Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

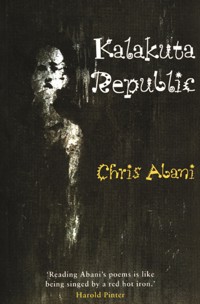

This powerful collection of poems details the harrowing experiences endured by Abani and other political prisoners at the hands of Nigeria's military regime in the late 1980s.Abani vividly describes the characters that peopled this dark world, from prison inmates such as John James, tortured to death at the age of fourteen, to the general overseers. First published after his release from jail in 1991, Kalakuta Republic remains a paean to those who suffered and to the indomitable human spirit.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 55

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Chris Abani

SAQI

For

John James, cellmate, friend, brother,

tortured to death, June 1991, aged 14

and

Obioma Nzerem, Valentine Alily, Jacob Ross,

kindred spirits, dreamers, fools.

Acknowledgements

There is no way I can thank those who gave their lives so that I could live to tell this story. But there are people I can thank. Kwame Dawes and Bernardine Evaristo for their generosity, and critical and editorial feedback. Jacob Ross for initiating me into the final levels of my craft. Adrian Dutton for the amazing paintings that began it all and for the opportunity to be part of Still Dancing. My family for supporting me always – my mother Daphne and siblings Mark, Charles, Gregory and Stella. My father Michael, whose inability to understand me has led me to seek deeper and better ways of saying things. Pamela Osuji for always being there. Jillian Tipene for her help in developing my reading and performance skills and for that special friendship. Victor Okigbo for my first lessons in the art of poetry in 1987. Adam Pretty whose craft and patience in teaching me the saxophone has changed the rhythms of my writing. Delphine George who has made me a believer again. Helena Igwebuike and all my friends. John Moser and David Rose – men of honour. Juris Iven and deus ex machina in Brussels, without whom I might be dead. Patrick Galvin, Pat Boran and everyone in The Republic of Ireland – especially the Dublin posse. Harold Pinter, Moris Farhi, everyone at Saqi Books for believing, and everyone who has helped and supported me in the development of this work and my art in general – you all know who you are – thank you.

Contents

Author’s Note

Introduction, by Kwame Dawes

Portal

Portal

Mask

Old Warrior

Rasa

Oyinbo Pepper

Chain Reaction

Ahimsa

Passion Fruit

Concrete Memories

Tequila Sunrise

Roll Call

Job

Killing Time

Jeremiah

The Box

Eden

Paper Doll

Tattoo

An English Gentleman

Waiting for Godot

Casual Banter

Boddhisatva

Koro

Mephistopheles

Good Friday

Ode to Joy

Caliban

The Hanged Man

Buffalo Soldier

Heavensgate

Mango Chutney

Rambo 3

Passover

Still Dancing

Birds of Paradise

Square Dancing

Stir-Fried Visions

Egwu Onwa

Terminus

Smoke Screen

Reflexology

Solitaire

Mantra

Dream Stealers

Nirvana

Moby Dick

Six Ways to Deal with It

Articles of Faith

Epiphany

Jacob’s Ladder

Postscripts – London

Postcard Pictures

Things to Do in London When You are Dead

Field Song

Haunting

Easter Sunday

Returning From Croydon

Babylon

Changing Times

Days of Thunder

Not a Love Song

A Definition of Tomorrow

Author’s Note

This collection of poetry is based around my experience as a political prisoner in Nigeria between 1985 and 1991. My first experience of this was the result of the publication of my first novel when I was sixteen. Two years after publication, in 1985, I was arrested as my novel was considered to be the blueprint for the foiled coup of General Vatsa. I was detained initially for six months, in two-three-month stretches. Released, I hid the details of my arrest from my family. This initial brush with the government was not deliberate on my part, but having once been brushed by the wings of the demon, I became a demon hunter. In 1987, when I entered university, I joined a guerrilla theatre group which performed plays in front of public buildings and government offices. The government wasted no time in re-arresting me. This time I was held for a year in Kiri Kiri maximum security prison.

In that year, I came to question everything I had believed in before. The only thing I never gave up on was the conviction that there can be no concession in the face of tyranny and oppression. I also learnt how truly ephemeral our mortality is. Released with no explanation, I returned to university and between studying for my degree in literature and developing my love of jazz, I wrote a play for the 1990 convocation ceremony for the university. The play, Song of a Broken Flute, led to my third and final period of incarceration for eighteen months, six of which were spent in solitary confinement. I was sentenced to death for treason – without trial – and held on death row with murderers, rapists and other convicted criminals.

In the last eighteen months, I shared a cell with a fourteen year old boy, John James, and twenty other men. John James did not leave Kiri Kiri alive. And there were many others. I have tried to represent those men and boys that I met, including the guards, as best as I can, without idealising anyone. The most difficult thing about my whole experience was not being able to share my pain, having to hide it from my family for their own protection and from my selfish need not to be talked out of doing the things I felt I had to.

And now? Every day is a careful balance fought between the despondency that threatens to swamp me and the incredible joy of living. I think that my art, my poetry, prose and music come from these cracks in my being, these ley lines where spirit is said to reside. I have come out of the horror of that experience having lost my faith in the inherent goodness of humanity, yet curiously appreciating even more the effort it takes to be good. I also kicked a bad smoking habit! If in reading these poems you can see the courage of the men and boys I write about, if you can feel their essential humanity, and realise that the best things in us cannot die, then I will have succeeded.

But remember always, that freedom, love, kindness, honour, justice and truth are never to be taken for granted – but worked at, struggled with and fought for, at whatever cost. For it is this that makes us human and builds a bridge to our true nature, which is spirit.

Baraka Bashad

Chris Abani

London, June 1997