take this poem home and look at it again? Write two hundred and fifty words on it, and we will discuss it in class next week. Write whatever you feel about it, but write it down. That is all I want you to do. Think over the poem again and write down what you feel about it.’

‘But Ah’ve told yer: Ah think nowt of it,’ I retorted, sticking to the dialect in defiance of Mrs Chatterjee, although she had never tried to get even Ameena to talk ‘properly’.

‘That is fine. But just write it down in that case. I will accept whatever you say, as long as you look at the poem again and write down your own views.’

Was she trying to get out of the debate, or did she hope that writing down my views would somehow make me relent or take a more nuanced view of the poem? It didn’t.

I must have spent more time on that two-hundred-and- fifty-word essay than I ever did on any other homework. I was angrier than I had ever been. And, strangely, even then I felt that my anger was in excess of the occasion: I could see that it was a comic poem about a stereotypical escapade. I could admire – for I did remember the Thomas villanelle – the technical dexterity of Cope. I could even feel a smile, the ghost of a smile, forming at some of the lines, especially the refrain of ‘Look at the dog! See him run’, which starts off as a description of the family dog and ends up as a description of the milkman being chased away by the husband. But partly because of that ghostly smile, partly because of Alex’s smug confidence and, finally, because of Ameena, who claimed to know all about these matters, having ‘done it’ with at least two boys, because of all these factors and maybe others, the more I felt that my anger was excessive, the angrier I got. If I thought, as I did then, that Cope’s poem was a dirty little ditch, then what I poured into it was an ocean of pure vehemence, anger that seemed to come from beyond me and left me feeling angrier.